Crime and Punishment - The Story of Capital Punishment Timeshift

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Crime and Punishment - The Story of Capital Punishment. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Today, there are over 50 countries around the world which continue to use the death penalty. | 0:00:21 | 0:00:28 | |

Individuals who break the law can face a firing squad in China... | 0:00:28 | 0:00:32 | |

..lethal injection in the USA... | 0:00:34 | 0:00:37 | |

..and the hangman's noose in Singapore. | 0:00:38 | 0:00:40 | |

It is only a decade since capital punishment was finally removed from British law. | 0:00:46 | 0:00:50 | |

For centuries, Britain carried out state executions, | 0:00:51 | 0:00:55 | |

and capital punishment was defended as a deterrent against crime, | 0:00:55 | 0:01:01 | |

retribution against those who broke society's rules. | 0:01:01 | 0:01:05 | |

The noose would be put over their neck, | 0:01:07 | 0:01:09 | |

a hood put over their heads and then the cart would drive away, leaving them to dangle | 0:01:09 | 0:01:15 | |

and to gradually, slowly, after 30 minutes, to strangle to death. | 0:01:15 | 0:01:20 | |

For over 200 years, a moral battle raged | 0:01:22 | 0:01:26 | |

about whether the state has the right to execute. | 0:01:26 | 0:01:30 | |

A powerful liberal elite emerged, determined to abolish the death penalty. | 0:01:30 | 0:01:35 | |

The death penalty is inhuman and degrading when you see | 0:01:38 | 0:01:43 | |

how it is carried out and the procedures that are necessary. | 0:01:43 | 0:01:46 | |

But the vast majority of public opinion has continued to demand the ultimate punishment. | 0:01:49 | 0:01:55 | |

There are certain sorts of murder that are so premeditated, | 0:01:57 | 0:02:02 | |

so violent and so shocking, | 0:02:02 | 0:02:07 | |

that in the interests of maintaining confidence in the rule of law, | 0:02:07 | 0:02:11 | |

the only appropriate punishment is the death penalty. | 0:02:11 | 0:02:15 | |

This debate has shaped our ideas about how a civilised society | 0:02:15 | 0:02:20 | |

should punish its citizens in the 21st century. | 0:02:20 | 0:02:25 | |

The word "punishment" comes from the same root as "pain". | 0:02:26 | 0:02:31 | |

It is, in its essential conception, painful. | 0:02:31 | 0:02:35 | |

If it is not painful, it is not punishment. | 0:02:35 | 0:02:39 | |

The history of capital punishment in Britain is a long and bloody one. | 0:02:48 | 0:02:52 | |

Since the Middle Ages, those condemned to death have variously faced being boiled alive, | 0:02:52 | 0:02:58 | |

burnt at the stake, or hung, drawn and quartered. | 0:02:58 | 0:03:02 | |

But it was in the late 18th century that the death penalty was applied most widely. | 0:03:04 | 0:03:10 | |

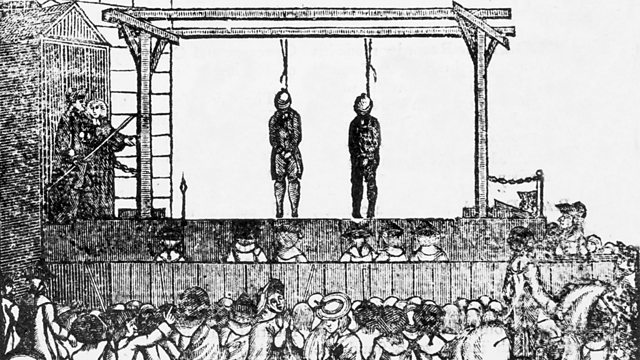

London, 1783 - thousands crammed the streets of the capital | 0:03:12 | 0:03:16 | |

to watch a public execution, carried out in the King's name. | 0:03:16 | 0:03:21 | |

This is the height of the Bloody Code, | 0:03:24 | 0:03:28 | |

a system of justice and punishment that listed over 200 offences | 0:03:28 | 0:03:32 | |

for which a man or a woman could be sent to the gallows. | 0:03:32 | 0:03:36 | |

In a society in which, | 0:03:37 | 0:03:38 | |

as they would have expressed it in those days, | 0:03:38 | 0:03:41 | |

they were lovers of liberty and very keen on property, | 0:03:41 | 0:03:46 | |

they had to have a means of protecting | 0:03:46 | 0:03:49 | |

both their liberty and property. | 0:03:49 | 0:03:51 | |

So you don't want a standing police force or a standing army | 0:03:51 | 0:03:54 | |

and therefore there was the very successful argument in Parliament | 0:03:54 | 0:03:59 | |

that you had capital punishment for just about everything. | 0:03:59 | 0:04:03 | |

Under the Bloody Code, even petty theft, | 0:04:04 | 0:04:07 | |

like pick-pocketing or stealing a sheep, | 0:04:07 | 0:04:10 | |

could result in the death penalty. | 0:04:10 | 0:04:13 | |

And it also threatened to execute anyone who kept the company of gypsies for more than a month... | 0:04:13 | 0:04:19 | |

or who blackened their face with the intention of stealing. | 0:04:19 | 0:04:23 | |

Because we have lost sight of its meaning to contemporaries | 0:04:26 | 0:04:30 | |

and we can reach only for one explanation - | 0:04:30 | 0:04:33 | |

that those people, 200, 300 years ago, | 0:04:33 | 0:04:35 | |

were barbarians, compared to us. | 0:04:35 | 0:04:38 | |

But go back to the 18th century and you have very few prisons, | 0:04:40 | 0:04:44 | |

very inefficient policing, but you do have the noose. | 0:04:44 | 0:04:48 | |

And the noose is understood, not as a cruel device, | 0:04:48 | 0:04:54 | |

but as a way of testifying to the anger of the King. | 0:04:54 | 0:04:58 | |

The execution day started at Newgate Prison, just west of St Paul's | 0:05:03 | 0:05:07 | |

in the centre of town | 0:05:07 | 0:05:09 | |

and the procession went from the gates of Newgate | 0:05:09 | 0:05:13 | |

through High Holborn, what is now modern Oxford Street, | 0:05:13 | 0:05:16 | |

on to the site of Tyburn. | 0:05:16 | 0:05:19 | |

From the Middle Ages, Tyburn had been the traditional site | 0:05:21 | 0:05:24 | |

of the majority of public executions in Britain. | 0:05:24 | 0:05:27 | |

The condemned would probably try and wear their best clothes, | 0:05:30 | 0:05:35 | |

some would put up a big brave show | 0:05:35 | 0:05:37 | |

and they would be taken along this route, | 0:05:37 | 0:05:40 | |

where people would either stand on the street, | 0:05:40 | 0:05:43 | |

or the better off would actually hire out rooms | 0:05:43 | 0:05:46 | |

on either side of the streets. | 0:05:46 | 0:05:48 | |

With no police force or prison system, capital punishment served as a deterrent against crime. | 0:05:51 | 0:05:57 | |

It was therefore important that everyone in society should attend, | 0:05:59 | 0:06:03 | |

to witness justice being carried out. | 0:06:03 | 0:06:06 | |

There was one occasion where a schoolteacher was reprimanded by the moral authorities, | 0:06:08 | 0:06:13 | |

probably by the local newspapers, because he decided to take his children on a picnic | 0:06:13 | 0:06:18 | |

so they wouldn't see the execution. | 0:06:18 | 0:06:19 | |

This was considered a very bad thing to do. | 0:06:19 | 0:06:22 | |

The trouble was, learning a moral lesson from the death of somebody else was what the moralists wanted. | 0:06:24 | 0:06:32 | |

It wasn't often what they got, because people would frequently | 0:06:32 | 0:06:36 | |

go along there in more of a party atmosphere. | 0:06:36 | 0:06:39 | |

The execution day had its own ritual, involving the participation of the crowd itself, | 0:06:42 | 0:06:48 | |

which appeared to revel in a macabre party atmosphere. | 0:06:48 | 0:06:51 | |

But some historians have interpreted this scene very differently. | 0:06:54 | 0:06:58 | |

It misses the silence that descends | 0:07:00 | 0:07:03 | |

when the executioner comes onto the platform. | 0:07:03 | 0:07:06 | |

When top hats came into fashion, | 0:07:08 | 0:07:11 | |

it misses the point of the big cry, "Hats off!" | 0:07:11 | 0:07:14 | |

It misses the kinds of communication that were possible | 0:07:16 | 0:07:20 | |

between members of the crowd and the felons about to die. | 0:07:20 | 0:07:26 | |

