The Secret of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony

Similar Content

Browse content similar to The Secret of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

THEY PLAY OPENING NOTES OF BEETHOVEN'S FIFTH SYMPHONY | 0:00:02 | 0:00:05 | |

Ludwig van Beethoven's Fifth Symphony may be | 0:00:06 | 0:00:09 | |

one of the greatest pieces of music ever written. | 0:00:09 | 0:00:12 | |

It's certainly one of the most famous. | 0:00:12 | 0:00:14 | |

And those first four notes, once heard, are never forgotten. | 0:00:19 | 0:00:23 | |

The traditional wisdom has been that in the Fifth, | 0:00:27 | 0:00:29 | |

Beethoven is railing against fate and his increasing deafness. | 0:00:29 | 0:00:33 | |

But conductor John Eliot Gardiner believes | 0:00:37 | 0:00:40 | |

that it contains a hidden, radical message. | 0:00:40 | 0:00:42 | |

Expressing the composer's sympathy with | 0:00:42 | 0:00:45 | |

the ideals of the French Revolution. | 0:00:45 | 0:00:48 | |

Liberty, equality and brotherhood. | 0:00:48 | 0:00:51 | |

It's not just a matter of his expressing his inner turmoil, | 0:00:52 | 0:00:56 | |

it's also him nailing his colours to the political mast | 0:00:56 | 0:01:00 | |

of the French Revolution. | 0:01:00 | 0:01:02 | |

"I believe in the rights of man, | 0:01:07 | 0:01:09 | |

"I believe in the brotherhood of all men | 0:01:09 | 0:01:11 | |

"and I believe in political freedom." | 0:01:11 | 0:01:13 | |

I'm going to look at the evidence | 0:01:17 | 0:01:19 | |

for this revolutionary interpretation | 0:01:19 | 0:01:21 | |

of the Fifth Symphony. | 0:01:21 | 0:01:23 | |

I'll visit France, where in 1789, | 0:01:23 | 0:01:26 | |

the world order was turned upside down. | 0:01:26 | 0:01:28 | |

I'll be exploring Bonn, where Beethoven grew up | 0:01:30 | 0:01:33 | |

and was exposed to radical ideas. | 0:01:33 | 0:01:35 | |

And I'll travel to Vienna, | 0:01:37 | 0:01:39 | |

the imperial capital that was Beethoven's home | 0:01:39 | 0:01:42 | |

as the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars convulsed Europe. | 0:01:42 | 0:01:45 | |

We'll see how these extraordinary events affected Beethoven, | 0:01:47 | 0:01:51 | |

both as a man and a musician, and how his passion for the ideals | 0:01:51 | 0:01:55 | |

of freedom and brotherhood fuelled the Fifth Symphony. | 0:01:55 | 0:02:01 | |

With my Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique, | 0:02:04 | 0:02:08 | |

we're going to perform Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, | 0:02:08 | 0:02:12 | |

and we're going to try to incorporate the emotional turmoil | 0:02:12 | 0:02:18 | |

and passion and the republican political fervour | 0:02:18 | 0:02:23 | |

which informs this great symphony. | 0:02:23 | 0:02:25 | |

So, are you all sitting comfortably? | 0:02:31 | 0:02:35 | |

You're not meant to be. | 0:02:35 | 0:02:36 | |

Ludwig van Beethoven wrote his Fifth Symphony here in Vienna, | 0:02:56 | 0:02:59 | |

the Austrian capital, | 0:02:59 | 0:03:01 | |

where the composer lived and worked for most of his life. | 0:03:01 | 0:03:04 | |

It's become a timeless musical monument, but it was directly shaped | 0:03:06 | 0:03:11 | |

by the troubled times in which Beethoven lived. | 0:03:11 | 0:03:14 | |

And this may have been underestimated | 0:03:14 | 0:03:16 | |

in the centuries since it was written. | 0:03:16 | 0:03:19 | |

There's no better place to start an exploration of how and why | 0:03:19 | 0:03:22 | |

this happened than the place where the symphony was heard | 0:03:22 | 0:03:25 | |

for the very first time in December 1808. | 0:03:25 | 0:03:29 | |

I'm here at the Theater an der Wien, | 0:03:34 | 0:03:36 | |

a very important place for Beethoven, | 0:03:36 | 0:03:38 | |

and it's connected with a number of his great works. | 0:03:38 | 0:03:41 | |

But it was in this very theatre that the Fifth Symphony had its premiere. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:45 | |

Beethoven was 38 and at the height of his creative powers. | 0:03:49 | 0:03:53 | |

The premiere of the Fifth was scheduled towards the end | 0:03:53 | 0:03:56 | |

of a benefit concert for himself, | 0:03:56 | 0:03:59 | |

a packed recital of his great works. | 0:03:59 | 0:04:02 | |

Beethoven was the first successful freelance composer, | 0:04:02 | 0:04:06 | |

not employed by the court, so he needed the money more than most. | 0:04:06 | 0:04:10 | |

It turned out to be a very interesting evening | 0:04:11 | 0:04:14 | |

How does it go, this huge event, the Beethoven programme? | 0:04:17 | 0:04:20 | |

It's a disaster. | 0:04:20 | 0:04:22 | |

It's a complete disaster, unfortunately. It's too long. | 0:04:22 | 0:04:25 | |

Imagine, it takes four hours, | 0:04:25 | 0:04:27 | |

so it lasts until 10.30 in the night. | 0:04:27 | 0:04:30 | |

Unfortunately, the musicians and Beethoven had a row, | 0:04:30 | 0:04:33 | |

so he didn't actually talk to the orchestra himself, | 0:04:33 | 0:04:35 | |

he only talked to the conductors. | 0:04:35 | 0:04:37 | |

And the conductors then talked to the orchestra. | 0:04:37 | 0:04:39 | |

-LAUGHING: Right! -It's a nightmare. | 0:04:39 | 0:04:41 | |

-What had they had a row about? -About the rehearsal conditions | 0:04:41 | 0:04:45 | |

and about Beethoven being very late on delivering the score. | 0:04:45 | 0:04:48 | |

Apparently, there were also mistakes, because they didn't have | 0:04:48 | 0:04:51 | |

enough time to rehearse, and at some point, Beethoven actually | 0:04:51 | 0:04:54 | |

stopped the concert and started again from the beginning. | 0:04:54 | 0:04:57 | |

IAN LAUGHS Was it full? | 0:04:57 | 0:04:59 | |

-No. -No? -Half-full only, unfortunately. | 0:04:59 | 0:05:02 | |

No, unfortunately, the same night there was | 0:05:02 | 0:05:04 | |

another concert going on, for widows and orphans. | 0:05:04 | 0:05:07 | |

A benefit concert, similarly as this was | 0:05:07 | 0:05:10 | |

-a benefit concert for Beethoven personally. -For himself. | 0:05:10 | 0:05:13 | |

Exactly. So now, unfortunately, it was only half-filled. Tough luck. | 0:05:13 | 0:05:18 | |

He didn't earn as much money as he would have hoped. | 0:05:18 | 0:05:21 | |

Beethoven has become the classic example of | 0:05:21 | 0:05:23 | |

the intense, tortured artist. | 0:05:23 | 0:05:26 | |

But he was capable of great kindness as well as terrible tantrums, | 0:05:26 | 0:05:29 | |

compassion as well as passion, | 0:05:29 | 0:05:31 | |

the composer of deeply sensitive pieces | 0:05:31 | 0:05:34 | |

as well as what became known as heaven-storming works. | 0:05:34 | 0:05:37 | |

As we'll see, the Fifth Symphony's four movements | 0:05:39 | 0:05:41 | |

display all these aspects of its creator. | 0:05:41 | 0:05:45 | |

But the symphony's opening was not a soothing composition | 0:05:45 | 0:05:48 | |

that the theatre audience could sit back, relax and enjoy. | 0:05:48 | 0:05:53 | |

It was meant to jolt them out of their seats. | 0:05:53 | 0:05:55 | |

The Fifth - especially the first four notes - has become | 0:05:56 | 0:05:59 | |

so well-known that it's difficult to recreate the shock | 0:05:59 | 0:06:02 | |

and disorientation that Beethoven intended. | 0:06:02 | 0:06:06 | |

Difficult, but not impossible. | 0:06:06 | 0:06:08 | |

Over the centuries, Beethoven's masterpiece has been performed | 0:06:10 | 0:06:13 | |

in ways that the bad-tempered maestro might well have hated. | 0:06:13 | 0:06:18 | |

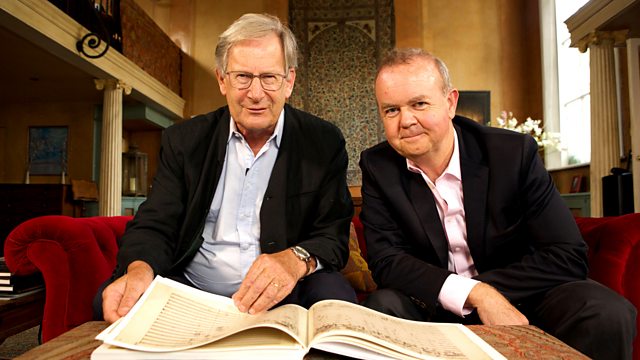

But for over 25 years, conductor Sir John Eliot Gardiner and his | 0:06:18 | 0:06:21 | |

Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique have been on a mission | 0:06:21 | 0:06:26 | |

to play Beethoven's symphonies in just the way he intended. | 0:06:26 | 0:06:30 | |

Here at St John's Smith Square in London, they have recorded | 0:06:30 | 0:06:33 | |

a performance of the Fifth Symphony especially for us, | 0:06:33 | 0:06:36 | |

with all the pace and the ferocity | 0:06:36 | 0:06:39 | |

that the audience at the premiere would have experienced. | 0:06:39 | 0:06:42 | |

Right, here we go. | 0:06:42 | 0:06:43 | |

If there is any single piece of Beethoven's | 0:07:03 | 0:07:05 | |

that really, really sort of sets one's pulse racing, | 0:07:05 | 0:07:08 | |

it's the Fifth Symphony. | 0:07:08 | 0:07:10 | |

Because there is something completely implacable about it. | 0:07:26 | 0:07:29 | |

It's so full-on, and it leaves you breathless, | 0:07:29 | 0:07:32 | |

because there is this searing energy right from the off. | 0:07:32 | 0:07:36 | |

And then once he is in his full stride, | 0:07:37 | 0:07:39 | |

he just never lets up and it's inexorable. | 0:07:39 | 0:07:41 | |

I think the thing about tempo is | 0:08:03 | 0:08:05 | |

that it has to be done with total conviction. | 0:08:05 | 0:08:08 | |

And if you feel, as I do, that Beethoven is impatient | 0:08:10 | 0:08:15 | |

to get his ideas over, then it's going to come over fast. | 0:08:15 | 0:08:18 | |

