Art History Primary Class Clips

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Art History. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

This is Monet's garden. | 0:00:35 | 0:00:37 | |

He's one of the world's most famous and best-loved artists, | 0:00:37 | 0:00:41 | |

and lived here for 43 years. | 0:00:41 | 0:00:44 | |

Claude Monet loved gardening, | 0:00:44 | 0:00:46 | |

As soon as he moved here in 1883, | 0:00:46 | 0:00:48 | |

he set to work transforming the grounds. | 0:00:48 | 0:00:51 | |

Monet was not only creating a beautiful garden - | 0:00:55 | 0:00:58 | |

he was composing the subject matter for many of his paintings. | 0:00:58 | 0:01:03 | |

It's amazing - with all these flowers and vibrant colours, | 0:01:03 | 0:01:07 | |

it's just like stepping into one of Monet's paintings. | 0:01:07 | 0:01:11 | |

You may recognise this pond and bridge from one of Monet's | 0:01:21 | 0:01:24 | |

famous paintings - Waterlily Pond, one of my favourites. | 0:01:24 | 0:01:28 | |

I'll try to capture it in a Monet-style painting of my own. | 0:01:28 | 0:01:32 | |

I'm doing a rough sketch to work out my basic composition. | 0:01:32 | 0:01:36 | |

The Impressionists got their name from one of Monet's early works, | 0:01:39 | 0:01:44 | |

called... | 0:01:44 | 0:01:45 | |

He captured the impression of early morning light using vague shapes | 0:01:47 | 0:01:52 | |

and concentrated on light and colour, rather than precise outline. | 0:01:52 | 0:01:56 | |

You can get the same effect by half-closing your eyes. | 0:01:56 | 0:02:01 | |

I won't squint through my painting - not very practical! | 0:02:01 | 0:02:04 | |

I've got something to look through - an old plastic folder. | 0:02:04 | 0:02:08 | |

If I hold it in front of me, it softens the hard edges, | 0:02:08 | 0:02:12 | |

so I can concentrate on the light and colour. | 0:02:12 | 0:02:15 | |

Another Impressionist technique is to use thick brush strokes. | 0:02:15 | 0:02:20 | |

Up close, they don't look much, but from a distance, look superb. | 0:02:20 | 0:02:24 | |

Given how big some of Monet's canvases were, | 0:02:24 | 0:02:27 | |

you'd HAVE to view them from a distance. | 0:02:27 | 0:02:30 | |

To create my Impressionist painting, I'm not using brushes. | 0:02:34 | 0:02:38 | |

I'm using my fingertips. | 0:02:38 | 0:02:40 | |

I'm going to start with a nice light green for the willow. | 0:02:40 | 0:02:44 | |

I'm using acrylic paint. Monet would have used oils, | 0:02:49 | 0:02:53 | |

but acrylics give the same effect and dry a lot quicker. | 0:02:53 | 0:02:57 | |

Monet believed things should be painted where they were - | 0:03:01 | 0:03:05 | |

to paint the garden, he'd stand in the garden, whether it be 3 degrees | 0:03:05 | 0:03:09 | |

or 33 degrees, like today. | 0:03:09 | 0:03:12 | |

Phew! | 0:03:13 | 0:03:14 | |

Painting here in Monet's garden, | 0:03:16 | 0:03:18 | |

I feel a little like the Great Master himself. | 0:03:18 | 0:03:21 | |

I like that. | 0:03:28 | 0:03:30 | |

This is a film about a man who became an artist because he missed a train. | 0:03:42 | 0:03:47 | |

This happened many years ago. | 0:03:47 | 0:03:49 | |

He left the station in a Manchester suburb | 0:03:49 | 0:03:52 | |

and started to walk up the road wondering what to do. | 0:03:52 | 0:03:55 | |

He came to some streets of terraced houses, | 0:03:57 | 0:03:59 | |

which lay at the foot of an immense mill. | 0:03:59 | 0:04:02 | |

As he took in the scene, he was filled with the urge to paint it. | 0:04:02 | 0:04:06 | |

And at that moment, he decided to become an artist. | 0:04:06 | 0:04:10 | |

His name is Laurence Stephen Lowry. What was there in these sooty streets | 0:04:10 | 0:04:15 | |

to make Lowry wish to spend his life amongst them, | 0:04:15 | 0:04:17 | |

painting a world in which other people could see no beauty? | 0:04:17 | 0:04:21 | |

