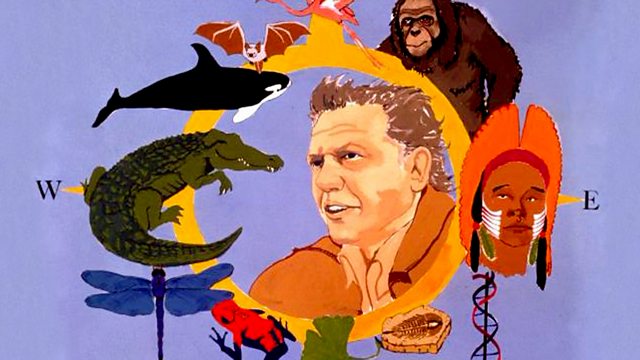

Themes and Variations Life on Earth

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Themes and Variations. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Although all those creatures are different, | 0:01:12 | 0:01:14 | |

they are in fact closely related to one another. They are all mammals. | 0:01:14 | 0:01:19 | |

But how have they become so varied? | 0:01:19 | 0:01:22 | |

And what is the ancestral form, the basic theme, on which they are all variations? | 0:01:22 | 0:01:27 | |

You can find a close approximation to that theme in the jungles of South-East Asia. | 0:01:27 | 0:01:33 | |

It's properly called a tupaia, | 0:01:35 | 0:01:37 | |

and it's certainly a mammal, with a hairy coat and warm blood. | 0:01:37 | 0:01:40 | |

But what kind? It looks very like a squirrel. | 0:01:40 | 0:01:44 | |

A close look at its anatomy reveals resemblances to a rabbit, | 0:01:44 | 0:01:48 | |

but it doesn't gnaw nuts and it doesn't nibble grass, it catches insects. | 0:01:48 | 0:01:53 | |

Its teeth are small, numerous and spiky, like a shrew's. | 0:01:55 | 0:01:59 | |

Indeed, its popular name is tree shrew, | 0:01:59 | 0:02:01 | |

but its large brain and those grasping hands | 0:02:01 | 0:02:04 | |

have suggested to some that it's related to monkeys. | 0:02:04 | 0:02:07 | |

It seems in fact to contain hints of many different mammals. | 0:02:07 | 0:02:12 | |

One thing, though, is clear. | 0:02:12 | 0:02:14 | |

It's very like the earliest of mammals, | 0:02:14 | 0:02:17 | |

that were living when the dinosaurs dominated the Earth 100 million years ago. | 0:02:17 | 0:02:22 | |

The basic pattern on which there's been such a multitude of variations. | 0:02:22 | 0:02:27 | |

Some of those variations are so extreme that it's difficult to believe | 0:02:27 | 0:02:31 | |

there's any connection between them and the basic theme, | 0:02:31 | 0:02:35 | |

were it not for the evidence of fossils and the anatomy of the living animals. | 0:02:35 | 0:02:40 | |

The tree shrew's continuous activity and swift reactions are typical of a mammal. | 0:02:43 | 0:02:47 | |

A consequence of its ability to generate heat within its body | 0:02:47 | 0:02:51 | |

so that its chemistry works fast and provides it with abundant energy. | 0:02:51 | 0:02:56 | |

This talent probably developed a very long time ago indeed, | 0:02:56 | 0:03:00 | |

at a time when the dinosaurs dominated the Earth. | 0:03:00 | 0:03:02 | |

For fossils of a creature remarkably similar to the living tree shrew | 0:03:02 | 0:03:06 | |

have been found in rocks that are 200 million years old. | 0:03:06 | 0:03:11 | |

Its numerous spiky teeth suggest that it ate insects, | 0:03:13 | 0:03:17 | |

and the shape of its limbs that it was a swift runner. | 0:03:17 | 0:03:20 | |

In fact, its lifestyle was not unlike a tree shrew. | 0:03:20 | 0:03:24 | |

And creatures like it survived alongside the dinosaurs throughout their reign, | 0:03:24 | 0:03:28 | |

probably scampering about at night | 0:03:28 | 0:03:31 | |

when the colder-blooded dinosaurs became torpid in the cold. | 0:03:31 | 0:03:35 | |

