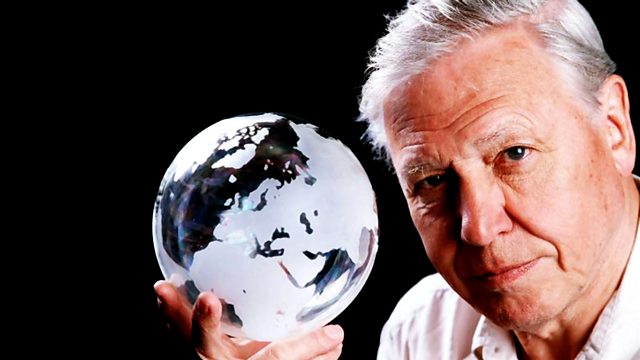

Introduction The Blue Planet

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Introduction. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Dwarfed by the vast expanse of the open ocean, | 0:00:31 | 0:00:36 | |

the biggest animal that has ever lived on our planet. | 0:00:36 | 0:00:41 | |

A blue whale, 30m long and weighing over 200 tonnes. | 0:00:46 | 0:00:51 | |

It's far bigger than even the biggest dinosaur. | 0:00:51 | 0:00:56 | |

Its tongue weighs as much as an elephant, | 0:00:56 | 0:01:00 | |

its heart is the size of a car | 0:01:00 | 0:01:02 | |

and some of its blood vessels are so wide you could swim down them. | 0:01:02 | 0:01:07 | |

Its tail alone is the width of a small aircraft's wings. | 0:01:08 | 0:01:13 | |

Its streamlining, close to perfection, | 0:01:29 | 0:01:34 | |

enables it to cruise at 20 knots. | 0:01:34 | 0:01:37 | |

It's one of the fastest animals in the sea. | 0:01:37 | 0:01:41 | |

The ocean's largest inhabitant | 0:01:43 | 0:01:46 | |

feeds almost exclusively on one of the smallest - | 0:01:46 | 0:01:50 | |

krill, a crustacean just a few centimetres long. | 0:01:50 | 0:01:55 | |

Gathered in a shoal, krill stain the sea red. | 0:01:57 | 0:02:01 | |

A single blue whale in a day can consume 40 million of them. | 0:02:01 | 0:02:05 | |

Despite the enormous size of blue whales | 0:02:14 | 0:02:17 | |

we know very little about them. | 0:02:17 | 0:02:20 | |

Their migration routes are still a mystery | 0:02:20 | 0:02:22 | |

and we have no idea where they go to breed. | 0:02:22 | 0:02:25 | |

They are a dramatic reminder of how much we still have to learn | 0:02:30 | 0:02:34 | |

about the ocean and the creatures that live there. | 0:02:34 | 0:02:39 | |

Our planet is a blue planet. | 0:02:40 | 0:02:43 | |

Over 70% of it is covered by the sea. | 0:02:43 | 0:02:46 | |

The Pacific Ocean alone covers half the globe. | 0:02:49 | 0:02:52 | |

You can fly across it for 12 hours | 0:02:52 | 0:02:55 | |

and still see nothing more than a speck of land. | 0:02:55 | 0:02:58 | |

This series will reveal the complete natural history of our ocean planet, | 0:03:00 | 0:03:05 | |

from its familiar shores to the mysteries of its deepest seas. | 0:03:05 | 0:03:09 | |

THEY SHRIEK | 0:03:11 | 0:03:14 | |

By volume, the ocean makes up 97% of the Earth's inhabitable space. | 0:03:20 | 0:03:26 | |

Its marine life far exceeds that which inhabits the land. | 0:03:26 | 0:03:32 | |

But life in the ocean is not evenly spread. | 0:03:54 | 0:03:57 | |

It's regulated by the path of currents carrying nutrients | 0:03:57 | 0:04:02 | |

and the varying power of the sun. | 0:04:02 | 0:04:04 | |

In this first programme we'll see how these two forces interact | 0:04:04 | 0:04:09 | |

to control life from the coral seas... | 0:04:09 | 0:04:13 | |

..to the polar wastes. | 0:04:14 | 0:04:17 | |

SEA LION ROARS | 0:04:36 | 0:04:40 | |

The sheer physical power of the ocean dominates our planet. | 0:05:09 | 0:05:14 | |

It profoundly influences the weather of all the world. | 0:05:30 | 0:05:35 | |

Water vapour rising from it forms the clouds | 0:05:35 | 0:05:39 | |

and generates the storms that ultimately will drench the land. | 0:05:39 | 0:05:44 | |

The great waves that roar in towards the shores | 0:05:59 | 0:06:04 | |

are dramatic demonstrations of its power. | 0:06:04 | 0:06:07 | |

Waves originate far out at sea. | 0:06:21 | 0:06:24 | |

There, even gentle breezes can cause ripples | 0:06:24 | 0:06:29 | |

and ripples grow into swells. | 0:06:29 | 0:06:32 | |

Out in the ocean, unimpeded by land, such swells can become gigantic. | 0:06:40 | 0:06:46 | |

It's only when an ocean swell eventually reaches shallow water | 0:07:07 | 0:07:12 | |

that it starts to break. | 0:07:12 | 0:07:14 | |

As it approaches the coast, | 0:07:19 | 0:07:22 | |

the bottom of the swell is slowed by contact with the sea bed. | 0:07:22 | 0:07:27 | |

