Bach: A Passionate Life

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Bach: A Passionate Life. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Johann Sebastian Bach is the ultimate composer's composer, | 0:00:05 | 0:00:09 | |

influencing countless others who followed him, from Mozart | 0:00:09 | 0:00:13 | |

to Mendelssohn, Beethoven to Brahms, | 0:00:13 | 0:00:15 | |

and not just in classical music. | 0:00:15 | 0:00:18 | |

From Duke Ellington, to the Beatles. | 0:00:18 | 0:00:20 | |

Musicians in jazz and pop have also fallen under his spell | 0:00:20 | 0:00:23 | |

and learnt from his techniques. | 0:00:23 | 0:00:26 | |

Bach is still the benchmark, a musical gold standard. | 0:00:26 | 0:00:33 | |

We know very little about Bach's life. | 0:00:33 | 0:00:35 | |

There are only a few facts to go on, and our image of him | 0:00:35 | 0:00:38 | |

is skewed by statues and paintings of a stern, | 0:00:38 | 0:00:42 | |

forbidding figure in a frock coat and a powdered wig. | 0:00:42 | 0:00:45 | |

But then there's the music. | 0:00:45 | 0:00:47 | |

# Herr | 0:00:47 | 0:00:49 | |

# Herr | 0:00:49 | 0:00:51 | |

# Herr... # | 0:00:51 | 0:00:53 | |

The music tells us something completely different about him. | 0:00:53 | 0:00:55 | |

It's full of energy, full of dance, full of life. | 0:00:55 | 0:00:59 | |

Over a lifetime of getting to know, singing and conducting Bach's music, | 0:00:59 | 0:01:04 | |

I've formed a series of hunches about his personality and character. | 0:01:04 | 0:01:09 | |

In this film, I want to test them out with fellow Bach enthusiasts | 0:01:09 | 0:01:12 | |

and scholars, and performs some of his most important works, to see | 0:01:12 | 0:01:16 | |

what they can tell us about the extraordinary man who composed them. | 0:01:16 | 0:01:21 | |

He really throws everything at it. | 0:01:21 | 0:01:24 | |

You know, it's just such an overwhelming exploration | 0:01:24 | 0:01:26 | |

of what is to be a human being. | 0:01:26 | 0:01:30 | |

I think he's a scientist at work, and instead of using | 0:01:30 | 0:01:33 | |

the language of mathematics, he's a scientist using music. | 0:01:33 | 0:01:39 | |

The level of inspiration on which he works is, I think, | 0:01:39 | 0:01:41 | |

unparalleled in the rest of music. | 0:01:41 | 0:01:45 | |

Such splendour and wonderfulness, that, on its own, | 0:01:50 | 0:01:53 | |

would convince me that there was a God | 0:01:53 | 0:01:55 | |

if I felt inclined to take that conclusion from it. | 0:01:55 | 0:01:58 | |

In this film, I want to build a new statue of Bach, to see | 0:01:58 | 0:02:03 | |

if we can detect a beating heart | 0:02:03 | 0:02:05 | |

and a more approachable personality underneath the wig. | 0:02:05 | 0:02:09 | |

My own engagement with Bach began as a small child | 0:02:21 | 0:02:24 | |

growing up on a farm in Dorset. | 0:02:24 | 0:02:26 | |

Just before the war, | 0:02:26 | 0:02:27 | |

a refugee from Nazi Germany arrived with a painting in his rucksack, | 0:02:27 | 0:02:30 | |

one that his great-grandfather had bought in a junk shop. | 0:02:30 | 0:02:33 | |

He asked my father to look after it for him. | 0:02:33 | 0:02:36 | |

It was one of only two portraits painted of JS Bach in his lifetime. | 0:02:36 | 0:02:41 | |

So I passed it every day of my life, until I was ten, | 0:02:44 | 0:02:47 | |

when the painting was sold and moved to Princeton, New Jersey. | 0:02:47 | 0:02:52 | |

This is the first time I've seen it since 1953. | 0:02:52 | 0:02:56 | |

What's so striking to me, seeing it again, is the intensity of his gaze. | 0:02:56 | 0:03:00 | |

Those eyes. It's just extraordinary, they're so penetrative. | 0:03:00 | 0:03:06 | |

I still feel there's a division between the upper half | 0:03:06 | 0:03:10 | |

of his face and the bottom half. | 0:03:10 | 0:03:12 | |

The upper half is so intense, it's got that beetle-browed, | 0:03:12 | 0:03:17 | |

slightly myopic look. | 0:03:17 | 0:03:20 | |

Below that, you see somebody quite different, | 0:03:20 | 0:03:23 | |

somebody much more approachable, somebody who enjoyed | 0:03:23 | 0:03:28 | |

the good things of life, a bon viveur, who enjoyed his tobacco | 0:03:28 | 0:03:32 | |

and his wine and his beer, | 0:03:32 | 0:03:34 | |

and there's plenty of records of what he drank. | 0:03:34 | 0:03:37 | |

And the father of 20 children and two wives. | 0:03:37 | 0:03:41 | |

We know pitifully few hard facts about Bach. | 0:03:43 | 0:03:46 | |

There's very little to go on, and only a handful of personal letters. | 0:03:46 | 0:03:51 | |

But, as in any good detective story, it's often the gaps, | 0:03:51 | 0:03:55 | |

the seeming contradictions in the tale, | 0:03:55 | 0:03:57 | |

that are as suggestive and intriguing | 0:03:57 | 0:03:59 | |

as the hard evidence available. | 0:03:59 | 0:04:02 | |

We do know that Johann Sebastian was born on 21 March 1685, | 0:04:05 | 0:04:10 | |

in Eisenach, in the middle of modern-day Germany. | 0:04:10 | 0:04:15 | |

This is the so-called Bachhaus, now a museum devoted to him. | 0:04:21 | 0:04:26 | |

Until recently, it billed itself as the house where Bach was born | 0:04:26 | 0:04:30 | |

and where he grew up. We now know that's definitely not the case. | 0:04:30 | 0:04:34 | |

As with so much of his life, | 0:04:34 | 0:04:36 | |

exactly where Bach was born remains a mystery. | 0:04:36 | 0:04:39 | |

Johann Sebastian was baptised here, at two days old, | 0:04:43 | 0:04:46 | |

in St George's Church in Eisenach. | 0:04:46 | 0:04:48 | |

Later, he sang here in the choir. | 0:04:50 | 0:04:53 | |

As a child, he's said to have had an unusually fine treble voice. | 0:04:53 | 0:04:56 | |

200 years before him, there was another chorister | 0:04:57 | 0:05:00 | |

who stood in exactly the same place. | 0:05:00 | 0:05:03 | |

Now that was Martin Luther. | 0:05:03 | 0:05:05 | |

And Luther created a revolution here in this part of Germany. | 0:05:05 | 0:05:12 | |

Bach's whole life was to be | 0:05:12 | 0:05:14 | |

profoundly influenced by Luther's Reformation. | 0:05:14 | 0:05:17 | |

Luther set in train a new way of worship. | 0:05:17 | 0:05:20 | |

It totally transformed the role of language and music in church. | 0:05:20 | 0:05:24 | |

Bach's own music was filtered through his strongly held | 0:05:24 | 0:05:27 | |

Lutheran beliefs and upbringing. | 0:05:27 | 0:05:32 | |

Luther preached his Reformation here in the Georgenkirche in 1521. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:37 | |

Then he disappeared. | 0:05:37 | 0:05:40 | |

Actually, he hadn't gone far. | 0:05:41 | 0:05:43 | |

In fact, in the greatest of secrecy, Luther was in hiding up here | 0:05:43 | 0:05:47 | |

in the Wartburg, the imposing castle that looms above the town of Eisenach. | 0:05:47 | 0:05:51 | |

His Reformation had made Luther the most wanted man in Europe. | 0:06:02 | 0:06:09 | |

So, this is the little room where Luther lived. | 0:06:09 | 0:06:13 | |

For ten months here he was holed up, imprisoned, really, for his own good, | 0:06:13 | 0:06:18 | |

because he was on the run from the Pope, from the Emperor. | 0:06:18 | 0:06:21 | |

He was desperately constipated. | 0:06:23 | 0:06:25 | |

"The Lord has struck me in the rear," he said. | 0:06:25 | 0:06:29 | |

And he thought that the devil was pelting him | 0:06:29 | 0:06:31 | |

with walnuts from the ceiling. | 0:06:31 | 0:06:33 | |

Luther decided that his best weapon | 0:06:37 | 0:06:40 | |

to use against the devil was black ink. | 0:06:40 | 0:06:43 | |

And, in a matter of weeks, he sat down at this desk | 0:06:43 | 0:06:47 | |

and he wrote a translation, from the Greek, | 0:06:47 | 0:06:53 | |

of the New Testament. | 0:06:53 | 0:06:55 | |

And it wasn't just any old German, he decided that he needed | 0:06:55 | 0:06:59 | |

to amalgamate 18 different dialects and, in effect, | 0:06:59 | 0:07:04 | |

he established the roots of the German language as we know it. | 0:07:04 | 0:07:09 | |

Not only did Luther want the Bible to be in the language of the people, | 0:07:09 | 0:07:12 | |

he also wanted them to be able to join in the music, | 0:07:12 | 0:07:16 | |

something that, in the Catholic church, | 0:07:16 | 0:07:18 | |

was much more the province of trained choirs. | 0:07:18 | 0:07:21 | |

Luther was convinced that music added extra expression | 0:07:24 | 0:07:28 | |

and eloquence to the biblical text. | 0:07:28 | 0:07:31 | |

"The notes make the words come alive," he wrote. | 0:07:31 | 0:07:35 | |

"In fact, without music, man is little more than a stone." | 0:07:35 | 0:07:41 | |

So, the words appealed to the intellect, | 0:07:41 | 0:07:43 | |

and the music appealed to the passions. | 0:07:43 | 0:07:46 | |

And, besides, why should the devil have all the good tunes? | 0:07:46 | 0:07:49 | |

Luther and his followers made sure he didn't. | 0:07:49 | 0:07:52 | |

They choraled secular tunes that everybody knew, | 0:07:52 | 0:07:56 | |

including quite earthy love songs, and then set them to new words | 0:07:56 | 0:08:00 | |

so that the congregation could belt them out in church. | 0:08:00 | 0:08:05 | |

Hymns, or chorales, written by Luther | 0:08:05 | 0:08:06 | |

and his followers became absolutely central to Protestant worship, | 0:08:06 | 0:08:10 | |

and of course to the music of Bach. | 0:08:10 | 0:08:13 | |

The impact of the reformer Luther | 0:08:17 | 0:08:19 | |

on the impressionable young Bach was immeasurable. | 0:08:19 | 0:08:23 | |

It shaped his whole view of the world, | 0:08:23 | 0:08:26 | |

it bolstered his sense of worth | 0:08:26 | 0:08:28 | |

as a craftsman musician, and reinforced his service to the Church. | 0:08:28 | 0:08:34 | |