Then, 65 million years ago, the dinosaurs disappeared. | 0:03:35 | 0:03:40 | |

The forests and swamps of the world were suddenly empty of large creatures. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:46 | |

Primitive birds flapped through the sky, | 0:03:46 | 0:03:49 | |

but on the ground there were few creatures other than insects and other invertebrates | 0:03:49 | 0:03:53 | |

and those small warm-blooded primitive mammals that fed on them. | 0:03:53 | 0:03:58 | |

And here and there, in odd corners of the world, | 0:03:58 | 0:04:00 | |

their descendants still survive, little changed. | 0:04:00 | 0:04:03 | |

The tree shrew of Malaysia is one. | 0:04:03 | 0:04:05 | |

Here in the streams of the Pyrenees lives another little-known and very engaging one. | 0:04:05 | 0:04:12 | |

It's called a desman. | 0:04:17 | 0:04:20 | |

Like most of these primitive mammals, the desman has a stupendous appetite. | 0:04:22 | 0:04:27 | |

It eats two-thirds of its own body weight every day | 0:04:27 | 0:04:30 | |

and seems never to stop the hunt for more. | 0:04:30 | 0:04:33 | |

Its nose does most of the searching. | 0:04:51 | 0:04:54 | |

It scents the faintest changes in the taste of the water with its nostrils, | 0:04:54 | 0:04:59 | |

and feels its way around with all those whiskers. | 0:04:59 | 0:05:02 | |

Its feet are a combination of web and claw, for both swimming and clambering. | 0:05:17 | 0:05:22 | |

Its eyes are tiny, minute beads hidden in its long fur. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:37 | |

When at last it does find something good, it doesn't give up easily. | 0:05:41 | 0:05:46 | |

Its snorkel nose allows it to snatch a breath | 0:06:05 | 0:06:08 | |

with the minimum of interruption in the struggle. | 0:06:08 | 0:06:11 | |

Its hard-fought-for worm will now keep it going for another hour or so. | 0:06:57 | 0:07:03 | |

Another of these primitive survivals lives along the streams of North America. | 0:07:14 | 0:07:19 | |

It's not only an energetic swimmer, but a burrower as well. | 0:07:21 | 0:07:26 | |

It's possible the swimming way of life and the body design to go with it | 0:07:26 | 0:07:30 | |

led to a similar activity not in water, but underground. | 0:07:30 | 0:07:34 | |

What were paddles have become spades. | 0:07:34 | 0:07:37 | |

This is the star-nosed mole. | 0:07:43 | 0:07:46 | |

The odd fleshy flower on its nose is another highly sensitive smelling device. | 0:07:48 | 0:07:54 | |

It may have yet another way of investigating its surroundings. | 0:07:54 | 0:07:58 | |

Many of these little insect-eaters, such as shrews, | 0:07:58 | 0:08:01 | |

make squeaks so high-pitched that we can't hear them, | 0:08:01 | 0:08:04 | |

and the echo they produce helps the animals to find their way around. | 0:08:04 | 0:08:09 | |

Moles, like desmans and shrews, have formidable appetites | 0:08:19 | 0:08:22 | |

and have to eat every few hours. | 0:08:22 | 0:08:25 | |

Their tunnels are not simply passageways, but traps. | 0:08:25 | 0:08:28 | |

Worms and insects burrowing through the soil drop into them, | 0:08:28 | 0:08:32 | |

and the mole collects whatever turns up. | 0:08:32 | 0:08:35 | |

If its appetite is momentarily sated, | 0:08:37 | 0:08:40 | |

then it paralyses a surplus worm with sharp bites and stores it away in a special larder | 0:08:40 | 0:08:46 | |

before setting off again on its never-ending patrols. | 0:08:46 | 0:08:50 | |

Variations on the theme of the small insect-eater | 0:09:03 | 0:09:06 | |

began to appear soon after the dinosaurs vanished. | 0:09:06 | 0:09:09 | |

Creatures developed that specialised in feeding on one kind of insect - ants and termites. | 0:09:09 | 0:09:15 | |