The jokes, the teasings, the cries from the crowd, "Hello, Curly! | 0:07:28 | 0:07:33 | |

"Keep up your spirits!" | 0:07:33 | 0:07:36 | |

Of course, the poor sod was actually shitting and pissing himself in sheer bloody terror. | 0:07:36 | 0:07:42 | |

Capital punishment as a deterrent was believed to work due to the painful nature of the executions. | 0:07:47 | 0:07:54 | |

Hangings often ended in a slow strangulation. | 0:07:54 | 0:07:58 | |

If they were lucky, their friends would pull on their legs to help end their misery. | 0:07:58 | 0:08:03 | |

This is the origin of the phrase "pulling your leg". | 0:08:06 | 0:08:10 | |

The watching crowd knew that a person's social class | 0:08:13 | 0:08:17 | |

would have determined whether they were executed. | 0:08:17 | 0:08:20 | |

One of the great defences of the death penalty was the idea that somehow, every aristocrat, | 0:08:22 | 0:08:27 | |

every member of the gentry was subject to the same laws. | 0:08:27 | 0:08:31 | |

In fact it's not true. It's self evidently not true. | 0:08:31 | 0:08:34 | |

99.9% of everybody who was executed by the state | 0:08:34 | 0:08:39 | |

was dirt poor and from the lowest class of Britain. | 0:08:39 | 0:08:44 | |

The vanishingly small number of aristocrats and members of the gentry | 0:08:44 | 0:08:48 | |

who ended their lives in execution, | 0:08:48 | 0:08:51 | |

did so by dint of being psychopaths and lunatics. | 0:08:51 | 0:08:54 | |

The accused faced trial by a jury drawn from the local community, | 0:08:58 | 0:09:03 | |

many of whom were sympathetic to the defendant's case. | 0:09:03 | 0:09:06 | |

Frequently, these juries sought to commute the punishment to avoid the death penalty. | 0:09:08 | 0:09:13 | |

Many juries, for example, refused to value property at their full value, | 0:09:15 | 0:09:21 | |

precisely in order to prevent a capital charge being applied in that particular case. | 0:09:21 | 0:09:26 | |

Juries also, regularly, um... | 0:09:26 | 0:09:30 | |

regularly pleaded for mercy, even after they'd found somebody guilty | 0:09:30 | 0:09:34 | |

and seen them sentenced to be hanged. | 0:09:34 | 0:09:39 | |

Between 1770 and 1830, over 35,000 people were sentenced to death, | 0:09:39 | 0:09:46 | |

but only one in ten were actually executed. | 0:09:46 | 0:09:50 | |

But the elite in society were indifferent to any notions of unequal justice. | 0:09:54 | 0:09:59 | |

They believed capital punishment worked as a deterrent. | 0:10:00 | 0:10:03 | |

And even enlightened thinkers of the time, such as the churchman and philosopher, William Paley, | 0:10:05 | 0:10:11 | |

were able to justify this, even if innocent people were executed. | 0:10:11 | 0:10:15 | |

When he was told that many people were hanged | 0:10:16 | 0:10:19 | |

who didn't deserve it or who might even be innocent, | 0:10:19 | 0:10:24 | |

"Oh!" he said, in a very fine language, of course, | 0:10:24 | 0:10:28 | |

"So what? These people may be deemed to have hanged for England!" | 0:10:28 | 0:10:34 | |

In other words, their deaths were part of the price we had to pay | 0:10:34 | 0:10:39 | |

for social order and deference to the established hierarchy. | 0:10:39 | 0:10:45 | |

This view was supported by the work of German philosopher Immanuel Kant, | 0:10:47 | 0:10:53 | |

who argued that even in a civilised society, | 0:10:53 | 0:10:56 | |

the state had the right to punish the individual. | 0:10:56 | 0:11:00 | |

For Kant, the only purely evil thing is an evil will, | 0:11:01 | 0:11:04 | |

so you measure the seriousness of the crime | 0:11:04 | 0:11:08 | |

by the attitude of the criminal. | 0:11:08 | 0:11:10 | |

For Kant, the death penalty was a moral imperative. | 0:11:10 | 0:11:14 | |

It was a duty, but it was to be done without any emotion. | 0:11:14 | 0:11:18 | |

We did it as a matter of duty. | 0:11:18 | 0:11:20 | |

And, in fact, we celebrate human dignity by executing them, | 0:11:22 | 0:11:25 | |

by saying, "You are a responsible agent. | 0:11:25 | 0:11:28 | |

"You chose to do what you did, and you deserve to die for it. | 0:11:28 | 0:11:32 | |

"We will not look at you as a means to deter others from committing crimes." | 0:11:32 | 0:11:37 | |

He firmly believed that you never use a person as a means to your ends. | 0:11:38 | 0:11:43 | |

Human beings are ends in themselves. | 0:11:43 | 0:11:46 | |

Kant's ideas continued to influence the debate about punishment | 0:11:50 | 0:11:54 | |

into the 19th century and a new Victorian era. | 0:11:54 | 0:11:57 | |

But by the 1830s, the election of the Whigs into government brought a new reforming agenda. | 0:12:01 | 0:12:08 | |

The Reform Act famously gives the vote to the middle classes, | 0:12:12 | 0:12:16 | |

but also a lot of the statutes on the Bloody Code are repealed, | 0:12:16 | 0:12:21 | |

so that by the end of the 1830s, you can hang really only for murder. | 0:12:21 | 0:12:27 | |

Despite this new age of reform, the Victorians were still committed | 0:12:30 | 0:12:34 | |

to retaining the death penalty for those convicted of murder. | 0:12:34 | 0:12:37 | |

But for other, lesser crimes, they wanted a more proportional punishment that fitted the crime, | 0:12:40 | 0:12:46 | |

so a sheep stealer would no longer be treated the same as a murderer. | 0:12:46 | 0:12:51 | |

Punishment ought to be not only proportional, | 0:12:52 | 0:12:57 | |

but by being proportional to the offence, rational. | 0:12:57 | 0:13:01 | |

Measurement, proportionality is one big idea that begins to unseat | 0:13:01 | 0:13:07 | |

the old system that had, of course, gone back for centuries. | 0:13:07 | 0:13:11 | |

Dismantling the Bloody Code had an immediate effect on the Victorian justice system. | 0:13:13 | 0:13:19 | |

Now, juries were more likely to convict in the knowledge that the death penalty no longer applied. | 0:13:19 | 0:13:25 | |

They eliminated capital punishment from rape in 1842 | 0:13:27 | 0:13:32 | |

and what happened afterwards is that the conviction rate went straight through the roof. | 0:13:32 | 0:13:37 | |

It went from a modern equivalent of 5% convictions, | 0:13:37 | 0:13:42 | |

to between 13% and 18% conviction rate, | 0:13:42 | 0:13:45 | |

simply because they changed the nature of the punishment associated with that particular crime. | 0:13:45 | 0:13:50 | |

But as conviction rates soared, so too did the Victorians' fear of crime. | 0:13:53 | 0:13:58 | |

This fear came from the presence of a new mass urban population, | 0:13:58 | 0:14:03 | |

which, during the Industrial Revolution, | 0:14:03 | 0:14:06 | |

had migrated to Britain's cities in their thousands. | 0:14:06 | 0:14:09 | |

As you start to have very large numbers of very poor people, | 0:14:09 | 0:14:14 | |

crowded into districts together, | 0:14:14 | 0:14:16 | |

society's becoming much more concerned about criminality, | 0:14:16 | 0:14:20 | |

about the possibility of a criminal underclass, | 0:14:20 | 0:14:23 | |

about the consequences of having so many poor people congregated in very small areas. | 0:14:23 | 0:14:28 | |

One of the other things happening in the early 19th century is | 0:14:28 | 0:14:31 | |

for the first time the government is collecting figures | 0:14:31 | 0:14:34 | |

as to how many people are brought before the courts, | 0:14:34 | 0:14:36 | |

and again, the figures always seem to go up | 0:14:36 | 0:14:38 | |

and of course, we know now the population is rising anyway. | 0:14:38 | 0:14:41 | |

The figures are going up so this helps to contribute to this fear of crime | 0:14:41 | 0:14:46 | |

which is really starting to emerge in the early 19th century. | 0:14:46 | 0:14:49 | |