The top of the swell, still going fast, starts to roll over | 0:07:27 | 0:07:32 | |

and so the wave breaks. | 0:07:32 | 0:07:35 | |

The ocean never rests. | 0:08:03 | 0:08:06 | |

Huge currents such as the Gulf Stream, | 0:08:06 | 0:08:10 | |

keep its waters on the move all round the globe. | 0:08:10 | 0:08:14 | |

These currents, more than any other factor, | 0:08:14 | 0:08:17 | |

control the distribution of nutrients and life in the seas. | 0:08:17 | 0:08:22 | |

A tiny island lost in the midst of the Pacific. | 0:08:22 | 0:08:27 | |

It's the tip of a huge mountain that rises from the sea floor below. | 0:08:27 | 0:08:33 | |

The nearest land is 300 miles away. | 0:08:38 | 0:08:42 | |

Isolated sea mounts like this one create oases | 0:08:45 | 0:08:49 | |

where life can flourish in the comparatively empty expanses of the open ocean. | 0:08:49 | 0:08:55 | |

But the creatures that swim beside it would not be here were it not for one key factor - | 0:09:03 | 0:09:10 | |

the deep ocean currents. | 0:09:10 | 0:09:13 | |

Far below the surface, | 0:09:17 | 0:09:19 | |

they collide with the island's flanks and are deflected upwards, | 0:09:19 | 0:09:24 | |

bringing from the depths, a rich soup of nutrients. | 0:09:24 | 0:09:28 | |

Such upwellings attract great concentrations of life. | 0:09:30 | 0:09:35 | |

Most of the fish here are permanent residents feeding on the plankton, | 0:09:42 | 0:09:47 | |

tiny plants and animals nourished by richness brought from the depths. | 0:09:47 | 0:09:52 | |

They in turn attract visitors from the open ocean. | 0:09:52 | 0:09:56 | |

Tuna. | 0:09:57 | 0:09:59 | |

The plankton feeders are easy targets. | 0:10:23 | 0:10:27 | |

All this action attracts even larger predators. | 0:10:37 | 0:10:41 | |

Sharks. | 0:10:44 | 0:10:46 | |

Hundreds of sharks. | 0:10:50 | 0:10:54 | |

These silky sharks are normally ocean-going species, | 0:10:54 | 0:10:58 | |

but the sea mounts in the eastern Pacific, | 0:10:58 | 0:11:01 | |

like Cocos, Malpelo and the Galapagos, | 0:11:01 | 0:11:04 | |

attract silkies in huge groups, up to 500 strong. | 0:11:04 | 0:11:08 | |

Silkies specialise in taking injured fish | 0:11:12 | 0:11:15 | |

and constantly circle sea mounts looking for the chance to do so. | 0:11:15 | 0:11:20 | |

But silkies are not the only visitors. | 0:11:24 | 0:11:28 | |

Hammerheads gather in some of the largest shark shoals to be found anywhere in the ocean. | 0:11:31 | 0:11:38 | |

Sometimes thousands will circle over a single sea mount. | 0:11:38 | 0:11:43 | |

But these sharks are not here for food. | 0:11:46 | 0:11:49 | |

They have come for another reason. | 0:11:49 | 0:11:52 | |

Some of the locals provide a cleaning service. | 0:11:55 | 0:12:00 | |

Following the last El Nino year, | 0:12:01 | 0:12:04 | |

when a rise in water temperatures caused many sharks to suffer from fungal infections, | 0:12:04 | 0:12:11 | |

the number of hammerheads at the sea mounts reached record levels. | 0:12:11 | 0:12:16 | |

Nutrients also well up to the surface along the coasts of the continents. | 0:12:23 | 0:12:30 | |

This is Natal on South Africa's eastern seaboard. | 0:12:30 | 0:12:35 | |

It's June, and just offshore | 0:12:35 | 0:12:37 | |

strange, black patches have appeared. | 0:12:37 | 0:12:40 | |

They look like immense oil slicks up to a mile long. | 0:12:44 | 0:12:49 | |

But this is a living slick - | 0:12:50 | 0:12:54 | |

millions of sardines on a marine migration | 0:12:54 | 0:12:58 | |

that in sheer biomass rivals that of the wildebeest on the grasslands of Africa. | 0:12:58 | 0:13:04 | |

Most of the time these fish live in the cold waters south of the Cape. | 0:13:06 | 0:13:11 | |

But each year, the coastal currents reverse. | 0:13:11 | 0:13:14 | |

The warm Agulhas current that flows from the north has been displaced | 0:13:14 | 0:13:19 | |

by cold water from the south and has brought up rich nutrients. | 0:13:19 | 0:13:23 | |

They in turn have created a bloom of plankton | 0:13:23 | 0:13:27 | |

and the sardines are now feasting on it. | 0:13:27 | 0:13:31 | |

As the sardines travel north, a caravan of predators follow them. | 0:13:40 | 0:13:45 | |

Thousands of Cape gannets track the sardines. | 0:13:47 | 0:13:51 | |

They nested off the Cape | 0:13:51 | 0:13:53 | |

and timed their breeding so their chicks can join them in pursuing the shoals. | 0:13:53 | 0:14:00 | |

Below water, hundreds of sharks have also joined the caravan. | 0:14:06 | 0:14:11 | |

