Libraries Gave Us Power Illuminations: The Private Lives of Medieval Kings

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Libraries Gave Us Power. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Some 700 years ago, at the Tower of London, | 0:00:06 | 0:00:10 | |

amidst the usual screams of terror, you might have heard | 0:00:10 | 0:00:14 | |

the sighs of an amorous Frenchman. | 0:00:14 | 0:00:16 | |

Charles, Duke of Orleans, had been captured in battle at Agincourt. | 0:00:18 | 0:00:23 | |

His 24 years as a prisoner were whiled away writing love poems. | 0:00:23 | 0:00:30 | |

"Strengthen, my love, this castle of my heart, | 0:00:30 | 0:00:33 | |

"And with some store of pleasure, give me aid." | 0:00:33 | 0:00:38 | |

The poems were well known among the European elite of the day. | 0:00:38 | 0:00:42 | |

This edition was hand-made for England's Royal Library | 0:00:42 | 0:00:46 | |

in the 1470s. | 0:00:46 | 0:00:47 | |

What's most interesting is how these French poems | 0:00:50 | 0:00:53 | |

have been presented for an English audience. | 0:00:53 | 0:00:56 | |

'The author is pictured at his "noble" work, | 0:00:57 | 0:01:01 | |

'but step back a little, | 0:01:01 | 0:01:03 | |

'and it's clear he's the captive of English troops. | 0:01:03 | 0:01:06 | |

'He's imprisoned in the dazzling whiteness of the Tower. | 0:01:08 | 0:01:14 | |

'And he's engulfed by the splendour of London. | 0:01:14 | 0:01:17 | |

'This is the very first topographically accurate image | 0:01:18 | 0:01:21 | |

'of the city.' | 0:01:21 | 0:01:23 | |

All this celebrates not the work of a French poet, | 0:01:23 | 0:01:27 | |

but the power of the English nation. | 0:01:27 | 0:01:29 | |

This manuscript is sending out a clear message. | 0:01:29 | 0:01:33 | |

England is once again a force to be reckoned with, | 0:01:33 | 0:01:36 | |

and its kings want to be players on the world stage. | 0:01:36 | 0:01:40 | |

'And their weapon of choice, when competing with European rivals | 0:01:40 | 0:01:44 | |

'to be the most magnificent of monarchs, was the manuscript.' | 0:01:44 | 0:01:48 | |

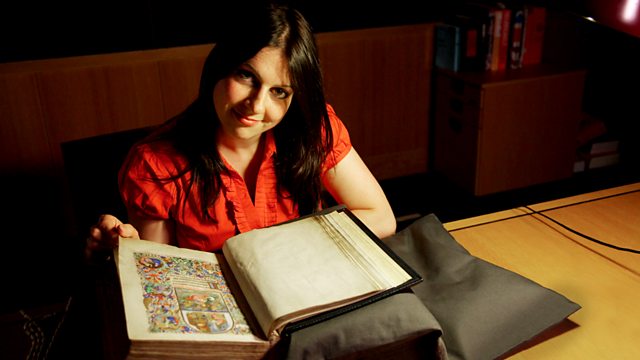

'For this series, | 0:01:52 | 0:01:53 | |

'I've been given unrivalled access to the Crown Jewels of illumination, | 0:01:53 | 0:01:58 | |

'the royal Manuscripts Collection at the British Library. | 0:01:58 | 0:02:02 | |

'Few people have ever seen these miraculous survivors, | 0:02:02 | 0:02:07 | |

'except for the monarchs who owned them. | 0:02:07 | 0:02:10 | |

They were custom made for kings, they were about kings, | 0:02:10 | 0:02:13 | |

and they were read by kings. | 0:02:13 | 0:02:16 | |

'I've been exploring the world which created these manuscripts. | 0:02:16 | 0:02:20 | |

'And going to the places where they were made. | 0:02:24 | 0:02:27 | |

'It's a journey that's taken me from the Anglo Saxons, | 0:02:30 | 0:02:33 | |

'who first united England, | 0:02:33 | 0:02:36 | |

'through centuries of conquest and conflict with France. | 0:02:36 | 0:02:40 | |

'In this episode, the story of the Royal Manuscripts | 0:02:42 | 0:02:46 | |

'draws to its conclusion, | 0:02:46 | 0:02:47 | |

'with the last great flowering of illumination, | 0:02:47 | 0:02:50 | |

'and the role books played for the Tudors. | 0:02:50 | 0:02:54 | |

'I'm on the trail of three kings who led England | 0:02:54 | 0:02:57 | |

'out of the Medieval world and into its Renaissance. | 0:02:57 | 0:03:03 | |

'In 1476, William Caxton began printing in England.' | 0:03:17 | 0:03:22 | |

'One of his patrons was Margaret of York, the sister of King Edward IV.' | 0:03:28 | 0:03:32 | |

'Yet, surprisingly, the arrival of this modern technology | 0:03:44 | 0:03:49 | |

'didn't mean the death of handwritten, hand-painted books. | 0:03:49 | 0:03:53 | |

'In fact, some of the great achievements of the Renaissance | 0:03:56 | 0:04:01 | |

'would take place in a medieval art form, | 0:04:01 | 0:04:04 | |

'which proved remarkably durable.' | 0:04:04 | 0:04:07 | |

Of course, the arrival of cheaper, more easily produced printed books | 0:04:07 | 0:04:11 | |

had an effect on the market for illuminated manuscripts. | 0:04:11 | 0:04:15 | |

These bespoke artworks became even more of a luxury good. | 0:04:15 | 0:04:19 | |

'Now, the illuminator's art was only an option | 0:04:21 | 0:04:24 | |

'for the very wealthiest of elites. | 0:04:24 | 0:04:27 | |

'Chief among them, royalty. | 0:04:27 | 0:04:29 | |

'One of the biggest collectors of all in the late 15th century | 0:04:31 | 0:04:34 | |

'was Edward of York, the King of England. | 0:04:34 | 0:04:37 | |

'And in a highly secure inner sanctum of the British Library, | 0:04:41 | 0:04:45 | |

'the collection which this king built up | 0:04:45 | 0:04:47 | |

'still remains largely intact. | 0:04:47 | 0:04:51 | |

'This is just one of up to 50 books Edward is believed to have had made. | 0:04:57 | 0:05:02 | |

'The first thing that strikes you is the choice of language. | 0:05:02 | 0:05:06 | |

'At a time when books were being printed in English, | 0:05:06 | 0:05:10 | |

'the ruling classes still favoured handwritten French. | 0:05:10 | 0:05:13 | |

'It was the language of the elite, | 0:05:14 | 0:05:16 | |

'as exclusive as the manuscript itself had become.' | 0:05:16 | 0:05:19 | |

Nearly all the manuscripts Edward commissioned | 0:05:23 | 0:05:27 | |

have something in common. They were histories. | 0:05:27 | 0:05:30 | |

'This book's title is Miroir Historial, which is one reason why | 0:05:30 | 0:05:35 | |

'its author, Vincent de Beauvais, is pictured with a looking glass. | 0:05:35 | 0:05:39 | |

'The subject reflects the interests and tastes of its royal reader.' | 0:05:39 | 0:05:44 | |

Edward personally led his army | 0:05:44 | 0:05:46 | |

into some of the most important battles in the War of the Roses. | 0:05:46 | 0:05:50 | |

He was sent away into foreign exile, and he even deposed Henry VI twice. | 0:05:50 | 0:05:56 | |

Edward's life WAS history. | 0:05:56 | 0:05:58 | |

'There's something else which Edward would have identified with here. | 0:05:59 | 0:06:03 | |

'The number of books on display. | 0:06:03 | 0:06:06 | |

'A library has become something to aspire to.' | 0:06:06 | 0:06:11 | |

And of course, Edward IV is building up a collection like this himself, | 0:06:11 | 0:06:16 | |

so this image would have flattered the King, | 0:06:16 | 0:06:18 | |

by implying that he too was a great scholar. | 0:06:18 | 0:06:21 | |

'But scholarship wasn't the King's only motive | 0:06:23 | 0:06:26 | |

'for building his library. | 0:06:26 | 0:06:28 | |

'And that becomes clear when you see the book's original home. | 0:06:28 | 0:06:33 | |

'When first completed, | 0:06:37 | 0:06:38 | |

'they would have been carried in wooden chests across this bridge. | 0:06:38 | 0:06:43 | |

'It led to the King's favourite palace, Eltham, in South London. | 0:06:43 | 0:06:48 | |

'The only Medieval section still to survive was created by Edward, | 0:06:48 | 0:06:53 | |

'and it shows how different he was from his royal predecessor.' | 0:06:53 | 0:06:58 | |

During the chaotic reign of Henry VI, | 0:06:58 | 0:07:00 | |

the Crown lost virtually all its territories in France. | 0:07:00 | 0:07:04 | |

The land was corrupt and lawless, | 0:07:04 | 0:07:06 | |

and the King himself for a time was a raving lunatic. | 0:07:06 | 0:07:10 | |

Edward's mission was to rebuild the reputation of the monarchy. | 0:07:10 | 0:07:14 | |

And to do that, he built this great hall. | 0:07:14 | 0:07:17 | |

'Although the stunning hammerbeam ceiling looks just as it did | 0:07:31 | 0:07:35 | |

'when completed in 1480, | 0:07:35 | 0:07:37 | |

'the walls lack the ornate tapestries which once hung here. | 0:07:37 | 0:07:42 | |