In 1862, there is a moral panic about mugging | 0:14:49 | 0:14:54 | |

that is precipitated in the newspapers by one solitary event, | 0:14:54 | 0:14:59 | |

when an MP called Pilkington was mugged by a garrotter. | 0:14:59 | 0:15:05 | |

With conviction rates rising, but fewer crimes subject to the death penalty, | 0:15:09 | 0:15:14 | |

the Victorians searched for new ideas about punishment. | 0:15:14 | 0:15:18 | |

Up until now, local jails had just held prisoners before they were punished. | 0:15:19 | 0:15:25 | |

But into the 1840s, as part of a wider expansion of the state | 0:15:26 | 0:15:31 | |

and the ending of transportation as a sentencing option, | 0:15:31 | 0:15:35 | |

the Victorians began to build large prisons across Britain | 0:15:35 | 0:15:39 | |

as places of both punishment and reform. | 0:15:39 | 0:15:43 | |

A new idea of prison, where you have the ordered prisons, | 0:15:44 | 0:15:47 | |

with the sexes separated, different kinds of criminals classified, | 0:15:47 | 0:15:51 | |

being made to perform useful work as part of their punishment, | 0:15:51 | 0:15:55 | |

all in a specially designed building, set apart from the rest of the community. | 0:15:55 | 0:16:00 | |

But those convicted of murder still faced a public execution... | 0:16:03 | 0:16:07 | |

..which, by the mid Victorian era, was coming under attack from an educated elite. | 0:16:09 | 0:16:14 | |

You got prominent publicists as well, | 0:16:16 | 0:16:19 | |

Dickens and Thackeray being probably being the most prominent, | 0:16:19 | 0:16:23 | |

who both attended public executions and both wrote about them. | 0:16:23 | 0:16:27 | |

Both of them were appalled by the behaviour of the people. | 0:16:27 | 0:16:31 | |

"It was so loathsome, pitiful and vile a sight, | 0:16:31 | 0:16:34 | |

"I did not see one token, in all the immense crowd, | 0:16:34 | 0:16:38 | |

"at the windows, in the streets, | 0:16:38 | 0:16:40 | |

"on the housetops, anywhere, | 0:16:40 | 0:16:42 | |

"of any one emotion suitable to the occasion. | 0:16:42 | 0:16:47 | |

"No sorrow, no terror, no abhorrence, no seriousness - | 0:16:47 | 0:16:51 | |

"nothing but ribaldry, debauchery, levity, drunkenness and flaunting vice." | 0:16:51 | 0:16:57 | |

The public execution is almost a way of saying aggression and violence is acceptable and tolerable | 0:16:57 | 0:17:03 | |

and is promoted by the state and this is the very last thing the Victorians want. | 0:17:03 | 0:17:07 | |

They've got a kind of civilising idea. | 0:17:07 | 0:17:09 | |

It was this disgust at the scene of a public execution | 0:17:11 | 0:17:14 | |

that led to the first real movement to abolish the death penalty. | 0:17:14 | 0:17:19 | |

By the 1840s, there's a really very serious movement | 0:17:21 | 0:17:26 | |

for total abolition of capital punishment in England | 0:17:26 | 0:17:30 | |

that pulls in people like Thackeray. | 0:17:30 | 0:17:33 | |

The argument being that we have other ways of controlling order, | 0:17:34 | 0:17:40 | |

so that we do not need to resort to the sledgehammer control delivered by the noose. | 0:17:40 | 0:17:47 | |

But the vast majority of the population were convinced | 0:17:47 | 0:17:51 | |

that the death penalty should be retained, | 0:17:51 | 0:17:54 | |

and this view was openly supported by the Church of England. | 0:17:54 | 0:17:58 | |

Now capital punishment is a peculiar punishment, because it was justified specifically on biblical terms. | 0:18:00 | 0:18:07 | |

All the arguments were to do with the Bible. | 0:18:07 | 0:18:10 | |

After all, fines, or community service, | 0:18:10 | 0:18:13 | |

or even being put in the stocks don't actually appear in the Bible. | 0:18:13 | 0:18:16 | |

They have killed the image of God, another human being, | 0:18:18 | 0:18:23 | |

and so they will be killed themselves | 0:18:23 | 0:18:26 | |

and that was accepted by practically everyone. | 0:18:26 | 0:18:30 | |

Convinced that the death penalty was sanctioned by God, | 0:18:32 | 0:18:36 | |

the Victorians turned to the newly built prisons to solve the debate over public executions. | 0:18:36 | 0:18:42 | |

It was one of the suggestions of Bishop Wilberforce | 0:18:44 | 0:18:47 | |

that we've got these wonderful prisons, | 0:18:47 | 0:18:50 | |

why don't we put capital punishment into a prison? | 0:18:50 | 0:18:54 | |

In 1868, the last public execution was carried out on British soil. | 0:18:57 | 0:19:03 | |

Michael Barrett, an Irish Republican, | 0:19:03 | 0:19:06 | |

was hanged outside Newgate Prison | 0:19:06 | 0:19:09 | |

while the crowds sang a popular music hall tune, Champagne Charlie. | 0:19:09 | 0:19:13 | |

By moving the gallows into the prison, | 0:19:19 | 0:19:21 | |

the authorities also wanted to introduce a more official and systematic way of killing | 0:19:21 | 0:19:27 | |

which would be carried out by professional hangmen. | 0:19:27 | 0:19:31 | |

But you had the rise of regular hangmen, | 0:19:34 | 0:19:37 | |

one of the things they could do - | 0:19:37 | 0:19:39 | |

and this was developed in a very systematic way - | 0:19:39 | 0:19:42 | |

was they could take the weights and measurements of the person they were going to kill. | 0:19:42 | 0:19:47 | |

They would view them in a prison cell through a loophole | 0:19:47 | 0:19:51 | |

so they could gauge, this person's stocky, this person's thin, this person's 5 foot 3 or whatever. | 0:19:51 | 0:19:57 | |

There were scales and measurements by which you could then judge | 0:19:58 | 0:20:02 | |

how much rope you would use and the quality of the rope. | 0:20:02 | 0:20:06 | |

That would ensure that you neither made it too long, | 0:20:06 | 0:20:10 | |

in which case you might decapitate the person, | 0:20:10 | 0:20:13 | |

or too short, in which case you might strangle the person. | 0:20:13 | 0:20:17 | |

Just the right length should lead to instantaneous death. | 0:20:17 | 0:20:21 | |

Hangmen were now expected to carry out their duties in an orderly and responsible fashion. | 0:20:28 | 0:20:33 | |

One of the concerns that the Home Office had | 0:20:35 | 0:20:38 | |

was the amount of drinking that the executioners used to engage in | 0:20:38 | 0:20:43 | |

and so that was restricted. | 0:20:43 | 0:20:47 | |

From then on, they had to spend the night in the prison before the hanging | 0:20:47 | 0:20:52 | |

and they were only allowed a quarter of a pint of spirits | 0:20:52 | 0:20:56 | |

and a couple of pints of ale the night before. | 0:20:56 | 0:21:00 | |

So it was all much more dignified. | 0:21:00 | 0:21:03 | |

This move towards a dignified system of capital punishment | 0:21:05 | 0:21:09 | |

silenced those voices who had called for the abolition of the public execution. | 0:21:09 | 0:21:14 | |

And once it is proposed to hide the executions in the prison, | 0:21:19 | 0:21:25 | |

the argument is won for sustaining capital punishment | 0:21:25 | 0:21:29 | |

all the way through to the '60s. So it is a key moment. | 0:21:29 | 0:21:33 | |

Had there not been a solution to the problem of the crowd found in the hiding of executions, | 0:21:35 | 0:21:41 | |

the whole thing might have collapsed much earlier than it did. | 0:21:41 | 0:21:44 | |

The Victorian era saw a major shift in how a modern civilised society | 0:21:53 | 0:21:58 | |

maintains order and administers punishment. | 0:21:58 | 0:22:01 | |

The great transformation of punishment in the modern era | 0:22:03 | 0:22:07 | |

moved its locus from the body to the personality. | 0:22:07 | 0:22:12 | |

That is, originally punishment was the infliction of pain and suffering on the body, | 0:22:12 | 0:22:19 | |

and then the Enlightenment came along | 0:22:19 | 0:22:21 | |

and the Enlightenment embraced the idea of human beings as rational. | 0:22:21 | 0:22:27 | |

And instead of inflicting pain and suffering on the body, | 0:22:27 | 0:22:30 | |

we took the great good not to be so much life, as liberty, | 0:22:30 | 0:22:35 | |

so that we now correlate the heinousness of the crime | 0:22:35 | 0:22:39 | |

with a degree of loss of liberty | 0:22:39 | 0:22:42 | |

and instead of inflicting pain and suffering directly on the body, | 0:22:42 | 0:22:46 | |

what we do is deprive people of rights. | 0:22:46 | 0:22:49 | |

For the next 60 years, it appeared that those who supported capital punishment had won the debate. | 0:22:58 | 0:23:04 | |

