Chaos and Consent Nazis: A Warning from History

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Chaos and Consent. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

The Nazis were obsessed with images of order. | 0:01:12 | 0:01:16 | |

In their museums, exhibits like this "glass man" | 0:01:16 | 0:01:20 | |

showed how the perfect human body was ordered into one interlocking whole. | 0:01:20 | 0:01:26 | |

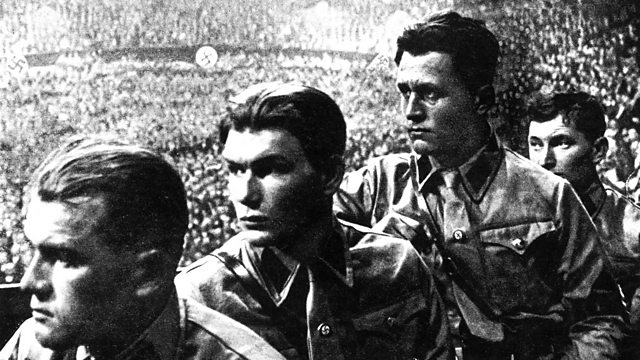

And through their parades and pageants, they sought to show how one individual human being | 0:01:29 | 0:01:36 | |

was but a part of the ordered national community. | 0:01:36 | 0:01:40 | |

But in Germany, the Nazis only created an illusion of order. | 0:01:44 | 0:01:49 | |

On January 30th, 1933, | 0:02:26 | 0:02:29 | |

Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. | 0:02:29 | 0:02:33 | |

Chief among those who rejoiced at the news | 0:02:38 | 0:02:42 | |

were the Nazi storm troopers, the party's paramilitary wing, led by Ernst Rohm. | 0:02:42 | 0:02:48 | |

ALL SING ROUSING ANTHEM | 0:03:07 | 0:03:10 | |

In '33, you thought it was the beginning of a new German | 0:03:21 | 0:03:26 | |

wonderful period. | 0:03:26 | 0:03:29 | |

It was a true, enthusiastic movement of the people, | 0:03:29 | 0:03:33 | |

except the people who were, by their hearts, socialists | 0:03:33 | 0:03:38 | |

who were, from the beginning, | 0:03:38 | 0:03:41 | |

persecuted and had to emigrate or were in concentration camps. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:46 | |

One knew of these camps. One said, "The communists would have done the same and this is a revolution." | 0:03:46 | 0:03:53 | |

The first to be imprisoned in this revolution were the Nazis' political opponents, | 0:03:53 | 0:04:00 | |

communists and socialists. They were rounded up and thrown into hastily-built concentration camps. | 0:04:00 | 0:04:07 | |

Hermann Goering boasted that scores were being settled. | 0:04:07 | 0:04:13 | |

All in an atmosphere of chaotic terror, | 0:04:13 | 0:04:16 | |

-as one Nazi storm trooper admitted. -"Everyone is arresting everyone else, avoiding official channels, | 0:04:16 | 0:04:23 | |

"threatening everyone else with protective custody, with Dachau. Every little streetcleaner | 0:04:23 | 0:04:30 | |

"feels he is responsible for matters which he has never understood." | 0:04:30 | 0:04:36 | |

Amongst the first to suffer was Josef Felder. | 0:04:36 | 0:04:39 | |

a Social Democrat MP. | 0:04:39 | 0:04:42 | |

He was sent to the newly-opened Nazi concentration camp outside Munich - Dachau. | 0:04:42 | 0:04:49 | |

Josef Felder was released after 18 months. | 0:05:43 | 0:05:47 | |

The majority of those imprisoned here in 1933 were released after less than a year. | 0:05:47 | 0:05:54 | |

The regime here was brutal. | 0:05:54 | 0:05:57 | |

Beatings and psychological torture were common. But extermination camps were not yet born. | 0:05:57 | 0:06:04 | |

Concentration camps were a tool of oppression, not yet of systematic murder. | 0:06:04 | 0:06:10 | |

