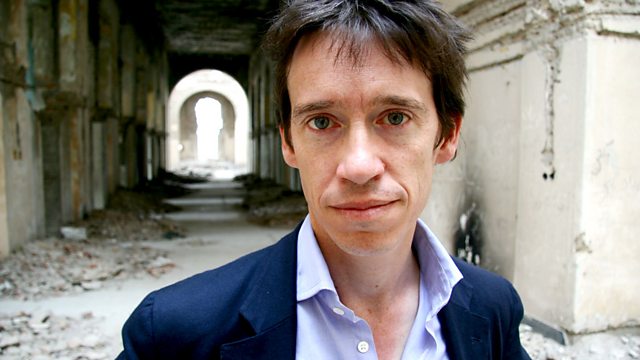

Episode 1 Afghanistan: The Great Game - A Personal View by Rory Stewart

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Episode 1. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Afghanistan - one of the most isolated, | 0:00:06 | 0:00:09 | |

barren landscapes on Earth. | 0:00:09 | 0:00:12 | |

It's difficult to believe that any empire would want to invade it, | 0:00:12 | 0:00:17 | |

and yet it's become the unlikely target, | 0:00:17 | 0:00:20 | |

and obsession of some of the world's greatest empires and superpowers. | 0:00:20 | 0:00:25 | |

In 1839, up these city walls above Kabul, | 0:00:27 | 0:00:31 | |

marched red-coated veterans of Waterloo. | 0:00:31 | 0:00:35 | |

In 1879, Highlanders charged to the sound of the bagpipes. | 0:00:35 | 0:00:41 | |

In 1979, Russian special forces | 0:00:41 | 0:00:44 | |

swooped over these hills in their helicopters. | 0:00:44 | 0:00:48 | |

And in 2001, an American-led coalition invaded Afghanistan. | 0:00:48 | 0:00:54 | |

Each of these invasions has ended in tragedy and humiliation, | 0:00:55 | 0:00:59 | |

and each has sparked a fierce Afghan resistance. | 0:00:59 | 0:01:03 | |

We have never, ever liked to be conquered. | 0:01:04 | 0:01:08 | |

It's really easy to get into Afghanistan. | 0:01:08 | 0:01:10 | |

It's just the getting-out part that is very difficult. | 0:01:10 | 0:01:13 | |

Don't go into Afghanistan and get, whatever you do, | 0:01:13 | 0:01:17 | |

involved in a tribal war. | 0:01:17 | 0:01:19 | |

HE CHANTS | 0:01:19 | 0:01:22 | |

Starting with the British invasions of the 19th century, | 0:01:22 | 0:01:25 | |

how has this history forged the Afghanistan of today? | 0:01:25 | 0:01:28 | |

And what is it about this place | 0:01:28 | 0:01:30 | |

and the paranoia and aggression of empires | 0:01:30 | 0:01:34 | |

that has created repeated tragedy? | 0:01:34 | 0:01:38 | |

In these two films, I want to explore what dragged | 0:01:38 | 0:01:41 | |

these great nations into Afghanistan, | 0:01:41 | 0:01:44 | |

and why they found it so difficult to leave. | 0:01:44 | 0:01:48 | |

To sense some of the complexity of the Afghanistan that Victorian Britain chose to invade, | 0:02:06 | 0:02:12 | |

you don't even need to leave contemporary London. | 0:02:12 | 0:02:15 | |

I've come to Ealing for an evening of Afghan food, music and traditional costume | 0:02:15 | 0:02:20 | |

with a group of Afghans now resident here in west London. | 0:02:20 | 0:02:24 | |

HE GREETS THEM IN THEIR LANGUAGE | 0:02:24 | 0:02:26 | |

'In this room, a dizzying array of ethnic groups, | 0:02:28 | 0:02:31 | |

'Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara, | 0:02:31 | 0:02:35 | |

'Turkmen, Nuristani, all Afghans, | 0:02:35 | 0:02:38 | |

'and all holding different religious and political views.' | 0:02:38 | 0:02:42 | |

The divisions and consequences of war have led to more than | 0:02:45 | 0:02:49 | |

five million Afghans fleeing their country since the 1980s. | 0:02:49 | 0:02:53 | |

Do you think, for example, Britain should remain in Helmand? | 0:02:53 | 0:02:57 | |

Until they will have the infrastructure in the proper way, | 0:02:57 | 0:03:01 | |

I think they should remain. | 0:03:01 | 0:03:03 | |

-You don't think the British should remain in Helmand? -Absolutely not. | 0:03:03 | 0:03:07 | |

The microcosm of Afghanistan is there in that room, | 0:03:08 | 0:03:12 | |

and some of these people are now sitting down together round a table, | 0:03:12 | 0:03:16 | |

and in those histories and the suspicions of who joined the jihad, | 0:03:16 | 0:03:20 | |

who came from which ethnic group, | 0:03:20 | 0:03:22 | |

are many of the fissures that continue to haunt Afghanistan today. | 0:03:22 | 0:03:26 | |

And all this complexity and Afghan history, both ancient and modern, | 0:03:26 | 0:03:31 | |

so difficult to understand, | 0:03:31 | 0:03:33 | |

so often overlooked, still matters deeply for all of us today. | 0:03:33 | 0:03:38 | |

And it continues to preoccupy commentators, | 0:03:38 | 0:03:41 | |

such as Akbar Ahmed, who I've come to meet here in Washington DC. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:46 | |

Professor Ahmed, a Pakistani who once worked as an administrator | 0:03:46 | 0:03:49 | |

on the North-West Frontier with Afghanistan, | 0:03:49 | 0:03:52 | |

arrived in the States where he now teaches, | 0:03:52 | 0:03:54 | |

a day before the World Trade Center attack. | 0:03:54 | 0:03:57 | |

But his direct appeal to the White House for caution fell on deaf ears. | 0:03:57 | 0:04:02 | |

I think on 9/11 the US administration had no idea about Afghanistan, | 0:04:05 | 0:04:10 | |

its tribes, its history, | 0:04:10 | 0:04:13 | |

but it was so motivated, so intensely motivated | 0:04:13 | 0:04:18 | |

by a sense of anger, a sense of revenge, a sense of honour, | 0:04:18 | 0:04:22 | |

that, at all costs, it had to rush into Afghanistan. | 0:04:22 | 0:04:26 | |

I said many, many superpowers have gone charging into Afghanistan. | 0:04:26 | 0:04:31 | |

Be very careful. | 0:04:31 | 0:04:32 | |

And that is the big problem, that when you combine arrogance | 0:04:32 | 0:04:36 | |

with a lack of knowledge of that part of the world, | 0:04:36 | 0:04:39 | |

you are almost guaranteed to run into trouble. | 0:04:39 | 0:04:42 | |

I sensed this tension myself when I walked across Afghanistan shortly after 9/11. | 0:04:42 | 0:04:47 | |

I found a hospitable and attractive country | 0:04:47 | 0:04:51 | |

but still deeply conservative, | 0:04:51 | 0:04:53 | |

isolated and difficult for a foreigner to understand. | 0:04:53 | 0:04:57 | |

It made me reflect on the superpowers who have | 0:04:57 | 0:05:00 | |

so often invaded the mountains of Afghanistan, | 0:05:00 | 0:05:03 | |

how often they get caught up in their own strategic games, | 0:05:03 | 0:05:07 | |

how easily they become out of touch, | 0:05:07 | 0:05:09 | |

failing to grasp the complexity and resistance of Afghanistan. | 0:05:09 | 0:05:13 | |

And I felt the same was true for the British in the 19th century. | 0:05:14 | 0:05:18 | |

When they came, they were focused not on Afghanistan itself, but its neighbours. | 0:05:18 | 0:05:23 | |

If I were a British Redcoat standing on this wall in 1839, | 0:05:23 | 0:05:27 | |

I would have been told that the reason I was here was that | 0:05:27 | 0:05:31 | |

British India lay to the east and Russia lay to the north, | 0:05:31 | 0:05:35 | |

and Afghanistan was trapped between two expanding empires. | 0:05:35 | 0:05:39 | |

Afghanistan, a largely barren country, but with a rich Islamic civilisation, | 0:05:42 | 0:05:48 | |

had long fought and traded with its Muslim and Asian neighbours, | 0:05:48 | 0:05:52 | |

but it had never encountered | 0:05:52 | 0:05:54 | |

a non-Muslim power as alien as Britain. | 0:05:54 | 0:05:57 | |

And yet, in the 1830s, | 0:05:57 | 0:05:59 | |

Afghanistan was perceived, as it is believed to be today, | 0:05:59 | 0:06:02 | |

to be an immediate threat to British national security, | 0:06:02 | 0:06:07 | |

a place for the politicians and generals of empire to fret about. | 0:06:07 | 0:06:12 | |

For hundreds of years, | 0:06:14 | 0:06:16 | |

all the conflicts had happened here in Europe | 0:06:16 | 0:06:19 | |

and suddenly it exploded east. | 0:06:19 | 0:06:22 | |

Russia raced towards Japan, Britain came into India, | 0:06:22 | 0:06:27 | |

and as these great empires expanded, | 0:06:27 | 0:06:29 | |

there was this zone in between, | 0:06:29 | 0:06:31 | |

almost a blank space on the map with very, very few towns, | 0:06:31 | 0:06:35 | |

a place of deserts and mountains. | 0:06:35 | 0:06:39 | |

And although these two empires were still 4,000 miles apart, | 0:06:39 | 0:06:43 | |

they were certain that they were about to meet. | 0:06:43 | 0:06:46 | |

They were going meet here, in Afghanistan. | 0:06:46 | 0:06:49 | |

As Britain and Russia stretched and flexed, Afghanistan, | 0:06:56 | 0:07:00 | |

one of the most remote and impoverished kingdoms in the world, | 0:07:00 | 0:07:04 | |

found itself sandwiched between two empires who both claimed, | 0:07:04 | 0:07:08 | |

at least, to be its friend. | 0:07:08 | 0:07:10 | |

Britain feared Russia might creep south towards British-ruled India, | 0:07:11 | 0:07:15 | |

the jewel in the crown of the Empire, and the second centre of British political power. | 0:07:15 | 0:07:21 | |

