What a King Should Know Illuminations: The Private Lives of Medieval Kings

Similar Content

Browse content similar to What a King Should Know. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Somewhere out there in the 1420s, | 0:00:07 | 0:00:10 | |

a ship laden with war booty made its way slowly to the shore. | 0:00:10 | 0:00:15 | |

The great chests were unloaded carefully | 0:00:18 | 0:00:21 | |

and taken by cartload to London under heavy guard. | 0:00:21 | 0:00:24 | |

But these were no ordinary spoils of war. | 0:00:26 | 0:00:30 | |

This wasn't silver or gold, or even prisoners for ransom. | 0:00:30 | 0:00:35 | |

This was the physical theft of a nation's culture and history. | 0:00:35 | 0:00:40 | |

What was being landed was a cargo of manuscripts - | 0:00:45 | 0:00:49 | |

the greatest literary treasures of the French royal family | 0:00:49 | 0:00:52 | |

were now on their way to the English court. | 0:00:52 | 0:00:55 | |

After 80 years of war, England was victorious | 0:00:55 | 0:00:59 | |

and at the very heart of Europe. | 0:00:59 | 0:01:02 | |

We still have these captured manuscripts. | 0:01:04 | 0:01:07 | |

They are some of the most wonderful creations | 0:01:07 | 0:01:10 | |

of the late medieval period, | 0:01:10 | 0:01:12 | |

and they show England's ascendancy in Europe | 0:01:12 | 0:01:15 | |

during the Hundred Years War. | 0:01:15 | 0:01:17 | |

They also show a period of crisis from the 1320s to the 1450s, | 0:01:18 | 0:01:23 | |

when English kings had to triumph over rebellion and plague | 0:01:23 | 0:01:27 | |

to become worthy of the name "king". | 0:01:27 | 0:01:30 | |

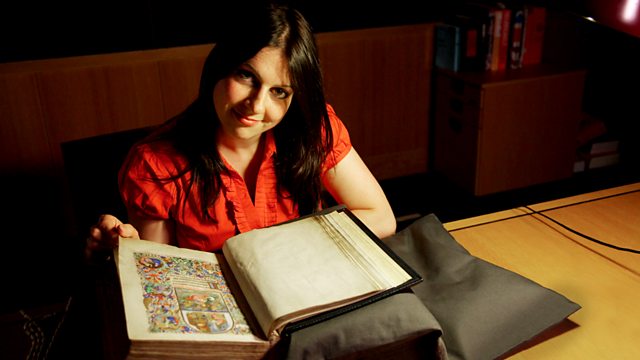

For this series, I've been given unrivalled access | 0:01:33 | 0:01:37 | |

to the crown jewels of illumination - | 0:01:37 | 0:01:39 | |

the Royal Manuscript Collection at the British Library. | 0:01:39 | 0:01:44 | |

These books are miraculous survivors, | 0:01:46 | 0:01:50 | |

which few people have ever seen - apart from monarchs. | 0:01:50 | 0:01:53 | |

They were custom-made for kings, they're about kings, | 0:01:53 | 0:01:57 | |

and they were read by kings. | 0:01:57 | 0:01:59 | |

I'll be exploring the world which created these manuscripts. | 0:02:01 | 0:02:05 | |

I'll be going to the places where they were made. | 0:02:08 | 0:02:11 | |

And discovering what they reveal about the centuries of conflict | 0:02:13 | 0:02:18 | |

when England was forged. | 0:02:18 | 0:02:20 | |

It's the story of monarchy which spans six centuries, | 0:02:20 | 0:02:25 | |

from the Anglo-Saxons to the Tudors. | 0:02:25 | 0:02:28 | |

In this episode, I'm going to reveal how manuscripts were used | 0:02:29 | 0:02:33 | |

to create a model of kingship that was boldly English | 0:02:33 | 0:02:37 | |

and epitomised by the soldier king, Henry V. | 0:02:37 | 0:02:41 | |

I'm seeing where these captured French manuscripts ended up. | 0:03:03 | 0:03:06 | |

It's the first time I have seen the spoils | 0:03:06 | 0:03:09 | |

of the French royal library and I can't wait to set eyes on them. | 0:03:09 | 0:03:13 | |

Many of the French books became the personal property | 0:03:15 | 0:03:19 | |

of the English monarchy and have stayed locked away for centuries | 0:03:19 | 0:03:23 | |

in the Royal Manuscript Collection. | 0:03:23 | 0:03:26 | |

George II gave the collection to the nation in 1757 | 0:03:26 | 0:03:30 | |

and now they are housed deep in the vaults of the British Library. | 0:03:30 | 0:03:34 | |

-Wow, it's a massive manuscript. -Yes, it's quite heavy. -Yes. | 0:03:34 | 0:03:39 | |

There's one in particular, | 0:03:39 | 0:03:41 | |

with an incredible history, that I've been dying to see. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:44 | |

This is the Grandes Chroniques de France - | 0:03:56 | 0:04:00 | |

the history of the French nation, a stupendous manuscript | 0:04:00 | 0:04:05 | |

written in the 1330s with over 400 images | 0:04:05 | 0:04:08 | |

detailing the great deeds of the French kings. | 0:04:08 | 0:04:12 | |

There are pictures of everything a king should be - | 0:04:14 | 0:04:17 | |

supreme military commander, law-maker, | 0:04:17 | 0:04:20 | |

dynast, and arbiter of the nation's taste. | 0:04:20 | 0:04:24 | |

It's a work that deliberately tells us | 0:04:25 | 0:04:28 | |

that only French kings are fit to rule. | 0:04:28 | 0:04:31 | |

In contrast, these shelves also contain | 0:04:33 | 0:04:36 | |

the history of the kings of England | 0:04:36 | 0:04:38 | |

by the chronicler Peter of Langtoft, | 0:04:38 | 0:04:41 | |

written just a few years earlier, | 0:04:41 | 0:04:44 | |

at the end of the reign of Edward II. | 0:04:44 | 0:04:46 | |

Like the Grandes Chroniques, albeit in its own small way, | 0:04:46 | 0:04:50 | |

it also tries to show everything a king should be. | 0:04:50 | 0:04:55 | |

Here we see real depictions of strong kings. | 0:04:57 | 0:05:00 | |

We have, at the front, King Arthur. | 0:05:00 | 0:05:03 | |

He's wearing a golden crown, | 0:05:03 | 0:05:05 | |

he has his shield emblazoned with an image of the Virgin, | 0:05:05 | 0:05:08 | |

and at his side, the famous sword Excalibur. | 0:05:08 | 0:05:13 | |

We can also see, beneath his feet, | 0:05:13 | 0:05:15 | |

crowns representing the kingdoms that he was the king of. | 0:05:15 | 0:05:18 | |

And as we go on, another strong English king, | 0:05:18 | 0:05:24 | |

Richard the Lionheart, also holding a sword - Excalibur again, in fact. | 0:05:24 | 0:05:29 | |

And as we go on, we find Edward I - hammer of the Scots and the Welsh. | 0:05:29 | 0:05:35 | |

But the last entry tells us something more | 0:05:38 | 0:05:40 | |

about the state of the English monarchy. | 0:05:40 | 0:05:43 | |

Something's happened to the manuscript - | 0:05:44 | 0:05:46 | |

it's where the official bit of praise would have been, | 0:05:46 | 0:05:49 | |

honouring the king, this has been scrubbed out, | 0:05:49 | 0:05:52 | |

it's damaged the manuscript quite badly, and in its place | 0:05:52 | 0:05:56 | |

we have some of the most abject words ascribed to an English king - | 0:05:56 | 0:06:00 | |

"Home m'appele roys abatu, e tout le secle me va gabaunt." | 0:06:00 | 0:06:08 | |

I'm going to discover what this extraordinary footnote is about | 0:06:08 | 0:06:12 | |

and what it meant for the English crown. | 0:06:12 | 0:06:15 | |

It's 1322 and the English monarchy has been defeated, | 0:06:22 | 0:06:28 | |

first in Scotland and then on the Welsh border. | 0:06:28 | 0:06:30 | |

Even worse is the loss of English lands in France. | 0:06:30 | 0:06:35 | |

But the most shocking event, at the heart of it all, | 0:06:35 | 0:06:38 | |

is that the English King, Edward II, has been deposed | 0:06:38 | 0:06:42 | |

and locked up here at Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire | 0:06:42 | 0:06:46 | |

where he fears he will be murdered. | 0:06:46 | 0:06:48 | |

Never before has a divinely anointed reigning king | 0:06:51 | 0:06:54 | |

been knocked from power in this way. | 0:06:54 | 0:06:57 | |

These are dangerous times for the English monarchy. | 0:06:57 | 0:07:00 | |

This is the very cell where Edward II was incarcerated. | 0:07:09 | 0:07:14 | |

I can just imagine him in here, penning the poignant lines | 0:07:14 | 0:07:17 | |

we find at the end of Peter of Langtoft's chronicles | 0:07:17 | 0:07:20 | |

of the great deeds of the English kings. | 0:07:20 | 0:07:22 | |

They provide a unique window into his soul. | 0:07:22 | 0:07:26 | |

"Home m'appele roys abatu, e tout le secle me va gabaunt." | 0:07:27 | 0:07:32 | |

