Berlin to the Rhein Great Continental Railway Journeys

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Berlin to the Rhein. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

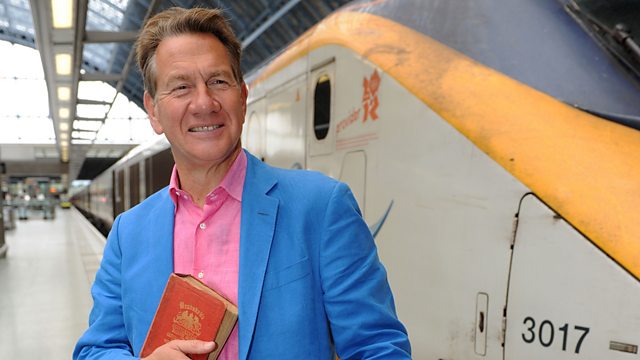

I'm embarking on a new railway adventure | 0:00:04 | 0:00:07 | |

that will take me across the heart of Europe. | 0:00:07 | 0:00:10 | |

I'll be using this, my Bradshaw's Continental Railway Guide, | 0:00:10 | 0:00:15 | |

dated 1913, which opened up an exotic world of foreign travel | 0:00:15 | 0:00:20 | |

for the British tourist. | 0:00:20 | 0:00:21 | |

It told travellers where to go, what to see and how to navigate | 0:00:23 | 0:00:28 | |

the thousands of miles of tracks criss-crossing the continent. | 0:00:28 | 0:00:31 | |

Now, a century later, | 0:00:31 | 0:00:34 | |

I'm using my copy to reveal an era of great optimism and energy, | 0:00:34 | 0:00:38 | |

where technology, industry, science and the arts were flourishing. | 0:00:38 | 0:00:42 | |

I want to rediscover that lost Europe that in 1913 couldn't know | 0:00:42 | 0:00:48 | |

that its way of life would shortly be swept aside by the advent of war. | 0:00:48 | 0:00:52 | |

Steered by my 1913 railway guide, | 0:01:09 | 0:01:12 | |

I'm journeying across prosperous pre-war Europe. | 0:01:12 | 0:01:16 | |

This leg takes me to Imperial Germany, whose emperor, | 0:01:18 | 0:01:22 | |

Queen Victoria's grandson Kaiser Wilhelm II, | 0:01:22 | 0:01:25 | |

would soon take family feuding to a tragic new level. | 0:01:25 | 0:01:29 | |

So the two countries that went to war | 0:01:29 | 0:01:32 | |

-were ruled over by first cousins? -Yes. | 0:01:32 | 0:01:34 | |

I'll take to the skies on a train... | 0:01:34 | 0:01:37 | |

I can see into everybody's window, I can see into everybody's house. | 0:01:37 | 0:01:41 | |

..sample local cuisine... | 0:01:41 | 0:01:43 | |

When on the Rhine, eat as Rhinelanders do. | 0:01:43 | 0:01:47 | |

'..appreciate local smells...' That IS very, very strong. | 0:01:47 | 0:01:50 | |

..meet local characters... | 0:01:50 | 0:01:52 | |

-Hello, my beauty! -Nice to meet you! | 0:01:52 | 0:01:54 | |

'..and enjoy the fruits of its ancient vineyards.' | 0:01:54 | 0:01:57 | |

I like it very much. | 0:01:57 | 0:01:59 | |

My journey begins in the capital, Berlin, | 0:02:06 | 0:02:09 | |

heads west to the city of Magdeburg and the picturesque Harz Mountains. | 0:02:09 | 0:02:15 | |

I'll then discover the majesty of Hanover, from where I'll continue | 0:02:15 | 0:02:18 | |

to Germany's industrial Ruhr Valley at Essen, | 0:02:18 | 0:02:23 | |

followed then by the Gothic beauty of Cologne. | 0:02:23 | 0:02:26 | |

I'll head towards Koblenz, | 0:02:26 | 0:02:27 | |

learning what role the railways played in the First World War, | 0:02:27 | 0:02:31 | |

before joining the tourist trail | 0:02:31 | 0:02:33 | |

down the castle-studded banks of the River Rhine. | 0:02:33 | 0:02:36 | |

In 1913, the so-called German Empire was then a young country, | 0:02:39 | 0:02:45 | |

having been brought together just a few decades before | 0:02:45 | 0:02:48 | |

out of a group of formerly independent states. | 0:02:48 | 0:02:51 | |

My Bradshaw's tells me that the German Empire consists of 25 states | 0:02:51 | 0:02:56 | |

and the Imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine, | 0:02:56 | 0:02:59 | |

and it then lists them in order of magnitude - | 0:02:59 | 0:03:02 | |

beginning, of course, with Prussia - | 0:03:02 | 0:03:04 | |

and I'm headed now for its glittering capital, Berlin. | 0:03:04 | 0:03:08 | |

I'm arriving at Berlin's Hauptbahnhof, | 0:03:29 | 0:03:31 | |

a spectacular product of the new, unified Germany. | 0:03:31 | 0:03:36 | |

This five-tiered glass and steel structure | 0:03:36 | 0:03:40 | |

opened in 2006 at a cost of £480 million | 0:03:40 | 0:03:43 | |

to provide travellers with a one-stop connection north to south | 0:03:43 | 0:03:49 | |

and, more symbolically, East to West. | 0:03:49 | 0:03:52 | |

I love Berlin's new main railway station, | 0:03:57 | 0:04:00 | |

its two crystal tunnels intersecting at this point. | 0:04:00 | 0:04:04 | |

It's an aesthetic and technological triumph, | 0:04:04 | 0:04:07 | |

and yet, despite being entirely modern, | 0:04:07 | 0:04:09 | |

it's reminiscent of Victorian railway stations | 0:04:09 | 0:04:13 | |

made of cast iron and glass. | 0:04:13 | 0:04:15 | |

In 1913, Germany's engineering and industrial prowess | 0:04:19 | 0:04:21 | |

was being nurtured by its vehemently nationalist emperor. | 0:04:21 | 0:04:25 | |

Kaiser Wilhelm was obsessed with bettering the two major powers | 0:04:25 | 0:04:29 | |

of the previous century. | 0:04:29 | 0:04:31 | |

He aimed for a navy to emulate Britain's, | 0:04:31 | 0:04:34 | |

and Berlin, his capital, was fast rivalling Paris. | 0:04:34 | 0:04:38 | |

"Berlin," asserts my Bradshaw's, | 0:04:40 | 0:04:43 | |

"is THE most modern of the great cities of Europe. | 0:04:43 | 0:04:46 | |

"Broad streets, handsome buildings, spacious squares and open places | 0:04:46 | 0:04:52 | |

"rendered more attractive by trees and statues." | 0:04:52 | 0:04:56 | |

And at a time when Britain was suffering from industrial strife, | 0:04:56 | 0:05:00 | |

turmoil in Ireland and suffragette outrages, it adds, perhaps | 0:05:00 | 0:05:04 | |

a little enviously, "Cleanliness and order are everywhere." | 0:05:04 | 0:05:08 | |

I'm heading to the heart of Wilhelm's Imperial Berlin | 0:05:11 | 0:05:14 | |

and probably the city's best-known landmark. | 0:05:14 | 0:05:17 | |

In 1913, the Brandenburg Gate would have beckoned visitors towards | 0:05:17 | 0:05:21 | |

the Kaiser's Palace. | 0:05:21 | 0:05:23 | |

But after the Second World War, it symbolically barred passage | 0:05:23 | 0:05:27 | |

between communist East and capitalist West Germany. | 0:05:27 | 0:05:30 | |

'Matt Robinson is my guide.' | 0:05:30 | 0:05:33 | |

Why is the Brandenburg Gate such an important symbol for Germany? | 0:05:33 | 0:05:38 | |

It was the gate used by the king, who had come from the royal district | 0:05:38 | 0:05:41 | |

further down Unter Den Linden passing through to the Tiergarten, | 0:05:41 | 0:05:44 | |

and this is where Germans came to celebrate in 1871 | 0:05:44 | 0:05:47 | |

when Germany became Germany. It's where the German soldiers | 0:05:47 | 0:05:51 | |

marched back through in December 1918 | 0:05:51 | 0:05:54 | |

following the armistice in November, the end of the First World War. | 0:05:54 | 0:05:58 | |

What happened to the Brandenburg Gate during the Cold War? | 0:05:58 | 0:06:01 | |

Between 1961 and 1989, the Brandenburg Gate | 0:06:01 | 0:06:05 | |

was in the death strip of the Berlin Wall. | 0:06:05 | 0:06:08 | |

This is the area in between the two walls that existed. | 0:06:08 | 0:06:11 | |

This is the area where East German border guards | 0:06:11 | 0:06:13 | |

were shooting people as traitors to the state | 0:06:13 | 0:06:16 | |

as they tried to escape to the West. | 0:06:16 | 0:06:18 | |

The East Germans never referred to the Berlin Wall | 0:06:18 | 0:06:21 | |

as the Berlin Wall that they built to stop East Germans from leaving. | 0:06:21 | 0:06:24 | |

It was always the "anti-fascist protection barrier" | 0:06:24 | 0:06:26 | |

to stop the fascists in the West from getting to the East | 0:06:26 | 0:06:30 | |

and corrupting this East German socialist paradise. | 0:06:30 | 0:06:33 | |

It's quite a thought, isn't it? | 0:06:33 | 0:06:36 | |

A bit small, this one. | 0:06:36 | 0:06:39 | |

'For all its melancholy history, the Gate is now a tourist attraction. | 0:06:39 | 0:06:43 | |

'But I'm juggling a busy schedule and need to move on.' | 0:06:44 | 0:06:47 | |

My Bradshaw's says of the railway lines | 0:06:50 | 0:06:52 | |

that they're "probably more useful for residents than for tourists, | 0:06:52 | 0:06:56 | |

"whose convenience is better served by the trams." Can we take a tram? | 0:06:56 | 0:07:00 | |