'There's some sense of what they looked like | 0:07:42 | 0:07:45 | |

'in this portrait of Edward, from one of his manuscripts.' | 0:07:45 | 0:07:49 | |

Edward IV is a king with a strong sense of style. | 0:07:52 | 0:07:55 | |

When he has this built, he is creating for himself | 0:07:55 | 0:07:58 | |

a stage at which the spectacle of monarchy will be able to be enacted. | 0:07:58 | 0:08:02 | |

There's a strong sense that this is to do with | 0:08:02 | 0:08:05 | |

the personal image of the King. | 0:08:05 | 0:08:06 | |

How he will appear. | 0:08:06 | 0:08:08 | |

It didn't do him any damage that he was ridiculously good looking and very tall. | 0:08:08 | 0:08:12 | |

But he likes his clothes, he likes his jewellery, | 0:08:12 | 0:08:15 | |

he likes all the trappings. | 0:08:15 | 0:08:17 | |

The sun in splendour is his heraldic insignia, | 0:08:17 | 0:08:20 | |

and it's entirely appropriate. | 0:08:20 | 0:08:21 | |

So, it's the look of a king. He's trying to get the look of a king. | 0:08:21 | 0:08:25 | |

Yes, but I wouldn't suggest there's anything frivolous about that. | 0:08:25 | 0:08:29 | |

The look of a king is a vital part of statecraft. | 0:08:29 | 0:08:31 | |

Remember, he has lived through the Wars of the Roses, | 0:08:31 | 0:08:34 | |

and the disastrous reign of his predecessor Henry VI, | 0:08:34 | 0:08:36 | |

who no-one thought looked like a king. | 0:08:36 | 0:08:38 | |

Henry VI, who, when times got tough, would hide in a monastery. | 0:08:38 | 0:08:42 | |

That isn't Edward IV's style. | 0:08:42 | 0:08:44 | |

He knows that to be a king, you've got to look the part, | 0:08:44 | 0:08:47 | |

and he looks the part. | 0:08:47 | 0:08:48 | |

So, all this lavishness that you've described, | 0:08:48 | 0:08:51 | |

that I can see all around me, comes through in the manuscripts. | 0:08:51 | 0:08:55 | |

All Edward IV's manuscripts are these large tomes. | 0:08:55 | 0:08:59 | |

They're big display books, | 0:08:59 | 0:09:01 | |

and they've got all this colour and amazing intricate detail in them. | 0:09:01 | 0:09:05 | |

And it's just amazing to think about these surroundings, you know, | 0:09:05 | 0:09:09 | |

this magnificent ceiling, the tapestries, | 0:09:09 | 0:09:12 | |

all that jewellery and plate, and then these beautiful bound books | 0:09:12 | 0:09:16 | |

in the midst of all of that. | 0:09:16 | 0:09:17 | |

Yeah, all these things are the props of the monarchy. | 0:09:17 | 0:09:20 | |

And they all have to be here for it to work as well as it did. | 0:09:20 | 0:09:24 | |

'Collecting fine manuscripts posed a particular challenge for Edward. | 0:09:27 | 0:09:33 | |

'England could no longer boast the best illuminators. | 0:09:33 | 0:09:37 | |

'For centuries now, royal manuscripts had been made in France. | 0:09:37 | 0:09:41 | |

'But since Henry VI had lost England's territories | 0:09:41 | 0:09:44 | |

'on the other side of the Channel, Edward had to find another source. | 0:09:44 | 0:09:48 | |

'He turned to the centre for must-have luxury goods at the time. | 0:09:51 | 0:09:56 | |

'Bruges. | 0:09:59 | 0:10:02 | |

'In the late 15th century, the city was part of the Duchy of Burgundy, | 0:10:04 | 0:10:09 | |

'and one of the commercial and artistic powerhouses of Europe. | 0:10:09 | 0:10:13 | |

'The unique qualities of the place had a visible impact | 0:10:15 | 0:10:19 | |

'on the manuscripts produced here. | 0:10:19 | 0:10:21 | |

'Take, for example, this image, from one of Edward's books.' | 0:10:23 | 0:10:27 | |

How do we know it was made here in Bruges? | 0:10:27 | 0:10:30 | |

Well, for starters, there's a handy visual clue. | 0:10:30 | 0:10:33 | |

If you look through the window in the background, you can see | 0:10:33 | 0:10:36 | |

these red brick buildings with crenellated facades | 0:10:36 | 0:10:40 | |

reflected in the water. | 0:10:40 | 0:10:41 | |

And even today, that's what this beautiful medieval city looks like. | 0:10:41 | 0:10:45 | |

'But there's more to the Bruges style | 0:10:48 | 0:10:51 | |

'than a love of local landscape. | 0:10:51 | 0:10:53 | |

'What's most distinctive is the whole approach to painting. | 0:10:53 | 0:10:56 | |

'The picture imagines the book's author, Giovanni Boccaccio, | 0:10:58 | 0:11:03 | |

'meeting Lady Fortune, the personification of chance. | 0:11:03 | 0:11:07 | |

'But this supernatural apparition isn't really | 0:11:07 | 0:11:10 | |

'the centre of attention here. | 0:11:10 | 0:11:13 | |

'In fact, a third character is more interested | 0:11:13 | 0:11:16 | |

'in what's outside the window than a woman with six arms. | 0:11:16 | 0:11:20 | |

'This image anticipates later Dutch painters such as Vermeer, | 0:11:20 | 0:11:24 | |

'because its real subject is the natural textures of reality. | 0:11:24 | 0:11:28 | |

'It's all about the play of light and shade, | 0:11:28 | 0:11:32 | |

'the perspective of the room, the quality of the landscape.' | 0:11:32 | 0:11:36 | |

It's the realism of the images made here in Bruges | 0:11:37 | 0:11:40 | |

that set them apart from earlier manuscript illuminations. | 0:11:40 | 0:11:44 | |

They are truly exceptional, | 0:11:44 | 0:11:46 | |

and represent a real break from the Medieval past. | 0:11:46 | 0:11:49 | |

We are now firmly in the Renaissance. | 0:11:49 | 0:11:53 | |

'Even in the borders of these images, there's a new realism. | 0:11:56 | 0:12:01 | |

'A near-scientific observation of the natural world. | 0:12:01 | 0:12:04 | |

'These are achievements more usually associated with figures | 0:12:07 | 0:12:10 | |

'such as Van Eyck, who also worked in Bruges in the 15th century. | 0:12:10 | 0:12:15 | |

'At that time, | 0:12:15 | 0:12:17 | |

'skilled illuminators were seen as the equals of talented oil painters. | 0:12:17 | 0:12:21 | |

'The two worlds influenced each other, and some artists | 0:12:21 | 0:12:25 | |

'worked in both forms. | 0:12:25 | 0:12:26 | |

'But posterity has favoured the work which went on public display.' | 0:12:26 | 0:12:31 | |

There are some masterpieces of the Northern Renaissance | 0:12:32 | 0:12:35 | |

that remain largely unknown to this day, | 0:12:35 | 0:12:38 | |

because they don't hang on the walls of museums. | 0:12:38 | 0:12:41 | |

They're contained within the covers of manuscripts, | 0:12:41 | 0:12:44 | |

and locked within libraries. | 0:12:44 | 0:12:46 | |

'Yet it's in books of the time that some of the innovations | 0:12:47 | 0:12:51 | |

'of the artistic Renaissance first appear.' | 0:12:51 | 0:12:54 | |

We see an entirely new art genre here in Bruges. | 0:12:54 | 0:12:58 | |

The landscape painting. | 0:12:58 | 0:12:59 | |

Instead of filling illuminations with figures and narratives, | 0:12:59 | 0:13:03 | |

we now get landscape for landscape's sake. | 0:13:03 | 0:13:06 | |

'This is one of the very first European paintings | 0:13:08 | 0:13:12 | |

'to take the countryside as its chief subject. | 0:13:12 | 0:13:15 | |

'The way it captures the qualities of the natural world | 0:13:15 | 0:13:18 | |

'anticipates great names such as Constable. | 0:13:18 | 0:13:21 | |

'Yet it was painted not on canvas or wood, | 0:13:21 | 0:13:24 | |

'but on the pages of a Bruges manuscript | 0:13:24 | 0:13:26 | |

'called Treasure D'Histoire. | 0:13:26 | 0:13:28 | |

'Given their increasingly secular subjects, | 0:13:29 | 0:13:33 | |

'it's apt that Bruges manuscripts were produced | 0:13:33 | 0:13:36 | |

'not in monastic scriptoria, but in commercial workshops. | 0:13:36 | 0:13:40 | |

'Both the quality of the craftsmanship | 0:13:40 | 0:13:42 | |

'and the cutting edge style made Flemish workmanship fit for a king. | 0:13:42 | 0:13:47 | |

'But there was a further reason why Edward was familiar | 0:13:51 | 0:13:55 | |

'with the art of Bruges. | 0:13:55 | 0:13:56 | |

'When exiled from England by Henry VI, | 0:13:56 | 0:13:59 | |

'he had lived here in this mansion, | 0:13:59 | 0:14:01 | |

'which belonged to a noble friend.' | 0:14:01 | 0:14:04 | |

I can imagine Edward IV would have been impressed when he stayed here. | 0:14:04 | 0:14:09 | |

Bruges was a very wealthy city at this point, | 0:14:09 | 0:14:12 | |

stuffed full of craftspeople and artisans, | 0:14:12 | 0:14:15 | |

producing the very finest clothing, jewellery and of course manuscripts. | 0:14:15 | 0:14:20 | |