It's such an announcement, | 0:08:34 | 0:08:36 | |

a proclamation of the arrival on Earth of the Christ child. | 0:08:36 | 0:08:39 | |

Relish the words. Relish them. | 0:08:39 | 0:08:41 | |

So, "Brich an..." | 0:08:41 | 0:08:43 | |

Bach's destiny was to become a musician. | 0:09:46 | 0:09:49 | |

Music was the family business. | 0:09:49 | 0:09:51 | |

In this part of Germany, in the heart of the Thuringian forest, | 0:09:51 | 0:09:56 | |

the Bach family were thick on the ground. | 0:09:56 | 0:09:59 | |

They provided a support system to each other, | 0:09:59 | 0:10:02 | |

and they carved up the different roles of organist and cantor, | 0:10:02 | 0:10:06 | |

and Hausmann - the head of the local wind band - between them. | 0:10:06 | 0:10:10 | |

And, in fact, they became almost | 0:10:10 | 0:10:12 | |

so important here that the word Bach and musician became synonymous. | 0:10:12 | 0:10:18 | |

MUSIC: "Quodlibet, BWV 524" by JS Bach | 0:10:18 | 0:10:21 | |

The Bach clan knew how to let their hair down, | 0:10:25 | 0:10:27 | |

and often got together for raucous family celebrations. | 0:10:27 | 0:10:32 | |

Sebastian, the youngest of eight brothers and sisters, was thus | 0:10:32 | 0:10:35 | |

surrounded by music at home, in church and in school. | 0:10:35 | 0:10:41 | |

I have in my hands what was probably the most precious book of Bach's childhood. | 0:10:41 | 0:10:47 | |

It's certainly the one he used every day of his life | 0:10:47 | 0:10:49 | |

until he left Eisenach. | 0:10:49 | 0:10:52 | |

It's the Eisenachisches Gesangbuch, the songbook used in church | 0:10:52 | 0:10:57 | |

and used in school. | 0:10:57 | 0:10:58 | |

It has wonderful copper engravings which show David and Solomon in the Temple, | 0:10:58 | 0:11:06 | |

surrounded by their temple musicians, | 0:11:06 | 0:11:09 | |

and the connections that Bach | 0:11:09 | 0:11:10 | |

must've made in his mind, between his family | 0:11:10 | 0:11:14 | |

of the most famous musicians in the area, with a long, | 0:11:14 | 0:11:17 | |

dynastic lineage going all the way back to Solomon. | 0:11:17 | 0:11:22 | |

Because he wrote so many masterpieces of sacred music, | 0:11:24 | 0:11:27 | |

in the 19th-century, | 0:11:27 | 0:11:28 | |

religiously-inclined writers | 0:11:28 | 0:11:30 | |

liked to picture Bach as a saintly figure, | 0:11:30 | 0:11:32 | |

a kind of fifth Evangelist | 0:11:32 | 0:11:34 | |

to match the goody two-shoes image of his childhood. | 0:11:34 | 0:11:38 | |

But, in recent years, this picture has started to change. | 0:11:38 | 0:11:42 | |

This is a book containing the records of Bach's school performance, | 0:11:42 | 0:11:47 | |

and it gives us his syllabus of classes that he attended, | 0:11:47 | 0:11:51 | |

and it also shows that, for example, in the third year, | 0:11:51 | 0:11:55 | |

he came 46th out of 89 pupils, | 0:11:55 | 0:11:59 | |

and what's more, it tells us that he missed 96 separate classes. | 0:11:59 | 0:12:05 | |

This is a fascinating document, | 0:12:08 | 0:12:10 | |

because it's somehow slipped under the radar. | 0:12:10 | 0:12:13 | |

It's a report on school conditions in the Latin school | 0:12:13 | 0:12:16 | |

where Bach was a pupil, and it shows the lack of textbooks, | 0:12:16 | 0:12:21 | |

the overcrowding, the cheeking of the masters, | 0:12:21 | 0:12:24 | |

the throwing of bricks through the windows, | 0:12:24 | 0:12:27 | |

all sorts of proto-hooliganism | 0:12:27 | 0:12:29 | |

and it's been, kind of, neatly ironed out of all the biographies, | 0:12:29 | 0:12:34 | |

so it's really interesting to come to light now. | 0:12:34 | 0:12:37 | |

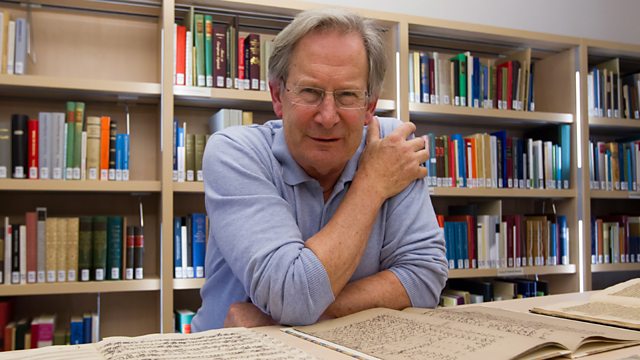

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany, | 0:12:41 | 0:12:45 | |

more documents have come to light that greatly enhance | 0:12:45 | 0:12:49 | |

our knowledge of Bach. | 0:12:49 | 0:12:51 | |

In particular, the Bach Archives in Leipzig have made huge strides | 0:12:51 | 0:12:54 | |

in discovering more about the composer's working methods, | 0:12:54 | 0:12:57 | |

and, for the first time, opened their doors to researchers. | 0:12:57 | 0:13:02 | |

All the significant documents about Bach, many originals, | 0:13:02 | 0:13:05 | |

some copies, are here. | 0:13:05 | 0:13:08 | |

When Bach was 50, he suddenly got a fascination for family roots | 0:13:08 | 0:13:13 | |

and family trees, genealogy, | 0:13:13 | 0:13:15 | |

so, he wanted to give himself legitimacy in some way. | 0:13:15 | 0:13:19 | |

And here's an example, and it shows the whole Bach family, | 0:13:19 | 0:13:24 | |

starting with the legendary figure of Veit Bach, | 0:13:24 | 0:13:27 | |

who arrived from Hungary in the middle of the 16th century, | 0:13:27 | 0:13:29 | |

and it goes all the way through to Bach himself, | 0:13:29 | 0:13:33 | |

who's over here, and then his children, and his grandchildren. | 0:13:33 | 0:13:37 | |

You'll notice every single member of the Bach family is a man. | 0:13:37 | 0:13:42 | |

All blokes, not a single woman. | 0:13:42 | 0:13:46 | |

But mothers, sisters | 0:13:46 | 0:13:47 | |

and aunts must have participated in the family music-making. | 0:13:47 | 0:13:51 | |

So, was it nature or nurture that we have to thank for the genius of Bach? | 0:13:51 | 0:13:56 | |

When he was 50, he did a family tree and he also assembled | 0:13:56 | 0:14:00 | |

pieces of his ancestors' music, and there was one person | 0:14:00 | 0:14:04 | |

that he singled out as being a profound composer, | 0:14:04 | 0:14:07 | |

and another one who he singled out as being an able composer, | 0:14:07 | 0:14:10 | |

but there obviously wasn't anybody of enormous quality | 0:14:10 | 0:14:13 | |

until he came along, | 0:14:13 | 0:14:15 | |

and yet he was one of five brothers, four brothers - how come, he, | 0:14:15 | 0:14:19 | |

and not the others, popped up above the parapet? | 0:14:19 | 0:14:22 | |

He's such a good example, because he really undermines | 0:14:22 | 0:14:26 | |

any simplistic explanation of his genius, of genius. | 0:14:26 | 0:14:30 | |

I mean, if you had a genetic explanation, | 0:14:30 | 0:14:34 | |

the genes would have gone throughout the Bach family - in fact, | 0:14:34 | 0:14:37 | |

why did they take so long to generate Bach, | 0:14:37 | 0:14:40 | |

you know, so many generations, | 0:14:40 | 0:14:41 | |

and I think all of these more general explanations, | 0:14:41 | 0:14:45 | |

on the basis of genes, or even on the basis of the musical culture | 0:14:45 | 0:14:49 | |

that surrounds him, do not deliver the singular genius he was. | 0:14:49 | 0:14:52 | |

And it's a pity in a way, | 0:14:52 | 0:14:54 | |

we can't accept the singularity of people who are manifestly unique. | 0:14:54 | 0:14:59 | |

We can't bear the idea that genius is unexplained. | 0:14:59 | 0:15:04 | |

But that's not to say Bach was self-taught. | 0:15:04 | 0:15:07 | |

His father's cousin, Johann Christoph, | 0:15:07 | 0:15:10 | |

was the profound composer he referred to. | 0:15:10 | 0:15:13 | |

His music, only recently rediscovered, | 0:15:13 | 0:15:15 | |

is the link between Bach and the earlier German tradition. | 0:15:15 | 0:15:19 | |

Johann Christoph may also have been Sebastian's first teacher | 0:15:21 | 0:15:25 | |

at the organ, an instrument he made his own. | 0:15:25 | 0:15:29 | |

But Johan Christoph's life was a cautionary tale. | 0:15:29 | 0:15:33 | |

In a sense, the life of Johann Christoph Bach | 0:15:33 | 0:15:37 | |

exemplifies the problems that musicians had at the time. | 0:15:37 | 0:15:41 | |

They shuttled between the service of the Church, or of the court, | 0:15:41 | 0:15:47 | |

or occasionally of the municipality, and in Christoph's case, | 0:15:47 | 0:15:51 | |

he had all manner of domestic problems - he was shunted, | 0:15:51 | 0:15:56 | |

also, from pillar to post here in the town, | 0:15:56 | 0:15:59 | |

the town wouldn't give him a proper dwelling, | 0:15:59 | 0:16:03 | |

he had illness in his family, he was underpaid and he was | 0:16:03 | 0:16:08 | |

thoroughly querulous and miserable about it, and died in penury. | 0:16:08 | 0:16:12 | |

But there is another side to it, and this is one that Sebastian | 0:16:12 | 0:16:17 | |

may well have picked up from his elder cousin. | 0:16:17 | 0:16:19 | |

Which is, that as a composer, you can channel all that frustration, | 0:16:19 | 0:16:25 | |

and disappointment into music, | 0:16:25 | 0:16:29 | |

and the marvellous thing is about Johann Christoph's music, | 0:16:29 | 0:16:32 | |

and Sebastian's music, is that it has this wonderfully consoling | 0:16:32 | 0:16:37 | |

and uplifting quality to it. | 0:16:37 | 0:16:39 | |

Most of all, Bach's music offers us balm and comfort in bereavement. | 0:16:47 | 0:16:52 | |