John Eliot plays the Fifth Symphony at 108 beats per minute - | 0:08:21 | 0:08:25 | |

the tempo Beethoven himself decided for it. | 0:08:25 | 0:08:29 | |

The composer famously started losing his hearing when he was | 0:08:29 | 0:08:32 | |

in his twenties, and specified this tempo | 0:08:32 | 0:08:36 | |

years after composing the Fifth, when he had become entirely deaf. | 0:08:36 | 0:08:39 | |

108bpm is SO fast that many conductors and performers | 0:08:39 | 0:08:44 | |

have ignored this marking. | 0:08:44 | 0:08:46 | |

So this metronome is set at...? | 0:08:47 | 0:08:49 | |

108bpm. | 0:08:49 | 0:08:51 | |

-Right. -And this is a new invention. | 0:08:51 | 0:08:54 | |

Beethoven was excited, and he would be, bound to be, | 0:08:54 | 0:08:57 | |

because if he had no means of conveying to performers... | 0:08:57 | 0:09:00 | |

Because he wasn't a conductor and he was deaf | 0:09:00 | 0:09:03 | |

-and he couldn't convey his ideas... -Yeah, he could tell them | 0:09:03 | 0:09:05 | |

-how fast how fast or slow to go. -He could tell them. | 0:09:05 | 0:09:08 | |

But...sitting here and listening to that is one thing. | 0:09:08 | 0:09:11 | |

Actually standing in front of an orchestra | 0:09:11 | 0:09:14 | |

and playing the music is quite different. | 0:09:14 | 0:09:16 | |

But that's why you play it so fast, isn't it? | 0:09:16 | 0:09:19 | |

I do, I think it's a good guideline, | 0:09:19 | 0:09:21 | |

and I may even go a bit quicker than that, depends... | 0:09:21 | 0:09:24 | |

Well, it depends on the set-up. It depends on the hall. | 0:09:24 | 0:09:27 | |

In the Albert Hall, you know, you don't want to go | 0:09:27 | 0:09:30 | |

at such a lick that the music | 0:09:30 | 0:09:32 | |

doesn't have a chance to register with an audience. | 0:09:32 | 0:09:35 | |

Whereas if you're doing it in a small studio, | 0:09:35 | 0:09:37 | |

you can get closer to Beethoven. | 0:09:37 | 0:09:39 | |

Over the centuries, many conductors have played the Fifth | 0:09:47 | 0:09:50 | |

at much slower tempi. | 0:09:50 | 0:09:52 | |

All through the early part of the 20th century, | 0:09:52 | 0:09:55 | |

the great maestri of the day tended to expand it | 0:09:55 | 0:09:58 | |

and be very self-indulgent, and to pull around the tempo. | 0:09:58 | 0:10:02 | |

OPENING NOTES OF FIFTH SYMPHONY, MUCH SLOWER | 0:10:02 | 0:10:05 | |

One recording even slowed it down to close to 74bpm. | 0:10:05 | 0:10:08 | |

OK, this is now at 74, how does that strike you? | 0:10:11 | 0:10:15 | |

Bit of a bore, bit of a snore, actually. | 0:10:15 | 0:10:18 | |

How can one...? | 0:10:18 | 0:10:19 | |

How can you galvanise an orchestra...? | 0:10:19 | 0:10:21 | |

# Da-da-da-dee... | 0:10:21 | 0:10:23 | |

"Ugh..." | 0:10:23 | 0:10:24 | |

# Da-da-da-dee... # | 0:10:24 | 0:10:26 | |

I mean, they'd absolutely fall asleep in their chairs. | 0:10:26 | 0:10:30 | |

METRONOME TICKS | 0:10:30 | 0:10:32 | |

-It's having that effect now! -Well... | 0:10:32 | 0:10:34 | |

And he uses that kind of motto or icon, as it were, | 0:10:42 | 0:10:47 | |

the "ba-ba-ba-bam", | 0:10:47 | 0:10:48 | |

those four notes which... | 0:10:48 | 0:10:51 | |

Given in that rhythm as a constant right the way through the symphony. | 0:10:51 | 0:10:57 | |

So, what message could Beethoven be trying to convey | 0:11:00 | 0:11:04 | |

with a furiously fast performance of his four-note motif? | 0:11:04 | 0:11:07 | |

By the time he composed the Fifth, Beethoven had accepted | 0:11:15 | 0:11:18 | |

that his deafness was incurable. | 0:11:18 | 0:11:20 | |

The terrible realisation came during a stroll | 0:11:20 | 0:11:23 | |

with a friend, Ferdinand Ries. | 0:11:23 | 0:11:24 | |

Ries says "Master, listen to that shepherd blowing on his pipe." | 0:11:26 | 0:11:31 | |

And Beethoven realises he can see the chap playing the pipe | 0:11:31 | 0:11:33 | |

but he can't hear him, | 0:11:33 | 0:11:35 | |

and that's the first time that we know of | 0:11:35 | 0:11:38 | |

that it's not just someone talking that he can't hear, | 0:11:38 | 0:11:41 | |

but it's music - and what else is he but a musician? | 0:11:41 | 0:11:44 | |

This is why many have believed that the four notes | 0:11:49 | 0:11:51 | |

are the composer railing against his deafness. | 0:11:51 | 0:11:54 | |

But not everyone. | 0:11:54 | 0:11:56 | |

John Eliot thinks differently. | 0:11:57 | 0:12:00 | |

So what do YOU think Beethoven was saying in the Fifth Symphony? | 0:12:00 | 0:12:03 | |

Well, I think he's really trying to convey | 0:12:05 | 0:12:09 | |

his deeply-held political beliefs at the time. | 0:12:09 | 0:12:13 | |

I mean, Beethoven's political beliefs went up and down, | 0:12:13 | 0:12:17 | |

but at the particular time he was writing the symphony, | 0:12:17 | 0:12:20 | |

in the early 1800s, | 0:12:20 | 0:12:21 | |

he was completely under the spell of the French Revolution | 0:12:21 | 0:12:25 | |

and even contemplated moving from Bonn and Vienna to Paris. | 0:12:25 | 0:12:31 | |

And it always amuses me, | 0:12:31 | 0:12:32 | |

the thought of Beethoven prowling around in Paris | 0:12:32 | 0:12:35 | |

and not speaking a word of French - or very little - | 0:12:35 | 0:12:37 | |

and you know, how would musical history | 0:12:37 | 0:12:39 | |

have developed if he had become a Frenchman? | 0:12:39 | 0:12:42 | |

-It would have been... -Yes. -..a bit different. | 0:12:42 | 0:12:44 | |

Could the revolution provide the secret to the Fifth Symphony? | 0:12:49 | 0:12:53 | |

If so, the answer will be here, in France. | 0:12:53 | 0:12:56 | |

Fontainebleau Palace just outside Paris is a perfect example | 0:12:56 | 0:13:01 | |

of the world that the revolution revolted against. | 0:13:01 | 0:13:04 | |

Monarchies with a divine right to rule, | 0:13:05 | 0:13:08 | |

absolute power and the privileges that came with it. | 0:13:08 | 0:13:11 | |

Privileges like this 1,500-room chateau, | 0:13:11 | 0:13:14 | |

property of the French royalty since the Middle Ages. | 0:13:14 | 0:13:18 | |

The French monarchy was the most entrenched in Europe | 0:13:19 | 0:13:21 | |

and appeared to be everlasting. | 0:13:21 | 0:13:24 | |

And this was just one of their playgrounds. | 0:13:24 | 0:13:26 | |

As far back as the 12th century, French kings and queens | 0:13:26 | 0:13:29 | |

and their families and their guests | 0:13:29 | 0:13:32 | |

and their servants and their retinues | 0:13:32 | 0:13:34 | |

had come here to escape the heat of Paris. | 0:13:34 | 0:13:37 | |

And walking around out here, that sense of solidity, | 0:13:37 | 0:13:42 | |

of confidence, of complacency even, is very apparent. | 0:13:42 | 0:13:46 | |

And that's just the exteriors. | 0:13:46 | 0:13:48 | |

Compared to the interiors, this is...understatement. | 0:13:48 | 0:13:52 | |

The 18th century diplomat Talleyrand said, | 0:13:58 | 0:14:01 | |

"Those who have not lived through the years around 1789 | 0:14:01 | 0:14:06 | |

"cannot know what is meant by the pleasure of life." | 0:14:06 | 0:14:09 | |

Here in Fontainebleau, you can understand what he was getting at. | 0:14:09 | 0:14:13 | |

The French King Louis XVI and his bride, Marie Antoinette, | 0:14:14 | 0:14:17 | |

stayed here between October and November 1786. | 0:14:17 | 0:14:22 | |

Among the lavish festivities laid on, the royal couple attended | 0:14:22 | 0:14:26 | |

a specially-staged ballet here in this beautiful ballroom. | 0:14:26 | 0:14:30 | |

They also had a chance to examine some new building work, | 0:14:34 | 0:14:37 | |

including this room, a gift from the King to his Queen. | 0:14:37 | 0:14:41 | |

This exquisite room, with its own en-suite bathroom, | 0:14:44 | 0:14:48 | |

was Marie Antoinette's private retreat. | 0:14:48 | 0:14:50 | |

It's all set in silver, which you can see on the wall coverings there, | 0:14:50 | 0:14:55 | |

and there's more silver in these two pieces - | 0:14:55 | 0:14:58 | |

which are both original, they were here. | 0:14:58 | 0:15:01 | |

This roll-top desk and this hopper table. | 0:15:01 | 0:15:05 | |

And it's silver, and it's mother-of-pearl, | 0:15:05 | 0:15:07 | |

and there's brass and there's bronze and there's boxwood. | 0:15:07 | 0:15:10 | |

I mean, they are quite beautiful. | 0:15:10 | 0:15:12 | |

On her first visit to Paris, the 14-year-old Austrian princess | 0:15:17 | 0:15:21 | |

was greeted like some sort of rock star or celebrity. | 0:15:21 | 0:15:25 | |

Tens of thousands of people turned out to see her | 0:15:25 | 0:15:29 | |

and 30 of them were trampled to death in the crush. | 0:15:29 | 0:15:32 | |

But by 1789, stories of this sort of luxurious excess | 0:15:32 | 0:15:38 | |

had turned public opinion against her. | 0:15:38 | 0:15:41 | |

ANGRY SHOUTS | 0:15:43 | 0:15:45 | |

The queen's lavish lifestyle did not go down well with a population | 0:15:49 | 0:15:52 | |

struggling with years of bad harvests, | 0:15:52 | 0:15:56 | |

high taxes and corruption. | 0:15:56 | 0:15:57 | |

Resentment against the aristocracy and the clergy grew. | 0:15:58 | 0:16:03 | |

And with it came a hunger for change, for freedom. | 0:16:03 | 0:16:07 | |

In the long hot summer of 1789, the discontent reached breaking point | 0:16:11 | 0:16:16 | |

and Paris was consumed by chaos, riots and looting. | 0:16:16 | 0:16:20 | |

Then on the 14th of July, a mob stormed the Bastille, | 0:16:20 | 0:16:24 | |

a fortress and prison that stood as a symbol of royal power. | 0:16:24 | 0:16:28 | |