This is another digger, the aardvark, from Africa. | 0:09:15 | 0:09:19 | |

And this is its South American equivalent, the giant anteater. | 0:09:25 | 0:09:29 | |

The essential equipment for a diet of ants and termites, it seems, | 0:09:35 | 0:09:38 | |

is an elongated snout for poking inside the nests | 0:09:38 | 0:09:42 | |

and a long sticky tongue for collecting the insects. | 0:09:42 | 0:09:45 | |

And the giant anteater has the most extreme version of both that exists. | 0:09:45 | 0:09:50 | |

Termites are easily crushed, | 0:09:55 | 0:09:57 | |

so the anteater has no need of teeth and has lost them all. | 0:09:57 | 0:10:00 | |

Termites' nests, however, can be as hard as cement, | 0:10:00 | 0:10:03 | |

and strong claws and muscular legs are needed to tear them open. | 0:10:03 | 0:10:08 | |

The anteater is very fussy about its food. In spite of its name it seldom eats ants. | 0:10:13 | 0:10:19 | |

Termites, like these, are a much more usual meal, | 0:10:19 | 0:10:22 | |

and even then, it prefers some termites to others. | 0:10:22 | 0:10:26 | |

There are a dozen or so species of mammal round the world | 0:10:37 | 0:10:41 | |

that have specialised in living on ants and termites. | 0:10:41 | 0:10:44 | |

As a lifestyle it doesn't seem to require | 0:10:44 | 0:10:47 | |

a particularly quick intelligence or vivacious disposition. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:51 | |

And all these anteaters are relatively slow-moving creatures. | 0:10:51 | 0:10:55 | |

Because of that and their total lack of teeth, | 0:10:55 | 0:10:58 | |

they might seem to be easy meat for a hunter. | 0:10:58 | 0:11:01 | |

But the giant anteater's front legs are so strong that its hug is lethal, | 0:11:01 | 0:11:05 | |

and few creatures interfere with it. | 0:11:05 | 0:11:08 | |

The termite-eating specialist of Africa, the pangolin, | 0:11:13 | 0:11:16 | |

is much smaller and not nearly such a powerful digger. | 0:11:16 | 0:11:20 | |

It's developed a flexible armour of scales | 0:11:20 | 0:11:23 | |

and can curl itself up into a ball so that it's virtually impregnable. | 0:11:23 | 0:11:26 | |

Its muscular tail also acts as a counterbalance | 0:11:26 | 0:11:29 | |

so that the creature can trundle along with most of its weight on its back legs, | 0:11:29 | 0:11:33 | |

and its front legs at the ready for digging into termite mounds, like this one. | 0:11:33 | 0:11:39 | |

It's so confident of its defences that it takes little notice of any other creature around, | 0:11:51 | 0:11:55 | |

unless they molest it. | 0:11:55 | 0:11:57 | |

Smallest of all, the pygmy silky-furred anteater of South America. | 0:11:59 | 0:12:05 | |

It does seem to be defenceless and can't move fast enough | 0:12:05 | 0:12:08 | |

to escape even the clumsiest hunter. | 0:12:08 | 0:12:11 | |

But it keeps out of the way up in the branches, living almost entirely on tree ants. | 0:12:11 | 0:12:17 | |

This one has a baby on its back, and it may be either male or female, | 0:12:17 | 0:12:21 | |

for both parents take a share in carrying the load. | 0:12:21 | 0:12:25 | |

There's yet another kind of specialist anteater in South America, | 0:13:06 | 0:13:10 | |

intermediate between the giant and the pygmy - the tamandua. | 0:13:10 | 0:13:15 | |

It feeds mostly at night. | 0:13:26 | 0:13:28 | |

Its thick, bristly fur is supposed to protect the tamandua | 0:13:28 | 0:13:32 | |

from the bites of infuriated ants, swarming from their shattered nest. | 0:13:32 | 0:13:37 | |