The subject of death appears again and again in his music, | 0:16:52 | 0:16:56 | |

as it did in his own life. | 0:16:56 | 0:16:59 | |

This is the town cemetery, | 0:16:59 | 0:17:01 | |

and Eisenach's old city walls are here on the right, | 0:17:01 | 0:17:05 | |

and just beyond it is the school where Bach went, the old Dominican cloister. | 0:17:05 | 0:17:11 | |

Somewhere here, in unmarked graves, are those of his parents, | 0:17:11 | 0:17:16 | |

Elisabeth and Ambrosius. | 0:17:16 | 0:17:20 | |

Elisabeth died when Bach was scarcely nine years old. | 0:17:20 | 0:17:23 | |

And then nine months later, his father, Ambrosius, died, as well. | 0:17:23 | 0:17:28 | |

Bach, as the youngest son, | 0:17:28 | 0:17:30 | |

and member of the parish choir, had to witness the whole event | 0:17:30 | 0:17:36 | |

and sing while the ceremony was going on, | 0:17:36 | 0:17:39 | |

and the slow tolling of the bells, | 0:17:39 | 0:17:42 | |

and as the coffin was lowered into the grave, | 0:17:42 | 0:17:46 | |

he and his fellow choristers sang Luther's words, | 0:17:46 | 0:17:50 | |

"Mitten wir im Leben sind" - | 0:17:50 | 0:17:53 | |

"In the midst of life, we're in death." | 0:17:53 | 0:17:57 | |

His whole world must have collapsed. | 0:17:57 | 0:18:00 | |

His first wife was to die at the age of just 35. | 0:18:01 | 0:18:06 | |

Even in an age of high infant mortality, of his 20 children, | 0:18:06 | 0:18:10 | |

only ten were to reach adulthood. | 0:18:10 | 0:18:14 | |

After his parents died, | 0:18:16 | 0:18:19 | |

Sebastian and his elder brother Jakob went to live with a sibling | 0:18:19 | 0:18:22 | |

they hardly knew, Johann Christoph, 14 years older than Sebastian. | 0:18:22 | 0:18:26 | |

He was a church organist at Ohrdruf, only 30 miles up the road, | 0:18:26 | 0:18:31 | |

but it could have been a world away. | 0:18:31 | 0:18:33 | |

I have come across documents in the local archives that show that | 0:18:34 | 0:18:38 | |

conditions in Sebastian's school in Ohrdruf were | 0:18:38 | 0:18:41 | |

every bit as deplorable as in the one he had left behind in Eisenach. | 0:18:41 | 0:18:45 | |

Roughianism and loutish behaviour were rife here, too, | 0:18:45 | 0:18:48 | |

and there was a sadistic teacher. | 0:18:48 | 0:18:51 | |

But, curiously, Bach's grades improved. | 0:18:51 | 0:18:54 | |

Bach was the youngest son of quite a big family, | 0:18:54 | 0:18:57 | |

and then suddenly he lost both parents before his tenth birthday. | 0:18:57 | 0:19:00 | |

He then went to live with his elder brother. | 0:19:00 | 0:19:04 | |

How much of a trauma can it have been? | 0:19:04 | 0:19:08 | |

What you're describing is a triple bereavement. | 0:19:08 | 0:19:10 | |

There is losing the parents, losing the home, new town, | 0:19:10 | 0:19:13 | |

new place, I would say that is pretty difficult for any child. | 0:19:13 | 0:19:19 | |

We do have a lot of research showing that this kind of | 0:19:19 | 0:19:22 | |

early bereavement and uprooting can scar people for life. | 0:19:22 | 0:19:27 | |

Do you think his school grades are relevant and interesting here, | 0:19:27 | 0:19:31 | |

because, when he was in Eisenach, | 0:19:31 | 0:19:33 | |

when he was still with his parents, he played truant an awful lot. | 0:19:33 | 0:19:39 | |

After he moves into his elder brother's house, | 0:19:39 | 0:19:41 | |

his school grades rocket, they go way up, | 0:19:41 | 0:19:44 | |

so there's a big change there, | 0:19:44 | 0:19:46 | |

do think that's to do with the orphanhood? | 0:19:46 | 0:19:49 | |

Again, I'm speculating. But what I'm hearing here is that there was | 0:19:49 | 0:19:53 | |

a horrible, horrible environment in the school, | 0:19:53 | 0:19:55 | |

but maybe there was a little protection from the home. | 0:19:55 | 0:19:58 | |

Then he loses the home. | 0:19:58 | 0:19:59 | |

So now the whole world is a dog-eat-dog situation. | 0:19:59 | 0:20:02 | |

There's only one person he can rely on, and that's himself. | 0:20:02 | 0:20:06 | |

Which would explain why he has to be good at school now, doesn't he? | 0:20:06 | 0:20:10 | |

He has to, because, basically, if you show weakness, | 0:20:10 | 0:20:14 | |

if you are weak, you suffer and you go under. | 0:20:14 | 0:20:16 | |

At the age of 15, Bach was awarded a singing scholarship | 0:20:19 | 0:20:22 | |

at a school in Luneburg, 230 miles to the north. | 0:20:22 | 0:20:26 | |

He walked the whole way with a schoolfriend, Georg Erdmann, | 0:20:26 | 0:20:29 | |

who would re-enter the Bach story 30 years later. | 0:20:29 | 0:20:32 | |

Bach spent three years in Luneburg, from the age of 15 to 18. | 0:20:40 | 0:20:45 | |

His voice would have broken almost as soon as he got there, | 0:20:45 | 0:20:48 | |

so what was he doing in the meantime? | 0:20:48 | 0:20:50 | |

This is one of the great puzzles of Bach's life. | 0:20:50 | 0:20:53 | |

One thing we do know is that, while he was at Luneburg, | 0:20:53 | 0:20:56 | |

Bach was acquainted with one of Germany's leading musical figures, | 0:20:56 | 0:20:59 | |

Georg Bohm, a composer and renowned organist, | 0:20:59 | 0:21:03 | |

also born in Thuringia, like Bach himself. | 0:21:03 | 0:21:06 | |

This is a letter Carl Philipp Emanuel wrote to Bach's first biographer, | 0:21:10 | 0:21:15 | |

Johann Nikolaus Forkel, | 0:21:15 | 0:21:18 | |

telling him all the bits and pieces he could remember about his father. | 0:21:18 | 0:21:23 | |

The particularly interesting thing is when he refers to his former teacher, | 0:21:23 | 0:21:29 | |

Georg Bohm, he crosses it out. | 0:21:29 | 0:21:31 | |

Why, having written that Bohm was his father's teacher, | 0:21:34 | 0:21:37 | |

did Emanuel think better of it and erase the reference? | 0:21:37 | 0:21:40 | |

In 2005, a suggestive new clue came to light. | 0:21:42 | 0:21:46 | |

Some leaves of organ tablature, | 0:21:48 | 0:21:50 | |

for many years wrongly catalogued in a German library, | 0:21:50 | 0:21:53 | |

were rediscovered by Leipzig Bach archivist Michael Maul. | 0:21:53 | 0:21:57 | |

When I read the Latin phrase at the end of the manuscript, | 0:21:58 | 0:22:04 | |

"Copied after a manuscript of Georg Bohm in the year 1700 in Luneburg." | 0:22:04 | 0:22:11 | |

I know one person who was in 1700 in Luneburg | 0:22:11 | 0:22:15 | |

and was very interested in very good organ music. | 0:22:15 | 0:22:19 | |

And that's the young JS Bach. | 0:22:19 | 0:22:21 | |

After comparing the manuscript with the other examples, | 0:22:21 | 0:22:26 | |

we can be absolutely sure that no-one else than Bach | 0:22:26 | 0:22:30 | |

is the writer of these manuscripts. | 0:22:30 | 0:22:32 | |

This is the missing piece in the puzzle, isn't it? | 0:22:32 | 0:22:35 | |

It says that he wrote this on paper belonging to Georg Bohm. | 0:22:35 | 0:22:40 | |

He went and maybe became a student or an apprentice to Georg Bohm. | 0:22:40 | 0:22:46 | |

-Yes. -After his supervision, he wrote out this very difficult piece, | 0:22:46 | 0:22:52 | |

which proves that he played this music. So he was already a virtuoso. | 0:22:52 | 0:22:55 | |

Did Emanuel suddenly remember that his father, for some reason, | 0:23:01 | 0:23:04 | |

didn't wish his relationship with Georg Bohm to be known? | 0:23:04 | 0:23:08 | |

Did he acknowledge that he learnt from other people? | 0:23:08 | 0:23:10 | |

Did he acknowledge their greatness? | 0:23:10 | 0:23:13 | |

This is fascinating, because when he made remarks | 0:23:13 | 0:23:15 | |

about possible teachers, his son, Emanuel, just erased them. | 0:23:15 | 0:23:21 | |

So Bach didn't want that to be known. | 0:23:21 | 0:23:23 | |

He wanted everybody to know that he'd done it entirely on his own, | 0:23:23 | 0:23:27 | |

off his own back. | 0:23:27 | 0:23:28 | |

If he had this assumption that you have got to have power | 0:23:28 | 0:23:31 | |

and you should never show weakness, | 0:23:31 | 0:23:34 | |

he would be very poor in acknowledging those sources. | 0:23:34 | 0:23:37 | |

At the age of 18, Bach, as well as being a virtuoso organist, | 0:23:37 | 0:23:42 | |

was a competent violinist. | 0:23:42 | 0:23:44 | |

In 1703, he left Luneburg to return to the family stamping ground. | 0:23:44 | 0:23:49 | |

In Arnstadt, only 30 miles from where Sebastian was born, | 0:23:49 | 0:23:52 | |

the city fathers had put a tax on beer, | 0:23:52 | 0:23:55 | |

to pay for a brand-new organ for the Neukirchen. | 0:23:55 | 0:23:58 | |

Bach was hired to test the new organ | 0:23:59 | 0:24:01 | |

and to play it in audition in front of the thirsty citizens. | 0:24:01 | 0:24:05 | |

He landed the job on more money than his father had ever earned. | 0:24:05 | 0:24:09 | |

But there was a catch the council insisted he provide new music. | 0:24:09 | 0:24:13 | |

All he had at his disposal was a rag, tag and bobtail band | 0:24:15 | 0:24:19 | |

made up of mature students. | 0:24:19 | 0:24:21 | |

Thus, Bach began his career as a composer, | 0:24:21 | 0:24:24 | |

but not in exactly auspicious circumstances. | 0:24:24 | 0:24:27 | |

He wrote a cantata, his first, | 0:24:27 | 0:24:30 | |

in which there's a very important bassoon obbligato, | 0:24:30 | 0:24:34 | |

a solo for the bassoon, in three of the movements. | 0:24:34 | 0:24:38 | |

It was a banana skin. | 0:24:38 | 0:24:40 | |

The bassoon part starts innocuously enough, | 0:24:42 | 0:24:45 | |

honking away at a steady old lick. | 0:24:45 | 0:24:48 | |

But then comes a bassoonist's worst nightmare. | 0:24:48 | 0:24:52 | |

HE PLAYS VERY QUICKLY | 0:24:52 | 0:24:54 | |

In the space of about two-and-a-half bars, he sends the bassoon | 0:25:02 | 0:25:06 | |

through a whole list of different keys, | 0:25:06 | 0:25:10 | |

involving very, very complicated fingerings. | 0:25:10 | 0:25:13 | |

Deliberately or not, Bach had set a trap for his resident bassoonist. | 0:25:13 | 0:25:18 | |