But suspicions worked both ways. | 0:07:21 | 0:07:24 | |

The Russians were equally nervous | 0:07:24 | 0:07:26 | |

about Britain moving north from its base in India. | 0:07:26 | 0:07:28 | |

Sensing that these two empires would collide in Afghanistan, | 0:07:35 | 0:07:39 | |

the British government was hungry for intelligence on this blank space. | 0:07:39 | 0:07:44 | |

A spy was despatched. | 0:07:44 | 0:07:46 | |

Alexander Burnes, a man I believe to be one of our greatest ever political officers. | 0:07:46 | 0:07:54 | |

This is not a man actually in fancy dress. | 0:07:54 | 0:07:58 | |

He's in disguise. | 0:07:58 | 0:07:59 | |

One of dozens of British officers who made their reputations | 0:07:59 | 0:08:03 | |

doing journeys which were almost suicidal. | 0:08:03 | 0:08:07 | |

Burnes was one of the very first to study Afghanistan for British intelligence. | 0:08:09 | 0:08:14 | |

His spying mission was both extraordinary and brave. | 0:08:14 | 0:08:17 | |

In 1831, travelling undercover in disguise, | 0:08:17 | 0:08:21 | |

he surveyed the route all the way from India through Kabul to Bukhara, | 0:08:21 | 0:08:27 | |

and produced the first detailed accounts of Afghan politics. | 0:08:27 | 0:08:31 | |

He set off with no protection into one of the most dangerous | 0:08:31 | 0:08:35 | |

and unknown parts of Asia, | 0:08:35 | 0:08:36 | |

a place where his predecessors had been killed, | 0:08:36 | 0:08:39 | |

where he was having to run the gauntlet of slave traders, | 0:08:39 | 0:08:43 | |

where he was a Christian moving through some regions which were fanatically Muslim | 0:08:43 | 0:08:47 | |

and which were famous for killing infidels. | 0:08:47 | 0:08:49 | |

Trying to rely all the way not on his sword but, as he says in a letter to his mother - | 0:08:49 | 0:08:55 | |

on his languages, on his charm, on his politeness. | 0:08:55 | 0:08:58 | |

Along with the suicidal danger of what Burnes did | 0:09:00 | 0:09:04 | |

was the incredible reward because, when he returned back to London having completed this journey, | 0:09:04 | 0:09:10 | |

this nearly 12-month journey through largely unknown country, | 0:09:10 | 0:09:14 | |

he was a massive celebrity. | 0:09:14 | 0:09:17 | |

He returned 28 years old, had an audience with the king, | 0:09:17 | 0:09:20 | |

was made a member of the Athenian Club, | 0:09:20 | 0:09:22 | |

got a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society. | 0:09:22 | 0:09:25 | |

And the book Burnes wrote, Travels To Bukhara, | 0:09:27 | 0:09:30 | |

became an overnight bestseller. | 0:09:30 | 0:09:32 | |

But, although it gave Britain a unique insight into this largely unknown land, | 0:09:32 | 0:09:37 | |

according to historian William Dalrymple, his visit also terrified the Russians | 0:09:37 | 0:09:42 | |

and had an unanticipated, counterproductive effect. | 0:09:42 | 0:09:47 | |

There are British agents in Central Asia long before the Russians | 0:09:47 | 0:09:51 | |

had taken any interest in cities like Bukhara and Khiva. | 0:09:51 | 0:09:54 | |

And it's only when Burnes' travel book Journeys Into Bukhara | 0:09:54 | 0:09:57 | |

is translated into French and becomes widely read in Moscow, | 0:09:57 | 0:10:01 | |

that the Russians think they should send an agent in | 0:10:01 | 0:10:05 | |

to make sure the British are not manoeuvring | 0:10:05 | 0:10:08 | |

and making plots in their backyard. | 0:10:08 | 0:10:11 | |

Shortly after Burnes was sent back to Kabul in 1836, | 0:10:14 | 0:10:18 | |

he spotted this Russian agent, Jan Vitkevich, | 0:10:18 | 0:10:21 | |

and the Russian's arrival terrified the British. | 0:10:21 | 0:10:24 | |

They became, in turn, very suspicious | 0:10:24 | 0:10:26 | |

of Russia's ambitions in the country. | 0:10:26 | 0:10:30 | |

And this mutual paranoia led to more and more | 0:10:30 | 0:10:33 | |

foreign intelligence operations around Afghanistan, | 0:10:33 | 0:10:37 | |

with rival officers like Vitkevich and Burnes sending back | 0:10:37 | 0:10:42 | |

countless reports on each other's activities. | 0:10:42 | 0:10:45 | |

The Russians called it The Tournament of Shadows. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:51 | |

The British now remember it, thanks to Rudyard Kipling's later writing, | 0:10:51 | 0:10:56 | |

as The Great Game. | 0:10:56 | 0:10:59 | |

One of my favourite books is Kipling's Kim, | 0:11:01 | 0:11:05 | |

which describes The Great Game through the eyes of this young English boy, | 0:11:05 | 0:11:09 | |

who's working on the North-West Frontier as a spy. | 0:11:09 | 0:11:12 | |

It's incredibly dangerous work, his intrigues with the Russians. | 0:11:12 | 0:11:16 | |

He's a secret agent, he's deniable, | 0:11:16 | 0:11:18 | |

he's at arm's length from the British government. | 0:11:18 | 0:11:21 | |

But, of course, this was a game that had two teams and on the other side, | 0:11:21 | 0:11:26 | |

the Russians, men like Vitkevich, travelling into Kabul, | 0:11:26 | 0:11:31 | |

developing relationships with the Afghan king, | 0:11:31 | 0:11:34 | |

returning with his own documents and maps, | 0:11:34 | 0:11:36 | |

the beginning of a whole tradition, | 0:11:36 | 0:11:38 | |

whereby whenever the British saw a Russian painter turn up in the city, | 0:11:38 | 0:11:43 | |

a Russian hunter turn up on the frontier, | 0:11:43 | 0:11:45 | |

they would immediately assume that this was a double game of espionage. | 0:11:45 | 0:11:50 | |

It was all these fears and suspicions of empire | 0:11:50 | 0:11:53 | |

that were to turn Afghanistan into a battleground, | 0:11:53 | 0:11:56 | |

according to Britain's former ambassador to Moscow, | 0:11:56 | 0:12:00 | |

historian Sir Rodric Braithwaite. | 0:12:00 | 0:12:02 | |

They thought that the Russians are getting their agents into Kabul and we must forestall them. | 0:12:02 | 0:12:08 | |

We've got to do something here, with these Russians allegedly coming over the frontiers. | 0:12:08 | 0:12:12 | |

The Russians had a mirror image view of us. | 0:12:12 | 0:12:14 | |

They saw our agents penetrating northern Afghanistan | 0:12:14 | 0:12:18 | |

into areas of central Asia, which they thought were their interest. | 0:12:18 | 0:12:21 | |

They believed that these guys would come with propaganda, | 0:12:21 | 0:12:24 | |

Islamic propaganda, weapons, money, and stir up these places against the Russians, | 0:12:24 | 0:12:29 | |

so they were as terrified as we were. | 0:12:29 | 0:12:31 | |

By 1839, the British government was increasingly obsessed with the Russian threat. | 0:12:38 | 0:12:43 | |

Key advisers, men who'd never set foot in Afghanistan, | 0:12:45 | 0:12:50 | |

began to claim that Russia might use Afghanistan | 0:12:50 | 0:12:53 | |

as a stepping stone for the invasion of British India. | 0:12:53 | 0:12:56 | |

Britain's man on the ground in Afghanistan, Alexander Burnes, | 0:12:56 | 0:13:01 | |

thought that Afghanistan should be left well alone, | 0:13:01 | 0:13:04 | |

but a small group of policy-makers in the government of India had very different ideas. | 0:13:04 | 0:13:09 | |

They ignored Burnes completely. | 0:13:09 | 0:13:13 | |

In their minds Afghanistan was an empty failed state into which Russia would move. | 0:13:13 | 0:13:17 | |

The hawks decided the answer was regime change, | 0:13:21 | 0:13:24 | |

to topple the sitting king of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammad, | 0:13:24 | 0:13:28 | |

and replace him with their own man. | 0:13:28 | 0:13:30 | |

British intelligence felt they had the perfect candidate, | 0:13:32 | 0:13:36 | |

Shah Shuja, a man who'd been living in British India for 30 years, | 0:13:36 | 0:13:41 | |

urbane and beautifully dressed, | 0:13:41 | 0:13:43 | |

a man who could be relied upon to do Britain's bidding. | 0:13:43 | 0:13:46 | |

To justify themselves, they published a document | 0:13:48 | 0:13:51 | |

claiming that Dost Mohammad, who was trying to keep his distance | 0:13:51 | 0:13:54 | |

from both Russia and Britain, was in fact disloyal to the British | 0:13:54 | 0:13:58 | |

and represented an imminent and urgent threat to the British Empire. | 0:13:58 | 0:14:03 | |