Paris was now in rebel hands. Fontainebleau Palace was plundered. | 0:16:30 | 0:16:35 | |

The French revolution had begun. | 0:16:35 | 0:16:37 | |

This is Le Cafe Procope, Paris' oldest cafe, and supposedly | 0:16:42 | 0:16:46 | |

the place where Voltaire drank over 40 cups of coffee a day. | 0:16:46 | 0:16:51 | |

It's also the place where the leaders of the French Revolution | 0:16:51 | 0:16:55 | |

met regularly - Danton, Robespierre and Marat sat here | 0:16:55 | 0:17:00 | |

plotting the events that would etch themselves | 0:17:00 | 0:17:03 | |

in the imagination of a generation. | 0:17:03 | 0:17:05 | |

Across the continent, those inspired | 0:17:05 | 0:17:07 | |

included Europe's leading thinkers and artists - | 0:17:07 | 0:17:11 | |

Shelley, Coleridge, Goethe, Schiller. | 0:17:11 | 0:17:13 | |

And of course, Beethoven. | 0:17:13 | 0:17:15 | |

The English poet Wordsworth wrote, | 0:17:19 | 0:17:21 | |

"Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive | 0:17:21 | 0:17:23 | |

"but to be young was very heaven." | 0:17:23 | 0:17:26 | |

Beethoven was just 19. | 0:17:26 | 0:17:28 | |

The old feudal order - the Ancien Regime - | 0:17:30 | 0:17:33 | |

was to be abolished, and its privileges, hierarchies, | 0:17:33 | 0:17:36 | |

laws, courts and taxes would all be swept away. | 0:17:36 | 0:17:40 | |

On August 26th, 1789, the National Assembly, | 0:17:40 | 0:17:44 | |

based in this building here, | 0:17:44 | 0:17:47 | |

issued a guiding founding manifesto for how it would work. | 0:17:47 | 0:17:52 | |

It was called the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. | 0:17:52 | 0:17:56 | |

In England, in Germany, and right across Europe, | 0:17:58 | 0:18:01 | |

there were many, including Beethoven, who hoped that this | 0:18:01 | 0:18:04 | |

might be the start of a new era, this might be year zero, | 0:18:04 | 0:18:08 | |

where the Enlightenment ideal of a system of governance based | 0:18:08 | 0:18:12 | |

on freedom, equality and common good would finally become a reality. | 0:18:12 | 0:18:18 | |

It's generally accepted that Beethoven believed | 0:18:23 | 0:18:25 | |

in the ideals of the revolution during these heady early days. | 0:18:25 | 0:18:29 | |

But what's the evidence that those ideals later found their way | 0:18:29 | 0:18:33 | |

into the Fifth Symphony's first four notes? | 0:18:33 | 0:18:36 | |

I think it's a clandestine, subversive way | 0:18:37 | 0:18:41 | |

of articulating immensely strongly-held beliefs | 0:18:41 | 0:18:45 | |

and the fact is that there is this French Revolutionary Hymn | 0:18:45 | 0:18:49 | |

by Cherubini, the Hymne du Pantheon, which has a sort of rabble rousing | 0:18:49 | 0:18:54 | |

little chorus - "Nous jurons tous, le fer en main" - we all swear, | 0:18:54 | 0:19:00 | |

sword in hand - "De mourir pour la Republique" - | 0:19:00 | 0:19:03 | |

to die for the Republic - | 0:19:03 | 0:19:05 | |

"et pour les droits du genre humain" - and for the rights of man. | 0:19:05 | 0:19:08 | |

In rehearsals, John Eliot and his orchestra | 0:19:08 | 0:19:11 | |

performed this chorus for us. | 0:19:11 | 0:19:13 | |

# Nous jurons tous | 0:19:13 | 0:19:16 | |

# Nous jurons tous le fer en main. # | 0:19:16 | 0:19:20 | |

OK, slowly. One and two and one... | 0:19:20 | 0:19:23 | |

# Nous jurons tous le fer en main | 0:19:23 | 0:19:26 | |

# Nous jurons tous le fer en main... # | 0:19:26 | 0:19:29 | |

John Eliot sees a similarity to Beethoven's opening notes. | 0:19:29 | 0:19:33 | |

MUSIC PLAYS: Symphony No. 5 by Beethoven | 0:19:33 | 0:19:38 | |

Sounds familiar, doesn't it? | 0:19:42 | 0:19:43 | |

It's not just simply against fate or death or disaster, | 0:19:43 | 0:19:47 | |

it's exuberant, an enormous feeling of, "Yeah, we can do it. | 0:19:47 | 0:19:53 | |

"It's within human capacity to do it." | 0:19:53 | 0:19:55 | |

Where did you get the idea originally | 0:19:55 | 0:19:58 | |

that this is what he was up to? | 0:19:58 | 0:20:00 | |

It's not in the least bit original. I'm afraid I read it | 0:20:00 | 0:20:03 | |

when I was a student in Paris in the late '60s | 0:20:03 | 0:20:06 | |

and it was a German musicologist Arnold Schmitz who had | 0:20:06 | 0:20:11 | |

suggested there might be a rapport between or a link between his views | 0:20:11 | 0:20:15 | |

and the French revolutionary hymns which were in circulation. | 0:20:15 | 0:20:19 | |

And so I went off to the Bibliotheque nationale | 0:20:19 | 0:20:21 | |

and did a bit of sleuthing there and sure enough, the music kind of fits | 0:20:21 | 0:20:25 | |

the themes that Beethoven introduces in the first movement in the famous | 0:20:25 | 0:20:29 | |

"ba-ba-ba-baam" which goes, "Nous jurons tous, le fer en main," which | 0:20:29 | 0:20:35 | |

gives you a sort of clue to the type of rhetoric and the tempo, actually. | 0:20:35 | 0:20:40 | |

MUSIC PLAYS: Symphony No. 5 by Beethoven | 0:20:40 | 0:20:45 | |

Luigi Cherubini, an Italian composer who supported the | 0:20:45 | 0:20:49 | |

revolution and settled in France, wrote his hymn in honour of | 0:20:49 | 0:20:53 | |

this building in the heart of Paris - the Pantheon. | 0:20:53 | 0:20:56 | |

Its history is steeped in the ideal of fraternite - brotherhood - | 0:20:59 | 0:21:03 | |

that John Eliot believes drives the Fifth Symphony's first movement. | 0:21:03 | 0:21:07 | |

The Pantheon was built as a church. | 0:21:11 | 0:21:14 | |

But, in 1791, was transformed into an altar of liberty | 0:21:14 | 0:21:18 | |

and a secular shrine for great men. | 0:21:18 | 0:21:21 | |

In the crypt below are buried two French philosophers | 0:21:22 | 0:21:25 | |

who inspired the revolution. | 0:21:25 | 0:21:27 | |

Here's the man known as Voltaire. | 0:21:27 | 0:21:31 | |

And just across the way, Jean Jacques Rousseau. | 0:21:31 | 0:21:34 | |

It's the perfect place to find out more about | 0:21:36 | 0:21:39 | |

the French revolutionary music that Beethoven may have drawn on. | 0:21:39 | 0:21:42 | |

There were many hymns written for the revolution. | 0:21:44 | 0:21:47 | |

So the one by Cherubini is particular in that it was | 0:21:47 | 0:21:52 | |

especially grand and it called for a huge orchestra - | 0:21:52 | 0:21:57 | |

77 players, which was very big at the time. | 0:21:57 | 0:22:00 | |

Would Beethoven have known Cherubini's work? | 0:22:00 | 0:22:04 | |

Beethoven certainly knew Cherubini's works because they were | 0:22:04 | 0:22:08 | |

published and they were there for everyone to read and play from. | 0:22:08 | 0:22:12 | |

He would also have known him because Beethoven was in contact with French | 0:22:12 | 0:22:17 | |

musicians like Kreutzer, who gave his name to the Kreutzer Sonata. | 0:22:17 | 0:22:22 | |

So I'm sure that these musicians didn't only make music together | 0:22:22 | 0:22:27 | |

but they must have talked and read music and discussed it. | 0:22:27 | 0:22:30 | |

There's a very touching anecdote about French soldiers | 0:22:30 | 0:22:36 | |

visiting Beethoven and making music with him. | 0:22:36 | 0:22:39 | |

So if I could go back in time, | 0:22:39 | 0:22:44 | |

this is one of the things I'd like to witness. | 0:22:44 | 0:22:46 | |

And what do you think the appeal to Beethoven was of this music? | 0:22:46 | 0:22:51 | |

There is the elan. There is the energy, as you say, | 0:22:51 | 0:22:56 | |

and "energie" was one of the key words of philosophy at the time. | 0:22:56 | 0:23:03 | |

The revolution was a time of energy after | 0:23:03 | 0:23:08 | |

the decadence of the Ancien Regime. | 0:23:08 | 0:23:10 | |

Music was public by definition in these occasions | 0:23:10 | 0:23:16 | |

and it served the function of creating a sense of collective | 0:23:16 | 0:23:19 | |

feeling around the revolution. | 0:23:19 | 0:23:22 | |

So it seems likely that Beethoven did know | 0:23:25 | 0:23:27 | |

about this new, radical form of music, a public art | 0:23:27 | 0:23:31 | |

that could express powerful political messages. | 0:23:31 | 0:23:34 | |

And if John Eliot's theory is correct, | 0:23:34 | 0:23:36 | |

that was exactly the effect that Beethoven was after. | 0:23:36 | 0:23:40 | |

Rouget de Lille who composed La Marseillaise, | 0:23:40 | 0:23:43 | |

he was an officer and not a professional musician. | 0:23:43 | 0:23:47 | |

There's a famous painting showing Rouget de Lille | 0:23:47 | 0:23:51 | |

declaiming his Marseillaise when he first had the idea. | 0:23:51 | 0:23:54 | |

But then it became a kind of national anthem. | 0:23:54 | 0:23:58 | |

MUSIC PLAYS: La Marseillaise by Rouget de Lille | 0:23:58 | 0:24:05 | |

But he hit on this fantastic tune, | 0:24:07 | 0:24:11 | |

which is characterised by its elan, | 0:24:11 | 0:24:17 | |

the way it goes for the high notes. | 0:24:17 | 0:24:19 | |

# Allons enfants de la Patrie. # | 0:24:19 | 0:24:21 | |

And although nobody can sing it properly | 0:24:21 | 0:24:25 | |

because the note is a bit too high. | 0:24:25 | 0:24:27 | |

It's too high, yeah, and then it goes very low again - | 0:24:27 | 0:24:30 | |

# Mugir ces feroces soldats. # | 0:24:30 | 0:24:32 | |

Especially on football fields it's rather painful. | 0:24:32 | 0:24:35 | |

It's precisely this "energie", | 0:24:39 | 0:24:41 | |

a kind of musical call to arms, that John Eliot tries to | 0:24:41 | 0:24:45 | |

capture and communicate in his own performance of Beethoven's Fifth. | 0:24:45 | 0:24:50 | |

