Ruling by the Book Illuminations: The Private Lives of Medieval Kings

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Ruling by the Book. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Westminster Abbey has always been where religion meets royalty. | 0:00:06 | 0:00:11 | |

Monarchs have been crowned on this site for nearly 1,000 years. | 0:00:13 | 0:00:18 | |

Through the Royal rituals held here, the medieval world lives on, | 0:00:19 | 0:00:24 | |

just as it does in this breathtaking architecture. | 0:00:24 | 0:00:27 | |

But for me, the abbey's most remarkable treasure | 0:00:27 | 0:00:31 | |

is something most people never get to see. | 0:00:31 | 0:00:35 | |

It's hidden from everyone except the occasional scholar | 0:00:36 | 0:00:40 | |

in the abbey library. | 0:00:40 | 0:00:42 | |

MUSIC: "Zadok The Priest" by Handel | 0:00:42 | 0:00:45 | |

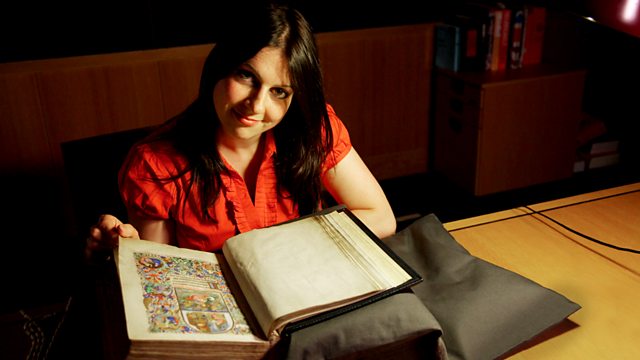

This is Liber Regalis - the Book of the King. | 0:00:50 | 0:00:54 | |

I believe that this part of the regalia | 0:00:55 | 0:00:58 | |

is just as potent a symbol of British monarchy | 0:00:58 | 0:01:01 | |

as the orb, sceptre or crown. | 0:01:01 | 0:01:04 | |

It's been the basis of every coronation | 0:01:05 | 0:01:08 | |

since the reign of Richard II at the end of the 14th century. | 0:01:08 | 0:01:12 | |

Here history, art, and religion collide. | 0:01:13 | 0:01:17 | |

An illuminated manuscript is always much more than a book. | 0:01:20 | 0:01:24 | |

This is a powerful, even mystical object and for us, | 0:01:24 | 0:01:27 | |

it can act as a portal to the lost world of the medieval monarchy. | 0:01:27 | 0:01:32 | |

In this series, I'll be exploring not just the Liber Regalis, | 0:01:35 | 0:01:39 | |

but also the other crown jewels of illumination. | 0:01:39 | 0:01:42 | |

I've been given unrivalled access | 0:01:44 | 0:01:46 | |

to the Royal Manuscript collection at the British Library. | 0:01:46 | 0:01:50 | |

Few people have seen these miraculous survivors, | 0:01:50 | 0:01:54 | |

except the monarchs who owned them. | 0:01:54 | 0:01:57 | |

They were custom made for kings. They were about kings. | 0:01:57 | 0:02:01 | |

And they were read by kings. | 0:02:01 | 0:02:03 | |

I'll be exploring the world which created these manuscripts. | 0:02:06 | 0:02:09 | |

I'll be going to the places where they were made... | 0:02:12 | 0:02:15 | |

..and discovering what they reveal about the centuries of conflict | 0:02:17 | 0:02:20 | |

when England was forged. | 0:02:20 | 0:02:22 | |

It's a story of monarchy | 0:02:26 | 0:02:28 | |

which spans six centuries from the Anglo Saxons to the Tudors. | 0:02:28 | 0:02:31 | |

In this episode, | 0:02:36 | 0:02:38 | |

I'm starting my journey with the first kings to unite England. | 0:02:38 | 0:02:42 | |

I'll reveal how manuscripts gave them divine authority, | 0:02:42 | 0:02:45 | |

even when the reality was rather more human. | 0:02:45 | 0:02:49 | |

Edgar isn't the complete goody-goody that you might think he would be. | 0:02:49 | 0:02:52 | |

If Henry had seen some of the things | 0:02:52 | 0:02:54 | |

Paris was writing, he would be absolutely appalled. | 0:02:54 | 0:02:57 | |

I'll see for myself the unlikely origins of these beautiful objects. | 0:02:57 | 0:03:02 | |

Now, the finest manuscripts came from the urine of the abbot. | 0:03:02 | 0:03:07 | |

And I'll discover | 0:03:09 | 0:03:11 | |

how the ideal of an English monarchy even survived the Norman Conquest. | 0:03:11 | 0:03:16 | |

When the British Library began life in the 18th century, | 0:03:29 | 0:03:33 | |

some of its very first books were donations from the Royal Family. | 0:03:33 | 0:03:37 | |

Among them were some 2,000 illuminated manuscripts, | 0:03:40 | 0:03:44 | |

amassed by the monarchy over several centuries. | 0:03:44 | 0:03:48 | |

The most precious of these are hidden from public view | 0:03:48 | 0:03:52 | |

in a highly secure bunker, deep in the bowels of the building. | 0:03:52 | 0:03:56 | |

Even for an art historian like me, | 0:04:04 | 0:04:07 | |

this inner sanctum is normally off limits. | 0:04:07 | 0:04:10 | |

I've spent my working life poring over individual manuscripts, | 0:04:10 | 0:04:15 | |

but to be allowed in here, in the heart of the British Library, | 0:04:15 | 0:04:20 | |

it's almost overwhelming. | 0:04:20 | 0:04:22 | |

These volumes can give us unique insights | 0:04:24 | 0:04:27 | |

into the monarchs of the past, | 0:04:27 | 0:04:29 | |

from how they ran their courts, | 0:04:29 | 0:04:31 | |

to how they raised their children. | 0:04:31 | 0:04:33 | |

To discover their royal secrets, however, | 0:04:35 | 0:04:37 | |

you often have to dig deeper than the book's professed subject. | 0:04:37 | 0:04:41 | |

Take, for example, this monumental biography of Julius Caesar, | 0:04:44 | 0:04:49 | |

created for Edward IV in 1479. | 0:04:49 | 0:04:51 | |

Gosh. | 0:04:54 | 0:04:56 | |

I'm touching something that, more than 500 years ago, | 0:04:56 | 0:05:00 | |

was made for a king. | 0:05:00 | 0:05:02 | |

As I turn the pages, | 0:05:03 | 0:05:07 | |

I can imagine the hands of Edward IV himself turning them. | 0:05:07 | 0:05:12 | |

The book's subject matter | 0:05:14 | 0:05:16 | |

tells us something about this particular king's interests. | 0:05:16 | 0:05:20 | |

He was one of the greatest generals during the Wars of the Roses, | 0:05:21 | 0:05:25 | |

so would have identified | 0:05:25 | 0:05:26 | |

with its accounts of Caesar's military career. | 0:05:26 | 0:05:29 | |

Edward saw his father and his brother killed in battle | 0:05:30 | 0:05:34 | |

and he saw his grandfather and another brother | 0:05:34 | 0:05:37 | |

executed for treason. | 0:05:37 | 0:05:39 | |

The illustrations here mirror the turmoil | 0:05:42 | 0:05:44 | |

which was often part of a medieval king's life. | 0:05:44 | 0:05:47 | |

Because although this is a book about the ancient world, | 0:05:50 | 0:05:53 | |

it also reflects the era when it was made. | 0:05:53 | 0:05:56 | |

It says here that the manuscript is "fait a Bruges..." | 0:05:57 | 0:06:01 | |

made in Bruges, at the commandment | 0:06:01 | 0:06:05 | |

of the most excellent and victorious prince, the King Edward IV. | 0:06:05 | 0:06:09 | |

So Edward hasn't just bought this, he's commissioned it, | 0:06:11 | 0:06:15 | |

he's ordered it to be made. | 0:06:15 | 0:06:17 | |

It's entirely bespoke, like a Savile Row suit. | 0:06:17 | 0:06:22 | |

He can be certain | 0:06:22 | 0:06:23 | |

that there's not another book like this anywhere in the world. | 0:06:23 | 0:06:27 | |

He would have paid some 3,000 Flemish groats for it - | 0:06:28 | 0:06:31 | |

hundreds of thousands of pounds in today's terms. | 0:06:31 | 0:06:35 | |

It would have taken a scribe six months to handwrite the 359 pages. | 0:06:35 | 0:06:40 | |

And more than one artist was employed | 0:06:41 | 0:06:44 | |

to paint the 40 illustrations here. | 0:06:44 | 0:06:46 | |

These images are not just pleasing to the eye, | 0:06:46 | 0:06:50 | |

they're full of information | 0:06:50 | 0:06:52 | |

and I think they can often speak louder than the words. | 0:06:52 | 0:06:55 | |

Take a look at this one. | 0:06:55 | 0:06:57 | |

It's the first image we encounter in the manuscript. | 0:06:57 | 0:07:00 | |

The subject here is the birth of Caesar, which took place in 100BC. | 0:07:00 | 0:07:05 | |

But the people don't look like ancient Romans, | 0:07:05 | 0:07:08 | |

they're wearing 15th-century costume. | 0:07:08 | 0:07:11 | |

Images like this are hugely useful. We can look at it | 0:07:13 | 0:07:16 | |

and determine what was fashionable during the time of Edward IV. | 0:07:16 | 0:07:22 | |