These are bronze whaler sharks, | 0:14:13 | 0:14:16 | |

a cold-water species that normally lives much further south. | 0:14:16 | 0:14:19 | |

These three-metre sharks cut such swathes through the sardine shoals | 0:14:24 | 0:14:30 | |

that their tracks are clearly visible from the air. | 0:14:30 | 0:14:34 | |

Harried by packs of predators and swept in by the action of the waves, | 0:14:34 | 0:14:38 | |

the sardine shoals are penned close to the shore. | 0:14:38 | 0:14:42 | |

Common dolphin are coming in from the open ocean to join the feast. | 0:14:59 | 0:15:04 | |

There are over a thousand of them in this one school. | 0:15:16 | 0:15:21 | |

When they catch up with the sardines, the action really begins. | 0:15:30 | 0:15:35 | |

Working together, they drive the shoal towards the surface. | 0:15:39 | 0:15:44 | |

It's easier for the dolphins to snatch fish up here. | 0:15:51 | 0:15:55 | |

Now the sardines have no escape. | 0:16:09 | 0:16:13 | |

Thanks to the dolphins, the sardines have come within the diving range of the gannets. | 0:16:22 | 0:16:29 | |

Hundreds of white arrows shoot into the sea | 0:16:40 | 0:16:44 | |

leaving long trails of bubbles behind each dive. | 0:16:44 | 0:16:49 | |

Next to join the frenzy are the sharks. | 0:16:59 | 0:17:02 | |

Sharks get very excited around dolphins, | 0:17:14 | 0:17:17 | |

maybe because they can feed well, | 0:17:17 | 0:17:20 | |

once the dolphins drive the sardines into more compact groups near the surface. | 0:17:20 | 0:17:27 | |

As the frenzy continues, walls of bubbles drift upwards. | 0:17:28 | 0:17:33 | |

They are being released by the dolphins, working together in teams. | 0:17:35 | 0:17:40 | |

They use the bubbles to corral the sardines into ever tighter groups. | 0:17:43 | 0:17:48 | |

The sardines seldom cross the wall of bubbles | 0:17:51 | 0:17:54 | |

and crowd closer together. | 0:17:54 | 0:17:57 | |

Bubble netting enables the dolphins to grab every last trapped sardine. | 0:18:00 | 0:18:06 | |

Just when the feasting seems to be almost over, a Bryde's whale. | 0:18:17 | 0:18:22 | |

The survivors head on northwards | 0:18:26 | 0:18:29 | |

and the caravan of predators follows them. | 0:18:29 | 0:18:33 | |

Nutrients can also be brought up, though less predictably, by rough weather. | 0:18:39 | 0:18:46 | |

Particularly near the Poles, huge storms stir the depths | 0:18:49 | 0:18:54 | |

and enrich the surface waters. | 0:18:54 | 0:18:56 | |

And here in the south Atlantic, the seas are the roughest on the planet. | 0:18:56 | 0:19:01 | |

And very rich seas they are too. | 0:19:03 | 0:19:06 | |

The cold Falklands current from the south | 0:19:06 | 0:19:09 | |

meets the warm Brazil current from the north. | 0:19:09 | 0:19:12 | |

At their junction, there is food in abundance. | 0:19:12 | 0:19:16 | |

These black-browed albatross are diving for krill that has been driven up to the surface. | 0:19:16 | 0:19:24 | |

Like all albatross, black-brows are wanderers across the open ocean. | 0:19:28 | 0:19:33 | |

A feeding assembly on this scale is a rare sight. | 0:19:46 | 0:19:51 | |

Usually, the birds of the open sea are widely dispersed. | 0:19:51 | 0:19:55 | |

But these feeding grounds are close to an albatross breeding colony, | 0:19:55 | 0:20:00 | |

and a very special one. | 0:20:00 | 0:20:02 | |

This is Steeple Jason, a remote island in the west of the Falklands. | 0:20:11 | 0:20:16 | |

It has the largest albatross colony in the world. | 0:20:16 | 0:20:20 | |

There are almost half a million albatross here, | 0:20:27 | 0:20:31 | |

an astonishing demonstration of how fertile the ocean can be | 0:20:31 | 0:20:36 | |

and how much food it can give even to creatures that don't live in it. | 0:20:36 | 0:20:41 | |

LOUD CAWING OF BIRDS | 0:20:54 | 0:20:58 | |

Not only nutrients generate these vast assemblies. | 0:21:07 | 0:21:11 | |

The heat and light that the sun brings | 0:21:11 | 0:21:14 | |

is essential for the growth of microscopic floating plants, | 0:21:14 | 0:21:19 | |

the phytoplankton. | 0:21:19 | 0:21:21 | |

And it's the phytoplankton that is the basis of all life in the ocean. | 0:21:25 | 0:21:30 | |

Every evening, the disappearance of the sun below the horizon | 0:21:35 | 0:21:41 | |

triggers the largest migration of life that takes place on our planet. | 0:21:41 | 0:21:46 | |

1,000 million tonnes of sea creatures rise from the deep ocean | 0:21:52 | 0:21:57 | |

to search for food near the surface. | 0:21:57 | 0:22:00 | |

They graze on the phytoplankton under cover of darkness. | 0:22:05 | 0:22:11 | |

Even so, they're far from safe. | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