The motives are always very mixed. | 0:14:05 | 0:14:07 | |

It's both the aggressive, expansive imperial instinct, | 0:14:07 | 0:14:10 | |

plus the terror that it's going come up against a brick wall or | 0:14:10 | 0:14:13 | |

somebody's going to come and take it all away from you. | 0:14:13 | 0:14:15 | |

And the trouble with intervention is that you may | 0:14:15 | 0:14:19 | |

or may not have identified the right target | 0:14:19 | 0:14:21 | |

but you then tend to use the wrong means for dealing with it. | 0:14:21 | 0:14:24 | |

So were the hawks right to fear Russia? | 0:14:28 | 0:14:32 | |

Here in Moscow, I've come to meet an eminent Russian historian of the period, | 0:14:32 | 0:14:37 | |

Professor Tatiana Zagarodnikova. | 0:14:37 | 0:14:40 | |

I wanted to ask her if Russia was really preparing to invade | 0:14:41 | 0:14:44 | |

Afghanistan as a bridgehead for an attack on India. | 0:14:44 | 0:14:47 | |

That was a time of colonisation of smaller, weaker states and that was a process all over the world, | 0:14:49 | 0:14:57 | |

not only in Great Britain and in Russia. | 0:14:57 | 0:15:00 | |

The same in France, | 0:15:00 | 0:15:03 | |

the same in other great powers. | 0:15:03 | 0:15:06 | |

Great Britain at that time considered every step of Russia, | 0:15:06 | 0:15:11 | |

either in Europe or in Asia, | 0:15:11 | 0:15:17 | |

and maybe even in Africa, as a Russian step towards India. | 0:15:17 | 0:15:22 | |

Everything was considered as the Russians' march to India. | 0:15:22 | 0:15:27 | |

Were the British paranoid? | 0:15:27 | 0:15:29 | |

Well it was just, to my mind, it was a game, | 0:15:29 | 0:15:33 | |

kind of making face, | 0:15:33 | 0:15:38 | |

towards audience, towards public opinion. | 0:15:38 | 0:15:40 | |

Another thing is that that was a wonderful pretext | 0:15:40 | 0:15:44 | |

in the parliament to demand more money for military purposes, | 0:15:44 | 0:15:50 | |

for keeping big armies in India, and so on. | 0:15:50 | 0:15:55 | |

The hawks were obsessed with putting their man on the throne, | 0:15:58 | 0:16:02 | |

but their belief in a Russian threat was more faith than reality. | 0:16:02 | 0:16:07 | |

The dossier was torn to pieces in the British press. | 0:16:07 | 0:16:10 | |

Everyone from the Duke of Wellington attacked the idea as madness, | 0:16:10 | 0:16:15 | |

but rather than calling off the mission, these men pushed on | 0:16:15 | 0:16:19 | |

and, within a few weeks, the Army of the Indus was marching into Afghanistan. | 0:16:19 | 0:16:25 | |

As we know in our own time, if you create a phantasm, | 0:16:25 | 0:16:29 | |

a horror figure of your own imaginings, | 0:16:29 | 0:16:31 | |

that figure can actually come into being. | 0:16:31 | 0:16:34 | |

You can imagine a threat into life. | 0:16:34 | 0:16:36 | |

Just like the neo-cons had wanted to topple Saddam Hussein long before 9/11, | 0:16:36 | 0:16:42 | |

and 9/11 gave the neo-cons the excuse they were looking for. | 0:16:42 | 0:16:46 | |

In the same way the hawks, the Russophobes, | 0:16:46 | 0:16:48 | |

in the British establishment in Simla and in Calcutta, | 0:16:48 | 0:16:51 | |

had been wanting to pre-empt the Russians in central Asia. | 0:16:51 | 0:16:54 | |

MILITARY DRUM AND PIPE MUSIC PLAYS | 0:16:54 | 0:16:56 | |

As they wound their way through the narrow passes towards Kabul, | 0:17:01 | 0:17:05 | |

the British Army were supremely confident. | 0:17:05 | 0:17:08 | |

They'd never been defeated in central Asia, | 0:17:08 | 0:17:12 | |

and many in the army were treating it as a game. | 0:17:12 | 0:17:16 | |

A lot of the young officers were behaving as though they were going on a grand picnic. | 0:17:16 | 0:17:21 | |

Their generals were enraged. | 0:17:21 | 0:17:23 | |

These 22-year-olds were travelling with camel trains, | 0:17:23 | 0:17:26 | |

piled with mess silver, with eau de cologne, with exotic wines. | 0:17:26 | 0:17:30 | |

The 16th Lancers even managed to bring their own pack of foxhounds towards Afghanistan. | 0:17:30 | 0:17:36 | |

The Army of the Indus arrived in Kabul in April 1839, | 0:17:43 | 0:17:47 | |

and as they swaggered into the city | 0:17:47 | 0:17:50 | |

they had little idea of the horrors ahead. | 0:17:50 | 0:17:54 | |

The British entered Kabul in squadrons, | 0:18:01 | 0:18:04 | |

the Royal Horse Artillery in gold, | 0:18:04 | 0:18:07 | |

the Lancers in scarlet, | 0:18:07 | 0:18:08 | |

the Dragoons in blue, | 0:18:08 | 0:18:10 | |

the ostrich feathers on the hats of the envoys, | 0:18:10 | 0:18:13 | |

with all the glory of a parade, a victory parade. | 0:18:13 | 0:18:16 | |

But around them in the crowded bazaar - blank faces, hostility, suspicion. | 0:18:16 | 0:18:22 | |

Britain had taken a decisive step | 0:18:24 | 0:18:26 | |

and placed an army of occupation in this distant and unlikely land. | 0:18:26 | 0:18:31 | |

But as the soldiers settled into life in Kabul, | 0:18:31 | 0:18:34 | |

their need for security made them live in protected compounds, | 0:18:34 | 0:18:38 | |

separate from the Afghan people, | 0:18:38 | 0:18:40 | |

and this only encouraged suspicions on both sides. | 0:18:40 | 0:18:45 | |

The English knew so little about the real life of Kabul. | 0:18:45 | 0:18:49 | |

If they came down to the city at all, | 0:18:49 | 0:18:51 | |

they travelled in armed groups, | 0:18:51 | 0:18:53 | |

seeing hostile Afghan faces, glimpses of tiny windows, | 0:18:53 | 0:18:58 | |

blank mud walls and they had very, very little idea | 0:18:58 | 0:19:02 | |

about the rich civilisation behind those doors. | 0:19:02 | 0:19:07 | |

Largely hidden from and totally misunderstood by most British troops, | 0:19:16 | 0:19:20 | |

was a culture of extraordinary richness, | 0:19:20 | 0:19:24 | |

a culture of calligraphy, | 0:19:24 | 0:19:26 | |

miniature painting and poetry, | 0:19:26 | 0:19:28 | |

with sophisticated Afghan forms of law, government and patronage. | 0:19:28 | 0:19:33 | |

The occupation dragged on | 0:19:40 | 0:19:42 | |

and the British only became more and more entrenched | 0:19:42 | 0:19:46 | |

and the Afghans began to get anxious. | 0:19:46 | 0:19:49 | |

The thing that really worried the Afghans was when | 0:19:49 | 0:19:51 | |

the women began to arrive and European babies were born, | 0:19:51 | 0:19:56 | |

that the British were here to stay. | 0:19:56 | 0:19:59 | |

The British, in the towers of their fort, | 0:20:04 | 0:20:07 | |

and the Afghans gazing back at them from their family compounds, | 0:20:07 | 0:20:11 | |

began to look at each other with deepening mistrust and incomprehension. | 0:20:11 | 0:20:16 | |

I've come to a rain-soaked Boston | 0:20:19 | 0:20:22 | |

to meet a world authority on Afghan anthropology and history, | 0:20:22 | 0:20:26 | |

Professor Tom Barfield. | 0:20:26 | 0:20:28 | |

Appropriately, I met him here in the Helmand Restaurant. | 0:20:28 | 0:20:32 | |

And I wanted ask him about some of the many differences between these cultures. | 0:20:32 | 0:20:37 | |

If you go to an Afghan feast, people are very religious, | 0:20:37 | 0:20:42 | |

but they're religious at the end of the meal. | 0:20:42 | 0:20:45 | |

You thank God for having eaten a wonderful meal. | 0:20:45 | 0:20:48 | |

As one of my Afghan friends said to me, | 0:20:48 | 0:20:50 | |

"Why do you Americans pray before the meal? | 0:20:50 | 0:20:53 | |

"You haven't eaten it. You have no idea whether God deserves | 0:20:53 | 0:20:56 | |

"the praise or not, or the host." | 0:20:56 | 0:20:58 | |

But the lesson that I took from him | 0:20:58 | 0:21:01 | |

is that we foreigners are too keen to praise the fact that | 0:21:01 | 0:21:05 | |

the feast is here and the Afghans say, "There's one more step. | 0:21:05 | 0:21:09 | |

"Let's eat the feast and decide whether it deserves it." | 0:21:09 | 0:21:13 | |

So the Afghans tend to look more at the outcome, than at the intentions. | 0:21:13 | 0:21:17 | |

'And that logic appears to apply | 0:21:17 | 0:21:20 | |

'to how Afghans choose the perfect leader.' | 0:21:20 | 0:21:23 | |

The ideal ruler says to the Afghans that, | 0:21:23 | 0:21:28 | |

"Without me, these foreigners would invade and occupy our country. | 0:21:28 | 0:21:32 | |

