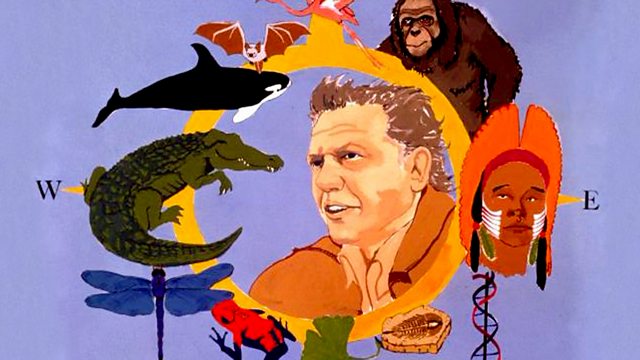

The Infinite Variety Life on Earth

Similar Content

Browse content similar to The Infinite Variety. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

There are some four million kinds of animals and plants. | 0:00:49 | 0:00:53 | |

Four million different solutions to the problems of staying alive. | 0:00:53 | 0:00:58 | |

This is the story of how a few of them came to be as they are. | 0:00:58 | 0:01:03 | |

The South American rainforest - the richest assemblage of life in the world. | 0:01:46 | 0:01:52 | |

Those are Howler monkeys there are 50 kinds of monkeys in these forests. | 0:01:52 | 0:01:59 | |

Some of the most beautiful creatures here are hummingbirds - 54 kinds were found a few miles from here. | 0:01:59 | 0:02:07 | |

And over 300 have been found in South America. | 0:02:07 | 0:02:11 | |

Nobody knows how many kinds of animal there are here - wherever you look, there's life. | 0:02:11 | 0:02:18 | |

There are several 100,000 different insects that have been named, | 0:02:31 | 0:02:36 | |

and, no doubt, hundreds more that haven't. | 0:02:36 | 0:02:40 | |

All these varied creatures and plants form one complex mosaic. | 0:02:40 | 0:02:44 | |

The orchid needs the bee to pollinate it. | 0:02:51 | 0:02:55 | |

The anteater couldn't have existed before the ants. | 0:02:55 | 0:03:00 | |

So unless the whole complex came into being in one flash of creation, | 0:03:00 | 0:03:05 | |

different organisms must have appeared at different times. | 0:03:05 | 0:03:10 | |

Which came first? And why such variety? | 0:03:10 | 0:03:13 | |

Such questions obsessed a 24-year-old Englishman who came to these forests in 1832. | 0:03:13 | 0:03:21 | |

He was Charles Darwin and he was enthralled - ecstatic - by the richness of life he found. | 0:03:21 | 0:03:29 | |

In one day, in a small area, he discovered 69 different species of beetle. | 0:03:29 | 0:03:37 | |

As he wrote in his journal, | 0:03:38 | 0:03:40 | |

"It's enough to disturb an entomologist's mind, | 0:03:40 | 0:03:44 | |

"to contemplate the future dimension of a complete catalogue." | 0:03:44 | 0:03:49 | |

The conventional view of the time was that each and every species of animal and plant | 0:03:49 | 0:03:56 | |

had been individually created by God. | 0:03:56 | 0:04:00 | |

And Darwin was no atheist. | 0:04:00 | 0:04:02 | |

For three years, the Beagle sailed around South America | 0:04:06 | 0:04:10 | |

and up into the Pacific. | 0:04:10 | 0:04:13 | |

600 miles west of Ecuador, | 0:04:14 | 0:04:17 | |

they came to the lonely Galapagos Islands. | 0:04:17 | 0:04:21 | |

It was here that Darwin's doubts about the Creation re-awakened. | 0:04:40 | 0:04:45 | |

Everywhere Darwin found creatures resembling those on the mainland. | 0:05:00 | 0:05:06 | |

But nearly all were slightly different. | 0:05:09 | 0:05:13 | |

These were, without doubt, cormorants - | 0:05:13 | 0:05:17 | |

like those he'd seen flying along Brazilian rivers. | 0:05:17 | 0:05:22 | |

But here, their wings were so small and with such stunted feathers, | 0:05:22 | 0:05:26 | |

that the birds had lost their power of flight. | 0:05:26 | 0:05:31 | |

And these were clearly iguanas. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:35 | |