He was writing for a fellow called Geyersbach | 0:25:18 | 0:25:23 | |

who, in rehearsal, made a complete hash of it. | 0:25:23 | 0:25:27 | |

And Bach was exasperated to the point where he called him | 0:25:27 | 0:25:31 | |

a "Zippelfagottist", which can be translated variously | 0:25:31 | 0:25:35 | |

as a nanny goat bassoon or a greenhorn bassoon. | 0:25:35 | 0:25:39 | |

But, in reality, Bach was calling him a prick. | 0:25:39 | 0:25:43 | |

Yet another translation is | 0:25:45 | 0:25:47 | |

"Bassoonist breaking wind after eating a green onion." | 0:25:47 | 0:25:51 | |

However Geyersbach understood the term, | 0:25:51 | 0:25:53 | |

he didn't like what he was hearing. | 0:25:53 | 0:25:54 | |

The insult clearly rankled, and Geyersbach plotted his revenge. | 0:25:57 | 0:26:02 | |

He and his cronies, well-oiled after a party at a christening, | 0:26:02 | 0:26:07 | |

sat in wait for Bach, here in the town square. | 0:26:07 | 0:26:13 | |

Bach was making his way back from playing music at the castle, | 0:26:13 | 0:26:17 | |

Neideck Castle, and was taken completely by surprise. | 0:26:17 | 0:26:22 | |

Geyersbach came up to him and demanded an apology, | 0:26:22 | 0:26:25 | |

and then took his cudgel and hit Bach, smack across the face. | 0:26:25 | 0:26:29 | |

Bach, in self defence, drew his rapier | 0:26:29 | 0:26:32 | |

and there was a scuffle, a major scuffle. | 0:26:32 | 0:26:35 | |

It was only the other students who eventually stopped the whole thing. | 0:26:35 | 0:26:39 | |

No doubt to Bach's fury, the Church council sided with Geyersbach, | 0:26:42 | 0:26:46 | |

according to the records. | 0:26:46 | 0:26:48 | |

And that was far from the last of the problems. | 0:26:48 | 0:26:51 | |

Bach was accused of introducing strange harmonies | 0:26:51 | 0:26:54 | |

into his organ music which upset the old dears of the parish. | 0:26:54 | 0:26:58 | |

He played either far too long or not long enough, | 0:26:58 | 0:27:01 | |

and he slipped off down to the pub. | 0:27:01 | 0:27:04 | |

Once, he smuggled a strange girl into his organ loft to make music. | 0:27:04 | 0:27:08 | |

The final straw came | 0:27:08 | 0:27:11 | |

when he asked for four weeks' leave to visit the renowned organist | 0:27:11 | 0:27:14 | |

Buxtehude, walking the whole 260 miles up to Lubeck. | 0:27:14 | 0:27:19 | |

In fact, he was away four months, not four weeks, | 0:27:19 | 0:27:23 | |

and was airily dismissive when he was asked to explain himself. | 0:27:23 | 0:27:27 | |

What we now see is patterns of behaviour that had their origins | 0:27:27 | 0:27:32 | |

in the unhealthy environment of his early schooling, | 0:27:32 | 0:27:36 | |

first in Eisenach and then in Ohrdruf. | 0:27:36 | 0:27:38 | |

Patterns of anger, patterns of dealing with authority | 0:27:38 | 0:27:44 | |

in a very surly and uncompromising way, | 0:27:44 | 0:27:47 | |

impatience, and a kind of self-assuredness | 0:27:47 | 0:27:52 | |

that was bound to rub people up the wrong way. | 0:27:52 | 0:27:54 | |

# Gott! | 0:27:54 | 0:27:56 | |

# Gott! | 0:27:56 | 0:27:59 | |

# Gott ist mein Koenig. # | 0:27:59 | 0:28:01 | |

Bach is commemorated in Arnstadt by this curious recent statue | 0:28:02 | 0:28:06 | |

in "Jack the Lad" pose, | 0:28:06 | 0:28:08 | |

perhaps in a nod to his feisty and fractious stay here. | 0:28:08 | 0:28:11 | |

His time in Arnstadt came to an end when, in 1707, | 0:28:16 | 0:28:21 | |

he was offered a new post 50 miles up the road in Muhlhausen. | 0:28:21 | 0:28:24 | |

The city had been thriving but it was Bach's bad luck | 0:28:26 | 0:28:29 | |

to arrive just after a disastrous fire had wreaked havoc in the city. | 0:28:29 | 0:28:34 | |

Caught up in a local dispute between the clergy, | 0:28:34 | 0:28:37 | |

Bach moved on in less than a year, but two significant things happened. | 0:28:37 | 0:28:41 | |

First, aged 22, he married his cousin, Maria Barbara. | 0:28:41 | 0:28:45 | |

And then, he wrote one of the most important documents we have. | 0:28:45 | 0:28:49 | |

Here's a letter that Bach wrote to the Muhlhausen town council | 0:28:49 | 0:28:54 | |

explaining the reasons why he handed in his resignation, | 0:28:54 | 0:28:59 | |

and the interesting thing from our point of view is that he defines | 0:28:59 | 0:29:02 | |

his "Endzweck" as he called it, his final ambition, his goal in life. | 0:29:02 | 0:29:07 | |

The key phrase is "a well-regulated church music to the glory of God". | 0:29:08 | 0:29:13 | |

Germany was on the brink of the Enlightenment. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:18 | |

The Scientific Revolution had been in full swing | 0:29:18 | 0:29:21 | |

for over a century, but superstition was still rife. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:24 | |

Here, as late as the 1730s, witches were being burned at the stake. | 0:29:24 | 0:29:28 | |

The Thirty Years' War had ended in 1648, and in its wake | 0:29:29 | 0:29:33 | |

came a strong revival of Lutheranism. | 0:29:33 | 0:29:35 | |

Bach took it upon himself to lay down | 0:29:35 | 0:29:38 | |

the New and the Old Testament Commandments with renewed force. | 0:29:38 | 0:29:42 | |

In 1708, Bach left Muhlhausen for the elegant Court of Weimar. | 0:31:18 | 0:31:24 | |

This was a real turning point. For the first time in his life, | 0:31:24 | 0:31:27 | |

he was able to call on good quality musicians. | 0:31:27 | 0:31:30 | |

But as so often in his career, there was a snag. | 0:31:30 | 0:31:32 | |

In fact, there were two of them. Weimar was ruled by a pair of dukes, | 0:31:32 | 0:31:37 | |

an uncle and nephew team. It was a recipe for disaster. | 0:31:37 | 0:31:41 | |

The musicians were employed by both, but the uncle made it known | 0:31:41 | 0:31:47 | |

to the musicians that if they played for his nephew, | 0:31:47 | 0:31:50 | |

they would be liable to be flogged, dismissed out of hand. | 0:31:50 | 0:31:53 | |

In fact, there was one poor horn player who was | 0:31:53 | 0:31:56 | |

dismissed on the spot, | 0:31:56 | 0:31:57 | |

flogged, and then eventually hung as an example - | 0:31:57 | 0:32:01 | |

terrible example - to all the other musicians, | 0:32:01 | 0:32:03 | |

what would happen if they stepped out of line. | 0:32:03 | 0:32:05 | |

One might imagine that in such a fraught, tense situation, | 0:32:14 | 0:32:18 | |

nothing creative could've come out of Bach's time in Weimar, | 0:32:18 | 0:32:21 | |

but of course, the opposite is true. | 0:32:21 | 0:32:23 | |

It was a hugely stimulating time for him. | 0:32:23 | 0:32:26 | |

His first encounter with the Italian music of Vivaldi | 0:32:26 | 0:32:29 | |

and of Corelli and so on. And from Bach's own compositional activity, | 0:32:29 | 0:32:34 | |

it was an enormously important time. | 0:32:34 | 0:32:36 | |

We got the beginnings of his really, really important keyboard works, | 0:32:36 | 0:32:41 | |

and not only that, his cantatas - amazing cantatas - | 0:32:41 | 0:32:45 | |

that he started to write for Weimar, | 0:32:45 | 0:32:48 | |

for the Capella and performed up in the Himmelsburg. | 0:32:48 | 0:32:51 | |

Originally, a cantata was a small, intimate Italian piece | 0:33:00 | 0:33:04 | |

for a solo voice and a couple of instruments. | 0:33:04 | 0:33:08 | |

But soon, it was taken over by German composers in the century | 0:33:08 | 0:33:11 | |

before Bach and was associated with the Lutheran liturgy. | 0:33:11 | 0:33:15 | |

But by the time Bach came along, | 0:33:17 | 0:33:19 | |

it had grown into something almost gargantuan. | 0:33:19 | 0:33:23 | |

His 200 pieces last anything from 25 to 30 minutes each, | 0:33:23 | 0:33:28 | |

occupied a place somewhere between the reading of the lesson | 0:33:28 | 0:33:32 | |

and the sermon, and they reflected the theme of the day, as it were. | 0:33:32 | 0:33:36 | |

You pity the unfortunate preacher who had to follow music as eloquent as this. | 0:33:38 | 0:33:44 | |

Bach demonstrates his fantastic ability to set a scene. | 0:34:33 | 0:34:37 | |

In this case, Jesus knocking at the door of the human heart. | 0:34:37 | 0:34:40 | |

Bach wrote more than 20 cantatas in Weimar, | 0:35:43 | 0:35:46 | |

but having proved his early mastery of the form, he suddenly stopped. | 0:35:46 | 0:35:50 | |

The court's musical director had died, | 0:35:50 | 0:35:53 | |

and when the resulting vacancy was filled by his son, | 0:35:53 | 0:35:56 | |

a musical nullity, and not by Bach, his reaction was to down tools. | 0:35:56 | 0:36:01 | |