'The court Edward created on his return to England | 0:14:22 | 0:14:25 | |

'was a deliberate attempt to compete with the magnificence he'd witnessed | 0:14:25 | 0:14:30 | |

'in the Duchy of Burgundy. | 0:14:30 | 0:14:32 | |

'He succeeded not only in rebuilding the image of the English monarchy, | 0:14:33 | 0:14:37 | |

'but also restoring its strength. | 0:14:37 | 0:14:40 | |

'His reign was a long and peaceful one. | 0:14:40 | 0:14:43 | |

'Just how well Edward had managed to hold England together | 0:14:43 | 0:14:46 | |

'became obvious when he died in 1483. | 0:14:46 | 0:14:50 | |

'The Wars of the Roses erupted once more. | 0:14:54 | 0:14:57 | |

'They were only settled for good when the usurping Richard III | 0:14:59 | 0:15:04 | |

'was defeated in the Battle of Bosworth Field by the founder | 0:15:04 | 0:15:08 | |

'of one of the greatest royal dynasties, Henry Tudor. | 0:15:08 | 0:15:11 | |

'It was said he plucked Richard's discarded crown | 0:15:13 | 0:15:16 | |

'from a hawthorne bush, and his heraldry often incorporated this, | 0:15:16 | 0:15:21 | |

'along with the red dragon, which was on his standard at Bosworth, | 0:15:21 | 0:15:25 | |

'and the white greyhound | 0:15:25 | 0:15:27 | |

'of his Lancastrian ancestors. | 0:15:27 | 0:15:29 | |

'Though Henry and his descendants changed English history, | 0:15:29 | 0:15:33 | |

'at the start of his reign, | 0:15:33 | 0:15:35 | |

'it wasn't certain he could survive in the job. | 0:15:35 | 0:15:38 | |

'His claim to the throne was weak, depending on a female line | 0:15:38 | 0:15:41 | |

'and an illegitimate ancestor. | 0:15:41 | 0:15:44 | |

'So the image he sought to portray was different from the glamour | 0:15:44 | 0:15:48 | |

'favoured by Edward IV. | 0:15:48 | 0:15:50 | |

'And the mission for manuscripts in Henry's reign is to prove | 0:15:50 | 0:15:53 | |

'both his right to rule and his nobility.' | 0:15:53 | 0:15:57 | |

In order to bolster his claim to the throne, | 0:15:59 | 0:16:02 | |

Henry VII selects a very specific set of symbols | 0:16:02 | 0:16:05 | |

that will add legitimacy and mystique to the Tudor dynasty. | 0:16:05 | 0:16:09 | |

We find them throughout manuscripts associated with him, | 0:16:09 | 0:16:12 | |

and this one is full of them. | 0:16:12 | 0:16:14 | |

'The red dragon makes another appearance. | 0:16:16 | 0:16:19 | |

'It was the symbol of the last king of the ancient Britons, | 0:16:19 | 0:16:22 | |

'Cadwaladr, from whom Henry claimed descent. | 0:16:22 | 0:16:24 | |

'And later in the book, the dragon's entwined | 0:16:26 | 0:16:30 | |

'with another recurring symbol, the hawthorn bush with the crown. | 0:16:30 | 0:16:33 | |

'Other imagery reminds readers that Henry had united | 0:16:35 | 0:16:39 | |

'the warring houses of Lancaster and York.' | 0:16:39 | 0:16:42 | |

Here in the borders, | 0:16:42 | 0:16:44 | |

we can see that the War of the Roses has reached its symbolic conclusion. | 0:16:44 | 0:16:48 | |

Red and white roses intertwine to symbolise | 0:16:48 | 0:16:51 | |

the marriage between Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. | 0:16:51 | 0:16:55 | |

'On the same page, we have an image of the Tudor court. | 0:16:57 | 0:17:00 | |

'The King inspects this very book. | 0:17:00 | 0:17:03 | |

'What the figures of state have gathered to see is something | 0:17:03 | 0:17:06 | |

'very different to the history texts Edward IV would have shown them. | 0:17:06 | 0:17:11 | |

'At the front are pages of dense data. | 0:17:12 | 0:17:15 | |

'These are calculations of planetary movements | 0:17:15 | 0:17:18 | |

'by an Oxford academic, John Killingworth.' | 0:17:18 | 0:17:21 | |

What's interesting about this manuscript is that | 0:17:23 | 0:17:27 | |

these pages of mathematical information have been given | 0:17:27 | 0:17:30 | |

the royal treatment with the inclusion of these gold columns. | 0:17:30 | 0:17:33 | |

At Henry's court, science and scholarship more generally, | 0:17:33 | 0:17:37 | |

were held in the highest esteem, and Henry wanted to be their patron. | 0:17:37 | 0:17:42 | |

'Sponsoring learning was one way Henry could prove his worth, | 0:17:42 | 0:17:47 | |

'and compensate for the lowly status of some of his ancestors. | 0:17:47 | 0:17:53 | |

'These days, however, | 0:17:53 | 0:17:54 | |

'the manuscript wouldn't be classified as scientific. | 0:17:54 | 0:17:58 | |

'In modern terms, its subject is not astronomy, but astrology. | 0:18:01 | 0:18:05 | |

'Though at the time, the distinction between the two was less clear. | 0:18:07 | 0:18:11 | |

'Constellations have been plotted | 0:18:11 | 0:18:13 | |

'to divine what's written in the stars for the reader.' | 0:18:13 | 0:18:16 | |

'Later in the book, there's even a collection of ancient prophecies | 0:18:16 | 0:18:21 | |

'about the future of the English monarchy. | 0:18:21 | 0:18:23 | |

'Some attributed to Merlin! | 0:18:23 | 0:18:25 | |

'You can understand why the king this was all created for | 0:18:25 | 0:18:29 | |

'might have been anxious about his future.' | 0:18:29 | 0:18:32 | |

Henry was all too aware that his hold on the throne was vulnerable. | 0:18:33 | 0:18:37 | |

By the time this manuscript was made, | 0:18:37 | 0:18:40 | |

he'd already put down a rebellion. | 0:18:40 | 0:18:42 | |

So I can imagine a collection of texts that prophesises | 0:18:42 | 0:18:46 | |

the success of his family and the length of his reign | 0:18:46 | 0:18:49 | |

must have been quite appealing. And actually quite reassuring. | 0:18:49 | 0:18:54 | |

'But it's still a little strange to find science and magic | 0:18:57 | 0:19:01 | |

'jumbled up together in the library of a Christian king. | 0:19:01 | 0:19:05 | |

'To try to understand these apparent contradictions, | 0:19:08 | 0:19:11 | |

'I've come to Merton College in Oxford. | 0:19:11 | 0:19:14 | |

'This was where the mathematician | 0:19:18 | 0:19:20 | |

'who wrote some of the manuscript was a tutor. | 0:19:20 | 0:19:23 | |

'And the warden here at the time was one of Henry's closest courtiers, | 0:19:23 | 0:19:27 | |

'a bishop called Richard Fitzjames. | 0:19:27 | 0:19:30 | |

'He commissioned some sculpture which resembles | 0:19:30 | 0:19:34 | |

'the manuscript in both style and subject.' | 0:19:34 | 0:19:38 | |

We're looking at astrological symbols, | 0:19:41 | 0:19:44 | |

and they're all here. The spring ones starting with Aries, | 0:19:44 | 0:19:47 | |

the summer ones starting with Cancer, | 0:19:47 | 0:19:52 | |

then the autumn ones starting with Libra, the scales over there, | 0:19:52 | 0:19:56 | |

and then we've got the winter ones ending with Pisces. | 0:19:56 | 0:20:00 | |

Right next to the Royal Arms of Henry VII. | 0:20:00 | 0:20:04 | |

Yes, cos that's what's right here in the centre, isn't it? | 0:20:04 | 0:20:07 | |

-It's dominating the whole composition. -Absolutely. | 0:20:07 | 0:20:11 | |

And I think you'd have to say that Henry VII is ruling the cosmos. | 0:20:11 | 0:20:14 | |

It's as powerful a statement as that. | 0:20:14 | 0:20:17 | |

And they've been put here by a bishop. You see, that surprises me. | 0:20:20 | 0:20:23 | |

It might seem a bit strange to us today to imagine that a bishop | 0:20:23 | 0:20:27 | |

would be interested in this, but you mustn't think about it like that. | 0:20:27 | 0:20:31 | |

Remember, it's 1497, it's the height of the Northern Renaissance, | 0:20:31 | 0:20:36 | |

and astrology isn't a kind of thing for people in Sunday magazines. | 0:20:36 | 0:20:40 | |

We're here in Merton College, | 0:20:40 | 0:20:42 | |

so some of the most famous astrologers were trained here, | 0:20:42 | 0:20:45 | |

like John Ashenden, who was thought to have predicted the Plague. | 0:20:45 | 0:20:48 | |

So, astrology was part of the science of the day. | 0:20:48 | 0:20:52 | |

'During Henry's reign, | 0:20:58 | 0:21:01 | |

'this beautiful oak-panelled roof was built for Merton's library. | 0:21:01 | 0:21:06 | |

'Once again, there's Henry VII's coat of arms | 0:21:06 | 0:21:09 | |

'alongside other Tudor insignia. | 0:21:09 | 0:21:11 | |

'And in 1502, exactly when the ceiling was constructed, | 0:21:14 | 0:21:19 | |

'another astrological manuscript was presented to Henry VII.' | 0:21:19 | 0:21:24 | |