We can. There are none around here | 0:07:00 | 0:07:02 | |

-but we can certainly head further into the east. -Very good. | 0:07:02 | 0:07:06 | |

In the decades before my 1913 guidebook was published, | 0:07:09 | 0:07:13 | |

the great European powers were in a race | 0:07:13 | 0:07:15 | |

for technological supremacy. | 0:07:15 | 0:07:18 | |

And when the world's first electric tram ran in Berlin in 1881, | 0:07:18 | 0:07:22 | |

the city took a step ahead of its rivals. | 0:07:22 | 0:07:25 | |

So, historically, the trams have been pretty important in Berlin? | 0:07:25 | 0:07:29 | |

As Berlin developed in the late 1800s as the Imperial capital | 0:07:29 | 0:07:33 | |

of Germany, there was a necessity to get workers to the factories | 0:07:33 | 0:07:37 | |

in the central parts of the city. | 0:07:37 | 0:07:39 | |

Thus, the public transportation network developed | 0:07:39 | 0:07:42 | |

to become one of the largest in the country. | 0:07:42 | 0:07:44 | |

In fact, to this day it's still the largest in Germany. | 0:07:44 | 0:07:47 | |

How big did this network become? | 0:07:47 | 0:07:49 | |

By the late 1920s, it was massive. | 0:07:49 | 0:07:53 | |

There was some 600 kilometres of track throughout the city, | 0:07:53 | 0:07:56 | |

90 different lines, in fact, in Berlin alone. | 0:07:56 | 0:07:59 | |

1913 Germany was both wealthy and learned. | 0:08:01 | 0:08:06 | |

To speed industrial and military development, | 0:08:06 | 0:08:08 | |

Wilhelm's government gave unprecedented financial support | 0:08:08 | 0:08:12 | |

to universities and research institutes. | 0:08:12 | 0:08:15 | |

In another success for the Kaiser, | 0:08:17 | 0:08:19 | |

the world's centre of science and technology shifted | 0:08:19 | 0:08:22 | |

from Britain and France to Berlin. | 0:08:22 | 0:08:24 | |

I've come to the Archenhold Observatory in search of a genius | 0:08:28 | 0:08:31 | |

who was developing theories at the time my guidebook was written | 0:08:31 | 0:08:34 | |

that were to change science for ever. | 0:08:34 | 0:08:38 | |

Dr Felix Luhning is head of astronomy at Archenhold, | 0:08:38 | 0:08:43 | |

-'in the southeast of the city.' Hello, Felix. -Hello, Michael. | 0:08:43 | 0:08:47 | |

My guidebook tells me that Berlin's scientific institutions | 0:08:47 | 0:08:50 | |

are of worldwide renown. | 0:08:50 | 0:08:51 | |

Was it important to the Kaiser, the German Reich, to promote science? | 0:08:51 | 0:08:56 | |

Yes. It was a matter of reputation | 0:08:56 | 0:09:00 | |

and it was also a matter of, um, | 0:09:00 | 0:09:04 | |

well, so to speak, support for big business. | 0:09:04 | 0:09:07 | |

In 1879, the centrepiece of Berlin's Trade Fair | 0:09:09 | 0:09:13 | |

was the world's first electric railway. | 0:09:13 | 0:09:15 | |

Then, the city amazed visitors again by unveiling | 0:09:15 | 0:09:20 | |

a huge and powerful telescope - the Treptow. | 0:09:20 | 0:09:24 | |

Well, it's absolutely the biggest telescope that I'VE ever seen. | 0:09:26 | 0:09:29 | |

When was it built and how big is it? | 0:09:29 | 0:09:31 | |

Well, it was built in 1896 | 0:09:31 | 0:09:35 | |

and it is the longest telescope of the world, 21 metres' focus. | 0:09:35 | 0:09:38 | |

Such a telescope at the end of the 19th century must have | 0:09:38 | 0:09:41 | |

-attracted visitors from far and wide. -Yes, that's right. | 0:09:41 | 0:09:43 | |

The observatory was crowded with people. | 0:09:43 | 0:09:46 | |

Everybody was curious about what to see in this big telescope. | 0:09:46 | 0:09:49 | |

Can we see it operating? | 0:09:49 | 0:09:51 | |

Yes, of course. Very simple, just push the button. | 0:09:51 | 0:09:54 | |

'With a magnification factor of 210, the telescope provides | 0:09:55 | 0:10:00 | |

'detailed observations of the moon and planets. | 0:10:00 | 0:10:03 | |

'But just after my 1913 guidebook was written, an event | 0:10:03 | 0:10:06 | |

'at the Archenhold Observatory had an even bigger impact on science.' | 0:10:06 | 0:10:10 | |

In 1915, the most influential scientist of the century, | 0:10:10 | 0:10:14 | |

Albert Einstein, | 0:10:14 | 0:10:16 | |

'stunned the world with his first-ever speech on relativity.' | 0:10:16 | 0:10:20 | |

-So this is where Albert Einstein gave his lecture? -Yes. | 0:10:22 | 0:10:25 | |

Imagine this hall filled with visitors and reporters | 0:10:25 | 0:10:29 | |

writing down articles. | 0:10:29 | 0:10:30 | |

Born in Germany in 1879, | 0:10:30 | 0:10:33 | |

Einstein developed his general theory of relativity | 0:10:33 | 0:10:36 | |

to explain the Newtonian mystery of gravity. | 0:10:36 | 0:10:39 | |

-And what did it change? -It changed everything. | 0:10:39 | 0:10:41 | |

It changed the science, it changed astronomy, | 0:10:41 | 0:10:46 | |

it changed also nuclear physics and it changed cosmology. | 0:10:46 | 0:10:51 | |

Einstein's approach to science was radical, | 0:10:51 | 0:10:54 | |

and his Nobel Prize in 1921 made him a genius celebrity. | 0:10:54 | 0:10:58 | |

But he could explain his complex ideas in amusing layman's terms. | 0:10:58 | 0:11:03 | |

Einstein apparently joked that the theory of relativity meant | 0:11:03 | 0:11:07 | |

two hours spent with a beautiful girl passed in a minute, | 0:11:07 | 0:11:09 | |

and a minute spent on a hot stove seemed like two hours. | 0:11:09 | 0:11:12 | |

But presumably what he was really saying was | 0:11:12 | 0:11:14 | |

that time itself is elastic, that it is relative. | 0:11:14 | 0:11:17 | |

Yes. He showed that it depended on how you are moving. | 0:11:17 | 0:11:21 | |

The faster you're moving, the slower time goes by for you. | 0:11:21 | 0:11:26 | |

An avowed pacifist, Einstein devised the world-famous equation "E=mc2", | 0:11:26 | 0:11:33 | |

which confirmed the relationship between mass and energy - | 0:11:33 | 0:11:36 | |

an insight necessary to develop the atomic bomb. | 0:11:36 | 0:11:40 | |

A consequence that made him uncomfortable in later life. | 0:11:40 | 0:11:43 | |

I believe that railways played an important part in his theory. | 0:11:43 | 0:11:46 | |

Yes, because railways are a perfect example for the relativity | 0:11:46 | 0:11:51 | |

of movements. They are a perfect example for a constant moving system. | 0:11:51 | 0:11:57 | |

Using models, Einstein explained how a train | 0:11:57 | 0:12:00 | |

travelling along the horizon will seem to move at a much slower speed | 0:12:00 | 0:12:03 | |

than one rushing past you on a platform. | 0:12:03 | 0:12:05 | |

But they are, in fact, going at the same speed. | 0:12:05 | 0:12:09 | |

Einstein showed that things can't be regarded separately. | 0:12:09 | 0:12:14 | |

Time, mass and space are connected together. | 0:12:14 | 0:12:19 | |

Felix, I don't think I'll ever think the same way | 0:12:19 | 0:12:21 | |

about a railway journey again. Thank you. | 0:12:21 | 0:12:23 | |

To leave Berlin, I'm heading for Charlottenburg in the west of the city. | 0:12:25 | 0:12:29 | |

The affluent suburb is still home to an ornate palace and gardens | 0:12:29 | 0:12:34 | |

which my 1913 guidebook notes | 0:12:34 | 0:12:36 | |

"contains the mausoleum of the Kaiser's late mother and father." | 0:12:36 | 0:12:39 | |

But I'm destined for more rural landscapes | 0:12:41 | 0:12:45 | |

-..Heute? -Heute, ja. | 0:12:45 | 0:12:48 | |

-26.60. -Danke. | 0:12:48 | 0:12:51 | |

Danke, auf Wiedersehen. | 0:12:55 | 0:12:56 | |

I'm travelling via Magdeburg to the natural beauties of Saxony-Anhalt, | 0:13:00 | 0:13:04 | |

a state steeped in legend. | 0:13:04 | 0:13:06 | |

My Bradshaw's Guide tells me that German scenery | 0:13:10 | 0:13:13 | |

"is generally pleasing and varied, | 0:13:13 | 0:13:15 | |

"and there are many pretty mountain chains of moderate elevation." | 0:13:15 | 0:13:20 | |

I'm headed for the Harz Mountains, which Edwardian travellers enjoyed | 0:13:20 | 0:13:24 | |

for the beautiful fresh air and the stunning views. | 0:13:24 | 0:13:28 | |

The Harz Mountains extend for 100 kilometres. | 0:13:38 | 0:13:40 | |

Maximising its engineering resources, | 0:13:42 | 0:13:44 | |

Germany laid three railways here in the late 19th century, | 0:13:44 | 0:13:47 | |

primarily to transport the range's rich minerals. | 0:13:47 | 0:13:51 | |

When the third scaled the mountain's tallest peak, the Brocken, | 0:13:53 | 0:13:55 | |

it became the country's longest and most scenic narrow-gauge railway. | 0:13:55 | 0:14:00 | |

And I'm excited to ride it because it runs on steam. | 0:14:02 | 0:14:06 | |

My Bradshaw's tells me that the Brocken is "3,145 feet high, | 0:14:15 | 0:14:21 | |