Schmitz' theory, which I profoundly believe in | 0:24:50 | 0:24:53 | |

and I feel it gives tremendous edge in the performance, it's not | 0:24:53 | 0:24:57 | |

provable in absolute terms. It's a way in | 0:24:57 | 0:25:02 | |

and I think it's a good corrective or it's a helpful corrective | 0:25:02 | 0:25:06 | |

to the rather wishy-washy, you know, fate and all the rest of it. | 0:25:06 | 0:25:11 | |

MUSIC PLAYS: Symphony No. 5 by Beethoven | 0:25:11 | 0:25:18 | |

Beethoven himself was far from a wishy-washy character. | 0:25:33 | 0:25:37 | |

He was a notoriously tough and turbulent personality. | 0:25:37 | 0:25:40 | |

But if he was also a radical who supported French revolutionary | 0:25:40 | 0:25:44 | |

ideals, where did all that come from? | 0:25:44 | 0:25:47 | |

Perhaps the answer lies in the composer's early life in Germany. | 0:25:47 | 0:25:50 | |

Never an easy man, Beethoven, and this is the archetypal | 0:25:52 | 0:25:55 | |

portrayal of him - intense, furious, brooding, heaven-storming. | 0:25:55 | 0:26:01 | |

And this extraordinary, | 0:26:01 | 0:26:02 | |

contrary personality was shaped here in Bonn during an unhappy childhood | 0:26:02 | 0:26:08 | |

and a troubled youth, which made its mark on him as man and as artist. | 0:26:08 | 0:26:13 | |

Beethoven was born in 1770, | 0:26:19 | 0:26:21 | |

and grew up here at what's now called the Beethoven Haus. | 0:26:21 | 0:26:26 | |

The infant Beethoven joined a musical family | 0:26:26 | 0:26:30 | |

in a very musical city. | 0:26:30 | 0:26:31 | |

His beloved grandfather was Kapellmeister, | 0:26:31 | 0:26:34 | |

resident composer at Bonn's court. | 0:26:34 | 0:26:36 | |

But he died when the boy was only three. | 0:26:37 | 0:26:41 | |

So, how happy a home was the Beethoven Haus? | 0:26:41 | 0:26:44 | |

This is it, is it? | 0:26:45 | 0:26:47 | |

Yeah. We believe this is the birth room, | 0:26:47 | 0:26:50 | |

but in fact we are sure this is the bedroom of the parents. | 0:26:50 | 0:26:55 | |

-Right. -His father has been not so gifted as his grandfather. | 0:26:55 | 0:27:02 | |

This has perhaps been a problem. | 0:27:02 | 0:27:05 | |

If you have a great father and a great son, | 0:27:05 | 0:27:08 | |

being in the middle of it's not very easy. | 0:27:08 | 0:27:10 | |

He had some problems with alcohol. | 0:27:10 | 0:27:14 | |

You would say Beethoven had a complex relationship | 0:27:14 | 0:27:16 | |

with his father? | 0:27:16 | 0:27:18 | |

Yes, it is certainly true. It's not a normal family. | 0:27:18 | 0:27:21 | |

Beethoven's father had to train him on music, on keyboard, | 0:27:21 | 0:27:25 | |

on violin and Beethoven had to learn this, | 0:27:25 | 0:27:31 | |

and the method of the time is punishment... | 0:27:31 | 0:27:35 | |

Involved hitting him? | 0:27:35 | 0:27:37 | |

Yeah. For all children, not only for Beethoven. | 0:27:37 | 0:27:39 | |

Beethoven as a child, he doesn't seem to have been happy. | 0:27:39 | 0:27:43 | |

He played with his brothers. He played with other children, | 0:27:43 | 0:27:47 | |

but not very much. | 0:27:47 | 0:27:49 | |

He had to practise very much and he was very shy | 0:27:49 | 0:27:52 | |

because he didn't go to school a very long time | 0:27:52 | 0:27:55 | |

so he was very unsure of himself. | 0:27:55 | 0:27:59 | |

When Beethoven was ten, | 0:28:02 | 0:28:04 | |

his father took him out of school to concentrate on music. | 0:28:04 | 0:28:08 | |

He hired a teacher, Christian Gottlob Neefe, who some believe | 0:28:08 | 0:28:12 | |

influenced not only Beethoven's music, but his political ideas. | 0:28:12 | 0:28:16 | |

This is Bonn's Palace Chapel, the rather grand venue | 0:28:19 | 0:28:22 | |

where Neefe, who was court organist, taught the young Ludwig to play. | 0:28:22 | 0:28:27 | |

Beethoven played the viola, the piano and the organ, | 0:28:29 | 0:28:33 | |

all brilliantly, but he wasn't an infant prodigy as a composer. | 0:28:33 | 0:28:38 | |

He wasn't like the young Mozart, who by the age of ten | 0:28:38 | 0:28:41 | |

had knocked out a series of symphonies | 0:28:41 | 0:28:44 | |

and concertos and even an opera. | 0:28:44 | 0:28:46 | |

No, this was a boy who needed nurturing. | 0:28:46 | 0:28:49 | |

And Neefe was the man for the job. | 0:28:49 | 0:28:51 | |

He'd had problems with his own parents, | 0:28:51 | 0:28:54 | |

and he helped give the young boy a voice of his own, | 0:28:54 | 0:28:57 | |

both as a player and as a composer, | 0:28:57 | 0:29:00 | |

away from the influence of his father. | 0:29:00 | 0:29:02 | |

And when at the age of 12 or 13, the boy said to his teacher, | 0:29:03 | 0:29:07 | |

"Look, I actually want to write some piano sonatas," | 0:29:07 | 0:29:10 | |

being a composer himself, he said, "Go for it," | 0:29:10 | 0:29:13 | |

and Beethoven did and we have, at the age of 13, | 0:29:13 | 0:29:16 | |

his first three piano sonatas, absolutely incredible. | 0:29:16 | 0:29:19 | |

Neefe occasionally let Ludwig stand in for him | 0:29:19 | 0:29:23 | |

as court organist, playing here for Bonn's ruler, the elector. | 0:29:23 | 0:29:28 | |

Neefe introduced him to the works of JS Bach, | 0:29:28 | 0:29:31 | |

who at the time was considered difficult, or was just unknown. | 0:29:31 | 0:29:35 | |

And it wasn't only unorthodox music that interested Neefe. | 0:29:35 | 0:29:39 | |

He was a member of the Freemasons, of the Illuminati, | 0:29:39 | 0:29:42 | |

of something called the Reading Group, which were slightly secretive | 0:29:42 | 0:29:47 | |

groups of intelligent young men who were playing with ideas that | 0:29:47 | 0:29:51 | |

would make the owners of these sorts of palaces distinctly uncomfortable. | 0:29:51 | 0:29:56 | |

At the time the boy Ludwig was studying music with Neefe, | 0:29:58 | 0:30:03 | |

the enlightenment was sweeping Europe in all branches of the arts. | 0:30:03 | 0:30:08 | |

Literature, the theatre, music, philosophy and, for the first time, | 0:30:08 | 0:30:14 | |

the theory of the divine right of the monarchy was being questioned. | 0:30:14 | 0:30:19 | |

"Hang on a minute, these people don't have a divine right | 0:30:19 | 0:30:22 | |

"to be ruling over us." | 0:30:22 | 0:30:25 | |

And Neefe, a born revolutionary at heart, | 0:30:25 | 0:30:27 | |

he's bound to have just chatted to Ludwig and as a 12-year-old boy, | 0:30:27 | 0:30:31 | |

you're going to listen impressed, aren't you? | 0:30:31 | 0:30:34 | |

So I think Neefe was more than just a teacher for the young Ludwig - | 0:30:34 | 0:30:37 | |

he was a kind of guru. | 0:30:37 | 0:30:39 | |

This guru had no time for the Catholic Church, | 0:30:39 | 0:30:43 | |

but he was religious and also had faith that mankind | 0:30:43 | 0:30:46 | |

could create a better society. | 0:30:46 | 0:30:49 | |

It's possible to detect the influence of these views | 0:30:49 | 0:30:52 | |

in the second movement of his pupil's Fifth Symphony. | 0:30:52 | 0:30:56 | |

THEY PLAY SECOND MOVEMENT | 0:30:56 | 0:30:58 | |

It's very gentle and lissom and in the other movements, | 0:31:17 | 0:31:23 | |

there's often incredible beauty and a softness. | 0:31:23 | 0:31:26 | |

The other thing that is so new with Beethoven | 0:31:39 | 0:31:43 | |

and so sort of enticing about the Fifth Symphony | 0:31:43 | 0:31:48 | |

is the extraordinary kind of humanity of the man, | 0:31:48 | 0:31:53 | |

the humanity of his breadth of vision. | 0:31:53 | 0:31:55 | |

We don't know a lot about Beethoven's religious views. | 0:32:05 | 0:32:09 | |

One senses that he had religious views | 0:32:09 | 0:32:15 | |

that were optimistic. | 0:32:15 | 0:32:18 | |

And you get a kind of foretaste of that in this second movement | 0:32:28 | 0:32:33 | |

of the Fifth Symphony that it feels like a prayer. | 0:32:33 | 0:32:36 | |

In contrast to the struggle and the strife of the first movement | 0:32:43 | 0:32:48 | |

that Beethoven is suggesting that in humanity, | 0:32:48 | 0:32:52 | |

there is a capacity to perfect itself. | 0:32:52 | 0:32:56 | |

So that it's a prayer in that sense for a better soul, | 0:33:01 | 0:33:05 | |

a better human being. | 0:33:05 | 0:33:07 | |

In his mission to express the real meaning of the Fifth Symphony, | 0:33:12 | 0:33:16 | |

John Eliot and his orchestra insist on using instruments | 0:33:16 | 0:33:19 | |

from Beethoven's time. | 0:33:19 | 0:33:22 | |

They were in transition between baroque and modern design, | 0:33:22 | 0:33:25 | |

and the musical experience is very different, | 0:33:25 | 0:33:28 | |

for the audience and the players. | 0:33:28 | 0:33:30 | |

I mean, of course one can play this music on a modern set-up, | 0:33:32 | 0:33:36 | |

but it produces a different type of ethos, doesn't it? | 0:33:36 | 0:33:41 | |

-Pete, can you show us? -It's a different sound. | 0:33:41 | 0:33:44 | |

Yes, this is a lovely old Italian violin with all gut strings on, | 0:33:44 | 0:33:48 | |

including an original type of G-string and it's sort of... | 0:33:48 | 0:33:54 | |

There is a definite purity about that, which I find very attractive. | 0:34:04 | 0:34:09 | |

So everybody in the orchestra has these strings | 0:34:09 | 0:34:12 | |

and it changes the string sound tremendously, I think. | 0:34:12 | 0:34:16 | |

It's more layered, isn't it? You get more different textures. | 0:34:16 | 0:34:18 | |