He simply stopped composing. | 0:36:01 | 0:36:03 | |

It went from bad to worse. | 0:36:06 | 0:36:07 | |

When Bach asked to leave his employ, the fiery Wilhelm Ernst | 0:36:07 | 0:36:10 | |

had him thrown into jail. | 0:36:10 | 0:36:13 | |

Bach thus became one of the few composers in history | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

to do hard time. | 0:36:16 | 0:36:18 | |

Some of his music, technically the property of his employer, | 0:36:18 | 0:36:21 | |

may have stayed on at Weimar. | 0:36:21 | 0:36:23 | |

70 years later, the Himmelsburg burned to the ground | 0:36:23 | 0:36:27 | |

and Bach's music was lost for ever. | 0:36:27 | 0:36:29 | |

After a month in prison, | 0:36:31 | 0:36:33 | |

Bach headed off to the job he'd been hankering after all along, | 0:36:33 | 0:36:37 | |

that of Kapellmeister. | 0:36:37 | 0:36:39 | |

He joined a music-loving prince, Leopold, at the castle in Kothen, | 0:36:39 | 0:36:44 | |

not far from Weimar, as his music director. | 0:36:44 | 0:36:47 | |

And it was the beginning of a wonderful, new phase in his life. | 0:36:47 | 0:36:50 | |

Five-and-a-half years of relative trouble-free composition. | 0:36:50 | 0:36:55 | |

The first time in his life where he's away from the Church, | 0:36:55 | 0:36:59 | |

he's in a secular environment because he doesn't have to | 0:36:59 | 0:37:02 | |

write church music, Prince Leopold is a Calvinist, | 0:37:02 | 0:37:05 | |

there's no requirements of Lutheran Church music at his court. | 0:37:05 | 0:37:08 | |

Bach is settled with his family and he has a sympathetic | 0:37:08 | 0:37:11 | |

and extremely music-conscious and music-enthusiastic boss. | 0:37:11 | 0:37:17 | |

Bach completed the famous Brandenburg Concertos at Kothen, | 0:37:17 | 0:37:21 | |

as well as a set of solo cello suites which are today | 0:37:21 | 0:37:24 | |

amongst his most popular works. | 0:37:24 | 0:37:26 | |

Just as Bach was for once happy and settled, tragedy struck. | 0:38:36 | 0:38:41 | |

While he was on a trip to Bohemia with the Prince, | 0:38:41 | 0:38:44 | |

the only time Bach ever left Germany, | 0:38:44 | 0:38:47 | |

his wife Maria Barbara died unexpectedly, | 0:38:47 | 0:38:49 | |

and was buried before he returned and could be told of her death. | 0:38:49 | 0:38:53 | |

Their marriage seems to have been a happy one | 0:38:53 | 0:38:55 | |

and this sudden bereavement was another crushing blow for Bach. | 0:38:55 | 0:38:59 | |

No-one knew better than he how terrifyingly unpredictable | 0:39:00 | 0:39:04 | |

an assignation with death could be. | 0:39:04 | 0:39:06 | |

THEY SING IN GERMAN | 0:39:06 | 0:39:08 | |

A year-and-a-half after his first wife died, | 0:39:36 | 0:39:39 | |

Bach married Anna Magdalena, | 0:39:39 | 0:39:41 | |

a professional singer at the Koten court, 16 years his junior. | 0:39:41 | 0:39:45 | |

She was to bear him another 13 children, | 0:39:45 | 0:39:47 | |

seven of whom died in infancy. | 0:39:47 | 0:39:50 | |

For his new wife, and at her request, | 0:39:51 | 0:39:54 | |

Bach gathered together the music of the Anna Magdalena notebooks. | 0:39:54 | 0:39:58 | |

Also at Koten, he began the 48 preludes | 0:39:58 | 0:40:01 | |

and fugues of the Well Tempered Clavier. | 0:40:01 | 0:40:03 | |

It's typical of Bach that to test out a new tuning system, | 0:40:03 | 0:40:07 | |

he wrote two pieces for each key, major and minor. | 0:40:07 | 0:40:11 | |

For me, the driving thing for Bach must have been this obsessive rigour. | 0:40:11 | 0:40:16 | |

This is someone who, I think, | 0:40:16 | 0:40:18 | |

in writing a collection of keyboard works in every key, | 0:40:18 | 0:40:22 | |

I think it's not just that that's available to him. | 0:40:22 | 0:40:25 | |

I think he couldn't possibly have done it any other way. | 0:40:25 | 0:40:28 | |

He would have had to explore every single key and done it again twice. | 0:40:28 | 0:40:32 | |

Bach's inventiveness is proved by a puzzle contained in the music | 0:40:34 | 0:40:37 | |

he's showing us in the famous portrait | 0:40:37 | 0:40:40 | |

I passed every day as a child. | 0:40:40 | 0:40:41 | |

On the face of it, the piece is straightforward enough. | 0:40:41 | 0:40:44 | |

It's incredibly simple, it sounds almost like a nursery rhyme. | 0:40:44 | 0:40:49 | |

But that's the version that we see | 0:40:57 | 0:41:00 | |

as he shows it to us in the portrait. | 0:41:00 | 0:41:03 | |

But from his perspective, what do we see? | 0:41:03 | 0:41:05 | |

Well, if you turned the music up the other way round, | 0:41:05 | 0:41:09 | |

and read it backwards, what you get is this. | 0:41:09 | 0:41:13 | |

In other words, what's in my head and what you see | 0:41:22 | 0:41:25 | |

and what you hear are two different things? | 0:41:25 | 0:41:27 | |

Yeah, I think he's got it like a secret smile. | 0:41:27 | 0:41:30 | |

He's not quite looking at it, is he? He knows something that we don't. | 0:41:30 | 0:41:34 | |

I love the fact it took 100 years for people to start working it out. | 0:41:34 | 0:41:38 | |

The clue is in the title. | 0:41:38 | 0:41:40 | |

It's a piece not for three, but for six voices. | 0:41:40 | 0:41:43 | |

If you move the reverse version by a bar, | 0:41:45 | 0:41:50 | |

you get this incredible six parts, um, | 0:41:50 | 0:41:53 | |

bit of pop music, really. | 0:41:53 | 0:41:55 | |

It's so simple, it's so complex. | 0:42:08 | 0:42:10 | |

Do you subscribe to the view that a lot of his music is numerological, | 0:42:10 | 0:42:16 | |

that it is reflecting not simply just his own name, | 0:42:16 | 0:42:20 | |

but actually that he as a starting mechanism | 0:42:20 | 0:42:23 | |

would rule the paper | 0:42:23 | 0:42:25 | |

and measure out the number of bars he was actually going to use? | 0:42:25 | 0:42:29 | |

Or is that just baloney? | 0:42:29 | 0:42:31 | |

I think it was a hugely creative, | 0:42:31 | 0:42:34 | |

structural mechanism for him. | 0:42:34 | 0:42:37 | |

But that was an intuition | 0:42:37 | 0:42:40 | |

that he had around numbers | 0:42:40 | 0:42:42 | |

and the appeal of numbers for him. | 0:42:42 | 0:42:45 | |

And I think he had an almost obsessive enjoyment of pattern, | 0:42:45 | 0:42:49 | |

which for me is the mark of a scientist as well. | 0:42:49 | 0:42:51 | |

Scientists look for and respond to pattern in nature. | 0:42:51 | 0:42:55 | |

When they find it, they try and categorise it | 0:42:55 | 0:42:57 | |

and put walls around it, and then they try and break the rules. | 0:42:57 | 0:43:00 | |

That's the fun bit, playing with the pattern that they find. | 0:43:00 | 0:43:03 | |

I think it's an intuition that he has, not as a mathematician as such, | 0:43:03 | 0:43:07 | |

but more broadly as a scientist. | 0:43:07 | 0:43:08 | |

In his own lifetime, Bach was far more famous as a performer | 0:43:10 | 0:43:13 | |

than as a composer. | 0:43:13 | 0:43:16 | |

He wrote many pieces for the organ, | 0:43:16 | 0:43:18 | |

an instrument on which he was renowned as an improviser of genius. | 0:43:18 | 0:43:22 | |

He also stretched the boundaries of another instrument he performed on, | 0:43:22 | 0:43:25 | |

writing a series of solo dance suites for the violin. | 0:43:25 | 0:43:29 | |

They are light years ahead of anything that was written | 0:43:31 | 0:43:34 | |

for the solo violin ever before. | 0:43:34 | 0:43:37 | |

He just takes the violin into a completely different realm. | 0:43:37 | 0:43:41 | |

And asks from the violin to do very "un-violinistic" things. | 0:43:42 | 0:43:45 | |

Like triple stops, quadruple stops, | 0:43:45 | 0:43:48 | |

um, polyphonic writing, fugues. | 0:43:48 | 0:43:52 | |

You know, fugues were written for harpsichord | 0:43:52 | 0:43:54 | |

and for organs and orchestras, | 0:43:54 | 0:43:56 | |

but not for one solo violin. | 0:43:56 | 0:43:58 | |

That is storytelling too. | 0:44:27 | 0:44:30 | |

It's a story, if you like, about four notes, D, C, B flat and A. | 0:44:30 | 0:44:33 | |

But it's also a soliloquy. | 0:44:35 | 0:44:38 | |

It's a very dramatic argument, | 0:44:38 | 0:44:41 | |

in a similar way to Hamlet's To Be Or Not To Be, | 0:44:41 | 0:44:44 | |

where you've got a voice arguing with itself | 0:44:44 | 0:44:48 | |

and listening to the counter arguments | 0:44:48 | 0:44:51 | |

and arguing with the counter arguments | 0:44:51 | 0:44:54 | |

and speaking against the counter arguments and so on. | 0:44:54 | 0:44:57 | |

There's the continual wonder | 0:45:10 | 0:45:12 | |

that he brings it about in the way that he does, | 0:45:12 | 0:45:14 | |

which seems to me an absolute miracle. | 0:45:14 | 0:45:18 | |

A piece of such splendour and wonderfulness | 0:45:18 | 0:45:23 | |

that it on its own would convince me that there was a God | 0:45:23 | 0:45:27 | |

if I felt inclined to take that conclusion from it. | 0:45:27 | 0:45:30 | |

Aged 38, Bach was now at the very peak of his powers. | 0:46:18 | 0:46:23 | |

But his lifetime's goal, his Endzweck, | 0:46:25 | 0:46:28 | |

of writing a well-regulated church music to the glory of God, | 0:46:28 | 0:46:32 | |

had been on hold for the past six years. | 0:46:32 | 0:46:36 | |

The opportunities for writing church music to a high standard | 0:46:39 | 0:46:41 | |

only came to Bach very, very rarely in his life. | 0:46:41 | 0:46:46 | |

It didn't come in Arnstadt, it didn't come in Muhlhausen, | 0:46:46 | 0:46:49 | |

it came for a while in Weimar, but not at all in Kothen, | 0:46:49 | 0:46:53 | |

because in Kothen he was working in a Calvinistic court, | 0:46:53 | 0:46:56 | |

and then he had his big break. | 0:46:56 | 0:46:59 | |

Suddenly he saw an opportunity to put his life's ambition into effect. | 0:47:00 | 0:47:04 | |