OK, so, what have we got here, then? | 0:21:28 | 0:21:30 | |

Well, now it's time to introduce you to William Parron. | 0:21:30 | 0:21:34 | |

Now, William Parron is an Italian astrologer, | 0:21:34 | 0:21:38 | |

and he is the first court astrologer that any English king takes on. | 0:21:38 | 0:21:42 | |

What he's done here is cast a chart for Prince Henry of York, | 0:21:42 | 0:21:47 | |

who's the future King Henry VIII. | 0:21:47 | 0:21:48 | |

-It's a personal horoscope. -Absolutely. This is special. | 0:21:48 | 0:21:52 | |

Astrology in this period is a royal art, | 0:21:52 | 0:21:54 | |

something you pay a specialist to do for you. | 0:21:54 | 0:21:57 | |

You can't just pick up a newspaper and have a reading done. | 0:21:57 | 0:22:01 | |

It has to be done for you by someone who's got | 0:22:01 | 0:22:03 | |

the nous and the professionalism to do it. | 0:22:03 | 0:22:05 | |

-Overall, what have we got? -We've got the classic horoscope diagram, | 0:22:05 | 0:22:10 | |

which is a square within a square. | 0:22:10 | 0:22:13 | |

You'd get your astronomical data, OK, here's the planets and so on, | 0:22:13 | 0:22:17 | |

that's the data there. And then you would discuss it theme by theme. | 0:22:17 | 0:22:22 | |

So, life, wealth, death, and in the centre, | 0:22:22 | 0:22:29 | |

what is in the centre? Of course, the Earth! | 0:22:29 | 0:22:31 | |

We've in fact got what was called a "mappa mundi," a map of the world. | 0:22:31 | 0:22:37 | |

It makes more sense round that way. | 0:22:37 | 0:22:39 | |

It sure does. Clearly, this is the north, cos there's Greenland. | 0:22:39 | 0:22:43 | |

And fascinatingly, this strange sort of nodule here says "Angland". | 0:22:43 | 0:22:48 | |

-Angland, yeah. -We can see Europa. | 0:22:48 | 0:22:51 | |

There seems to be a lot of detail here, | 0:22:51 | 0:22:54 | |

layer upon layer of meaning. What does this tell us, | 0:22:54 | 0:22:57 | |

do you think, about the mindset of Henry at this stage? | 0:22:57 | 0:23:01 | |

Well, I think Henry was impressed by the magnificence | 0:23:01 | 0:23:04 | |

and glamour of astrology. | 0:23:04 | 0:23:06 | |

It was the most sophisticated stuff. | 0:23:06 | 0:23:09 | |

Other princes might have been able to send explorers around Africa. | 0:23:09 | 0:23:14 | |

Henry was interested in bringing to his court Italian humanists. | 0:23:14 | 0:23:19 | |

He was interested in educating his children, giving them | 0:23:19 | 0:23:22 | |

a very sophisticated grasp of languages. | 0:23:22 | 0:23:26 | |

And I think that's what we see here, | 0:23:26 | 0:23:28 | |

that astrology was a window into a way of looking at the world. | 0:23:28 | 0:23:32 | |

It was a scientific and modern way of looking at the world too. | 0:23:32 | 0:23:35 | |

'There is, however, an obvious problem when astrology is | 0:23:38 | 0:23:42 | |

'treated as a science, which this manuscript demonstrates.' | 0:23:42 | 0:23:46 | |

In the text following the birth chart, | 0:23:46 | 0:23:49 | |

Parron makes a number of predictions. | 0:23:49 | 0:23:51 | |

One is that the future Henry VIII will be a loyal Catholic | 0:23:51 | 0:23:55 | |

and happily married father to many sons. | 0:23:55 | 0:23:58 | |

'And for Henry VII, | 0:23:59 | 0:24:01 | |

'what must have raised doubts is a prediction that his queen, | 0:24:01 | 0:24:04 | |

'Elizabeth of York, would live to at least to the age of 80.' | 0:24:04 | 0:24:08 | |

Elizabeth died within a year of this book being written, aged just 37. | 0:24:08 | 0:24:15 | |

William Parron disappeared soon after from the English court, | 0:24:15 | 0:24:19 | |

and from historical records. | 0:24:19 | 0:24:21 | |

'Fortunately, the scholarship that Henry VII sponsored | 0:24:24 | 0:24:27 | |

'wasn't confined to stargazing. | 0:24:27 | 0:24:29 | |

'Here, he's being presented with a work of Greek history, | 0:24:31 | 0:24:34 | |

'Xenophon's Anabasis. | 0:24:34 | 0:24:36 | |

'The Frenchman who translated it, Claude de Seyssel, visited England | 0:24:37 | 0:24:41 | |

'in 1506, and noted an intriguing detail about the English King.' | 0:24:41 | 0:24:47 | |

De Seyssel has been shown Henry's newly constructed library. | 0:24:49 | 0:24:54 | |

He writes that it is "tres belle et tres bien acoustree." | 0:24:54 | 0:24:58 | |

Very beautiful and very well appointed. | 0:24:58 | 0:25:01 | |

'That room was probably at Henry's palace in Richmond, | 0:25:03 | 0:25:06 | |

'long since demolished. | 0:25:06 | 0:25:07 | |

'But there are other accounts of it. | 0:25:09 | 0:25:12 | |

'One involves Catherine of Aragon, who'd come to England in 1502.' | 0:25:12 | 0:25:17 | |

When Catherine's entourage returned to Spain, she needed cheering up, | 0:25:18 | 0:25:22 | |

so Henry took her and her ladies-in-waiting to his library. | 0:25:22 | 0:25:26 | |

We've got an account of this visit. | 0:25:26 | 0:25:28 | |

Apparently, he "showed unto her many goodly pleasant books, | 0:25:28 | 0:25:32 | |

"of works full delightful. | 0:25:32 | 0:25:34 | |

"Sage, merry and also reet cunning." | 0:25:34 | 0:25:37 | |

He clearly knew how to show a girl a good time. | 0:25:37 | 0:25:39 | |

'A library at this time appears to have been | 0:25:42 | 0:25:45 | |

'something rare and exciting.' | 0:25:45 | 0:25:47 | |

It's hard to imagine the novelty, in the 16th century, | 0:25:49 | 0:25:52 | |

of seeing a whole room exclusively dedicated to the display of books. | 0:25:52 | 0:25:58 | |

In fact, we simply don't know | 0:25:58 | 0:25:59 | |

what this royal library looked like at all. | 0:25:59 | 0:26:02 | |

'Previously, only religious and academic institutions | 0:26:05 | 0:26:08 | |

'kept large collections of books. Merton College was one of them. | 0:26:08 | 0:26:13 | |

'But back in 1502, the books in this library | 0:26:13 | 0:26:16 | |

'wouldn't have been on shelves. | 0:26:16 | 0:26:19 | |

'They were kept in chests. | 0:26:20 | 0:26:23 | |

'This one was used by the university at that time. | 0:26:23 | 0:26:26 | |

'Records suggest Edward IV stored his books in something similar. | 0:26:26 | 0:26:30 | |

'Although no Tudor palace libraries survive, | 0:26:33 | 0:26:37 | |

'something still remains which helps us imagine their splendour.' | 0:26:37 | 0:26:42 | |

This is an incredibly rare survival. This is an original Tudor binding. | 0:26:48 | 0:26:54 | |

'This book, a guide to the Holy Land, | 0:26:55 | 0:26:58 | |

'was noted in an inventory of 1547 as being covered | 0:26:58 | 0:27:01 | |

'with the same embroidered velvet we can still see today. | 0:27:01 | 0:27:04 | |

'Once, hundreds of books in the royal library | 0:27:08 | 0:27:11 | |

'were bound as magnificently as this. | 0:27:11 | 0:27:14 | |

'But the covers have fared far worse than the contents. | 0:27:14 | 0:27:18 | |

'Now, just a handful of them remain.' | 0:27:18 | 0:27:21 | |

It's only when you see this binding that you can fully appreciate | 0:27:22 | 0:27:26 | |

the impact that a royal manuscript once had. | 0:27:26 | 0:27:29 | |

Even before you glimpse the wonderful artwork within, | 0:27:29 | 0:27:32 | |

this impresses and dazzles. | 0:27:32 | 0:27:36 | |

They say you can't judge a book by its cover, | 0:27:36 | 0:27:38 | |

but it's clear that many people did. | 0:27:38 | 0:27:40 | |

'That means we're in danger of misunderstanding these objects, | 0:27:40 | 0:27:45 | |

'because so few of them retain their intended appearance. | 0:27:45 | 0:27:49 | |

'Which is why I've come to a place where the traditions | 0:27:52 | 0:27:55 | |

'so valued by Medieval kings are still being followed.' | 0:27:55 | 0:28:00 | |

'James Brockman has been re-binding historic books for 45 years, | 0:28:01 | 0:28:07 | |

'and now his son Stuart has joined him in the family business. | 0:28:07 | 0:28:11 | |

'To repair and preserve ancient books, James and Stuart | 0:28:11 | 0:28:15 | |

'have learned the same processes used by their original creators.' | 0:28:15 | 0:28:19 | |