He'd seen them climbing trees and eating leaves. | 0:05:35 | 0:05:38 | |

But here on the Galapagos, where there was little vegetation, | 0:05:38 | 0:05:44 | |

iguanas fed on seaweed. And they were not the same - smaller, darker, | 0:05:44 | 0:05:50 | |

with long claws to keep a foothold in the crashing breakers. | 0:05:50 | 0:05:56 | |

They also had extraordinary habits - | 0:06:02 | 0:06:05 | |

swimming fearlessly out to sea and diving deep to graze on the seabed. | 0:06:05 | 0:06:10 | |

The Galapagos Islands got the name from the tortoises that lived here which sailors slaughtered for food. | 0:06:23 | 0:06:31 | |

These too, were obviously different from mainland tortoises. | 0:06:31 | 0:06:37 | |

They were many, many times bigger. | 0:06:37 | 0:06:40 | |

The Vice-Governor of the Islands told Darwin he could tell where a tortoise came from by its shape. | 0:06:40 | 0:06:48 | |

This, with a deep rounded shell is from a well-watered island and feeds from vegetation on the ground. | 0:06:52 | 0:07:00 | |

This has a peak to the front of its shell, so it can stretch its long neck upwards. | 0:07:05 | 0:07:11 | |

It comes from an arid island where they have to crane up to reach the food available. | 0:07:11 | 0:07:17 | |

His suspicion grew that species weren't fixed for ever. | 0:07:20 | 0:07:24 | |

Perhaps they came from common ancestors and had changed to suit their particular islands. | 0:07:24 | 0:07:31 | |

The differences that Darwin had noticed among these animals were all tiny. | 0:07:35 | 0:07:42 | |

But if they could develop, wasn't it possible over millions of years, | 0:07:42 | 0:07:47 | |

a series of such differences might add up to one revolutionary change? | 0:07:47 | 0:07:53 | |

Wasn't it possible that amphibians had developed water-tight skins and turned into reptiles? | 0:07:53 | 0:08:00 | |

Or that a reptile had developed feathery scales and become a bird? | 0:08:00 | 0:08:06 | |

Or that man himself might be descended from a group of tree-swinging apes? | 0:08:06 | 0:08:12 | |

The idea wasn't new - others had suggested that all life might have a common ancestry. | 0:08:13 | 0:08:21 | |

But Darwin went further and gave the idea more force by suggesting a mechanism | 0:08:21 | 0:08:27 | |

which might have brought it about - he called it "natural selection". | 0:08:26 | 0:08:32 | |

Put briefly, his argument was this, | 0:08:34 | 0:08:37 | |

individuals of some species aren't identical - | 0:08:37 | 0:08:41 | |

some tortoises have slightly longer necks than others. | 0:08:41 | 0:08:47 | |

In times of drought, they could reach leaves - and live, | 0:08:47 | 0:08:52 | |

while the shorter-necked ones die. | 0:08:52 | 0:08:55 | |

So those best fitted will transmit characteristics to their offspring. | 0:08:56 | 0:09:02 | |

Eventually, tortoises on arid islands will have longer necks. | 0:09:04 | 0:09:07 | |

So, one species will have given rise to another. | 0:09:09 | 0:09:14 | |

In these programmes, we'll survey the great variety produced by natural selection | 0:09:18 | 0:09:26 | |

and look at them, not as oddities, but as elements in the long story | 0:09:26 | 0:09:32 | |

that began 1,000 million years ago and is still continuing today. | 0:09:32 | 0:09:37 | |

Some creatures, mammals like these sealions, | 0:09:37 | 0:09:40 | |

and myself - mammals both - are recent arrivals on the scene. | 0:09:40 | 0:09:45 | |

Others - birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish - have been here long, longer than we have. | 0:09:45 | 0:09:53 | |