"I am called the tumbledown king, and all the world mocks me." | 0:07:32 | 0:07:37 | |

Whether Edward II wrote those lines himself | 0:07:44 | 0:07:46 | |

or whether they were added by his enemies for propaganda purposes, | 0:07:46 | 0:07:50 | |

it's clear that the governance of England is broken | 0:07:50 | 0:07:54 | |

and the country is racked with crisis. | 0:07:54 | 0:07:57 | |

The running of the country has been hijacked by Sir Roger Mortimer, | 0:07:57 | 0:08:02 | |

the queen's lover, and his supporters. | 0:08:02 | 0:08:06 | |

And with the king incarcerated, | 0:08:06 | 0:08:07 | |

the young prince, who will become Edward III, faces a fearful future. | 0:08:07 | 0:08:12 | |

His task will be to rebuild the power | 0:08:14 | 0:08:16 | |

and reputation of the English monarchy, if he possibly can. | 0:08:16 | 0:08:20 | |

But how? | 0:08:22 | 0:08:23 | |

Long before Machiavelli, there were manuals for princes. | 0:08:28 | 0:08:32 | |

One survives in the British Library | 0:08:32 | 0:08:34 | |

that was given to the young Edward by a noble, Walter Milmete. | 0:08:34 | 0:08:38 | |

I'm looking here at a wonderful manuscript | 0:08:39 | 0:08:42 | |

made around 1327 for the king-to-be, Edward III. | 0:08:42 | 0:08:47 | |

It's called the Secretum Secretorum, a mirror for princes. | 0:08:47 | 0:08:50 | |

This work was thought in medieval times | 0:08:52 | 0:08:55 | |

to have been originally written for Alexander the Great by his tutor, | 0:08:55 | 0:08:59 | |

the philosopher Aristotle. | 0:08:59 | 0:09:01 | |

It contains everything that a prince would need to know | 0:09:02 | 0:09:05 | |

in order to be a good ruler and follow in the example | 0:09:05 | 0:09:08 | |

of someone as magnificent as Alexander the Great. | 0:09:08 | 0:09:11 | |

Everything from statecraft to history, medicine to astrology. | 0:09:11 | 0:09:15 | |

It emphasises things like Christian virtue, | 0:09:15 | 0:09:19 | |

chivalric or knightly values. | 0:09:19 | 0:09:22 | |

And there's also images instructing the young king | 0:09:22 | 0:09:25 | |

on how he should best govern, | 0:09:25 | 0:09:27 | |

so here we have an enthroned king receiving the advice of his peers - | 0:09:27 | 0:09:32 | |

we've got knights and clergymen bringing him advice. | 0:09:32 | 0:09:36 | |

For me, one of the most exciting things about seeing a book like this | 0:09:36 | 0:09:41 | |

is the thought that it's imparting knowledge to a king, | 0:09:41 | 0:09:45 | |

it's telling him information about things he needs to know about. | 0:09:45 | 0:09:49 | |

To think that the young Edward III, only a boy of 14, | 0:09:49 | 0:09:53 | |

might have turned these very pages. | 0:09:53 | 0:09:56 | |

It reveals an awful lot about the moment at which Edward III | 0:09:57 | 0:10:02 | |

is going to be taking on the throne. | 0:10:02 | 0:10:04 | |

If we look at this image here, we can see the messenger | 0:10:04 | 0:10:07 | |

that's holding the book can be identified as Edward III, | 0:10:07 | 0:10:11 | |

he's wearing his coat-of-arms on his buckle. | 0:10:11 | 0:10:14 | |

He's there in this position, between philosopher and great ruler, | 0:10:14 | 0:10:19 | |

absorbing the knowledge that's contained within this work. | 0:10:19 | 0:10:23 | |

It really feels like a living document, | 0:10:23 | 0:10:25 | |

we can see these pages remain unfinished, | 0:10:25 | 0:10:28 | |

they're still being painted in, | 0:10:28 | 0:10:30 | |

and there's images of warcraft, weaponry, | 0:10:30 | 0:10:35 | |

and over the page, we have this very early image of a cannon. | 0:10:35 | 0:10:40 | |

This was added some time after the book was originally written. | 0:10:41 | 0:10:46 | |

It's an important clue to the young king's future mindset. | 0:10:46 | 0:10:50 | |

As are the next pages, which feature archers. | 0:10:50 | 0:10:55 | |

Incomplete, but significant. | 0:10:55 | 0:10:57 | |

But there's definitely a darker side to this manuscript. | 0:10:59 | 0:11:03 | |

As much as it's clearly intended for the young king | 0:11:03 | 0:11:06 | |

and it shows his coat-of-arms throughout, | 0:11:06 | 0:11:08 | |

there are other coats-of-arms also depicted alongside. | 0:11:08 | 0:11:11 | |

Here, those of his uncles, and over the page, | 0:11:11 | 0:11:16 | |

that of his mother, Queen Isabella, | 0:11:16 | 0:11:19 | |

who, along with her lover, Roger Mortimer and these uncles, | 0:11:19 | 0:11:24 | |

were responsible for removing his father, Edward II, from the throne. | 0:11:24 | 0:11:28 | |

What this says to me is, it's a warning, really. | 0:11:28 | 0:11:32 | |

It's saying to the young Edward III, | 0:11:32 | 0:11:34 | |

"Be careful, these same people can depose you too." | 0:11:34 | 0:11:38 | |

I've come to meet Ian Mortimer, | 0:11:50 | 0:11:53 | |

who's a biographer of Edward III and other late medieval kings. | 0:11:53 | 0:11:57 | |

So what's the situation | 0:11:59 | 0:12:01 | |

that Edward III finds himself in at the beginning of his reign? | 0:12:01 | 0:12:05 | |

If you want an image of him, picture a 14-year-old boy on a throne | 0:12:05 | 0:12:09 | |

clad in all the clothes of state, | 0:12:09 | 0:12:12 | |

the crown, the sceptre, the orb, | 0:12:12 | 0:12:14 | |

really quite terrified about all the people around him. | 0:12:14 | 0:12:16 | |

The court is populated by his enemies, | 0:12:16 | 0:12:19 | |

he can't stop them elevating their friends. | 0:12:19 | 0:12:21 | |

He can't stop Roger Mortimer, for example, in 1328, | 0:12:21 | 0:12:24 | |

giving up Scotland in the shameful Treaty of Northampton. | 0:12:24 | 0:12:28 | |

And he wants to do something about that. | 0:12:28 | 0:12:31 | |

He wants to re-impose regal authority and dignity. | 0:12:31 | 0:12:34 | |

He wants to create a new vision of kingship. | 0:12:34 | 0:12:36 | |

How difficult is it to be a successful medieval king? | 0:12:36 | 0:12:40 | |

Being a medieval king is enormously difficult. | 0:12:40 | 0:12:43 | |

Your basic job spec, if you want to use that term, | 0:12:43 | 0:12:46 | |

is to be a good law-giver. | 0:12:46 | 0:12:48 | |

To be fair to all your leading men, all your lords, all your bishops. | 0:12:48 | 0:12:53 | |

You have to be strong militarily | 0:12:53 | 0:12:55 | |

and that is not just strong against the French or against the Scots, | 0:12:55 | 0:12:59 | |

you've got to be strong in keeping all the rebels under control. | 0:12:59 | 0:13:02 | |

But everything's going to fail if you aren't strong militarily. | 0:13:02 | 0:13:07 | |

If you allow the rebels to fight and if you're defeated by the French, | 0:13:07 | 0:13:11 | |

you are going to fail as a monarch. | 0:13:11 | 0:13:14 | |

But it seems Edward already had a plan. | 0:13:17 | 0:13:21 | |

He gathered together a band of young, loyal knights - | 0:13:21 | 0:13:25 | |

a band of brothers, if you like - men he felt he could trust. | 0:13:25 | 0:13:30 | |

They captured Mortimer and he was brought to London, | 0:13:30 | 0:13:33 | |

tried, and executed. | 0:13:33 | 0:13:35 | |

The truth was, Edward already had his own model of kingship in mind. | 0:13:42 | 0:13:48 | |

I've come to the ancient city of Winchester to see the artefact | 0:13:59 | 0:14:03 | |

that gives witness to Edward's plan. | 0:14:03 | 0:14:05 | |

This is the symbol of kingship | 0:14:07 | 0:14:09 | |

that the young Edward III could most relate to - | 0:14:09 | 0:14:13 | |

King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. | 0:14:13 | 0:14:16 | |