"the highest summit of the Harz Mountains." | 0:14:21 | 0:14:23 | |

What better way to get there than on this delightful steam railway? | 0:14:23 | 0:14:27 | |

This must be one of the great train rides in Europe. | 0:14:45 | 0:14:49 | |

The steam engine curling ahead, the train weaving between the trees | 0:14:49 | 0:14:54 | |

as we make our way, panting, towards the summit of the Brocken. | 0:14:54 | 0:14:59 | |

Was ist das? | 0:15:10 | 0:15:12 | |

-Waldbeer. -Mm-hm. | 0:15:12 | 0:15:15 | |

-Schlehe mit Rum. -Ah-ha, Schlehe mit Rum. -Ja. | 0:15:15 | 0:15:19 | |

Mm-hmm. Something with rum. | 0:15:19 | 0:15:21 | |

Ja, das geht. | 0:15:21 | 0:15:24 | |

-Very attractive with their pictures of the locomotives. -Three euro. | 0:15:24 | 0:15:28 | |

Danke, danke. | 0:15:28 | 0:15:29 | |

Sehr gut! Good for the Herz? | 0:15:29 | 0:15:31 | |

-Ja. -Good for the heart? -Ja, sehr gut. | 0:15:31 | 0:15:35 | |

I believe it. Thank you. Mm. | 0:15:35 | 0:15:37 | |

Good for the heart in the Harz Mountain. Get it? | 0:15:39 | 0:15:42 | |

The Harz Mountains are famous in German folklore. | 0:15:42 | 0:15:46 | |

Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty and Little Red Riding Hood | 0:15:46 | 0:15:50 | |

are all stories thought to have emanated from here. | 0:15:50 | 0:15:52 | |

But the Brocken is most famous for a pivotal scene in German literature. | 0:15:52 | 0:15:58 | |

Set on a night of spooks similar to Halloween - called Walpurgis - | 0:15:58 | 0:16:03 | |

in Faust, an 18th-century play by Goethe, | 0:16:03 | 0:16:06 | |

witches worship the devil on this peak, | 0:16:06 | 0:16:09 | |

and evidently, even now, the odd one may be attracted here. | 0:16:09 | 0:16:14 | |

-Hello, my beauty. -Hello, nice to meet you! -My beauty, indeed! | 0:16:15 | 0:16:20 | |

-On the mountain! -Why are you dressed as a witch? Warum Hexe? | 0:16:20 | 0:16:24 | |

-Hier ist der Brocken, der Brocken... -This is the Brocken mountain. | 0:16:24 | 0:16:27 | |

..auf dem Gipfel | 0:16:27 | 0:16:29 | |

um dem Teufel auf den Arsch zu kussen und holen sich ihre Hexenkraft. | 0:16:29 | 0:16:34 | |

SHE LAUGHS Da sind wir immer dabei! | 0:16:34 | 0:16:37 | |

I don't understand everything, but I think she's telling me | 0:16:37 | 0:16:40 | |

that for ten years she's been coming here, and on the Brocken Mountain, | 0:16:40 | 0:16:43 | |

the witches practise witchcraft on Walpurgis Night. | 0:16:43 | 0:16:46 | |

-Walpurgis Night, yes. -Is that right? -Yes! | 0:16:46 | 0:16:49 | |

Oh! Do Hexe like a drink? | 0:16:49 | 0:16:53 | |

Yes. Oh, yes! | 0:16:53 | 0:16:54 | |

MICHAEL LAUGHS Woo! | 0:16:54 | 0:16:56 | |

Oh! | 0:16:56 | 0:16:58 | |

-Mm, that's the way to do it, isn't it? -Wow, super! It's for you! -Ja. | 0:17:02 | 0:17:05 | |

-Did you leave any?! Cheers! -Cheers! -Mmm! | 0:17:05 | 0:17:10 | |

Sehr gut. | 0:17:12 | 0:17:14 | |

Auf Wiedersehen! | 0:17:15 | 0:17:16 | |

..Sehr gut, ja! | 0:17:18 | 0:17:20 | |

In 1913, lured by the Brocken's scenery and witches, | 0:17:20 | 0:17:26 | |

at least 50,000 tourists trekked to the summit. | 0:17:26 | 0:17:30 | |

Then, as now, it was traditional to make the 1,142-metre ascent on foot. | 0:17:30 | 0:17:37 | |

-We walked from... -Torfhaus. | 0:17:37 | 0:17:39 | |

-Torfhaus. -Ah-ha! -It's seven kilometres. | 0:17:39 | 0:17:43 | |

-And how long has that taken you? -12 o'clock. -12 o'clock you set out. | 0:17:43 | 0:17:47 | |

-2.30 now, so two hours and twenty minutes. -Ja. -Very good. Healthy! -Ja. | 0:17:47 | 0:17:53 | |

-Hello, sir. -Hello, sir. | 0:17:53 | 0:17:55 | |

-Have you walked a long way? Oh, not a long way. -From Schriker. | 0:17:55 | 0:17:59 | |

-And how long has that taken you? -Oh, six kilometres, about two hours. | 0:17:59 | 0:18:03 | |

-Do you come up the Brocken very often? -No, it's the first time. | 0:18:03 | 0:18:06 | |

-Really? -Yes. -Congratulations! -Thank you. | 0:18:06 | 0:18:09 | |

Leaving the natural beauty of the Harz Mountains behind, | 0:18:14 | 0:18:19 | |

I'm bound for my next destination - Hanover. | 0:18:19 | 0:18:22 | |

The city may help me to understand why Kaiser Wilhelm was so driven | 0:18:22 | 0:18:27 | |

by a sense of rivalry with Britain to the West and Russia to the East. | 0:18:27 | 0:18:31 | |

Bradshaw's tells me that "mid-Europe time, | 0:18:35 | 0:18:38 | |

"one hour in advance of Greenwich Time, | 0:18:38 | 0:18:41 | |

"is observed on all lines in Germany. | 0:18:41 | 0:18:43 | |

"The fares are less than in most other parts of the continent, | 0:18:43 | 0:18:46 | |

"averaging one and two-fifths pence per mile, first class," | 0:18:46 | 0:18:52 | |

which shows the limitations of using a guidebook 100 years old. | 0:18:52 | 0:18:56 | |

"Railway carriages in Germany are clean and comfortable," | 0:18:56 | 0:18:59 | |

so some things haven't changed at all. | 0:18:59 | 0:19:02 | |

With its beautiful buildings and highly admired culture, | 0:19:13 | 0:19:17 | |

Hanover, a formerly independent German kingdom which had become | 0:19:17 | 0:19:21 | |

a province of Prussia, was a magnet | 0:19:21 | 0:19:23 | |

for early 20th-century British travellers | 0:19:23 | 0:19:25 | |

with an interest in royalty. | 0:19:25 | 0:19:27 | |

On my British railway journeys, | 0:19:30 | 0:19:32 | |

I have often followed in the footsteps of Queen Victoria. | 0:19:32 | 0:19:35 | |

In Hanover, my Bradshaw's draws my attention to Schloss Herrenhausen, | 0:19:35 | 0:19:40 | |

where George I and George II lived. So, extraordinarily, | 0:19:40 | 0:19:45 | |

here in the heart of Germany, I find myself close to the origins | 0:19:45 | 0:19:48 | |

of Queen Victoria, who was our last monarch in the line of Hanover. | 0:19:48 | 0:19:53 | |

I've made my way to the impressive Royal Palace | 0:19:59 | 0:20:02 | |

and botanical gardens of Herrenhausen to find out more | 0:20:02 | 0:20:05 | |

from Petra Kiel-Heurich, a local guide. | 0:20:05 | 0:20:07 | |

-Petra. Hello. -Hello. -May we go in? -Of course. | 0:20:07 | 0:20:12 | |

Petra, how did it come to be that George I, a German, | 0:20:12 | 0:20:16 | |

became the King of England? | 0:20:16 | 0:20:18 | |

You know, he was in line to the throne, number 58, 59, | 0:20:18 | 0:20:23 | |

but, you know, he was a Protestant, | 0:20:23 | 0:20:25 | |

and all the other pretenders were Catholics, | 0:20:25 | 0:20:29 | |

and so the English didn't want to have any Catholic on the throne. | 0:20:29 | 0:20:33 | |

So they took George I from Hanover | 0:20:33 | 0:20:39 | |

as their king in London. | 0:20:39 | 0:20:41 | |

Cos the thing that really mattered was that he wasn't a Catholic, | 0:20:41 | 0:20:44 | |

so that overrode his disadvantage of being a German? | 0:20:44 | 0:20:47 | |

Amazingly enough, yes. | 0:20:47 | 0:20:50 | |

After Duke Ernest Augustus of Hanover married Sophia, | 0:20:52 | 0:20:56 | |

granddaughter of Britain's King James I, | 0:20:56 | 0:20:58 | |

the British Act of Settlement, banning Catholics from the throne, | 0:20:58 | 0:21:01 | |

designated Sophia heiress to the British crown. | 0:21:01 | 0:21:05 | |

But after she died in 1714, her son, George, | 0:21:05 | 0:21:09 | |

became the first of five monarchs to rule over both Hanover and Britain. | 0:21:09 | 0:21:13 | |

I suppose when George I became king, he had to learn a new language. | 0:21:16 | 0:21:21 | |

He didn't speak English, not a single word, | 0:21:21 | 0:21:24 | |

so the English people couldn't believe that somebody | 0:21:24 | 0:21:27 | |

was coming from Germany who was not even able to communicate. | 0:21:27 | 0:21:32 | |

-So he NEVER learned English? -No, he did not. | 0:21:32 | 0:21:34 | |

He was the only English king who was buried outside of Great Britain. | 0:21:34 | 0:21:39 | |