Other marine hunters follow them, | 0:22:14 | 0:22:16 | |

some travelling up from hundreds of metres below. | 0:22:16 | 0:22:20 | |

At dawn, the whole procession returns to the safety of the dark depths. | 0:23:18 | 0:23:24 | |

The moon too has a great influence on life in the oceans. | 0:23:29 | 0:23:33 | |

It's gravitational pull creates the advances and retreats of the tide. | 0:23:35 | 0:23:41 | |

But the moon has more than a daily cycle. | 0:23:52 | 0:23:56 | |

Each month it waxes and wanes as it travels round the Earth. | 0:23:56 | 0:24:01 | |

This monthly cycle also triggers events in the ocean. | 0:24:01 | 0:24:06 | |

The Pacific coast of Costa Rica, on a very special night. | 0:24:08 | 0:24:14 | |

It's just after midnight and the tide is coming in. | 0:24:14 | 0:24:19 | |

The moon is in its last quarter, | 0:24:21 | 0:24:24 | |

exactly halfway between full and new. | 0:24:24 | 0:24:27 | |

For weeks the beach has been empty, but that is about to change. | 0:24:29 | 0:24:34 | |

At high tide, turtles start to emerge from the surf. | 0:24:34 | 0:24:39 | |

At first they come in ones and twos. | 0:24:43 | 0:24:47 | |

But within an hour, they are appearing all along the beach. | 0:24:47 | 0:24:52 | |

They are all female Ridleys turtles | 0:24:58 | 0:25:01 | |

and over the next six days or so, 400,000 will visit this one beach | 0:25:01 | 0:25:06 | |

to lay their eggs in the sand. | 0:25:06 | 0:25:10 | |

At the peak time, 5,000 are coming and going every hour. | 0:25:16 | 0:25:21 | |

The top of the beach gets so crowded that they have to clamber over one another | 0:25:21 | 0:25:27 | |

to find a bare patch where they can dig a nest hole. | 0:25:27 | 0:25:31 | |

A quarter of the world's population of Ridleys turtles come to this one beach | 0:25:33 | 0:25:39 | |

on a few key nights each year. | 0:25:39 | 0:25:42 | |

The rest of the time, they're widely distributed, searching for food, | 0:25:42 | 0:25:48 | |

most hundreds of miles from here. | 0:25:48 | 0:25:51 | |

This mass nesting is called an arribada. | 0:25:51 | 0:25:55 | |

How it's coordinated is a mystery | 0:25:55 | 0:25:58 | |

but we do know that arribadas start | 0:25:58 | 0:26:01 | |

when the moon is in its first or its last quarter. | 0:26:01 | 0:26:05 | |

40 million eggs are laid in just a few days. | 0:26:10 | 0:26:14 | |

By synchronising their nesting in this way, | 0:26:14 | 0:26:18 | |

the females ensure that six weeks later their hatchlings will emerge in such enormous numbers | 0:26:18 | 0:26:25 | |

that predators on the beach are overwhelmed and a significant number of baby turtles will survive. | 0:26:25 | 0:26:31 | |

But why do the females use a cue from the moon to help them synchronise their nesting? | 0:26:31 | 0:26:38 | |

Part of the answer to that becomes clear at dawn, | 0:26:38 | 0:26:42 | |

on the following morning. | 0:26:42 | 0:26:45 | |

The day shift of predators are arriving for their first meals. | 0:27:05 | 0:27:10 | |

Vultures have learnt that the returning tide | 0:27:14 | 0:27:18 | |

can wash freshly-laid eggs out of the sand. | 0:27:18 | 0:27:23 | |

The risk of eggs being exposed by the surf | 0:27:23 | 0:27:26 | |

may be part of the reason why turtle arribadas tend to occur | 0:27:26 | 0:27:32 | |

around the last or first quarter of the moon. | 0:27:32 | 0:27:36 | |

It's on days such as this, when the moon is neither full nor new, | 0:27:36 | 0:27:41 | |

that the tides are weakest and the sea is likely to be calmer. | 0:27:41 | 0:27:46 | |

So at these times it's easier for the female turtles | 0:27:59 | 0:28:03 | |

to make their way through the surf | 0:28:03 | 0:28:05 | |

and there's less chance of their eggs | 0:28:05 | 0:28:07 | |

being washed out of the sand and being taken by the vultures. | 0:28:07 | 0:28:10 | |

The moon's monthly cycle, and its influence on the tides, | 0:28:21 | 0:28:26 | |

triggers many events in the ocean, | 0:28:26 | 0:28:30 | |

from the spawning of the corals to the breeding cycles of fish. | 0:28:30 | 0:28:35 | |

But an even longer rhythm has the most profound effect of all - | 0:28:35 | 0:28:38 | |

the annual cycle of the sun. | 0:28:38 | 0:28:40 | |

The sun's position relative to the Earth changes through the year | 0:28:43 | 0:28:48 | |

and this produces the seasons. | 0:28:48 | 0:28:51 | |

In the north, Spring comes as the sun rises higher in the sky. | 0:28:51 | 0:28:56 | |