In 1933, to many Germans, | 0:06:10 | 0:06:13 | |

they were an acceptable part of the Nazi revolution. | 0:06:13 | 0:06:18 | |

To be a French nobleman in the Bastille was not so agreeable either. | 0:06:18 | 0:06:24 | |

So people said, "Well, this is revolution." | 0:06:24 | 0:06:28 | |

A peaceful revolution, but, partly, it IS a revolution. | 0:06:28 | 0:06:33 | |

And concentration camps... Everybody said, "The English invented them in South Africa with the Boers." | 0:06:33 | 0:06:41 | |

So, you know, eh... | 0:06:41 | 0:06:43 | |

People couldn't look ahead. | 0:06:43 | 0:06:46 | |

It was impossible for somebody in '33 to look ahead to '45. | 0:06:46 | 0:06:52 | |

You can't. | 0:06:52 | 0:06:54 | |

It was only 12 years, but it seems to be too much to look ahead... for 12 years. | 0:06:56 | 0:07:02 | |

But Germans only had to look fewer than 12 weeks into Hitler's chancellorship | 0:07:04 | 0:07:10 | |

to see what the status of the Jews would be in the new Nazi state. | 0:07:10 | 0:07:15 | |

On April 1st, 1933, | 0:07:16 | 0:07:19 | |

the Party organised a boycott of all Jewish shops which lasted one day. | 0:07:19 | 0:07:26 | |

The Nazis made the Jews scapegoats for the loss of World War One and much else besides. | 0:07:26 | 0:07:34 | |

In those early months of the Nazi reign, | 0:07:38 | 0:07:43 | |

German Jews also fell victim to the storm troopers' arbitrary and violent attacks. | 0:07:43 | 0:07:50 | |

In 1933, the storm troopers came | 0:07:50 | 0:07:54 | |

and took my father away, | 0:07:54 | 0:07:58 | |

together with many other Jews in Nuremberg. They were taken to a sports stadium | 0:07:58 | 0:08:04 | |

where there was a lot of grass | 0:08:04 | 0:08:06 | |

and they were made to cut the grass with their teeth, by sort of eating the grass. | 0:08:06 | 0:08:12 | |

I found out afterwards. My father never talked about it. | 0:08:12 | 0:08:18 | |

It was to humiliate them, | 0:08:18 | 0:08:20 | |

to show them that they were the lowest of the low. | 0:08:20 | 0:08:25 | |

It was simply to make a gesture. | 0:08:25 | 0:08:28 | |

Nazi storm troopers made other violent gestures. In 1933, | 0:08:30 | 0:08:35 | |

together with sympathetic students, they organised the burning of unsuitable books, | 0:08:35 | 0:08:41 | |

particularly those by Jewish authors. | 0:08:41 | 0:08:45 | |

Rohm wanted his storm troopers integrated into the regular German army. The army was horrified. | 0:08:49 | 0:08:57 | |

Hitler sympathised with the revolutionary zeal of Rohm and his storm troopers. | 0:09:39 | 0:09:45 | |

But by the summer of 1934, he knew that their power had to be curbed, | 0:09:45 | 0:09:52 | |

and not just to please the army. | 0:09:52 | 0:09:55 | |

Rohm had made a more dangerous enemy than the army leadership. | 0:09:55 | 0:10:00 | |

Heinrich Himmler, ambitious for power himself, and still technically working to Rohm, | 0:10:00 | 0:10:08 | |

plotted his downfall. He concocted a story | 0:10:08 | 0:10:12 | |

that Rohm was plotting a coup and Hitler believed him. | 0:10:12 | 0:10:17 | |

On June 30th, 1934, | 0:10:17 | 0:10:20 | |

while on holiday in Bavaria, he was arrested. | 0:10:20 | 0:10:24 | |

Two days later, he was shot. | 0:10:24 | 0:10:27 | |

The army was glad to see the power of the storm troopers moderated. | 0:10:27 | 0:10:32 | |