The dress of the doctor for example. | 0:07:22 | 0:07:24 | |

The sleeves on some of the female attendants, | 0:07:24 | 0:07:27 | |

even these hooks at the front of the headdresses | 0:07:27 | 0:07:30 | |

that were used to keep them balanced, to keep them up. | 0:07:30 | 0:07:33 | |

These are all really important pieces of information | 0:07:33 | 0:07:36 | |

for the historian trying to recreate Edward IV's court. | 0:07:36 | 0:07:40 | |

But for the artist, including some of these contemporary details | 0:07:42 | 0:07:47 | |

allowed them to do something else - | 0:07:47 | 0:07:48 | |

to blur the boundary between the ancient past | 0:07:48 | 0:07:52 | |

and the medieval present. | 0:07:52 | 0:07:53 | |

In the border framing the story, we see Edward's coat of arms | 0:07:55 | 0:08:00 | |

and symbols of the house of York that he belonged to. | 0:08:00 | 0:08:04 | |

Edward was very aware that there were rival claimants to his throne, | 0:08:04 | 0:08:08 | |

so he needed to establish his lineage and his legitimacy. | 0:08:08 | 0:08:12 | |

I think there are elements within this image that do that for him. | 0:08:12 | 0:08:17 | |

Growing out from the crown, | 0:08:18 | 0:08:20 | |

these roses represent a stylised family tree. | 0:08:20 | 0:08:24 | |

If you follow the line upwards, it leads directly to the infant Caesar. | 0:08:25 | 0:08:30 | |

This vertical line dominates the page. | 0:08:33 | 0:08:37 | |

You could say, it's a line of succession. | 0:08:37 | 0:08:41 | |

There's so much here about royal blood. | 0:08:43 | 0:08:46 | |

We even have this bowl of blood here sat on the table. | 0:08:46 | 0:08:50 | |

It's the result of young Julius' Caesarean birth. | 0:08:51 | 0:08:55 | |

The red is sprinkled with gold to show it's imperial blood. | 0:08:55 | 0:08:59 | |

The eye connects this with all the red and gold in Edward's heraldry, | 0:08:59 | 0:09:04 | |

encouraging the mind to connect the two men. | 0:09:04 | 0:09:08 | |

So I think what this image is showing | 0:09:08 | 0:09:10 | |

is that there's a direct link | 0:09:10 | 0:09:13 | |

between one of the greatest emperors of the ancient world | 0:09:13 | 0:09:16 | |

and Edward IV, this medieval King of England. | 0:09:16 | 0:09:21 | |

Edward offers just one example | 0:09:26 | 0:09:28 | |

of how monarchs made use of manuscripts. | 0:09:28 | 0:09:30 | |

Long before HIS reign, | 0:09:32 | 0:09:34 | |

kings were using books to prove their legitimacy, | 0:09:34 | 0:09:37 | |

define their image and assert their power. | 0:09:37 | 0:09:40 | |

The story begins in the courts of Anglo Saxon rulers. | 0:09:44 | 0:09:48 | |

This was an era | 0:09:53 | 0:09:55 | |

when the greatest power in the British Isles was the Church | 0:09:55 | 0:09:58 | |

and when most illuminated manuscripts | 0:09:58 | 0:10:00 | |

were made in monastic settings. | 0:10:00 | 0:10:02 | |

These sacred artefacts radiated divine power | 0:10:06 | 0:10:10 | |

which would prove invaluable to the first kings of England. | 0:10:10 | 0:10:15 | |

This is the earliest English manuscript | 0:10:16 | 0:10:20 | |

in the Royal Collection at the British Library. | 0:10:20 | 0:10:23 | |

We can date this book - from the script | 0:10:23 | 0:10:26 | |

and from the remarkable decoration - | 0:10:26 | 0:10:28 | |

to the first half of the 8th century, | 0:10:28 | 0:10:31 | |

so firmly in the Anglo Saxon period, | 0:10:31 | 0:10:34 | |

this great period of production of manuscripts | 0:10:34 | 0:10:38 | |

and particularly of what we have here - the four Gospels in Latin. | 0:10:38 | 0:10:42 | |

I can see you're handling it without gloves. | 0:10:42 | 0:10:45 | |

-Now that's official British Library policy, isn't it? -It is. | 0:10:45 | 0:10:48 | |

You see, as I turn the pages, I have a very good sense, feedback, | 0:10:48 | 0:10:53 | |

from the end of my fingers as to how hard to press on the pages, | 0:10:53 | 0:10:58 | |

what speed to do it at. It gives me much greater sense of control. | 0:10:58 | 0:11:04 | |

The book is very important to the Christian religion, isn't it? | 0:11:04 | 0:11:07 | |

Yes. | 0:11:07 | 0:11:09 | |

The early Christian church is a sort of powerhouse for creating books. | 0:11:09 | 0:11:13 | |

Every church, every religious house | 0:11:13 | 0:11:16 | |

would have had at least a copy of the Gospels | 0:11:16 | 0:11:19 | |

and other parts of the Bible. | 0:11:19 | 0:11:22 | |

But a book like this would rarely ever been seen | 0:11:22 | 0:11:27 | |

by the average person during this period. | 0:11:27 | 0:11:30 | |

And if they saw it at all, | 0:11:30 | 0:11:32 | |

they would make nothing of the script because they couldn't read. | 0:11:32 | 0:11:36 | |

What's the Royal connection with this manuscript? | 0:11:36 | 0:11:39 | |

Well, the Royal connection comes, if I turn another page here, | 0:11:39 | 0:11:43 | |

we continue the biblical text, so this is Matthew's Gospel, | 0:11:43 | 0:11:47 | |

but we also have, at the foot of the left hand column, | 0:11:47 | 0:11:50 | |

this inscription which relates to King Athelstan | 0:11:50 | 0:11:53 | |

who was crowned in 925. | 0:11:53 | 0:11:57 | |

And the inscription says, | 0:11:57 | 0:11:59 | |

"Athelstan the King freed Eadhelm forthwith | 0:11:59 | 0:12:05 | |

"as he was crowned King." | 0:12:05 | 0:12:10 | |

So it seems to be that this was an important statement | 0:12:10 | 0:12:14 | |

that he was doing this, if you like, | 0:12:14 | 0:12:16 | |

an act of kingly generosity right from the start of his reign. | 0:12:16 | 0:12:21 | |

And that's captured, it's recorded in a Biblical manuscript. | 0:12:21 | 0:12:25 | |

This is interesting, isn't it? | 0:12:25 | 0:12:27 | |

We've got this reference to kingship | 0:12:27 | 0:12:29 | |

in what's otherwise a functional Gospel book, isn't it? | 0:12:29 | 0:12:34 | |

It is. The context gives authority, links the two together. | 0:12:34 | 0:12:40 | |

And it's recorded for all time now. | 0:12:40 | 0:12:42 | |

The appearance of a king's name and deeds | 0:12:48 | 0:12:51 | |

in something as valued as a Gospel book is evidence of his power. | 0:12:51 | 0:12:55 | |

And Athelstan is a king who deserves to be remembered. | 0:12:57 | 0:13:01 | |

He changed the course of this island's history. | 0:13:01 | 0:13:04 | |

In the centuries before Athelstan's reign, | 0:13:05 | 0:13:08 | |

there had been a number of different Anglo Saxon kingdoms. | 0:13:08 | 0:13:12 | |

Through a mixture of diplomacy and war, | 0:13:12 | 0:13:14 | |

Athelstan united them all into a single entity. | 0:13:14 | 0:13:18 | |

The place he treated as capital of his new kingdom was near its centre. | 0:13:22 | 0:13:26 | |

Malmesbury. | 0:13:26 | 0:13:27 | |

These days there's little to suggest | 0:13:34 | 0:13:36 | |

that the Cotswolds town was once such a significant place. | 0:13:36 | 0:13:41 | |

But there's one big clue to its past glory - | 0:13:43 | 0:13:48 | |

its vast, half-ruined abbey. | 0:13:48 | 0:13:51 | |

This site has been used for Christian worship since 676. | 0:13:55 | 0:14:00 | |

As well as being a mighty warrior, | 0:14:08 | 0:14:10 | |

Athelstan was famously pious and he was a generous patron of this abbey. | 0:14:10 | 0:14:16 | |

It's also where he was buried in 939AD, | 0:14:20 | 0:14:24 | |

though the statue on his tomb is more recent, from the 15th century. | 0:14:24 | 0:14:28 | |

Amazingly though, there is an image that survives from his own lifetime. | 0:14:30 | 0:14:34 | |

And apart from the faces on coins, | 0:14:34 | 0:14:36 | |

it's the earliest surviving portrait of an English king. | 0:14:36 | 0:14:41 | |

He's pictured showing his devotion | 0:14:43 | 0:14:46 | |

to the great Northumbrian saint Cuthbert. | 0:14:46 | 0:14:49 | |

This image is found at the front of a religious manuscript | 0:14:49 | 0:14:53 | |

which Athelstan gave to a northern monastery. | 0:14:53 | 0:14:56 | |

I get goosebumps when I look at this image. | 0:14:58 | 0:15:01 | |

I'm actually looking at the face of King Athelstan. | 0:15:01 | 0:15:04 | |

And he's holding a book. | 0:15:04 | 0:15:07 | |

So here we have a book within a book. It's setting up this idea | 0:15:07 | 0:15:11 | |

that there's a close association between kings and manuscripts. | 0:15:11 | 0:15:16 | |