In places where conditions have remained unchanged over immense periods, | 0:09:53 | 0:09:59 | |

there are creatures resembling closely their ancestors - they can tell us a lot. | 0:09:59 | 0:10:06 | |

But to disentangle the story, we'll also have to look for evidence in the rocks. | 0:10:06 | 0:10:12 | |

Bodies fall to the bottom of seas and swamps and get entombed. | 0:10:20 | 0:10:26 | |

The sediment, after millions of years, turns to rock and these remains survive as fossils. | 0:10:28 | 0:10:36 | |

Since discovering radioactivity, scientists have developed ways of measuring the age of rocks. | 0:11:00 | 0:11:05 | |

There are simpler ways of establishing the age of rocks that anyone can use. | 0:11:13 | 0:11:19 | |

There's no more dramatic place to do so than the Grand Canyon in the American West. | 0:11:20 | 0:11:26 | |

The Colorado River, aided by wind and rain, has cut a section through the sandstone and limestone. | 0:11:39 | 0:11:46 | |

The layers lie undisturbed so obviously the lower ones were deposited before the upper ones. | 0:11:48 | 0:11:55 | |

So if we want to trace the ancestory of life back to its beginnings, | 0:11:55 | 0:12:00 | |

we must go deeper into the canyon. | 0:12:00 | 0:12:02 | |

This is the greatest gash in the earth - from rim to bottom is a vertical mile. | 0:12:16 | 0:12:24 | |

There are many trails down and the usual way is on the back of a mule. | 0:12:24 | 0:12:30 | |

Here we're 500 feet from the lip of the canyon and the rocks are 200 million years old. | 0:13:12 | 0:13:20 | |

There are no mammal fossils but there are four-legged animals - small reptiles. | 0:13:20 | 0:13:28 | |

A lizard-like creature that left tracks here which was once the face of a sand-dune. | 0:13:28 | 0:13:36 | |

Farther down, no reptiles, but in limestone 400 million years old bones of armoured fish are found. | 0:13:50 | 0:13:59 | |

The trail winds on through rocks formed in ancient seas - and every 20 feet is another million years. | 0:14:06 | 0:14:16 | |

The Grand Canyon is really two canyons - one inside the other. | 0:14:28 | 0:14:33 | |

For a while, the trail flattens out as it approaches the rim of the inner canyon. | 0:14:33 | 0:14:39 | |

Here, I'm two-thirds the way down - 3,500 feet below the rim and the rocks are 500 million years old. | 0:14:42 | 0:14:53 | |

The rock has no backboned animals at all - no fish - the only ones are those without backbones, | 0:14:53 | 0:15:03 | |

including worms which left this tracery of trails. | 0:15:03 | 0:15:08 | |

At last, the bottom and the Colorado River - it's taken a day to get this far. | 0:15:33 | 0:15:42 | |

We've ridden 7 miles of trail and have descended that vertical mile into the earth's crust. | 0:15:42 | 0:15:49 | |

The rocks here are nearly 2,000 million years old. | 0:15:52 | 0:15:58 | |

For the past 800 feet, they've had no sign of fossils at all. | 0:15:58 | 0:16:05 | |

For years it was thought that all rocks of this great age had no fossils. | 0:16:05 | 0:16:11 | |

Why was this? Was it because they were so old they'd had all traces of life crushed from them? | 0:16:11 | 0:16:18 | |

Or did life really begin with creatures as big as a worm? For years this was a great puzzle. | 0:16:18 | 0:16:26 | |

Then 20 years ago, people realised they'd been looking in the wrong rocks and in the wrong way. | 0:16:26 | 0:16:33 | |

These are the right rocks - a kind of flint called chert - at Lake Superior in Canada. | 0:16:41 | 0:16:49 | |

It's 1,000 miles east and north of the Grand Canyon. | 0:16:49 | 0:16:54 | |

They were well known in the last century - pioneers used them in their flintlock guns. | 0:16:54 | 0:17:01 | |

Scientists have recognised for a long time they were extremely ancient rocks. | 0:17:01 | 0:17:07 | |