This is a 13th-century table | 0:14:16 | 0:14:19 | |

made of English oak by his grandfather Edward I. | 0:14:19 | 0:14:23 | |

And it's the perfect model for the relationship | 0:14:23 | 0:14:26 | |

between the king and his noblemen. | 0:14:26 | 0:14:28 | |

King Arthur's depicted at the top | 0:14:28 | 0:14:30 | |

and there are 24 place settings around the edge, | 0:14:30 | 0:14:32 | |

and the fact it's a circle | 0:14:32 | 0:14:34 | |

means that there's no precedence. Every nobleman is equal. | 0:14:34 | 0:14:37 | |

This was certainly a model of kingship | 0:14:37 | 0:14:40 | |

that appealed to the noblemen at the time. | 0:14:40 | 0:14:44 | |

Coming out of the chaos of his father's reign, | 0:14:44 | 0:14:47 | |

this offered a sense of stability to everyone. | 0:14:47 | 0:14:50 | |

The symbolism of the table, with the wise king at the head | 0:14:53 | 0:14:57 | |

and all the nobles seated around him, without order of precedence, | 0:14:57 | 0:15:01 | |

was born of a collective wish that things genuinely could be this way. | 0:15:01 | 0:15:06 | |

The Arthurian model crops up continuously in this period, | 0:15:07 | 0:15:11 | |

and that's why we saw Arthur | 0:15:11 | 0:15:13 | |

at the head of Edwards II's lineage of kings. | 0:15:13 | 0:15:16 | |

Although nowadays we see him as a semi-mythological figure, | 0:15:17 | 0:15:21 | |

in medieval times, Arthur was thought to have been a real king | 0:15:21 | 0:15:25 | |

and the architect of the perfect polity, | 0:15:25 | 0:15:28 | |

in which wisdom is shared | 0:15:28 | 0:15:30 | |

and each of the participants are aware of their own responsibilities | 0:15:30 | 0:15:35 | |

to each other in chivalric, or knightly, virtue. | 0:15:35 | 0:15:39 | |

But for Edward III, this wasn't just a symbol of kingship, | 0:15:40 | 0:15:43 | |

he made it a reality. | 0:15:43 | 0:15:45 | |

He spent lavish amounts on feasting, jousting, and tournaments. | 0:15:47 | 0:15:52 | |

All of this was designed to bring the noblemen around him | 0:15:52 | 0:15:55 | |

and create a training ground for them. | 0:15:55 | 0:15:58 | |

But the underlying reason for this | 0:15:58 | 0:16:00 | |

was to avoid the errors of his father's reign | 0:16:00 | 0:16:03 | |

and keep potentially rebellious factions close to hand. | 0:16:03 | 0:16:07 | |

A really brutal victory over the Scots at Halidon Hill in 1333 | 0:16:13 | 0:16:19 | |

and the consolidation of peace at home | 0:16:19 | 0:16:21 | |

shows that Edward's new discipline is working. | 0:16:21 | 0:16:24 | |

He is proving a tough and wise young king. | 0:16:25 | 0:16:28 | |

On the other side of the English Channel, | 0:16:30 | 0:16:32 | |

the French also have cause for concern. | 0:16:32 | 0:16:35 | |

Their own king has died childless and the new Valois line | 0:16:36 | 0:16:40 | |

that has taken the French throne | 0:16:40 | 0:16:42 | |

is aware that Edward III has a rival claim | 0:16:42 | 0:16:45 | |

through his mother, Isabella of France. | 0:16:45 | 0:16:48 | |

The battle for dominance in Europe | 0:16:50 | 0:16:52 | |

between those ancient rivals, England and France, | 0:16:52 | 0:16:55 | |

was now to be fought not only on the battlefields of France, | 0:16:55 | 0:16:59 | |

but also in the pages of heavily illuminated manuscripts. | 0:16:59 | 0:17:03 | |

That's why I'm returning to the Grandes Chroniques, | 0:17:06 | 0:17:09 | |

one of the captured French manuscripts. | 0:17:09 | 0:17:12 | |

It was made in the 1330s | 0:17:14 | 0:17:16 | |

and commissioned by the heir to the French throne, John de Valois. | 0:17:16 | 0:17:21 | |

It has one single-minded purpose - | 0:17:22 | 0:17:25 | |

to establish the new Valois dynasty as rightful kings of France | 0:17:25 | 0:17:29 | |

over the competing claims of Edward III. | 0:17:29 | 0:17:32 | |

If we look at the frontispiece, | 0:17:34 | 0:17:37 | |

here we see a gallery of monarchs | 0:17:37 | 0:17:40 | |

whose succession is determined not by blood, | 0:17:40 | 0:17:42 | |

but by the right to occupy the pedestal of kingship. | 0:17:42 | 0:17:47 | |

It's one of the most heavily illustrated | 0:17:50 | 0:17:53 | |

of all 14th-century manuscripts, and it also tells me | 0:17:53 | 0:17:57 | |

that the French, too, are recreating the chivalric ideal. | 0:17:57 | 0:18:01 | |

The book is festooned with images of French knights | 0:18:05 | 0:18:09 | |

following their king in battle - | 0:18:09 | 0:18:11 | |

enough to overpower any English pretensions to greatness. | 0:18:11 | 0:18:15 | |

To me, this whole work is a powerful piece of PR. | 0:18:17 | 0:18:21 | |

It can be used as a propaganda tool | 0:18:21 | 0:18:23 | |

and I can imagine it being brought out to impress visiting dignitaries. | 0:18:23 | 0:18:29 | |

It's possible that Edward himself was aware of this manuscript | 0:18:29 | 0:18:32 | |

and would have been very impressed by its magnificence. | 0:18:32 | 0:18:37 | |

Let's not forget, Edward sees his claim to the French throne as valid, | 0:18:38 | 0:18:42 | |

and this heritage should be his | 0:18:42 | 0:18:45 | |

by dynastic and legal right. | 0:18:45 | 0:18:48 | |

We think of England as very separate from France, | 0:18:50 | 0:18:53 | |

it wasn't for a very long time, | 0:18:53 | 0:18:55 | |

and in fact many kings of England had more affinity with France | 0:18:55 | 0:18:59 | |

and their domains in France than they had in England. | 0:18:59 | 0:19:03 | |

So this is very natural, looking to the continent. | 0:19:03 | 0:19:08 | |

The Channel is not... | 0:19:08 | 0:19:11 | |

that sort of blockade, it's not a barrier. | 0:19:11 | 0:19:15 | |

It's very much a conduit between the two countries. | 0:19:15 | 0:19:18 | |

So, is there a French equivalent | 0:19:18 | 0:19:21 | |

of the Arthurian myth across the Channel? | 0:19:21 | 0:19:23 | |

Well, the Arthurian myth has a huge appeal on both sides, | 0:19:23 | 0:19:27 | |

partly because of the subject matter - | 0:19:27 | 0:19:31 | |

it appeals to the nobility on both sides, | 0:19:31 | 0:19:34 | |

and this idea of the Round Table | 0:19:34 | 0:19:36 | |

and this sort of brotherhood that support the king | 0:19:36 | 0:19:41 | |

is very critical both to Edward and to his French counterparts. | 0:19:41 | 0:19:48 | |

So there's a domestic agenda in how it applies to the own country, | 0:19:48 | 0:19:54 | |

but there's also a competition as well between them | 0:19:54 | 0:20:00 | |

as to which, in a sense, is the real Arthur. | 0:20:00 | 0:20:03 | |

-Absolutely. -You know, who is the equivalent. | 0:20:03 | 0:20:08 | |

The war of words over Edward's claim to the throne of France | 0:20:12 | 0:20:16 | |

simmers for years. | 0:20:16 | 0:20:18 | |

In the back of his mind, he knows that as king, he has the moral duty | 0:20:18 | 0:20:22 | |

in front of all his subjects to assert his dynastic rights. | 0:20:22 | 0:20:28 | |

He will never fully consolidate his power | 0:20:28 | 0:20:30 | |

over the nobles until he does so. | 0:20:30 | 0:20:32 | |

In 1337, a long-standing land dispute in Gascony | 0:20:32 | 0:20:38 | |

gives Edward his opportunity, | 0:20:38 | 0:20:41 | |

and a series of campaigns in France begins. | 0:20:41 | 0:20:44 | |

But it's nine years before Edward delivers his knockout blow. | 0:20:46 | 0:20:51 | |

It was from here, Portchester Castle, | 0:20:52 | 0:20:55 | |

that Edward III sailed with 15,000 men in 1346. | 0:20:55 | 0:21:00 | |

But it wasn't Gascony he sailed for, it was Normandy. | 0:21:00 | 0:21:04 | |

He was going to challenge the French king head on. | 0:21:04 | 0:21:07 | |

Relations between the two nations would never be the same again, | 0:21:07 | 0:21:12 | |

and the Channel would act as a line of division rather than a conduit. | 0:21:12 | 0:21:15 | |