Whether he's depicted with them, donating them, | 0:15:18 | 0:15:21 | |

or having deeds recorded in them, | 0:15:21 | 0:15:23 | |

it seems the first King of all England needs manuscripts. | 0:15:23 | 0:15:28 | |

Back in the library, | 0:15:30 | 0:15:31 | |

another survivor from Athelstan's reign gives us more insights. | 0:15:31 | 0:15:36 | |

This Gospel book is again over 1,000 years old, | 0:15:38 | 0:15:41 | |

though its pages have been remounted more recently. | 0:15:41 | 0:15:46 | |

It was damaged by fire in 1731 - | 0:15:46 | 0:15:49 | |

you can see how it's all singed around the edges. | 0:15:49 | 0:15:53 | |

It acts as a reminder of how vulnerable these things are | 0:15:53 | 0:15:57 | |

and how lucky we are that any manuscripts survive at all. | 0:15:57 | 0:16:00 | |

Yet what's MOST striking is not the damage, | 0:16:01 | 0:16:04 | |

but how vivid and impressive this work of art still is. | 0:16:04 | 0:16:08 | |

Despite everything this manuscript's been through | 0:16:15 | 0:16:18 | |

and the passage of centuries, | 0:16:18 | 0:16:20 | |

the gold still really shines out of the page. | 0:16:20 | 0:16:24 | |

Literally illuminates. | 0:16:26 | 0:16:28 | |

And I suppose that's the advantage | 0:16:28 | 0:16:30 | |

of the pages being kept out of the light | 0:16:30 | 0:16:33 | |

and shut within covers all this time. | 0:16:33 | 0:16:35 | |

And here's the name of Athelstan. | 0:16:40 | 0:16:43 | |

It says he's "Anglorum basyleos", | 0:16:43 | 0:16:45 | |

ruler of the English and ruler of all of Britain. | 0:16:45 | 0:16:50 | |

This is a reminder of why he's so important. | 0:16:50 | 0:16:53 | |

But what reveals most about Athelstan is not the words here, | 0:16:56 | 0:16:59 | |

but the pictures. | 0:16:59 | 0:17:01 | |

The human figures are relatively realistic. | 0:17:02 | 0:17:06 | |

There's even some basic use of perspective. | 0:17:06 | 0:17:10 | |

At the time, English artists didn't work in this style, | 0:17:10 | 0:17:13 | |

which means this book must have come from the European mainland, | 0:17:13 | 0:17:16 | |

most likely the Low Countries. | 0:17:16 | 0:17:20 | |

I find the presence of this great Continental artwork | 0:17:20 | 0:17:23 | |

in English Royal hands a really inspiring thought. | 0:17:23 | 0:17:27 | |

It shows that the British Isles weren't some backwater, | 0:17:27 | 0:17:30 | |

disconnected from the rest of Europe. | 0:17:30 | 0:17:33 | |

Athelstan's court was welcoming | 0:17:33 | 0:17:35 | |

international scholars and artists with open arms. | 0:17:35 | 0:17:38 | |

The King's reach clearly extended | 0:17:39 | 0:17:41 | |

beyond the borders of the new England. | 0:17:41 | 0:17:43 | |

On another page, there's evidence of his foreign policy. | 0:17:45 | 0:17:49 | |

Here's another inscription - | 0:17:50 | 0:17:52 | |

"Odda Rex". Definitely not the name of an English king. | 0:17:52 | 0:17:56 | |

He is what would now be known as a German, Otto I. | 0:17:56 | 0:18:00 | |

Athelstan had many sisters and half-sisters, | 0:18:02 | 0:18:05 | |

and he used them as diplomatic tools, | 0:18:05 | 0:18:07 | |

marrying them into the different royal families across Europe. | 0:18:07 | 0:18:11 | |

Apparently he sent two to Otto so he could have a choice, | 0:18:11 | 0:18:14 | |

and he, of course, chose the most beautiful of the sisters. | 0:18:14 | 0:18:17 | |

What Athelstan got in return was international prestige and influence | 0:18:19 | 0:18:23 | |

and, most likely, he also got this manuscript as a wedding gift. | 0:18:23 | 0:18:28 | |

It's proof that there was more value to a manuscript | 0:18:30 | 0:18:33 | |

than just its contents. It could also act as a kind of currency. | 0:18:33 | 0:18:37 | |

Some time after Otto gave him this manuscript, | 0:18:38 | 0:18:42 | |

Athelstan passes it on to the monks of Christ Church in Canterbury. | 0:18:42 | 0:18:46 | |

He's spreading Christian learning throughout the country. | 0:18:46 | 0:18:50 | |

In return, the grateful monks add a poem to the Gospel book | 0:18:52 | 0:18:56 | |

which praises devout King Athelstan, renowned through the wide world. | 0:18:56 | 0:19:01 | |

Manuscripts clearly enhanced Athelstan's status. | 0:19:10 | 0:19:14 | |

And a strong reputation | 0:19:16 | 0:19:18 | |

gave him more power over his newly-formed kingdom. | 0:19:18 | 0:19:22 | |

Greater territory brings a lot of responsibilities. | 0:19:22 | 0:19:25 | |

Hand-in-hand with that, we see Athelstan using a more judicial, | 0:19:25 | 0:19:30 | |

bureaucratic type of kingship because he's got more to administer. | 0:19:30 | 0:19:34 | |

And we see him setting up an obligatory assembly | 0:19:34 | 0:19:37 | |

and every noble from across the entire country | 0:19:37 | 0:19:41 | |

has got to attend his court regularly. | 0:19:41 | 0:19:43 | |

We see him trying to run the economy effectively by controlling coinage, | 0:19:43 | 0:19:48 | |

so it really is a concerted effort | 0:19:48 | 0:19:51 | |

to make England function as a country as a whole. | 0:19:51 | 0:19:54 | |

Yes, that's definitely the impression I get | 0:19:54 | 0:19:57 | |

from looking at Athelstan and the manuscripts surrounding him. | 0:19:57 | 0:20:00 | |

He's harnessing all the language and the imagery of power. | 0:20:00 | 0:20:03 | |

If you're concerned for your image, | 0:20:03 | 0:20:06 | |

if you're concerned for the sort of reputation of your kingship, | 0:20:06 | 0:20:10 | |

as Athelstan was, you have a scribe to talk up your kingship, | 0:20:10 | 0:20:14 | |

to try to elevate and create a sense of a king | 0:20:14 | 0:20:18 | |

who's more than the sort of king you used to have in England. | 0:20:18 | 0:20:21 | |

-It's an amazing propaganda machine, isn't it? -It is a propaganda... | 0:20:21 | 0:20:24 | |

You've got everything working together - | 0:20:24 | 0:20:27 | |

law, imagery, language all building him up. | 0:20:27 | 0:20:30 | |

One could argue it's no accident that we have the first image of a king | 0:20:30 | 0:20:35 | |

being the image of Athelstan | 0:20:35 | 0:20:37 | |

when he was a king who was so concerned for his image | 0:20:37 | 0:20:40 | |

and had to be because he was pushing forward the frontiers of kingship. | 0:20:40 | 0:20:44 | |

When Athelstan died in 939AD, | 0:20:49 | 0:20:53 | |

he left not just a united England, | 0:20:53 | 0:20:56 | |

but a model for how manuscripts could enhance royal image. | 0:20:56 | 0:21:00 | |

His successors would build on that legacy. | 0:21:02 | 0:21:05 | |

Just 20 years later, when Edgar the Peaceful takes the throne, | 0:21:10 | 0:21:14 | |

the role of King of England had evolved further. | 0:21:14 | 0:21:18 | |

Like his Great Uncle Athelstan, | 0:21:21 | 0:21:23 | |

Edgar lives on in manuscripts held by the British Library. | 0:21:23 | 0:21:27 | |

One is a Royal charter, | 0:21:30 | 0:21:33 | |

which shows clearly just how powerful a figure Edgar was, | 0:21:33 | 0:21:36 | |

and where he got his power from - the Church. | 0:21:36 | 0:21:40 | |

Gosh. | 0:21:43 | 0:21:44 | |

Wow. Well, we're clearly dealing | 0:21:47 | 0:21:49 | |

with something quite different to what we've seen before. | 0:21:49 | 0:21:53 | |

Every page is written in gold. | 0:21:53 | 0:21:57 | |

It just glistens off the vellum there. | 0:21:57 | 0:22:01 | |

You can only imagine what it must have been worth. | 0:22:01 | 0:22:06 | |

It shows me that this text | 0:22:06 | 0:22:08 | |

is about something, and someone, very important. | 0:22:08 | 0:22:12 | |

It was created by the monks of Winchester's New Minster. | 0:22:13 | 0:22:17 | |

At the front, they included a flattering portrait of Edgar. | 0:22:17 | 0:22:20 | |

And what have we here? | 0:22:22 | 0:22:24 | |

Another book, | 0:22:24 | 0:22:26 | |

held in the hand of the King, a gold book, probably this book itself. | 0:22:26 | 0:22:31 | |

And again we have this connection | 0:22:31 | 0:22:34 | |

between an English monarch and manuscripts, | 0:22:34 | 0:22:37 | |

the giving of manuscripts. | 0:22:37 | 0:22:39 | |

The book is doing the same job as the crown in this image. | 0:22:41 | 0:22:45 | |