We'd like to think that if a binder from 800 years ago came here, | 0:28:19 | 0:28:24 | |

he would recognise what we're doing, | 0:28:24 | 0:28:27 | |

because we're using all the original techniques. | 0:28:27 | 0:28:30 | |

'Just as they were in royal manuscripts, | 0:28:30 | 0:28:33 | |

'the pages of these books are sewn together by hand.' | 0:28:33 | 0:28:37 | |

Effectively, you're stitching the pages above to the ones below. | 0:28:37 | 0:28:41 | |

That's right. We're locking one section to the previous one. | 0:28:41 | 0:28:44 | |

'The quires, three or four pages folded inside each other, | 0:28:45 | 0:28:49 | |

'are bound together by tying the thread round tougher cords, | 0:28:49 | 0:28:54 | |

'then passing it through the pages.' | 0:28:54 | 0:28:56 | |

-Is that right? -That's it, yeah. | 0:28:56 | 0:28:58 | |

I've seen pictures of this. | 0:28:58 | 0:29:00 | |

I never thought I'd actually have a chance to do it myself. | 0:29:00 | 0:29:04 | |

-How old is this book again? -Er, it's a printed book from about 1480. | 0:29:04 | 0:29:08 | |

-No pressure, then? -No pressure at all, none at all. | 0:29:08 | 0:29:11 | |

And how long does it take? | 0:29:11 | 0:29:12 | |

A book of this size probably takes around a day's work. | 0:29:12 | 0:29:15 | |

-A whole day. -But it's worth it. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:17 | |

The strength of the structure will last 300 years. | 0:29:17 | 0:29:20 | |

'When all the pages are stitched together, | 0:29:22 | 0:29:25 | |

'a manuscript is knocked into shape, | 0:29:25 | 0:29:27 | |

'before being clamped into a laying press to treat the edges.' | 0:29:27 | 0:29:31 | |

And this is actual gold? | 0:29:32 | 0:29:34 | |

Yes, it's almost pure. | 0:29:34 | 0:29:36 | |

Pure gold. | 0:29:36 | 0:29:38 | |

Gosh, it's so light, it's just floating as you move it. | 0:29:38 | 0:29:42 | |

And then you cut the gold... | 0:29:42 | 0:29:44 | |

into strips. | 0:29:44 | 0:29:47 | |

And then these are gilders tips. | 0:29:47 | 0:29:49 | |

Right. Oh, wow, yes, almost like cat hair or something. | 0:29:49 | 0:29:52 | |

-Yes. I'm not sure what it is. -Really, really soft. -Very fine. | 0:29:52 | 0:29:56 | |

Then you need a bit of grease from your hair, like this. | 0:29:56 | 0:29:58 | |

-And then you can pick the gold up on the gilders tip. -Wow. | 0:30:00 | 0:30:06 | |

I love the idea that this was being done 300 years ago. | 0:30:06 | 0:30:09 | |

People wiping their hair! | 0:30:09 | 0:30:12 | |

'The Royal Accounts of 1480 record the King's books being gilded | 0:30:12 | 0:30:17 | |

'in just this way, and covered and garnished, | 0:30:17 | 0:30:20 | |

'at a cost of thousands of pounds each in today's money.' | 0:30:20 | 0:30:25 | |

I like that, it's like the illumination inside's | 0:30:25 | 0:30:28 | |

-being brought out. -Yes, exactly. | 0:30:28 | 0:30:30 | |

This burnishing gives us the brilliant gold gilt edges | 0:30:30 | 0:30:33 | |

that we get on early manuscripts, and here's an example. | 0:30:33 | 0:30:36 | |

See, this really excites me. | 0:30:36 | 0:30:38 | |

As a kid, I used to love the gold edges on things like diaries | 0:30:38 | 0:30:42 | |

and books, but it is an insight for me into the mind | 0:30:42 | 0:30:46 | |

of the kings that commissioned these manuscripts. | 0:30:46 | 0:30:49 | |

They clearly want these things to look good from the outside. | 0:30:49 | 0:30:52 | |

-It's not just what's inside. -No. The gold really dresses the edges. | 0:30:52 | 0:30:56 | |

-It turns the book into a treasure, doesn't it? -It does. | 0:30:56 | 0:30:59 | |

'The next stage is to give the book its hard covers. | 0:31:01 | 0:31:05 | |

'Stuart and James plane these solid wooden boards from oak. | 0:31:05 | 0:31:10 | |

'Then comes the gift wrapping.' | 0:31:10 | 0:31:12 | |

We're thinking of maybe using this wonderful purple here | 0:31:14 | 0:31:17 | |

for covering this little manuscript. | 0:31:17 | 0:31:19 | |

'Many ancient books were rebound in leather during the 19th century. | 0:31:19 | 0:31:24 | |

'But the Brockmans use the fabrics favoured by Medieval monarchs. | 0:31:24 | 0:31:30 | |

'Crimson velvet was the most luxurious. | 0:31:30 | 0:31:33 | |

'One yard cost as much as 60 days of a mason's labour.' | 0:31:33 | 0:31:37 | |

And I cut it plenty generous, so there's plenty of turning, | 0:31:39 | 0:31:42 | |

top and bottom. | 0:31:42 | 0:31:43 | |

Every aspect of the process you've shown me seems so time consuming. | 0:31:43 | 0:31:48 | |

How long would it take to complete a binding? | 0:31:48 | 0:31:51 | |

I suppose a manuscript like this would probably take around 100 hours. | 0:31:51 | 0:31:55 | |

-100 hours of actual labour, working? -Yes, yes. | 0:31:55 | 0:31:57 | |

'When you add on the months of skilled craft put in by the scribes | 0:32:00 | 0:32:04 | |

'and illuminators, and the months required to make fine vellum, | 0:32:04 | 0:32:08 | |

'you realise how labour intensive the production of manuscripts was. | 0:32:08 | 0:32:13 | |

'And why kings were among the few people who could ever afford them. | 0:32:13 | 0:32:18 | |

'And here's one the Tudors made earlier.' | 0:32:23 | 0:32:26 | |

This is a manuscript that makes me go weak at the knees. | 0:32:27 | 0:32:30 | |

Probably the most magnificent binding to survive from Tudor times. | 0:32:30 | 0:32:35 | |

And it's clear it's from | 0:32:35 | 0:32:37 | |

the court of Henry VII | 0:32:37 | 0:32:39 | |

because it's got his coat of arms here in the middle, | 0:32:39 | 0:32:42 | |

and his livery, the portcullis with the green and white background. | 0:32:42 | 0:32:47 | |

We haven't entered the manuscript yet and it screams magnificence. | 0:32:47 | 0:32:51 | |

You can see the velvet, burgundy velvet. | 0:32:51 | 0:32:54 | |

And over here, you can see how the binding was originally stitched. | 0:32:54 | 0:32:59 | |

These are the ropes, just showing through on the velvet. | 0:32:59 | 0:33:02 | |

And the clasps are breathtaking in their detail. | 0:33:03 | 0:33:08 | |

They're silver, they look like they've been gilded, | 0:33:08 | 0:33:11 | |

with a rose in the middle and these amazing angels | 0:33:11 | 0:33:15 | |

that attach to these threads, with the gold woven all the way through. | 0:33:15 | 0:33:20 | |

There's even the original tassel here. | 0:33:20 | 0:33:24 | |

It's just amazing that this has survived | 0:33:24 | 0:33:26 | |

in such remarkable condition. | 0:33:26 | 0:33:28 | |

'The antique velvet is now so delicate, | 0:33:30 | 0:33:33 | |

'the edges can no longer be safely tucked in, | 0:33:33 | 0:33:35 | |

'and the book requires assistance to open. | 0:33:35 | 0:33:38 | |

'I'm wearing gloves for once, | 0:33:38 | 0:33:40 | |

'because contact with the metal clasps could corrode them. | 0:33:40 | 0:33:44 | |

'And what's inside the covers is no less impressive.' | 0:33:44 | 0:33:48 | |

There's this beautiful pink damask on the inside, | 0:33:48 | 0:33:51 | |

and down here, these silver tins | 0:33:51 | 0:33:53 | |

attached to the manuscript. | 0:33:53 | 0:33:56 | |

They've got the King's rose and crown on them. | 0:33:56 | 0:34:00 | |

And if I open one up... | 0:34:00 | 0:34:02 | |

..like this...inside, there's another image. | 0:34:04 | 0:34:09 | |

Here we have the King enthroned in this architectural setting, | 0:34:09 | 0:34:15 | |

wielding the regalia, the orb and sceptre. | 0:34:15 | 0:34:19 | |

These are wax seals. | 0:34:20 | 0:34:23 | |

'They're required because this manuscript is actually | 0:34:25 | 0:34:28 | |

'a legal contract. | 0:34:28 | 0:34:29 | |

'It's an agreement between Henry and Westminster Abbey. | 0:34:29 | 0:34:34 | |

'The King is depicted giving the monks this very manuscript.' | 0:34:34 | 0:34:39 | |

More usually, legal documents, even royal ones, would take the form | 0:34:39 | 0:34:44 | |

of a single piece of parchment, so the fact that this is in book form, | 0:34:44 | 0:34:48 | |

and it's so lavishly coloured, means it must be something pretty special. | 0:34:48 | 0:34:53 | |

'This is Henry VII making plans for his afterlife. | 0:34:56 | 0:35:00 | |

'He's specifying the exact rituals he expects to be performed for him.' | 0:35:01 | 0:35:06 | |