The English armies begin a trail of destruction and pillage | 0:21:23 | 0:21:26 | |

across northern France. | 0:21:26 | 0:21:29 | |

And when Edward meets the French king at the Battle of Crecy, | 0:21:29 | 0:21:33 | |

there's a legendary victory | 0:21:33 | 0:21:35 | |

ensured by the longbows of the English archers. | 0:21:35 | 0:21:39 | |

He has a smaller army and he has this very calculated thing. | 0:21:42 | 0:21:46 | |

With archers, with projectile weaponry, | 0:21:46 | 0:21:48 | |

and with a few cannon, he takes on this massive army | 0:21:48 | 0:21:52 | |

and wins in a very calculated fashion, | 0:21:52 | 0:21:55 | |

and shock waves run throughout Europe | 0:21:55 | 0:21:58 | |

and Europe's really never been the same since. | 0:21:58 | 0:22:01 | |

In the margins of the Secretum Secretorum, there's cannons. | 0:22:01 | 0:22:04 | |

This is technology that Edward's employing in the battle? | 0:22:04 | 0:22:07 | |

That is the earliest representation of a cannon, | 0:22:07 | 0:22:09 | |

which then shot bolts in those days, | 0:22:09 | 0:22:11 | |

but Edward is the person who changes what cannon are. | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

He has this vision, that a small, well-equipped, | 0:22:14 | 0:22:17 | |

well-financed army can take on a much larger one | 0:22:17 | 0:22:21 | |

and win through projectile warfare. | 0:22:21 | 0:22:23 | |

You don't attack people hand-to-hand, | 0:22:23 | 0:22:25 | |

you shoot them before they get to you. It's very simple, really. | 0:22:25 | 0:22:29 | |

One single order in 1341 is for three million arrows, | 0:22:29 | 0:22:33 | |

so it's down to him that this technology exists. | 0:22:33 | 0:22:36 | |

It took five years to make those three million arrows. | 0:22:38 | 0:22:42 | |

This is why Edward delayed so long. | 0:22:42 | 0:22:46 | |

After all the insecurity of his youth, | 0:22:46 | 0:22:48 | |

he needed to make sure there was no chance of defeat. | 0:22:48 | 0:22:52 | |

So he's really reached the height of his game at this point? | 0:22:52 | 0:22:57 | |

The height of all games! | 0:22:57 | 0:22:59 | |

He has created a new example of the heights that kingship can reach. | 0:22:59 | 0:23:03 | |

Even 300 years later, people were writing about Edward | 0:23:03 | 0:23:06 | |

as perhaps the greatest king there had ever been. | 0:23:06 | 0:23:09 | |

With such success, | 0:23:17 | 0:23:19 | |

you would have thought that Edward's use of the Arthurian myth | 0:23:19 | 0:23:23 | |

had finally solved the problem of controlling his barons. | 0:23:23 | 0:23:28 | |

Indeed, throughout his long reign, | 0:23:28 | 0:23:31 | |

his nobles emulated him by acquiring manuscripts | 0:23:31 | 0:23:34 | |

detailing the exploits of Arthur's knights. | 0:23:34 | 0:23:37 | |

But they also added their own pages. | 0:23:40 | 0:23:43 | |

Men like Humphrey de Bohun liked their king powerful | 0:23:43 | 0:23:47 | |

but not TOO powerful. | 0:23:47 | 0:23:48 | |

Wow, gosh! Look at that amazing illumination. | 0:23:52 | 0:23:55 | |

This is a copy of Lancelot du Lac, | 0:23:55 | 0:23:58 | |

it's a French manuscript made around 1320 | 0:23:58 | 0:24:01 | |

and it's later acquired by Humphrey de Bohun, | 0:24:01 | 0:24:05 | |

who's one of the king's greatest earls, | 0:24:05 | 0:24:07 | |

and here, on this frontispiece that he's had added, | 0:24:07 | 0:24:10 | |

you can see the two coats-of-arms - | 0:24:10 | 0:24:13 | |

Edward III alongside the de Bohun's coat-of-arms, | 0:24:13 | 0:24:17 | |

showing their closeness at this stage. | 0:24:17 | 0:24:19 | |

And there's a wonderful scene depicted here, | 0:24:19 | 0:24:22 | |

of King Arthur and Guinevere surrounded by their noblemen, | 0:24:22 | 0:24:26 | |

feasting, holding these golden chalices | 0:24:26 | 0:24:30 | |

and having a really great time. | 0:24:30 | 0:24:32 | |

There there's this very intriguing little scene - | 0:24:32 | 0:24:34 | |

Arthur is obviously dealing with some matters of state. | 0:24:34 | 0:24:37 | |

He's interacting with two characters. | 0:24:37 | 0:24:41 | |

But behind him, Guinevere and Lancelot are in a secret exchange, | 0:24:41 | 0:24:44 | |

they're whispering to one another, | 0:24:44 | 0:24:47 | |

and this is intriguing. | 0:24:47 | 0:24:49 | |

In Arthurian legend, Lancelot's a really important figure, | 0:24:49 | 0:24:53 | |

he's one of the most trusted by King Arthur, | 0:24:53 | 0:24:56 | |

and he's probably most famous for seducing the king's wife, Guinevere. | 0:24:56 | 0:25:01 | |

This eventually brings about the collapse of the Round Table | 0:25:01 | 0:25:04 | |

and the demise of King Arthur. | 0:25:04 | 0:25:06 | |

So, in this character, Lancelot, we see the power struggle | 0:25:06 | 0:25:11 | |

that's constantly taking place between the nobility and the king. | 0:25:11 | 0:25:16 | |

It's interesting that texts like this were so popular | 0:25:16 | 0:25:19 | |

with noble patrons and noble readers, | 0:25:19 | 0:25:22 | |

because it shows how, in texts, the power of the king could be tempered. | 0:25:22 | 0:25:26 | |

But Edward would have a reply to these noble detractors. | 0:25:30 | 0:25:34 | |

One they would not be able to undermine so easily. | 0:25:34 | 0:25:38 | |

In 1348, the homecoming from Edward's triumphant French campaigns | 0:25:42 | 0:25:46 | |

was marked by the usual great feasting and tournaments. | 0:25:46 | 0:25:51 | |

But a far greater menace than war is beginning to sweep Europe - | 0:25:52 | 0:25:57 | |

the Black Death. | 0:25:57 | 0:25:59 | |

By the next year, it's raging in London | 0:26:02 | 0:26:05 | |

and claiming one life in three. | 0:26:05 | 0:26:07 | |

The chronicles tell of licentious behaviour at court | 0:26:08 | 0:26:12 | |

and, through them, we can guess | 0:26:12 | 0:26:14 | |

an apocalyptic and deeply frightened mood. | 0:26:14 | 0:26:17 | |

People think they are going to die. | 0:26:19 | 0:26:22 | |

The Day of Judgment has arrived. | 0:26:23 | 0:26:25 | |

What's notable is that despite this great terror, | 0:26:29 | 0:26:32 | |

there are no references to the plague | 0:26:32 | 0:26:34 | |

in the Royal manuscripts at the time. | 0:26:34 | 0:26:37 | |

It seems that the court would only see what it wants to see | 0:26:37 | 0:26:40 | |

and what it wants to be seen. | 0:26:40 | 0:26:42 | |

What we do know is that in April 1349, | 0:26:42 | 0:26:45 | |

here in the grounds of Windsor Castle, | 0:26:45 | 0:26:48 | |

Edward III organised a great tournament, | 0:26:48 | 0:26:52 | |

while, just ten miles away over there, | 0:26:52 | 0:26:54 | |

London was a charnel house overflowing with the dead. | 0:26:54 | 0:26:58 | |

And over there, in St George's Chapel, | 0:26:58 | 0:27:01 | |

on April 23rd, St George's Day, | 0:27:01 | 0:27:04 | |

he formulates a new chivalric order, the Order of the Garter. | 0:27:04 | 0:27:09 | |

Wow. | 0:27:22 | 0:27:24 | |

Following the example of the Round Table, | 0:27:29 | 0:27:32 | |

there are 25 members in addition to the king. | 0:27:32 | 0:27:34 | |

They are nearly all knights that Edward fought with at Crecy. | 0:27:36 | 0:27:40 | |

What's going on here? | 0:27:40 | 0:27:41 | |

To get a clue, here's Edward III in William Bruges' Garter Book, | 0:27:45 | 0:27:49 | |

written some 90 years later. | 0:27:49 | 0:27:51 | |

Over these pages are all his knights - his brothers-in-arms. | 0:27:51 | 0:27:56 | |