To show their gratitude, they volunteered to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler, | 0:10:32 | 0:10:40 | |

who now, on President Hindenburg's death, was not just Chancellor, but head of state. | 0:10:40 | 0:10:46 | |

Somebody was reading and we had to lift our arm, and, at the very end, say, "That's my oath." | 0:11:08 | 0:11:16 | |

How seriously did you and your colleagues take this oath? | 0:11:16 | 0:11:21 | |

VERY seriously. | 0:11:21 | 0:11:24 | |

This accompanied me my whole life till the very end. | 0:11:24 | 0:11:30 | |

I mean, oath is oath. | 0:11:30 | 0:11:33 | |

There's no doubt that I can't break the oath, | 0:11:33 | 0:11:37 | |

otherwise I'm meant to commit suicide if I plan something else. | 0:11:37 | 0:11:42 | |

This is very serious, the oath, for a soldier. | 0:11:42 | 0:11:48 | |

With Rohm dead, Hitler appeared to have restored order. | 0:11:52 | 0:11:57 | |

The revolution on the streets had subsided, and, with his hold on power secure, | 0:11:57 | 0:12:03 | |

Hitler would come here to relax... in the mountains above Berchetesgaden in southern Bavaria. | 0:12:03 | 0:12:10 | |

In 1938, a tea house was built on top of the high Obersalzburg, | 0:12:10 | 0:12:15 | |

so that Hitler and his guests could enjoy the view. | 0:12:15 | 0:12:20 | |

Hitler's own house was lower down the slope, and a whole complex grew up around it. | 0:12:20 | 0:12:26 | |

This was the official guest house. | 0:12:26 | 0:12:29 | |

But all that remains of Hitler's own house is rubble, | 0:12:35 | 0:12:39 | |

the building demolished to prevent it becoming a memorial | 0:12:39 | 0:12:44 | |

and quick-growing trees planted to obscure the famous view. | 0:12:44 | 0:12:49 | |

When Hitler stayed here, as well as when he was in Berlin, | 0:12:51 | 0:12:56 | |

the whole Nazi regime revolved around him. | 0:12:56 | 0:13:00 | |

His personality determined the way in which Germany was governed. | 0:13:01 | 0:13:06 | |

His was not the daily regime of a workaholic. | 0:13:06 | 0:13:11 | |

Hitler was indolent - as those who worked for him discovered. | 0:13:11 | 0:13:17 | |

He normally appeared shortly before lunch, | 0:13:17 | 0:13:20 | |

quickly read the newspaper cuttings, then had lunch. | 0:13:20 | 0:13:24 | |

When Hitler stayed at the Obersalzburg, it was worse. | 0:13:24 | 0:13:28 | |

There, he never left his room before 2pm, then went to lunch. | 0:13:28 | 0:13:33 | |

He spent most afternoons taking a walk. After dinner, there were films. | 0:13:33 | 0:13:40 | |

In the 12 years of his rule in Germany, Hitler produced | 0:13:40 | 0:13:46 | |

the biggest confusion in government that has ever existed in a civilised state. | 0:13:46 | 0:13:53 | |

I've secured important decisions from him without his ever asking to see the relevant files. | 0:13:54 | 0:14:02 | |

He took the view that many things sorted themselves out on their own, if one did not interfere. | 0:14:02 | 0:14:09 | |

A very different picture of Hitler was projected here, at the vast complex of stadiums | 0:14:15 | 0:14:22 | |

built in Nuremberg for the party's annual rally. | 0:14:22 | 0:14:27 | |

What the public saw of Hitler in Nuremberg in the 1930s, | 0:14:29 | 0:14:34 | |

was a confident and strong leader whose oratory promised a new, dynamic and powerful Germany. | 0:14:34 | 0:14:42 | |

He was meant to be seen as the all-powerful, | 0:15:32 | 0:15:36 | |

all-knowing leader, who prevailed over a system of total order. | 0:15:36 | 0:15:42 | |