We now know they're the same age as those in the bottom of the Grand Canyon - 2,000 million years. | 0:17:07 | 0:17:16 | |

But- these strange rings in them - these were a subject of great controversy. | 0:17:16 | 0:17:25 | |

Some maintained they were a sign of very early life. | 0:17:25 | 0:17:31 | |

Others said they were ordinary chemical processes in the rock's formation. | 0:17:31 | 0:17:38 | |

Then, in the 1950s, scientists started looking at them in the right way. | 0:17:38 | 0:17:43 | |

First you cut a wafer-thin slice. | 0:17:52 | 0:17:56 | |

This is ground down for several hours. | 0:17:58 | 0:18:02 | |

When scientists first prepared chert to look at through the microscope, | 0:18:10 | 0:18:16 | |

many people doubted that primitive forms of life could possibly be preserved as tiny fossils. | 0:18:16 | 0:18:23 | |

Then scientists saw this. | 0:18:26 | 0:18:28 | |

Marks in rock can be deceptive - they may be the result of mineral action. | 0:18:31 | 0:18:37 | |

But these filaments are almost identical to algae growing today. | 0:18:37 | 0:18:42 | |

Soon fossils of other primitive life were found, that once lived in those early seas. | 0:18:51 | 0:18:57 | |

Other micro-fossils have been found - | 0:19:04 | 0:19:08 | |

in rocks even older - 3,000 million years old. | 0:19:08 | 0:19:14 | |

These immense periods baffle the imagination, but we get an idea of relative lengths of the stages, | 0:19:14 | 0:19:24 | |

if we condense the history of life on earth into one year - then 10 million years become one day. | 0:19:24 | 0:19:33 | |

On that calendar, I talk in the last moment of Dec 31, man arrived a few hours ago in the afternoon. | 0:19:33 | 0:19:45 | |

The first backboned animal crawled on to land in the last week of November, | 0:19:45 | 0:19:51 | |

and these gunflint cherts were formed on June 15th. | 0:19:51 | 0:19:57 | |

Now let's go back, way, way, to the beginning of January, to the beginning of life. | 0:19:57 | 0:20:05 | |

3500 million years ago, our planet was very different from the one we live on today. | 0:20:14 | 0:20:20 | |

Erupting volcanoes built islands of lava and ash in the seas. | 0:20:24 | 0:20:29 | |

The atmosphere was filled with gases, such as ammonia, methane, hydrogen and steam. | 0:20:29 | 0:20:36 | |

There was no oxygen - so consequently there was no ozone, | 0:20:45 | 0:20:51 | |

so ultra-violet rays bathed the young planet. | 0:20:51 | 0:20:55 | |

Carbon compounds formed including amino acids - the building blocks of protein. | 0:21:34 | 0:21:40 | |

For millions of years, the chemical soup thickened and changed, possibly added to from outer space. | 0:21:45 | 0:21:52 | |

Some compounds aggregated in droplets, with a membrane through which other chemicals could pass. | 0:21:56 | 0:22:02 | |

Eventually, large molecules appeared with extraordinary characteristics. | 0:22:13 | 0:22:19 | |

They caused amino acids to form round them and so built proteins but also produced copies of themselves. | 0:22:19 | 0:22:26 | |

Such a molecule - DNA - is at the centre of every life cell. | 0:22:28 | 0:22:33 | |

Its shape is a double spiral linked by chemical units of four kinds. | 0:22:33 | 0:22:39 | |

Their arrangement acts as a code for production of protein and a group in DNA is called a gene. | 0:22:39 | 0:22:46 | |

On occasion, the DNA unzips and each half attracts the correct chemical units and forms two new molecules. | 0:22:49 | 0:22:58 | |

When this first happened, primitive cells formed new cells and life on earth had appeared. | 0:22:58 | 0:23:05 | |

Sometimes a mistake can cause variations in first cells and natural selection sorted them out. | 0:23:08 | 0:23:18 | |

Those best suited to their environment survived - the rest died. | 0:23:20 | 0:23:26 | |