But there's something new here too. | 0:27:56 | 0:27:59 | |

Here is a king invested with almost religious authority. | 0:28:01 | 0:28:05 | |

His favourite saint, the warrior saint, St George, | 0:28:05 | 0:28:08 | |

has been appropriated into the majesty of monarchy. | 0:28:08 | 0:28:14 | |

The king is crowned, standing resplendent, dressed in a tunic | 0:28:14 | 0:28:18 | |

composed of the Arms of England quartered with France. | 0:28:18 | 0:28:22 | |

He wears a cloak emblazoned with the cross of St George, | 0:28:22 | 0:28:27 | |

within the new Garter symbol and motto. | 0:28:27 | 0:28:29 | |

At a single stroke, the monarchy has been sanctified, | 0:28:31 | 0:28:35 | |

purified and strengthened. | 0:28:35 | 0:28:37 | |

It's an incredibly powerful piece of propaganda. | 0:28:37 | 0:28:40 | |

In one of the worst catastrophes England's ever faced, | 0:28:40 | 0:28:43 | |

Edward seems to be saying, "It's business as usual. | 0:28:43 | 0:28:46 | |

"I'm in command and I'm not frightened." | 0:28:46 | 0:28:50 | |

To this day, the coats-of-arms of the original 25 knights, | 0:28:54 | 0:28:58 | |

and those of their successors, | 0:28:58 | 0:29:00 | |

are pinned to the back wall of the chapel stalls. | 0:29:00 | 0:29:03 | |

And the motto to the Order of the Garter's really enigmatic, too. | 0:29:14 | 0:29:18 | |

"Honi soit qui mal y pense". | 0:29:18 | 0:29:19 | |

I believe it relates to Edward's claim to the throne of France. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:26 | |

"Honi soit qui mal y pense" - "Shame on him who thinks evil of it". | 0:29:26 | 0:29:32 | |

The Garter itself is supposed to have been a small leather strap | 0:29:34 | 0:29:38 | |

used to join armour by the knights at Crecy. | 0:29:38 | 0:29:41 | |

Edward III would reserve membership only for those nobles | 0:29:46 | 0:29:50 | |

with the highest records of loyalty and military prowess. | 0:29:50 | 0:29:53 | |

Rather than the mythical figure of Arthur | 0:29:55 | 0:29:59 | |

and his Knights of the Round Table, this represents so much more. | 0:29:59 | 0:30:02 | |

It's like Edward's saying, "I represent religious integrity. | 0:30:02 | 0:30:07 | |

"My kingship is all about down-the-line Christian orthodoxy." | 0:30:07 | 0:30:12 | |

In a masterstroke of image-making, | 0:30:13 | 0:30:17 | |

Edward has bolstered his position as sanctified monarch, | 0:30:17 | 0:30:20 | |

secularised his own saint, and last but not least, | 0:30:20 | 0:30:23 | |

consolidated his power over the nobles. | 0:30:23 | 0:30:26 | |

The king's stamp of authority wasn't just seen in his own propaganda, | 0:30:49 | 0:30:53 | |

but also in the work of his humbler subjects too. | 0:30:53 | 0:30:57 | |

This is an encyclopaedia. | 0:31:16 | 0:31:19 | |

It's not the first encyclopaedia, | 0:31:19 | 0:31:20 | |

but it is the first that's arranged alphabetically. | 0:31:20 | 0:31:24 | |

It was written by a clerk to King Edward III. | 0:31:24 | 0:31:28 | |

It has the delightful name Omne Bonum - "All Good Things". | 0:31:31 | 0:31:35 | |

It has over 1,350 entries and it's illuminated throughout | 0:31:35 | 0:31:42 | |

with these images to illustrate the pieces that they accompany. | 0:31:42 | 0:31:47 | |

It's the huge amount of effort required to order | 0:31:48 | 0:31:51 | |

all these gobbets of good information | 0:31:51 | 0:31:54 | |

that I find so interesting. | 0:31:54 | 0:31:55 | |

So here we've got "Anetum", that's dill. | 0:31:55 | 0:31:59 | |

And this figure is holding up an image of dill. | 0:31:59 | 0:32:02 | |

And here, "Ancipiter", that's a bird of prey, so you can see | 0:32:02 | 0:32:06 | |

this wonderful illumination of the character holding up the bird. | 0:32:06 | 0:32:10 | |

And if we look at this entry for "Anglia", England, | 0:32:14 | 0:32:18 | |

we haven't got a map of the country, instead we've got an image of a king | 0:32:18 | 0:32:23 | |

in all his regalia. | 0:32:23 | 0:32:26 | |

Like king and saint, king and country are now inseparable. | 0:32:27 | 0:32:32 | |

Edward III has clearly done his job well. | 0:32:34 | 0:32:37 | |

These images are really showing us | 0:32:41 | 0:32:43 | |

that mankind is at the centre of everything, | 0:32:43 | 0:32:46 | |

everything is made for his use, | 0:32:46 | 0:32:48 | |

and he's at the very heart of God's creation. | 0:32:48 | 0:32:52 | |

What is also happening with Omne Bonum | 0:33:16 | 0:33:19 | |

is the secularisation of production. | 0:33:19 | 0:33:22 | |

Manuscripts are now not just the preserve | 0:33:22 | 0:33:24 | |

of royalty or religious houses. | 0:33:24 | 0:33:27 | |

Neither of these can now control the thirst for new knowledge. | 0:33:27 | 0:33:31 | |

Soon, the floodgates will be open. | 0:33:31 | 0:33:33 | |

Knowing Edward's enquiring mind, | 0:33:42 | 0:33:44 | |

there's every possibility that he saw Omne Bonum being written. | 0:33:44 | 0:33:48 | |

But what would have interested him much more | 0:33:48 | 0:33:51 | |

would have been the manuscript output from a noble family | 0:33:51 | 0:33:54 | |

that were among the greatest at court. | 0:33:54 | 0:33:57 | |

This great mound is all that now remains of one of the largest | 0:33:59 | 0:34:03 | |

and most important castles in medieval England. | 0:34:03 | 0:34:07 | |

Today, not a stone remains, but in the late 14th century | 0:34:07 | 0:34:11 | |

it was the seat of the de Bohun family, | 0:34:11 | 0:34:13 | |

one of the most powerful noble families in the land. | 0:34:13 | 0:34:16 | |

But late on in Edward III's reign, their lands were broken up. | 0:34:16 | 0:34:20 | |

I believe the Royal Manuscript Collection | 0:34:20 | 0:34:22 | |

holds the key to the mystery of what happened. | 0:34:22 | 0:34:24 | |

Within the walls of Pleshey Castle, | 0:34:26 | 0:34:28 | |

the family had a brilliant little manuscript factory, | 0:34:28 | 0:34:32 | |

employing scribes from the local monastery and so far as we know, | 0:34:32 | 0:34:36 | |

secular artists. | 0:34:36 | 0:34:38 | |

They would be continuously engaged in the painstaking task | 0:34:39 | 0:34:43 | |

of creating at least a dozen stunning manuscripts, | 0:34:43 | 0:34:47 | |

known to have come from Pleshey. | 0:34:47 | 0:34:49 | |

The de Bohun artists could spend years and years | 0:34:52 | 0:34:55 | |

on a single manuscript. | 0:34:55 | 0:34:57 | |

But the length of time an illumination would take to complete | 0:34:57 | 0:35:00 | |

was defined by the availability not just of the artists, | 0:35:00 | 0:35:05 | |

but the supply of its crucial ingredient - gold. | 0:35:05 | 0:35:09 | |

SHE BREATHES OUT HEAVILY | 0:35:13 | 0:35:15 | |

Patricia Lovett is one of only a handful of illuminators | 0:35:17 | 0:35:21 | |

who practise in a way virtually unchanged since medieval times. | 0:35:21 | 0:35:26 | |

Patricia, can you tell me a bit more about the illumination process? | 0:35:26 | 0:35:29 | |

First, the design has to be worked out very precisely. | 0:35:29 | 0:35:32 | |

it's not like watercolour or oil painting, | 0:35:32 | 0:35:37 | |

where you've got leeway and you can change things. | 0:35:37 | 0:35:40 | |

It's a very, very carefully thought-out procedure, | 0:35:40 | 0:35:43 | |

because you need to know exactly where the gold is going to go | 0:35:43 | 0:35:46 | |

before you even start, there's no changing once you've started. | 0:35:46 | 0:35:50 | |

And once the design has been transferred on to vellum, | 0:35:50 | 0:35:55 | |

then this pink compound is laid, | 0:35:55 | 0:35:57 | |

and this is gesso, a mixture of plaster of Paris and various glues. | 0:35:57 | 0:36:02 | |

This is laid as a liquid, with a quill, and allowed to dry | 0:36:02 | 0:36:07 | |

everywhere where there is going to be gold. | 0:36:07 | 0:36:09 | |

I'm going to breathe on the gesso | 0:36:09 | 0:36:11 | |

to reactivate the stickiness in the gesso. | 0:36:11 | 0:36:13 | |

Then the gold leaf is applied | 0:36:16 | 0:36:19 | |

and I have three seconds to get that gold to stick. | 0:36:19 | 0:36:23 | |

And now I'm working my burnisher over the gold leaf. | 0:36:23 | 0:36:26 | |

Gold was chosen for the most precious books | 0:36:26 | 0:36:28 | |

because it doesn't tarnish, unlike silver. | 0:36:28 | 0:36:31 | |

So there are all sorts of pluses for having gold in your book. | 0:36:31 | 0:36:34 | |