But the contrast between image and reality was quite a stark one | 0:15:42 | 0:15:48 | |

because, far from it being a very orderly structure of command, | 0:15:48 | 0:15:54 | |

in fact it was very disorganised. | 0:15:54 | 0:15:58 | |

It is a quite remarkable system, if you can call it a system, | 0:15:58 | 0:16:03 | |

where there is no collective government, | 0:16:03 | 0:16:06 | |

yet where the head of state doesn't spend all his time dictating. | 0:16:06 | 0:16:11 | |

SUNG IN GERMAN: "Happy Days Are Here Again" | 0:16:11 | 0:16:15 | |

Hitler and the Nazis created a unique and peculiar form of government. | 0:16:26 | 0:16:32 | |

Hitler was surrounded by acolytes who knew that their future depended on finding a way to please him. | 0:16:32 | 0:16:39 | |

They strove always to be near him, accompanying him on whatever trips took his fancy. | 0:16:39 | 0:16:46 | |

Though Hitler may have had little interest in regular hours of work or policy details, | 0:16:56 | 0:17:02 | |

he did have visions of what he wanted for Germany. | 0:17:02 | 0:17:06 | |

As Hitler talked in an endless monologue, ambitious Nazis would listen to him closely. | 0:17:06 | 0:17:14 | |

Then, on their own initiative, they tried to think of ways in which his vision could become a reality. | 0:17:15 | 0:17:23 | |

They made up the detail policy themselves and said they were acting on the will of the Fuhrer. | 0:17:23 | 0:17:30 | |

From the first, Hitler openly said he didn't have detailed policies. | 0:17:59 | 0:18:04 | |

But Hitler WAS open in saying what he wanted FROM the German economy. | 0:18:52 | 0:18:58 | |

Chiefly, the weapons to build a new German army. Rearmament became his economic priority. | 0:18:58 | 0:19:04 | |

The Nazis increased the army's budget so much in their first year of power, | 0:19:08 | 0:19:14 | |

that the army wasn't able to spend all of it. | 0:19:14 | 0:19:19 | |

The Nazis also promised to rid Germany of unemployment. | 0:19:21 | 0:19:26 | |

And they did - mainly through huge work creation schemes like the Autobahn Building Programme. | 0:19:26 | 0:19:34 | |

But building armaments and Autobahns | 0:19:40 | 0:19:45 | |

could only be a short-term solution to Germany's economic problems. | 0:19:45 | 0:19:50 | |

It would take time for these inflationary pressures to be felt. | 0:20:22 | 0:20:27 | |

For the moment, everything looked rosy, especially when, in 1936, | 0:20:27 | 0:20:33 | |

Hitler ordered German troops to re-enter the demilitarised portion of Germany, the Rhineland. | 0:20:33 | 0:20:40 | |

Germans saw all this as one more sign that their country was regaining its self-respect. | 0:20:40 | 0:20:47 | |

The Nazis organised pageants like Die Nacht der Amazonen - The Night Of The Amazons - | 0:21:39 | 0:21:46 | |

held in Munich in the 1930s - | 0:21:46 | 0:21:49 | |

Celebrations in which only those the Nazis considered racially pure could participate. | 0:21:49 | 0:21:56 | |

But if you didn't fit the Nazi image of the perfect German, then life was very different. | 0:23:50 | 0:23:57 | |

Here, in Munich, the same city where The Night Of The Amazons was held, | 0:23:57 | 0:24:04 | |

the Nazis demolished one of the biggest synagogues in Germany. They wanted the space for a car park. | 0:24:04 | 0:24:12 | |

The Jews were systematically excluded from German life. The 1935 Nuremberg Laws outlawed marriage | 0:24:12 | 0:24:20 | |

between Jews and other Germans and declared that Jews were not German citizens. | 0:24:20 | 0:24:26 | |