I really don't know why I paint these streets. | 0:04:21 | 0:04:24 | |

I just paint them, that's all, as far as I can see. | 0:04:24 | 0:04:28 | |

There's something about them that attracts me in a pictorial sense. | 0:04:28 | 0:04:32 | |

But I do feel that the pictures that I like the best | 0:04:32 | 0:04:37 | |

are pictures done entirely from... call it imagination if you like. | 0:04:37 | 0:04:42 | |

I start on an empty canvas | 0:04:47 | 0:04:49 | |

and prefer to paint from the mind's eye. | 0:04:49 | 0:04:53 | |

And, er... | 0:04:53 | 0:04:56 | |

Often I haven't the slightest idea what I'm going to put on the canvas. | 0:04:56 | 0:05:01 | |

In that case, I suggest something, | 0:05:01 | 0:05:05 | |

call it a chimney or church or anything else... | 0:05:05 | 0:05:09 | |

..going along slowly and adding things | 0:05:10 | 0:05:15 | |

and, in a strange sort of a way, it seems to come. | 0:05:15 | 0:05:20 | |

I work like that until the canvas is completely filled. | 0:05:20 | 0:05:26 | |

My figures may be long and thin and their boots may be enormous, | 0:05:26 | 0:05:29 | |

but I don't mind it at all. I see them like that, | 0:05:29 | 0:05:33 | |

so I paint them like that. If they call them matchstick figures, | 0:05:33 | 0:05:36 | |

well...let them do it. I don't mind at all. | 0:05:36 | 0:05:39 | |

Of course, they're intricate pictures | 0:05:39 | 0:05:42 | |

and they're full of figures and detail. | 0:05:42 | 0:05:45 | |

It all takes balancing, which is not easy to do. | 0:05:45 | 0:05:50 | |

You work on this, as I say, not working too often, | 0:05:50 | 0:05:54 | |

or too rapidly, until I find that the time comes | 0:05:54 | 0:05:59 | |

and you can do no more with the picture. | 0:05:59 | 0:06:03 | |

When you're satisfied with that, you leave it as complete. | 0:06:03 | 0:06:07 | |

This is his actual studio, | 0:06:22 | 0:06:25 | |

just as he left it almost 100 years ago. | 0:06:25 | 0:06:29 | |

'This was where Cezanne really started to experiment | 0:06:31 | 0:06:35 | |

'using what's normally a very mundane subject - the still life. | 0:06:35 | 0:06:39 | |

'And all around his studio are the actual objects he painted.' | 0:06:41 | 0:06:46 | |

Still-lifes had traditionally been a way for an artist | 0:06:53 | 0:06:56 | |

to show how superbly realistically and perfectly they could paint. | 0:06:56 | 0:07:02 | |

But Cezanne wasn't interested in that at all. | 0:07:02 | 0:07:06 | |

He wasn't interested in a photographic likeness. | 0:07:06 | 0:07:09 | |

He was interested in a whole new way of seeing things | 0:07:09 | 0:07:13 | |

and then putting them onto his canvas. | 0:07:13 | 0:07:16 | |

I've arranged some of his objects | 0:07:17 | 0:07:20 | |

in what's a fairly pleasing shape for me, I think. | 0:07:20 | 0:07:23 | |

He never followed perspective | 0:07:23 | 0:07:26 | |

the way traditional artists saw perspective. | 0:07:26 | 0:07:30 | |

If he wanted to see into the top of a bowl, | 0:07:30 | 0:07:34 | |

he would go and prop it up with something, | 0:07:34 | 0:07:37 | |

so, instead of seeing sort of a flat bit, | 0:07:37 | 0:07:39 | |

he would tilt it up so he could see that sort of a view of it. | 0:07:39 | 0:07:43 | |

So I think I'll tilt that basket, | 0:07:43 | 0:07:46 | |

move that back here and sit the basket up there. | 0:07:46 | 0:07:50 | |

'Cezanne would spend days fine-tuning his compositions, | 0:07:50 | 0:07:54 | |

'sometimes using coins to tilt things by just the right amount. | 0:07:54 | 0:07:57 | |