Not least that it was evidence | 0:36:34 | 0:36:36 | |

that you were a wealthy enough person to afford it. | 0:36:36 | 0:36:38 | |

To me, the thing that really sets the illuminations apart | 0:36:40 | 0:36:42 | |

from simple decoration is this application of gold. | 0:36:42 | 0:36:45 | |

It's almost like alchemy, isn't it? The changing of states. | 0:36:45 | 0:36:48 | |

Absolutely, you've got this pink powdery compound | 0:36:48 | 0:36:52 | |

which suddenly becomes metallic and brilliant and shiny, | 0:36:52 | 0:36:56 | |

and that's so attractive to us as humans. | 0:36:56 | 0:36:58 | |

Then the painting takes place. | 0:36:58 | 0:37:01 | |

If you can see this strip, these are the base colours. | 0:37:01 | 0:37:04 | |

Then the tones and the shades are added, | 0:37:04 | 0:37:08 | |

the white little highlights, very fine lines, and the black outlines. | 0:37:08 | 0:37:12 | |

And that completes it. | 0:37:12 | 0:37:13 | |

So how long would it take for a medieval scribe to execute | 0:37:13 | 0:37:17 | |

something like this? | 0:37:17 | 0:37:19 | |

This one took about a week. | 0:37:19 | 0:37:21 | |

It's amazing, all the effort that's gone into these | 0:37:21 | 0:37:23 | |

and so many of the artists, their names are lost. They're anonymous. | 0:37:23 | 0:37:28 | |

It wasn't the practice at the time to record who did the writing | 0:37:28 | 0:37:31 | |

and who did the painting. | 0:37:31 | 0:37:33 | |

We do have some names, | 0:37:33 | 0:37:35 | |

but there are some wonderful little notes at the backs of books | 0:37:35 | 0:37:39 | |

where a scribe wrote that he had done it, when and for whom. | 0:37:39 | 0:37:42 | |

And some of them are, "Thank goodness this is finished, | 0:37:42 | 0:37:45 | |

"now get me a drink, | 0:37:45 | 0:37:47 | |

"this was the most boring text I've ever had to write out in my life." | 0:37:47 | 0:37:51 | |

Sometime in the 1370s, the busy manuscript factory | 0:38:10 | 0:38:13 | |

at Pleshey Castle produced this Book of Hours. | 0:38:13 | 0:38:17 | |

Books of hours were small, portable manuscripts | 0:38:21 | 0:38:25 | |

designed to guide the individual through the prayers of the day. | 0:38:25 | 0:38:29 | |

They often contained scenes of moral instruction | 0:38:29 | 0:38:32 | |

derived from Biblical history. | 0:38:32 | 0:38:35 | |

But the de Bohun Hours may tell a different story - | 0:38:35 | 0:38:39 | |

about the demise of this most illustrious family. | 0:38:39 | 0:38:43 | |

The de Bohun family have chosen a fidelity story | 0:38:44 | 0:38:46 | |

from the First Book of Kings. | 0:38:46 | 0:38:49 | |

In it, the future King David is a fugitive, | 0:38:51 | 0:38:55 | |

but he proves his loyalty to a power-mad King Saul | 0:38:55 | 0:38:59 | |

by not killing him when he had the chance. | 0:38:59 | 0:39:01 | |

The first picture shows Saul entering the cave at Ein Gedi | 0:39:01 | 0:39:06 | |

in pursuit of David. | 0:39:06 | 0:39:08 | |

The second shows David cutting off the end of Saul's garment | 0:39:08 | 0:39:13 | |

as he relieves himself. | 0:39:13 | 0:39:15 | |

Then we see David showing the garment to Saul. | 0:39:15 | 0:39:18 | |

And finally, swearing allegiance to him. | 0:39:18 | 0:39:21 | |

This is an image of loyalty, | 0:39:24 | 0:39:26 | |

in which the earl assumes the David persona in order to stress | 0:39:26 | 0:39:30 | |

the faithfulness of the de Bohuns to the crown. | 0:39:30 | 0:39:34 | |

But this Biblical account may mask a terrible end to the family. | 0:39:34 | 0:39:38 | |

There's a story that Sir Humphrey, the last of the de Bohun earls, | 0:39:40 | 0:39:44 | |

was suspected of poisoning fellow Garter knight the Earl of Warwick | 0:39:44 | 0:39:49 | |

in one of Edward's French campaigns in 1371. | 0:39:49 | 0:39:52 | |

From that time, he seems to have been out of favour with the king. | 0:39:54 | 0:39:58 | |

One of the richest men in the land, | 0:39:59 | 0:40:01 | |

Humphrey is now vulnerable and his estates, a target. | 0:40:01 | 0:40:07 | |

Rumour has it that Edward III had Humphrey secretly hanged in 1373. | 0:40:10 | 0:40:15 | |

It's no coincidence that both his lands and his books | 0:40:15 | 0:40:18 | |

were then shared between the king's son and grandson | 0:40:18 | 0:40:23 | |

on their respective weddings to Humphrey's two young daughters. | 0:40:23 | 0:40:27 | |

The destruction of the de Bohun dynasty | 0:40:31 | 0:40:34 | |

may show Edward's ruthlessness in disposing of a noble, | 0:40:34 | 0:40:37 | |

however loyal, with such a prize at stake. | 0:40:37 | 0:40:40 | |

But that's not the end of the story. | 0:40:42 | 0:40:44 | |

Humphrey's younger daughter, Mary, | 0:40:44 | 0:40:46 | |

who was dragged from a convent into marriage, | 0:40:46 | 0:40:49 | |

was to be the mother of England's great warrior king, Henry V. | 0:40:49 | 0:40:54 | |

What Henry would do would eclipse everything | 0:40:56 | 0:40:59 | |

his great-grandfather Edward III had done, | 0:40:59 | 0:41:02 | |

and HIS strategy is clear from the start. | 0:41:02 | 0:41:05 | |

"High and noble prince excellent, | 0:41:08 | 0:41:12 | |

"my lord, the prince, oh, lord gracious, | 0:41:12 | 0:41:16 | |

"I humble servant and obedient unto your estate high and glorious." | 0:41:16 | 0:41:21 | |

Gosh, this is one of the most obsequious introductions | 0:41:21 | 0:41:24 | |

I've ever read to a manuscript. | 0:41:24 | 0:41:25 | |

The year is 1410 and the young Prince of Wales, | 0:41:25 | 0:41:29 | |

soon to be the great Henry V, | 0:41:29 | 0:41:30 | |

is standing in for his father, Henry IV, who was ill. | 0:41:30 | 0:41:36 | |

Thomas Hoccleve is a court clerk and a poet | 0:41:36 | 0:41:41 | |

and has written this for the future king. | 0:41:41 | 0:41:43 | |

It's called the Regement of Princes, | 0:41:43 | 0:41:45 | |

and it's a manual of instruction for the king-in-waiting. | 0:41:45 | 0:41:49 | |

Like the Secretum Secretorum before it, | 0:41:49 | 0:41:53 | |

it urges the king to rule according to the cardinal virtues - | 0:41:53 | 0:41:57 | |

justice, prudence, wisdom and mercy. | 0:41:57 | 0:42:01 | |

But it's all written in English. | 0:42:01 | 0:42:05 | |

Look here in the margins. There's an image here of Geoffrey Chaucer. | 0:42:05 | 0:42:09 | |

Chaucer was Hoccleve's inspiration and he actually says in the text | 0:42:09 | 0:42:14 | |

that Chaucer was "the first finder of our fair language". | 0:42:14 | 0:42:18 | |

For me, this is another stage in the break with France | 0:42:22 | 0:42:25 | |

and the forging of England's identity as a separate nation. | 0:42:25 | 0:42:29 | |

It's the use of English that's absolutely key | 0:42:30 | 0:42:33 | |

to understanding the significance of this manuscript. | 0:42:33 | 0:42:36 | |

By using English, | 0:42:36 | 0:42:38 | |

Hoccleve is stressing the Englishness of the Prince of Wales. | 0:42:38 | 0:42:42 | |

For the first time in three-and-a-half centuries, | 0:42:42 | 0:42:44 | |

we have a claimant to the throne | 0:42:44 | 0:42:46 | |

who has all four English-born grandparents. | 0:42:46 | 0:42:49 | |

Henry V will use his Englishness | 0:42:53 | 0:42:55 | |

as a rallying cry in a violent and explosive assertion | 0:42:55 | 0:42:59 | |

of England's long-standing claims to the French crown. | 0:42:59 | 0:43:03 | |

In 1415, the great victory at the Battle of Agincourt | 0:43:06 | 0:43:11 | |

paved the way for the English occupation of half of France. | 0:43:11 | 0:43:16 | |

By 1420, Henry V's armies are at the gates of Paris, | 0:43:16 | 0:43:21 | |

and he forces the French king to hand over the succession. | 0:43:21 | 0:43:26 | |