Off the coast of north-west America, the seas are transformed | 0:28:56 | 0:29:01 | |

by the increasing strength of the sunshine. | 0:29:01 | 0:29:05 | |

Here in Alaska, the coastal waters turn green | 0:29:07 | 0:29:12 | |

with a sudden bloom of phytoplankton. | 0:29:12 | 0:29:16 | |

Herring that have spent the winter far out to sea, | 0:29:16 | 0:29:20 | |

time their return to the shallow waters | 0:29:20 | 0:29:24 | |

to coincide with this bloom. | 0:29:24 | 0:29:26 | |

Their vast numbers start one of the oceans' most productive food chains. | 0:29:26 | 0:29:32 | |

Humpback whales are at the top of that food chain. | 0:29:45 | 0:29:50 | |

They spent the winter breeding in warmer tropical waters off Hawaii. | 0:29:50 | 0:29:55 | |

But there was little food for them there. | 0:29:55 | 0:29:59 | |

This herring bonanza provides the majority of their food for the year. | 0:29:59 | 0:30:04 | |

Stellar and Californian sea lions also return from the open ocean each year to feast off the herring. | 0:30:24 | 0:30:31 | |

The herring themselves, however, have not come here for food. | 0:30:41 | 0:30:45 | |

They are about to breed. | 0:30:45 | 0:30:48 | |

Nothing deters them as they head for even shallower waters. | 0:30:48 | 0:30:53 | |

Now the waters are so shallow that glaucous-winged gulls | 0:30:53 | 0:30:57 | |

snatch live fish from the surface. | 0:30:57 | 0:31:00 | |

In spite of these attacks and losses, the herrings swim on | 0:31:10 | 0:31:14 | |

until they reach the vegetation the females need if they are to lay. | 0:31:14 | 0:31:20 | |

Each female produces around 20,000 eggs. | 0:31:24 | 0:31:29 | |

And they're very sticky. | 0:31:29 | 0:31:32 | |

The males arrive soon after the females have spawned | 0:31:34 | 0:31:39 | |

and release their sperm in vast milky clouds. | 0:31:39 | 0:31:42 | |

Soon the excesses of the herrings' sexual spree | 0:31:46 | 0:31:50 | |

creates a thick white scum on the surface. | 0:31:50 | 0:31:54 | |

Through the season, | 0:31:54 | 0:31:56 | |

curds of sperm clog the shores for hundreds of miles, | 0:31:56 | 0:32:00 | |

from British Columbia in the south all the way to Alaska in the north. | 0:32:00 | 0:32:05 | |

After a few days, this gigantic spawning ends | 0:32:11 | 0:32:15 | |

and the herring head back out to deeper waters, | 0:32:15 | 0:32:19 | |

leaving behind them fertilised eggs plastered on every rock and strand of vegetation. | 0:32:19 | 0:32:26 | |

They time their spawning | 0:32:34 | 0:32:37 | |

so that two weeks later, when these eggs start to hatch, | 0:32:37 | 0:32:42 | |

the annual plankton bloom will have reached its height and the new-born fish fry will have plenty to eat. | 0:32:42 | 0:32:49 | |

Meanwhile, all these eggs provide food for armies of animals | 0:32:49 | 0:32:54 | |

both below and above the surface. | 0:32:54 | 0:32:57 | |

Millions of birds arrive to collect a share of the herrings' bounty. | 0:33:00 | 0:33:05 | |

Some of it is easily gathered, for millions of eggs have been washed up onto the shore. | 0:33:05 | 0:33:11 | |

This encapsulated energy is particularly valuable to migrating birds. | 0:33:11 | 0:33:17 | |

These surf birds are on the way to breeding grounds in the Arctic | 0:33:17 | 0:33:23 | |

and they had to come down to refuel. | 0:33:23 | 0:33:25 | |

Stranded herring eggs are just what they need. | 0:33:25 | 0:33:29 | |

Bonaparte's gulls collect the eggs just below the surface of the water. | 0:33:29 | 0:33:34 | |

Further out in the bay, | 0:33:36 | 0:33:38 | |

huge flocks of ducks gather. They're mostly surf scoters - | 0:33:38 | 0:33:43 | |

diving ducks that can feed off the bottom several metres down. | 0:33:43 | 0:33:48 | |

There are such huge quantities of eggs, | 0:33:50 | 0:33:54 | |

that even such a big animal as a bear finds it worthwhile to collect them. | 0:33:54 | 0:34:00 | |

The spawning of the herring is a crucial event in the lives of many animals all along the coast. | 0:34:00 | 0:34:07 | |

The whole event coincides with the plankton bloom | 0:34:07 | 0:34:11 | |

and within three weeks it's all over. | 0:34:11 | 0:34:15 | |

The migratory birds leave to continue their journey north. | 0:34:19 | 0:34:25 | |

They will not come back until the herring also return next year. | 0:34:31 | 0:34:37 | |

As the herring spawning finishes, | 0:34:40 | 0:34:42 | |

other migrants are starting to arrive, just off shore. | 0:34:42 | 0:34:47 | |

Grey whales. | 0:34:49 | 0:34:51 | |

They have followed the sun north | 0:34:56 | 0:34:59 | |

and they too are seeking the food generated by the bloom of the phytoplankton. | 0:34:59 | 0:35:05 | |