So, over tens of millions of years, new organisms developed and invaded new environments on earth. | 0:23:35 | 0:23:45 | |

Evolution had truly begun. | 0:23:49 | 0:23:52 | |

We can glimpse what early life was like, in the hot springs of Yellowstone Park in Wyoming. | 0:24:03 | 0:24:11 | |

These springs are stained a variety of colour | 0:24:19 | 0:24:24 | |

by micro-organisms that look to be identical with some of the earliest fossils that we know. | 0:24:24 | 0:24:31 | |

Tufts of bacteria grow where the water's hottest. | 0:24:33 | 0:24:37 | |

In cooler areas, other bacteria deposit silica, in strange coloured crusts. | 0:24:40 | 0:24:47 | |

They represent the next big step. | 0:24:50 | 0:24:53 | |

They're probably like the first forms to manufacture food | 0:24:54 | 0:24:58 | |

inside their cell walls, with the aid of energy from the sun - light. | 0:24:58 | 0:25:04 | |

One of the raw materials needed was hydrogen and at first they got it as sulphuretted hydrogen. | 0:25:06 | 0:25:12 | |

It occurs in volcanic gases - there's some around here - it smells a bit of rotten eggs. | 0:25:12 | 0:25:20 | |

And indeed, there's such bacteria flourishing in the hot water of these springs. | 0:25:20 | 0:25:26 | |

Then that link with volcanoes was broken and forms of bacteria arose which got their hydrogen | 0:25:26 | 0:25:33 | |

from a more widespread and easily available source - from water and it was a crucial stage in life. | 0:25:33 | 0:25:41 | |

Because if you take hydrogen from water, you're left as a by-product with oxygen. | 0:25:41 | 0:25:48 | |

These new bacteria still exist | 0:25:58 | 0:26:01 | |

as slime on rocks or in ponds covered with silver bubbles. | 0:26:01 | 0:26:05 | |

It was they that first contributed oxygen to the atmosphere. | 0:26:05 | 0:26:10 | |

Under the microscope, they're seen as very simple structures. | 0:26:11 | 0:26:16 | |

Some form chains - others isolated beads. | 0:26:18 | 0:26:23 | |

On a larger scale, they form mats of bacteria in the cooler springs of Yellowstone. | 0:26:29 | 0:26:36 | |

Some of these bluegreens deposit lime as part of the chemistry of their body processes. | 0:26:42 | 0:26:48 | |

In one place in the world - a bay off Western Australia, they grow huge and form these pillars. | 0:26:48 | 0:26:58 | |

What makes this special, is the mouth of the bay is almost blocked by a bar of sand and sea grass. | 0:26:59 | 0:27:07 | |

This restricts the flow of the tide in and out, with a result that these waters are extremely salty. | 0:27:07 | 0:27:15 | |

Virtually none of the creatures which eat bluegreens can survive here. | 0:27:15 | 0:27:21 | |

So the bluegreens, primitive organisms, can grow uncropped, | 0:27:21 | 0:27:26 | |

as when they were an advanced form of life 2000 million years ago, at the beginning of life on earth. | 0:27:26 | 0:27:36 | |

Here is an explanation for the shapes we saw on the shores of Lake Superior. | 0:27:36 | 0:27:42 | |

This is as close as we may get to a scene of the world when life was at last beginning to stir. | 0:28:11 | 0:28:18 | |

Now life had reached the point of no return - the oxygen accumulated and formed ozone in the atmosphere. | 0:28:23 | 0:28:30 | |

It screened off ultra-violet rays that had helped create life. | 0:28:30 | 0:28:34 | |

It could never begin in the same way again. | 0:28:36 | 0:28:41 | |

Things changed little for millions of years but at last came a new and dramatic step. | 0:28:46 | 0:28:55 | |

To find evidence of that development, you need go no further than your local pond. | 0:28:57 | 0:29:04 | |

Most microscopic organisms here are single cells, yet each is much more complex than any bacterium. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:29 | |

Some, like this amoeba, seem to have animal characteristics. | 0:29:32 | 0:29:37 | |