So here, he's put in arrangements for the souls of him and his family | 0:35:10 | 0:35:15 | |

to be prayed for in perpetuity. | 0:35:15 | 0:35:17 | |

It says here, "Shall endure daily mass | 0:35:17 | 0:35:21 | |

"and divine service for the good and prosperous estate | 0:35:21 | 0:35:24 | |

"of our said sovereign Lord, the King, and the souls of his family." | 0:35:24 | 0:35:29 | |

'This isn't just a wish list, it's a binding contract, | 0:35:30 | 0:35:34 | |

'which was hand-made in duplicate. | 0:35:34 | 0:35:37 | |

'One copy was with the King, and the other with the Abbey.' | 0:35:37 | 0:35:41 | |

You can see here, there's a wavy line that's been cut into | 0:35:41 | 0:35:45 | |

the top of the book. | 0:35:45 | 0:35:46 | |

If we had the other copy, the two would fit together | 0:35:46 | 0:35:50 | |

and the wavy lines would interlock. | 0:35:50 | 0:35:52 | |

That's why this kind of legal document is called an indenture. | 0:35:52 | 0:35:55 | |

That's the French for "toothed". | 0:35:55 | 0:35:58 | |

This document doesn't just detail the prayers that are to be said | 0:35:59 | 0:36:03 | |

for the souls of the King and his family after death. | 0:36:03 | 0:36:06 | |

It also gives detailed information about his tomb. | 0:36:06 | 0:36:09 | |

It says here, | 0:36:09 | 0:36:10 | |

"A tomb there shall be made for the interment of the body | 0:36:10 | 0:36:13 | |

"of our said sovereign Lord, the King, | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

"and a chapel of metal made thereabouts." | 0:36:16 | 0:36:20 | |

'When Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church, | 0:36:25 | 0:36:28 | |

'Westminster lost the monks his father imagined | 0:36:28 | 0:36:31 | |

'would still be praying for him today. | 0:36:31 | 0:36:33 | |

'But Henry VII's chapel | 0:36:35 | 0:36:37 | |

'is preserved just as the manuscript specified. | 0:36:37 | 0:36:41 | |

'It's one of the finest late-Gothic buildings in Europe. | 0:36:44 | 0:36:49 | |

'Around the walls are 95 original statues of saints. | 0:36:54 | 0:36:58 | |

'It's one of the most visibly Catholic spaces | 0:36:58 | 0:37:01 | |

'still remaining from this period of English history. | 0:37:01 | 0:37:05 | |

'It was intended not just as a royal resting place, | 0:37:05 | 0:37:09 | |

'but also a shrine to the Virgin Mary. | 0:37:09 | 0:37:12 | |

'Henry was a supporter of the cult of the Immaculate Conception.' | 0:37:12 | 0:37:17 | |

It's hard to believe that imagery like this, a generation later, | 0:37:17 | 0:37:22 | |

was being destroyed at the behest of Henry's own son. | 0:37:22 | 0:37:26 | |

'Only a few decades before the break with Rome, it's clear that England | 0:37:36 | 0:37:41 | |

'was a deeply Catholic nation, and its King shared that faith. | 0:37:41 | 0:37:45 | |

'Henry's tomb remains the centrepiece of the chapel. | 0:37:48 | 0:37:52 | |

'As one contemporary wrote, | 0:37:59 | 0:38:01 | |

'"He dwelleth more richly dead than he did at any of his palaces."' | 0:38:01 | 0:38:07 | |

As a statement of the permanence of your family's position, | 0:38:07 | 0:38:11 | |

this mausoleum's hard to argue with. | 0:38:11 | 0:38:14 | |

'By the time he'd died, on the 21st of April 1509, | 0:38:16 | 0:38:21 | |

'Henry had successfully transformed the shaky Tudor claim to the throne | 0:38:21 | 0:38:25 | |

'into what looked like a permanent hold on kingship. | 0:38:25 | 0:38:29 | |

'His son and heir was determined to build on that inheritance. | 0:38:35 | 0:38:40 | |

'Henry VIII marks the culmination | 0:38:41 | 0:38:43 | |

'of the English royal manuscript tradition. | 0:38:43 | 0:38:46 | |

'The imagery of monarchy is never more complex, | 0:38:46 | 0:38:50 | |

'revealing or magnificent than in his reign.' | 0:38:50 | 0:38:53 | |

'This manuscript dates from when Henry was just 25 years old, | 0:38:55 | 0:39:00 | |

'but already in the seventh year of his rule. | 0:39:00 | 0:39:03 | |

'It was a gift from an Antwerp merchant, | 0:39:03 | 0:39:06 | |

'and begins with a long poem praising the King.' | 0:39:06 | 0:39:09 | |

And here is Henry's name, | 0:39:09 | 0:39:13 | |

highlighted in gold. | 0:39:13 | 0:39:14 | |

'The artwork is stuffed with symbols of England and the Tudors. | 0:39:17 | 0:39:21 | |

'Everything in this image has a meaning.' | 0:39:21 | 0:39:23 | |

Henry was a famously accomplished individual. | 0:39:26 | 0:39:29 | |

He was very well educated, he spoke several languages. | 0:39:29 | 0:39:32 | |

He wrote books and he was also an excellent sportsman. | 0:39:32 | 0:39:37 | |

And this is clearly a gift | 0:39:37 | 0:39:39 | |

intended for a Renaissance prince. | 0:39:39 | 0:39:41 | |

In many ways, this frontispiece | 0:39:41 | 0:39:44 | |

is an intellectual game | 0:39:44 | 0:39:45 | |

or challenge, where these complex | 0:39:45 | 0:39:48 | |

visual symbols wrap around | 0:39:48 | 0:39:50 | |

and intertwine with | 0:39:50 | 0:39:52 | |

the allegorical poem within. | 0:39:52 | 0:39:55 | |

'The verse describes how a single root | 0:39:56 | 0:39:59 | |

'here produces different flowers. | 0:39:59 | 0:40:01 | |

'Since the blooms are clearly Tudor roses, | 0:40:01 | 0:40:04 | |

'they can be identified as Henry and his sisters, Margaret and Mary. | 0:40:04 | 0:40:10 | |

'The King, of course, is the tallest. | 0:40:10 | 0:40:14 | |

'Growing by the side of the English rosebush | 0:40:14 | 0:40:17 | |

'is an exotic pomegranate tree, symbol of Henry's Queen at the time, | 0:40:17 | 0:40:22 | |

'Catherine of Aragon.' | 0:40:22 | 0:40:24 | |

It's heavy with fruit that's literally bursting open, | 0:40:24 | 0:40:28 | |

and it reflects Henry's desire for a male heir. | 0:40:28 | 0:40:32 | |

'All of this grows, naturally enough, in a garden. | 0:40:34 | 0:40:37 | |

'And because it's the garden of England, it's on an island, | 0:40:37 | 0:40:41 | |

'and heavily defended.' | 0:40:41 | 0:40:43 | |

This is fortress England. | 0:40:43 | 0:40:46 | |

It's strong and secure under Henry, and even though it's a garden, | 0:40:46 | 0:40:50 | |

it's protected by warships. | 0:40:50 | 0:40:53 | |

'The shape of the rosebush is also significant. | 0:40:57 | 0:41:01 | |

'It's the outline of a musical instrument, a lyre.' | 0:41:01 | 0:41:05 | |

Alongside the specially produced | 0:41:07 | 0:41:10 | |

poetry and art, | 0:41:10 | 0:41:11 | |

this manuscript is full of music, | 0:41:11 | 0:41:14 | |

composed to delight the King. | 0:41:14 | 0:41:16 | |

'The first piece is written in this novel, circular form, | 0:41:18 | 0:41:21 | |

'and turns the previous pages' poetry into song.' | 0:41:21 | 0:41:26 | |

The way that the notation spirals around the rose inside | 0:41:26 | 0:41:31 | |

reinforces this idea of the fortress on the frontispiece. | 0:41:31 | 0:41:36 | |

Henry is probably the most musical monarch England's ever produced. | 0:41:36 | 0:41:40 | |

From the time of his coronation, he kept at least 25 musicians at court, | 0:41:40 | 0:41:44 | |

and he composed music himself. | 0:41:44 | 0:41:46 | |

So, of course, he'd be able to read this notation, | 0:41:46 | 0:41:49 | |

but he'd also be able to read the symbolism. | 0:41:49 | 0:41:53 | |

'Presumably, this piece was once performed in Henry's court, | 0:41:53 | 0:41:58 | |

'but because it wasn't published elsewhere, it never reached | 0:41:58 | 0:42:01 | |

'a wider audience.' | 0:42:01 | 0:42:02 | |

It's sad to think that so much creativity has been | 0:42:02 | 0:42:06 | |

poured into this gift for the King, | 0:42:06 | 0:42:08 | |

and yet it went unheard for centuries, locked away in a library. | 0:42:08 | 0:42:14 | |

CHOIR SINGS | 0:42:16 | 0:42:19 | |

'In recent years, however, the piece has been rediscovered | 0:42:33 | 0:42:37 | |

'by early music specialists, such as the Brabant Ensemble.' | 0:42:37 | 0:42:41 | |

This is such evocative music. | 0:42:55 | 0:42:58 | |

It's so strange to think that this was written | 0:42:58 | 0:43:01 | |

for the ears of the King 500 years ago. | 0:43:01 | 0:43:04 | |

It almost sounds odd or discordant in places, | 0:43:18 | 0:43:21 | |

and I think that's because I can hear the spiralling notes, | 0:43:21 | 0:43:26 | |

the voices overlapping with each other and the pitch changing, | 0:43:26 | 0:43:29 | |

just like we see it depicted in the manuscript. | 0:43:29 | 0:43:32 | |

Out of all the manuscripts I've encountered, | 0:43:45 | 0:43:47 | |

this is the most multi-dimensional. | 0:43:47 | 0:43:50 | |

I can read the words, I can see the notes | 0:43:50 | 0:43:53 | |

and the beautiful illuminations, and I can hear it. | 0:43:53 | 0:43:56 | |

'There are several other pieces of music written for the manuscript. | 0:44:12 | 0:44:16 | |