'He often took so long, | 0:07:57 | 0:07:59 | |

'he had to use artificial fruit to stop the real fruit from rotting. | 0:07:59 | 0:08:04 | |

'Cezanne loved painting still-lifes. | 0:08:04 | 0:08:06 | |

'He had complete control over the arrangement | 0:08:06 | 0:08:10 | |

'and it would stay put there for months, | 0:08:10 | 0:08:12 | |

'unlike his fidgety portrait sitters. | 0:08:12 | 0:08:15 | |

'With a still life, he could do something really special, | 0:08:15 | 0:08:19 | |

'just with some plain old fruit. He even boasted | 0:08:19 | 0:08:22 | |

'that he would astonish Paris with an apple.' | 0:08:22 | 0:08:26 | |

He created the shape, the roundness, | 0:08:27 | 0:08:30 | |

by different colours, rather than by different tones. | 0:08:30 | 0:08:35 | |

He would have apples in the foreground, which we would assume | 0:08:35 | 0:08:40 | |

would be bigger than way off in the background, | 0:08:40 | 0:08:43 | |

but he ignored all that sort of perspective. | 0:08:43 | 0:08:46 | |

For example, this line of the table | 0:08:46 | 0:08:49 | |

is completely out of whack. On purpose, of course. | 0:08:49 | 0:08:52 | |

'Finally, I think I can see what Cezanne was doing | 0:08:56 | 0:09:00 | |

'and I'm really pleased with my painting.' | 0:09:00 | 0:09:03 | |

I think I've done all I can now. | 0:09:06 | 0:09:08 | |

'In Cezanne's still-life paintings, the rules of the picture | 0:09:09 | 0:09:14 | |

'were important than the rules of real life. There was nothing | 0:09:14 | 0:09:18 | |

'to stop him painting a fruit bowl all wonky if he wanted to. | 0:09:18 | 0:09:22 | |

'This was what people couldn't get their heads around, | 0:09:23 | 0:09:26 | |

'but he didn't care. He knew he was onto something.' | 0:09:26 | 0:09:30 | |

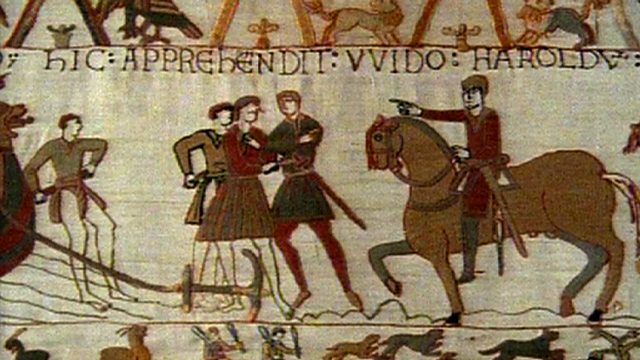

1066 is the best-known date in English history. | 0:09:39 | 0:09:42 | |

Harold, the last Anglo Saxon King of the English, | 0:09:42 | 0:09:45 | |

lost his eye to an arrow and his crown to William, Duke of Normandy, | 0:09:45 | 0:09:48 | |

at the Battle of Hastings. A great deal of what we know, | 0:09:48 | 0:09:52 | |

or think we know about the event, is captured in the Bayeux Tapestry. | 0:09:52 | 0:09:56 | |

The first thing to say about the Bayeux Tapestry | 0:09:56 | 0:09:59 | |

is that it's not a tapestry at all. Technically, it's an embroidery. | 0:09:59 | 0:10:03 | |

A tapestry is woven on the loom. | 0:10:03 | 0:10:05 | |

An embroidery is stitched onto the fabric - in this case, linen. | 0:10:05 | 0:10:10 | |

The images in the Bayeux Tapestry are terribly familiar - | 0:10:10 | 0:10:13 | |

men going like that, going overseas and meeting kings. | 0:10:13 | 0:10:17 | |

When you see it for real, it's quite a surprise just what it looks like, | 0:10:17 | 0:10:23 | |

in terms of its proportions. That's only half of it, way down there. | 0:10:23 | 0:10:27 | |

It's displayed on a U-bend on the outside of it, here in its gallery. | 0:10:27 | 0:10:31 | |