But when you watch the animal feeding, | 0:13:37 | 0:13:39 | |

you can't help wondering just how effective that protection really is. | 0:13:39 | 0:13:44 | |

Ants and termites are among the most numerous insects, particularly in the tropics. | 0:13:44 | 0:13:49 | |

And the tamandua and its relatives around the world | 0:13:49 | 0:13:51 | |

have little difficulty in finding more than enough to eat. | 0:13:51 | 0:13:56 | |

And there are insects not only in water and in the soil and all over plants, | 0:13:56 | 0:14:02 | |

but in the air, and particularly at night. | 0:14:02 | 0:14:05 | |

It's difficult to realise just how many there are | 0:14:05 | 0:14:08 | |

until you put up a mercury vapour lamp in the tropics. | 0:14:08 | 0:14:11 | |

Here, within a few minutes, you've got all sorts of creatures. | 0:14:11 | 0:14:15 | |

Small moths, crickets, huge beetles, mantises, | 0:14:15 | 0:14:19 | |

big moths, insects of all kinds. | 0:14:19 | 0:14:23 | |

The insects first took to the air about 300 million years ago. | 0:14:24 | 0:14:29 | |

They had it to themselves for about 100 million years, | 0:14:29 | 0:14:33 | |

at least until the arrival of the reptiles. | 0:14:33 | 0:14:35 | |

Whether there were any night-flying, insect-hunting reptiles, we don't know, | 0:14:35 | 0:14:40 | |

but it seems unlikely because reptiles, being cold-blooded, | 0:14:40 | 0:14:44 | |

are usually active during the day. | 0:14:44 | 0:14:46 | |

And then about 150 million years ago, the birds developed. | 0:14:46 | 0:14:50 | |

But there's no reason to suppose | 0:14:50 | 0:14:53 | |

there were any more night-flying birds in the past | 0:14:53 | 0:14:56 | |

than there are today, and that's precious few. | 0:14:56 | 0:14:59 | |

So this great feast of insects | 0:14:59 | 0:15:02 | |

awaited any creature that could master the tricky technique of flying at night. | 0:15:02 | 0:15:08 | |

And one group of the mammals did. | 0:15:08 | 0:15:11 | |

The bats. | 0:15:11 | 0:15:13 | |

The majority of them are hunters of flying insects, | 0:15:38 | 0:15:41 | |

such as moths, mosquitoes or even beetles. | 0:15:41 | 0:15:44 | |

Caught on the wing and eaten at the roost as the bats hang upside down. | 0:15:44 | 0:15:49 | |

Bats began to fly a very long time ago. | 0:16:04 | 0:16:09 | |

These fossil bones of what is undoubtedly a bat are about 50 million years old. | 0:16:09 | 0:16:14 | |

The bat skeleton is very similar to the tree shrew's. | 0:16:14 | 0:16:18 | |

Seen here from above, and now side on. | 0:16:18 | 0:16:22 | |

But how did this flying variation arise? | 0:16:22 | 0:16:26 | |

It may be that the early insect-eaters sought their food up in the branches of trees, | 0:16:26 | 0:16:31 | |

as indeed some kinds of tree shrews do today. | 0:16:31 | 0:16:34 | |

And as they leapt about trying to snatch flying insects from the air, | 0:16:34 | 0:16:39 | |

some may have developed flaps of skin between their arms and the sides of their body | 0:16:39 | 0:16:44 | |

so that they could glide, as the living flying squirrels can today. | 0:16:44 | 0:16:48 | |

They then supported those flaps with their fingers and strengthened the arm muscles | 0:16:48 | 0:16:53 | |

until, eventually, they were able to flap their newly developed wings | 0:16:53 | 0:16:57 | |

and fly in search of their insect prey, and so became bats. | 0:16:57 | 0:17:02 | |

But living on insects has one great disadvantage. | 0:17:04 | 0:17:08 | |

In many parts of the world insects disappear almost totally during the winter. | 0:17:13 | 0:17:18 | |