Krill are feeding off it | 0:35:05 | 0:35:08 | |

and these whales are feeding on the krill, | 0:35:08 | 0:35:11 | |

skimming it from the surface with the filter plates of baleen | 0:35:11 | 0:35:16 | |

that hang from their upper jaws. | 0:35:16 | 0:35:19 | |

Grey whales make one of the longest migrations of any marine mammal - | 0:35:19 | 0:35:24 | |

a round trip of 12,000 miles or so, | 0:35:24 | 0:35:26 | |

from their breeding grounds off Mexico, along the entire coast of North America to the Arctic Ocean. | 0:35:26 | 0:35:34 | |

They travel close to the coast, with the males and non-breeding females leading the way. | 0:35:36 | 0:35:43 | |

The last to start are the cows that have just given birth. | 0:35:43 | 0:35:46 | |

They have to wait until their new-born calves are sufficiently big and strong. | 0:35:46 | 0:35:52 | |

Their progress is necessarily slow. | 0:35:54 | 0:35:57 | |

The mothers must stay alongside their young and even a strong calf can only travel at two knots. | 0:35:57 | 0:36:04 | |

They stick even closer to the shore, | 0:36:04 | 0:36:07 | |

often within just 200 metres. | 0:36:07 | 0:36:10 | |

Killer whales. | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

They have learnt that grey whales follow traditional routes. | 0:36:16 | 0:36:20 | |

The killers have no trouble in overtaking a calf and its mother. | 0:36:20 | 0:36:26 | |

Normally, they continually call to one another | 0:36:28 | 0:36:32 | |

but now they have fallen silent. | 0:36:32 | 0:36:36 | |

The mother grey whale and her calf have no idea | 0:36:36 | 0:36:40 | |

that they've been targeted. | 0:36:40 | 0:36:44 | |

Catching up with the grey whales is the easy part for the killers. | 0:37:00 | 0:37:05 | |

They have to be cautious for they are only half the size | 0:37:05 | 0:37:10 | |

of the grey whale mother. She can inflict real damage with her tail. | 0:37:10 | 0:37:15 | |

But the killers are not after her. They're after her calf. | 0:37:23 | 0:37:27 | |

As long as the mother can keep it on the move, it will be safe. | 0:37:27 | 0:37:32 | |

She does her best to hurry it along. | 0:37:32 | 0:37:35 | |

At first, the killers avoid getting too close to the mother, but just keep pace alongside. | 0:37:35 | 0:37:42 | |

They know that the calf, going at this speed, will eventually tire. | 0:37:42 | 0:37:47 | |

After three hours of being harried in this way, | 0:37:56 | 0:38:01 | |

the calf is too exhausted to swim further. The mother has to stop. | 0:38:01 | 0:38:06 | |

This is the moment the killers have been waiting for. | 0:38:06 | 0:38:10 | |

They try to force themselves between mother and calf. | 0:38:10 | 0:38:15 | |

A calf separated from its mother will not be able to defend itself. | 0:38:33 | 0:38:38 | |

Time and again, the black fins of the killers appear | 0:38:38 | 0:38:44 | |

between the mottled backs of the grey whales. | 0:38:44 | 0:38:48 | |

At last, the killers succeed, | 0:38:53 | 0:38:56 | |

and now that they have the calf on its own, they change their tactics. | 0:38:56 | 0:39:01 | |

They leap right onto the calf and try to push it under. | 0:39:01 | 0:39:06 | |

They're trying to drown it. | 0:39:14 | 0:39:17 | |

The calf snatches a desperate breath. | 0:39:26 | 0:39:30 | |

The mother becomes increasingly agitated. | 0:39:43 | 0:39:47 | |

Frantically she tries to push her calf back to the surface so that it can breathe. | 0:39:47 | 0:39:53 | |

But now it's so exhausted that it has to be supported by its mother's body. | 0:39:55 | 0:40:02 | |

The killers won't give up. | 0:40:17 | 0:40:20 | |

Like a pack of wolves, they take turns in harassing the whales. | 0:40:20 | 0:40:25 | |

Now the whole pod is involved. | 0:40:43 | 0:40:47 | |

One of them takes a bite. | 0:40:57 | 0:41:00 | |

Soon the sea is reddened with the calf's blood | 0:41:11 | 0:41:16 | |

and the killers close in for the final act. | 0:41:16 | 0:41:19 | |

The calf is dead. | 0:41:39 | 0:41:43 | |

After a six-hour hunt, the killer whales have finally won their prize. | 0:41:46 | 0:41:51 | |

The mother, bereft, has to continue her migration north on her own. | 0:41:57 | 0:42:03 | |

She leaves behind the carcass of a calf that she cherished | 0:42:07 | 0:42:11 | |

for 13 months in her womb, for which she delayed her own journey to find food. | 0:42:11 | 0:42:17 | |

The pod of 15 killer whales spent over six hours trying to kill this calf, but now, having succeeded, | 0:42:20 | 0:42:27 | |

they've eaten nothing more than its lower jaw and its tongue. | 0:42:27 | 0:42:33 | |

Valuable food like this will not go to waste in the ocean. | 0:42:38 | 0:42:43 | |

Before long, the carcass will sink to the very bottom of this deep sea. | 0:42:43 | 0:42:49 | |