-I have a guidebook here from 1913... -Mm-hm. | 0:21:39 | 0:21:43 | |

So what was the relationship between the British Royal Family | 0:21:43 | 0:21:48 | |

and the German royalty in that period? | 0:21:48 | 0:21:51 | |

You know, both monarchs were cousins. | 0:21:51 | 0:21:53 | |

Both were grandsons from Queen Victoria, | 0:21:53 | 0:21:58 | |

and here in Germany, it was Emperor William II, | 0:21:58 | 0:22:03 | |

and in England it was George V. | 0:22:03 | 0:22:05 | |

So the two countries that went to war | 0:22:05 | 0:22:08 | |

the year after my guidebook was written | 0:22:08 | 0:22:11 | |

-were ruled over by first cousins? -Yes, first cousins. | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

And they met together with the Tsar from Russia. | 0:22:14 | 0:22:18 | |

It was Nicholas II, and all three met at the marriage | 0:22:18 | 0:22:24 | |

of the Emperor's daughter on the 24th May 1913. | 0:22:24 | 0:22:29 | |

-The very time of my guidebook. -Yeah. It was the last big event | 0:22:30 | 0:22:36 | |

before the First World War started one year later. | 0:22:36 | 0:22:41 | |

-The Tsar was also related to the British Royal Family. -Yeah. | 0:22:41 | 0:22:44 | |

He was another cousin, so they were three. | 0:22:44 | 0:22:48 | |

-So George V, the Kaiser and the Tsar were all cousins? -Mm-hm. | 0:22:48 | 0:22:53 | |

-Amazing. And all involved in the war. -Ja. One year later. | 0:22:55 | 0:22:59 | |

History weighs heavily in this city. | 0:23:02 | 0:23:07 | |

The First World War was not, as hoped, the war to end all wars. | 0:23:07 | 0:23:11 | |

During the Second World War, almost all of majestic Hanover | 0:23:11 | 0:23:15 | |

was obliterated by Allied bombing. | 0:23:15 | 0:23:17 | |

After the conflict, some buildings were rebuilt from the rubble, | 0:23:17 | 0:23:21 | |

including my hotel for the night. | 0:23:21 | 0:23:24 | |

According to Bradshaw's, "German hotels are second to the Swiss, | 0:23:25 | 0:23:30 | |

"the best in the world. The cuisine is inferior only to the French, | 0:23:30 | 0:23:35 | |

"and the restaurants, superior." | 0:23:35 | 0:23:37 | |

Kastens Hotel is recommended because it has central heating, | 0:23:37 | 0:23:40 | |

and an advertisement tells me it has a motor garage and a restaurant. | 0:23:40 | 0:23:45 | |

Sounds like the place for me. | 0:23:45 | 0:23:47 | |

Kastens has served visitors to Hanover for almost 160 years, | 0:23:47 | 0:23:52 | |

and I want to find out how the hotel has changed | 0:23:52 | 0:23:54 | |

since my guidebook recommended it in 1913. | 0:23:54 | 0:23:57 | |

-Good evening. -Hello, good evening. | 0:23:57 | 0:24:00 | |

I'm using a guidebook from 1913. What was the hotel like then? | 0:24:00 | 0:24:03 | |

Well, it was like it is now, the best hotel in town, | 0:24:03 | 0:24:06 | |

and a lot of aristocrats stayed here and many travellers from England. | 0:24:06 | 0:24:12 | |

And what happened to the hotel in World War II? | 0:24:12 | 0:24:14 | |

Hanover was bombed and the hotel was also hit. | 0:24:14 | 0:24:17 | |

It was completely destroyed and the owning family then just rebuilt it | 0:24:17 | 0:24:22 | |

and we had our first rooms ready | 0:24:22 | 0:24:25 | |

for the first International Fair in 1947. | 0:24:25 | 0:24:28 | |

A wonderful effort. I'm looking forward to staying here. | 0:24:28 | 0:24:31 | |

Which room am I in? | 0:24:31 | 0:24:32 | |

Your room number is 119 on the first floor. Enjoy your stay with us. | 0:24:32 | 0:24:35 | |

-Thank you, good night. -Good night. | 0:24:35 | 0:24:38 | |

Auf Wiedersehen. | 0:24:47 | 0:24:50 | |

I'm bound next for the Ruhr Valley. | 0:24:50 | 0:24:51 | |

In 1913, it was both Germany's industrial heartland | 0:24:51 | 0:24:55 | |

and the Kaiser's arsenal. | 0:24:55 | 0:24:57 | |

I'll then push south to Cologne, detour east to experience | 0:24:57 | 0:25:01 | |

a technological marvel in Wuppertal, before journeying to the Rhineland | 0:25:01 | 0:25:05 | |

to discover the river, the vineyards that adorn its banks | 0:25:05 | 0:25:09 | |

and the cultural roots of German nationalism. | 0:25:09 | 0:25:11 | |

Germany, in common with France and Spain and Italy | 0:25:26 | 0:25:29 | |

and Japan, for that matter, | 0:25:29 | 0:25:31 | |

has a network of high-speed trains. | 0:25:31 | 0:25:35 | |

They're beautiful, they're silver, | 0:25:36 | 0:25:39 | |

they're called ICE, | 0:25:39 | 0:25:41 | |

and that spells "cool". | 0:25:41 | 0:25:44 | |

HE BLOWS WHISTLE | 0:25:44 | 0:25:45 | |

TRAIN HORN BLASTS | 0:26:01 | 0:26:03 | |

-Guten Morgen. Is this your German breakfast? -Yeah. -Wow! This looks... | 0:26:15 | 0:26:20 | |

-Beer, at this time of the day? -It's always good! | 0:26:20 | 0:26:24 | |

Always good, beer? | 0:26:24 | 0:26:26 | |

Are you celebrating, gentlemen? Is it a special occasion? | 0:26:26 | 0:26:29 | |

We have a trip to Dusseldorf. | 0:26:29 | 0:26:31 | |

Once a year, we have a trip to a city, in this case Dusseldorf. | 0:26:31 | 0:26:38 | |

Last time we were in Munich for Oktoberfest, and so on. | 0:26:38 | 0:26:42 | |

And what is that you're eating, what is this? | 0:26:42 | 0:26:44 | |

-Bratwurst. -Bratwurst? | 0:26:44 | 0:26:46 | |

-Are those gherkins? -Gurke. -You call them...? | 0:26:46 | 0:26:49 | |

-Gurke. -Gurke? Gurke, gherkins. | 0:26:49 | 0:26:52 | |

Oh, wow! You've very, very kind. Thank you very much indeed. | 0:26:52 | 0:26:56 | |

-..Sauerkraut? -Guten Appetit, hmm? | 0:26:56 | 0:26:59 | |

Mmm! | 0:26:59 | 0:27:01 | |

-Sehr gut. -It's good, yes? -Mm. | 0:27:01 | 0:27:04 | |

I can safely say this is the earliest in the morning | 0:27:05 | 0:27:08 | |

that I have ever eaten a gherkin. | 0:27:08 | 0:27:10 | |

-MEN LAUGH -It's good, it's good. | 0:27:10 | 0:27:12 | |

THEY CHATTER IN GERMAN | 0:27:12 | 0:27:15 | |

Man cannot live by gherkin alone. Time for my own breakfast. | 0:27:15 | 0:27:21 | |

-Danke. -You're welcome. -Danke. | 0:27:27 | 0:27:28 | |

I've left behind the elegant palaces of Hanover | 0:27:40 | 0:27:43 | |

and I'm heading for the traditional industrial heartland of Germany, | 0:27:43 | 0:27:47 | |

the Rhineland-Westphalia coal district, | 0:27:47 | 0:27:49 | |

which my Bradshaw's describes as "32 miles in length | 0:27:49 | 0:27:53 | |

"and 5 to 14 miles wide. | 0:27:53 | 0:27:55 | |

"One of the most productive coalfields in the world. | 0:27:55 | 0:27:58 | |

"The apparently never-ending sequence of town after town | 0:27:58 | 0:28:02 | |

"with the innumerable chimneys in all directions | 0:28:02 | 0:28:05 | |

"testify to an enormous activity." | 0:28:05 | 0:28:07 | |

By the time my guidebook was written in 1913, | 0:28:07 | 0:28:11 | |

Germany had overtaken Britain in industrial production. | 0:28:11 | 0:28:14 | |

Having been whisked along on the flagship of German railways, | 0:28:20 | 0:28:23 | |

I need to change here at Dortmund onto a slower train | 0:28:23 | 0:28:27 | |

bound for my next destination, Essen. | 0:28:27 | 0:28:29 | |

Since the 18th century, the Ruhr Valley has been synonymous | 0:28:40 | 0:28:44 | |

with the essential ingredients of industrialisation - coal and steel. | 0:28:44 | 0:28:49 | |

As Wilhelm II settled on the throne, the pits and foundries of the Ruhr | 0:28:49 | 0:28:55 | |

were expanded so fast that Essen's population | 0:28:55 | 0:28:58 | |

almost quadrupled between 1890 and 1910. | 0:28:58 | 0:29:01 | |

This was industrialisation on an unparalleled scale. | 0:29:01 | 0:29:05 | |

The collieries and steelworks may have turned the valley | 0:29:05 | 0:29:08 | |

into something resembling Dante's Inferno, | 0:29:08 | 0:29:12 | |

but they were the Kaiser's powerhouse, and in the early years | 0:29:12 | 0:29:15 | |

of the 20th century, Germany's army was war-ready. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:19 | |

Rebuilt in 1932, the Zollverein Coal Mine | 0:29:19 | 0:29:21 | |

was once the world's most modern and productive. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:26 | |

It closed in the 1980s and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site | 0:29:26 | 0:29:29 | |

and cultural centre. | 0:29:29 | 0:29:31 | |

'Christian Shroeder is a curator.' | 0:29:31 | 0:29:34 | |

-Christian, how good to see you. -Welcome. Nice to meet you. | 0:29:34 | 0:29:36 | |

It's good to see you. This is a beautiful mine museum. | 0:29:36 | 0:29:39 | |

When did mining begin in the Essen area? | 0:29:39 | 0:29:42 | |

Around about 1830. | 0:29:42 | 0:29:44 | |

All the buildings you can see all around are much younger. | 0:29:44 | 0:29:47 | |