It too is now a symbol of royal power. | 0:22:45 | 0:22:48 | |

This charter was created to commemorate | 0:22:48 | 0:22:52 | |

a major reform of England's monasteries in 964 | 0:22:52 | 0:22:55 | |

in which Edgar gave more power and land to the Benedictine order. | 0:22:55 | 0:22:59 | |

In return, the artist of the charter | 0:23:02 | 0:23:04 | |

seems to have elevated the King to a near-divine status. | 0:23:04 | 0:23:08 | |

There's some potent symbolism going on here. | 0:23:09 | 0:23:12 | |

This is the first time | 0:23:12 | 0:23:14 | |

we've seen an English king inserted so prominently in a spiritual scene. | 0:23:14 | 0:23:18 | |

He's there in the centre | 0:23:18 | 0:23:22 | |

and, in terms of scale, he seems to be the largest figure. | 0:23:22 | 0:23:26 | |

And then coming after that very regal frontispiece, | 0:23:27 | 0:23:31 | |

we see the name of the king himself, "Edgar Rex". King Edgar. | 0:23:31 | 0:23:36 | |

And it's on the facing page to this Kairo, | 0:23:36 | 0:23:40 | |

the name of the King of Kings Christ. | 0:23:40 | 0:23:43 | |

So Edgar and Christ paired up alongside one another. | 0:23:43 | 0:23:47 | |

His image is one of pious perfection. | 0:23:51 | 0:23:54 | |

The reality was rather different. | 0:23:56 | 0:23:58 | |

Edgar made his capital in Winchester. | 0:24:07 | 0:24:11 | |

The city was also one of the centres of the English Church | 0:24:13 | 0:24:17 | |

in the 10th century. | 0:24:17 | 0:24:19 | |

Near where the cathedral now stands, | 0:24:27 | 0:24:29 | |

the scribes at the New Minster produced Edgar's golden charter, | 0:24:29 | 0:24:33 | |

along with many other great illuminated manuscripts of the era. | 0:24:33 | 0:24:38 | |

In this city, the relationship between church and state | 0:24:41 | 0:24:45 | |

could not have been closer. | 0:24:45 | 0:24:48 | |

Well, there'd be an amazing collection of buildings here. | 0:24:48 | 0:24:52 | |

We're actually walking over the Old Minster | 0:24:52 | 0:24:54 | |

which was the Anglo Saxon cathedral. | 0:24:54 | 0:24:57 | |

Over there is the New Minster of the charter, | 0:24:57 | 0:25:01 | |

the Royal Nunnery back there and, ahead of us, the Royal Palace. | 0:25:01 | 0:25:04 | |

-Winchester's an important place, isn't it? -It is. | 0:25:04 | 0:25:08 | |

London might be a trading centre but this is really the ritual | 0:25:08 | 0:25:13 | |

and the religious centre of Edgar's England. | 0:25:13 | 0:25:16 | |

We know from the New Minster charter that Edgar's very involved | 0:25:16 | 0:25:20 | |

with church affairs here in Winchester. Why might that be? | 0:25:20 | 0:25:23 | |

Bishop Aethelwold of Winchester was actually Edgar's tutor, | 0:25:23 | 0:25:27 | |

so he's been indoctrinated from a young age | 0:25:27 | 0:25:30 | |

about his duty towards the Church. | 0:25:30 | 0:25:33 | |

But Edgar isn't the goody-goody that you might think he would be. | 0:25:33 | 0:25:36 | |

He has got a reputation as a womaniser. | 0:25:36 | 0:25:39 | |

Yes, and it's all sorts of women, isn't it, including nuns | 0:25:39 | 0:25:43 | |

and chasing them into sewers and things. | 0:25:43 | 0:25:45 | |

Yes, it's not the sort of relationship with nuns | 0:25:45 | 0:25:48 | |

that Aethelwold was anticipating! | 0:25:48 | 0:25:50 | |

But later stories do associate him with attempts to seduce a nun. | 0:25:52 | 0:25:55 | |

-Uh-huh! -Though, admittedly, he wanted to marry her, | 0:25:55 | 0:25:58 | |

but when she turned him down and ran away from him, | 0:25:58 | 0:26:02 | |

he did agree to marry her cousin instead. | 0:26:02 | 0:26:04 | |

So we could look at the frontispiece as propaganda for the King's image? | 0:26:04 | 0:26:08 | |

Yes, that is the public view that you're being given of Edgar. | 0:26:08 | 0:26:11 | |

He is Christ's representative on Earth | 0:26:11 | 0:26:14 | |

and a figure that is bolstered by these religious connections. | 0:26:14 | 0:26:18 | |

In return for cleaning up his image, | 0:26:21 | 0:26:24 | |

the King gave the church large donations of money and land. | 0:26:24 | 0:26:28 | |

This mutual back-scratching is suggested by an image of Edgar | 0:26:30 | 0:26:35 | |

where he's literally bound together with his clergy | 0:26:35 | 0:26:38 | |

by another Winchester manuscript. | 0:26:38 | 0:26:41 | |

The boundaries between divine authority and earthly power | 0:26:41 | 0:26:45 | |

are increasingly blurred. | 0:26:45 | 0:26:47 | |

It was very much in all their interests to work together. | 0:26:48 | 0:26:52 | |

The kings protect the monasteries, the monasteries protect the king | 0:26:52 | 0:26:56 | |

but also, of course, promote his image. | 0:26:56 | 0:26:58 | |

Yes, that's strong here, isn't it? | 0:26:58 | 0:27:00 | |

Yes, very much you see here, with the King wearing that imperial crown. | 0:27:00 | 0:27:05 | |

And, of course, there is this parallel | 0:27:05 | 0:27:08 | |

between the King on Earth and Christ in heaven. | 0:27:08 | 0:27:12 | |

It's a really big statement about just how important the King is | 0:27:12 | 0:27:16 | |

and how different he is from other laymen | 0:27:16 | 0:27:19 | |

or indeed other rulers in other parts of Britain. | 0:27:19 | 0:27:21 | |

So in texts like this and the New Minster charter, | 0:27:21 | 0:27:24 | |

Edgar's taking a new position, isn't he? | 0:27:24 | 0:27:26 | |

He's referring to himself as the Vicar of Christ. | 0:27:26 | 0:27:29 | |

This is quite an unusual change in the idea of kingship, isn't it? | 0:27:29 | 0:27:32 | |

Yeah, I think there's a much more self-conscious use | 0:27:32 | 0:27:35 | |

of the religious role of kings. The Church is really trying to show here | 0:27:35 | 0:27:40 | |

that kingship is almost a sort of clerical office. | 0:27:40 | 0:27:44 | |

They're moving it away from the, you know, the king as a war leader. | 0:27:44 | 0:27:51 | |

Although the imagery of monarchy was becoming more defined, | 0:27:55 | 0:27:59 | |

no king at this time was entirely secure in his position. | 0:27:59 | 0:28:05 | |

The threat from challengers to the throne | 0:28:05 | 0:28:07 | |

and enemies to the kingdom was constant. | 0:28:07 | 0:28:10 | |

Just 40 years later, a Dane was ruling England. | 0:28:15 | 0:28:20 | |

Yet unlike other invaders, | 0:28:20 | 0:28:22 | |

Cnut is not remembered now as a violent conqueror. | 0:28:22 | 0:28:25 | |

Quite how he managed to integrate himself into English history | 0:28:27 | 0:28:32 | |

is partly explained in the pages of another book | 0:28:32 | 0:28:35 | |

produced at Winchester's New Minster. | 0:28:35 | 0:28:38 | |

This is a list of Anglo Saxon names | 0:28:39 | 0:28:42 | |

that's clearly been added to throughout the centuries. | 0:28:42 | 0:28:46 | |

We've got Leofric, | 0:28:46 | 0:28:48 | |

Alfric...and down here Godwin. | 0:28:48 | 0:28:51 | |

At its simplest, | 0:28:52 | 0:28:54 | |

this is a membership register | 0:28:54 | 0:28:56 | |

of people associated with the brotherhood at the New Minster. | 0:28:56 | 0:29:00 | |

But it's also a list of names that are going to be prayed for. | 0:29:00 | 0:29:04 | |

If your name was written into these pages, | 0:29:05 | 0:29:08 | |

it was believed you'd go to the front of the queue for heaven. | 0:29:08 | 0:29:12 | |

Because this is no ordinary manuscript. | 0:29:12 | 0:29:15 | |

It's the Liber Vitae, the Book of Life. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:18 | |

It's the earthly draft | 0:29:20 | 0:29:21 | |

of the register Christ will call from on the Day of Judgement. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:25 | |

It shows where those in the Church's good books | 0:29:26 | 0:29:29 | |

can hope to spend eternity. | 0:29:29 | 0:29:31 | |

And underneath is where you'd end up if your name's not on the list. | 0:29:32 | 0:29:36 | |

Given pride of place in this sacred artefact of the English church, | 0:29:46 | 0:29:50 | |

however, is a foreigner. Cnut. | 0:29:50 | 0:29:53 | |

These days Cnut's best known | 0:29:54 | 0:29:56 | |

for that story about turning back the waves. | 0:29:56 | 0:29:58 | |

But the makers of this image | 0:29:58 | 0:30:00 | |

knew him more as a fearsome Danish warrior | 0:30:00 | 0:30:02 | |

who'd conquered their country through a series of bloody battles. | 0:30:02 | 0:30:05 | |