Other discrimination followed. | 0:24:26 | 0:24:29 | |

Wasn't it a problem for you that you were working in a system | 0:24:29 | 0:24:34 | |

that allowed Jews to be pushed out of their position, | 0:24:34 | 0:24:39 | |

to lose their wealth, their property? | 0:24:39 | 0:24:43 | |

Surely this was a great injustice. | 0:24:43 | 0:24:46 | |

How did you feel about that? | 0:24:46 | 0:24:49 | |

Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda hugely exaggerated the number of Jews who were in professions. | 0:25:26 | 0:25:33 | |

The Nazis never gave the reason why German Jews were concentrated in certain walks of life - | 0:25:33 | 0:25:42 | |

that the Jews had been banned from other careers for hundreds of years. | 0:25:42 | 0:25:48 | |

Thousands emigrated from Germany during the '30s. They realised they would not be safe during Nazi rule. | 0:25:49 | 0:25:58 | |

Those who remained always risked the attentions of the Secret State Police - | 0:25:58 | 0:26:04 | |

the infamous Gestapo. | 0:26:04 | 0:26:07 | |

In the town of Wurzburg lies a clue to just how the Gestapo operated under the Nazis. | 0:26:08 | 0:26:15 | |

Almost all Gestapo files were burnt by the Nazis as the Allies came into Germany, | 0:26:15 | 0:26:21 | |

but in Wurzburg, American soldiers prevented their destruction. | 0:26:21 | 0:26:26 | |

Only recently have the files been studied, | 0:26:26 | 0:26:29 | |

and a surprising picture emerges of how the Gestapo functioned. | 0:26:29 | 0:26:34 | |

There were only 28 SS officials | 0:26:34 | 0:26:37 | |

for the entire Wurzburg region | 0:26:37 | 0:26:40 | |

of nearly a million people. | 0:26:40 | 0:26:43 | |

I think the Gestapo could not have operated | 0:26:43 | 0:26:48 | |

without the co-operation | 0:26:48 | 0:26:50 | |

of the citizens of Germany. | 0:26:50 | 0:26:53 | |

By that I mean it would have been structurally impossible for them to do so. | 0:26:53 | 0:26:59 | |

There were not enough Gestapo officials to go around. | 0:26:59 | 0:27:04 | |

Between 80-90% of the crimes that were reported to the Gestapo came from ordinary citizens. | 0:27:04 | 0:27:12 | |

The main job for the Gestapo | 0:27:12 | 0:27:15 | |

was sorting out the denunciations. | 0:27:15 | 0:27:18 | |

This seems to have been their preoccupation. | 0:27:19 | 0:27:23 | |

The citizens of a town like Wurzburg didn't so much have to fear the Gestapo, | 0:27:23 | 0:27:30 | |

as what their neighbours might TELL the Gestapo. Every German was at risk from denunciation. | 0:27:30 | 0:27:37 | |

A woman who lived in this house on the outskirts of Wurzburg in 1938 | 0:27:37 | 0:27:42 | |

came to the Gestapo's notice when she was denounced by a relative. | 0:27:42 | 0:27:48 | |

She was called Ilse Sonia Totzke, and her Gestapo file lies in the Wurzburg archive. | 0:27:48 | 0:27:55 | |

After years of Gestapo harassment, she was sent to Ravensbruk Concentration Camp, where she died. | 0:27:55 | 0:28:01 | |

Her crime was simple - she didn't fit in. | 0:28:01 | 0:28:05 | |

She avoided her neighbours and had Jewish friends. | 0:28:05 | 0:28:10 | |

She is put under very general surveillance, not by the Gestapo, | 0:28:12 | 0:28:17 | |

but by the Gestapo asking her neighbours to keep an eye on her. | 0:28:17 | 0:28:22 | |

What happens is that one neighbour after another, for one reason or another, | 0:28:24 | 0:28:30 | |

comes forward with information, all adding up to one thing. | 0:28:30 | 0:28:35 | |