It's a different feel and a different sort of sensitivity | 0:34:18 | 0:34:21 | |

that's required. I have got here... | 0:34:21 | 0:34:23 | |

..exactly the same maker, | 0:34:25 | 0:34:27 | |

but this one has got modern strings on. | 0:34:27 | 0:34:29 | |

They're sort of nylon, metal. | 0:34:29 | 0:34:32 | |

It's a completely different type of sound, | 0:34:42 | 0:34:44 | |

you have to play it in a different way. | 0:34:44 | 0:34:46 | |

It's more powerful, it's more fruity, | 0:34:46 | 0:34:48 | |

it's got more sheer density, hasn't it? | 0:34:48 | 0:34:52 | |

But that one... | 0:34:52 | 0:34:53 | |

..just go back to that, cos that has... | 0:34:55 | 0:34:57 | |

It's got a purer sort of... | 0:34:57 | 0:34:58 | |

The result is that you get a much more multi-layered strata of sounds, | 0:35:18 | 0:35:26 | |

not all kind of curdling and amalgamating | 0:35:26 | 0:35:28 | |

in the way that they do, | 0:35:28 | 0:35:30 | |

or they tend to do in a modern symphony orchestra. | 0:35:30 | 0:35:32 | |

That's the good news, | 0:35:35 | 0:35:36 | |

but playing on these instruments has its challenges too. | 0:35:36 | 0:35:39 | |

And a thing like this, | 0:35:43 | 0:35:44 | |

which hasn't altered much in structure or in shape | 0:35:44 | 0:35:48 | |

since Monteverdi's day and is only held together, what...? | 0:35:48 | 0:35:53 | |

By a block of wood and some cord holding the thing together. | 0:35:53 | 0:35:56 | |

There is no soldered bits or anything like that. | 0:35:56 | 0:35:58 | |

Not like a modern set-up. | 0:35:58 | 0:36:00 | |

It feels like it is going to come to pieces in your hands. | 0:36:00 | 0:36:02 | |

And the challenges are immense | 0:36:07 | 0:36:09 | |

because these instruments of Beethoven's | 0:36:09 | 0:36:11 | |

are hugely fragile and compromised. | 0:36:11 | 0:36:17 | |

If you push them too hard, they splinter, they crack, they squawk. | 0:36:17 | 0:36:21 | |

With these instruments, because of their fragility | 0:36:27 | 0:36:30 | |

and their technical fallibility, you have to push them to the nth degree. | 0:36:30 | 0:36:34 | |

I had a conversation with a friend of mine who runs a Formula One team | 0:36:45 | 0:36:49 | |

and he was saying that his ultimate Formula One car, | 0:36:49 | 0:36:52 | |

the moment it crosses that finish line, | 0:36:52 | 0:36:55 | |

it would fall to pieces. | 0:36:55 | 0:36:57 | |

You know, it couldn't go another metre and when we play this music | 0:36:57 | 0:37:01 | |

on these instruments, I feel we are the same. | 0:37:01 | 0:37:03 | |

I mean, this is... | 0:37:17 | 0:37:20 | |

This is indomitable, relentless, | 0:37:20 | 0:37:23 | |

unreasonable music and Beethoven seems to me | 0:37:23 | 0:37:26 | |

a very unreasonable man | 0:37:26 | 0:37:28 | |

who makes unreasonable demands of these instruments | 0:37:28 | 0:37:31 | |

and we couldn't give it any more on these. | 0:37:31 | 0:37:33 | |

This unreasonable, rebellious side developed | 0:37:58 | 0:38:02 | |

when Beethoven enrolled at Bonn University in 1789. | 0:38:02 | 0:38:05 | |

The French Revolution took place that very year | 0:38:08 | 0:38:10 | |

and the young Beethoven immersed himself in the radical ideas | 0:38:10 | 0:38:14 | |

that swept through the university. | 0:38:14 | 0:38:16 | |

Like students before and since, | 0:38:18 | 0:38:20 | |

Beethoven spent time in the town's taverns, | 0:38:20 | 0:38:22 | |

where his fellows debated philosophy and literature. | 0:38:22 | 0:38:26 | |

And, of course, tried to seduce young women. | 0:38:26 | 0:38:29 | |

This tavern's claim to fame is that it was here that the young Beethoven | 0:38:31 | 0:38:36 | |

danced with his first love, Barbe Koch. | 0:38:36 | 0:38:39 | |

It's a charming image, but from what we know about Beethoven, | 0:38:39 | 0:38:43 | |

not terribly likely, given that he was notoriously badly coordinated | 0:38:43 | 0:38:47 | |

and socially awkward, particularly around women. | 0:38:47 | 0:38:51 | |

Light-hearted flirtation was not really his thing, | 0:38:51 | 0:38:54 | |

more unrequited anguish. | 0:38:54 | 0:38:56 | |

But his personality perfectly suited | 0:38:56 | 0:38:59 | |

the prevailing arts movement of the time, | 0:38:59 | 0:39:02 | |

Sturm und Drang, Storm and Strife. | 0:39:02 | 0:39:06 | |

You couldn't get more Sturm and Drang | 0:39:07 | 0:39:09 | |

than the German playwright Friedrich Schiller | 0:39:09 | 0:39:12 | |

and he would have a lasting influence on Beethoven | 0:39:12 | 0:39:15 | |

and his Fifth Symphony. | 0:39:15 | 0:39:17 | |

Danke schoen. | 0:39:17 | 0:39:18 | |

Beethoven went to see a production of Schiller's The Robbers | 0:39:19 | 0:39:23 | |

here in Bonn. | 0:39:23 | 0:39:24 | |

This was an epic melodrama which featured a hero who was a student, | 0:39:24 | 0:39:29 | |

a revolutionary who decided to rebel against what he saw as | 0:39:29 | 0:39:33 | |

the hypocrisy of class and religion and economic inequality in Germany. | 0:39:33 | 0:39:39 | |

You can imagine Beethoven was a fan, but it was more than that. | 0:39:39 | 0:39:43 | |

When the play premiered at Mannheim in 1782, an eyewitness wrote, | 0:39:43 | 0:39:48 | |

"The theatre was like a madhouse with people rolling their eyes | 0:39:48 | 0:39:51 | |

"and clenching their fists and outcries from the audience. | 0:39:51 | 0:39:55 | |

"Strangers fell with sobs into each other's arms, | 0:39:55 | 0:39:58 | |

"women became unconscious and had to leave the theatre. | 0:39:58 | 0:40:01 | |

"It was a general uproar, a chaos." | 0:40:01 | 0:40:05 | |

That was the effect that real art could have on an audience. | 0:40:05 | 0:40:09 | |

This is not entertainment for people, | 0:40:13 | 0:40:15 | |

this is a form of experience, of drama, | 0:40:15 | 0:40:19 | |

of perhaps, at that time, almost unparalleled power and strength. | 0:40:19 | 0:40:24 | |

I think that gives Beethoven a vision of what an artist | 0:40:24 | 0:40:27 | |

can do with an audience. | 0:40:27 | 0:40:29 | |

I can't prove it, but the relationship of how audiences felt | 0:40:30 | 0:40:34 | |

about Schiller's The Robbers in about 1780 or 1790 or so | 0:40:34 | 0:40:39 | |

and Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is unmistakable. | 0:40:39 | 0:40:43 | |

Beethoven remained less lucky in love than music, | 0:40:43 | 0:40:47 | |

but he never stopped believing in the possibility of romance. | 0:40:47 | 0:40:50 | |

Beethoven's history with women is not a hugely successful story. | 0:40:51 | 0:40:57 | |

We know for sure that he proposed marriage three times | 0:40:57 | 0:41:00 | |

to three different women. We know he was turned down each time. | 0:41:00 | 0:41:04 | |

Some experts believe Beethoven may have died a reluctant virgin | 0:41:04 | 0:41:09 | |

and it's very possible that he channelled his unrequited passion | 0:41:09 | 0:41:13 | |

into his music, or into his politics, or perhaps both. | 0:41:13 | 0:41:17 | |

Until the revolution, Beethoven's own compositions | 0:41:19 | 0:41:22 | |

had been rather conservative, | 0:41:22 | 0:41:24 | |

but after it, he began to take more risks, | 0:41:24 | 0:41:27 | |

writing more challenging works. | 0:41:27 | 0:41:29 | |

Some of them were overtly political | 0:41:29 | 0:41:32 | |

and one of these feeds directly into the Fifth Symphony. | 0:41:32 | 0:41:36 | |

# Wer, wer ist ein freier Mann...? # | 0:41:36 | 0:41:41 | |

In 1792, Beethoven set The Free Man, a poem by Gottlieb Konrad Pfeffel, | 0:41:41 | 0:41:48 | |

to music. | 0:41:48 | 0:41:49 | |

# Wer ist ein freier Mann? | 0:41:51 | 0:41:54 | |

# Ein freier, freier Mann? # | 0:41:54 | 0:41:57 | |

This is the first published edition | 0:41:58 | 0:42:00 | |

of the score of some early Beethoven compositions, | 0:42:00 | 0:42:04 | |

including Der Freie Mann, | 0:42:04 | 0:42:07 | |

a definition of what makes a free man | 0:42:07 | 0:42:11 | |

and, really, it's a description of Beethoven himself. | 0:42:11 | 0:42:15 | |

The words go like this: "Wer ist ein freier Mann?" - | 0:42:15 | 0:42:19 | |

"Who is a free man? | 0:42:19 | 0:42:21 | |

"One who, enclosed within himself, can set at naught the venal favour | 0:42:21 | 0:42:27 | |

"of great and small alike - he is a free man." | 0:42:27 | 0:42:33 | |

It's pretty heady stuff, | 0:42:33 | 0:42:34 | |

but this wasn't just some youthful folly on Beethoven's part. | 0:42:34 | 0:42:38 | |

The opening bars of Der Freie Mann are identical | 0:42:38 | 0:42:43 | |

to the opening of the fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony, | 0:42:43 | 0:42:46 | |

also set in C major. | 0:42:46 | 0:42:48 | |

# Wer ist ein freier Mann...? # | 0:42:48 | 0:42:53 | |

Beethoven first introduces this musical motif of freedom achieved | 0:42:53 | 0:42:57 | |

in the second movement of his Fifth Symphony. | 0:42:57 | 0:43:00 | |

# Ein freier, freier Mann. # | 0:43:00 | 0:43:02 | |

Der Freie Mann dates from many years earlier | 0:43:08 | 0:43:12 | |

and surely prefigures the Fifth | 0:43:12 | 0:43:16 | |

in a certain, at least embryonic, but nevertheless significant way. | 0:43:16 | 0:43:21 | |

Already here... | 0:43:21 | 0:43:22 | |

..is the rising triadic idea which has some parallel | 0:43:27 | 0:43:33 | |

already in that early song The Free Man. | 0:43:33 | 0:43:37 | |

THEY PLAY SECOND MOVEMENT | 0:43:46 | 0:43:49 | |

Even though he's hinting at the C Major of the triumph | 0:44:07 | 0:44:10 | |

that's going to eventually come in the last movement, | 0:44:10 | 0:44:13 | |

the eclat triomphal to which we're all moving towards, | 0:44:13 | 0:44:19 | |

it's a foretaste and yet it's aborted. | 0:44:19 | 0:44:23 | |

No sooner have they arrived at that chord than it disappears, | 0:44:29 | 0:44:34 | |

it's sort of like a puff of smoke, it's gone into the ether. | 0:44:34 | 0:44:37 | |