They are from 1920 to 1932. | 0:29:47 | 0:29:49 | |

-Mining here became very extensive. -Oh, yeah. | 0:29:49 | 0:29:52 | |

The Ruhr area used to be Europe's biggest industrial area. | 0:29:52 | 0:29:54 | |

We used to cook iron and steel on 2,800 square kilometres. | 0:29:54 | 0:29:57 | |

We used to have more than 700 big coal mines. | 0:29:57 | 0:30:00 | |

And thousands of miles of tunnels? | 0:30:00 | 0:30:02 | |

Oh, yeah, thousands of them. | 0:30:02 | 0:30:04 | |

Now, this mineshaft is not only very impressive, | 0:30:04 | 0:30:06 | |

it's architecturally beautiful. | 0:30:06 | 0:30:08 | |

That's because the two young architects who built this | 0:30:08 | 0:30:11 | |

were inspired by Bauhaus architecture. | 0:30:11 | 0:30:13 | |

It was the functional Cubism of those days. | 0:30:13 | 0:30:16 | |

-May we take a look around? -Oh, sure, here we go. | 0:30:16 | 0:30:19 | |

We're getting a wonderful view of the plant now. | 0:30:22 | 0:30:24 | |

-Oh, yeah, we will. -And it's going to get better and better. | 0:30:24 | 0:30:28 | |

It's an amazing view. Tell me, at the beginning of the 20th century, | 0:30:31 | 0:30:35 | |

what would we have been able to see from here? | 0:30:35 | 0:30:38 | |

At the beginning of the 20th century, skies would've been covered with dust | 0:30:38 | 0:30:42 | |

and the streets would have been covered in ashes. | 0:30:42 | 0:30:45 | |

The horizon would have been crammed with chimneys, | 0:30:45 | 0:30:47 | |

blast furnaces, coking plants, steel mills, | 0:30:47 | 0:30:50 | |

all this, and today it's a huge green landscape, as you can see. | 0:30:50 | 0:30:56 | |

Yeah, my Bradshaw's guide tells me about the chimneys extending | 0:30:56 | 0:31:02 | |

to the horizon and also says that Krupp's huge works are here. | 0:31:02 | 0:31:07 | |

Where was Krupp's? | 0:31:07 | 0:31:09 | |

Krupp's was in this direction at the other side of the city centre. | 0:31:09 | 0:31:12 | |

And Krupp company used to be the biggest steel company here in Essen. | 0:31:12 | 0:31:17 | |

Essen is associated with the family Krupp | 0:31:17 | 0:31:20 | |

and Krupp is always associated with Essen. | 0:31:20 | 0:31:22 | |

Yes, it's interesting, isn't it, | 0:31:22 | 0:31:23 | |

that my English Bradshaw's guide in 1913 says, "Krupp" - | 0:31:23 | 0:31:27 | |

it doesn't have to say steel, Krupp MEANT steel. | 0:31:27 | 0:31:30 | |

Yes. It's a legend in Germany - Krupp. | 0:31:30 | 0:31:32 | |

He was one of the first industrial pioneers | 0:31:32 | 0:31:35 | |

and he made German steel what it became later on. | 0:31:35 | 0:31:37 | |

He was a maniac in cooking steel. | 0:31:37 | 0:31:39 | |

He slept in his workshop, he lived in his workshop - | 0:31:39 | 0:31:42 | |

all he was doing was cooking steel 24 hours a day. | 0:31:42 | 0:31:45 | |

In 1852, industrialist Alfred Krupp | 0:31:45 | 0:31:48 | |

invented the seamless steel railway tyre which made him his fortune. | 0:31:48 | 0:31:53 | |

His passion for steel and profit then propelled him | 0:31:53 | 0:31:57 | |

into the arms business. | 0:31:57 | 0:31:58 | |

By the time of his death, he had armed 46 nations, | 0:31:58 | 0:32:02 | |

and in the run-up to the First World War, | 0:32:02 | 0:32:05 | |

his company would arm Germany, | 0:32:05 | 0:32:06 | |

earning Krupp the moniker the Arsenal of the Reich. | 0:32:06 | 0:32:09 | |

Modern Germany is a peace-loving country. | 0:32:11 | 0:32:14 | |

The Ruhr's chimneys have been felled. | 0:32:14 | 0:32:17 | |

Zollverein now pursues seams of culture rather than coal. | 0:32:17 | 0:32:20 | |

Bravo! | 0:32:53 | 0:32:55 | |

Thank you, that was wonderful. | 0:32:55 | 0:32:57 | |

Back to Essen Central to catch a connection to my next destination - | 0:33:01 | 0:33:04 | |

Cologne. | 0:33:04 | 0:33:06 | |

No good. My German's not up to it. | 0:33:12 | 0:33:14 | |

I'll stick to my Bradshaw's. | 0:33:14 | 0:33:17 | |

Bradshaw's tells me that my next destination, Cologne, | 0:33:21 | 0:33:25 | |

lies on the left bank of the River Rhine. "It's an imperial fortress, | 0:33:25 | 0:33:29 | |

"the largest town of the Rhine Provinces of Prussia." | 0:33:29 | 0:33:33 | |

Having thrown off the rust and dust | 0:33:33 | 0:33:35 | |

of the Ruhr in the 19th and 20th centuries, | 0:33:35 | 0:33:37 | |

I'm looking forward to seeing the wonderful medieval cathedral | 0:33:37 | 0:33:40 | |

in Cologne. | 0:33:40 | 0:33:42 | |

ARRIVAL ANNOUNCEMENT ON TRAIN'S PA | 0:33:42 | 0:33:45 | |

The oldest large town in Germany, | 0:33:51 | 0:33:53 | |

Cologne sits astride the mighty Rhine. | 0:33:53 | 0:33:57 | |

With six million visitors a year, | 0:33:57 | 0:34:00 | |

its Cathedral is Germany's most popular place of interest. | 0:34:00 | 0:34:03 | |

Its towers, added in the 19th century | 0:34:03 | 0:34:05 | |

have dominated the city's skyline since their completion in 1880. | 0:34:05 | 0:34:09 | |

The way they built the railway next to the cathedral in Cologne | 0:34:11 | 0:34:15 | |

means that the view you get on leaving this station | 0:34:15 | 0:34:17 | |

must have very few rivals anywhere in Europe. | 0:34:17 | 0:34:20 | |

In 1164, Archbishop Rainald von Dassel brought to Cologne | 0:34:25 | 0:34:29 | |

from the vanquished city of Milan what he and the devout believed | 0:34:29 | 0:34:33 | |

to be the remains of the Three Kings, who visited the baby Jesus. | 0:34:33 | 0:34:37 | |

The Gothic cathedral was a fittingly grand building | 0:34:39 | 0:34:42 | |

that impressed pilgrims paying homage to the Magi. | 0:34:42 | 0:34:44 | |

Measuring almost 8,000 square metres, | 0:34:51 | 0:34:54 | |

with space for 4,000 worshippers | 0:34:54 | 0:34:56 | |

it's one of Germany's true architectural glories. | 0:34:56 | 0:34:59 | |

I'm hugely impressed by the cathedral | 0:35:03 | 0:35:05 | |

which my Bradshaw's tells me | 0:35:05 | 0:35:07 | |

"is sometimes described as the most magnificent Gothic edifice in the world." | 0:35:07 | 0:35:12 | |

I now want to do something which, in my guide, comes highly recommended - | 0:35:13 | 0:35:17 | |

a visit to Johann Maria Farina at 4 Julich-Platz for Eau de Cologne. | 0:35:17 | 0:35:23 | |

In the 18th century, perfume was big business | 0:35:27 | 0:35:30 | |

because filthy, sewerless cities led to foul odours, | 0:35:30 | 0:35:33 | |

whilst polluted water discouraged regular ablutions. | 0:35:33 | 0:35:37 | |

In Cologne, Italian immigrant Johann Maria Farina | 0:35:39 | 0:35:41 | |

transformed the industry | 0:35:41 | 0:35:43 | |

by distilling pure alcohol to produce lighter, | 0:35:43 | 0:35:46 | |

less sticky, and more fragrant perfumes. | 0:35:46 | 0:35:49 | |

His signature scent was Eau de Cologne. | 0:35:49 | 0:35:52 | |

Johann Maria Farina, I presume. | 0:35:56 | 0:35:58 | |

Ah, buongiorno. Benvenuti alla mia casa. | 0:36:00 | 0:36:03 | |

Very good to see you. | 0:36:03 | 0:36:04 | |

So, who was Johann Maria Farina? | 0:36:04 | 0:36:07 | |

He basically was an Italian perfume-maker who came to Cologne | 0:36:07 | 0:36:10 | |

about 300 years ago, | 0:36:10 | 0:36:12 | |

and he invented a perfume which he then called Eau de Cologne. | 0:36:12 | 0:36:15 | |

This perfume created by an Italian in Germany, | 0:36:15 | 0:36:18 | |

did it still have a very strong Italian accent to it? | 0:36:18 | 0:36:22 | |

It did, yes. Basically, Farina must have missed his native land of Italy, | 0:36:22 | 0:36:26 | |

so he tried to create a perfume which reminded him of Italy. | 0:36:26 | 0:36:31 | |

You need to understand that, in his days, | 0:36:31 | 0:36:32 | |

Cologne was a very smelly city. The city altogether was, | 0:36:32 | 0:36:36 | |

and also the people themselves didn't really wash | 0:36:36 | 0:36:39 | |

because they were afraid the water would spread diseases and all sorts. | 0:36:39 | 0:36:42 | |

Did it become an immediate success? | 0:36:42 | 0:36:44 | |

Yes, it did, very, very soon, yes. | 0:36:44 | 0:36:46 | |

Because it was so different to other perfumes which were there before. | 0:36:46 | 0:36:52 | |

Basically, what you got were very heavy-smelling perfumes. | 0:36:52 | 0:36:56 | |