"Without me and my skill, | 0:21:32 | 0:21:35 | |

"Afghanistan would not be independent. | 0:21:35 | 0:21:38 | |

"I am defending a Muslim nation." | 0:21:38 | 0:21:41 | |

At the same time, he turns to the foreigners and says, | 0:21:41 | 0:21:44 | |

"Only I can keep control of the Afghans and I can only do that if you send me money and weapons." | 0:21:44 | 0:21:50 | |

By 1841, Britain's choice of ruler had proved a disaster. | 0:21:50 | 0:21:56 | |

Once Shah Shuja was on the throne, Afghans quickly saw him as weak, | 0:21:56 | 0:22:00 | |

as corrupt and, worst of all, | 0:22:00 | 0:22:03 | |

as a puppet of a foreign non-Muslim government. | 0:22:03 | 0:22:07 | |

In a courtyard in Kabul, I asked Afghan academic Omar Sharifi | 0:22:07 | 0:22:11 | |

about how Afghans perceived Shah Shuja. | 0:22:11 | 0:22:15 | |

If you were an Afghan seeing a red-coated British soldier in the street, | 0:22:48 | 0:22:52 | |

what would your reaction be? | 0:22:52 | 0:22:54 | |

Nobody really knew what was happening in Afghanistan. | 0:23:15 | 0:23:18 | |

Optimistic British officers felt that with a bit more time, | 0:23:18 | 0:23:21 | |

and a bit more money, they were going to be able to win. | 0:23:21 | 0:23:23 | |

And, suddenly, when rumours began to spread | 0:23:23 | 0:23:26 | |

through the tea houses and the bazaars | 0:23:26 | 0:23:28 | |

that British officers were interfering with Afghan women, | 0:23:28 | 0:23:31 | |

a match had been lit, which would spark an insurgency. | 0:23:31 | 0:23:35 | |

Suddenly, up and down the country, | 0:23:35 | 0:23:37 | |

Afghans began to feel that their culture had been insulted, | 0:23:37 | 0:23:41 | |

that their king was only a puppet, | 0:23:41 | 0:23:42 | |

and that they needed to fight for Afghanistan | 0:23:42 | 0:23:45 | |

and for Islam against a foreign military occupation. | 0:23:45 | 0:23:49 | |

Dost Mohammad, the emir the British had deposed | 0:24:00 | 0:24:03 | |

to make way for Shah Shuja, was in exile. | 0:24:03 | 0:24:06 | |

But he and his family used the presence of non-Muslim occupiers | 0:24:06 | 0:24:11 | |

to mobilise Afghans by calling for a jihad. | 0:24:11 | 0:24:15 | |

And for many Afghans, this action was | 0:24:15 | 0:24:18 | |

the birth of the modern state of Afghanistan, | 0:24:18 | 0:24:22 | |

the moment around which they united as a nation. | 0:24:22 | 0:24:25 | |

By November 1841, | 0:24:25 | 0:24:27 | |

Muslims in Kabul were ready to join this jihad. | 0:24:27 | 0:24:31 | |

But the British were taken completely by surprise. | 0:24:31 | 0:24:35 | |

Even Alexander Burnes, our envoy so prized for his local knowledge, | 0:24:35 | 0:24:39 | |

completely underestimated how dangerous the situation had become. | 0:24:39 | 0:24:44 | |

Alexander Burnes loved Kabul and Afghan culture. | 0:24:45 | 0:24:48 | |

He was used to walking through the streets as though he was at home in Scotland. | 0:24:48 | 0:24:52 | |

If you'd asked him, he would have said he could have trusted Afghans with his life. | 0:24:52 | 0:24:57 | |

But on that night in November 1841, | 0:24:57 | 0:25:01 | |

he walked home to a city that had changed. | 0:25:01 | 0:25:04 | |

He looked into eyes that no longer greeted him | 0:25:04 | 0:25:08 | |

and, as he made his way back through the narrow streets towards his house, | 0:25:08 | 0:25:13 | |

he was seeing a hostility that he hadn't sensed before. | 0:25:13 | 0:25:16 | |

By dusk, an armed mob had surrounded his house. | 0:25:18 | 0:25:23 | |

In one last attempt, he walked out onto the balcony of his house | 0:25:24 | 0:25:28 | |

and in his most confident manner, in beautiful Persian, | 0:25:28 | 0:25:31 | |

appealed to their sense of hospitality, of generosity, | 0:25:31 | 0:25:35 | |

their treatment of a guest. | 0:25:35 | 0:25:37 | |

But he got nothing back and, in the end, | 0:25:39 | 0:25:42 | |

he had to send a desperate message to the British garrison asking for help, | 0:25:42 | 0:25:48 | |

and, for the first time, retreated back into his house knowing that | 0:25:48 | 0:25:52 | |

the only thing that stood between him and death were the gates of his house. | 0:25:52 | 0:25:56 | |

Burnes' home, his paradise where he'd entertained for so long, | 0:26:07 | 0:26:11 | |

the Kabul that he loved, had become a death trap. | 0:26:11 | 0:26:15 | |

Burnes' last glimpse of a city that he loved | 0:26:20 | 0:26:22 | |

and thought the most beautiful in the world was not of gardens, | 0:26:22 | 0:26:26 | |

not of poetry, but a last desperate sprint across his neighbours' roofs | 0:26:26 | 0:26:30 | |

hoping that he could find a way out, but the crowd was everywhere. | 0:26:30 | 0:26:34 | |

He wrapped a turban around his head, dropped down, | 0:26:34 | 0:26:37 | |

praying he wouldn't be recognised and for a moment he wasn't. | 0:26:37 | 0:26:40 | |

But then the cry went up - "Sikander Burnes". He was hacked down. | 0:26:40 | 0:26:44 | |

And the next morning his head was on a pole in the bazaar. | 0:26:46 | 0:26:50 | |

The day before Burnes' death, the British had been congratulating | 0:27:01 | 0:27:04 | |

themselves on the peace and tranquillity in Afghanistan. | 0:27:04 | 0:27:07 | |

The day after, everything had collapsed. | 0:27:07 | 0:27:10 | |

A British trooper came staggering into the fort | 0:27:10 | 0:27:14 | |

with five musket wounds in his body, cuts to his head and shoulders, | 0:27:14 | 0:27:17 | |

stark naked, having just escaped from the Afghan insurgents. | 0:27:17 | 0:27:21 | |

The food was lost, the ammunition was running down, | 0:27:21 | 0:27:24 | |

and within three days of Burnes' death, | 0:27:24 | 0:27:27 | |

the British generals were talking about a treaty of surrender | 0:27:27 | 0:27:32 | |

and a retreat from Kabul. | 0:27:32 | 0:27:34 | |

The British Commander, General Elphinstone, | 0:27:34 | 0:27:37 | |

tried to negotiate with the Afghans. | 0:27:37 | 0:27:39 | |

The Afghans offered him safe passage, | 0:27:39 | 0:27:42 | |

provided the British handed over their heavy weapons | 0:27:42 | 0:27:45 | |

and retreated immediately to India. | 0:27:45 | 0:27:47 | |

It must have felt like an impossible decision. | 0:27:47 | 0:27:50 | |

If the garrison tried to stay, they could starve and be wiped out. | 0:27:50 | 0:27:55 | |

But if they were to retreat, | 0:27:55 | 0:27:57 | |

could they really trust the assurances of their enemy? | 0:27:57 | 0:28:01 | |

I faced a similar dilemma on a smaller scale | 0:28:01 | 0:28:05 | |

when I was a Deputy Governor in the south of Iraq | 0:28:05 | 0:28:08 | |

after the invasion in 2004. | 0:28:08 | 0:28:10 | |

Our compound was under siege. | 0:28:10 | 0:28:12 | |

We were being attacked by Sadarist militia, | 0:28:12 | 0:28:14 | |

and their commander came to us and said that if we agreed | 0:28:14 | 0:28:18 | |

to leave our weapons and hand ourselves over to him, | 0:28:18 | 0:28:21 | |

he would take us safely out of the fort and back. | 0:28:21 | 0:28:24 | |

At the time I thought it was a trick, a trick to massacre us, | 0:28:24 | 0:28:28 | |

and I felt, again, the same thing when I read this history. | 0:28:28 | 0:28:32 | |

In Iraq, we stayed and defended the compound, | 0:28:32 | 0:28:36 | |

but the British in Kabul, in 1841, were deeply divided. | 0:28:36 | 0:28:40 | |

Many young officers were determined to fight on, | 0:28:41 | 0:28:44 | |

but Elphinstone overruled them and ordered a retreat. | 0:28:44 | 0:28:49 | |

All the troops, their wives and children, | 0:28:49 | 0:28:52 | |

were forced to leave the relative safety of their compound, | 0:28:52 | 0:28:55 | |

and to try and reach the British garrison in Jalalabad nine days' march east of Kabul. | 0:28:55 | 0:29:01 | |

They made painfully slow progress | 0:29:03 | 0:29:06 | |

and, after two days, this straggling column of soldiers | 0:29:06 | 0:29:09 | |

and civilians met their fate beneath this mountain. | 0:29:09 | 0:29:14 | |

This valley is the jaws of hell. | 0:29:16 | 0:29:19 | |

Into this, in mid-winter, | 0:29:19 | 0:29:21 | |

the cream of the British army marched | 0:29:21 | 0:29:24 | |

and they were treated as though they were in a slaughterhouse. | 0:29:24 | 0:29:29 | |