In 1723, there was a vacancy in Leipzig, | 0:47:05 | 0:47:08 | |

one of the most important cultural centres in Germany | 0:47:08 | 0:47:12 | |

and a thriving cosmopolitan city. | 0:47:12 | 0:47:14 | |

Kantor of the Thomasschule, | 0:47:14 | 0:47:17 | |

one of the oldest and most prestigious choir schools in Europe, | 0:47:17 | 0:47:20 | |

founded in 1212. | 0:47:20 | 0:47:22 | |

This was a full-on boys choir, | 0:47:22 | 0:47:24 | |

the younger ones singing treble and alto, | 0:47:24 | 0:47:28 | |

the older ones tenor and bass, and playing instruments. | 0:47:28 | 0:47:31 | |

It was a great opportunity, | 0:47:33 | 0:47:35 | |

but there were problems in plenty awaiting him. | 0:47:35 | 0:47:39 | |

Besides music, Bach's duties would also include teaching | 0:47:39 | 0:47:43 | |

the boys other school subjects. | 0:47:43 | 0:47:45 | |

But he drew the line at teaching them Latin. | 0:47:45 | 0:47:47 | |

What's more, only a thin party wall | 0:47:47 | 0:47:50 | |

would separate the boys' dormitories and classrooms | 0:47:50 | 0:47:53 | |

from Bach's own private living quarters. | 0:47:53 | 0:47:55 | |

Bach's determination to see his church music project through | 0:47:57 | 0:48:00 | |

eventually overcame his reservations. | 0:48:00 | 0:48:03 | |

In April 1723, he showed up at the Leipzig City Hall | 0:48:03 | 0:48:06 | |

to be interviewed, and offered a job. | 0:48:06 | 0:48:09 | |

So despite all his misgivings, Bach decided to throw in his lot | 0:48:09 | 0:48:13 | |

and to accept the title of Thomaskantor | 0:48:13 | 0:48:17 | |

and Director Of The City Music here in Leipzig. | 0:48:17 | 0:48:20 | |

So he signed his contract and he swore fealty on the Holy Bible. | 0:48:20 | 0:48:27 | |

One of the councillors is on record as saying, | 0:48:30 | 0:48:32 | |

"Since the best man couldn't be obtained, | 0:48:32 | 0:48:35 | |

"mediocre ones would have to be accepted." | 0:48:35 | 0:48:37 | |

The truth is that neither party to this contract could have guessed | 0:48:37 | 0:48:40 | |

what they were letting themselves in for. | 0:48:40 | 0:48:42 | |

In Bach's own words, "hindrance and vexation". | 0:48:42 | 0:48:46 | |

From the moment he set foot in Leipzig, | 0:48:46 | 0:48:48 | |

Bach found himself caught in the political crossfire | 0:48:48 | 0:48:51 | |

between different factions on the city council. | 0:48:51 | 0:48:54 | |

Music, since it carried with it an element of cultural prestige, | 0:48:54 | 0:48:58 | |

formed a part of those political tensions. | 0:48:58 | 0:49:01 | |

On the one hand, on the city council were those loyal to the elector, | 0:49:01 | 0:49:05 | |

who wanted a modern Kapellmeister, | 0:49:05 | 0:49:07 | |

one who could bring real international prestige to the city. | 0:49:07 | 0:49:11 | |

And they were Bach's natural allies. | 0:49:11 | 0:49:13 | |

But opposed to them were the estates party, | 0:49:13 | 0:49:16 | |

who wanted a traditional Kantor, tied into the school system | 0:49:16 | 0:49:20 | |

with all its regulations, and all its teaching duties. | 0:49:20 | 0:49:23 | |

And that throttled Bach's room for manoeuvre. | 0:49:23 | 0:49:26 | |

Before these problems boiled to the surface, Bach set to work. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:32 | |

It used to be thought that his cantatas, | 0:49:32 | 0:49:34 | |

well over 200 of them, and the two great passions | 0:49:34 | 0:49:36 | |

were composed over the whole 27 years he spent in Leipzig. | 0:49:36 | 0:49:40 | |

But in the 1950s, an astonishing discovery was made. | 0:49:41 | 0:49:45 | |

By a careful examination | 0:49:45 | 0:49:47 | |

of the watermarks on the original scores and parts, | 0:49:47 | 0:49:49 | |

scholars discovered that the greater part of the cantatas and passions | 0:49:49 | 0:49:53 | |

were actually produced | 0:49:53 | 0:49:55 | |

in a white-hot frenzy of just three years. | 0:49:55 | 0:49:58 | |

How he kept up that rhythm, how he managed to sustain | 0:49:58 | 0:50:02 | |

that level of intensity and creativity | 0:50:02 | 0:50:05 | |

is just beyond belief. | 0:50:05 | 0:50:07 | |

Particularly when you consider Bach's living conditions. | 0:50:07 | 0:50:10 | |

This is a model of the Thomas School. | 0:50:11 | 0:50:13 | |

The original building was torn down in 1902. | 0:50:13 | 0:50:17 | |

Here, Bach and his family lived right next to the schoolboys. | 0:50:17 | 0:50:20 | |

There wasn't enough room for all the kids | 0:50:20 | 0:50:22 | |

and they slept two to a bed. | 0:50:22 | 0:50:24 | |

There must have been a heck of a lot of background noise. | 0:50:24 | 0:50:28 | |

And he had to concentrate to produce these phenomenal pieces, | 0:50:28 | 0:50:32 | |

and then to supervise their copying out...in his own room? | 0:50:32 | 0:50:37 | |

I think so. | 0:50:37 | 0:50:39 | |

You wonder how he could ever have had any sort of private life | 0:50:39 | 0:50:42 | |

in this sort of outfit, | 0:50:42 | 0:50:45 | |

the conditions being so cramped, and the noise! | 0:50:45 | 0:50:47 | |

And the descriptions of mice and rats | 0:50:47 | 0:50:49 | |

running up and down the staircases as well. | 0:50:49 | 0:50:52 | |

Yeah, they probably had a different concept of private life back then. | 0:50:52 | 0:50:57 | |

Must have done! | 0:50:57 | 0:50:58 | |

Bach didn't just have to write 25 minutes of new music each week. | 0:51:00 | 0:51:04 | |

He also had to get it copied into individual parts for the musicians | 0:51:04 | 0:51:07 | |

to sing and play from. | 0:51:07 | 0:51:08 | |

His already cramped lodgings now had to accommodate | 0:51:08 | 0:51:11 | |

not just his large family, but also cousins | 0:51:11 | 0:51:14 | |

and live-in apprentices to help with the never-ending copying out. | 0:51:14 | 0:51:18 | |

In the pressure cooker atmosphere of the Thomasschule, | 0:51:19 | 0:51:23 | |

and this devastating pace Bach had set himself, | 0:51:23 | 0:51:27 | |

things started to go wrong. | 0:51:27 | 0:51:29 | |

If you look at this, you'll see there's a frenzy in the writing. | 0:51:29 | 0:51:33 | |

It's almost as though he hardly has time to actually put the beams | 0:51:33 | 0:51:37 | |

of the semiquavers and demisemiquavers into the page. | 0:51:37 | 0:51:40 | |

They look like bamboos in a hurricane. | 0:51:40 | 0:51:43 | |

And here's something interesting. | 0:51:43 | 0:51:46 | |

Because this is one of his favourite copyists, | 0:51:46 | 0:51:49 | |

and Bach leaning over to see what he has copied | 0:51:49 | 0:51:52 | |

notices that his name has been misspelt. B-ACCH. | 0:51:52 | 0:51:57 | |

He gives him a hell of a cuff across the earholes, | 0:51:57 | 0:52:01 | |

and the ink flies across the page. | 0:52:01 | 0:52:04 | |

And here's another example - | 0:52:04 | 0:52:07 | |

a cousin, Johann Heinrich, came to Leipzig, | 0:52:07 | 0:52:11 | |

and Bach put him to work immediately in the sweatshop of copying. | 0:52:11 | 0:52:14 | |

He's made a complete hash of it. | 0:52:14 | 0:52:17 | |

He's written out the chorale in the wrong clef and mis-transposed it. | 0:52:17 | 0:52:22 | |

So he has to cross it all out, and Bach himself has to leap in | 0:52:22 | 0:52:25 | |

and write out the chorale neatly at the end. | 0:52:25 | 0:52:28 | |

I mean, what a plonker! | 0:52:28 | 0:52:31 | |

Here, you can see Bach painstakingly trying to repair the damage, | 0:52:31 | 0:52:35 | |

against the clock, to make sure that there weren't terrible errors | 0:52:35 | 0:52:38 | |

on the music stands when it came to their | 0:52:38 | 0:52:40 | |

one and only rehearsal before the cantata was performed. | 0:52:40 | 0:52:43 | |

Bach had constantly to adjust his music to the talents | 0:52:53 | 0:52:56 | |

and skills of his available musicians. | 0:52:56 | 0:52:58 | |

But also he had to lure in university students | 0:52:58 | 0:53:01 | |

in exchange for private music lessons. | 0:53:01 | 0:53:04 | |

There's something about Bach's orthography, his handwriting, | 0:53:04 | 0:53:09 | |

which suggest already the gesture, the direction of a phrase. | 0:53:09 | 0:53:13 | |

In some cases, Bach was forced to | 0:53:13 | 0:53:15 | |

pay for extra musicians from his supplementary earnings, | 0:53:15 | 0:53:18 | |

made from playing at weddings and funerals. | 0:53:18 | 0:53:21 | |

At the end of each frantic week, Bach unveiled his latest cantata. | 0:53:30 | 0:53:34 | |

What the Leipzig congregation made of these towering works, | 0:53:35 | 0:53:39 | |

frustratingly, we simply don't know. | 0:53:39 | 0:53:41 | |

All we do know is that plenty of people would have heard them. | 0:53:42 | 0:53:45 | |

Leipzig was known as "the city of churches". | 0:53:45 | 0:53:49 | |

It's been estimated that on a normal Sunday, | 0:53:49 | 0:53:52 | |

of a population of 30,000, 9,000 parishioners | 0:53:52 | 0:53:56 | |

and members of society were crammed into these two churches. | 0:53:56 | 0:54:01 | |

The Thomaskirche, the Nikolaikirche, | 0:54:01 | 0:54:03 | |

and bulging from the seams of the other churches in the town. | 0:54:03 | 0:54:06 | |

Thus, every week, Bach had an audience | 0:54:08 | 0:54:11 | |

10 or a dozen times bigger than in any opera house. | 0:54:11 | 0:54:14 | |

Unfortunately, people at the main churches tended to behave | 0:54:14 | 0:54:17 | |

as if they were in an opera house, much to the fury of the clergy. | 0:54:17 | 0:54:21 | |

The preachers often think | 0:54:22 | 0:54:23 | |

they don't listen carefully to the sermons, that's for sure. | 0:54:23 | 0:54:26 | |

You get all kinds of complaints about people flirting in church, | 0:54:26 | 0:54:30 | |

people sleeping in church, people throwing paper aeroplanes in church. | 0:54:30 | 0:54:34 | |