Even in this scene of pious harmony, he's still drawing his sword. | 0:30:09 | 0:30:14 | |

But keeping hold of the throne would call for more than military power. | 0:30:14 | 0:30:18 | |

What Cnut really needs to do to maintain power | 0:30:19 | 0:30:22 | |

is to establish his legitimacy. | 0:30:22 | 0:30:24 | |

And looking at this image, | 0:30:24 | 0:30:26 | |

I can see a number of ways in which he's trying to do that. | 0:30:26 | 0:30:29 | |

He's got this crown coming down from heaven to begin with. | 0:30:29 | 0:30:32 | |

But he's also got this other figure pictured alongside him. | 0:30:32 | 0:30:35 | |

And the inscription reads, "Aelfgifu Regina" - Queen Aelfgifu. | 0:30:35 | 0:30:41 | |

Aelfgifu was married to Ethelred the Unready, | 0:30:41 | 0:30:44 | |

one of Cnut's Anglo-Saxon predecessors. | 0:30:44 | 0:30:46 | |

By marrying her, he's bringing the two nations together, | 0:30:46 | 0:30:50 | |

and this image is really emphasising that. | 0:30:50 | 0:30:52 | |

she's put in this position of prominence | 0:30:52 | 0:30:55 | |

on the right hand of the father, beneath the feet of the virgin. | 0:30:55 | 0:31:00 | |

This is a hugely significant image for me. | 0:31:00 | 0:31:03 | |

Other than religious figures, | 0:31:03 | 0:31:05 | |

there are virtually no women in manuscripts of this period. | 0:31:05 | 0:31:08 | |

It's also proof of just how badly | 0:31:10 | 0:31:12 | |

Cnut needed some Anglo-Saxon pedigree. | 0:31:12 | 0:31:16 | |

The other figures almost literally supporting his kingship here | 0:31:16 | 0:31:19 | |

are the monks of the New Minster. | 0:31:19 | 0:31:22 | |

In order to keep a grip on his throne, | 0:31:22 | 0:31:24 | |

Cnut needed the support and the political backing of the Church. | 0:31:24 | 0:31:28 | |

So he tries to ingratiate himself with particular establishments, | 0:31:28 | 0:31:32 | |

like New Minster in Winchester. And how does he do that? | 0:31:32 | 0:31:36 | |

He gives donations and gifts. | 0:31:36 | 0:31:38 | |

Here we see a magnificent golden cross | 0:31:38 | 0:31:41 | |

that he's placing on the altar. | 0:31:41 | 0:31:43 | |

Crucifix and manuscript would have been displayed side by side. | 0:31:45 | 0:31:49 | |

In today's cathedral, there's a similar arrangement. | 0:31:49 | 0:31:54 | |

People looking at this image | 0:31:56 | 0:31:58 | |

will see the same gold cross on the altar. | 0:31:58 | 0:32:01 | |

Like a picture by Escher, it's an endlessly repeating image, | 0:32:01 | 0:32:06 | |

where the real and the imagined are blended. | 0:32:06 | 0:32:08 | |

And there's a further dimension at work here. | 0:32:12 | 0:32:15 | |

The cross is pictured on the Day of Judgement, | 0:32:15 | 0:32:18 | |

which means it also exists at the end of time. | 0:32:18 | 0:32:22 | |

The medieval imagination had little difficulty | 0:32:23 | 0:32:26 | |

moving between the now and the eternal. | 0:32:26 | 0:32:29 | |

And so this cross in the manuscript | 0:32:29 | 0:32:31 | |

is acting like a portal between earth and heaven. | 0:32:31 | 0:32:35 | |

The other book on the altar in Cnut's day | 0:32:43 | 0:32:46 | |

would have been King Edgar's charter. | 0:32:46 | 0:32:48 | |

The two images side by side would have further reinforced | 0:32:48 | 0:32:52 | |

the idea that Cnut was Edgar's rightful successor. | 0:32:52 | 0:32:55 | |

All Cnut's efforts to write himself into England's Royal story | 0:33:00 | 0:33:03 | |

eventually paid off. He remains to this day at Winchester, | 0:33:03 | 0:33:08 | |

in one of the cathedral's ancient mortuary chests. | 0:33:08 | 0:33:11 | |

He clearly made the grade in the eyes of the Church. | 0:33:12 | 0:33:16 | |

The image of kingship that Cnut was to create | 0:33:16 | 0:33:19 | |

has withstood the tides of time for almost a thousand years. | 0:33:19 | 0:33:23 | |

The manuscript was such a powerful object a thousand years ago, | 0:33:32 | 0:33:35 | |

it seemed almost alive. | 0:33:35 | 0:33:37 | |

It's a quality referred to in a poem of the period. | 0:33:37 | 0:33:40 | |

So I've got an Anglo-Saxon riddle for you. | 0:33:40 | 0:33:44 | |

SHE SPEAKS IN OLD ENGLISH | 0:33:44 | 0:33:46 | |

Have you guessed what it is yet? No? | 0:33:53 | 0:33:56 | |

The answer to the riddle and the voice we hear in the poem is vellum. | 0:34:04 | 0:34:10 | |

Paper doesn't reach northern Europe until the 14th century. | 0:34:10 | 0:34:14 | |

All manuscripts created here before then are written on | 0:34:14 | 0:34:17 | |

the treated skins of calves and other beasts. | 0:34:17 | 0:34:21 | |

The Anglo-Saxons would have been very aware | 0:34:21 | 0:34:24 | |

that their precious manuscripts | 0:34:24 | 0:34:26 | |

had their origins in the living creatures around them. | 0:34:26 | 0:34:30 | |

Amazingly, vellum is still being made today, | 0:34:35 | 0:34:38 | |

in much the same way as the Anglo-Saxon poet describes. | 0:34:38 | 0:34:42 | |

William Cowley in Buckinghamshire are one of just a handful of firms | 0:34:43 | 0:34:47 | |

in the world keeping the tradition alive. | 0:34:47 | 0:34:51 | |

-So here we are, this is our storeroom. -Wow. | 0:34:55 | 0:34:58 | |

The raw material, as we say. | 0:34:58 | 0:35:01 | |

-Animal skins. -Animal skins. | 0:35:01 | 0:35:02 | |

-Nice and smelly. -Lots and lots of animal skins. | 0:35:02 | 0:35:04 | |

It does smell, yeah. Oh! | 0:35:04 | 0:35:06 | |

So we have calf here, we have goat over there, | 0:35:06 | 0:35:09 | |

-and in the box there would be sheep. -Wow. | 0:35:09 | 0:35:11 | |

Every skin in here | 0:35:11 | 0:35:12 | |

-has been hand-selected from the abattoir. -What do you look for? | 0:35:12 | 0:35:15 | |

We'll be looking for if there's any marks from barbed wire, | 0:35:15 | 0:35:19 | |

from thorns, even insects. | 0:35:19 | 0:35:21 | |

A tick will get well into the skin | 0:35:21 | 0:35:23 | |

-and can leave quite a hole. -Oh, I've seen manuscripts | 0:35:23 | 0:35:26 | |

with these large holes which have been written around. | 0:35:26 | 0:35:29 | |

If you pick the wrong skins, you'll end up with a duff manuscript. | 0:35:29 | 0:35:33 | |

Right, so what happens next, then? | 0:35:33 | 0:35:34 | |

-Well, from here, we'll take the skins... -Right. | 0:35:34 | 0:35:37 | |

-..and we then have to soak them. -OK. | 0:35:37 | 0:35:41 | |

Ooh, it smells like rotting flesh. | 0:35:41 | 0:35:43 | |

Well, yeah, you're not that far away. | 0:35:43 | 0:35:45 | |

What we've done is we've now got it soaking in a lime bath. | 0:35:45 | 0:35:48 | |

-OK. -Now, bear in mind, if you go back far enough, | 0:35:48 | 0:35:52 | |

-it was urine and dog faeces, and everything. -Ugh, yeah. | 0:35:52 | 0:35:55 | |

Cos what you're looking to do, | 0:35:55 | 0:35:57 | |

you're looking to get the skin to start to break down. | 0:35:57 | 0:36:00 | |

The finest manuscripts came from the urine of the Abbot. | 0:36:00 | 0:36:05 | |

The Abbot's diet was so much better | 0:36:05 | 0:36:06 | |

-than that of an average monk... -Ah, there you go. | 0:36:06 | 0:36:09 | |

..so his urine was said to be of better quality | 0:36:09 | 0:36:11 | |

when producing parchment and vellum. | 0:36:11 | 0:36:13 | |

So there's all these different things you can adapt | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

-to get the absolute best quality. -Yeah. | 0:36:16 | 0:36:18 | |

-You haven't got Abbot's wee today? -No, no. | 0:36:18 | 0:36:21 | |

-So here we have what we call the grain with the hair on it. -Yeah. | 0:36:26 | 0:36:29 | |

We're looking to get this off... | 0:36:29 | 0:36:31 | |

-Right, right, right. -..without marking the writing surface. -Ah. | 0:36:31 | 0:36:35 | |