So one could say that the goal of the symphony - freedom - | 0:44:48 | 0:44:51 | |

has not yet been reached. | 0:44:51 | 0:44:52 | |

In 1792, Beethoven left Bonn for good. | 0:44:59 | 0:45:03 | |

The ambitious 22-year-old was keen to make his musical mark, | 0:45:03 | 0:45:08 | |

so he moved to Vienna, the Austrian capital, | 0:45:08 | 0:45:10 | |

where he would write the Fifth Symphony in 1807. | 0:45:10 | 0:45:13 | |

By this time, the revolution that Beethoven supported | 0:45:15 | 0:45:18 | |

was spreading across Europe | 0:45:18 | 0:45:21 | |

and it made his trip a troubled one. | 0:45:21 | 0:45:23 | |

Beethoven was travelling through the middle of a war. | 0:45:25 | 0:45:28 | |

France was trying to export the revolution, | 0:45:28 | 0:45:31 | |

with which he sympathised, | 0:45:31 | 0:45:33 | |

into the country where he wanted to live and work. | 0:45:33 | 0:45:36 | |

French troops, many of them marching to the Marseillaise, | 0:45:38 | 0:45:41 | |

were advancing into Germany and towards Austria, | 0:45:41 | 0:45:44 | |

and defending troops were massing in the Rhineland. | 0:45:44 | 0:45:48 | |

Beethoven records in his diary that he had to tip his driver one thaler | 0:45:48 | 0:45:53 | |

because, "The fellow drove us at the risk of a whipping | 0:45:53 | 0:45:56 | |

"right through the Hessian lines," which were the German troops, | 0:45:56 | 0:45:59 | |

"going like crazy." | 0:45:59 | 0:46:01 | |

There are calmer ways to do the journey. | 0:46:02 | 0:46:04 | |

It would be surprising if Beethoven didn't have mixed feelings | 0:46:07 | 0:46:10 | |

as French troops threatened the city of his childhood | 0:46:10 | 0:46:14 | |

and it was becoming harder for him to support the realities | 0:46:14 | 0:46:17 | |

of the Revolution in France. | 0:46:17 | 0:46:18 | |

Events there were taking a much darker turn. | 0:46:20 | 0:46:23 | |

In 1793, just four years after the fall of the Bastille, | 0:46:23 | 0:46:27 | |

the ruling National Convention declared | 0:46:27 | 0:46:29 | |

that counter-revolutionaries would be executed. | 0:46:29 | 0:46:33 | |

King Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette, | 0:46:33 | 0:46:35 | |

were arrested and held captive. | 0:46:35 | 0:46:38 | |

And they weren't the only ones. | 0:46:38 | 0:46:41 | |

This grim-looking building is La Conciergerie, | 0:46:41 | 0:46:44 | |

used by the National Convention as a prison. | 0:46:44 | 0:46:47 | |

With no artificial light, | 0:46:48 | 0:46:49 | |

this must have been an even more forbidding and gloomy place. | 0:46:49 | 0:46:54 | |

Enemies of the Revolution were imprisoned here... | 0:46:59 | 0:47:02 | |

..before being dispatched by a specially invented new machine, | 0:47:05 | 0:47:09 | |

the guillotine. | 0:47:09 | 0:47:11 | |

At the time, the Convention, | 0:47:11 | 0:47:13 | |

who were ruling France in the name of the people, | 0:47:13 | 0:47:15 | |

congratulated itself on this humane form of execution. | 0:47:15 | 0:47:19 | |

On January 21st, 1793, the deposed king himself, Louis XVI, | 0:47:20 | 0:47:26 | |

was executed, publicly, and humanely. | 0:47:26 | 0:47:30 | |

And this is the chapel where his queen, Marie Antoinette, | 0:47:36 | 0:47:40 | |

prayed whilst imprisoned and awaiting her fate. | 0:47:40 | 0:47:44 | |

This is the original floor and this is the exact spot where she knelt. | 0:47:45 | 0:47:51 | |

On October 16th, 1793, | 0:47:53 | 0:47:56 | |

Marie Antoinette was dispatched to the guillotine. | 0:47:56 | 0:47:59 | |

And when the blade descended, the crowd shouted, "Vive La Nation!" | 0:47:59 | 0:48:05 | |

During the two-year Reign of Terror, | 0:48:07 | 0:48:09 | |

more than 2,700 people appeared before the Revolutionary Tribunal | 0:48:09 | 0:48:14 | |

in La Conciergerie's grand chamber. | 0:48:14 | 0:48:17 | |

The condemned prisoners were held in batches in that compound, | 0:48:19 | 0:48:23 | |

behind those gates, | 0:48:23 | 0:48:25 | |

and their relatives were allowed to come in and say a last goodbye. | 0:48:25 | 0:48:29 | |

The Revolution had begun to devour its own children, | 0:48:32 | 0:48:35 | |

and Schiller and the English poets publicly recanted, | 0:48:35 | 0:48:40 | |

and Coleridge even called for the restoration of the Ancien Regime. | 0:48:40 | 0:48:45 | |

Beethoven was as horrified as anyone else by the excesses | 0:48:45 | 0:48:48 | |

thrown up by the French Revolution, | 0:48:48 | 0:48:50 | |

but he didn't lose faith with the ideals and the principals behind it. | 0:48:50 | 0:48:55 | |

Vienna in 1793 was an unlikely setting to write a symphony | 0:49:02 | 0:49:07 | |

supporting the ideals of the French Revolution. | 0:49:07 | 0:49:10 | |

It was the capital of the centuries-old European dynastic power, | 0:49:13 | 0:49:18 | |

the Habsburg Empire, which was a major force in a military coalition | 0:49:18 | 0:49:22 | |

battling the French armies. | 0:49:22 | 0:49:24 | |

Viennese society was under threat, yet the paranoid upper classes | 0:49:28 | 0:49:32 | |

distracted themselves with fun and frivolity. | 0:49:32 | 0:49:35 | |

I suspect Beethoven would have seen plenty to disapprove of here, | 0:49:37 | 0:49:42 | |

but he also had very good reasons | 0:49:42 | 0:49:44 | |

to keep such political views to himself. | 0:49:44 | 0:49:46 | |

In a letter from August 1794, Beethoven wrote, | 0:49:53 | 0:49:57 | |

"I believe that as long as an Austrian can get his brown ale | 0:49:57 | 0:50:00 | |

"and his little sausages, he is not likely to revolt." | 0:50:00 | 0:50:03 | |

But he added ominously, | 0:50:05 | 0:50:07 | |

"People say that the gates leading to the suburbs | 0:50:07 | 0:50:09 | |

"are to be closed at 10pm. | 0:50:09 | 0:50:11 | |

"The soldiers have loaded their muskets with ball. | 0:50:11 | 0:50:15 | |

"You dare not raise your voice here | 0:50:15 | 0:50:16 | |

"or the police will take you into custody." | 0:50:16 | 0:50:19 | |

Austria seemed a bit like a police state. | 0:50:21 | 0:50:23 | |

So, why did the Austrians react so strongly to the events in France? | 0:50:26 | 0:50:30 | |

There was these family connections | 0:50:30 | 0:50:32 | |

between the French and the Austrian monarchy, | 0:50:32 | 0:50:35 | |

Marie Antoinette being an Austrian princess. | 0:50:35 | 0:50:39 | |

Right, so it was coming straight home? | 0:50:39 | 0:50:41 | |

And so, it was really coming straight home | 0:50:41 | 0:50:43 | |

and hitting the Habsburg family. | 0:50:43 | 0:50:46 | |

Did they clamp down on any sort of radical thinking? | 0:50:46 | 0:50:52 | |

The police was reorganised and much more centralised. | 0:50:52 | 0:50:56 | |

The idea was to involve as many people as possible | 0:50:56 | 0:51:01 | |

in spying on as many people as possible. | 0:51:01 | 0:51:04 | |

Do you think Beethoven would have been an obvious suspect? | 0:51:04 | 0:51:07 | |

I think he would have been a kind of an obvious target. | 0:51:07 | 0:51:13 | |

One can easily understand why he himself | 0:51:13 | 0:51:18 | |

tried to keep a low profile in his writings. | 0:51:18 | 0:51:22 | |

They would open letters, read letters. | 0:51:22 | 0:51:25 | |

I think he was quite aware of that | 0:51:25 | 0:51:27 | |

and probably kept also here a rather low profile. | 0:51:27 | 0:51:32 | |

The letters have jokes in them, but there's nothing dangerous there. | 0:51:32 | 0:51:36 | |

I think, you know, it's quite likely that they were | 0:51:36 | 0:51:39 | |

-watching him as they were watching a lot of people. -So we don't know? | 0:51:39 | 0:51:44 | |

But we have very good reasons to guess. | 0:51:44 | 0:51:46 | |

It turns out that the police definitely kept files | 0:51:48 | 0:51:51 | |

about Beethoven from 1815 to 1821. | 0:51:51 | 0:51:55 | |

This makes it very likely that they would have kept an eye on him | 0:51:55 | 0:51:59 | |

well before that. | 0:51:59 | 0:52:00 | |

So it's not surprising that Beethoven's letter of 1794 | 0:52:01 | 0:52:05 | |

about police arrests is his last mention of politics for a long time. | 0:52:05 | 0:52:09 | |

The glamorous city did have its dark side | 0:52:11 | 0:52:13 | |

and Beethoven clearly felt sufficiently under surveillance | 0:52:13 | 0:52:17 | |

to be careful with what he said. | 0:52:17 | 0:52:19 | |

And the bulk of what he really thought and felt | 0:52:19 | 0:52:23 | |

I think he kept for his music. | 0:52:23 | 0:52:24 | |

And Vienna was the only place to be | 0:52:38 | 0:52:40 | |

for an ambitious young composer like Beethoven. | 0:52:40 | 0:52:43 | |

It was home to the two musical giants of the age, | 0:52:43 | 0:52:46 | |

the men who Beethoven aimed to match: | 0:52:46 | 0:52:49 | |

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who'd died here in 1791, | 0:52:49 | 0:52:53 | |

and Joseph Haydn, still alive, | 0:52:53 | 0:52:55 | |

and the composer of over 100 symphonies. | 0:52:55 | 0:52:58 | |

Beethoven never held a paid post within the Imperial Court, | 0:53:00 | 0:53:03 | |

the centre of the city's music making. | 0:53:03 | 0:53:05 | |

Instead, he carved out a pioneering place | 0:53:06 | 0:53:09 | |

as a freelance composer and musician. | 0:53:09 | 0:53:11 | |

So without having a salaried position, | 0:53:13 | 0:53:17 | |

Beethoven needed to find an alternative source of income | 0:53:17 | 0:53:20 | |

while he composed. | 0:53:20 | 0:53:21 | |

Fortunately, there were plenty of opportunities | 0:53:21 | 0:53:24 | |

for the ambitious musician to gain patronage from Vienna's aristocrats. | 0:53:24 | 0:53:29 | |