'And nearly all of them share a particular theme.' | 0:44:17 | 0:44:20 | |

They're singing praise for the Virgin Mary, | 0:44:26 | 0:44:29 | |

and this reminds me that, before his divorce, | 0:44:29 | 0:44:33 | |

of course, Henry was a famously devout Catholic. | 0:44:33 | 0:44:37 | |

But specifically, they're referring to her | 0:44:37 | 0:44:40 | |

as "magnificent channel, excellent vessel." | 0:44:40 | 0:44:43 | |

This is a song glorifying childbirth. | 0:44:43 | 0:44:48 | |

'It was a subject close to Henry's heart. | 0:44:53 | 0:44:55 | |

'Anyone hearing this in 1516 would have thought | 0:44:55 | 0:44:58 | |

'of Catherine of Aragon, and the expectation that | 0:44:58 | 0:45:02 | |

'she would soon produce a male heir to the Tudor line. | 0:45:02 | 0:45:06 | |

'Of course, the consequences when she failed to do so | 0:45:06 | 0:45:09 | |

'changed England's history.' | 0:45:09 | 0:45:11 | |

'In the British Library, there's evidence of the woman | 0:45:16 | 0:45:19 | |

'who replaced Catherine in Henry's affection, and inspired him | 0:45:19 | 0:45:23 | |

'to seek first divorce and then a break with the Roman church.' | 0:45:23 | 0:45:28 | |

This is a personal prayer book that was in use | 0:45:30 | 0:45:34 | |

within the royal household. | 0:45:34 | 0:45:36 | |

Inside it, we can find evidence | 0:45:36 | 0:45:38 | |

that the early readers' minds | 0:45:38 | 0:45:39 | |

weren't always on the sacred contents. | 0:45:39 | 0:45:43 | |

'Turning the pages, we find an image of the Man of Sorrows, | 0:45:45 | 0:45:48 | |

'from the Book of Isaiah. | 0:45:48 | 0:45:50 | |

'It's a sacred work of art, but King Henry had no qualms | 0:45:50 | 0:45:54 | |

'about making use of it as part of a love letter to Anne Boleyn.' | 0:45:54 | 0:45:58 | |

This is the handwriting of Henry VIII, | 0:45:59 | 0:46:02 | |

and he's written here in French, | 0:46:02 | 0:46:04 | |

"If you remember me in your prayers, | 0:46:04 | 0:46:07 | |

"as strongly as I adore you, | 0:46:07 | 0:46:09 | |

"I shall hardly be forgotten, for I am yours. Henry R." | 0:46:09 | 0:46:13 | |

It's such a personal note to find written in the King's own hand, | 0:46:14 | 0:46:19 | |

and it really gives this sense of | 0:46:19 | 0:46:22 | |

the lovesick individual. | 0:46:22 | 0:46:24 | |

'Like a schoolboy sending a note round the classroom, the King | 0:46:26 | 0:46:30 | |

'must have then passed on the manuscript to his beloved, | 0:46:30 | 0:46:33 | |

'because on another page, there's some different handwriting.' | 0:46:33 | 0:46:36 | |

Here is Anne Boleyn's response. | 0:46:37 | 0:46:41 | |

She's written, | 0:46:41 | 0:46:42 | |

"Be daily proof you shall me find, | 0:46:42 | 0:46:45 | |

"to be to you both loving and kind." | 0:46:45 | 0:46:48 | |

And it's interesting, the image she's chosen | 0:46:48 | 0:46:51 | |

to write this underneath, | 0:46:51 | 0:46:52 | |

it's the Annunciation. | 0:46:52 | 0:46:54 | |

The Angel Gabriel is telling Mary that she will conceive a son. | 0:46:54 | 0:46:59 | |

And given that a son is the thing Henry most wants in the world, | 0:46:59 | 0:47:03 | |

Anne is clearly saying what the King wants to hear. | 0:47:03 | 0:47:06 | |

'Henry's determination to wed Anne led, of course, | 0:47:14 | 0:47:17 | |

'to England's break with the Roman Catholic Church. | 0:47:17 | 0:47:21 | |

'The Reformation caused the destruction not just of monasteries | 0:47:21 | 0:47:25 | |

'across the country, but also many of their illuminated manuscripts.' | 0:47:25 | 0:47:30 | |

'The act that established the Book of Common Prayer specifically called | 0:47:32 | 0:47:36 | |

'for the abolishing and putting away of diverse books and images. | 0:47:36 | 0:47:42 | |

'Anything which seemed too redolent of the old religion.' | 0:47:42 | 0:47:46 | |

"All books used for the service of the Church, | 0:47:47 | 0:47:50 | |

"by the King's majesty, shall be clearly and utterly abolished, | 0:47:50 | 0:47:55 | |

"extinguished and forbidden forever to be used or kept in this realm." | 0:47:55 | 0:48:00 | |

I feel real sorrow at these words, when I think about the thousands | 0:48:00 | 0:48:04 | |

of beautiful manuscripts that must have been lost. | 0:48:04 | 0:48:08 | |

'Not even royal manuscripts escaped the destruction. | 0:48:13 | 0:48:17 | |

'This is the only page that survives from a choir book, | 0:48:19 | 0:48:22 | |

'commissioned in the 1470s by Margaret of York, | 0:48:22 | 0:48:26 | |

'the sister of Edward IV. | 0:48:26 | 0:48:27 | |

'The royal family sponsored the house of friars in Greenwich, | 0:48:27 | 0:48:32 | |

'who were thought to have used this in worship, | 0:48:32 | 0:48:34 | |

'until they were abolished by the Reformation.' | 0:48:34 | 0:48:37 | |

The quality of this single leaf is exquisite. | 0:48:39 | 0:48:42 | |

You can really tell it was a royal commission. | 0:48:42 | 0:48:45 | |

The details on the leaves, the flowers with shadows underneath, | 0:48:45 | 0:48:49 | |

and then this amazing miniature showing King David. | 0:48:49 | 0:48:52 | |

Really beautiful treatment of his hair and his face. | 0:48:52 | 0:48:56 | |

But even something as beautiful as this | 0:48:57 | 0:49:00 | |

wasn't exempt from the purges of the Reformation. | 0:49:00 | 0:49:04 | |

The rest of the book that this page was a part of has been destroyed. | 0:49:04 | 0:49:09 | |

This is the only page that remains. It's survived by accident, really. | 0:49:09 | 0:49:14 | |

It's been re-used as some sort of a wrapper. | 0:49:14 | 0:49:17 | |

It's been folded down the middle, | 0:49:17 | 0:49:19 | |

and people have even been practising their handwriting | 0:49:19 | 0:49:22 | |

in-between the notation. | 0:49:22 | 0:49:24 | |

To me, it's quite tragic that this is all that's left | 0:49:24 | 0:49:28 | |

of what was previously a magnificent Catholic manuscript. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:32 | |

'While the art of England's old religion was being destroyed, | 0:49:44 | 0:49:48 | |

'a very special prayer book had been made | 0:49:48 | 0:49:51 | |

'for the head of its new church.' | 0:49:51 | 0:49:54 | |

'This is a Psalter, an edition of the Book of Psalms. | 0:49:55 | 0:49:58 | |

'Many English monarchs before Henry had owned personal Psalters, | 0:49:59 | 0:50:03 | |

'because the Biblical ruler they feature, David, | 0:50:03 | 0:50:07 | |

'was seen as a model of kingship. | 0:50:07 | 0:50:09 | |

'Following tradition, | 0:50:09 | 0:50:10 | |

'King David is depicted in various scenes from the psalms. | 0:50:10 | 0:50:15 | |

'Whenever he turns up in this Psalter, however, | 0:50:15 | 0:50:18 | |

'he's a dead ringer for another monarch. | 0:50:18 | 0:50:22 | |

'You could argue that Henry VIII is being encouraged | 0:50:22 | 0:50:25 | |

'to see the relevance of Biblical teachings for his own life.' | 0:50:25 | 0:50:29 | |

Or you could say Henry is a megalomaniac. | 0:50:29 | 0:50:33 | |

Not only has he made himself head of the Church, | 0:50:33 | 0:50:37 | |

he's now imagining himself as the most important Biblical King. | 0:50:37 | 0:50:41 | |

'It's a very literal reading of the Bible, | 0:50:44 | 0:50:46 | |

'as if it had all been written about 16th-century England. | 0:50:46 | 0:50:50 | |

'So, when the psalmist warns, "The fool says in his heart, | 0:50:50 | 0:50:54 | |

'"There is no God," | 0:50:54 | 0:50:55 | |

'we see a portrait of Henry's fool, the Tudor court jester Will Somers. | 0:50:55 | 0:51:00 | |

'Everywhere the King looked, he'd see himself reflected back.' | 0:51:01 | 0:51:07 | |