By the time they reached this valley, Khord Kabul, | 0:29:36 | 0:29:40 | |

they had spent two nights out in the open, in three-foot snow | 0:29:40 | 0:29:43 | |

in temperatures of minus 15 without tents, | 0:29:43 | 0:29:47 | |

waking up to discover frozen corpses around them. | 0:29:47 | 0:29:50 | |

They staggered into this valley, starving, frozen, with no supplies, | 0:29:50 | 0:29:57 | |

and 80 miles to go, and it was at that point that the attack began. | 0:29:57 | 0:30:02 | |

Behind every bolder was an Afghan with a musket taking careful aim, | 0:30:17 | 0:30:24 | |

able to pick off, individually, 3,000 people and kill them | 0:30:24 | 0:30:27 | |

as they made their way through the valley. | 0:30:27 | 0:30:30 | |

And it continued, not just for one or two miles, | 0:30:33 | 0:30:37 | |

but for five miles of a ravine. | 0:30:37 | 0:30:40 | |

By the time they reached the end of that valley, | 0:30:48 | 0:30:51 | |

90% of the British army had been extinguished. | 0:30:51 | 0:30:55 | |

A handful of soldiers managed to fight their way through, | 0:31:08 | 0:31:12 | |

but only to meet their fate later. | 0:31:12 | 0:31:14 | |

What we've got here is the last stand of the 44th Foot at Gandamak. | 0:31:14 | 0:31:20 | |

50 men make it to the village of Gandamak. | 0:31:20 | 0:31:23 | |

They stand on this low hill and they have run out of ammunition, | 0:31:23 | 0:31:26 | |

they're relying only on their bayonets. | 0:31:26 | 0:31:28 | |

And the picture we see here is half of them are dead | 0:31:28 | 0:31:31 | |

and the Pathans are about to close in | 0:31:31 | 0:31:34 | |

and end it with their swords. | 0:31:34 | 0:31:37 | |

Of the 17,000 men, women and children who'd set out nine days earlier from Kabul, | 0:31:37 | 0:31:43 | |

only one made it to the British garrison in Jalalabad. | 0:31:43 | 0:31:47 | |

One man has made it on from there, this Dr Brydon. | 0:31:47 | 0:31:51 | |

And in this picture, Dr Brydon is sitting on his old nag, | 0:31:51 | 0:31:54 | |

about to collapse and he is seen limping towards Jalalabad, | 0:31:54 | 0:31:59 | |

and they assume he's only the first of thousands of troops to make it, | 0:31:59 | 0:32:03 | |

and the gates are opened and a party sent out. | 0:32:03 | 0:32:06 | |

And they realise he's the only one. | 0:32:06 | 0:32:08 | |

And that night the commanding officer orders the bugles to be sounded all night. | 0:32:08 | 0:32:12 | |

The wind was blowing very strongly that night and, | 0:32:15 | 0:32:18 | |

rather than billowing out into the plain of Jalalabad, | 0:32:18 | 0:32:22 | |

it blew back into the town, and he said that the noise of the trumpets | 0:32:22 | 0:32:28 | |

echoing amid the wail of the wind sounded like an elegy to the dead army. | 0:32:28 | 0:32:33 | |

The British Empire never had, and never would, | 0:32:35 | 0:32:38 | |

experience a defeat like it. | 0:32:38 | 0:32:40 | |

The first Afghan war was a major event for the Afghans. | 0:32:40 | 0:32:43 | |

We always see it through our perspective as the great imperial disaster, | 0:32:43 | 0:32:47 | |

but for the Afghans, this was their Trafalgar, | 0:32:47 | 0:32:50 | |

their Battle of Britain, their Waterloo, all in one. | 0:32:50 | 0:32:54 | |

They were the only non-colonial power | 0:32:54 | 0:32:58 | |

to see off a modern westernised army in the 19th century, | 0:32:58 | 0:33:03 | |

on the sort of magnificent scale that they did, | 0:33:03 | 0:33:06 | |

and completely destroyed an entire Victorian army at the very peak of Britain's power. | 0:33:06 | 0:33:12 | |

For Afghans, this had confirmed that they were a warrior nation, | 0:33:14 | 0:33:18 | |

one even capable of seeing off a great power like Britain, | 0:33:18 | 0:33:22 | |

but Western historians point to another legacy that resonates today. | 0:33:22 | 0:33:26 | |

The first time there's really a feeling of jihad inside Afghanistan | 0:33:27 | 0:33:31 | |

is the first Anglo-Afghan war. | 0:33:31 | 0:33:33 | |

After that, it never really goes away. | 0:33:33 | 0:33:36 | |

Beginning with the British invasions, | 0:33:36 | 0:33:38 | |

Afghans begin to perceive themselves as fighting an outside non-Muslim world. | 0:33:38 | 0:33:44 | |

Now, they had known this before. | 0:33:44 | 0:33:46 | |

When they raided India, that was jihad, you know. | 0:33:46 | 0:33:48 | |

You got to go into infidel lands and take home a lot of good stuff. | 0:33:48 | 0:33:53 | |

But inside Afghanistan, you couldn't do jihad. | 0:33:53 | 0:33:56 | |

Now when these foreigners invaded, people would say, "Yes, we're fighting non-Muslims." | 0:33:56 | 0:34:00 | |

The British government would have liked to cover up | 0:34:03 | 0:34:06 | |

the extent of this tragedy, but it was not to be. | 0:34:06 | 0:34:09 | |

Almost every last grisly detail was immortalised | 0:34:09 | 0:34:13 | |

in the bestselling diaries of Lady Sale, | 0:34:13 | 0:34:15 | |

wife of one of the senior officers in the Kabul Army. | 0:34:15 | 0:34:19 | |

She was captured during the retreat and later released, | 0:34:19 | 0:34:24 | |

and her original diaries and letters are kept here in the British Library. | 0:34:24 | 0:34:28 | |

I took a look at them with historian Jane Robinson. | 0:34:28 | 0:34:34 | |

Well, the book ran into several reprints in the first couple of years. | 0:34:34 | 0:34:38 | |

It sold 7,500 copies, which was huge, and it was serialised in The Times. | 0:34:38 | 0:34:43 | |

And the response to it was unprecedented, I think, | 0:34:43 | 0:34:46 | |

because this was the first time that a woman, a British woman, | 0:34:46 | 0:34:50 | |

had written from the theatre of war. | 0:34:50 | 0:34:52 | |

Lady Sale's account of the retreat from Kabul was shockingly explicit. | 0:34:53 | 0:34:59 | |

To see women and children and soldiers and camp followers | 0:34:59 | 0:35:02 | |

in various states of decomposition, | 0:35:02 | 0:35:04 | |

and she actually describes it... | 0:35:04 | 0:35:07 | |

I see here that some of the text has been excised, | 0:35:07 | 0:35:10 | |

I think as possibly being too strong. | 0:35:10 | 0:35:12 | |

This was horrific stuff. | 0:35:12 | 0:35:14 | |

"Subsequently we heard that scarcely any of these poor wretches escaped | 0:35:14 | 0:35:18 | |

"and that, driven to the extreme of hunger, | 0:35:18 | 0:35:20 | |

"they'd sustained life by feeding on their dead comrades." | 0:35:20 | 0:35:25 | |

And she knew that the army was doomed. | 0:35:25 | 0:35:28 | |

She does say earlier on, "I fear that nobody is going to survive this." | 0:35:28 | 0:35:33 | |

The newspaper serialisation sparked a macabre fascination | 0:35:33 | 0:35:38 | |

with the savagery of the Afghans. | 0:35:38 | 0:35:41 | |

She was a British representative in Kabul. | 0:35:41 | 0:35:44 | |

She was part of the establishment there, part of the machine. | 0:35:44 | 0:35:47 | |

And the fact that she had been attacked by the Afghans, | 0:35:47 | 0:35:51 | |

it meant that the Afghans were particularly dastardly | 0:35:51 | 0:35:54 | |

because they had attacked what was most, not sacred, | 0:35:54 | 0:35:57 | |

but almost sacred, about British society abroad. | 0:35:57 | 0:35:59 | |

But, actually, that's extremely unfair because, in fact, | 0:35:59 | 0:36:02 | |

the Afghans went out of their way to save all the women and children. | 0:36:02 | 0:36:05 | |

Yes, but that's not what the audience got from this. Not at all. | 0:36:05 | 0:36:08 | |

What they saw was the sensation. | 0:36:08 | 0:36:10 | |

What they was the dead bodies. What they saw was the cannibalism. | 0:36:10 | 0:36:13 | |

Perhaps to limit the damage to our imperial reputation, | 0:36:14 | 0:36:18 | |

the British spun this as a story of heroism and bravery. | 0:36:18 | 0:36:22 | |

The way this was treated when it was published was, indeed, propaganda, I think. | 0:36:22 | 0:36:27 | |

She was paraded before Queen Victoria. | 0:36:27 | 0:36:30 | |

There was a city named Sale in Australia. There was a ship named Sale in the Navy. | 0:36:30 | 0:36:34 | |

And she was promoted as a heroine. | 0:36:34 | 0:36:36 | |

She was made into a celebrity to try and distract, I think. | 0:36:36 | 0:36:40 | |

-We're defeated, but we turn out of the defeat the fact that we're really lions. -Yes, yeah. | 0:36:40 | 0:36:45 | |

The British Empire had been humiliated. | 0:36:50 | 0:36:53 | |

And the defeat was seared into our historical memory, | 0:36:53 | 0:36:56 | |

creating a view of Afghanistan as a graveyard of empire, an unconquerable land. | 0:36:56 | 0:37:02 | |