Some appear to be simple plants. | 0:29:37 | 0:29:40 | |

Yet others seem to be half animal, half plant. | 0:29:41 | 0:29:45 | |

Seen through an electron-microscope, | 0:29:52 | 0:29:57 | |

the DNA is enclosed in its own compartment - other parts resemble and act like, bluegreens. | 0:29:57 | 0:30:06 | |

They look more like bacteria and are a source of energy. | 0:30:09 | 0:30:14 | |

This cell's driven by a tail that resembles another bacterium. | 0:30:18 | 0:30:24 | |

So, it appears, this tiny creature is composed of a committee of smaller ones. | 0:30:24 | 0:30:29 | |

It took a long time for life to reach this stage. | 0:30:41 | 0:30:46 | |

Probably not till 1,200 million years ago - say early September in our life-on-earth year. | 0:30:46 | 0:30:52 | |

These belong to this advanced type - many still abound in fresh water and the sea. | 0:31:00 | 0:31:05 | |

They form the basic food of other organisms. | 0:31:05 | 0:31:10 | |

Some have skeletons of silica. | 0:31:40 | 0:31:43 | |

Another kind with shell of chalk. | 0:31:57 | 0:32:00 | |

They're like an amoeba to which they're closely related. | 0:32:08 | 0:32:12 | |

Food is drawn inside. | 0:32:17 | 0:32:21 | |

They reproduce by splitting in two. | 0:32:29 | 0:32:32 | |

Some cells have more complicated methods of reproduction. | 0:32:39 | 0:32:44 | |

These have temporarily joined to exchange genes - later they'll part and divide in the normal way. | 0:32:45 | 0:32:53 | |

Others shuffle genes and divide so as to produce a special cell with half the genes of the parent - | 0:33:01 | 0:33:09 | |

these special cells are eggs. | 0:33:09 | 0:33:13 | |

Others of the species also produce sex cells. | 0:33:20 | 0:33:24 | |

This time they're quite different in form - they have tails - they're sperm cells. | 0:33:25 | 0:33:32 | |

They're attracted to the egg. | 0:33:37 | 0:33:39 | |

The first to find it, penetrates it. | 0:33:40 | 0:33:44 | |

It swims to the nucleus and unites with it - so the full complement of genes is restored. | 0:33:49 | 0:33:55 | |

But now it's in a new combination, different from either parent. | 0:33:55 | 0:34:00 | |

When this developed, the extent and frequency of variation increased. | 0:34:01 | 0:34:07 | |

The pace of evolution accelerated. | 0:34:10 | 0:34:15 | |

One of the most successful groups are the ciliates. | 0:34:21 | 0:34:25 | |

They're covered with hairs, cilia, which drive them through the water. | 0:34:25 | 0:34:31 | |

They also create currents which waft food into their gullet. | 0:34:31 | 0:34:37 | |

These ciliates are stalked and anchored to one spot. | 0:35:00 | 0:35:04 | |

Others are large and mobile and hunt for their food. | 0:35:05 | 0:35:09 | |

These ciliates are quite large. | 0:35:21 | 0:35:23 | |

Just visible to the naked eye. | 0:35:24 | 0:35:27 | |

But size can be got in another way. | 0:35:33 | 0:35:36 | |

By grouping cells together in an organised colony. | 0:35:37 | 0:35:41 | |

This, the size of a pinhead, has hundreds of cells with tails, beating in a co-ordinated way. | 0:35:43 | 0:35:52 | |

Inside, daughter colonies are formed and the delicate globe ruptures to release them. | 0:35:58 | 0:36:04 | |

A stage further - and sponges appeared. | 0:36:13 | 0:36:17 | |

There are 5,000 species of sponges today and their bonds are very loose. | 0:36:24 | 0:36:32 | |

Individual cells may crawl around the surface like amoeba. | 0:36:32 | 0:36:38 | |