What does an insect-eater do then? | 0:17:18 | 0:17:21 | |

It hibernates in any sheltered place it can find | 0:17:21 | 0:17:24 | |

where the temperature might remain a few degrees higher than elsewhere, | 0:17:24 | 0:17:28 | |

as it is inside this old Canadian mine. | 0:17:28 | 0:17:32 | |

These tiny lumps, as cold as stone, are living bats. | 0:17:43 | 0:17:47 | |

They fed voraciously during the summer, building up reserves of fat, | 0:17:47 | 0:17:51 | |

but now a profound change has taken place in their bodies. | 0:17:51 | 0:17:55 | |

Their heat has seeped away, and their body processes have slowed down | 0:17:55 | 0:17:59 | |

to almost, but not quite, a complete halt. | 0:17:59 | 0:18:02 | |

They must keep their body chemistry ticking over | 0:18:02 | 0:18:05 | |

just enough to generate sufficient heat to prevent them from freezing solid, | 0:18:05 | 0:18:10 | |

for that they can't survive. | 0:18:10 | 0:18:13 | |

Not all of them are successful. | 0:18:14 | 0:18:16 | |

Sometimes an individual cannot stave off the chill, | 0:18:16 | 0:18:19 | |

falls and is entombed in the ice. | 0:18:19 | 0:18:23 | |

You might think they huddle together to keep warm. | 0:18:30 | 0:18:33 | |

But careful measurements have shown those in groups get just as cold | 0:18:33 | 0:18:37 | |

as those hanging by themselves. | 0:18:37 | 0:18:39 | |

It may be that grouping protects them from another hazard, | 0:18:39 | 0:18:43 | |

the loss of moisture during breathing. | 0:18:43 | 0:18:44 | |

That does seem to be less for those in clusters. | 0:18:44 | 0:18:48 | |

Other creatures also take refuge in the mine, | 0:18:49 | 0:18:52 | |

the very ones which in summer are food for the bats: moths. | 0:18:52 | 0:18:56 | |

Both hunters and hunted shelter together from that overwhelming killer, cold. | 0:18:56 | 0:19:03 | |

In other parts of the world, as here in New Mexico, | 0:19:05 | 0:19:08 | |

bats solve the problem of lack of insect food by migrating. | 0:19:08 | 0:19:13 | |

From this cave they will fly south some 1,000km for the winter. | 0:19:13 | 0:19:18 | |

They have to, to find enough food, | 0:19:18 | 0:19:20 | |

for their populations are measured in millions, | 0:19:20 | 0:19:23 | |

and tonnes of insects are needed. | 0:19:23 | 0:19:26 | |

Caves like these contain the densest populations of mammals | 0:19:44 | 0:19:48 | |

to be found anywhere on Earth. | 0:19:48 | 0:19:51 | |

How is it that all those bats flying at such a speed | 0:19:53 | 0:19:57 | |

can find their way around in the dark? | 0:19:57 | 0:19:59 | |

The answer is echolocation. | 0:19:59 | 0:20:02 | |

Although I can only hear just the faintest twitter, | 0:20:02 | 0:20:06 | |

in fact, each bat is emitting a more or less continuous stream | 0:20:06 | 0:20:11 | |

of high-frequency sound beyond the range of my ears. | 0:20:11 | 0:20:15 | |

But I can translate those into sounds that I can hear using a machine like this. | 0:20:15 | 0:20:19 | |