Then it was all of a sudden a very light, refreshing perfume. | 0:36:56 | 0:37:00 | |

-Was it for men or for women? -Both. Unisex, it was. | 0:37:00 | 0:37:03 | |

What sort of people were able to buy perfume in those days? | 0:37:03 | 0:37:06 | |

Not many. It was very, very expensive. | 0:37:06 | 0:37:08 | |

In today's terms, maybe 2,000 euro per bottle. | 0:37:08 | 0:37:11 | |

What sorts of people were the clients of Eau de Cologne? | 0:37:11 | 0:37:14 | |

In Cologne, you've got famous Prince Elector Clemens August | 0:37:14 | 0:37:18 | |

who bought 40 bottles in a month. | 0:37:18 | 0:37:21 | |

And also French emperor Napoleon used one bottle a day for private purpose. | 0:37:21 | 0:37:27 | |

And Napoleon actually had himself made special boots, | 0:37:27 | 0:37:30 | |

into the back of which he could hide one bottle of Eau de Cologne. | 0:37:30 | 0:37:33 | |

So that even when he was sitting on a horse | 0:37:33 | 0:37:36 | |

he could secretly use Eau de Cologne. | 0:37:36 | 0:37:38 | |

You've lots of intriguing bottles here. Any that I can sniff? | 0:37:38 | 0:37:41 | |

Yeah, sure. This, for example, is a heavy smell. | 0:37:41 | 0:37:45 | |

Something people used before Farina came to Cologne. | 0:37:45 | 0:37:47 | |

Be careful. Just do a bit of hand waving, because it is very strong. | 0:37:47 | 0:37:51 | |

That IS very, very strong. | 0:37:53 | 0:37:55 | |

So, if I mix that with body odour and sewage... | 0:37:55 | 0:37:58 | |

And not washing for a couple of months, | 0:37:58 | 0:38:00 | |

then you can imagine what people smelled like - horrible! | 0:38:00 | 0:38:03 | |

This is a light fragrance. Something people would not have had before the 1700s. | 0:38:03 | 0:38:08 | |

Totally different story. | 0:38:10 | 0:38:13 | |

-Ah...um...grapefruit. -Yes! Grapefruit! Indeed. Well done. | 0:38:13 | 0:38:16 | |

See if you can guess which one that is? | 0:38:16 | 0:38:18 | |

That's a lovely fragrance. Um... | 0:38:20 | 0:38:22 | |

What is that? | 0:38:22 | 0:38:24 | |

It's what we call amber. | 0:38:24 | 0:38:25 | |

Amber is actually made from the intestines of the sperm whale. | 0:38:25 | 0:38:28 | |

Given that, it smells quite good. | 0:38:28 | 0:38:30 | |

In over 300 years, only 30 people | 0:38:32 | 0:38:35 | |

have been entrusted with the secret recipe of Farina's Eau de Cologne. | 0:38:35 | 0:38:40 | |

The current Johann Maria Farina is one of them. | 0:38:40 | 0:38:43 | |

Is the recipe today the same the same as it was? | 0:38:44 | 0:38:47 | |

Yes. The recipe was always kept secret and always kept the same way. | 0:38:47 | 0:38:52 | |

Tell me about the great British clients of your firm. | 0:38:52 | 0:38:56 | |

From the late 18th century on, we delivered to England, or London. | 0:38:56 | 0:39:01 | |

Also the Queens and Kings in London bought this product from us, | 0:39:01 | 0:39:05 | |

and from Queen Victoria onwards we have been purveyor of the court. | 0:39:05 | 0:39:10 | |

Queen Victoria - what did she like to buy? | 0:39:10 | 0:39:13 | |

She bought the original Eau de Cologne. | 0:39:13 | 0:39:15 | |

She knew this product from childhood, on. | 0:39:15 | 0:39:17 | |

And an average order of 60 dozen was not unusual. | 0:39:17 | 0:39:21 | |

I'm leaving Cologne, bound for my next destination, | 0:39:31 | 0:39:34 | |

and I wonder what my fellow passengers will make | 0:39:34 | 0:39:37 | |

of Farina's 18th-century scent. | 0:39:37 | 0:39:40 | |

Excuse me. | 0:39:40 | 0:39:42 | |

I've got some Eau de Cologne here, can I just test it on you? | 0:39:42 | 0:39:45 | |

Do you think that's for a man or a woman? | 0:39:48 | 0:39:51 | |

-Both. -Really? Both. | 0:39:51 | 0:39:53 | |

Would you like to try this Eau de Cologne? | 0:39:58 | 0:40:00 | |

-OK, now I can...? -Mm-hm. | 0:40:02 | 0:40:04 | |

What do you think of that? | 0:40:04 | 0:40:06 | |

It's a nice perfume but I think it's a girl perfume. | 0:40:06 | 0:40:09 | |

When do you wear a scent? | 0:40:09 | 0:40:10 | |

When I shave, then I do this aftershave. | 0:40:10 | 0:40:12 | |

-You like to smell good? -Yes, nice. | 0:40:12 | 0:40:14 | |

-And your girlfriend likes you to smell good? -Yes. One of them. | 0:40:14 | 0:40:19 | |

-One of them! -THEY LAUGH | 0:40:19 | 0:40:20 | |

You're very trusting. | 0:40:25 | 0:40:27 | |

-What do you think of that? -It's very nice. It's not too strong. | 0:40:27 | 0:40:32 | |

-Would you wear it yourself? -Yes. I think so, yes. | 0:40:32 | 0:40:35 | |

-Have a good journey. Where are you going to? -I'm going to Wuppertal. | 0:40:35 | 0:40:38 | |

Wuppertal! I'm going there too. Maybe I'll see you there. | 0:40:38 | 0:40:40 | |

-I hope so. Have a nice day. -Bye. -Bye. | 0:40:40 | 0:40:43 | |

Before I leave Germany's industrial heartland | 0:40:49 | 0:40:52 | |

my Bradshaw's draws my attention to Elberfeld and Barmen, | 0:40:52 | 0:40:56 | |

"with several suburbs, they are practically one large industrial town, | 0:40:56 | 0:41:00 | |

"stretching along the valley of the Wupper and up the side slopes." | 0:41:00 | 0:41:04 | |

Those areas have now been consolidated in Wuppertal, | 0:41:04 | 0:41:07 | |

and I'm attracted there | 0:41:07 | 0:41:09 | |

because of its special place in railway history. | 0:41:09 | 0:41:13 | |

At the turn of the 20th century, | 0:41:15 | 0:41:17 | |

as Germany's industrial output soared | 0:41:17 | 0:41:19 | |

and workers flooded into the Ruhr Valley, | 0:41:19 | 0:41:22 | |

those who settled in Elberfeld and Barmen | 0:41:22 | 0:41:24 | |

needed a transport system to get them to and from their factories. | 0:41:24 | 0:41:28 | |

The answer was typically German - | 0:41:28 | 0:41:31 | |

modern, pragmatic and perfectly engineered. | 0:41:31 | 0:41:34 | |

The 13km Schwebebahn, a unique suspended railway, known locally | 0:41:35 | 0:41:40 | |

as the Old Lady, began running in 1901. | 0:41:40 | 0:41:44 | |

My guide is Melanie Schoeppe. | 0:41:44 | 0:41:46 | |

Why did they build THIS sort of railway here? | 0:41:50 | 0:41:53 | |

Why not a conventional one? | 0:41:53 | 0:41:55 | |

Because we have a very rocky subsoil | 0:41:55 | 0:41:58 | |

and so we had to build a railway over the Wupper river. | 0:41:58 | 0:42:01 | |

-You couldn't build one underground? -No, it's not possible. | 0:42:01 | 0:42:05 | |

I imagined it was going to be a kind of museum railway, | 0:42:05 | 0:42:08 | |

but, actually, it's well used by the public. | 0:42:08 | 0:42:10 | |

Yes. About 18,000 people use the train daily. | 0:42:10 | 0:42:13 | |

Something I'm not used to is that | 0:42:13 | 0:42:16 | |

I can see into everybody's window. I can see into everybody's house. | 0:42:16 | 0:42:20 | |

Do the people feel OK about that? | 0:42:20 | 0:42:22 | |

At the beginning of the century there were many religious groups | 0:42:22 | 0:42:27 | |

which protested vigorously against the Iron Dragon, | 0:42:27 | 0:42:29 | |

as they called the suspension railway. | 0:42:29 | 0:42:32 | |

But today people are used to it. | 0:42:32 | 0:42:34 | |

So they thought they'd see into people's bedrooms - which you can! | 0:42:34 | 0:42:38 | |

'The Schweberbahn runs a non-stopping service | 0:42:41 | 0:42:44 | |

'aboard a very historic carriage, dispensing cheesecake and coffee.' | 0:42:44 | 0:42:49 | |

This is going to be great! | 0:42:49 | 0:42:51 | |

The railway welcomes passengers aboard its Kaiserwagen, | 0:42:59 | 0:43:02 | |

the very train that carried Emperor Wilhelm II | 0:43:02 | 0:43:06 | |

on the day that he came to open the line, | 0:43:06 | 0:43:08 | |

which represented his country's latest engineering triumph. | 0:43:08 | 0:43:13 | |

More than 100 years later, | 0:43:13 | 0:43:15 | |

as I'm whisked along on this unique suspended monorail, | 0:43:15 | 0:43:17 | |

I can readily appreciate the pride he felt. | 0:43:17 | 0:43:20 | |

I'm now extending my Bradshaw's recommended routes | 0:43:32 | 0:43:36 | |

to travel to the region of the Rhine - | 0:43:36 | 0:43:38 | |

an area that, at the beginning of the 20th century, | 0:43:38 | 0:43:41 | |

was immensely popular with tourists | 0:43:41 | 0:43:43 | |

but at that time its railways were important for another reason too - | 0:43:43 | 0:43:48 | |

for the transport of soldiers and guns. | 0:43:48 | 0:43:53 | |

My 1913 Bradshaw's tells me that on a war-footing, Germany has an army of three million. | 0:43:59 | 0:44:03 | |