Unfortunately, Beethoven had very mixed feelings | 0:53:32 | 0:53:34 | |

about being dependent on the upper classes. | 0:53:34 | 0:53:37 | |

And he had a patchy record with the Viennese rules of social etiquette. | 0:53:39 | 0:53:43 | |

One upper-class lady noted sniffily | 0:53:43 | 0:53:45 | |

that while Haydn would arrive "most carefully attired", | 0:53:45 | 0:53:49 | |

Beethoven came "negligently dressed | 0:53:49 | 0:53:51 | |

"in the freer fashion of the Upper Rhine" - | 0:53:51 | 0:53:55 | |

in other words, scruffy. | 0:53:55 | 0:53:57 | |

Tell me where we are. | 0:53:59 | 0:54:01 | |

This is the town palace of Prince Lobkowitz and his wife. | 0:54:01 | 0:54:05 | |

Concerts were the main purpose of this room, | 0:54:05 | 0:54:08 | |

because they had a private concert every week. | 0:54:08 | 0:54:12 | |

-That's him, is it? -Yeah, yeah. | 0:54:12 | 0:54:15 | |

The young and very ambitious nobility of the time, | 0:54:15 | 0:54:20 | |

they wanted, really... There was a fun factor to it. | 0:54:20 | 0:54:24 | |

They invested in a guy who did good music, | 0:54:24 | 0:54:27 | |

it was like the rock concerts of the time. | 0:54:27 | 0:54:32 | |

I mean, you had brilliant new music, a very bizarre style - | 0:54:32 | 0:54:37 | |

they were really lifted up by this kind of new experience. | 0:54:37 | 0:54:43 | |

About 80% of his compositions are dedicated to noblemen. | 0:54:43 | 0:54:48 | |

And it's because he was very into, um... | 0:54:48 | 0:54:55 | |

-Um... -Being paid? | 0:54:55 | 0:54:57 | |

..being paid and he networked very, very well | 0:54:57 | 0:55:01 | |

and he was working very hard on that. | 0:55:01 | 0:55:03 | |

Do you think he found that annoying? | 0:55:03 | 0:55:05 | |

That he needed patrons? | 0:55:05 | 0:55:07 | |

What I think is that it was too much for him. | 0:55:07 | 0:55:11 | |

For example, his relationship with another patron, | 0:55:11 | 0:55:13 | |

Prince Lichnowsky, who wanted him to eat with him. | 0:55:13 | 0:55:17 | |

Well, regularly at four o'clock in the afternoon, yes, we know that. | 0:55:19 | 0:55:23 | |

And he sometimes refused that. | 0:55:23 | 0:55:25 | |

He was older than Beethoven, about 17 years older. | 0:55:26 | 0:55:29 | |

-Yes, he looks grander. -Yes, he was already a patron of Mozart. | 0:55:29 | 0:55:32 | |

I mean, he allowed Beethoven in his house, | 0:55:32 | 0:55:35 | |

but he was with all the other servants at the beginning, | 0:55:35 | 0:55:38 | |

he was in not very agreeable rooms, and then he... | 0:55:38 | 0:55:42 | |

-He became his equal through his own talent? -Yes. | 0:55:42 | 0:55:46 | |

Then they would dine once in a while together. | 0:55:46 | 0:55:50 | |

And then the situation changed again, | 0:55:50 | 0:55:53 | |

that Beethoven sometimes said, "Oh, no, please, | 0:55:53 | 0:55:55 | |

"I just can't deal with it any more." | 0:55:55 | 0:55:57 | |

So, Beethoven can't do small talk, he doesn't dress properly, | 0:55:57 | 0:56:00 | |

he doesn't turn up to dinner when you ask him. | 0:56:00 | 0:56:03 | |

Why did everyone put up with him? | 0:56:03 | 0:56:04 | |

Because he was a brilliant composer. | 0:56:04 | 0:56:07 | |

They just loved his music. | 0:56:07 | 0:56:08 | |

I'm getting a clear picture of a man whose attitude to Viennese society | 0:56:11 | 0:56:15 | |

was complex and conflicted. | 0:56:15 | 0:56:18 | |

On the one hand, he was genuinely fond of his patrons, | 0:56:18 | 0:56:22 | |

but on the other, he was a meritocrat | 0:56:22 | 0:56:24 | |

working in an aristocratic system. | 0:56:24 | 0:56:27 | |

He famously wrote to Prince Lichnowsky: | 0:56:27 | 0:56:30 | |

"what you are, you are by accident of birth. | 0:56:30 | 0:56:34 | |

"What I am, I am by myself. | 0:56:34 | 0:56:37 | |

"There are, and will be, a thousand princes. | 0:56:37 | 0:56:40 | |

"There is only one Beethoven." | 0:56:40 | 0:56:42 | |

Is this just egotistical, | 0:56:43 | 0:56:45 | |

or is this evidence of the old, firebrand radical | 0:56:45 | 0:56:49 | |

still in there somewhere? | 0:56:49 | 0:56:50 | |

But his patrons' generosity paid for Beethoven to compose | 0:56:53 | 0:56:57 | |

and by the early 1800s, | 0:56:57 | 0:56:59 | |

he had written concertos, sonatas and his first two symphonies. | 0:56:59 | 0:57:03 | |

To boost his income, | 0:57:03 | 0:57:04 | |

Beethoven taught piano to young upper-class women. | 0:57:04 | 0:57:08 | |

There was something of a love-hate relationship here too. | 0:57:08 | 0:57:12 | |

He hated teaching, but he needed the money. | 0:57:14 | 0:57:16 | |

One can imagine in that confined situation, | 0:57:16 | 0:57:18 | |

sitting next to a young attractive woman, and that's where most often | 0:57:18 | 0:57:22 | |

he fell in love and, of course, he fell in love frequently. | 0:57:22 | 0:57:25 | |

One failed infatuation led to Beethoven's famous piano piece, | 0:57:28 | 0:57:32 | |

the Moonlight Sonata. | 0:57:32 | 0:57:34 | |

MUSIC: Moonlight Sonata | 0:57:34 | 0:57:37 | |

Indeed, his finest work often arose from personal crisis. | 0:57:37 | 0:57:40 | |

In 1802 came the most devastating of all: | 0:57:40 | 0:57:44 | |

Beethoven accepted that his hearing loss was probably untreatable. | 0:57:44 | 0:57:49 | |

He would go deaf. | 0:57:49 | 0:57:51 | |

Many believe this is "fate knocking at the door", | 0:57:51 | 0:57:53 | |

the secret behind the four-note motif at the Fifth Symphony's heart. | 0:57:53 | 0:57:57 | |

But not everyone agrees. | 0:57:59 | 0:58:01 | |

He sits down at his table in this cottage, | 0:58:01 | 0:58:04 | |

I imagine with a carafe of red wine there, | 0:58:04 | 0:58:07 | |

knocks it back to give himself strength | 0:58:07 | 0:58:09 | |

and writes his last will and testament. | 0:58:09 | 0:58:12 | |

And I imagine him staring at the paper before he writes the words. | 0:58:12 | 0:58:16 | |

He writes, "Ich bin taub" - "I am deaf." | 0:58:16 | 0:58:21 | |

And he stares at those words | 0:58:21 | 0:58:22 | |

and I imagine they were leaping out at him. | 0:58:22 | 0:58:25 | |

More wine and he's admitted it to himself for the first time, | 0:58:25 | 0:58:29 | |

and so we have the famous Heiligenstadt Testament. | 0:58:29 | 0:58:33 | |

He's confronted his deafness by writing those three little words | 0:58:33 | 0:58:37 | |

and by confronting it, he's overcome it, he's beaten it | 0:58:37 | 0:58:41 | |

and he never looks back. | 0:58:41 | 0:58:42 | |

If this is right, then it seems unlikely that the Fifth | 0:58:45 | 0:58:48 | |

is merely Beethoven railing against his deafness - | 0:58:48 | 0:58:51 | |

he has already in some way come to terms with it. | 0:58:51 | 0:58:54 | |

So began what's known as Beethoven's "heroic period", | 0:58:55 | 0:58:59 | |

where the composer produced masterpiece after masterpiece, | 0:58:59 | 0:59:02 | |

the Fifth Symphony among them. | 0:59:02 | 0:59:05 | |

The outlines of many of these great works | 0:59:05 | 0:59:07 | |

can be found in one of Beethoven's musical sketchbooks, | 0:59:07 | 0:59:10 | |

called Landsberg 6. | 0:59:10 | 0:59:13 | |

This definitive edition has been put together by Professor Lewis Lockwood | 0:59:13 | 0:59:17 | |

and his colleague, Alan Gosman. | 0:59:17 | 0:59:19 | |

Now, what's in this sketchbook? | 0:59:21 | 0:59:22 | |

All the sketches for all the works | 0:59:22 | 0:59:24 | |

from very late in 1802 to the beginning of 1804. | 0:59:24 | 0:59:30 | |

Now, very late in 1802 is only a couple of months after | 0:59:30 | 0:59:33 | |

the Heiligenstadt Crisis. | 0:59:33 | 0:59:35 | |

The sketchbook reveals that Beethoven has already decided | 0:59:35 | 0:59:39 | |

on the Cherubini-inspired motif. | 0:59:39 | 0:59:41 | |

On the next page and significantly marked "symphonia", | 0:59:42 | 0:59:46 | |

so he writes them a note to say, "This is what I'm writing, | 0:59:46 | 0:59:49 | |

"I'm writing a symphony now," | 0:59:49 | 0:59:51 | |

and we find the first idea for the first movement of the Fifth Symphony | 0:59:51 | 0:59:56 | |

in what appears to be a fairly developed form | 0:59:56 | 1:00:01 | |

for the basic themes of the exposition, | 1:00:01 | 1:00:03 | |

-the first theme... -HE HUMS OPENING NOTES | 1:00:03 | 1:00:06 | |

..continuing and then the second contrasting theme, | 1:00:06 | 1:00:10 | |

-second subject... -HE HUMS NOTES | 1:00:10 | 1:00:14 | |

..et cetera. | 1:00:14 | 1:00:15 | |

The rest is not clear yet, | 1:00:15 | 1:00:17 | |

but we have the beginning of the first movement, basic ideas, | 1:00:17 | 1:00:22 | |

and then some scattered ideas for what might come next. | 1:00:22 | 1:00:25 | |

And Beethoven sketched a rough version | 1:00:26 | 1:00:29 | |

of the beginning of the third movement, the scherzo. | 1:00:29 | 1:00:32 | |

At the bottom of the page, | 1:00:32 | 1:00:34 | |

late in the sketchbook, we find some interesting new material | 1:00:34 | 1:00:38 | |

which turns out to be a primordial version of the scherzo | 1:00:38 | 1:00:41 | |

of the Fifth Symphony. | 1:00:41 | 1:00:44 | |

And that continues on the next page, | 1:00:45 | 1:00:47 | |

where the trio of that scherzo in primitive form is present. | 1:00:47 | 1:00:51 | |