She may be just too unconventional for her own good. | 0:28:35 | 0:28:39 | |

What this does is that - small town mentality - people keep after her... | 0:28:39 | 0:28:46 | |

they keep noticing her... | 0:28:46 | 0:28:49 | |

and it's fuelled again and again by yet another denunciation. | 0:28:49 | 0:28:54 | |

The denunciations in her file contain mostly gossip about her. | 0:28:54 | 0:28:59 | |

That she is acting suspiciously and has shady friends, but little amounts to evidence against her. | 0:28:59 | 0:29:06 | |

One denunciation hints that she may be a lesbian. | 0:29:06 | 0:29:11 | |

"Miss Totzke does not seem to have normal predispositions." Typed in red, | 0:29:11 | 0:29:17 | |

it is signed only "Heil Hitler." | 0:29:17 | 0:29:20 | |

One denunciation is signed by a 20-year-old neighbour, Resi Kraus. | 0:29:27 | 0:29:32 | |

"Since March, 1938, | 0:29:32 | 0:29:35 | |

"Ilse Sonia Totzke is a resident next door to us. | 0:29:35 | 0:29:40 | |

"She rarely has visitors. | 0:29:40 | 0:29:43 | |

"Now and then, a woman of about 36 years old comes, and she is of Jewish appearance... | 0:29:43 | 0:29:50 | |

"I would like to mention that Miss Totzke never responds to the German greeting, Heil Hitler. | 0:29:50 | 0:29:58 | |

"To my mind, Miss Totzke is behaving suspiciously." | 0:29:58 | 0:30:02 | |

We used to think that the population was manipulated and brainwashed from above. | 0:32:17 | 0:32:24 | |

Now what we're beginning to see, | 0:32:24 | 0:32:27 | |

by looking at the social history of the kind one sees in these Gestapo dossiers, | 0:32:27 | 0:32:33 | |

is that the system is manipulated from below by lots of people for all kinds of reasons, | 0:32:33 | 0:32:40 | |

some of them selfish, some of them - fewer - idealistic. | 0:32:40 | 0:32:45 | |

We now get a dramatically different picture of what the system was like. | 0:32:45 | 0:32:51 | |

Ordinary Germans could influence the Gestapo through denunciations. | 0:32:59 | 0:33:04 | |

But no major policy | 0:33:04 | 0:33:06 | |

could ever be successfully instituted unless Hitler blessed it. | 0:33:06 | 0:33:12 | |

So for members of the Nazi elite, the search was always on for a new way of pleasing their Fuhrer. | 0:33:12 | 0:33:19 | |

One way was to feed his anti-Semitism. | 0:33:19 | 0:33:22 | |

Joseph Goebbels, propaganda minister and hater of Jews, | 0:33:22 | 0:33:27 | |

sought to do just that. He boasted that the Nazis had managed to exclude Jews from cultural life. | 0:33:27 | 0:33:36 | |

In the autumn of 1938, Goebbels saw a chance to please Hitler more when he heard | 0:34:05 | 0:34:11 | |

that German diplomat Ernst von Rath, had been assassinated in Paris | 0:34:11 | 0:34:17 | |

by a young Jew, Hirschel Grynszpan, angry at his family's treatment. | 0:34:17 | 0:34:22 | |

The Nazi elite were in Munich for the anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch. | 0:34:22 | 0:34:28 | |

Goebbels asked Hitler's permission to let loose the storm troopers | 0:34:28 | 0:34:33 | |

in an act of vengeance against Germany's innocent Jews. He agreed. And so began Kristallnacht - | 0:34:33 | 0:34:40 | |

the night of broken glass. | 0:34:40 | 0:34:43 | |

In the early hours of the morning, | 0:34:57 | 0:34:59 | |

they broke the front door down and started to smash the place up. | 0:34:59 | 0:35:04 | |

Hoards of storm troopers. | 0:35:04 | 0:35:07 | |

We had two lots. | 0:35:07 | 0:35:10 | |

One lot smashed things up and left, and then the second lot arrived. | 0:35:10 | 0:35:16 | |