# Hangman, hangman Hold it a little while | 0:23:05 | 0:23:10 | |

# I think I seen my friends coming | 0:23:10 | 0:23:14 | |

# Riding many a mile... # | 0:23:14 | 0:23:17 | |

Into the first half of the 20th century, | 0:23:17 | 0:23:20 | |

executions continued inside the walls of Britain's prisons, | 0:23:20 | 0:23:24 | |

without any significant opposition. | 0:23:24 | 0:23:26 | |

# What did you bring me my dear friends | 0:23:26 | 0:23:29 | |

# To keep me from the gallows pole? # | 0:23:29 | 0:23:31 | |

While public opinion remained solidly in favour, | 0:23:33 | 0:23:37 | |

only a handful of eccentrics, like the heiress Violet Van Der Elst, | 0:23:37 | 0:23:42 | |

campaigned against the death penalty. | 0:23:42 | 0:23:44 | |

Well, Mrs Van Der Elst was one of those curious figures | 0:23:44 | 0:23:48 | |

in capital punishment, because she was a classic eccentric Englishwoman. | 0:23:48 | 0:23:52 | |

She inherited a lot of money and she decided | 0:23:52 | 0:23:56 | |

not to take up the cause of cats and dogs, | 0:23:56 | 0:23:59 | |

but to take up the cause of capital punishment. | 0:23:59 | 0:24:03 | |

And because of her money and her sense of stage management, | 0:24:03 | 0:24:10 | |

she could ensure big displays wherever she went. | 0:24:10 | 0:24:14 | |

So, for instance, when executions were taking place in prisons, | 0:24:14 | 0:24:18 | |

she would drive up to the prison in a Rolls-Royce. | 0:24:18 | 0:24:21 | |

So she was much more difficult for the authorities to handle, | 0:24:21 | 0:24:24 | |

because you couldn't just sort of knock her out of the way - | 0:24:24 | 0:24:27 | |

A) she was a woman, B) she's rich | 0:24:27 | 0:24:30 | |

C) she's sort of rich and well connected | 0:24:30 | 0:24:32 | |

and she's in a Rolls-Royce! | 0:24:32 | 0:24:34 | |

In some ways, of course, she was a person that proponents of capital punishment could point to and say, | 0:24:36 | 0:24:43 | |

"Well, it's lunatics who are really concerned about this sort of thing." | 0:24:43 | 0:24:47 | |

Kept from view by the authorities, capital punishment was now largely beneath the public's radar. | 0:24:51 | 0:24:57 | |

But this would change in the aftermath of the Second World War. | 0:24:57 | 0:25:02 | |

By executing Nazi war criminals, Britain and its wartime allies | 0:25:03 | 0:25:08 | |

were exacting a visual show of justice. | 0:25:08 | 0:25:11 | |

Over 200 of these executions were carried out by a British hangman, | 0:25:18 | 0:25:22 | |

Albert Pierrepoint, | 0:25:22 | 0:25:25 | |

whose deployment to Germany propelled him into the spotlight. | 0:25:25 | 0:25:29 | |

Of course, in the early part of the 20th century, | 0:25:29 | 0:25:31 | |

the hangman, the executioner, had been an obscure figure. | 0:25:31 | 0:25:35 | |

He was an agent of the state. His identity was covered up. | 0:25:35 | 0:25:38 | |

What made Albert Pierrepoint a celebrity | 0:25:38 | 0:25:41 | |

was not executing people in the 1930s, | 0:25:41 | 0:25:43 | |

it's when he goes off to Nuremburg at the end of the Second World War | 0:25:43 | 0:25:46 | |

and he executes all these Nazi war criminals. | 0:25:46 | 0:25:49 | |

And the press sort of dig and find out his identity | 0:25:49 | 0:25:52 | |

and he becomes a celebrity, because he's, oddly, | 0:25:52 | 0:25:55 | |

a kind of patriotic icon, one of our boys, | 0:25:55 | 0:25:58 | |

who's had the last word in the war by stringing up all these awful Nazis. | 0:25:58 | 0:26:03 | |

That's the way it's presented. | 0:26:03 | 0:26:04 | |

And Pierrepoint then becomes the first and only modern executioner celebrity. | 0:26:04 | 0:26:10 | |

Pierrepoint became a familiar face to British audiences through numerous television interviews. | 0:26:11 | 0:26:18 | |

You always get a new rope and an old rope. | 0:26:19 | 0:26:22 | |

Well, we always choose the old rope if we can, | 0:26:22 | 0:26:24 | |

because a new rope, it seems to lash back. You see what I mean? | 0:26:24 | 0:26:29 | |

The springing of it, you see? | 0:26:29 | 0:26:31 | |

If you get an old one that's been used before - | 0:26:31 | 0:26:33 | |

you've got to examine it well before you use it - | 0:26:33 | 0:26:35 | |

and you leave it with a sandbag on that, the same weight, hanging overnight, | 0:26:35 | 0:26:40 | |

you see? It's all prepared for morning then. | 0:26:40 | 0:26:44 | |

There's a kind of macabre fascination to him, and the reason you have that | 0:26:46 | 0:26:50 | |

is I think because the concept of executing people | 0:26:50 | 0:26:53 | |

has become so detached from people's ordinary lives. | 0:26:53 | 0:26:56 | |

In a very ordered, settled, consensual society, | 0:26:56 | 0:26:59 | |

to be the person who actually carries out the sentence | 0:26:59 | 0:27:02 | |

has this kind of weird exoticism to it and I think that's why he became such a public name. | 0:27:02 | 0:27:09 | |

Did it matter how you attached the rope? | 0:27:09 | 0:27:11 | |

Oh, yes, there's a certain way in doing it... | 0:27:11 | 0:27:14 | |

to be instantaneous, yes, very definitely. | 0:27:14 | 0:27:18 | |

It has on the rope, at the end of a rope, a brass... | 0:27:18 | 0:27:24 | |

brass ring, like, and the rope goes through that, you see, | 0:27:24 | 0:27:28 | |

and you put that under the left jaw, | 0:27:28 | 0:27:30 | |

so when he falls and stops dead, it finishes under the chin... | 0:27:30 | 0:27:34 | |

should finish under the chin as he throws his head back, and breaks the spinal cord. | 0:27:34 | 0:27:39 | |

The British public may have supported the Nuremburg executions, | 0:27:48 | 0:27:53 | |

but by the 1950s, there was increasing disquiet at the continued use of the death penalty. | 0:27:53 | 0:27:59 | |

In 1953, this unease was evident in the case of Derek Bentley. | 0:28:00 | 0:28:07 | |

Bentley, along with his accomplice, Christopher Craig, | 0:28:11 | 0:28:14 | |

were stealing from a warehouse | 0:28:14 | 0:28:17 | |

when they were confronted by the police. | 0:28:17 | 0:28:19 | |

Craig fled, but Bentley was arrested | 0:28:19 | 0:28:22 | |

and was alleged to have shouted, "Let him have it!" | 0:28:22 | 0:28:26 | |

moments before Craig shot dead PC Sidney Miles. | 0:28:26 | 0:28:30 | |

As Craig was only 16, Bentley would hang for the murder. | 0:28:30 | 0:28:34 | |

It also transpired | 0:28:37 | 0:28:38 | |

that Derek Bentley had a mental age of something like 11, | 0:28:38 | 0:28:44 | |

that he came from a rather disturbed background. | 0:28:44 | 0:28:48 | |

These facts were withheld from the jury at the trial. | 0:28:48 | 0:28:52 | |

He had certainly not been the leader in this enterprise | 0:28:52 | 0:28:58 | |

of breaking into this warehouse. | 0:28:58 | 0:29:02 | |

He'd been easily captured by the police | 0:29:02 | 0:29:05 | |

and the police simply said that he had shouted out to Craig | 0:29:05 | 0:29:09 | |

as he came up onto the roof, "Let him have it!" | 0:29:09 | 0:29:13 | |

That was much disputed. | 0:29:13 | 0:29:15 | |

The case rested on the prosecution's assumption that "Let him have it!" | 0:29:16 | 0:29:21 | |

was an encouragement to shoot the policeman, not to hand the gun over. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:25 | |

But many of the public disagreed with this interpretation. | 0:29:26 | 0:29:30 | |