But that's only part of the story, because later that year the British sent an army of retribution, | 0:37:03 | 0:37:09 | |

which sought savage revenge for its losses | 0:37:09 | 0:37:13 | |

and razed to the ground Kabul's historic bazaar. | 0:37:13 | 0:37:16 | |

But, having dealt the Afghans a punishing blow, | 0:37:16 | 0:37:19 | |

instead of occupying the country, they ended the first Anglo-Afghan war with a deal. | 0:37:19 | 0:37:25 | |

At this point they announce, "Now we're going to withdraw. | 0:37:28 | 0:37:31 | |

"But now you can see that if we want to come back, we can do it. | 0:37:31 | 0:37:35 | |

"You guys have not defeated us militarily. | 0:37:35 | 0:37:37 | |

"Now we need to cut a deal." | 0:37:37 | 0:37:39 | |

And they take Dost Mohammad, the ruler that they had dispossessed, | 0:37:39 | 0:37:43 | |

they say, "OK, you can go back again." | 0:37:43 | 0:37:45 | |

So it's like Dost Mohammad part two, | 0:37:45 | 0:37:49 | |

but he tells the British, "I understand your needs. You must understand mine," | 0:37:49 | 0:37:53 | |

and the two sides come to a modus vivendi. | 0:37:53 | 0:37:56 | |

So, yes, the Afghans can claim a great victory but, on the other hand, the ruler they've put back in power | 0:37:56 | 0:38:02 | |

understands what Britain needs to such an extent | 0:38:02 | 0:38:05 | |

that when the mutiny occurs in India in 1857, | 0:38:05 | 0:38:08 | |

the so-called Sepoy rebellion, | 0:38:08 | 0:38:10 | |

and the Afghans are urged to march on Peshawar to ally with the rebels, | 0:38:10 | 0:38:14 | |

Dost Mohammad says, "No, I've signed an agreement with the British and, | 0:38:14 | 0:38:17 | |

"besides, I think they'll win." | 0:38:17 | 0:38:19 | |

The Afghans took enormous pride in their resistance to the British, | 0:38:23 | 0:38:27 | |

and the political settlement led to | 0:38:27 | 0:38:29 | |

a period of confidence and relative stability, | 0:38:29 | 0:38:31 | |

during which time the British and the Afghans treated each other with a wary respect. | 0:38:31 | 0:38:37 | |

But the rivalry between Russia and Britain only continued to intensify. | 0:38:39 | 0:38:43 | |

A thousand miles from Afghanistan, in 1854, | 0:38:47 | 0:38:51 | |

the two powers fought a brutal war in the Crimea. | 0:38:51 | 0:38:55 | |

And, if anything, the fears of Russian ambition was growing. | 0:38:55 | 0:39:00 | |

Then, in the late 1870s, Russians again appeared in Kabul. | 0:39:00 | 0:39:05 | |

A new generation of British hawks decided the only response was again to invade. | 0:39:05 | 0:39:11 | |

Again, there was a public outcry. | 0:39:11 | 0:39:14 | |

Again, imperial paranoia triumphed | 0:39:14 | 0:39:17 | |

and once again a British army, this time 40,000 strong, | 0:39:17 | 0:39:21 | |

was marching into Afghanistan. | 0:39:21 | 0:39:24 | |

To prevent Kabul being taken, | 0:39:24 | 0:39:26 | |

the Afghan emir signed an agreement with the British that a new envoy, | 0:39:26 | 0:39:30 | |

Sir Louis Cavagnari, another swashbuckling multilingual officer, | 0:39:30 | 0:39:35 | |

was installed in Kabul. | 0:39:35 | 0:39:37 | |

Remembering that Burnes had been massacred escaping from his unfortified house in the old city, | 0:39:37 | 0:39:43 | |

Cavagnari took up residency in this ancient citadel, the Bala Hisar. | 0:39:43 | 0:39:48 | |

Sir Louis Cavagnari, the new British envoy, | 0:39:48 | 0:39:51 | |

rode in on his elephant into this citadel with a tiny escort. | 0:39:51 | 0:39:55 | |

He'd taken three lessons from the death of his predecessor Alexander Burnes. | 0:39:55 | 0:40:00 | |

Always live within the fortified citadel. | 0:40:00 | 0:40:03 | |

Don't come in with a large army of occupation, | 0:40:03 | 0:40:06 | |

and never touch the local women. | 0:40:06 | 0:40:08 | |

But despite all his care, he was soon hearing rumours that the Afghans wanted to kill him. | 0:40:08 | 0:40:14 | |

Cavagnari thought he had learned from Burnes that it was | 0:40:14 | 0:40:18 | |

better to be in the Bala Hisar, | 0:40:18 | 0:40:20 | |

but this was actually the palace of the Afghan kings, | 0:40:20 | 0:40:23 | |

and his presence there also caused offence. | 0:40:23 | 0:40:27 | |

Here I met up with Prince Ali Seraj, a member of the Afghan royal family | 0:40:29 | 0:40:34 | |

whose palace this was. | 0:40:34 | 0:40:36 | |

People were not very pleased that a British Ambassador had been put in the Bala Hisar. | 0:40:38 | 0:40:42 | |

Why were the angry about that? | 0:40:42 | 0:40:44 | |

Because it reminded them of the first Anglo-Afghan war, | 0:40:44 | 0:40:46 | |

they forget here comes the British again you know, | 0:40:46 | 0:40:50 | |

and they're here to occupy Afghanistan once again. | 0:40:50 | 0:40:53 | |

We have never, ever liked to be conquered. | 0:40:53 | 0:40:57 | |

We have accepted poverty because we want to be free. | 0:40:57 | 0:41:01 | |

They don't understand the Afghan psyche. | 0:41:01 | 0:41:03 | |

They forget that they were in India and they took the East Indian Company, | 0:41:03 | 0:41:07 | |

you know, were so successful in India, they think, | 0:41:07 | 0:41:09 | |

"Oh, Afghanistan, rowdy people with baggy pants and turbans," you know, | 0:41:09 | 0:41:13 | |

we're easy to rule, easy to control, | 0:41:13 | 0:41:15 | |

but they forgot that Afghanistan is a nation of warriors. | 0:41:15 | 0:41:19 | |

I couldn't help asking him if we were making the same mistakes today. | 0:41:19 | 0:41:24 | |

There was an American, I'll not say which organisation, he say, | 0:41:24 | 0:41:28 | |

"Oh, Prince Ali, I have received a billion dollars from the United States." | 0:41:28 | 0:41:32 | |

I said, "What are you going to do with this money? | 0:41:32 | 0:41:34 | |

He said, "Well, we're going to roll into the village and we're going to build things." | 0:41:34 | 0:41:38 | |

I said, "Sir, if you roll into the village, they'll roll you out." | 0:41:38 | 0:41:42 | |

I said, "You roll up to the village, then you send an emissary inside the village, | 0:41:42 | 0:41:46 | |

"talk to the elders. They will do one of two things. | 0:41:46 | 0:41:49 | |

"Either invite you in or they will send somebody out to meet with you. | 0:41:49 | 0:41:53 | |

"Then once they invite you in, you sit down and you talk to them, | 0:41:53 | 0:41:56 | |

"but don't tell them what you're going to do. | 0:41:56 | 0:41:58 | |

"Ask them what they want. | 0:41:58 | 0:42:00 | |

"Respect. If you do that, you will have them in your pocket." | 0:42:00 | 0:42:03 | |

The Afghan king who'd negotiated with the British was seen as weak. | 0:42:03 | 0:42:08 | |

Ordinary Afghans hated the deal he'd struck with the British | 0:42:08 | 0:42:12 | |

and they hated the presence of Cavagnari in Kabul. | 0:42:12 | 0:42:16 | |

Finally, an Afghan regiment mutinied and marched on his residence. | 0:42:16 | 0:42:20 | |

Cavagnari looked out on the screaming mob, | 0:42:20 | 0:42:23 | |

knowing the nearest reinforcements were hundreds of miles away. | 0:42:23 | 0:42:26 | |

He led a suicidal charge, | 0:42:26 | 0:42:28 | |

was killed, and his mutilated corpse was put on display. | 0:42:28 | 0:42:33 | |

Mortified by his death and desperate to salvage their credibility, | 0:42:34 | 0:42:38 | |

Britain launched another invasion into Afghanistan. | 0:42:38 | 0:42:41 | |

The commander of the lead column, General Roberts, was told | 0:42:41 | 0:42:45 | |

"Your objective should be to strike terror and to strike it swiftly and deeply." | 0:42:45 | 0:42:51 | |

Four weeks after the envoy was killed, | 0:42:51 | 0:42:54 | |

a Highland Regiment had fought its way to the top of that ridgeline | 0:42:54 | 0:42:59 | |

and the next day General Roberts had seized Kabul. | 0:42:59 | 0:43:02 | |

He came here to the citadel where he saw the blood-spattered walls | 0:43:02 | 0:43:06 | |

and the mangled corpse of the envoy and his comrades. | 0:43:06 | 0:43:10 | |

Enraged, General Roberts set up a gallows on the wall. | 0:43:10 | 0:43:14 | |

He hanged a hundred Afghans, | 0:43:14 | 0:43:15 | |

demolished the palaces of the Afghan nobility | 0:43:15 | 0:43:19 | |

and, at that point, with honour satisfied, | 0:43:19 | 0:43:22 | |

many suggested he should withdraw. | 0:43:22 | 0:43:24 | |

But the Afghan king had been deposed, the country was unstable, | 0:43:24 | 0:43:28 | |

Britain had taken responsibility for Afghanistan and leaving no longer seemed an option. | 0:43:28 | 0:43:35 | |