We have a sort of scherzo trio idea pretty well formed. | 1:00:52 | 1:00:56 | |

Now, the third movement in a symphony | 1:00:57 | 1:00:59 | |

is normally something light - | 1:00:59 | 1:01:02 | |

a dance, a minuet, something relaxed, jolly. | 1:01:02 | 1:01:05 | |

But Beethoven had other ideas. | 1:01:05 | 1:01:08 | |

THIRD MOVEMENT IS PLAYED | 1:01:08 | 1:01:11 | |

It starts off very unconventionally as a lyrical, | 1:01:26 | 1:01:29 | |

slightly ambling figure in the cellos and basses | 1:01:29 | 1:01:32 | |

and that is just a preamble to the opening rhythm, the motto, | 1:01:32 | 1:01:37 | |

that's been there right from the start of the first movement, | 1:01:37 | 1:01:40 | |

but now given in slow, whole notes by the horns. | 1:01:40 | 1:01:44 | |

And it's such a vigorous tramp of music, | 1:02:01 | 1:02:07 | |

as though Beethoven is saying, "This is how it's going to be. | 1:02:07 | 1:02:10 | |

"This is what I really believe in." | 1:02:10 | 1:02:12 | |

And it really does feel as though humanity is on the march again here. | 1:02:15 | 1:02:18 | |

And then he does something quite extraordinary. | 1:02:34 | 1:02:37 | |

In the place of a trio - the trio is usually the kind of contrast | 1:02:37 | 1:02:40 | |

to the minuet in a Mozart or Haydn symphony - | 1:02:40 | 1:02:43 | |

he goes completely berserk, totally berserk. | 1:02:43 | 1:02:46 | |

He sets off the cellos and basses and violas. | 1:02:46 | 1:02:50 | |

HE HUMS NOTES RAPIDLY | 1:02:50 | 1:02:52 | |

And you think, "What on earth is going on here?" | 1:02:58 | 1:03:00 | |

It's as though this inexorable march of the troops going into battle | 1:03:06 | 1:03:12 | |

has suddenly been diverted by a few complete hooligans | 1:03:12 | 1:03:16 | |

who are dashing off into the undergrowth saying, | 1:03:16 | 1:03:18 | |

"No, no, no, we're not going on this route, | 1:03:18 | 1:03:20 | |

"we're going somewhere completely different." | 1:03:20 | 1:03:22 | |

It's a kind of distraction | 1:03:42 | 1:03:44 | |

and then you go back to the security of the march tune. | 1:03:44 | 1:03:48 | |

Here in the third movement, it's everybody coming together, | 1:04:07 | 1:04:11 | |

as though asserting that there is an end | 1:04:11 | 1:04:14 | |

to this long march of the symphony | 1:04:14 | 1:04:16 | |

and there will be something of a conclusion. | 1:04:16 | 1:04:20 | |

Who knows at that stage what it's going to be? | 1:04:20 | 1:04:23 | |

So the scherzo seems to be revolutionary | 1:04:40 | 1:04:42 | |

in more than just musical form. | 1:04:42 | 1:04:44 | |

Maybe Cherubini's motif here is a reminder | 1:04:44 | 1:04:47 | |

that the fight for the rights of man continued, | 1:04:47 | 1:04:50 | |

as did Beethoven's own struggles in repressive Vienna. | 1:04:50 | 1:04:53 | |

Despite the personal risks, in the late 1790s, he attended the salons | 1:04:54 | 1:04:59 | |

of the French ambassador, mixing with radicals and French musicians. | 1:04:59 | 1:05:04 | |

It's most likely here that Beethoven was first introduced | 1:05:04 | 1:05:07 | |

to the work of Cherubini and other revolutionary composers. | 1:05:07 | 1:05:11 | |

France and its republican ideals seem to have been very much | 1:05:12 | 1:05:16 | |

on Beethoven's mind in the early 1800s, too. | 1:05:16 | 1:05:20 | |

The Landsberg 6 sketchbook also contains | 1:05:20 | 1:05:23 | |

the first outlines of his only opera, Fidelio, | 1:05:23 | 1:05:26 | |

that was inspired by the fall of the Bastille prison in 1789. | 1:05:26 | 1:05:31 | |

Beethoven also wrote very detailed sketches for his third symphony, | 1:05:33 | 1:05:36 | |

the Eroica - the "heroic" symphony. | 1:05:36 | 1:05:39 | |

MUSIC: Symphony No. 3 | 1:05:39 | 1:05:42 | |

It was originally named directly after this man - Napoleon Bonaparte. | 1:05:42 | 1:05:47 | |

As a young general, Napoleon had masterminded | 1:05:47 | 1:05:50 | |

the French Revolutionary Army's military success across Europe, | 1:05:50 | 1:05:53 | |

sweeping away old regimes | 1:05:53 | 1:05:55 | |

in the name of liberty, equality and brotherhood. | 1:05:55 | 1:05:58 | |

Napoleon symbolised the triumph of the individual, | 1:06:00 | 1:06:04 | |

the obscure Corsican who came from nowhere | 1:06:04 | 1:06:06 | |

in an incredibly short period of time | 1:06:06 | 1:06:09 | |

to make himself the most important man in Europe. | 1:06:09 | 1:06:13 | |

There's obviously a degree of self-identification with Beethoven. | 1:06:13 | 1:06:16 | |

They were both self-made men, they were the same age, | 1:06:16 | 1:06:20 | |

they were even the same height. | 1:06:20 | 1:06:22 | |

But the important thing for Beethoven, | 1:06:22 | 1:06:24 | |

as with so many others at the time, | 1:06:24 | 1:06:26 | |

was that Napoleon was the new standard bearer | 1:06:26 | 1:06:30 | |

for the ideals of the Revolution. | 1:06:30 | 1:06:32 | |

But for many across Europe, | 1:06:33 | 1:06:35 | |

Napoleon was becoming a parody of all he was supposed to believe in. | 1:06:35 | 1:06:39 | |

In England, caricaturists began developing the satirical stereotype | 1:06:39 | 1:06:43 | |

of Bonaparte that has lasted up to this day. | 1:06:43 | 1:06:46 | |

And the caricaturists' main line of attack | 1:06:47 | 1:06:50 | |

is that Napoleon is very small. | 1:06:50 | 1:06:53 | |

Yes. In fact, he wasn't very small. | 1:06:53 | 1:06:55 | |

He was 5'6", which is a perfectly decent height, | 1:06:55 | 1:06:59 | |

average height for a Frenchman at the time. | 1:06:59 | 1:07:03 | |

But if you show him as very small, | 1:07:03 | 1:07:04 | |

then we don't have to be that frightened of him. | 1:07:04 | 1:07:07 | |

You also show him as evil, so we have to fight him. | 1:07:07 | 1:07:10 | |

-Small, evil person. -Small, evil person who we can overthrow, yep. | 1:07:10 | 1:07:14 | |

-So he became known as "Little Boney"? -"Little Boney", yeah. | 1:07:14 | 1:07:17 | |

And there he is. And who is this? | 1:07:17 | 1:07:18 | |

This is Marianne, the genius of France, | 1:07:18 | 1:07:21 | |

this horrible harridan, blood-soaked, of course, | 1:07:21 | 1:07:25 | |

and she is dangling him as a little child on her hand. | 1:07:25 | 1:07:28 | |

And these are... Again, he's very, very small, | 1:07:28 | 1:07:32 | |

-but these are reproduced on mugs. -These are on mugs. | 1:07:32 | 1:07:35 | |

These show what will happen if Napoleon did arrive in London | 1:07:35 | 1:07:39 | |

and he's standing outside the print shop, of course, | 1:07:39 | 1:07:43 | |

of Mr Fores in Piccadilly | 1:07:43 | 1:07:44 | |

and he's pointing to lots of prints of buildings in London | 1:07:44 | 1:07:48 | |

and he's pointing to the Bank of England | 1:07:48 | 1:07:50 | |

and saying, "Can I have that one?" | 1:07:50 | 1:07:52 | |

The huge volunteer soldier is saying, | 1:07:52 | 1:07:56 | |

-"No fear..." -"No." -"..off you go." | 1:07:56 | 1:07:58 | |

And he's at least double his size. | 1:07:58 | 1:08:01 | |

-There is no threat. -Of course, no threat. | 1:08:01 | 1:08:03 | |

Beethoven developed his own doubts. | 1:08:05 | 1:08:08 | |

As he became more powerful, | 1:08:08 | 1:08:09 | |

Napoleon had the royal Fontainebleau Palace refurbished | 1:08:09 | 1:08:14 | |

for his own personal use. | 1:08:14 | 1:08:15 | |

It's what they called, "La vie de chateau". | 1:08:17 | 1:08:21 | |

Quite agreeable, really. | 1:08:21 | 1:08:22 | |

In 1799, a coup made Napoleon France's First Consul. | 1:08:25 | 1:08:30 | |

Elections were suspended and he assumed near dictatorial powers. | 1:08:30 | 1:08:34 | |

Napoleon had this beautiful room redesigned, | 1:08:35 | 1:08:38 | |

after he had seamlessly taken over the king's old palace | 1:08:38 | 1:08:41 | |

and placed himself in it. | 1:08:41 | 1:08:43 | |

Beethoven, like many others at the time, | 1:08:43 | 1:08:45 | |

had a love-hate relationship with Napoleon, | 1:08:45 | 1:08:49 | |

wavering between admiration and disgust. | 1:08:49 | 1:08:53 | |

But he clung on to the hope that, somehow, the French leader | 1:08:55 | 1:08:58 | |

could make the ideals of the Revolution a reality. | 1:08:58 | 1:09:01 | |

In 1803, he planned on naming his third symphony | 1:09:02 | 1:09:05 | |

directly after Napoleon. | 1:09:05 | 1:09:07 | |

A friend of Beethoven's wrote, | 1:09:08 | 1:09:10 | |

"At the time, Beethoven held him in the highest esteem. | 1:09:10 | 1:09:13 | |

"I saw a copy of the score lying on his table - | 1:09:13 | 1:09:16 | |

"at the head of the title page was the word 'Bonaparte'." | 1:09:16 | 1:09:20 | |

But the final straw for Beethoven came | 1:09:23 | 1:09:25 | |

when Napoleon was crowned emperor in 1804. | 1:09:25 | 1:09:29 | |

All in the cause of revolutionary ideals, obviously... | 1:09:29 | 1:09:33 | |

Even at home at Fontainebleau, Napoleon liked to have a throne. | 1:09:36 | 1:09:41 | |

In the actual ceremony, Napoleon wasn't crowned by the Pope. | 1:09:41 | 1:09:44 | |

He took the crown from the Pope and put it on his own head. | 1:09:44 | 1:09:49 | |

And to rub salt into the wound, | 1:09:49 | 1:09:51 | |

as he did so, he swore an oath to liberty and equality. | 1:09:51 | 1:09:56 | |

It is said that when Beethoven heard this, | 1:09:56 | 1:09:58 | |

he flew into an absolute rage | 1:09:58 | 1:10:01 | |

and began a foul-mouthed rant about Napoleon. | 1:10:01 | 1:10:04 | |