But even there, its flesh will not be wasted. | 0:42:49 | 0:42:52 | |

Over a mile down, in the total darkness of the deep ocean, | 0:42:55 | 0:42:59 | |

the body of another grey whale, a 30-tonne adult. | 0:42:59 | 0:43:04 | |

It settled here only a few weeks ago. | 0:43:04 | 0:43:07 | |

Already it has attracted hundreds of hackfish. | 0:43:07 | 0:43:12 | |

These scavengers, over half a metre long and as thick as your arm, | 0:43:17 | 0:43:22 | |

are only found in the deep sea. | 0:43:22 | 0:43:25 | |

They have been attracted by the faint whiff of decay suffusing through the water for miles around. | 0:43:25 | 0:43:31 | |

With their heads buried in the whale's flesh, | 0:43:34 | 0:43:38 | |

they breathe through gill openings on their sides. | 0:43:38 | 0:43:42 | |

They're very primitive creatures, | 0:43:42 | 0:43:44 | |

not even true fish for they lack jaws. | 0:43:44 | 0:43:48 | |

They feed not by biting, | 0:43:48 | 0:43:50 | |

but by rasping off flesh with two rows of horny teeth. | 0:43:50 | 0:43:55 | |

In just a few hours, a hackfish can eat | 0:43:55 | 0:43:59 | |

several times its own weight of rotting flesh. | 0:43:59 | 0:44:04 | |

Next to arrive, a sleeper shark. | 0:44:04 | 0:44:08 | |

It moves so slowly to conserve energy - | 0:44:13 | 0:44:18 | |

an important strategy for so large an animal surviving in such a poor habitat. | 0:44:18 | 0:44:24 | |

Sleeper sharks live over a mile down | 0:44:29 | 0:44:33 | |

and grow to over seven metres long. | 0:44:33 | 0:44:36 | |

They can go for months without food, cruising along the bottom, waiting for rare bonanzas, | 0:44:37 | 0:44:44 | |

such as this one, to arrive from above. | 0:44:44 | 0:44:48 | |

A whole range of different deep-sea scavengers | 0:44:53 | 0:44:59 | |

will feast on this carcass for a long time, before all its nutriment has been consumed. | 0:44:59 | 0:45:06 | |

18 months later, all that is left is a perfect skeleton stripped bare. | 0:45:06 | 0:45:11 | |

The sun's energy that was captured and turned into living tissue by the phytoplankton | 0:45:11 | 0:45:17 | |

has been transferred from one link to another in the food chain | 0:45:17 | 0:45:22 | |

and ended up as far away from the sun as possible on this planet, | 0:45:22 | 0:45:27 | |

at the bottom of the deep sea. | 0:45:27 | 0:45:30 | |

But some energy also returns from the deep. | 0:45:30 | 0:45:35 | |

Millions of opalescent squid | 0:45:39 | 0:45:42 | |

are on their way to the shallows. They've come up here to mate. | 0:45:42 | 0:45:47 | |

As the males grab the females, their tentacles flush red. | 0:45:47 | 0:45:52 | |

For most of the year, these squid live at a depth of about 500 metres. | 0:45:53 | 0:45:59 | |

They only come together for a few weeks. | 0:45:59 | 0:46:03 | |

Just one school was estimated to contain animals that weigh around 4,000 tonnes. | 0:46:03 | 0:46:10 | |

Wave after wave rise from the depths, | 0:46:19 | 0:46:23 | |

and soon the sea-bed and shallows are strewn with dense patches of egg capsules several metres across. | 0:46:23 | 0:46:30 | |

As each female adds another capsule to the pile, | 0:46:34 | 0:46:39 | |

the males fight to fertilise its contents. | 0:46:39 | 0:46:43 | |

The squid make their huge journey into the shallows | 0:46:56 | 0:47:01 | |

because their eggs will develop faster in the warmer water here. | 0:47:01 | 0:47:06 | |

When the young emerge, they will find food more easily than they would in the ocean depths. | 0:47:06 | 0:47:13 | |

Dawn the next morning, | 0:47:14 | 0:47:17 | |

and the sea-bed for miles around is covered in egg capsules. | 0:47:17 | 0:47:21 | |

The squid themselves have all gone. | 0:47:21 | 0:47:24 | |

Many will have died but some have returned to their home in the deep. | 0:47:24 | 0:47:29 | |

They will not return to the light of the sun | 0:47:29 | 0:47:33 | |

until the next time they are driven up by the urge to spawn. | 0:47:33 | 0:47:38 | |

The enormous size of the oceans, | 0:47:48 | 0:47:51 | |

and the fact that we know so little about many of the creatures there, | 0:47:51 | 0:47:54 | |

have presented the film makers behind the Blue Planet series with difficult challenges. | 0:47:54 | 0:48:00 | |

None more so than the mighty blue whale. | 0:48:00 | 0:48:02 | |

Despite their massive size, blue whales have hardly ever been filmed. | 0:48:02 | 0:48:07 | |

And there are good reasons for that. They're among the fastest marine creatures. Faster than many boats. | 0:48:07 | 0:48:15 | |

Except for a few minutes to breathe, they stay submerged. | 0:48:15 | 0:48:19 | |

Even when they surface, they're timid and difficult to approach. | 0:48:19 | 0:48:24 | |

So, to capture blue whales on film is very difficult, | 0:48:24 | 0:48:28 | |

and it took the team many months and some ingenuity, | 0:48:28 | 0:48:32 | |

just to get these few rare images. | 0:48:32 | 0:48:35 | |

Just finding and keeping up with blue whales is a real challenge. | 0:48:41 | 0:48:47 | |