While General Roberts sat in Kabul, | 0:43:37 | 0:43:40 | |

the countryside was now in revolt. | 0:43:40 | 0:43:43 | |

Suddenly, a jihad had been called against them and when | 0:43:43 | 0:43:46 | |

they looked out on a winter evening from their small camp in Kabul, | 0:43:46 | 0:43:51 | |

they could see right along this ridgeline, | 0:43:51 | 0:43:54 | |

60,000 watch fires burning from Afghans bent on their destruction. | 0:43:54 | 0:43:59 | |

It must have seemed as though history was repeating itself exactly, | 0:44:00 | 0:44:05 | |

and the one lesson that Britain should be taking away was never to invade Afghanistan. | 0:44:05 | 0:44:11 | |

This time, unlike his predecessor, | 0:44:11 | 0:44:15 | |

General Roberts decided to stay and fight and he was able, just, | 0:44:15 | 0:44:19 | |

to withstand the siege of his compound in Kabul. | 0:44:19 | 0:44:23 | |

But in Helmand Province, the Afghans completely defeated and wiped out another British unit, | 0:44:23 | 0:44:28 | |

this time in the Battle of Maiwand. | 0:44:28 | 0:44:32 | |

It's one of Afghanistan's most famous victories | 0:44:32 | 0:44:37 | |

and I met Abbie Aryan, an Afghan living in London, | 0:44:37 | 0:44:40 | |

at this British memorial to Maiwand. | 0:44:40 | 0:44:42 | |

History has it that the Afghans won | 0:44:42 | 0:44:44 | |

because of the rousing battle cry of a young woman called Malalai. | 0:44:44 | 0:44:48 | |

She's an ordinary Afghan girl. | 0:44:50 | 0:44:52 | |

As she's standing in the battle, she can see that the Afghans are losing | 0:44:52 | 0:44:56 | |

and she stood there, took her veil off and said, | 0:44:56 | 0:44:59 | |

"If you love your country and if you're a real Pashtun, | 0:44:59 | 0:45:02 | |

"and if you don't want to be ashamed, you have to go and fight the British." | 0:45:02 | 0:45:06 | |

-Remember when Elizabeth stood in front of Spanish Armada... -Uh-huh. | 0:45:06 | 0:45:11 | |

-..gave this speech to the British army? -Yep. | 0:45:11 | 0:45:14 | |

To us, that was equivalent to that. | 0:45:14 | 0:45:16 | |

And by revealing her face, actually, in some ways, | 0:45:16 | 0:45:18 | |

it's a kind of shame for her and her family, everybody sees her face. | 0:45:18 | 0:45:22 | |

But she's going to die so it doesn't matter? | 0:45:22 | 0:45:24 | |

Absolutely. And she, in fact, she dies in the battle as well, | 0:45:24 | 0:45:28 | |

but the encouragement she gave to the Afghans there was immense. | 0:45:28 | 0:45:32 | |

Unlike the massacre of the British army in the retreat from Kabul, | 0:45:32 | 0:45:36 | |

Maiwand was not covered in a serialisation in The Times. | 0:45:36 | 0:45:39 | |

So although a thousand British soldiers were killed, | 0:45:39 | 0:45:43 | |

this memorial in Reading is almost all that remains, | 0:45:43 | 0:45:46 | |

and its meaning is now largely forgotten. | 0:45:46 | 0:45:49 | |

But ask an Afghan and you get a very different response. | 0:45:49 | 0:45:52 | |

This battle, like the retreat from Kabul, is still the stuff of legend. | 0:45:52 | 0:45:58 | |

As an Afghan child, as you learn how to walk, | 0:45:58 | 0:46:01 | |

-you know about the battles we had with the British. -Uh-huh. | 0:46:01 | 0:46:05 | |

It is part of our DNA It's part of our life. | 0:46:05 | 0:46:08 | |

Maiwand is like a legend in Afghanistan. | 0:46:08 | 0:46:11 | |

I think, in a way, the British try to justify it, saying, | 0:46:11 | 0:46:14 | |

"Oh, it was really sunny hot day. We didn't have as much as... | 0:46:14 | 0:46:18 | |

"Afghans had superior fire power." | 0:46:18 | 0:46:20 | |

How can Afghan army have a superior fire power than the British?! | 0:46:20 | 0:46:24 | |

British troops fighting in Helmand today are often warned by local Afghans | 0:46:25 | 0:46:30 | |

that they will meet the same fate as befell their predecessors in Helmand at Maiwand. | 0:46:30 | 0:46:36 | |

We say that all doors are always open for invaders. | 0:46:36 | 0:46:39 | |

Look from Alexander The Great, all the way to the British and today. | 0:46:39 | 0:46:43 | |

It's really easy to get into Afghanistan. | 0:46:43 | 0:46:45 | |

It's just the getting-out part that's very difficult. | 0:46:45 | 0:46:48 | |

We always don't mind foreign invaders getting in there, | 0:46:48 | 0:46:51 | |

relaxing and feeling comfortable, then we start our fight. | 0:46:51 | 0:46:55 | |

This is our traditional way of doing things. | 0:46:55 | 0:46:57 | |

What do you think an Afghan villager feels they're fighting for? | 0:46:57 | 0:47:00 | |

For their home and country. For their independence. | 0:47:00 | 0:47:04 | |

They don't like foreign invading army to come through their villages. | 0:47:04 | 0:47:08 | |

To do it with your mighty force and say, | 0:47:08 | 0:47:11 | |

"Look, I'm here, I'm going to provide you peace and security." | 0:47:11 | 0:47:14 | |

This is a joke, honestly is, because nobody believe that. | 0:47:14 | 0:47:17 | |

Afghans wouldn't accept that - as how can somebody bring peace with a gun and weapons? | 0:47:17 | 0:47:22 | |

You can't do that. | 0:47:22 | 0:47:23 | |

A thousand British soldiers had been massacred at the Battle of Maiwand, | 0:47:26 | 0:47:31 | |

the war was turning against Britain, | 0:47:31 | 0:47:33 | |

but the response this time was immediate. | 0:47:33 | 0:47:36 | |

There followed one of the most celebrated marches of the entire Victorian era, | 0:47:36 | 0:47:42 | |

General Roberts, with an elite band of Ghurkhas and Highlanders, | 0:47:42 | 0:47:45 | |

set off from Kabul, through unknown territory with no support. | 0:47:45 | 0:47:50 | |

320 miles, in 20 days, | 0:47:50 | 0:47:55 | |

in 100-degree heat, arrived safe at Kandahar, | 0:47:55 | 0:47:59 | |

and won a decisive victory that brought the second Anglo-Afghan war to a close. | 0:47:59 | 0:48:06 | |

Having won a victory, the question was, what would Britain do next? | 0:48:10 | 0:48:14 | |

All the fears, all the pride that had dragged them into Afghanistan was still there. | 0:48:14 | 0:48:19 | |

They'd spent blood and treasure. | 0:48:19 | 0:48:21 | |

There were so many reasons to try to continue an occupation | 0:48:21 | 0:48:26 | |

and yet they decided to declare a victory and get out. | 0:48:26 | 0:48:31 | |

And this is because, despite all these fears, | 0:48:31 | 0:48:34 | |

the British Empire had a lot of people who knew the region well, | 0:48:34 | 0:48:38 | |

who spoke the languages well, who understood their limits, | 0:48:38 | 0:48:42 | |

who understood that it couldn't be done. | 0:48:42 | 0:48:45 | |

And nobody summed it up better than General Roberts himself. | 0:48:45 | 0:48:49 | |

He said, "We have nothing to fear from Afghanistan | 0:48:50 | 0:48:54 | |

"and, offensive though it may be to our pride, the less they see of us, | 0:48:54 | 0:48:59 | |

"the less they will dislike us." | 0:48:59 | 0:49:02 | |

After decades of battling Russian influence in Afghanistan, | 0:49:12 | 0:49:15 | |

the British Empire, at the peak of its power, | 0:49:15 | 0:49:19 | |

bowed to Afghan realities and struck a deal with their opponent. | 0:49:19 | 0:49:24 | |

Just as in 1842, Britain again allowed the most powerful | 0:49:24 | 0:49:28 | |

Afghan leader to take the throne, even though he was their enemy. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:33 | |

Abdur Rahman was an ally of the Russians | 0:49:33 | 0:49:36 | |

and had been living on Russian soil, | 0:49:36 | 0:49:38 | |

but he was the only man who seemed to have the support and authority to control the country. | 0:49:38 | 0:49:44 | |

It's as though after ten years of fighting the Taliban today, | 0:49:44 | 0:49:48 | |

the United States and their allies left Afghanistan | 0:49:48 | 0:49:51 | |

and put the Taliban back in charge. | 0:49:51 | 0:49:53 | |

This extraordinary gamble paid off. | 0:49:55 | 0:49:58 | |

For his part, the new king, Abdur Rahman, | 0:49:58 | 0:50:01 | |

demanded a massive subsidy and no internal interference in his country. | 0:50:01 | 0:50:05 | |

In return, Britain got control of Afghan foreign policy | 0:50:05 | 0:50:08 | |

and, most importantly, Abdur Rahman did not allow the Russians to threaten British India. | 0:50:08 | 0:50:14 | |