-Yes. -Taking snuff in church. -Dogs coming into church. -Absolutely. | 0:54:34 | 0:54:39 | |

And some churches employed special dog whippers to get the dogs out. | 0:54:39 | 0:54:42 | |

-Really? -And earlier on you had complaints about people | 0:54:42 | 0:54:45 | |

taking pigs through church because it's the quickest way | 0:54:45 | 0:54:48 | |

from where the pig was to market, and so on. | 0:54:48 | 0:54:50 | |

So I think our sense of proper behaviour in a church is different. | 0:54:50 | 0:54:55 | |

So, there must have been a huge amount of noise, | 0:54:55 | 0:54:58 | |

and one of the problems - that's one of the few things | 0:54:58 | 0:55:01 | |

we really do know - is that people drifted in and out, | 0:55:01 | 0:55:05 | |

before the sermon, after the sermon, during the music. | 0:55:05 | 0:55:08 | |

It must have been chaos. | 0:55:08 | 0:55:10 | |

Everything was very, very stratified here socially, | 0:55:10 | 0:55:13 | |

so the ladies were seated down here, below, | 0:55:13 | 0:55:17 | |

the men were in the two galleries, both sides, | 0:55:17 | 0:55:20 | |

and the hoi polloi were at the back with the riff raff. | 0:55:20 | 0:55:24 | |

And the music, of course, came from the back of the Church, | 0:55:26 | 0:55:29 | |

up in the organ gallery. | 0:55:29 | 0:55:31 | |

And it was raining down on the congregation, | 0:55:31 | 0:55:33 | |

but exactly at the moment where the ladies made their grand entrance. | 0:55:33 | 0:55:38 | |

And given the fact this is Germany, | 0:55:38 | 0:55:41 | |

there was a huge amount of social greetings... | 0:55:41 | 0:55:44 | |

Wie geht es Ihnen, gnaedige Frau? That sort of thing. | 0:55:44 | 0:55:47 | |

..while the ladies took their seats and then gazed up | 0:55:47 | 0:55:50 | |

adoringly at the preacher about to give his sermon. | 0:55:50 | 0:55:53 | |

And the hubbub during Bach's music must have been excruciating. | 0:55:54 | 0:55:58 | |

Poor man. | 0:55:58 | 0:55:59 | |

This, then, is the congregation who first heard the masterpiece | 0:56:00 | 0:56:03 | |

Bach presented at the Nikolaikirche on Good Friday 1724. | 0:56:03 | 0:56:07 | |

It was his first passion oratorio, | 0:56:07 | 0:56:10 | |

the central jewel of his necklace of cantatas, a musical | 0:56:10 | 0:56:13 | |

retelling of the story of Jesus' arrest, trial and crucifixion. | 0:56:13 | 0:56:17 | |

There had been passions before, but nothing so radical, | 0:56:17 | 0:56:21 | |

so complex or as ambitious as Bach's John Passion. | 0:56:21 | 0:56:25 | |

He ingeniously blends orchestral and choral writing | 0:56:25 | 0:56:29 | |

into a thrilling amalgam of storytelling, meditation and drama. | 0:56:29 | 0:56:33 | |

Can I just have the cello and bass, please? | 0:56:33 | 0:56:36 | |

Violas start. Bar one. | 0:56:36 | 0:56:38 | |

That's OK. Now, can we just add the violins, please? | 0:56:42 | 0:56:46 | |

Good, that's it. Right, thank you. | 0:56:52 | 0:56:55 | |

And just flutes and oboes, please. And one... | 0:56:55 | 0:56:59 | |

It's like nails being driven into bare flesh. | 0:57:10 | 0:57:13 | |

That's it. That's it. | 0:57:17 | 0:57:18 | |

In this opening chorus, he does something which none of | 0:57:18 | 0:57:21 | |

the other people had done, which is to set up a huge dynamic tension | 0:57:21 | 0:57:27 | |

between this turbulence in the orchestra going on | 0:57:27 | 0:57:31 | |

and this tremendous acclamation of Christ in majesty. | 0:57:31 | 0:57:35 | |

Bach was not trying to write an opera. | 0:59:20 | 0:59:22 | |

Bach's purpose was to draw the listener in. To recreate | 0:59:22 | 0:59:26 | |

in front of their ears and eyes the drama of Christ's crucifixion. | 0:59:26 | 0:59:32 | |

And his St John Passion is an extraordinary amalgam of theology | 0:59:32 | 0:59:37 | |

and music, religion and politics, drama | 0:59:37 | 0:59:41 | |

and wonderful presentation of storytelling. | 0:59:41 | 0:59:44 | |

So we sense the tension that is already in St John's gospel, | 0:59:44 | 0:59:48 | |

that between the light and darkness, between sin and good work | 0:59:48 | 0:59:54 | |

and faith and doubt. | 0:59:54 | 0:59:57 | |

John is particularly remarkable | 1:00:16 | 1:00:18 | |

because you could say that in his account of the Passion, | 1:00:18 | 1:00:22 | |

everybody else suffers and is perplexed and agonised, | 1:00:22 | 1:00:26 | |

and Jesus is utterly stable. | 1:00:26 | 1:00:30 | |

I mean, he's not suffering, he's not under things, | 1:00:30 | 1:00:32 | |

he sort of stands there over and above them. | 1:00:32 | 1:00:35 | |

-Zen-like. -He's extremely enigmatic. | 1:00:35 | 1:00:38 | |

I mean, in the middle you have Christ's sacrifice, | 1:01:14 | 1:01:18 | |

in which he takes upon himself human sin and gives people back grace. | 1:01:18 | 1:01:23 | |

That's in the middle. | 1:01:23 | 1:01:25 | |

And then, on one side of that, there are the individuals in the text, | 1:01:25 | 1:01:30 | |

particularly Pilate. | 1:01:30 | 1:01:32 | |

Then, on either side of that, there is community, | 1:01:32 | 1:01:37 | |

-there's the mad community... -The mob. -..of the chorus. The mob. | 1:01:37 | 1:01:40 | |

Hysterical, paranoid, and utterly deranged, really. | 1:01:40 | 1:01:45 | |

On the other side is the present community, which is in order | 1:01:45 | 1:01:51 | |

and sings these sculptural, monumental chorales. | 1:01:51 | 1:01:55 | |

So there you have... | 1:01:55 | 1:01:56 | |

As you say, he ticks all the boxes, he includes the whole thing, | 1:01:56 | 1:02:00 | |

the whole human thing, individual, social. | 1:02:00 | 1:02:04 | |

-And it's a reflection of Lutheran... ordered society? -It is. | 1:02:04 | 1:02:09 | |

Today the St John Passion is accepted as a masterpiece, | 1:02:56 | 1:02:59 | |

but at its first performance it didn't please the Leipzig clergy, | 1:02:59 | 1:03:03 | |

ever suspicious | 1:03:03 | 1:03:05 | |

and alert to the danger of music stealing their thunder. | 1:03:05 | 1:03:08 | |

Bach was forced to revise it radically over the next year, | 1:03:08 | 1:03:12 | |

and only towards the end of his life was it once again performed | 1:03:12 | 1:03:15 | |

in a version close to its original. | 1:03:15 | 1:03:18 | |

Without so much as a break, Bach began another round of cantatas. | 1:03:38 | 1:03:41 | |

This time the cycle was based on iconic chorales, | 1:03:41 | 1:03:45 | |

and Bach had to write a new work each week. | 1:03:45 | 1:03:48 | |

The cycle is breathtaking in the variety of its moods, | 1:03:48 | 1:03:51 | |

intensely serious at one moment, cheeky at the next. | 1:03:51 | 1:03:54 | |

Measure him against any of his contemporaries, | 1:04:56 | 1:04:59 | |

and there's one thing that makes Bach stick out from all the rest. | 1:04:59 | 1:05:02 | |

He didn't write an opera, not a single opera. | 1:05:02 | 1:05:06 | |

And yet, at the time, opera was really the gold currency, | 1:05:07 | 1:05:12 | |

it was the thing that established careers. | 1:05:12 | 1:05:15 | |

It brought with it fame, it brought with it success, | 1:05:15 | 1:05:19 | |

it brought with it a lot of money, and Bach would have none of that. | 1:05:19 | 1:05:23 | |

In fact, he talked rather disparagingly of those | 1:05:23 | 1:05:26 | |

little ditties that you could hear at the Dresden Opera. | 1:05:26 | 1:05:29 | |

And yet his music is intrinsically as dramatic, if not more dramatic, | 1:05:31 | 1:05:36 | |

than that of any of the opera composers of the day. | 1:05:36 | 1:05:40 | |

Vivaldi, Scarlatti, Telemann, none could match Bach in this respect. | 1:05:40 | 1:05:45 | |

Only Handel came close. | 1:05:45 | 1:05:46 | |

Everything Bach had learned up to now, dramatic scene-setting | 1:05:47 | 1:05:51 | |

to underpin the Gospel narration, | 1:05:51 | 1:05:53 | |

and subtle musical power to convey contrition and remorse, | 1:05:53 | 1:05:56 | |

was poured into his St Matthew Passion, | 1:05:56 | 1:05:58 | |

first performed at the Thomaskirche Leipzig on Good Friday 1727. | 1:05:58 | 1:06:03 | |

The St Matthew Passion is even more atmospheric than the St John. | 1:06:28 | 1:06:32 | |

Lasting around two-and-a-half hours, it's even more monumental in scale, | 1:06:32 | 1:06:36 | |

with a double choir and a double orchestra. | 1:06:36 | 1:06:39 | |

He speaks with the voice of someone | 1:06:51 | 1:06:54 | |

whose belief is absolutely rock solid. | 1:06:54 | 1:06:56 | |

Goes right to the roots of his being. | 1:06:56 | 1:06:59 | |

He believes every word of this, it is true, that it is completely true. | 1:06:59 | 1:07:04 | |

And...there's a solidity, a firmness to what comes through | 1:07:04 | 1:07:09 | |

in the Passions that I have seen very rarely anywhere else. | 1:07:09 | 1:07:14 | |

You wonder, well, where is there room for Bach's own voice? | 1:07:47 | 1:07:51 | |

It's difficult to answer, but I feel there are moments, | 1:07:51 | 1:07:54 | |

chinks in the drama, where you feel that Bach himself | 1:07:54 | 1:07:58 | |

is very much present and very much making the decisions. | 1:07:58 | 1:08:01 | |

So you've got a, er, crotchet, to turn round completely, | 1:08:09 | 1:08:13 | |

180 degrees, from being an absolutely foulmouthed mob | 1:08:13 | 1:08:16 | |

into being contrite and responsible and tender. | 1:08:16 | 1:08:20 | |

And bewildered - who's hit you? | 1:08:20 | 1:08:22 | |

We don't understand. Go. | 1:08:22 | 1:08:25 | |

The choir have to switch into being the community, the believers. | 1:08:40 | 1:08:46 | |