And there was even doubt that he had said this at all. | 0:29:32 | 0:29:35 | |

I think everybody thought that he would be reprieved, | 0:29:38 | 0:29:41 | |

and when he wasn't reprieved, there was a great deal of public concern, | 0:29:41 | 0:29:45 | |

both in the press, but also by people going along to the prison in the morning | 0:29:45 | 0:29:49 | |

and creating a large demonstration. | 0:29:49 | 0:29:52 | |

The apparent injustice led to some public sympathy for Bentley | 0:29:54 | 0:29:59 | |

and to a questioning of the state's right to execute a mandatory death sentence... | 0:29:59 | 0:30:04 | |

..on a vulnerable individual. | 0:30:05 | 0:30:08 | |

I think what that demonstrated | 0:30:11 | 0:30:13 | |

was that, to have a system in which the death penalty was mandatory for murder | 0:30:13 | 0:30:20 | |

and in which everything, every way of trying to classify murders | 0:30:20 | 0:30:26 | |

as those that were death worthy or not death worthy | 0:30:26 | 0:30:29 | |

came down to a political decision of the Secretary of State. | 0:30:29 | 0:30:33 | |

That particular Secretary of State decided that he would not act in favour of Derek Bentley, | 0:30:33 | 0:30:39 | |

so there seemed to be a gross unfairness in the case. | 0:30:39 | 0:30:42 | |

Bentley's case caught the public's attention through its coverage in the press. | 0:30:44 | 0:30:49 | |

Through the 1950s, capital punishment | 0:30:51 | 0:30:53 | |

began to be openly debated on the pages of the nation's newspapers. | 0:30:53 | 0:30:57 | |

Britain had one of the highest rates of newspaper readership in the world | 0:30:59 | 0:31:03 | |

and there's enormous competition between The People, | 0:31:03 | 0:31:07 | |

The News of the World, The Mirror, The Mail, The Express and so on, | 0:31:07 | 0:31:11 | |

and they used those classic kind of Victorian staples | 0:31:11 | 0:31:15 | |

of sex and sensation and murder and whatnot, to sell copies. | 0:31:15 | 0:31:19 | |

In 1955, the press seized on the story of Ruth Ellis, | 0:31:22 | 0:31:27 | |

a young woman sentenced to hang for the murder of her lover. | 0:31:27 | 0:31:32 | |

We have to say there's an element of interest in the fact that it was | 0:31:35 | 0:31:39 | |

an attractive woman, that it was a crime of passion, so called. | 0:31:39 | 0:31:44 | |

She wasn't necessarily a sympathetic person, | 0:31:44 | 0:31:47 | |

in those times when promiscuity was decried even more than today. | 0:31:47 | 0:31:53 | |

She'd had a couple of lovers, she had two children. | 0:31:53 | 0:31:56 | |

There was quite a bit of concern that she just didn't shoot him once, but several times. | 0:31:56 | 0:32:01 | |

But there was a degree of public empathy for Ruth Ellis. | 0:32:06 | 0:32:09 | |

Like the Bentley case two years earlier, people questioned whether | 0:32:09 | 0:32:14 | |

this "crime of passion" should carry a mandatory death sentence. | 0:32:14 | 0:32:19 | |

The idea that a distraught woman acting in a passionate moment | 0:32:23 | 0:32:28 | |

would go to the gallows, I think, caught the public imagination | 0:32:28 | 0:32:33 | |

and made people question whether that was the right thing to be doing to a young woman. | 0:32:33 | 0:32:39 | |

BELL TOLLS | 0:32:41 | 0:32:45 | |

That raised the further question, if it was not right to do it to young women, | 0:32:46 | 0:32:52 | |

was it right to do it to young men? | 0:32:52 | 0:32:54 | |

And so I think the debate, if you look at the papers, | 0:32:54 | 0:32:59 | |

I think she is... and the way her case was treated, | 0:32:59 | 0:33:03 | |

was the catalyst for what would later become a campaign. | 0:33:03 | 0:33:08 | |

Both Bentley and Ellis were hanged | 0:33:09 | 0:33:12 | |

by Britain's chief executioner, Albert Pierrepoint. | 0:33:12 | 0:33:15 | |

Such was the controversial nature of the Ellis and Bentley cases, | 0:33:17 | 0:33:22 | |

that in 1957, the Conservative Government passed the Homicide Act | 0:33:22 | 0:33:27 | |

which introduced the new defences | 0:33:27 | 0:33:29 | |

of provocation and diminished responsibility for murder. | 0:33:29 | 0:33:34 | |

So they brought in that some murders would be | 0:33:36 | 0:33:39 | |

capital murders - what the Americans call first-degree murders, | 0:33:39 | 0:33:43 | |

capital murders, and other murders - | 0:33:43 | 0:33:46 | |

the pub fight, the domestic dispute, or whatever, would not be. | 0:33:46 | 0:33:51 | |

This law resulted in fewer executions, | 0:33:53 | 0:33:57 | |

with only five or six people a year being sent to the gallows. | 0:33:57 | 0:34:01 | |

But the Homicide Act caused confusion. | 0:34:02 | 0:34:05 | |

-NEWSREEL: -'We don't know why some are hanged and some reprieved. | 0:34:07 | 0:34:10 | |

'One Sunday newspaper posed this question and gave these examples. | 0:34:10 | 0:34:13 | |

'Francis Forsyth, 18, murdered Alan Gee as he was walking home. | 0:34:13 | 0:34:19 | |

'He robbed him and kicked him unconscious with his pointed shoes. | 0:34:19 | 0:34:22 | |

'Forsyth was executed. | 0:34:22 | 0:34:23 | |

'But David Deduchar, 21, did much the same thing. | 0:34:23 | 0:34:28 | |

'He battered an old man to death and stole his wallet. | 0:34:28 | 0:34:30 | |

'Deduchar was reprieved.' | 0:34:30 | 0:34:33 | |

Those sort of anomalies convinced quite a lot of people, | 0:34:34 | 0:34:38 | |

including members of the judiciary, | 0:34:38 | 0:34:40 | |

which was the other change that really took place in the '50s and early '60s, | 0:34:40 | 0:34:46 | |

you actually got members of the judiciary thinking that this just wasn't going to work any more. | 0:34:46 | 0:34:53 | |

The debate over capital punishment peaked in December 1964, | 0:34:58 | 0:35:03 | |

when a Labour MP, Sidney Silverman, submitted a Private Member's Bill to Parliament. | 0:35:03 | 0:35:08 | |

Silverman's bill proposed an experiment - the suspension of all executions for five years. | 0:35:10 | 0:35:16 | |

On 21st December 1964, as Parliament debated this bill, | 0:35:16 | 0:35:22 | |

the BBC screened a live debate | 0:35:22 | 0:35:25 | |

between proponents of capital punishment and abolitionists. | 0:35:25 | 0:35:30 | |

In two-and-a-half hours from now, we shall know whether or not | 0:35:31 | 0:35:36 | |

hanging for murder is likely to be abolished in Great Britain. | 0:35:36 | 0:35:39 | |

At this moment, the House of Commons is locked in debate on capital punishment. | 0:35:39 | 0:35:44 | |

There will be a free vote at 11 o'clock. | 0:35:44 | 0:35:46 | |

But I believe this particular penalty for particular people, | 0:35:46 | 0:35:51 | |

namely professional criminals, is the one real deterrent. | 0:35:51 | 0:35:56 | |

That argument about deterrence is the standard argument | 0:35:56 | 0:35:59 | |

that has been put for 150 years in respect of every form | 0:35:59 | 0:36:02 | |

of capital punishment and has always been proved wrong. | 0:36:02 | 0:36:05 | |

Astonishing, that Henry Rook should bring testimony today | 0:36:05 | 0:36:07 | |

to say that he's now convinced | 0:36:07 | 0:36:09 | |

that that particular argument cannot be borne out... | 0:36:09 | 0:36:14 | |

Later that evening, Sidney Silverman's bill was passed by 200 votes to 98. | 0:36:14 | 0:36:21 | |

But it didn't reflect public opinion on the issue. | 0:36:23 | 0:36:25 | |

Despite much sympathy for cases like Bentley and Ellis, | 0:36:27 | 0:36:31 | |

there was still widespread support for capital punishment. | 0:36:31 | 0:36:34 | |

In polls in the 1960s, people said | 0:36:36 | 0:36:38 | |

the one thing about the whole of the 1960s that they disliked most | 0:36:38 | 0:36:41 | |

was the abolition of the death penalty. | 0:36:41 | 0:36:43 | |

So what you have effectively is an elite driven, | 0:36:43 | 0:36:48 | |

kind of liberal establishment project to reform the death penalty. | 0:36:48 | 0:36:53 | |