Three elderly ladies were living on the first floor. One was dragged out and beaten... | 0:35:18 | 0:35:25 | |

for no reason except she probably got in the way of someone. | 0:35:25 | 0:35:30 | |

I was knocked about... | 0:35:30 | 0:35:32 | |

and finally ended up in the cellar... | 0:35:32 | 0:35:36 | |

which was where the kitchens were. | 0:35:36 | 0:35:39 | |

I was being knocked about. When I came back, I went upstairs, | 0:35:39 | 0:35:45 | |

and found my father dying. | 0:35:45 | 0:35:48 | |

Dead. | 0:35:48 | 0:35:50 | |

I tried... | 0:35:50 | 0:35:53 | |

as far as I could... artificial respiration. | 0:35:53 | 0:35:57 | |

I don't think I was very good at it. In any case, | 0:35:57 | 0:36:01 | |

it was too late for me. | 0:36:01 | 0:36:04 | |

I was absolutely in shock. It was beyond my comprehension. | 0:36:04 | 0:36:10 | |

I didn't know the people, they didn't know me. They had no grudge against me. They were just... | 0:36:10 | 0:36:18 | |

people who would come to do whatever they thought they should do. | 0:36:18 | 0:36:23 | |

More than 800 Jews are known to have lost their lives as a result of Kristallnacht, | 0:36:23 | 0:36:29 | |

and as many as 1,000 synagogues were destroyed. | 0:36:29 | 0:36:33 | |

What was the reaction of the non-Jews you knew, when they heard of your circumstances? | 0:37:52 | 0:38:00 | |

-Did anyone come up to you to say what they felt about it? -No. | 0:38:00 | 0:38:05 | |

In fact... | 0:38:05 | 0:38:08 | |

..the people passing the next morning, ordinary Germans, threw stones at the windows. | 0:38:09 | 0:38:16 | |

-Nobody expressed any sympathy? -No. | 0:38:19 | 0:38:22 | |

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, Hitler's popularity did not seem to suffer. | 0:38:27 | 0:38:34 | |

As he never spoke about it in public, it was possible to believe, | 0:38:34 | 0:38:39 | |

for those Germans who wanted to, that the responsibility lay with the hot-headed storm troopers. | 0:38:39 | 0:38:47 | |

The love affair between Hitler and his followers continued. | 0:38:49 | 0:38:55 | |

MALE SINGER: | 0:39:09 | 0:39:12 | |

In 1938, a new chancellory was built, symbolising the power and order of Nazi rule. | 0:39:42 | 0:39:49 | |

But inside its walls, | 0:39:49 | 0:39:52 | |

Hitler was still pursuing methods which could only result in administrative chaos. | 0:39:52 | 0:39:59 | |

The Grand Reich Chancellory was a hive of political in-fighting. | 0:39:59 | 0:40:04 | |

Rivals with ill-defined jobs fought each other for Hitler's favour. | 0:40:04 | 0:40:09 | |

Hitler's working life was organised by FIVE private offices. | 0:40:09 | 0:40:14 | |

The office of the Reich Chancellory, under Hans Heinrich Lammers. | 0:40:14 | 0:40:19 | |

The office of Hitler's Personal Adjutant, under Wilhelm Bruckner. | 0:40:19 | 0:40:24 | |

The office of the Presidential Chancellory under Otto Meissner. | 0:40:24 | 0:40:29 | |

On the second floor, the office of the Chancellory of the Fuhrer, under Philip Buhler. | 0:40:29 | 0:40:35 | |

And the office representing the Fuhrer's Deputy, under Martin Bormann. | 0:40:35 | 0:40:41 | |

All of these different offices claimed to represent Hitler. | 0:40:41 | 0:40:46 | |

A large portion of their time was spent fighting each other. | 0:40:46 | 0:40:52 | |