This is going to be the writing surface. | 0:36:35 | 0:36:38 | |

And if you feel, you can already feel how soft that is. | 0:36:38 | 0:36:41 | |

Wow, yeah. | 0:36:41 | 0:36:42 | |

'I've handled plenty of vellum over the years, | 0:36:44 | 0:36:47 | |

'but never at this stage of its life.' | 0:36:47 | 0:36:49 | |

-A real parchment maker's apron. -Wow. | 0:36:49 | 0:36:52 | |

Right, so here we go. | 0:36:52 | 0:36:54 | |

-Here's our knife. -Mmm-hmm. | 0:36:54 | 0:36:56 | |

-Just lean over, two hands on the knife... -Yep. | 0:36:56 | 0:37:00 | |

-..and just push down. There you go. -Oh, wow, it's actually... | 0:37:00 | 0:37:03 | |

-Yeah, I'm hardly putting much pressure on there. -No. | 0:37:03 | 0:37:06 | |

Gosh, this process is just like the one that I've read about. | 0:37:06 | 0:37:10 | |

There's an Old English riddle that describes | 0:37:10 | 0:37:13 | |

the process of making a manuscript and it says... | 0:37:13 | 0:37:16 | |

SHE SPEAKS IN OLD ENGLISH | 0:37:16 | 0:37:18 | |

And it's talking about precisely this bit. | 0:37:25 | 0:37:27 | |

-Yes. -Scraping, shaping the skin. -Yep. | 0:37:27 | 0:37:31 | |

And it's so evocative, I really feel like that poem's coming to life | 0:37:31 | 0:37:35 | |

while I'm doing this. | 0:37:35 | 0:37:37 | |

Manufacturing vellum is both labour and time-intensive. | 0:37:42 | 0:37:46 | |

After the fat is scraped off, the skin takes several weeks to dry. | 0:37:46 | 0:37:50 | |

From abattoir to finished sheet can take up to three months - | 0:37:53 | 0:37:57 | |

one reason why vellum has always been a luxury good. | 0:37:57 | 0:38:00 | |

Some of the stock in this room will go on to be Acts of Parliament. | 0:38:03 | 0:38:07 | |

Today's Royal Family are customers too. | 0:38:07 | 0:38:10 | |

The marriage certificate for William and Kate | 0:38:10 | 0:38:12 | |

was written on vellum made here. | 0:38:12 | 0:38:14 | |

-So here we have the finished product now. -Amazing. | 0:38:16 | 0:38:19 | |

All that effort and energy and this is what you end up with. | 0:38:19 | 0:38:22 | |

-Feel that lovely smooth surface. -Absolutely amazing. | 0:38:22 | 0:38:25 | |

This is so exciting for me, | 0:38:25 | 0:38:27 | |

because I'm used to seeing finished manuscripts | 0:38:27 | 0:38:30 | |

with their ink and their illuminations, | 0:38:30 | 0:38:32 | |

and yet to see it like this - just pure and white and new - | 0:38:32 | 0:38:35 | |

it is just fantastic. | 0:38:35 | 0:38:36 | |

I really feel there's this passage of time taking place. | 0:38:36 | 0:38:41 | |

It's come from a life, from a calf, | 0:38:41 | 0:38:42 | |

-and it's going onto something else, isn't it? -Absolutely. | 0:38:42 | 0:38:45 | |

Long after everyone else is gone, this will still be here. | 0:38:45 | 0:38:50 | |

This is vellum as I'm used to encountering it. | 0:38:57 | 0:39:01 | |

And despite the fact it's a thousand years old, | 0:39:01 | 0:39:04 | |

you still get the sense that this was once a living creature. | 0:39:04 | 0:39:08 | |

You can feel the hair side underneath your fingertips. | 0:39:08 | 0:39:12 | |

And what's really remarkable is that, | 0:39:12 | 0:39:14 | |

despite the fact it's been used for centuries, | 0:39:14 | 0:39:18 | |

it's still so well preserved. | 0:39:18 | 0:39:21 | |

There's something extraordinary | 0:39:23 | 0:39:25 | |

about the contents of this manuscript too. | 0:39:25 | 0:39:28 | |

This time the key figure is not a king, but a queen. | 0:39:28 | 0:39:31 | |

It's Cnut's wife, Aelfgifu, or Emma. | 0:39:32 | 0:39:36 | |

And this book was made after Cnut's death. | 0:39:36 | 0:39:39 | |

It's a highly flattering biography of her and her husband, | 0:39:39 | 0:39:44 | |

and like the other manuscripts I've looked at, | 0:39:44 | 0:39:47 | |

there's a sense in which image is being manipulated here, | 0:39:47 | 0:39:50 | |

because Emma has commissioned it herself. | 0:39:50 | 0:39:54 | |

Cnut's death caused a power struggle. | 0:39:55 | 0:39:57 | |

The throne passed not to one of Emma's children, | 0:39:57 | 0:40:00 | |

pictured with her here, but to his son by a previous marriage. | 0:40:00 | 0:40:05 | |

Emma's clearly learnt the power of manuscripts | 0:40:06 | 0:40:09 | |

from her Royal relatives. This is her version of history, | 0:40:09 | 0:40:12 | |

and she's had it written | 0:40:12 | 0:40:14 | |

to ensure she and Cnut remain at the heart of it. | 0:40:14 | 0:40:17 | |

Their reign is described here as one of peace and prosperity, | 0:40:19 | 0:40:23 | |

in contrast to the bloody turmoil which ensued afterwards. | 0:40:23 | 0:40:27 | |

This text does everything it can to prove Emma's sons | 0:40:27 | 0:40:31 | |

are the rightful heirs to the throne. | 0:40:31 | 0:40:34 | |

In the end, both her sons did rule England. | 0:40:36 | 0:40:40 | |

But in this image, it's not the boys that are on the throne - | 0:40:40 | 0:40:43 | |

it's Emma herself. | 0:40:43 | 0:40:45 | |

It really strikes me what an important historical figure she is - | 0:40:45 | 0:40:49 | |

married to two kings and mother to two kings. | 0:40:49 | 0:40:52 | |

But it was another of Emma's relatives | 0:40:56 | 0:40:58 | |

who was to have the most dramatic effect on English history. | 0:40:58 | 0:41:01 | |

Emma had grown up in Normandy | 0:41:01 | 0:41:03 | |

and her great-nephew was called William. | 0:41:03 | 0:41:06 | |

The most famous imagery of the Norman Conquest, of course, | 0:41:11 | 0:41:14 | |

isn't on vellum, but on fabric. | 0:41:14 | 0:41:16 | |

The story told by the Bayeux Tapestry | 0:41:19 | 0:41:22 | |

not only spelt the end of the Anglo-Saxon Royal line, | 0:41:22 | 0:41:25 | |

but also caused a deep rupture in the story of England. | 0:41:25 | 0:41:29 | |

For generations to come, | 0:41:30 | 0:41:32 | |

this would prove a challenge to the makers of Royal manuscripts. | 0:41:32 | 0:41:35 | |

How do you present the Royal line as legitimate when its power was won | 0:41:35 | 0:41:40 | |

through such widespread cultural and political upheaval? | 0:41:40 | 0:41:44 | |

'This is one solution - the genealogical chronicle. | 0:41:55 | 0:41:59 | |

'Once the descendants of the Norman invaders had put down roots here, | 0:42:02 | 0:42:06 | |

'they wanted to prove that they too | 0:42:06 | 0:42:08 | |

'had their place in the Royal family tree.' | 0:42:08 | 0:42:11 | |

The artist that's worked on this genealogical roll | 0:42:16 | 0:42:19 | |

has come up with a number of different strategies to show | 0:42:19 | 0:42:22 | |

a continuity throughout the history of the English kings. | 0:42:22 | 0:42:27 | |

The language used for the manuscripts may now be French, | 0:42:28 | 0:42:32 | |

but the roll includes all the familiar names | 0:42:32 | 0:42:34 | |

of the Anglo-Saxon era, such as Edgar and Athelstan. | 0:42:34 | 0:42:38 | |

Around that most famous of dates, 1066, | 0:42:40 | 0:42:44 | |

the roll gets a little bit more confusing. | 0:42:44 | 0:42:46 | |

The last Anglo-Saxon king, Harold Godwinson, who died at Hastings, | 0:42:46 | 0:42:51 | |

is shown in isolation. | 0:42:51 | 0:42:53 | |

For the Normans, he had no legitimate claim to be king. | 0:42:53 | 0:42:57 | |

In contrast, we see here William the Bastard. | 0:42:57 | 0:43:01 | |

This is William The Conqueror. | 0:43:01 | 0:43:03 | |

And there's been a huge amount of effort made to connect him | 0:43:03 | 0:43:07 | |

to the other kings on the roll. | 0:43:07 | 0:43:09 | |

So we have this stand-alone section here showing William's heritage. | 0:43:09 | 0:43:14 | |

He's come from a strong line of Dukes of Normandy. | 0:43:14 | 0:43:18 | |

And following on from him, | 0:43:18 | 0:43:21 | |

we see this line coming out of his descendants | 0:43:21 | 0:43:25 | |

and connecting into future kings. | 0:43:25 | 0:43:27 | |

So here we have Henry, the first of the Plantagenet kings. | 0:43:27 | 0:43:31 | |

And there's been an attempt made to link him back | 0:43:31 | 0:43:33 | |

to the Anglo-Saxon monarchy, through his wife here, Queen Maud. | 0:43:33 | 0:43:38 | |