Not information that I'd expect to find in a modern guidebook. | 0:44:03 | 0:44:08 | |

Before I get to my overnight stay at Koblenz, | 0:44:09 | 0:44:12 | |

'I'm meeting military historian Dr Rainer Mertens | 0:44:12 | 0:44:15 | |

'to learn of the railways' central role in Germany's war-readiness.' | 0:44:15 | 0:44:18 | |

How early on do you think it was appreciated | 0:44:19 | 0:44:22 | |

that the railways could be helpful to armies? | 0:44:22 | 0:44:24 | |

I think in Germany it started with the revolution in 1848, | 0:44:24 | 0:44:27 | |

where Prussian troops were moved, | 0:44:27 | 0:44:30 | |

were transported, to defeat the revolutionaries. | 0:44:30 | 0:44:34 | |

My guidebook is from 1913 - now, what plans were in place in 1913 | 0:44:34 | 0:44:40 | |

for the use of the railways in wartime? | 0:44:40 | 0:44:43 | |

In the years before the First World War, | 0:44:43 | 0:44:45 | |

General Schlieffen developed a plan first to defeat France in the west | 0:44:45 | 0:44:51 | |

with seven-eighths of all German troops | 0:44:51 | 0:44:53 | |

and then after defeating the French troops, | 0:44:53 | 0:44:56 | |

bringing back the troops to the east and fighting against Russia. | 0:44:56 | 0:45:02 | |

Now, that Schlieffen Plan must have depended heavily, | 0:45:02 | 0:45:06 | |

-entirely on railways. -Absolutely. | 0:45:06 | 0:45:09 | |

And you have to imagine when the war broke out at 2nd August | 0:45:09 | 0:45:13 | |

and up to the 14th August, | 0:45:13 | 0:45:15 | |

they transported over three million soldiers by 11,000 trains. | 0:45:15 | 0:45:20 | |

There were some very famous railway guns, weren't there? | 0:45:20 | 0:45:23 | |

We in Britain have heard of Big Bertha. | 0:45:23 | 0:45:25 | |

They constructed weapon guns that were very heavy, | 0:45:25 | 0:45:29 | |

like they could shoot about 60 or 70 miles. | 0:45:29 | 0:45:33 | |

It was almost like a rocket. | 0:45:33 | 0:45:35 | |

Generally, you can say that WWI was a railway war | 0:45:35 | 0:45:38 | |

because all that strategy was based on the railways. | 0:45:38 | 0:45:42 | |

More than ever before were killed | 0:45:42 | 0:45:44 | |

and the next were brought to the battlefields. | 0:45:44 | 0:45:47 | |

And so millions and millions lost their lives | 0:45:47 | 0:45:51 | |

and this was only possible by the railway. | 0:45:51 | 0:45:54 | |

After World War I, a vanquished Germany | 0:45:55 | 0:45:59 | |

yielded some of its outlying territories, towns and cities. | 0:45:59 | 0:46:03 | |

For more than ten years after the armistice, Koblenz in the Rhineland | 0:46:03 | 0:46:07 | |

was held by France. | 0:46:07 | 0:46:09 | |

But that was unforeseeable in 1913. | 0:46:09 | 0:46:13 | |

My Bradshaw's says that Koblenz | 0:46:19 | 0:46:21 | |

is the capital of the Rhinish province of Prussia, | 0:46:21 | 0:46:24 | |

picturesquely situated at the confluence | 0:46:24 | 0:46:26 | |

of the rivers Rhine and Mosel. | 0:46:26 | 0:46:28 | |

And since the names of both those rivers make me think of wine, | 0:46:28 | 0:46:32 | |

this could be a good place to spend the night. | 0:46:32 | 0:46:34 | |

And I bet the food's not bad either. | 0:46:34 | 0:46:37 | |

Good evening. Looks like a lovely restaurant. | 0:46:50 | 0:46:53 | |

Thank you. | 0:47:00 | 0:47:02 | |

-The asparagus looks wonderful. -Yes. -Thank you. | 0:47:02 | 0:47:05 | |

-Guten Appetit! -Thank you very much. | 0:47:05 | 0:47:07 | |

German asparagus in season. | 0:47:10 | 0:47:13 | |

Heaven! | 0:47:13 | 0:47:15 | |

After a splendid evening, I've woken in the Rhineland. | 0:47:31 | 0:47:34 | |

My Bradshaw's says, "Vine-clad hills, rugged peaks, | 0:47:34 | 0:47:38 | |

"ruined castles and modern stately dwellings | 0:47:38 | 0:47:41 | |

"with the glamour of history and legend clinging to many a scene." | 0:47:41 | 0:47:47 | |

I'm now in the region of the Rhine castles - | 0:47:57 | 0:47:59 | |

a mixture of authentic Medieval ruins | 0:47:59 | 0:48:02 | |

and 19th-century Gothic restorations, | 0:48:02 | 0:48:04 | |

and a favourite with Edwardian travellers. | 0:48:04 | 0:48:07 | |

I'm heading for one recommended by my 1913 guidebook. | 0:48:14 | 0:48:18 | |

Bradshaw's tells me that Stolzenfels Castle | 0:48:18 | 0:48:22 | |

"is on the wooded heights above the river. | 0:48:22 | 0:48:24 | |

"It's the property of the Emperor and can be visited." | 0:48:24 | 0:48:27 | |

And it helpfully suggests that I can take a donkey. | 0:48:27 | 0:48:30 | |

There don't seem to be any around, so it will have to be shanks' pony. | 0:48:30 | 0:48:34 | |

The French often conquered the Rhineland, | 0:48:37 | 0:48:40 | |

destroying castles in their path. | 0:48:40 | 0:48:43 | |

But in the early 19th century, Prussia won it back | 0:48:43 | 0:48:46 | |

and Crown Prince Freidrich Wilhelm | 0:48:46 | 0:48:48 | |

decided to rebuild Stolzenfels, | 0:48:48 | 0:48:50 | |

once a bishop's seat, as his summer residence. | 0:48:50 | 0:48:54 | |

Queen Victoria visited her cousin's new castle. | 0:48:54 | 0:48:57 | |

And in the early 20th century, so did many Edwardian tourists. | 0:48:57 | 0:49:01 | |

Historian Angela Kaiser-Lahme | 0:49:02 | 0:49:04 | |

was involved in Stolzenfels' most recent restoration. | 0:49:04 | 0:49:08 | |

The castle is in beautiful condition. | 0:49:09 | 0:49:12 | |

Yes. We had it restored in the recent years | 0:49:12 | 0:49:15 | |

and it's now looking as it has in the 1840s. | 0:49:15 | 0:49:17 | |

Presumably this has been many, many years' work. | 0:49:17 | 0:49:22 | |

Oh, yes. Basically, six to eight years. | 0:49:22 | 0:49:25 | |

And a wonderful view, of course, over the Rhine. | 0:49:25 | 0:49:28 | |

Well, that is lovely. | 0:49:30 | 0:49:32 | |

Oh, yes, indeed it is. | 0:49:32 | 0:49:35 | |

Many visitors are saying the same thing. | 0:49:35 | 0:49:37 | |

Angela, you see so many castles on the Rhine River, | 0:49:37 | 0:49:40 | |

how many are there, or were there? | 0:49:40 | 0:49:43 | |

In between Koblenz and Bingen, there are said to be more than 40. | 0:49:43 | 0:49:47 | |

So every ten kilometres or sometimes less than ten kilometres, | 0:49:47 | 0:49:52 | |

you find a castle or two. | 0:49:52 | 0:49:54 | |

Why were there so many? | 0:49:54 | 0:49:56 | |

The Rhine was the main transport route in the Middle Ages. | 0:49:56 | 0:49:59 | |

So every good was transported over the Rhine. | 0:49:59 | 0:50:02 | |

And that means much income for those | 0:50:02 | 0:50:04 | |

who could draw the taxes from all these goods. | 0:50:04 | 0:50:07 | |

And was Stolzenfels built for that reason? | 0:50:07 | 0:50:10 | |

Yes. It was more or less a custom station. | 0:50:10 | 0:50:13 | |

And the Bishop of Trier | 0:50:13 | 0:50:15 | |

took quite a lot of his income from these taxes. | 0:50:15 | 0:50:18 | |

The powerful Rhineland magnates became known as Robber Barons. | 0:50:18 | 0:50:22 | |

But during the 19th century, their castles provided the backdrop | 0:50:22 | 0:50:26 | |

for a new artistic movement called the Romantics, | 0:50:26 | 0:50:29 | |

whose patriotism drew inspiration | 0:50:29 | 0:50:31 | |

from fables of the Middle Ages, | 0:50:31 | 0:50:33 | |

celebrating the glories of German culture. | 0:50:33 | 0:50:36 | |

Richard Wagner set his opera about the dragon-slayer Siegfried | 0:50:36 | 0:50:39 | |

on the Rhine. By the time of my 1913 guidebook, | 0:50:39 | 0:50:43 | |

Britain was intensely worried | 0:50:43 | 0:50:46 | |

that German nationalism had become aggressive, | 0:50:46 | 0:50:49 | |

and Europe feared war. | 0:50:49 | 0:50:52 | |

So you get romanticism, you get Richard Wagner, | 0:50:52 | 0:50:54 | |

you get the rebuilding of some of the Rhine castles | 0:50:54 | 0:50:56 | |

and you get German nationalism at the same time. | 0:50:56 | 0:50:59 | |

When Stolzenfels was rebuilt, and that was about 1842, | 0:50:59 | 0:51:03 | |

nationalism was young. And it had a different drive. | 0:51:03 | 0:51:07 | |

It was more patriotism, more romantic. | 0:51:07 | 0:51:10 | |

At the end of the 19th century, | 0:51:10 | 0:51:11 | |

Germany wanted to play in the same league as Great Britain and France. | 0:51:11 | 0:51:16 | |