That comes from education and from a different moral outlook and whatnot, | 0:36:53 | 0:36:58 | |

but it also rests on something that we simply don't have today, | 0:36:58 | 0:37:02 | |

which is a sense that the people in Parliament know better. They know best! | 0:37:02 | 0:37:07 | |

And they are not dependant on the kind of popular will, if you like, | 0:37:07 | 0:37:11 | |

on popular opinion for their mandate. | 0:37:11 | 0:37:14 | |

So, in a funny way, the abolition of the death penalty would be impossible in today's Parliament. | 0:37:14 | 0:37:19 | |

It was something only possible in the '50s and '60s, | 0:37:19 | 0:37:22 | |

because they didn't have that kind of populist, political culture that we have today. | 0:37:22 | 0:37:26 | |

Despite Parliament's ruling, the debate over capital punishment | 0:37:29 | 0:37:32 | |

continued to rage throughout the 1960s. | 0:37:32 | 0:37:35 | |

And they were expecting that if you could abolish it at Parliament, | 0:37:38 | 0:37:42 | |

that you could also bring it back through Parliament. | 0:37:42 | 0:37:45 | |

So naturally enough, any high-profile case, | 0:37:45 | 0:37:50 | |

especially one which might, as it were, lead to at least bringing it back partially, | 0:37:50 | 0:37:56 | |

say for the murder of policemen, or for a particularly violent set of murders. | 0:37:56 | 0:38:01 | |

These were leapt on by newspapers in order to try and reverse the decision. | 0:38:01 | 0:38:06 | |

In October 1965, less than a year after abolition, | 0:38:08 | 0:38:13 | |

the resolve of Parliament would be tested by one of the most notorious murder cases of the 20th century. | 0:38:13 | 0:38:20 | |

We think of the mid '60s as this great utopian, happy-go-lucky, | 0:38:22 | 0:38:26 | |

kind of orgiastic age where everyone is having a great time. | 0:38:26 | 0:38:30 | |

In fact, the mid '60s was a much more anxious, darker time than we remember. | 0:38:30 | 0:38:35 | |

In what would become known as the Moors Murders, | 0:38:36 | 0:38:40 | |

Ian Brady and Myra Hindley kidnapped, | 0:38:40 | 0:38:43 | |

tortured and killed five children, | 0:38:43 | 0:38:46 | |

burying them in shallow graves on Saddleworth Moor. | 0:38:46 | 0:38:49 | |

-REPORTER: -On these bleak and desolate moorlands, | 0:38:50 | 0:38:53 | |

1,600ft up in the Pennines, senior police officers believe | 0:38:53 | 0:38:57 | |

they'll find two more bodies, possibly a third. | 0:38:57 | 0:39:01 | |

It's impossible to overstate how shocking those crimes were, | 0:39:03 | 0:39:07 | |

particularly when the tapes were played in court, | 0:39:07 | 0:39:09 | |

then reported in the newspapers. | 0:39:09 | 0:39:11 | |

At their trial, there was public outrage | 0:39:12 | 0:39:15 | |

when a tape recording was played to the court | 0:39:15 | 0:39:17 | |

of Brady and Hindley torturing 10-year-old Leslie Ann Downey. | 0:39:17 | 0:39:22 | |

And that means that within a year of the suspension of the death penalty, | 0:39:25 | 0:39:29 | |

you have newspaper columnists and particularly people in the pub, | 0:39:29 | 0:39:32 | |

people on the street corners, or whatnot, | 0:39:32 | 0:39:35 | |

calling for the death penalty to be brought back, because if there are kind of two people | 0:39:35 | 0:39:39 | |

who to people in he 1960s seem ideal candidates for the hangman's noose, | 0:39:39 | 0:39:44 | |

it's Brady and Hindley. | 0:39:44 | 0:39:46 | |

The overwhelming majority wanted to see Brady and Hindley hang for their crimes. | 0:39:48 | 0:39:54 | |

But public pressure could not convince the government. | 0:39:58 | 0:40:01 | |

Brady and Hindley were both sentenced to life imprisonment. | 0:40:01 | 0:40:06 | |

A life sentence for murder was now mandatory, | 0:40:09 | 0:40:11 | |

following the suspension of the death penalty in 1965. | 0:40:11 | 0:40:16 | |

The mandatory life sentence was brought in | 0:40:18 | 0:40:20 | |

as a condition of abolishing the death penalty. | 0:40:20 | 0:40:24 | |

Those who opposed abolition were told by those who advocated it | 0:40:24 | 0:40:28 | |

and who in the end prevailed | 0:40:28 | 0:40:30 | |

that they would always be safeguarded, because there would be this mandatory life sentence. | 0:40:30 | 0:40:34 | |

The mandatory life sentence was aimed at extending | 0:40:36 | 0:40:39 | |

the amount of time a convicted murderer could be in prison for. | 0:40:39 | 0:40:43 | |

In the days of capital punishment, those reprieved - | 0:40:45 | 0:40:50 | |

and that was the majority of murderers who were reprieved - | 0:40:50 | 0:40:55 | |

served sentences considerably lower than they would serve today, | 0:40:55 | 0:41:00 | |

despite the media thinking we are soft on crime. | 0:41:00 | 0:41:04 | |

Craig, who couldn't be sentenced to the hangman because of his age, | 0:41:04 | 0:41:09 | |

when Bentley was executed, served 11 or 12 years | 0:41:09 | 0:41:13 | |

for the shooting of a police officer. | 0:41:13 | 0:41:17 | |

Now, even as a 16-year-old, he would probably serve a minimum of 25. | 0:41:17 | 0:41:22 | |

So the sentence doubled! | 0:41:22 | 0:41:24 | |

In fact, under today's tariff system, | 0:41:26 | 0:41:29 | |

some prisoners serving life sentences are eligible for early parole. | 0:41:29 | 0:41:34 | |

But this raises its own moral questions about | 0:41:34 | 0:41:37 | |

how the state punishes individuals, like Harry Roberts, | 0:41:37 | 0:41:41 | |

who's been locked up for 44 years, | 0:41:41 | 0:41:44 | |

convicted after the murder of three policemen in 1966. | 0:41:44 | 0:41:49 | |

I think it's extremely cruel to lock someone up forever, but in a slightly different way | 0:41:49 | 0:41:54 | |

from executing them, because it's the gift that keeps on giving, if you see what I mean. | 0:41:54 | 0:41:59 | |

You're in prison maybe for 40 or 50 years. | 0:41:59 | 0:42:02 | |

Harry Roberts, the man who murdered three policemen in Shepherd's Bush, | 0:42:02 | 0:42:06 | |

is still in jail after 44 years. | 0:42:06 | 0:42:08 | |

I happen to believe he should still be there, because he committed three very, very nasty gratuitous murders. | 0:42:08 | 0:42:13 | |

And if you let someone like Harry Roberts out - and there's been talk about doing so - | 0:42:13 | 0:42:18 | |

you are effectively saying to others who might want to kill the police, | 0:42:18 | 0:42:21 | |

"He was away for 44 years, but in the end it's forgive and forget." | 0:42:21 | 0:42:25 | |

Wouldn't it be the mark of a more humane society to execute him? | 0:42:27 | 0:42:32 | |

And if that means dealing, through the state, | 0:42:33 | 0:42:38 | |

in a final way with someone who has committed the most grave crime, | 0:42:38 | 0:42:43 | |

then I don't see that that's a problem. | 0:42:43 | 0:42:46 | |

Well, I counter that by simply pointing out | 0:42:46 | 0:42:50 | |

that as a matter of logic, it's much worse for an individual | 0:42:50 | 0:42:54 | |

to spend the rest of their life in prison than to be executed immediately. | 0:42:54 | 0:43:00 | |

I don't take the view that there is, somewhere down there, a hell | 0:43:00 | 0:43:05 | |

that all bad people are going to be tortured by, | 0:43:05 | 0:43:08 | |

I think, you know, if they are turned off, that's an end on it. | 0:43:08 | 0:43:12 | |

And why give them the benefit of being turned off like that, | 0:43:12 | 0:43:19 | |

when they could be made...punished for the rest of their lives? | 0:43:19 | 0:43:25 | |

I think it's a far worse punishment, life imprisonment, | 0:43:25 | 0:43:28 | |

because they suffer. They suffer! | 0:43:28 | 0:43:31 | |

In 1969, Parliament voted overwhelmingly in favour | 0:43:34 | 0:43:37 | |

of permanently abolishing the death penalty for murder. | 0:43:37 | 0:43:41 | |

Two years later, capital punishment was also removed for arson in a Royal Naval dockyard. | 0:43:43 | 0:43:49 | |