One of the more vicious power battles was over access to the mail, | 0:41:49 | 0:41:55 | |

to the thousands of letters that arrived each week addressed only to "Mein Fuhrer" | 0:41:55 | 0:42:02 | |

and which begged favours or blessings from Hitler. | 0:42:02 | 0:42:07 | |

There were trivial letters asking if church bells could be named after Hitler | 0:42:07 | 0:42:14 | |

and serious ones from individual Jews, pleading that they were special cases | 0:42:14 | 0:42:20 | |

and should be exempt from the discriminatory laws. | 0:42:20 | 0:42:24 | |

Access to this mail meant access to Hitler and a chance to form Nazi policy. | 0:42:24 | 0:42:30 | |

Philip Buhler, an ambitious Nazi, | 0:42:30 | 0:42:33 | |

managed to gain control of the mail and exploit it to his benefit. | 0:42:33 | 0:42:38 | |

In late 1938 or early 1939, | 0:42:38 | 0:42:40 | |

one chance letter which Buhler's office showed to Hitler, had a devastating effect. | 0:42:40 | 0:42:48 | |

It was from the father of a mentally disabled child | 0:42:48 | 0:42:52 | |

who asked the Fuhrer's permission to have the child killed. Hitler agreed. | 0:42:52 | 0:42:59 | |

He had already ordered the sterilisation of the disabled. | 0:42:59 | 0:43:04 | |

This one letter was to be the catalyst to their murder. | 0:43:04 | 0:43:09 | |

Buhler was to devise secret policy for killing disabled children | 0:43:09 | 0:43:14 | |

within days of their birth. | 0:43:14 | 0:43:17 | |

This form had to be filled in when a disabled baby was born. | 0:43:17 | 0:43:22 | |

Three doctors read the form. | 0:43:22 | 0:43:25 | |

If they thought the baby should be killed, they each marked it with a cross. | 0:43:25 | 0:43:31 | |

Within months, it was no longer just babies who could be killed, but disabled children, too. | 0:43:31 | 0:43:38 | |

Gerda Bernhardt's brother, Manfred, was one of more than 5,000 children who were to suffer. | 0:43:38 | 0:43:45 | |

Manfred had been mentally disabled since birth. | 0:43:45 | 0:43:49 | |

But Aplerbeck was one of the Nazi's special children's units. | 0:44:43 | 0:44:48 | |

By now, two years after the policy had begun, | 0:44:48 | 0:44:53 | |

doctors in these homes had stopped filling in Buhler's form. In a typical example | 0:44:53 | 0:45:00 | |

of how policies could spiral away, | 0:45:00 | 0:45:03 | |

staff here, on their own, selected the children they wanted to kill. | 0:45:03 | 0:45:08 | |

The official record of deaths at Aplerbeck | 0:45:59 | 0:46:03 | |

lists Manfred Bernhardt as dying of measles on June 3rd. | 0:46:03 | 0:46:08 | |

In the same week, eleven other children died. | 0:46:08 | 0:46:13 | |

Manfred Bernhardt was murdered because he was not wanted in the Nazis' perfect state. | 0:46:15 | 0:46:22 | |

The catalyst that caused his death was a chance letter to Hitler on a subject close to his heart, | 0:46:22 | 0:46:29 | |

brought to his attention by an ambitious Nazi. | 0:46:29 | 0:46:34 | |

Any idea in this system | 0:46:34 | 0:46:37 | |

could, with the combination of a leader who spoke in visions, | 0:46:37 | 0:46:42 | |

and enthusiastic supporters anxious to please, | 0:46:42 | 0:46:46 | |

grow radically to an extreme almost in an instant. | 0:46:46 | 0:46:51 | |

This was the way Germany was ruled in the 1930s. | 0:46:53 | 0:46:57 | |

Now the world was about to suffer the consequences | 0:47:07 | 0:47:11 | |

of the radical way decisions were taken in this Hitler state. | 0:47:11 | 0:47:17 | |

Ceefax Subtitles by Janice Hamilton BBC Scotland, 1997 | 0:48:00 | 0:48:04 |