It's now accepted that the tapestry was made in England, | 0:10:31 | 0:10:34 | |

which was top nation at tapestry making at the time. | 0:10:34 | 0:10:37 | |

It was sewn by English craftsmen, but probably designed by a Norman, | 0:10:37 | 0:10:41 | |

and commissioned and paid for by William's half-brother, | 0:10:41 | 0:10:44 | |

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. | 0:10:44 | 0:10:46 | |

In the main central band, | 0:10:46 | 0:10:49 | |

there are depicted over 600 men, | 0:10:49 | 0:10:51 | |

200 horses, 50 dogs... | 0:10:51 | 0:10:54 | |

and three women. | 0:10:54 | 0:10:55 | |

Anglo-Saxons are recognised by their moustaches, | 0:11:00 | 0:11:03 | |

Normans by their hair, cropped aggressively short at the back. | 0:11:03 | 0:11:07 | |

The more you look at the tapestry, the more sophisticated it appears. | 0:11:07 | 0:11:11 | |

To take a simple example, | 0:11:11 | 0:11:13 | |

Harold is here shown eating a meal before sailing to France. | 0:11:13 | 0:11:17 | |

He and his companions are on the first floor of a large house. | 0:11:17 | 0:11:21 | |

But for economy of space in the tapestry, | 0:11:21 | 0:11:23 | |

the upper floor is also the meal table. | 0:11:23 | 0:11:26 | |

Holding up the roof on the right, | 0:11:26 | 0:11:28 | |

there is a man who points the way down the stairs to Harold, | 0:11:28 | 0:11:31 | |

who is now seen boarding his ship to Normandy. | 0:11:31 | 0:11:34 | |

Where necessary, scenes are separated by highly stylised trees. | 0:11:44 | 0:11:48 | |

In the borders, drawings of fables and fantastic beasts | 0:11:55 | 0:11:59 | |

comment on the action. | 0:11:59 | 0:12:01 | |

One or two scenes appear to be out of order, | 0:12:21 | 0:12:24 | |

and have sometimes been dismissed as mistakes. | 0:12:24 | 0:12:26 | |

But the ordering is no more an accident | 0:12:26 | 0:12:29 | |

than is the use of flashback in a novel or a feature film. | 0:12:29 | 0:12:32 | |

Westminster Abbey, Edward the Confessor's burial place, | 0:12:32 | 0:12:35 | |

is shown before his funeral procession | 0:12:35 | 0:12:38 | |

and two-layered deathbed scene. | 0:12:38 | 0:12:40 | |

This is not because the designer forgot that you do not bury a king | 0:12:40 | 0:12:44 | |

before he dies. Rather, it's done in this way | 0:12:44 | 0:12:46 | |

so that the man offering the crown to Harold in the next scene | 0:12:46 | 0:12:50 | |

can point to Edward, bequeathing him the kingdom just before his death. | 0:12:50 | 0:12:53 | |

What everyone knows - or thinks they know - about the Battle of Hastings | 0:12:53 | 0:12:57 | |

is that Harold was killed with an arrow in his eye. | 0:12:57 | 0:13:00 | |

Is the tapestry the original source of that story? | 0:13:00 | 0:13:03 | |

It's the earliest known source of the story, but it's a very plausible one. | 0:13:03 | 0:13:08 | |

And although, sometimes, people have thought that the arrow in the eye | 0:13:08 | 0:13:13 | |

was part of a restoration and wasn't in the original, | 0:13:13 | 0:13:16 | |

the stitch-holes at the back of the tapestry show clearly | 0:13:16 | 0:13:19 | |

that it WAS in the original. And as I said, it really is quite plausible, | 0:13:19 | 0:13:23 | |

because so many arrows were flying around. | 0:13:23 | 0:13:26 | |

Of course, further along, there's another man falling down, | 0:13:26 | 0:13:29 | |

obviously dead. THAT could be Harold. | 0:13:29 | 0:13:32 | |

The most plausible explanation is that they're both Harold, | 0:13:32 | 0:13:35 | |

because these are two scenes shown as in a cartoon, where you have to | 0:13:35 | 0:13:38 | |

draw your figure several times, in order to show the change. | 0:13:38 | 0:13:42 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:13:47 | 0:13:50 | |

E-mail [email protected] | 0:13:50 | 0:13:53 |