If a sponge is forced through a sieve, so it breaks into separate cells, | 0:36:38 | 0:36:43 | |

they'll reorganise to form a new sponge. | 0:36:43 | 0:36:46 | |

What's more, each cell will take its proper place. | 0:36:48 | 0:36:52 | |

Some form walls, others are pump cells lining channels with which the sponge is riddled. | 0:36:54 | 0:37:01 | |

By beating their threads, they draw in water through pores on the sides. | 0:37:03 | 0:37:09 | |

Then pump it out at the top after the food has been strained off. | 0:37:09 | 0:37:14 | |

The structure's supported by other cells which make tiny needles to form a skeleton. | 0:37:16 | 0:37:22 | |

In glass sponges, they're made of silica. | 0:37:23 | 0:37:27 | |

Modern science is only 300 years old, yet it's provided us with profound insights | 0:37:31 | 0:37:39 | |

into the workings of the world, but there's a lot we don't know - take this sponge skeleton. | 0:37:39 | 0:37:46 | |

How on earth did the tiny sponge cells collaborate to build from millions of splinters of silica | 0:37:48 | 0:38:01 | |

this complex, beautiful structure - Venus's Flower-basket? | 0:38:01 | 0:38:06 | |

Some religious people say it's the work of God and that's all that need be said. | 0:38:08 | 0:38:14 | |

Some scientists claim that in time we'll provide a more detailed explanation than that. | 0:38:14 | 0:38:21 | |

Either way, it's an awesome and beautiful object. | 0:38:21 | 0:38:25 | |

But sponges are a dead end. | 0:38:26 | 0:38:30 | |

They have no mouth, no gut, no muscles, no nervous system. | 0:38:30 | 0:38:35 | |

But this has. | 0:38:35 | 0:38:38 | |

It's a jelly-like creature - just 2 layers of cells - the inner one lines a cavity with an opening. | 0:38:42 | 0:38:50 | |

It's a fully co-ordinated, multi-celled animal. | 0:38:53 | 0:38:57 | |

It's one of several comb jellies which swarm in the ocean. | 0:38:57 | 0:39:01 | |

So transparent they're hardly noticed. | 0:39:01 | 0:39:05 | |

To appreciate their full beauty, you must use special lighting. | 0:39:14 | 0:39:18 | |

A Medusa - after the lady in the Greek myth who had snakes on her head for hair. | 0:40:18 | 0:40:23 | |

Its tentacles have stings for prey. | 0:40:24 | 0:40:26 | |

Comb jellies and medusae have muscle fibres and a nervous system - and most medusae have a surprise. | 0:40:38 | 0:40:45 | |

They begin life differently. | 0:40:45 | 0:40:48 | |

They look like plants - but are animals. | 0:40:53 | 0:40:56 | |

Each began when a tiny creature developed from the egg of a medusae. | 0:40:57 | 0:41:01 | |

It settled on the bottom of the sea. | 0:41:02 | 0:41:05 | |

From it grew a twig bearing polyps. | 0:41:07 | 0:41:10 | |

Each polyp is a medusa and in some species the medusae bud off the branch and swim away. | 0:41:23 | 0:41:30 | |

Others are born from special vessels. | 0:41:30 | 0:41:33 | |

All these medusae, not much bigger than a pinhead, have been produced without sex. | 0:42:21 | 0:42:28 | |

Later, they develop sexual cells which are released into the sea to produce larvae for new polyps. | 0:42:28 | 0:42:36 | |

This alternation between sexual and non-sexual means of reproduction | 0:42:40 | 0:42:47 | |

has given these creatures great scope for variety. | 0:42:47 | 0:42:51 | |

The larger medusae carry jelly so they're more robust in rough seas - these are the true jellyfish. | 0:43:09 | 0:43:16 | |

Many lead the same type of double life, having a stationary polyp phase as well as a swimming one. | 0:43:17 | 0:43:24 | |

It's an obvious deduction that jellyfish appeared very early in the development of life. | 0:44:31 | 0:44:39 | |