But Henry delivers an even greater blow, when the French royal palace, | 0:43:26 | 0:43:30 | |

the Louvre, and its treasures, including its library, | 0:43:30 | 0:43:34 | |

falls into the hands of the king's brother, John, Duke of Bedford. | 0:43:34 | 0:43:39 | |

So, in the 1420s, some of Europe's most valuable objects | 0:43:41 | 0:43:46 | |

cross these waters into the hands of the upstart nation. | 0:43:46 | 0:43:50 | |

This is a very good example of the high quality deluxe book | 0:44:02 | 0:44:08 | |

that the English were getting access to | 0:44:08 | 0:44:11 | |

by their being in charge in France. | 0:44:11 | 0:44:14 | |

Every single page has these gold borders, | 0:44:14 | 0:44:18 | |

and then it also has these magnificent illustrations | 0:44:18 | 0:44:21 | |

which are by some of the best artists of the time. | 0:44:21 | 0:44:24 | |

This is the top-end, | 0:44:24 | 0:44:27 | |

this is as good as you will ever get in a book of this nature. | 0:44:27 | 0:44:33 | |

There's as much gold on this page as you could possibly get on it. | 0:44:33 | 0:44:37 | |

Here, we have one of the most magnificent images in the book... | 0:44:45 | 0:44:49 | |

Oh, gosh, yeah, that's not an understatement! Look at the detail! | 0:44:49 | 0:44:54 | |

A wonderful depiction of the Virgin and Child, | 0:44:54 | 0:44:58 | |

with these beautiful angels, and then you've got the saint | 0:44:58 | 0:45:03 | |

presenting this young prince to the Virgin, | 0:45:03 | 0:45:06 | |

and then this banderol joining them, | 0:45:06 | 0:45:08 | |

this is their conversation, their sacred conversation that's going on. | 0:45:08 | 0:45:13 | |

God, it's heart-stopping, the background is absolutely exquisite. | 0:45:13 | 0:45:19 | |

Yeah, so you have this frame of sparkling gold | 0:45:19 | 0:45:23 | |

and imagine that with candlelight flickering | 0:45:23 | 0:45:26 | |

and catching the gold in different ways. | 0:45:26 | 0:45:29 | |

So it clearly looks royal. Who was it intended for? | 0:45:29 | 0:45:34 | |

Well, this little figure here is a young prince, | 0:45:34 | 0:45:37 | |

with the Arms of England and France ancient. | 0:45:37 | 0:45:42 | |

So it looks like an English prince, | 0:45:42 | 0:45:44 | |

but actually it started as a French prince. | 0:45:44 | 0:45:48 | |

What has happened is | 0:45:48 | 0:45:50 | |

that the artist has intruded over the repeated Fleur de Lys, | 0:45:50 | 0:45:56 | |

the Arms of England. | 0:45:56 | 0:45:58 | |

And so, this French prince has become an English prince. | 0:45:58 | 0:46:03 | |

The young prince is actually an infant, the future Henry VI. | 0:46:04 | 0:46:08 | |

Henry V has died in 1422, leaving his brother, John, Duke of Bedford, | 0:46:10 | 0:46:16 | |

to safeguard the education of a boy who would role both kingdoms. | 0:46:16 | 0:46:20 | |

The book was made for someone that's around eight, nine-years-old, | 0:46:20 | 0:46:25 | |

and then it is transferred to someone around the same age as this. | 0:46:25 | 0:46:29 | |

When we think that young aristocrats engaged with the psalms. | 0:46:29 | 0:46:33 | |

And it's also very relevant as well that it's the psalms, | 0:46:33 | 0:46:36 | |

because it's coming from King David, | 0:46:36 | 0:46:39 | |

there's this kingly authority all the way through this text. | 0:46:39 | 0:46:43 | |

Yes, well, if we turn to the beginning of the book, there he is. | 0:46:43 | 0:46:47 | |

-There's the singer of the psalms, as a king. -As a king, yeah. | 0:46:47 | 0:46:52 | |

But then, above, you've got a thing that might have been more attractive | 0:46:52 | 0:46:56 | |

to an eight or nine-year-old, | 0:46:56 | 0:46:58 | |

which is this fight that's going on up at the top, | 0:46:58 | 0:47:02 | |

between David, who's really going to whack Goliath, who's facing him. | 0:47:02 | 0:47:08 | |

-It would appeal to a boy! -I think so! I think it really would. | 0:47:08 | 0:47:12 | |

In terms of the skill and the artistry of this, | 0:47:12 | 0:47:15 | |

it seems far and away better than anything I've seen | 0:47:15 | 0:47:18 | |

coming out of England at this point. | 0:47:18 | 0:47:20 | |

It's unbeatable, it's just haute couture of its time, isn't it? | 0:47:20 | 0:47:24 | |

The colours, the naturalism, just the sheer beauty of the page. | 0:47:24 | 0:47:29 | |

France has the full ascendancy at this period and beyond. | 0:47:29 | 0:47:33 | |

It's wonderful to think about these books as treasures as well. | 0:47:33 | 0:47:38 | |

That they are the treasures of a realm. | 0:47:38 | 0:47:40 | |

By John, Duke of Bedford taking the library books, | 0:47:40 | 0:47:43 | |

-he's taking the treasure of that... -He's very much taking the treasures, | 0:47:43 | 0:47:48 | |

and the one saving grace is that unlike the plate and the metalwork, | 0:47:48 | 0:47:54 | |

which could be boiled down when you ran short of cash, | 0:47:54 | 0:47:59 | |

the manuscripts couldn't, so they've come through as... | 0:47:59 | 0:48:02 | |

They were the same level of treasure, but you couldn't melt them down. | 0:48:02 | 0:48:08 | |

By the time he was nine, | 0:48:13 | 0:48:15 | |

the young Prince Henry would be reading and absorbing | 0:48:15 | 0:48:18 | |

one of the great masterpieces of medieval literature. | 0:48:18 | 0:48:21 | |

Nothing reflects more England's expectations | 0:48:23 | 0:48:26 | |

at the forthcoming coronation of Henry as King of France | 0:48:26 | 0:48:29 | |

than the famous Bedford Hours. | 0:48:29 | 0:48:31 | |

Oh, this is a moment for me! | 0:48:38 | 0:48:41 | |

Wow! | 0:48:41 | 0:48:42 | |

Oh gosh, right, I'm entering into the Bedford Hours. | 0:48:46 | 0:48:52 | |

It was given to the young king | 0:49:06 | 0:49:08 | |

by his aunt, Anne of Burgundy, and his uncle, John of Bedford, | 0:49:08 | 0:49:12 | |

and he received it on Christmas Eve, 1430, | 0:49:12 | 0:49:16 | |

this is just a year before his coronation as King of France. | 0:49:16 | 0:49:21 | |

This is the culmination of 80 years of English foreign policy, | 0:49:21 | 0:49:25 | |

and a hugely important event | 0:49:25 | 0:49:28 | |

that's just preceded by the gift of this manuscript. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:31 | |

The Duke of Bedford has again adapted a manuscript probably | 0:49:33 | 0:49:37 | |

intended for a French prince. | 0:49:37 | 0:49:39 | |

But the unknown artist has, from his Paris workshop, | 0:49:40 | 0:49:44 | |

created some of the most outstanding images of the age. | 0:49:44 | 0:49:49 | |

A remarkable sequence of full-page illuminations, | 0:49:49 | 0:49:53 | |

depicting scenes from the Book of Genesis. | 0:49:53 | 0:49:56 | |

They show the creation by an all-seeing God. | 0:50:06 | 0:50:09 | |

The birth of Eve from Adam. | 0:50:11 | 0:50:15 | |

Noah and the flood. | 0:50:17 | 0:50:19 | |

This, for me, in terms of its artistry, its skill, | 0:50:21 | 0:50:24 | |

it's a work of art. | 0:50:24 | 0:50:26 | |

And here's the creation of languages in the Tower of Babel. | 0:50:35 | 0:50:39 | |

These Biblical scenes are all scenarios | 0:50:39 | 0:50:42 | |

that a young Christian prince should know. | 0:50:42 | 0:50:45 | |

At great expense, the education of the young Henry continues. | 0:50:46 | 0:50:51 | |

If you look here, we have a portrait of the Duke himself, | 0:50:56 | 0:51:00 | |

kneeling before St George, | 0:51:00 | 0:51:02 | |

complete with an English flag emblazoned on his chest. | 0:51:02 | 0:51:06 | |

This is significant, | 0:51:06 | 0:51:07 | |

at this point England has conquered France, | 0:51:07 | 0:51:10 | |

so who better for John to be kneeling in front of | 0:51:10 | 0:51:14 | |

than the warrior saint of England? | 0:51:14 | 0:51:16 | |

The book also celebrates the marriage of Duke John | 0:51:18 | 0:51:22 | |

to Anne of Burgundy in 1423, | 0:51:22 | 0:51:24 | |

an alliance designed to protect the new dual monarchy. | 0:51:24 | 0:51:28 | |

Really, for the first time, | 0:51:28 | 0:51:32 | |

images of real people are becoming individual and recognisable. | 0:51:32 | 0:51:36 | |