A bat detector. Listen. | 0:20:19 | 0:20:23 | |

TWITTERING | 0:20:23 | 0:20:28 | |

The system is based on those high-pitched ultrasounds, | 0:20:39 | 0:20:43 | |

like those produced today by shrews | 0:20:43 | 0:20:45 | |

and which the early insect-eaters may have used as well. | 0:20:45 | 0:20:49 | |

The bats have developed that ability | 0:20:49 | 0:20:51 | |

into a highly sophisticated technique called sonar. | 0:20:51 | 0:20:54 | |

Every bat sends out a stream of short squeaks, | 0:20:54 | 0:20:58 | |

which can be as many as 20 or 30 a second, or even more. | 0:20:58 | 0:21:02 | |

From the echoes it can gauge its distance from an object, | 0:21:02 | 0:21:05 | |

whether it's a cave wall or an insect in the air. | 0:21:05 | 0:21:09 | |

The horseshoe bat produces such ultrasounds from its nostrils, | 0:21:10 | 0:21:15 | |

and that construction around the nose serves as a megaphone, | 0:21:15 | 0:21:18 | |

focusing the sound into a beam. | 0:21:18 | 0:21:21 | |

The easiest way to study these signals is to pick them up with a special microphone | 0:21:22 | 0:21:26 | |

and relay them to an oscilloscope so that they can be analysed in a visual form. | 0:21:26 | 0:21:31 | |

The oscilloscope tells us that the bat is producing sounds, | 0:21:35 | 0:21:39 | |

though they are beyond the range of our hearing. | 0:21:39 | 0:21:42 | |

But with the right equipment we can translate those ultrasounds | 0:21:45 | 0:21:49 | |

into sounds that we can hear. | 0:21:49 | 0:21:51 | |

HIGH-PITCHED PULSE | 0:21:51 | 0:21:55 | |

With the oscilloscope as well, we can both see and hear | 0:21:59 | 0:22:02 | |

the variations that the bat can make. | 0:22:02 | 0:22:06 | |

FASTER HIGH-PITCHED PULSE | 0:22:07 | 0:22:09 | |

SLOWER PULSE | 0:22:12 | 0:22:14 | |

FASTER PULSE | 0:22:14 | 0:22:16 | |

Another way to analyse the bat's signals | 0:22:19 | 0:22:22 | |

is to slow them down using a special tape recorder. | 0:22:22 | 0:22:25 | |

These are the horseshoe bat's ultrasounds slowed down 32 times. | 0:22:25 | 0:22:31 | |

LONG WHISTLING NOTES | 0:22:33 | 0:22:35 | |

This is a different species also slowed down. | 0:22:37 | 0:22:40 | |

And it's emitting the ultrasounds through its mouth. | 0:22:40 | 0:22:43 | |

With these echolocating signals bouncing back off the prey, | 0:22:43 | 0:22:48 | |

bats can home in very accurately, raising the rate of output as they approach. | 0:22:48 | 0:22:53 | |

BAT CHIRRUPS | 0:22:53 | 0:22:56 | |

Both sound and action are slowed down 16 times. | 0:22:58 | 0:23:02 | |

The bait, a mealworm, is located precisely by sonar, | 0:23:05 | 0:23:08 | |

and the bat, a pipistrelle, catches it first with its wing membrane, | 0:23:08 | 0:23:14 | |

then flicks it across to its tail membrane, | 0:23:14 | 0:23:18 | |

which is then brought up to its head so the mealworm is passed to the mouth. | 0:23:18 | 0:23:23 | |

The tail membrane is still over the head. | 0:23:23 | 0:23:26 | |

Now it's pulled back, and the bat continues to eat its prey in flight. | 0:23:28 | 0:23:33 | |

Since bats evolved to take advantage of the rich insect larder, | 0:23:34 | 0:23:38 | |

the insects themselves have developed their own countermeasures. Watch. | 0:23:38 | 0:23:42 | |

The lacewing's escape technique | 0:23:48 | 0:23:50 | |

is to close its wings and fall out of the path of the bat. | 0:23:50 | 0:23:54 | |

Lacewings have tiny ears on their wings. | 0:24:12 | 0:24:15 | |

So in this conflict between predator and prey, the insect has tuned in | 0:24:15 | 0:24:20 | |

to be able to hear the bat coming, and therefore take avoiding action. | 0:24:20 | 0:24:25 | |

Some moths, including tiger moths, have an even more elaborate defence. | 0:24:29 | 0:24:33 | |