For Britain, it was a perfect solution. | 0:50:14 | 0:50:17 | |

And even when Europe descended into the First World War, | 0:50:24 | 0:50:27 | |

Afghanistan remained neutral. | 0:50:27 | 0:50:29 | |

But this would change in the aftermath of that Great War, | 0:50:31 | 0:50:34 | |

as the great powers of Europe met here in Versailles. | 0:50:34 | 0:50:38 | |

Here, empires were broken up, new nation states were created, | 0:50:40 | 0:50:44 | |

and Afghanistan, although excluded from the negotiating table, | 0:50:44 | 0:50:48 | |

had its own ambitions. | 0:50:48 | 0:50:50 | |

For the first time, Afghanistan, | 0:50:54 | 0:50:55 | |

so often on the receiving end of British firepower, | 0:50:55 | 0:50:58 | |

itself became the principle aggressor. | 0:50:58 | 0:51:01 | |

The new king of Afghanistan saw Britain exhausted by war, | 0:51:02 | 0:51:06 | |

facing unrest in India. | 0:51:06 | 0:51:09 | |

He called another jihad, took his chance | 0:51:09 | 0:51:11 | |

and invaded British India through the Khyber Pass. | 0:51:11 | 0:51:14 | |

Although Britain saw off this unexpected aggression, | 0:51:17 | 0:51:20 | |

they suffered twice as many casualties as the Afghans. | 0:51:20 | 0:51:23 | |

But with Russia no longer the threat of old, | 0:51:24 | 0:51:27 | |

Britain saw less need for an interest in Afghanistan and granted the Afghans full independence. | 0:51:27 | 0:51:33 | |

But what Afghanistan did with that independence was the opposite | 0:51:36 | 0:51:40 | |

of what the British expected. | 0:51:40 | 0:51:42 | |

The new king, Amanullah, revealed himself to be a moderniser. | 0:51:45 | 0:51:50 | |

The British policy was really to keep Afghanistan locked in the Middle Ages. | 0:51:50 | 0:51:56 | |

The last thing they wanted was Afghanistan to change | 0:51:56 | 0:51:59 | |

and modernise and then, suddenly, in 1919, modernity came. | 0:51:59 | 0:52:05 | |

British ideas came to Afghanistan against Britain's will, | 0:52:05 | 0:52:09 | |

and this great process of modernisation came not through the empire, | 0:52:09 | 0:52:15 | |

came not through British bayonets, but through an Afghan king. | 0:52:15 | 0:52:20 | |

King Amanullah ruled from this extravagant palace in a European style, | 0:52:20 | 0:52:25 | |

which he built on the outskirts of Kabul, | 0:52:25 | 0:52:28 | |

and he championed a new modernising intellectual elite in Afghanistan. | 0:52:28 | 0:52:33 | |

But the country that he was determined to transform | 0:52:33 | 0:52:36 | |

had changed little in the century that had passed | 0:52:36 | 0:52:39 | |

since Britain first took an interest here. | 0:52:39 | 0:52:41 | |

It was a country with almost blanket illiteracy, | 0:52:41 | 0:52:44 | |

a fragmented country of isolated villages | 0:52:44 | 0:52:47 | |

and mountain valleys under feudal rule, | 0:52:47 | 0:52:50 | |

the way Britain had found it and left it. | 0:52:50 | 0:52:53 | |

Dreaming of modernity, in 1927, | 0:52:58 | 0:53:00 | |

Amanullah embarks on a grand European tour, | 0:53:00 | 0:53:03 | |

the first such trip by an Afghan ruler. | 0:53:03 | 0:53:06 | |

The Afghan king arrived in Britain for a full state visit. | 0:53:11 | 0:53:15 | |

The flags were out and a slightly anxious British government | 0:53:15 | 0:53:18 | |

responded in time-honoured fashion by taking him to shop for guns and for cars, | 0:53:18 | 0:53:25 | |

which his impoverished country could hardly afford. | 0:53:25 | 0:53:29 | |

And when he toured the Rolls Royce factory, | 0:53:35 | 0:53:38 | |

he bought a fleet of cars to take back home. | 0:53:38 | 0:53:42 | |

It started a long love affair between Afghan royalty and Rolls Royce. | 0:53:42 | 0:53:46 | |

And this car was later part of their fleet, | 0:53:46 | 0:53:49 | |

now owned by businessman Richard Raynsford. | 0:53:49 | 0:53:53 | |

For an Afghan, possessing this car shows that you are part of an international group. | 0:53:53 | 0:53:57 | |

You're no longer part of an isolated country at the other end of the world. | 0:53:57 | 0:54:00 | |

Well, that's right. He was a very sophisticated man. | 0:54:00 | 0:54:03 | |

When he went to Europe in 1928, | 0:54:03 | 0:54:05 | |

he was not just looking for Rolls Royce cars, | 0:54:05 | 0:54:08 | |

he was looking, really, to...means to be inspired by the west | 0:54:08 | 0:54:12 | |

to how he could modernise his very backward country. | 0:54:12 | 0:54:15 | |

And, therefore, the Rolls Royce trip to the Derby works | 0:54:15 | 0:54:18 | |

was part of that overall quest for inspiration and for modernisation. | 0:54:18 | 0:54:23 | |

A car like this at the time was a pretty expensive thing. | 0:54:28 | 0:54:32 | |

It would cost as much as a house in Fulham. | 0:54:32 | 0:54:35 | |

About £1,500 for the chassis | 0:54:35 | 0:54:36 | |

and another £1,500 pounds, even more, up to 2,000, for the body, | 0:54:36 | 0:54:40 | |

depending on how exotic a body was ordered by the excited owner. | 0:54:40 | 0:54:44 | |

What would an Afghan have felt, looking at this kind of car? | 0:54:49 | 0:54:52 | |

It'd be like looking at something equivalent to the space shuttle, | 0:54:52 | 0:54:55 | |

I imagine, to an Afghanistan farmer or peasant. | 0:54:55 | 0:54:57 | |

'I think it's tempting today when we look at a car like this | 0:55:01 | 0:55:04 | |

'to imagine Amanullah as some sort of corrupt dictator | 0:55:04 | 0:55:08 | |

'who was spraying money around on Rolls Royces,' | 0:55:08 | 0:55:12 | |

but in fact, really, this is part of his love of technology or machinery. | 0:55:12 | 0:55:16 | |

It's as though he's returning to the country with a jet engine or a new computer system. | 0:55:16 | 0:55:21 | |

He's coming back with whole new interests in railways and printing machines, | 0:55:21 | 0:55:26 | |

and mining technology and medicine, | 0:55:26 | 0:55:28 | |

but for the conservatives in Afghanistan, this is all very dangerous and very dubious. | 0:55:28 | 0:55:34 | |

The big story that's spreading through the streets when he arrives | 0:55:34 | 0:55:38 | |

is he's bringing back a new machine to turn human corpses into soap. | 0:55:38 | 0:55:42 | |

Amanullah was just beginning to discover how conservative his country still was. | 0:55:42 | 0:55:47 | |

Wild rumours were circulating about how he had become a Catholic, | 0:55:47 | 0:55:51 | |

ate pork, drank alcohol. | 0:55:51 | 0:55:54 | |

He became perceived as a foreigner in his own land, | 0:55:54 | 0:55:57 | |

attempting to impose a foreign ideology on his own people. | 0:55:57 | 0:56:01 | |

It's easy to laugh at Amanullah and, indeed, there's a lot that you can laugh at him for. | 0:56:03 | 0:56:07 | |

For example, he gathered the tribal elders | 0:56:07 | 0:56:09 | |

and insisted they wore pinstriped trousers and western jackets, | 0:56:09 | 0:56:13 | |

but there was also a highly developed serious programme of reform. | 0:56:13 | 0:56:17 | |

In fact, the most radical programme for state transformation | 0:56:17 | 0:56:20 | |

in Afghanistan came from an Afghan. | 0:56:20 | 0:56:23 | |

He wanted parliamentary elections, a progressive constitution, | 0:56:23 | 0:56:26 | |

education, particularly for women. | 0:56:26 | 0:56:29 | |

And, in the end, when photographs were circulated in the bazaar | 0:56:29 | 0:56:33 | |

of his wife, the queen, with her head uncovered, | 0:56:33 | 0:56:36 | |

with pearls over a plunging neckline, he had to flee, | 0:56:36 | 0:56:40 | |

the wheels of that new Rolls Royce spinning vainly in the snow, to exile in Italy. | 0:56:40 | 0:56:48 | |

It is ironic, when, today, we're concerned with the powerful hold of Islam | 0:56:52 | 0:56:56 | |

and the problems of establishing democracy in that country, | 0:56:56 | 0:56:59 | |

that the only attempt in this whole period to modernise and democratise Afghanistan | 0:56:59 | 0:57:05 | |

didn't come from British rule, but from the Afghans themselves. | 0:57:05 | 0:57:09 | |

So why did the British go into Afghanistan in the 19th century? | 0:57:13 | 0:57:17 | |

It wasn't really about Afghanistan in the end. | 0:57:17 | 0:57:20 | |

It was about the fears of empire, fear of empty space, | 0:57:20 | 0:57:23 | |

fear of the Russians, fear in the end about their own credibility, their pride. | 0:57:23 | 0:57:28 | |

In the second film, two superpowers come calling, | 0:57:31 | 0:57:34 | |

and these armies invade Afghanistan, | 0:57:34 | 0:57:36 | |

not just to protect their selfish strategic aims, | 0:57:36 | 0:57:40 | |

but also with the objective of bringing profound social change, | 0:57:40 | 0:57:44 | |

and reshaping Afghanistan more in their own image. | 0:57:44 | 0:57:48 | |

And the result for the people of Afghanistan, | 0:57:48 | 0:57:51 | |

and their invaders, was to be even greater horror and tragedy. | 0:57:51 | 0:57:56 | |

If you were going to pass a message to the American | 0:57:56 | 0:58:00 | |

and British troops today, what would you say to them? | 0:58:00 | 0:58:03 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:58:37 | 0:58:40 |