Now hanging only remained for treason and piracy. | 0:43:52 | 0:43:56 | |

Britain's new position was soon followed by other western countries, like France and Spain, | 0:44:02 | 0:44:07 | |

which, through the 1970s, would also stop using the death penalty. | 0:44:07 | 0:44:12 | |

Even the USA, which hadn't executed anyone since 1967, | 0:44:16 | 0:44:21 | |

suspended capital punishment in 1972. | 0:44:21 | 0:44:24 | |

In America, the instrument for the temporary abolition of the death penalty was not Congress, | 0:44:26 | 0:44:32 | |

it was the Supreme Court - the one part of the government of America | 0:44:32 | 0:44:37 | |

which is not susceptible to re-election. | 0:44:37 | 0:44:40 | |

It was that body that actually declared | 0:44:40 | 0:44:44 | |

that at least the process of executions in America was unconstitutional. | 0:44:44 | 0:44:48 | |

The Supreme Court's decision infuriated the majority of Americans. | 0:44:51 | 0:44:56 | |

Private papers of the Chief Justice who was in the dissent | 0:44:57 | 0:45:01 | |

indicate he thought that was the end of the death penalty in America | 0:45:01 | 0:45:04 | |

as did most abolitionists who thought they'd won their permanent victory. | 0:45:04 | 0:45:08 | |

They couldn't have been more wrong. | 0:45:08 | 0:45:10 | |

And the states immediately, responding to overwhelmingly public support for the death penalty, | 0:45:10 | 0:45:14 | |

and outrage at the United States Supreme Court decision, re-enacted death penalty statutes. | 0:45:14 | 0:45:20 | |

In 1976, the Supreme Court was forced to review its decision | 0:45:23 | 0:45:28 | |

in response to widespread public pressure. | 0:45:28 | 0:45:31 | |

Less than two years ago, death cells in prisons throughout America | 0:45:31 | 0:45:35 | |

were emptied when the Supreme Court ruled against capital punishment. | 0:45:35 | 0:45:39 | |

The Court decided it was unconstitutional, | 0:45:39 | 0:45:42 | |

because it was a cruel and unusual form of punishment, in the sense that it was so arbitrary. | 0:45:42 | 0:45:47 | |

Some people would be sentenced to death and others merely to a term of imprisonment for the same offence. | 0:45:47 | 0:45:53 | |

Now, the Court is having to think again, and while it's doing so, | 0:45:53 | 0:45:56 | |

death rows throughout the country are filling up again. | 0:45:56 | 0:45:59 | |

The Supreme Court voted to reinstate capital punishment. | 0:46:02 | 0:46:06 | |

And in 1977, Gary Gilmore became the first person to be executed in the US for ten years. | 0:46:08 | 0:46:16 | |

Gilmore eventually insisted that the State of Utah put him to death. | 0:46:17 | 0:46:22 | |

So he was the first of many volunteers from death row, | 0:46:22 | 0:46:26 | |

basically people who could save their own lives | 0:46:26 | 0:46:30 | |

by continuing to appeal | 0:46:30 | 0:46:32 | |

and to have their cases reviewed and have their cases delayed, he took the opposite path. | 0:46:32 | 0:46:38 | |

He volunteered, the State of Utah put him to death and from that day onwards, the execution pattern began | 0:46:38 | 0:46:44 | |

once again in the USA, very slowly at first. | 0:46:44 | 0:46:47 | |

In 1977, there was only two, and in the 1980s, there were a handful each year, | 0:46:47 | 0:46:52 | |

but by the end of the 1990s, there was almost 100 people being put to death each year. | 0:46:52 | 0:46:58 | |

Gilmore was executed by a firing squad in Utah. | 0:47:01 | 0:47:05 | |

Since then, other US States have chosen to use the gas chamber | 0:47:07 | 0:47:10 | |

or lethal injection to carry out death sentences. | 0:47:10 | 0:47:14 | |

Gilmore's execution hit the headlines in the British Press | 0:47:16 | 0:47:20 | |

and inspired some British lawyers to offer to cross the Atlantic | 0:47:20 | 0:47:24 | |

and help defend those facing the death penalty. | 0:47:24 | 0:47:27 | |

Through the 1980s, British lawyers, like Clive Stafford Smith, | 0:47:30 | 0:47:35 | |

took up cases that challenged America's right to execute. | 0:47:35 | 0:47:39 | |

In a fair world, you are going to win, but the world isn't always a fair... | 0:47:39 | 0:47:42 | |

'I'd become obsessed' | 0:47:42 | 0:47:44 | |

with the death penalty and this was from quite a young age. | 0:47:44 | 0:47:49 | |

I was very young when I was writing something about it, | 0:47:49 | 0:47:52 | |

I was about 16 at school and I thought it was a history paper, | 0:47:52 | 0:47:56 | |

I thought the death penalty was history. | 0:47:56 | 0:47:58 | |

When I discovered that the Americans were still killing each other, I was really shocked. | 0:47:58 | 0:48:03 | |

A death row inmate is scheduled to die in the gas chamber in two weeks... | 0:48:03 | 0:48:08 | |

In 1987, a BBC documentary followed Clive Stafford Smith, | 0:48:08 | 0:48:15 | |

who had volunteered to act as the lawyer for a man on death row in Mississippi. | 0:48:15 | 0:48:21 | |

14 Days In May captured his attempts to stop Edward Earl Johnson being executed. | 0:48:21 | 0:48:27 | |

The funny thing is, I think about a future. | 0:48:27 | 0:48:32 | |

Now that might seem crazy - what future could I possibly have | 0:48:33 | 0:48:37 | |

knowing that I might supposedly be executed in the next two weeks? | 0:48:37 | 0:48:41 | |

Despite evidence suggesting Johnson was innocent, | 0:48:42 | 0:48:45 | |

he was executed in a gas chamber on 20th May 1987. | 0:48:45 | 0:48:51 | |

Ladies and gentlemen, | 0:48:51 | 0:48:54 | |

at 12.06am, Wednesday, May 20th, Edward Earl Johnson was executed | 0:48:54 | 0:48:59 | |

in the lethal gas chamber here at the Mississippi State Penitentiary | 0:48:59 | 0:49:03 | |

in conformance with the sentence | 0:49:03 | 0:49:07 | |

of the Circuit Court of Lee County. | 0:49:07 | 0:49:10 | |

Sitting there, watching him be gassed to death in the gas chamber was just horrific. | 0:49:10 | 0:49:17 | |

In a way, the fact that there were cameras there made it slightly easier, | 0:49:17 | 0:49:22 | |

because you thought this was a movie or something and someone would call "Cut!" and it would all be over, | 0:49:22 | 0:49:28 | |

but I think that's what Edward thought and it made it a little easier for him, perhaps. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:33 | |

When the family asked me why, | 0:49:34 | 0:49:36 | |

all I could say was, "It's a sick world, it's a sick world!" Thank you. | 0:49:36 | 0:49:43 | |

14 Days In May was one of a number of British documentaries | 0:49:46 | 0:49:50 | |

which attacked capital punishment in America. | 0:49:50 | 0:49:54 | |

These films helped shape the ongoing debate in the UK. | 0:49:54 | 0:49:58 | |

When you see documentaries of people on death row in America, which are fantastically common, | 0:50:00 | 0:50:06 | |

you get the feeling that this is contributing to the debate here, | 0:50:06 | 0:50:11 | |

reflecting liberal opinion here, | 0:50:11 | 0:50:13 | |

but probably not actually reflecting | 0:50:13 | 0:50:16 | |

what the majority of the population believe. | 0:50:16 | 0:50:18 | |

I don't think it's changed their minds in any way. | 0:50:18 | 0:50:21 | |

In many ways, as so often with these things, it's the liberal elite speaking to the liberal elite. | 0:50:21 | 0:50:26 | |

While British programme makers used the American experience to highlight the flaws in capital punishment, | 0:50:29 | 0:50:36 | |

in the UK itself, there was rising public demand that Britain, too, should begin executing again. | 0:50:36 | 0:50:43 | |

For the first time since abolition, Britain had a Prime Minister, | 0:50:43 | 0:50:48 | |

Margaret Thatcher, who supported the death penalty, | 0:50:48 | 0:50:52 | |

and MPs were given a free vote on the subject throughout the 1980s. | 0:50:52 | 0:50:58 | |