Not only can they hear bats coming and then dive or spiral away, | 0:24:33 | 0:24:38 | |

but, as a last resort, they can emit their own sounds. | 0:24:38 | 0:24:42 | |

First we will see and hear the sound of the threatening bat, | 0:24:42 | 0:24:47 | |

and then the reaction of the moth. | 0:24:47 | 0:24:50 | |

CRACKLING | 0:24:50 | 0:24:54 | |

The moth has either jammed the bat's signals | 0:24:54 | 0:24:57 | |

or sent some kind of warning which puts the bat off. | 0:24:57 | 0:25:00 | |

Anyway, the moth nearly always escapes. | 0:25:00 | 0:25:04 | |

We may assume the battle of techniques will continue to evolve | 0:25:09 | 0:25:13 | |

as bats further develop their sonar equipment. | 0:25:13 | 0:25:16 | |

The apparatus often dominates the faces of bats. | 0:25:16 | 0:25:20 | |

Huge ears for detecting the echoes, | 0:25:20 | 0:25:22 | |

and on the nose, leaves, flanges and spears for directing the sound, | 0:25:22 | 0:25:27 | |

so they look as grotesque as any gargoyle produced by the medieval imagination. | 0:25:27 | 0:25:33 | |

Some bats tackle insects much bigger than mosquitoes or lacewings. | 0:25:41 | 0:25:44 | |

This one is quite prepared to alight on the forest floor | 0:25:44 | 0:25:48 | |

and grapple with a giant cockroach. | 0:25:48 | 0:25:50 | |

The insect-eating teeth, inherited from the shrew-like ancestor, | 0:26:00 | 0:26:04 | |

are essential here to break up the tough chitin of the insect's body. | 0:26:04 | 0:26:09 | |

When it hangs up, the wings form a kind of tent, | 0:26:33 | 0:26:37 | |

preventing bits of the prey from dropping out. This is a top view. | 0:26:37 | 0:26:42 | |

And an even tougher adversary for the pallid bat, a scorpion. | 0:26:47 | 0:26:52 | |

The poisonous sting is to be carefully avoided. | 0:26:52 | 0:26:56 | |

And some bats are real carnivores. | 0:27:02 | 0:27:06 | |

This huge silk cotton tree contains a small colony of them. | 0:27:11 | 0:27:16 | |

They are hanging at the very top of the hollow interior, | 0:27:21 | 0:27:24 | |

sharing the tree with other species of bats. | 0:27:24 | 0:27:27 | |

This is strange, because this carnivorous species feeds on other bats, | 0:27:28 | 0:27:33 | |

but here it leaves its neighbours in peace. | 0:27:33 | 0:27:36 | |

The also feed on birds, which they catch on their roosts at night. | 0:27:42 | 0:27:47 | |

This is Vampyrum spectrum, but it doesn't actually suck blood. | 0:27:49 | 0:27:53 | |

This is not the true vampire. | 0:27:53 | 0:27:56 | |

This is. Its teeth and mouth | 0:27:56 | 0:27:58 | |

are very specialised for feeding on blood. | 0:27:58 | 0:28:01 | |

Vampires may have originally fed on insects that cluster around grazing animals | 0:28:02 | 0:28:07 | |

and chased them on or near the ground. | 0:28:07 | 0:28:10 | |

By shaving away the skin with razor teeth | 0:28:16 | 0:28:19 | |

and having a saliva that prevents oozing blood clotting, | 0:28:19 | 0:28:22 | |

the vampire shows how extremely specialised a mammal can become. | 0:28:22 | 0:28:27 | |

And it probably all started with insects. | 0:28:27 | 0:28:30 | |

And the originally insect-eating bat | 0:28:33 | 0:28:35 | |

evolved in yet another direction in Arizona and Mexico. | 0:28:35 | 0:28:40 | |

This is the land of big plants, like cactus, yuccas and agaves. | 0:28:41 | 0:28:46 | |

The agave flowers, branching from a mast some six metres high, | 0:28:46 | 0:28:50 | |

attract hummingbirds that feed on the nectar. | 0:28:50 | 0:28:53 | |

And insects, too. | 0:28:55 | 0:28:58 | |

It was probably these that attracted bats in the first place. | 0:28:58 | 0:29:01 | |