And if we follow this long blue line past the Normans, | 0:43:38 | 0:43:43 | |

past Cnut and Harthacnut, | 0:43:43 | 0:43:45 | |

we get back to this character - St Margaret, | 0:43:45 | 0:43:49 | |

a descendent of the Anglo-Saxon king Edmund Ironside. | 0:43:49 | 0:43:53 | |

This particular roll is almost five metres long, | 0:43:56 | 0:44:00 | |

and features 32 successive kings of England. | 0:44:00 | 0:44:03 | |

Dozens of other Royal family trees survive | 0:44:04 | 0:44:08 | |

from the 13th and 14th centuries. | 0:44:08 | 0:44:11 | |

Though they were made by a variety of scribes across England, | 0:44:11 | 0:44:14 | |

they all follow a common template, | 0:44:14 | 0:44:16 | |

using this graphic style | 0:44:16 | 0:44:18 | |

of depicting each of the monarchs as if on a coin. | 0:44:18 | 0:44:21 | |

And, unusually for this period, | 0:44:23 | 0:44:25 | |

we actually know the name of the artist | 0:44:25 | 0:44:27 | |

who first came up with this much-copied design. | 0:44:27 | 0:44:30 | |

Matthew Paris. He even left us this self-portrait. | 0:44:33 | 0:44:37 | |

As the haircut suggests, he was a monk. | 0:44:37 | 0:44:40 | |

He lived during the reign of Henry III | 0:44:41 | 0:44:44 | |

and exemplifies the confident Anglo-French culture of the era. | 0:44:44 | 0:44:48 | |

And he produced various kinds of chronicles, | 0:44:50 | 0:44:54 | |

including this, his Historia Anglorum. | 0:44:54 | 0:44:56 | |

Matthew Paris has been involved | 0:45:00 | 0:45:03 | |

in all aspects of creating this manuscript. | 0:45:03 | 0:45:06 | |

Not only is he the author - he's actually composed this text - | 0:45:06 | 0:45:09 | |

but this is his handwriting, so he's acting as scribe as well. | 0:45:09 | 0:45:13 | |

And then he's gone through | 0:45:13 | 0:45:15 | |

and illuminated and illustrated throughout. | 0:45:15 | 0:45:18 | |

There's some really lovely detailing where he's painted it too. | 0:45:18 | 0:45:23 | |

It's quite an exceptional feat for one man. | 0:45:23 | 0:45:25 | |

Among the illustrations are a hospital, and a man threshing. | 0:45:28 | 0:45:31 | |

They're clearly drawn from the contemporary world around him, | 0:45:31 | 0:45:36 | |

as is much of the text. | 0:45:36 | 0:45:38 | |

The majority of the work concerns Paris' own lifetime | 0:45:38 | 0:45:42 | |

and the king who ruled over him - Henry. | 0:45:42 | 0:45:45 | |

As we get towards the end, | 0:45:48 | 0:45:50 | |

Paris is writing about events almost as they're happening, | 0:45:50 | 0:45:54 | |

and he's also offering opinions on them. | 0:45:54 | 0:45:57 | |

So what we seem to be dealing with here is less like history | 0:45:57 | 0:46:00 | |

and more like journalism. | 0:46:00 | 0:46:02 | |

As a result, this work offers a view of monarchy | 0:46:02 | 0:46:06 | |

quite unlike anything that's gone before. | 0:46:06 | 0:46:09 | |

There are a number of points in this manuscript | 0:46:09 | 0:46:13 | |

where Paris is openly critical of Henry and his family. Here's one. | 0:46:13 | 0:46:17 | |

He's describing John, Henry's father, | 0:46:17 | 0:46:21 | |

and the taxation that he's imposing on the English people, | 0:46:21 | 0:46:25 | |

and he refers to him here as "tyrannus" - "tyrant". | 0:46:25 | 0:46:28 | |

That's pretty strong criticism of the king's father. | 0:46:28 | 0:46:32 | |

And it's seems it's so strong, perhaps, | 0:46:32 | 0:46:34 | |

that Paris has returned to the manuscript later, | 0:46:34 | 0:46:37 | |

and added this note, | 0:46:37 | 0:46:39 | |

"vacat" - "disregard". | 0:46:39 | 0:46:41 | |

Does this suggest that Paris knew he'd gone too far? | 0:46:43 | 0:46:47 | |

And look at this image here. | 0:46:49 | 0:46:51 | |

In its composition, it's saying something really telling | 0:46:51 | 0:46:55 | |

about the relationship between the Church and the King. | 0:46:55 | 0:46:58 | |

So you can see the Bishop, | 0:46:58 | 0:47:00 | |

the representative of the Church, is on a really stable footing. | 0:47:00 | 0:47:03 | |

And yet the King, King Henry, is teetering on the edge. | 0:47:03 | 0:47:08 | |

He's very contorted and unstable-looking. | 0:47:08 | 0:47:11 | |

It's not a very flattering image of him. | 0:47:11 | 0:47:13 | |

In many ways, it's a bit like a satirical cartoon. | 0:47:13 | 0:47:17 | |

Frankly, Paris reads less like a medieval scribe | 0:47:17 | 0:47:21 | |

and more like a modern author. | 0:47:21 | 0:47:24 | |

But how could this startlingly independent approach | 0:47:24 | 0:47:28 | |

have arisen in 13th-century Britain? | 0:47:28 | 0:47:30 | |

Matthew Paris lived and worked for most of his life | 0:47:36 | 0:47:40 | |

in St Albans Abbey, now the foundations of the town's cathedral. | 0:47:40 | 0:47:43 | |

On its walls are some 13th-century paintings. | 0:47:48 | 0:47:52 | |

Paris would have seen these. | 0:47:55 | 0:47:57 | |

In Medieval times, the abbey was a major site of pilgrimage. | 0:48:00 | 0:48:04 | |

And chief among the devout visitors was Henry III himself. | 0:48:07 | 0:48:12 | |

I think Matthew Paris is an absolutely unique chronicler | 0:48:14 | 0:48:18 | |

because of his relationship with the King. | 0:48:18 | 0:48:20 | |

He knows Henry III intimately. Henry III comes here, he meets Paris. | 0:48:20 | 0:48:26 | |

It's a curious relationship because, on the one hand, | 0:48:26 | 0:48:30 | |

Henry III says to Paris, "Write this, write that," | 0:48:30 | 0:48:33 | |

cos Henry III has this huge desire | 0:48:33 | 0:48:35 | |

to have the events of his reign recorded | 0:48:35 | 0:48:37 | |

and have his own great deeds recorded, and Paris does that. | 0:48:37 | 0:48:41 | |

On the other hand, if Henry had seen some of the things | 0:48:41 | 0:48:43 | |

Paris was writing, he would have been absolutely appalled. | 0:48:43 | 0:48:47 | |

Absolutely, yes. It is the most critical text we've had to date | 0:48:47 | 0:48:50 | |

of someone writing about a king, | 0:48:50 | 0:48:52 | |

and so there's this strange ambiguity and tension. | 0:48:52 | 0:48:55 | |

I think with Paris it's that God is working his purpose out in history, | 0:48:55 | 0:49:00 | |

and Paris feels it's absolutely obligatory on him | 0:49:00 | 0:49:04 | |

-to actually say what is good and what is bad. -Yes. | 0:49:04 | 0:49:07 | |

Because in God's history, some things are good and some are bad. | 0:49:07 | 0:49:10 | |

And I wonder, you know, whether at St Albans itself, | 0:49:10 | 0:49:14 | |

there was a party within the monks, | 0:49:14 | 0:49:16 | |

perhaps the Abbot himself, who deeply worried about Paris' tone. | 0:49:16 | 0:49:22 | |

And I think, in the end, | 0:49:22 | 0:49:23 | |

this may help to explain the extraordinary way | 0:49:23 | 0:49:26 | |

in which, very late in life, | 0:49:26 | 0:49:28 | |

Paris went through the work and excised a great deal. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:32 | |

Did it in a funny sort of way, | 0:49:32 | 0:49:33 | |

-because sometimes he stuck bits of paper... -Yes. | 0:49:33 | 0:49:35 | |

..over what he'd excised, | 0:49:35 | 0:49:37 | |

-so actually you can still lift it up... -And find the criticisms. | 0:49:37 | 0:49:40 | |

So, you know, you lift... | 0:49:40 | 0:49:42 | |

On the top, it says, "The venerable archbishop Boniface came | 0:49:42 | 0:49:45 | |

"and behaved in a dignified way," | 0:49:45 | 0:49:47 | |

and underneath it says, "The appalling archbishop Boniface | 0:49:47 | 0:49:51 | |

"took all our horses," and everything. | 0:49:51 | 0:49:53 | |

The volume I've seen was perhaps intended as a first draft, | 0:49:56 | 0:50:01 | |

to be copied again later without the offending passages. | 0:50:01 | 0:50:04 | |

And in his major portraits of the kings, Paris is much less critical. | 0:50:07 | 0:50:12 | |

They're imbued with the spirituality of their divine calling. | 0:50:12 | 0:50:17 | |

And Henry is glorified by his greatest act of piety - | 0:50:19 | 0:50:24 | |

the reconstruction of Westminster Abbey. | 0:50:24 | 0:50:27 | |

The greatest of Anglo-Saxon cathedrals had remained the centre | 0:50:35 | 0:50:40 | |

for Royal ritual, despite the Norman conquest of England. | 0:50:40 | 0:50:43 | |

Now it was assuming a grander, more awe-inspiring form, | 0:50:45 | 0:50:50 | |

much like the monarchy itself. | 0:50:50 | 0:50:52 | |

This must have been a really vibrant and stimulating place | 0:50:57 | 0:51:01 | |

in the mid-13th century. | 0:51:01 | 0:51:03 | |

Under Henry III, there was masses of building work taking place. | 0:51:03 | 0:51:07 | |