But there was no proof they did - after all, proof could only come from the fossil record. | 0:44:39 | 0:44:46 | |

and how could such a thing as a jellyfish be fossilised, | 0:44:46 | 0:44:51 | |

let alone survive in rocks from the earliest period? Then, 30 years ago in these sandstones | 0:44:51 | 0:44:59 | |

in the Flinders Ranges, Australia - probably 650 million years old - people found things like this. | 0:44:59 | 0:45:09 | |

At first, many refused to believe these faint impressions were the remains of jellyfish. | 0:45:15 | 0:45:22 | |

But enough have been found to make quite sure that that's what they are. | 0:45:22 | 0:45:28 | |

This, a form of jellyfish, isn't a single creature, but a colony of polyps. | 0:45:58 | 0:46:03 | |

It has gone to sea and has much the same structure as a true jellyfish. | 0:46:04 | 0:46:09 | |

Another colony built the same way is the Portuguese man o' war. | 0:46:14 | 0:46:18 | |

It has no swimming bell, but a bag filled with gas that supports the colony. | 0:46:19 | 0:46:26 | |

Tentacles trail behind for up to 50 metres. | 0:46:37 | 0:46:41 | |

The colony begins with one member which buds off. | 0:46:47 | 0:46:52 | |

These, bud off others - some for feeding, some for reproduction, some to catch prey. | 0:46:54 | 0:47:00 | |

As with all jellyfish and their relatives, the tentacles have special stinging cells. | 0:47:02 | 0:47:07 | |

Each has a coiled tube which discharges on contact with prey. | 0:47:07 | 0:47:13 | |

These are complicated creatures and you'd think, recent developments. | 0:47:26 | 0:47:31 | |

In fact, a fossil from the Flinders Range, suggest they existed 650 million years ago. | 0:47:31 | 0:47:37 | |

Alongside these jellyfish in the same rocks, are remains of other related creatures. | 0:48:05 | 0:48:12 | |

These were animals in which a kind of medusa remained small, and joined to form a colony. | 0:48:14 | 0:48:22 | |

We can be sure of that, because similar creatures are alive today, only 40 miles from here in the sea. | 0:48:22 | 0:48:33 | |

Sea pens - on either side of the stems are polyps for feeding and reproduction. | 0:48:37 | 0:48:44 | |

It bears a remarkable resemblance to the fossil. | 0:48:45 | 0:48:49 | |

These are soft corals. | 0:49:12 | 0:49:15 | |

Another kind - dead man's fingers. | 0:49:16 | 0:49:20 | |

Soft corals of all kinds grow in depths of 6,000 metres. | 0:49:25 | 0:49:31 | |

Stony corals make limestone reefs. | 0:49:32 | 0:49:35 | |

They live no deeper than 40 metres. | 0:49:36 | 0:49:39 | |

Cells grow over early ones and stifle them. | 0:49:59 | 0:50:02 | |

The corals contain plants. | 0:50:08 | 0:50:11 | |

Tiny, single-celled green algae. | 0:50:11 | 0:50:14 | |

Like all plants they release oxygen. | 0:50:15 | 0:50:19 | |

They also assimilate carbon dioxide and that helps the corals to form their skeletons of lime. | 0:50:20 | 0:50:26 | |

The reef may look like some fantastic, multi-coloured jungle of plants and flowers. | 0:51:27 | 0:51:33 | |

But when you touch one, it has the hard, incongruous scratch of stone. | 0:51:33 | 0:51:40 | |

Coral organisms are tiny and simple, yet grow on such a scale and their skeletons are so durable | 0:52:06 | 0:52:14 | |

that they may well have been the first signs of life that could be detected from outer space. | 0:52:14 | 0:52:21 | |

Certainly this Great Barrier Reef can be seen from the moon. | 0:52:21 | 0:52:25 | |

So it may be if an astronaut came this way, several hundreds of millions of years ago, | 0:52:25 | 0:52:32 | |

he might have noticed, in the seas of the earth, a few mysterious and beautiful shapes in turquoise, | 0:52:32 | 0:52:40 | |

and guessed that life on earth had really started. | 0:52:40 | 0:52:44 | |

Subtitles by Bill Northwood - 1982 | 0:54:00 | 0:54:03 |