And this patriotism really became nationalism. | 0:51:16 | 0:51:20 | |

The Rhine's steep slopes and eerie ruins | 0:51:21 | 0:51:24 | |

inspired enduring German myths. | 0:51:24 | 0:51:26 | |

Just like a traveller in 1913, | 0:51:26 | 0:51:29 | |

I feel dragons and seductive Rhine sprites always close at hand. | 0:51:29 | 0:51:34 | |

Bradshaw's says, "The River Rhine is abundantly interesting. | 0:51:35 | 0:51:39 | |

"From its impetuous source | 0:51:39 | 0:51:41 | |

"to its sluggish meeting with the sea." | 0:51:41 | 0:51:44 | |

I think it's one of the great rivers of the world. | 0:51:44 | 0:51:47 | |

And the way to experience it is afloat. | 0:51:47 | 0:51:50 | |

My final destination is downriver at Rheingau. | 0:51:50 | 0:51:54 | |

What better way to get there than on a beautiful paddle steamer | 0:51:59 | 0:52:03 | |

built in 1913 - the year that my guidebook was published? | 0:52:03 | 0:52:07 | |

It lists the times of train arrivals and steamer departures | 0:52:07 | 0:52:10 | |

to help rail passengers to plan a smooth journey. | 0:52:10 | 0:52:13 | |

When on The Rhine, eat as Rhinelanders do. | 0:52:20 | 0:52:23 | |

-Hello. May I join you? -Yes. | 0:52:34 | 0:52:37 | |

Isn't it wonderful today? What a lovely view! | 0:52:37 | 0:52:39 | |

It's lovely. It's a dream. | 0:52:39 | 0:52:42 | |

-What do you think of the ship? -I think there are more modern ones, | 0:52:42 | 0:52:45 | |

but this is one a beautiful, comfortable ship. | 0:52:45 | 0:52:48 | |

I chose this ship because I'm using a 1913 guidebook. | 0:52:48 | 0:52:52 | |

Ah, that's interesting. | 0:52:52 | 0:52:54 | |

This ship is from the beginning of the 20th century. | 0:52:54 | 0:52:56 | |

I can tell you the time of all the steamers in 1913! | 0:52:56 | 0:53:01 | |

THEY LAUGH | 0:53:01 | 0:53:02 | |

This is amazing. | 0:53:02 | 0:53:04 | |

Coming from England, and I know nothing. | 0:53:04 | 0:53:07 | |

THEY LAUGH | 0:53:07 | 0:53:09 | |

My Bradshaw's draws attention to a famous wine-producing district | 0:53:12 | 0:53:16 | |

extending from a little west of Rudesheim to Eltville. | 0:53:16 | 0:53:20 | |

At the beginning of the 20th century, | 0:53:20 | 0:53:23 | |

Rhine wines were particularly prized by British connoisseurs. | 0:53:23 | 0:53:26 | |

And I've no reason to believe | 0:53:26 | 0:53:29 | |

that they're any less deserving of admiration today. | 0:53:29 | 0:53:33 | |

In late 20th-century Britain, German wine fell from fashion. | 0:53:34 | 0:53:39 | |

But for the Edwardians, | 0:53:39 | 0:53:41 | |

Riesling, made from grapes grown on the banks of the Rhine, | 0:53:41 | 0:53:44 | |

was very popular, and known simply as hock. | 0:53:44 | 0:53:47 | |

This has to be one of the loveliest views in Europe. | 0:53:49 | 0:53:53 | |

Well, it's certainly a very special place here in the Rhine Valley, | 0:53:53 | 0:53:56 | |

with this fantastic view of the river and the whole landscape. | 0:53:56 | 0:54:01 | |

Dieter Greiner is managing director at Kloster Eberbach, | 0:54:03 | 0:54:06 | |

sited in an ancient Cistercian monastery, | 0:54:06 | 0:54:10 | |

whose monks planted vines here 800 years ago. | 0:54:10 | 0:54:12 | |

Why are these slopes here so good for wine? | 0:54:15 | 0:54:18 | |

Well, first of all, we are very much north. | 0:54:18 | 0:54:20 | |

We are on the 50th parallel. | 0:54:20 | 0:54:22 | |

And you see down there the Rhine River. It's over a kilometre wide. | 0:54:22 | 0:54:26 | |

It keeps the warmth here in winter, and in summer, it really cools down. | 0:54:26 | 0:54:30 | |

So in winter, it's never too cold, in summer, never too hot. | 0:54:30 | 0:54:33 | |

At the beginning of the 20th century particularly, | 0:54:33 | 0:54:36 | |

Riesling was very popular in the United Kingdom. | 0:54:36 | 0:54:38 | |

And it was called hock. Why was it called hock? | 0:54:38 | 0:54:41 | |

Well, your Queen Victoria visited a village called Hochheim | 0:54:41 | 0:54:46 | |

and she was presented a wine from this village and she loved it a lot. | 0:54:46 | 0:54:50 | |

And then she made this wine very popular in the UK. | 0:54:50 | 0:54:54 | |

And then the British called this wine from Hochheim, with abbreviation, just hock. | 0:54:54 | 0:54:58 | |

So this is the bedroom of the monks. | 0:55:03 | 0:55:06 | |

It's the most beautiful space. | 0:55:06 | 0:55:08 | |

It was obviously a big abbey. There were a lot of monks. | 0:55:08 | 0:55:11 | |

Oh, yes. About 60 monks on average. | 0:55:11 | 0:55:13 | |

But sometimes even up to 120. | 0:55:13 | 0:55:16 | |

And all these monks were sleeping in here. | 0:55:16 | 0:55:18 | |

Just imagine the snoring sound at night! | 0:55:18 | 0:55:20 | |

-After they'd drunk their Riesling. -Well, they certainly had their share. | 0:55:20 | 0:55:24 | |

-Here we are. -It's wonderful! | 0:55:32 | 0:55:35 | |

You obviously have some wonderful wines here. | 0:55:35 | 0:55:38 | |

What would be the oldest that you have? | 0:55:38 | 0:55:41 | |

Well, in fact, the oldest bottles date back to the year 1706. | 0:55:41 | 0:55:44 | |

1706! That's incredible! | 0:55:44 | 0:55:46 | |

And valuable wines, too. What's the most valuable? | 0:55:46 | 0:55:49 | |

The most expensive bottle is about £18,000 we have in here. | 0:55:49 | 0:55:54 | |

Extraordinary! | 0:55:54 | 0:55:55 | |

I always ask people, were the railways used in this business? | 0:55:55 | 0:55:59 | |

There was one very important transportation of wine | 0:55:59 | 0:56:02 | |

when the Duke of Nassau took the wrong side | 0:56:02 | 0:56:05 | |

on the war of the Prussians against the Austrians. | 0:56:05 | 0:56:08 | |

And so he had to leave. | 0:56:08 | 0:56:10 | |

And all the wines were evacuated overnight | 0:56:10 | 0:56:12 | |

and all put on a railway wagon and taken into exile. | 0:56:12 | 0:56:15 | |

I'm sure they would have been entirely safe on German railways. | 0:56:15 | 0:56:19 | |

And how long would a wine like this keep, by the way? | 0:56:19 | 0:56:22 | |

Well, 150, 200 years minimum. | 0:56:22 | 0:56:25 | |

Really? | 0:56:25 | 0:56:28 | |

So you could still drink some wine from the 19th century? | 0:56:28 | 0:56:31 | |

The best vintages, yes, of course. They are almost ageless. | 0:56:31 | 0:56:34 | |

What might we sample today? | 0:56:34 | 0:56:36 | |

Well, I think what would be very interesting is a dry style Riesling, | 0:56:36 | 0:56:41 | |

which is the original style of Riesling. | 0:56:41 | 0:56:45 | |

Maestro, you'll need your instrument. | 0:56:45 | 0:56:48 | |

Not this time. We use screw caps. | 0:56:48 | 0:56:50 | |

THEY LAUGH | 0:56:50 | 0:56:51 | |

Smells good to me. How is it? | 0:56:59 | 0:57:01 | |

It has dried apricots, it has this bit of hay, fresh-cut hay. | 0:57:01 | 0:57:06 | |

The body's not rich. It's a medium body and a great length. | 0:57:08 | 0:57:11 | |

This wonderful crisp acidity, but not too acidic, just fresh. | 0:57:11 | 0:57:15 | |

And it's a wonderful wine which makes you want more. | 0:57:15 | 0:57:19 | |

-That's what -I -meant to say. | 0:57:19 | 0:57:20 | |

Yes. I like it very much. | 0:57:27 | 0:57:30 | |

Edwardians flocked to Germany because they loved its landscape | 0:57:32 | 0:57:36 | |

and admired its science and industry. | 0:57:36 | 0:57:40 | |

Queen Victoria enjoyed this scenery from her railway carriage. | 0:57:40 | 0:57:43 | |

Yet our two countries went to war, spilling the blood of generations. | 0:57:43 | 0:57:48 | |

Thankfully, in the modern world, | 0:57:48 | 0:57:50 | |

we've rediscovered the bonds that we took for granted | 0:57:50 | 0:57:53 | |

when my Bradshaw's Guide was published. | 0:57:53 | 0:57:56 | |

On my next journey, I'll explore Switzerland, | 0:58:00 | 0:58:04 | |

whose remarkable railways made it a favourite with Edwardian tourists. | 0:58:04 | 0:58:09 | |

I've been lucky enough to experience some very beautiful train journeys, | 0:58:09 | 0:58:12 | |

but this one must be one of the very best. | 0:58:12 | 0:58:15 | |

I'll immerse myself in literature. | 0:58:15 | 0:58:17 | |

Do you remember any Sherlock Holmes stories? | 0:58:17 | 0:58:20 | |

HE HOWLS | 0:58:20 | 0:58:22 | |

And see how great engineering feats | 0:58:22 | 0:58:24 | |

conquered the most challenging peaks. | 0:58:24 | 0:58:27 | |

That is awe-inspiring! | 0:58:27 | 0:58:30 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:58:38 | 0:58:40 |