For me, this is an intensely intimate scene | 0:51:07 | 0:51:11 | |

of one man alone with his books. | 0:51:11 | 0:51:13 | |

Henry has had himself inserted into this sacred text. | 0:51:13 | 0:51:18 | |

And here he is, reading the same text | 0:51:18 | 0:51:21 | |

and meditating on himself within the book. | 0:51:21 | 0:51:25 | |

'It must have felt like being in a hall of mirrors. | 0:51:27 | 0:51:30 | |

'And the self-references continue in the margins, | 0:51:31 | 0:51:35 | |

'where Henry's written a running commentary.' | 0:51:35 | 0:51:38 | |

Next to the opening psalm, which begins, | 0:51:39 | 0:51:42 | |

"Blessed is the man who has not walked | 0:51:42 | 0:51:44 | |

"in the counsel of the ungodly," | 0:51:44 | 0:51:46 | |

Henry has written, in his own hand, "Nota quis sit beatus." | 0:51:46 | 0:51:51 | |

"Note who is blessed." | 0:51:51 | 0:51:53 | |

And in a book full of images of Henry himself, | 0:51:53 | 0:51:56 | |

the implication is that it's HE who is blessed. | 0:51:56 | 0:52:00 | |

'Throughout the book, | 0:52:00 | 0:52:03 | |

'Henry's notes reveal a man convinced he was serving God's will, | 0:52:03 | 0:52:07 | |

'his confidence undimmed by his rejection of the Catholic Church. | 0:52:07 | 0:52:11 | |

'But there's one moment where the self-justification | 0:52:11 | 0:52:15 | |

'gives way to a note of frailty.' | 0:52:15 | 0:52:17 | |

In the margins of Psalm 36, where it says, "I have been young, | 0:52:19 | 0:52:23 | |

"and now I am old," Henry has written, | 0:52:23 | 0:52:26 | |

"Dolens dictum." | 0:52:26 | 0:52:28 | |

"A sad saying." | 0:52:28 | 0:52:30 | |

And so we get this glimpse into how Henry viewed his own mortality. | 0:52:30 | 0:52:36 | |

This is such a strange experience for me. | 0:52:38 | 0:52:41 | |

I'm touching the very pages that Henry VIII himself touched, | 0:52:41 | 0:52:47 | |

and he didn't just read this book, he read it again and again, | 0:52:47 | 0:52:51 | |

and he invested part of himself in it. | 0:52:51 | 0:52:54 | |

More than any other manuscript I've encountered, | 0:52:54 | 0:52:57 | |

I really get a sense of the real man coming out of these pages. | 0:52:57 | 0:53:01 | |

'The earliest English royal books had told a different story. | 0:53:04 | 0:53:09 | |

'Manuscripts in Anglo-Saxon times were largely public objects, | 0:53:09 | 0:53:13 | |

'displayed on altars. | 0:53:13 | 0:53:15 | |

'Their power came from the Church, as did the King's. | 0:53:16 | 0:53:19 | |

'Six centuries later, | 0:53:21 | 0:53:23 | |

'the King controls the institution his predecessors had depended upon. | 0:53:23 | 0:53:28 | |

'He now relies on no-one else in his relationship with God or England. | 0:53:28 | 0:53:33 | |

'So he's shown alone, in a book for his private use. | 0:53:33 | 0:53:37 | |

'For the English royal manuscript, | 0:53:37 | 0:53:39 | |

'it was pretty much the end of the line. | 0:53:39 | 0:53:42 | |

'By the later 16th century, changes in technology, in fashion and in art | 0:53:43 | 0:53:49 | |

'meant the manuscript was finally displaced by the printed book. | 0:53:49 | 0:53:54 | |

'Even among royalty.' | 0:53:54 | 0:53:56 | |

But the illuminated manuscript had a clear descendant | 0:53:58 | 0:54:01 | |

as a royal art form. | 0:54:01 | 0:54:03 | |

Something else that would continue the work | 0:54:03 | 0:54:05 | |

the manuscript had done for centuries, | 0:54:05 | 0:54:08 | |

and that could communicate and symbolise the King's power. | 0:54:08 | 0:54:11 | |

The royal portrait. | 0:54:12 | 0:54:15 | |

'When production of the illuminated manuscript was declining, | 0:54:21 | 0:54:25 | |

'in the 15th and 16th centuries, | 0:54:25 | 0:54:27 | |

'the painted portrait had become more popular, | 0:54:27 | 0:54:30 | |

'and the medium of choice for some of the greatest Renaissance artists. | 0:54:30 | 0:54:36 | |

'It would prove particularly suitable | 0:54:36 | 0:54:39 | |

'for the new challenges faced by England's monarchy.' | 0:54:39 | 0:54:43 | |

Now the King is the head of the Church, he had to be more visible | 0:54:43 | 0:54:47 | |

to the nation, not just a figurehead tucked away in his palaces. | 0:54:47 | 0:54:51 | |

While printing was the best way of spreading the royal word, | 0:54:51 | 0:54:54 | |

the portrait was perfect for disseminating the royal image. | 0:54:54 | 0:54:59 | |

'Take, for example, Hans Holbein's iconic picture of Henry VIII, | 0:54:59 | 0:55:04 | |

'for which this was the preparatory sketch.' | 0:55:04 | 0:55:08 | |

Even as an outline, you can tell who this is, | 0:55:08 | 0:55:11 | |

and that's entirely deliberate. | 0:55:11 | 0:55:13 | |

This is powerful propaganda. | 0:55:13 | 0:55:16 | |

'Portraits were intended to be seen by a wider public than | 0:55:17 | 0:55:21 | |

'the select few who would glimpse the pages of a royal manuscript. | 0:55:21 | 0:55:25 | |

'And the production of authorised copies could make the monarch | 0:55:25 | 0:55:29 | |

'more visible across their kingdom.' | 0:55:29 | 0:55:32 | |

The large-scale royal portrait might seem a world away | 0:55:32 | 0:55:35 | |

from the miniatures of illuminated manuscripts, | 0:55:35 | 0:55:38 | |

but early in his career, Holbein worked in book design, | 0:55:38 | 0:55:41 | |

and he wasn't alone either. | 0:55:41 | 0:55:42 | |

Other portraitists drew inspiration from the traditions of manuscripts. | 0:55:42 | 0:55:48 | |

'Some portraits were still painted on vellum, | 0:55:49 | 0:55:52 | |

'such as this one of Elizabeth I. | 0:55:52 | 0:55:54 | |

'It's the work of Nicholas Hilliard, | 0:55:54 | 0:55:57 | |

'who was most likely trained by a descendant of a Bruges illuminator. | 0:55:57 | 0:56:02 | |

'And it's only a couple of inches high, | 0:56:02 | 0:56:05 | |

'the small scale used for centuries in manuscripts. | 0:56:05 | 0:56:09 | |

'Portraiture could also draw on a well-established language | 0:56:13 | 0:56:17 | |

'for depicting royal power. | 0:56:17 | 0:56:18 | |

'The iconography of monarchy, which feels so familiar | 0:56:20 | 0:56:24 | |

'when we see portraits such as these, had first been developed | 0:56:24 | 0:56:27 | |

'in the pages of books. | 0:56:27 | 0:56:29 | |

'And that's not the manuscript's only legacy. | 0:56:32 | 0:56:36 | |

'Objects which had seemed redundant after the invention of printing | 0:56:38 | 0:56:42 | |

'have a renewed value now when the dominance of the printed book | 0:56:42 | 0:56:47 | |

'is in turn being challenged.' | 0:56:47 | 0:56:49 | |

We live in a world where, thanks to the digital revolution, | 0:56:52 | 0:56:56 | |

ideas and images can be shared across the globe in an instant. | 0:56:56 | 0:57:00 | |

Many millions of people can share the same things at the same time. | 0:57:00 | 0:57:04 | |

And this is of course incredibly powerful. | 0:57:04 | 0:57:06 | |

An illuminated manuscript was almost the exact opposite. | 0:57:06 | 0:57:10 | |

It was designed to be seen by just a handful of people | 0:57:10 | 0:57:14 | |

as an entirely bespoke artefact. | 0:57:14 | 0:57:17 | |

And from this exclusivity and uniqueness came its power. | 0:57:17 | 0:57:21 | |

'Precisely because they were never mass-produced, | 0:57:27 | 0:57:32 | |

'manuscripts have a specific historical weight and meaning, | 0:57:32 | 0:57:35 | |

'which it's hard to imagine being equalled | 0:57:35 | 0:57:37 | |

'by the sophisticated technology of today.' | 0:57:37 | 0:57:39 | |

'It's not just that they so beautifully picture that past, | 0:57:47 | 0:57:51 | |

'its religious fervour and its political manoeuvring, | 0:57:51 | 0:57:55 | |

'it's that they do so in such a tangible form. | 0:57:55 | 0:57:57 | |

'In an object that exists now in the same way as it did then.' | 0:57:57 | 0:58:04 | |

The thing that's really struck me about handling these manuscripts | 0:58:04 | 0:58:09 | |

is the intimacy of the experience. | 0:58:09 | 0:58:11 | |

By turning the pages, I feel as if I've sat down | 0:58:11 | 0:58:14 | |

next to their royal owners | 0:58:14 | 0:58:15 | |

and read over their shoulder, sharing in their insights. | 0:58:15 | 0:58:19 | |

These magnificent objects were once created | 0:58:19 | 0:58:22 | |

as pieces of propaganda or patronage, but now they offer us | 0:58:22 | 0:58:26 | |

a unique insight into the private lives of long dead kings. | 0:58:26 | 0:58:32 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:58:36 | 0:58:39 | |

E-mail [email protected] | 0:58:39 | 0:58:41 |