The medieval framework of symbolism is beginning to take a back seat. | 0:51:36 | 0:51:41 | |

Whilst the treatment of the saint and the Duke inside the window | 0:51:42 | 0:51:46 | |

of the picture is modern and realistic, | 0:51:46 | 0:51:49 | |

the images of the sufferings of the saint | 0:51:49 | 0:51:52 | |

in the margins are still symbolic and medieval. | 0:51:52 | 0:51:55 | |

This is such a powerful present. | 0:51:57 | 0:52:00 | |

The Bedford Hours is more than just a prayer book, | 0:52:00 | 0:52:04 | |

it's bursting with status | 0:52:04 | 0:52:06 | |

and encapsulates the aspirations of an entire nation. | 0:52:06 | 0:52:11 | |

On his coming of age in 1437, | 0:52:13 | 0:52:16 | |

England's nobility hoped King Henry VI would do everything possible | 0:52:16 | 0:52:20 | |

to protect his dual inheritance on the battlefields of France | 0:52:20 | 0:52:25 | |

against resurgent French armies. | 0:52:25 | 0:52:27 | |

But Henry never goes to fight the war in France. | 0:52:29 | 0:52:32 | |

I'm with the historian John Watts to find out why. | 0:52:39 | 0:52:42 | |

So John, what do we know about Henry VI? | 0:52:44 | 0:52:47 | |

Henry VI comes to the throne at nine-months-old. | 0:52:47 | 0:52:49 | |

There's then a period of royal minority | 0:52:49 | 0:52:51 | |

where the realm is governed by a council. | 0:52:51 | 0:52:53 | |

The councillors wait eagerly for the king to take over, | 0:52:53 | 0:52:56 | |

but he shows no initiative, and they find themselves | 0:52:56 | 0:52:58 | |

having to hand authority to him, which he doesn't exercise. | 0:52:58 | 0:53:02 | |

So it's hard to know exactly what kind of a person Henry is, | 0:53:02 | 0:53:05 | |

whether he was a pious figure, | 0:53:05 | 0:53:07 | |

as positive legend suggests, or whether he was simply an idiot, | 0:53:07 | 0:53:11 | |

as a more negative views of his subjects tend to imply. | 0:53:11 | 0:53:16 | |

The king has to be an active and effective individual, | 0:53:16 | 0:53:21 | |

and what people don't realise is there's good blueprints for kingship | 0:53:21 | 0:53:25 | |

available in this time. | 0:53:25 | 0:53:26 | |

Advice-writers like Hoccleve, in his Regement of Princes, | 0:53:26 | 0:53:30 | |

are telling kings how to govern, | 0:53:30 | 0:53:33 | |

and central to Hoccleve's theory | 0:53:33 | 0:53:35 | |

is an idea of the four cardinal virtues - | 0:53:35 | 0:53:37 | |

so the king must be just, he must be prudent, | 0:53:37 | 0:53:41 | |

he must be wise, and he must show mercy. | 0:53:41 | 0:53:44 | |

And he must hear the advice of his councillors | 0:53:44 | 0:53:47 | |

and then take a decision and authorise that decision fully. | 0:53:47 | 0:53:51 | |

That's the blueprint for kingship, that's all a king needs to do. | 0:53:51 | 0:53:55 | |

But Henry simply doesn't. | 0:53:55 | 0:53:56 | |

He doesn't show the constancy that's involved in fortitude. | 0:53:56 | 0:54:01 | |

He isn't determined to do justice. | 0:54:01 | 0:54:03 | |

He won't fight to defend his rights or his realm. | 0:54:03 | 0:54:07 | |

Because he won't go to France - | 0:54:07 | 0:54:08 | |

and he's the only king in this period who doesn't fight in France - | 0:54:08 | 0:54:13 | |

nobody is willing to go and the English conquest unravels. | 0:54:13 | 0:54:18 | |

The medieval mind would understand the wheel of fortune. | 0:54:20 | 0:54:24 | |

But in throwing it all away, Henry exceeded the expectations | 0:54:24 | 0:54:28 | |

of even the most pessimistic of his nobles. | 0:54:28 | 0:54:31 | |

The king turned out to be one of the worst kings England had ever had. | 0:54:36 | 0:54:41 | |

In 1444, at a time his armies are losing in France, | 0:54:45 | 0:54:51 | |

Henry's bride-to-be, Margaret of Anjou, | 0:54:51 | 0:54:54 | |

was given an extraordinary wedding present. | 0:54:54 | 0:54:58 | |

This magnificent manuscript is the Shrewsbury Book. | 0:54:58 | 0:55:02 | |

It was made by the gentleman depicted here, Sir John Talbot, | 0:55:02 | 0:55:05 | |

he's the commander of the English troops in France, | 0:55:05 | 0:55:11 | |

and beside him is his symbol, the Talbot dog, that's now extinct. | 0:55:11 | 0:55:16 | |

He's handing this book over to Margaret of Anjou, | 0:55:16 | 0:55:20 | |

and this is designed as a wedding gift for her, | 0:55:20 | 0:55:24 | |

because she's going to marry King Henry VI. | 0:55:24 | 0:55:26 | |

But just opposite is what must be one of the most intricately | 0:55:26 | 0:55:31 | |

and elaborately decorated pages of any book ever written. | 0:55:31 | 0:55:36 | |

It's a powerful image that sets out | 0:55:38 | 0:55:40 | |

all Henry's claims to the French throne. | 0:55:40 | 0:55:44 | |

On the left-hand side is the long line of French monarchs. | 0:55:44 | 0:55:48 | |

And on the right, there's the genealogy of the English kings. | 0:55:53 | 0:55:57 | |

They join at the bottom, where Henry sits guarded by angels | 0:55:57 | 0:56:01 | |

and the insignia of the Garter. | 0:56:01 | 0:56:04 | |

And the whole edifice is propped up by Henry's guardians in chief - | 0:56:04 | 0:56:09 | |

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and Richard, Duke of York. | 0:56:09 | 0:56:14 | |

And both royal dynasties are given a common ancestor - | 0:56:17 | 0:56:22 | |

St Louis, the 13th-century saint-king of France. | 0:56:22 | 0:56:25 | |

If ever there was a solid vision of the right of succession, this is it. | 0:56:27 | 0:56:32 | |

All the kings we've seen over the last 120 years are here - | 0:56:32 | 0:56:37 | |

Henry V, the warrior king, the great Edward III, | 0:56:37 | 0:56:42 | |

and even the tumbledown king, Edward II, has been restored to majesty. | 0:56:42 | 0:56:48 | |

But never was one man's fortune more wasted. | 0:56:50 | 0:56:55 | |

Behind this elaborate and somewhat optimistic fantasy | 0:56:55 | 0:56:59 | |

was a stark reality, that there was not a strong English king. | 0:56:59 | 0:57:04 | |

Even as the book was being written, the French, | 0:57:04 | 0:57:08 | |

united under the inspiration of their own champion, Joan of Arc, | 0:57:08 | 0:57:12 | |

were reclaiming English lands. | 0:57:12 | 0:57:14 | |

One by one, the remaining English dominions begin to disappear. | 0:57:18 | 0:57:23 | |

Normandy is lost by 1450, followed by Gascony three years later, | 0:57:23 | 0:57:29 | |

when the English project in France dies for ever. | 0:57:29 | 0:57:32 | |

I think that what all these manuscripts are telling us | 0:57:35 | 0:57:38 | |

is that in an ever-expanding | 0:57:38 | 0:57:41 | |

and ever more complex and literary world, | 0:57:41 | 0:57:44 | |

the institution of medieval kingship must constantly reinvent itself. | 0:57:44 | 0:57:50 | |

Power hinges on the strength and personality of the king, | 0:57:50 | 0:57:54 | |

and his ability to manipulate his noblemen through propaganda. | 0:57:54 | 0:57:59 | |

And the manuscripts themselves are changing. | 0:57:59 | 0:58:02 | |

On the dawn of printing, as books are becoming more commonplace, | 0:58:02 | 0:58:06 | |

manuscripts commissioned by and for the royalty are characterised | 0:58:06 | 0:58:10 | |

by being all the more elaborate and exquisite. | 0:58:10 | 0:58:14 | |

Royalty is now defined as much by its majesty as by its divinity. | 0:58:14 | 0:58:19 | |

Next time - the final flowering of illuminated manuscripts, | 0:58:23 | 0:58:27 | |

as the Tudors take over England and its church. | 0:58:27 | 0:58:33 | |

Subtitles by Evelyn Morrish, Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:58:39 | 0:58:42 | |

E-mail [email protected] | 0:58:42 | 0:58:45 |