And alongside architecture, | 0:51:07 | 0:51:09 | |

there were other artistic activities based right here in Westminster. | 0:51:09 | 0:51:12 | |

The best English manuscript art was now being produced in London, | 0:51:21 | 0:51:25 | |

rather than in Winchester or Northumbria. | 0:51:25 | 0:51:28 | |

Some of the most stunning illustrations of this era | 0:51:34 | 0:51:37 | |

appear in psalters - | 0:51:37 | 0:51:38 | |

small, personal prayer books made from the Book of Psalms. | 0:51:38 | 0:51:43 | |

These had a particular relevance for Royal readers, | 0:51:46 | 0:51:50 | |

because they centred on a model of monarchy from the Bible. | 0:51:50 | 0:51:54 | |

King David combined two of the qualities of kingship | 0:51:54 | 0:51:57 | |

which Medieval England most valued. | 0:51:57 | 0:51:59 | |

Psalters were the perfect learning tool for a young prince, | 0:52:02 | 0:52:05 | |

because they could teach them | 0:52:05 | 0:52:07 | |

how to be pious rulers and valiant soldiers. | 0:52:07 | 0:52:09 | |

I've got one here that was custom-made | 0:52:09 | 0:52:11 | |

for an heir to the English throne. | 0:52:11 | 0:52:13 | |

It's a shining example of the 13th-century Westminster style. | 0:52:15 | 0:52:20 | |

The difference between this manuscript | 0:52:20 | 0:52:23 | |

and the other ones I've encountered | 0:52:23 | 0:52:25 | |

is that this one has been designed throughout | 0:52:25 | 0:52:28 | |

for the personal use of one individual Royal. | 0:52:28 | 0:52:31 | |

This psalter was commissioned as a wedding gift. | 0:52:34 | 0:52:37 | |

In 1284, King Edward I was preparing to celebrate | 0:52:37 | 0:52:42 | |

the marriage of his young son and heir, | 0:52:42 | 0:52:44 | |

the exotically-named Prince Alphonso. | 0:52:44 | 0:52:48 | |

He was engaged to a countess from Holland, | 0:52:48 | 0:52:51 | |

so next to England's coat of arms is her Dutch heraldry. | 0:52:51 | 0:52:54 | |

As was often the case at this time, | 0:52:57 | 0:52:59 | |

the groom was a boy of just ten years old. | 0:52:59 | 0:53:03 | |

And that's why the margins of this book are full of images | 0:53:03 | 0:53:07 | |

that would have appealed to a young prince, | 0:53:07 | 0:53:09 | |

like a man wrestling with a lion. | 0:53:09 | 0:53:13 | |

Compared to a typical psalter, | 0:53:15 | 0:53:16 | |

the images of battle here are fantastical. | 0:53:16 | 0:53:20 | |

At times, it's like a high-class comic book. | 0:53:20 | 0:53:24 | |

There are also images of fertility in here, | 0:53:24 | 0:53:27 | |

like a mermaid suckling her young. | 0:53:27 | 0:53:29 | |

These were seen as perfect for a wedding gift, | 0:53:29 | 0:53:32 | |

but are perhaps a little strange | 0:53:32 | 0:53:34 | |

when you remember that the groom is a prepubescent boy. | 0:53:34 | 0:53:38 | |

Other illustrations are probably references | 0:53:40 | 0:53:43 | |

to the opulent lifestyle of the Royal household. | 0:53:43 | 0:53:47 | |

Queen Eleanor kept lions in her menagerie, | 0:53:47 | 0:53:51 | |

while the aviary may have provided models | 0:53:51 | 0:53:53 | |

for these exquisitely delicate birds. | 0:53:53 | 0:53:56 | |

This really is one of the most beautiful manuscripts I've seen. | 0:53:58 | 0:54:02 | |

This use of gold and bright colours | 0:54:02 | 0:54:05 | |

is really in keeping with the fashion at court for lavish display. | 0:54:05 | 0:54:10 | |

Like any manuscript, many months of labour | 0:54:10 | 0:54:13 | |

would have gone into creating this exquisite work. | 0:54:13 | 0:54:17 | |

But the marriage that all this work was done for never took place. | 0:54:21 | 0:54:25 | |

Just months before the wedding day, the young prince died, | 0:54:25 | 0:54:28 | |

aged just ten years old, | 0:54:28 | 0:54:31 | |

and work on the psalter ceased. | 0:54:31 | 0:54:33 | |

The margins, so richly decorated in the early pages, | 0:54:36 | 0:54:40 | |

are suddenly left painfully blank. | 0:54:40 | 0:54:43 | |

Yet an unlikely set of circumstances | 0:54:47 | 0:54:50 | |

meant that this book did eventually have a second life. | 0:54:50 | 0:54:54 | |

Some 15 years later, | 0:54:54 | 0:54:56 | |

Alphonso's sister became engaged to his fiancee's brother. | 0:54:56 | 0:55:00 | |

The arms of Holland and England that feature in this beautiful book | 0:55:00 | 0:55:05 | |

would finally be united. | 0:55:05 | 0:55:07 | |

It's proof of just how valuable these objects were, | 0:55:10 | 0:55:12 | |

that someone was keen to make use of all the work | 0:55:12 | 0:55:15 | |

which had already been done. | 0:55:15 | 0:55:17 | |

Alphonso, meanwhile, | 0:55:24 | 0:55:26 | |

rests to this day in the most sacred chapel of Westminster Abbey, | 0:55:26 | 0:55:30 | |

near both his father Edward and his grandfather Henry III. | 0:55:30 | 0:55:34 | |

By the time this part of the Abbey was built in the late 13th century, | 0:55:36 | 0:55:40 | |

the English monarchy seemed permanent and assured. | 0:55:40 | 0:55:44 | |

Set in stone, in fact, and brass. | 0:55:46 | 0:55:50 | |

It had come a long way since Athelstan began to define | 0:55:52 | 0:55:56 | |

what a king of England could be. | 0:55:56 | 0:55:58 | |

One English monarch had even been elevated to sainthood - | 0:55:58 | 0:56:03 | |

Edward the Confessor's shrine was the centrepiece | 0:56:03 | 0:56:06 | |

of the new Westminster. | 0:56:06 | 0:56:08 | |

Religious and Royal power remained intertwined | 0:56:11 | 0:56:14 | |

in the architecture and the rituals of the Abbey, | 0:56:14 | 0:56:17 | |

and in its manuscripts. | 0:56:17 | 0:56:20 | |

Above all, in the coronation book. | 0:56:20 | 0:56:23 | |

We've got so much going on here in terms of the centuries | 0:56:25 | 0:56:29 | |

of manipulating kingly imagery that we've seen in earlier manuscripts. | 0:56:29 | 0:56:35 | |

Here we have a joint coronation going on. | 0:56:35 | 0:56:38 | |

In this instance, | 0:56:38 | 0:56:39 | |

we're looking at Richard the II and his wife Anne of Bohemia. | 0:56:39 | 0:56:43 | |

The King and the Queen have all this regalia. | 0:56:43 | 0:56:46 | |

They have these enormous crowns on their heads, | 0:56:46 | 0:56:49 | |

and the whole composition is really showing | 0:56:49 | 0:56:53 | |

the sanctification of the King and Queen. | 0:56:53 | 0:56:56 | |

You can see there are these archbishops - | 0:56:56 | 0:56:58 | |

the archbishops of York and Canterbury - | 0:56:58 | 0:57:01 | |

framing the King and his queen, | 0:57:01 | 0:57:03 | |

making them seem divine, even. And anyone looking at this image | 0:57:03 | 0:57:09 | |

would call to mind the coronation | 0:57:09 | 0:57:10 | |

of Edward the Confessor, the saintly king. | 0:57:10 | 0:57:13 | |

He was crowned by both the archbishops of York and Canterbury, | 0:57:13 | 0:57:18 | |

so all future coronations are harking back to this earlier one, | 0:57:18 | 0:57:21 | |

this ideal one. | 0:57:21 | 0:57:22 | |

And the use of gold - | 0:57:24 | 0:57:26 | |

it's just absolutely absorbing them into this divinity, | 0:57:26 | 0:57:31 | |

this wealth, this absolute image of power. | 0:57:31 | 0:57:36 | |

The manuscripts of the English monarchy | 0:57:43 | 0:57:46 | |

did so much more than just record knowledge and bequeath us portraits. | 0:57:46 | 0:57:51 | |

Over the centuries, when England was first formed, then conquered, | 0:57:51 | 0:57:57 | |

they gave legitimacy and continuity to a succession of rulers. | 0:57:57 | 0:58:01 | |

Manuscripts defined the image of the English monarchy. | 0:58:03 | 0:58:07 | |

They shaped its role, and they communicated its meaning. | 0:58:07 | 0:58:10 | |

They did that in ways which formed this kingdom in their lifetimes... | 0:58:10 | 0:58:14 | |

..and which are still with us today. | 0:58:16 | 0:58:18 | |

Next time... | 0:58:26 | 0:58:27 | |

In an age of plague, rebellion, | 0:58:27 | 0:58:30 | |

and a Hundred Years' War with France - | 0:58:30 | 0:58:35 | |

how manuscripts taught kings the tools of their trade. | 0:58:35 | 0:58:38 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:58:58 | 0:59:02 |