When I first came into Parliament, | 0:50:58 | 0:50:59 | |

there was still, certainly in the public domain, | 0:50:59 | 0:51:02 | |

quite an active debate going on about the death penalty, | 0:51:02 | 0:51:05 | |

because it was the height of the IRA outrages. | 0:51:05 | 0:51:08 | |

Innocent people were dying in random terror acts and people were saying, | 0:51:08 | 0:51:13 | |

"Even if you don't bring it back for anything else, at least bring it back for terrorism." | 0:51:13 | 0:51:18 | |

So there was still quite a lively debate about whether it should be brought back. | 0:51:18 | 0:51:23 | |

When there was a free vote on the death penalty, I always voted for restoration, | 0:51:26 | 0:51:30 | |

because I do believe there's a very strong moral case | 0:51:30 | 0:51:33 | |

for saying that such a deterrent should be available. | 0:51:33 | 0:51:36 | |

This government will never surrender to the IRA. Never! | 0:51:36 | 0:51:42 | |

Really all of that was really smashed | 0:51:42 | 0:51:45 | |

at the end of the '80s and '90s | 0:51:45 | 0:51:48 | |

when, of course, the government had to confront the fact | 0:51:48 | 0:51:53 | |

that in the cases of the Irish terrorists, | 0:51:53 | 0:51:56 | |

particularly the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four, | 0:51:56 | 0:52:00 | |

that all of these people had been exonerated on the basis that they had not had a fair trial | 0:52:00 | 0:52:07 | |

and that...the evidence was not sufficient to convict. | 0:52:07 | 0:52:13 | |

In 1991, the Birmingham Six and Guildford Four were declared innocent | 0:52:15 | 0:52:20 | |

and released after spending almost two decades in prison. | 0:52:20 | 0:52:24 | |

I've been in prison 15 years for something I didn't do, | 0:52:24 | 0:52:29 | |

for something I didn't know anything about. | 0:52:29 | 0:52:32 | |

Had Britain retained the death penalty then, | 0:52:34 | 0:52:36 | |

they would have almost certainly faced execution. | 0:52:36 | 0:52:40 | |

Whether it's Guildford Four, Birmingham Six, Judith Ward, Tottenham Three and so on, | 0:52:40 | 0:52:47 | |

in many of these cases, | 0:52:47 | 0:52:49 | |

what transpired was that... | 0:52:49 | 0:52:53 | |

there was a...a flawed system. | 0:52:53 | 0:52:57 | |

Now, you can't have a final verdict, like an execution, | 0:52:57 | 0:53:02 | |

where you haven't got an infallible system, which means that | 0:53:02 | 0:53:08 | |

there's a serious risk you are going to, as it were, kill innocent people. | 0:53:08 | 0:53:14 | |

It was cases of miscarriages of justice like these | 0:53:17 | 0:53:20 | |

that persuaded many in government that Britain could never reinstate capital punishment. | 0:53:20 | 0:53:25 | |

In 1994, the last free vote took place in Parliament on reintroducing the death penalty. | 0:53:28 | 0:53:34 | |

It was heavily defeated, with Home Secretary Michael Howard | 0:53:34 | 0:53:38 | |

now voting in favour of retaining abolition. | 0:53:38 | 0:53:42 | |

For a long time, I supported capital punishment, | 0:53:45 | 0:53:48 | |

because I thought it was a deterrent, | 0:53:48 | 0:53:51 | |

and actually I still think it is a deterrent, | 0:53:51 | 0:53:56 | |

but I changed my mind, because of the risk of a mistake. | 0:53:56 | 0:54:01 | |

It was the cases of the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four | 0:54:02 | 0:54:07 | |

that changed my mind on that. | 0:54:07 | 0:54:10 | |

I accepted that you could never completely eliminate the risk of mistake | 0:54:10 | 0:54:15 | |

and since then, I've become adverse as well to the whole idea | 0:54:15 | 0:54:21 | |

of the state deliberately taking someone's life. | 0:54:21 | 0:54:24 | |

But it wasn't until 1998, when the Labour government passed the Crime and Disorder Act, | 0:54:28 | 0:54:33 | |

that the death penalty was completely removed from British Law. | 0:54:33 | 0:54:37 | |

Up until then, executions could still be carried out for treason and piracy. | 0:54:38 | 0:54:43 | |

Later that year, the Court of Appeal quashed the 1953 conviction of Derek Bentley | 0:54:45 | 0:54:52 | |

and he was posthumously pardoned. | 0:54:52 | 0:54:54 | |

By 2010, 139 countries had abolished the death penalty. | 0:54:56 | 0:55:01 | |

We are seeing a greater polarisation in the world. | 0:55:09 | 0:55:14 | |

We are seeing a wide gap between the mental make-up | 0:55:14 | 0:55:21 | |

of those people in the countries that oppose the death penalty | 0:55:21 | 0:55:27 | |

and the people in the countries that see no problem with it. | 0:55:27 | 0:55:34 | |

Surprisingly, the country that has the highest cases of capital punishment per capita is Singapore. | 0:55:35 | 0:55:41 | |

But it is believed the country that executes the most people per year is China. | 0:55:42 | 0:55:48 | |

The trouble with China is that it's still a state secret | 0:55:50 | 0:55:53 | |

and the party will not reveal the number of people sentenced to death and executed. So we have no idea, | 0:55:53 | 0:55:58 | |

really, how many people are put to death there. | 0:55:58 | 0:56:01 | |

But at the UN Human Rights Council, at the end of 2007, | 0:56:01 | 0:56:07 | |

the Chinese delegate made a statement | 0:56:07 | 0:56:13 | |

that China was reducing its use of the death penalty | 0:56:13 | 0:56:18 | |

and was setting plans to do so, with the ultimate aim of abolishing it. | 0:56:18 | 0:56:24 | |

Now, this is a statement really from the state, the state authority, that abolition is a goal. | 0:56:24 | 0:56:30 | |

We haven't heard that from the United States, I'm sorry to say, from a State Department. | 0:56:31 | 0:56:36 | |

But even in America today, the use of capital punishment is a lot less widespread. | 0:56:39 | 0:56:44 | |

It's also true that, amongst the 35 states that have the death penalty, | 0:56:44 | 0:56:47 | |

about a third never use it, | 0:56:47 | 0:56:49 | |

another third impose death sentences but rarely carry them out, | 0:56:49 | 0:56:53 | |

and the death sentences that are carried out | 0:56:53 | 0:56:55 | |

are typically in one region of the nation, that is to say the South. | 0:56:55 | 0:56:59 | |

These days, more than half of the death sentences that are executed occur in Texas. | 0:56:59 | 0:57:05 | |

So, is America a death-penalty nation? Well, in parts. | 0:57:05 | 0:57:09 | |

In 2010, those American states which continue to use the death penalty have been challenged over whether | 0:57:11 | 0:57:18 | |

executing an individual in a painful manner infringes their human rights. | 0:57:18 | 0:57:23 | |

This debate could see the end of the death penalty in America. | 0:57:26 | 0:57:30 | |

But its supporters have gone back to 18th-century ideas of punishment | 0:57:30 | 0:57:35 | |

to defend the right to execute. | 0:57:35 | 0:57:37 | |

To say that it has to be painless is to lose sight of what it is, | 0:57:38 | 0:57:43 | |

which is punishment. | 0:57:43 | 0:57:45 | |

In its etymology, in its very meaning, | 0:57:45 | 0:57:49 | |

the word "punishment" comes from the same root as "pain". | 0:57:49 | 0:57:54 | |

It is, in its essential conception, painful. | 0:57:54 | 0:57:59 | |

If it is not painful, it is not punishment. | 0:57:59 | 0:58:03 | |

When killers intentionally, or with depraved indifference, | 0:58:03 | 0:58:08 | |

inflict intense pain and suffering on their victims, | 0:58:08 | 0:58:13 | |

in my view, they should die a quick but painful death. | 0:58:13 | 0:58:17 | |

Not torture, not drawn out, | 0:58:17 | 0:58:20 | |

but quick and painful. | 0:58:20 | 0:58:22 | |

The debate about capital punishment has raged for over 200 years. | 0:58:24 | 0:58:28 | |

Both sides believe they are in the right. | 0:58:31 | 0:58:35 | |

And if the history of capital punishment has taught us one thing... | 0:58:35 | 0:58:39 | |

..it's that both sides will continue to fight their corner, passionately. | 0:58:41 | 0:58:46 | |

To challenge your views and learn more about the justice system, | 0:58:57 | 0:59:01 | |

go to bbc.co.uk/justice and follow the links to the Open University. | 0:59:01 | 0:59:07 |