And it's in that moment that I feel Bach is saying, | 1:08:48 | 1:08:51 | |

"This suffering is unbearable. We have to stop it. | 1:08:51 | 1:08:55 | |

"We have to show our sense of moral outrage." | 1:08:55 | 1:08:59 | |

The emotional centre of the Matthew Passion is Erbarme Dich, | 1:09:13 | 1:09:17 | |

Peter's plea for forgiveness, having denied his Christ. | 1:09:17 | 1:09:22 | |

In comes the violin, announcing, "Erbarme dich," | 1:09:22 | 1:09:26 | |

and the violin with no words at all can convey, in a way that | 1:09:26 | 1:09:31 | |

the human voice could not convey, this concentration of lamentation, | 1:09:31 | 1:09:37 | |

of grief, of contrition, of utter abject horror, in a way, | 1:09:37 | 1:09:42 | |

and yet taking on to a spiritual level, | 1:09:42 | 1:09:46 | |

because the voice line of the violin becomes an agency of... | 1:09:46 | 1:09:52 | |

of compassion and forgiveness, and that's before the singer's sung a note. | 1:09:52 | 1:09:56 | |

Three years after the St Matthew Passion, | 1:12:13 | 1:12:15 | |

Bach's relationship with his masters began to fall apart. | 1:12:15 | 1:12:19 | |

In 1730, he wrote what he called an "Entwurf," | 1:12:19 | 1:12:22 | |

a memorandum to the Leipzig council, | 1:12:22 | 1:12:24 | |

complaining bitterly that he could no longer operate. | 1:12:24 | 1:12:28 | |

He hadn't sufficient musicians, | 1:12:28 | 1:12:29 | |

and too few of quality to perform his work. | 1:12:29 | 1:12:33 | |

Several months later, Bach took up his pen again. | 1:12:33 | 1:12:36 | |

And this is the most poignant document of all for me. | 1:12:37 | 1:12:41 | |

It's the only truly personal letter we have of Bach's, | 1:12:41 | 1:12:45 | |

in which he's writing to his old pal, Georg Erdmann. | 1:12:45 | 1:12:50 | |

He was the guy that Bach walked from Ohrdruf to Lueneburg with | 1:12:50 | 1:12:55 | |

when they were both in their early teens. | 1:12:55 | 1:12:58 | |

And Bach is just pouring out all his frustration about why | 1:12:58 | 1:13:02 | |

the council had not responded to this Entwurf, | 1:13:02 | 1:13:06 | |

this statement of his intentions. | 1:13:06 | 1:13:09 | |

And Bach tells Erdmann, | 1:13:09 | 1:13:12 | |

"My life is full of hindrance and vexation and I see no future for myself and my family here." | 1:13:12 | 1:13:19 | |

One of the features that you might expect to see in this | 1:13:19 | 1:13:23 | |

inflexible persona, if you like, is that he would never be guilty. | 1:13:23 | 1:13:28 | |

No matter what happened, it's always somebody else's fault. | 1:13:28 | 1:13:31 | |

-Does that ring? -Yes, it does. Because he's never to blame. | 1:13:31 | 1:13:36 | |

He always has a reason. And his motto... | 1:13:36 | 1:13:40 | |

I don't know whether it's his motto but something that's like a mantra | 1:13:40 | 1:13:43 | |

that comes up and up and again, | 1:13:43 | 1:13:44 | |

is that "My life is lived always with fixation and hindrance." | 1:13:44 | 1:13:49 | |

I have brought you something here, which is a textbook definition, | 1:13:49 | 1:13:54 | |

and this is paranoid personality disorder, | 1:13:54 | 1:13:57 | |

and these are the characteristics. | 1:13:57 | 1:13:59 | |

"Pervasive suspicion of others, distrusting their motives. | 1:13:59 | 1:14:03 | |

"Others seen as deliberately demeaning or threatening, | 1:14:03 | 1:14:07 | |

"constantly expect to be harmed or exploited, | 1:14:07 | 1:14:09 | |

"very sensitive to perceived slights, | 1:14:09 | 1:14:12 | |

"fear and avoidance of anything that could make them feel or seem weak." | 1:14:12 | 1:14:17 | |

That's a perfect description. | 1:14:17 | 1:14:19 | |

The one thing that we do know is that there is an association with | 1:14:21 | 1:14:26 | |

bullying and abuse in childhood. | 1:14:26 | 1:14:28 | |

Thanks to the bone-headedness of the city fathers | 1:14:30 | 1:14:33 | |

and the obvious flaws in Bach's own character, | 1:14:33 | 1:14:36 | |

his output of religious music now began to dwindle away. | 1:14:36 | 1:14:39 | |

St Thomas's Church didn't deserve those cantatas. | 1:14:40 | 1:14:44 | |

Nobody deserved those cantatas, but least of all St Thomas's Church. | 1:14:44 | 1:14:47 | |

That's the striking thing about a great artist, | 1:14:47 | 1:14:49 | |

is they deliver absurdly over contract - | 1:14:49 | 1:14:53 | |

heartbreakingly over contract - and that is the thing that | 1:14:53 | 1:14:56 | |

I think is most impressive and very deeply moving about him. | 1:14:56 | 1:15:00 | |

There he is, worrying about his children, | 1:15:00 | 1:15:02 | |

who are popping off one after the other, | 1:15:02 | 1:15:05 | |

worrying about their education, | 1:15:05 | 1:15:06 | |

trying to keep the town councillors less irritated, | 1:15:06 | 1:15:10 | |

and so on and so forth, and at the same time, he just delivered... | 1:15:10 | 1:15:15 | |

this work that, 250, 260 years later, is supreme in the canon. | 1:15:15 | 1:15:19 | |

Bach now gravitated towards the other main centre of music-making | 1:15:22 | 1:15:25 | |

in Leipzig, the thriving coffeehouse scene. | 1:15:25 | 1:15:29 | |

Here was a different audience, | 1:15:29 | 1:15:30 | |

a more relaxed ambience in which to make music with better musicians | 1:15:30 | 1:15:34 | |

from the university, eager to learn from the master. | 1:15:34 | 1:15:37 | |

But Bach didn't completely give up on sacred music. | 1:15:41 | 1:15:44 | |

Indeed, his new secular style found its way into religious pieces | 1:15:44 | 1:15:48 | |

of unbuttoned high spirits. | 1:15:48 | 1:15:50 | |

Throughout his life, | 1:16:26 | 1:16:27 | |

Bach had much more than his fair share of heartbreak. | 1:16:27 | 1:16:31 | |

That direct experience of personal grief comes over in his music, | 1:16:31 | 1:16:34 | |

but never in a saccharine or morbid way, | 1:16:34 | 1:16:37 | |

but as consoling, soothing, uplifting. | 1:16:37 | 1:16:41 | |

In many ways, you can imagine he's creating a lullaby for himself, | 1:16:41 | 1:16:44 | |

which, again, becomes a lullaby for all of us. | 1:16:44 | 1:16:47 | |

A profound lullaby which comforts him and through him, comforts us. | 1:16:47 | 1:16:53 | |

The thing that to me is so touching | 1:18:19 | 1:18:22 | |

and powerful in the expression of the music is the way that | 1:18:22 | 1:18:25 | |

Bach seems to focus all that distress | 1:18:25 | 1:18:29 | |

and private grief in his own life, | 1:18:29 | 1:18:32 | |

the loss of parents, the loss of children, the loss of a wife, | 1:18:32 | 1:18:35 | |

always the difficulties that he was experiencing, | 1:18:35 | 1:18:39 | |

and yet, the music that comes out of it is so ineffably consoling | 1:18:39 | 1:18:43 | |

-and...touching. -And nowadays, we look at the texts, | 1:18:43 | 1:18:49 | |

and with this constant longing for death, | 1:18:49 | 1:18:53 | |

this anticipation with joy of one's final demise, it seems bizarre to us | 1:18:53 | 1:18:59 | |

and yet it's with, as you say, | 1:18:59 | 1:19:04 | |

Bach's private grief, it was commonplace. | 1:19:04 | 1:19:06 | |

-EVERYBODY'S private grief. -Absolutely. | 1:19:06 | 1:19:08 | |

Everybody was losing their families, their babies, their wives. | 1:19:08 | 1:19:12 | |

And, you know, this is surely | 1:19:12 | 1:19:14 | |

the prime purpose of religion at that time, | 1:19:14 | 1:19:18 | |

was to give a consolation in the face of this baffling reality. | 1:19:18 | 1:19:21 | |

With his disagreements with the council dragging on and on, | 1:19:22 | 1:19:26 | |

Bach now had a new power struggle. | 1:19:26 | 1:19:28 | |

This time, with the headmaster of the Thomas School who was | 1:19:28 | 1:19:31 | |

bitterly opposed to all the emphasis on music in school. | 1:19:31 | 1:19:34 | |

In Bach's desire to put an end to his woes in Leipzig, | 1:19:36 | 1:19:39 | |

we find the origins of one late religious masterpiece, | 1:19:39 | 1:19:42 | |

the B minor Mass. | 1:19:42 | 1:19:44 | |

Just try and think how different this is from Messiah. | 1:19:44 | 1:19:47 | |

Messiah, you've got the angels wafting in on a cloud | 1:19:47 | 1:19:50 | |

and they come in and they sing and then disappear, all very gently. | 1:19:50 | 1:19:53 | |

Here, it's a stomp. It's much more kind of Bruegel than Botticelli, | 1:19:53 | 1:19:57 | |

it's not wiffy-waffy at all. OK, off we go. Yep? | 1:19:57 | 1:20:00 | |

Bach was angling for a new job, | 1:20:09 | 1:20:11 | |

or at the very least an honorary title, | 1:20:11 | 1:20:13 | |

at the court in Dresden, which was Catholic, | 1:20:13 | 1:20:16 | |

so despite his unwavering commitment to Lutheranism, | 1:20:16 | 1:20:19 | |

Bach, ever practical, saw there was an opportunity for composing | 1:20:19 | 1:20:22 | |

a Latin Mass on a grand scale. | 1:20:22 | 1:20:24 | |

Bach didn't get his hoped-for move to Dresden, | 1:21:26 | 1:21:29 | |

although he did get the honorary title, | 1:21:29 | 1:21:31 | |

and for the next 15 years, we lose all trace of the B minor Mass. | 1:21:31 | 1:21:35 | |

And then suddenly, we have a Missa Tota, | 1:21:38 | 1:21:42 | |

a complete Catholic Mass with the magnificent Credo and the wonderful | 1:21:42 | 1:21:47 | |

Agnus Dei and the touching way it ends with the Dona Nobis Pacem. | 1:21:47 | 1:21:52 | |

This was Bach's compendium of all the style | 1:21:52 | 1:21:56 | |

since he was a young composer up to the most recent music | 1:21:56 | 1:22:00 | |

that he composed. It was his version of Ars Perfecta, of art perfected. | 1:22:00 | 1:22:07 | |