One of the largest blue whale populations migrates back and forth, | 0:48:48 | 0:48:52 | |

along the coast of California and Mexico each year. | 0:48:52 | 0:48:56 | |

For three seasons our camera teams were on standby, | 0:48:56 | 0:49:00 | |

waiting for passing whales. | 0:49:00 | 0:49:02 | |

In theory, a microlite is perfect for filming. It's inexpensive, | 0:49:06 | 0:49:11 | |

it doesn't disturb the whales and it's possible to land and dive in the water. | 0:49:11 | 0:49:17 | |

But as the migration continued south, | 0:49:18 | 0:49:21 | |

the whales were soon out of range and another strategy was called for. | 0:49:21 | 0:49:27 | |

We followed the whales south to Mexico and the Gulf of California. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:32 | |

On several consecutive years recently, blue whales have been regularly sighted here, | 0:49:32 | 0:49:39 | |

and the Gulf's calm waters seemed an ideal location for filming. | 0:49:39 | 0:49:44 | |

However, getting close enough to get film images wasn't going to be easy, | 0:49:44 | 0:49:48 | |

as experienced cameraman, Rick Rosenthal explains. | 0:49:48 | 0:49:53 | |

Filming whales around the world, I think that they are like either | 0:49:53 | 0:49:58 | |

a large aeroplane or... Very streamlined and it's difficult | 0:49:58 | 0:50:02 | |

to get an image. You're going to have to be very patient, if you're gonna get any behaviour whatsoever. | 0:50:02 | 0:50:09 | |

'Mary Lee, Mary Lee, Santa Emily, come back?' | 0:50:09 | 0:50:13 | |

The first problem was to find the whale | 0:50:13 | 0:50:16 | |

in 30,000 square miles of water. | 0:50:16 | 0:50:19 | |

OK, yes, you're just turning around the moon for us, | 0:50:19 | 0:50:22 | |

that's beautiful. | 0:50:22 | 0:50:23 | |

Using the locations of previous sightings, the team enlisted | 0:50:23 | 0:50:28 | |

the help of experienced pilot Sandy Lanham, who had a trained eye for spotting blue whales from the air. | 0:50:28 | 0:50:35 | |

I've been working with scientists for whale research for 10 years. | 0:50:35 | 0:50:40 | |

We're convinced that the only way to cover a body of water this large, is to use an aeroplane. | 0:50:40 | 0:50:47 | |

Without directions from the air, | 0:50:50 | 0:50:52 | |

the team would have found it far harder to catch up with the whales. | 0:50:52 | 0:50:57 | |

Once the boat had gained visual contact with the blue whale, | 0:51:01 | 0:51:06 | |

they aimed to get a good shot as it came up for air. | 0:51:06 | 0:51:10 | |

It was essential not to cause any disturbance. | 0:51:10 | 0:51:14 | |

The trick was to try and sneak ahead of the whale, predicting where it would surface next. | 0:51:14 | 0:51:21 | |

You need special permission and a good deal of experience to get this close to whales. | 0:51:24 | 0:51:31 | |

I dove down | 0:51:33 | 0:51:34 | |

and could see a white glowing body and turned the camera on | 0:51:34 | 0:51:39 | |

and the result was, you know, | 0:51:39 | 0:51:42 | |

a nice image of a huge blue whale | 0:51:42 | 0:51:46 | |

gliding by me like a giant torpedo. | 0:51:46 | 0:51:49 | |

Getting close to blue whales in a small boat | 0:51:49 | 0:51:53 | |

without causing disturbance | 0:51:53 | 0:51:55 | |

requires a good understanding of their behaviour. | 0:51:55 | 0:51:57 | |

You NEVER chase whales. | 0:51:57 | 0:52:00 | |

When they come up for air, their tails leave a smooth patch of water called a footprint. | 0:52:02 | 0:52:08 | |

These indicate its speed and direction. | 0:52:08 | 0:52:11 | |

If you're lucky, you can gauge where it will surface in about 15 minutes. | 0:52:11 | 0:52:16 | |

After countless attempts at this guessing game, | 0:52:18 | 0:52:22 | |

Rick was finally in the right place at the right time. | 0:52:22 | 0:52:26 | |

The whale was surfacing near the boat. At one time it came up close, | 0:52:26 | 0:52:31 | |

we were able to manoeuvre the boat quietly so we were on top of it, | 0:52:31 | 0:52:37 | |

looking down at it - enormous tail and the entire body stretched out, | 0:52:37 | 0:52:43 | |

maybe 50-60 feet long. | 0:52:43 | 0:52:45 | |

It's one of those Captain Ahab, Moby Dick tales | 0:52:50 | 0:52:54 | |

when you are looking down at the entire whale | 0:52:54 | 0:52:57 | |

and it was very quiet and not concerned about us. | 0:52:57 | 0:53:01 | |

It took some breaths and submerged and came up again | 0:53:01 | 0:53:04 | |

and we manoeuvred again and got in the same position. | 0:53:04 | 0:53:07 | |

We were looking down at the entire whale underneath us. | 0:53:07 | 0:53:11 | |

That's an extraordinary feeling for anybody. | 0:53:11 | 0:53:13 | |

Subtitles by Gabby De Gregorio and Nick Holmes - 2001 | 0:53:52 | 0:53:55 | |

E-mail [email protected]. | 0:53:55 | 0:53:58 |