Nectar feeding came later. | 0:29:01 | 0:29:03 | |

The bats, in small parties, move from plant to plant, | 0:29:17 | 0:29:21 | |

dipping and sipping at the energy-rich nectar. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:26 | |

Often they get covered in pollen. | 0:29:26 | 0:29:28 | |

In this way they ferry it from plant to plant, so bringing about cross-fertilisation. | 0:29:28 | 0:29:33 | |

So both bat and plant have evolved together to become unlikely partners. | 0:29:33 | 0:29:38 | |

As in other bats, this feeding specialisation involves adaptation. | 0:29:38 | 0:29:43 | |

Long noses and long tongues enable them to reach deep into the flowers. | 0:29:43 | 0:29:48 | |

When flying, seen here in slow motion, | 0:29:59 | 0:30:01 | |

they emit a weak sonar, so they've been called whispering bats. | 0:30:01 | 0:30:07 | |

FAST IRREGULAR PULSE | 0:30:07 | 0:30:10 | |

Carrying pollen and dripping nectar, | 0:30:25 | 0:30:28 | |

this bat will fly on to another agave, where cross-fertilisation will occur. | 0:30:28 | 0:30:32 | |

When the bat has helped that to happen, the fruit will appear. | 0:30:41 | 0:30:45 | |

And fruit, too, has become a food for bats. | 0:30:45 | 0:30:49 | |

This one, lapping at a banana with its tongue, | 0:30:49 | 0:30:52 | |

was the same kind as the one biting into a cockroach with its teeth. | 0:30:52 | 0:30:56 | |

For some bats have developed broad tastes. | 0:30:56 | 0:31:00 | |

Some, however, are exclusively fruit-eaters, | 0:31:05 | 0:31:08 | |

and they include the biggest of all. | 0:31:08 | 0:31:10 | |

These hardly ever live in caves, | 0:31:10 | 0:31:12 | |

but instead hang themselves up in great roosts in trees, called camps. | 0:31:12 | 0:31:17 | |

Their wings are immense, up to two metres across. | 0:31:25 | 0:31:29 | |

Just as birds have to groom their feathers with great care to keep themselves airworthy, | 0:31:29 | 0:31:34 | |

so bats spend a lot of time meticulously cleaning the elastic membrane of skin | 0:31:34 | 0:31:40 | |

on which they depend. | 0:31:40 | 0:31:42 | |

Fruit bats are often called flying foxes, and indeed their faces do look rather foxy. | 0:31:54 | 0:32:00 | |

The fact that they have large eyes | 0:32:00 | 0:32:02 | |

and no immense ears or grotesque ornaments on their noses is significant. | 0:32:02 | 0:32:07 | |

They have no sonar and rely instead on vision to find their way around. | 0:32:07 | 0:32:12 | |

In fact they are so different from insect-eating bats | 0:32:12 | 0:32:15 | |

that they may well be descended from a different branch of the primitive mammals. | 0:32:15 | 0:32:20 | |

They're powerful flyers and regularly go off on journeys of 50km | 0:32:32 | 0:32:37 | |

just to find a tree in fruit. | 0:32:37 | 0:32:39 | |

These are in slow motion. | 0:32:39 | 0:32:42 | |

The structure of a bat's wing is very different from that of a bird's. | 0:33:23 | 0:33:27 | |

The bird's, in effect, is formed from just one finger fringed with feathers. | 0:33:27 | 0:33:32 | |

All the other fingers have been effectively lost. | 0:33:32 | 0:33:36 | |

But the bat's ancestors didn't have feathers with long stiff quills. | 0:33:36 | 0:33:40 | |

They created a broad wing by a different method. | 0:33:40 | 0:33:43 | |

By retaining all their fingers and greatly elongating them | 0:33:43 | 0:33:47 | |

to support the wing membrane. | 0:33:47 | 0:33:49 | |

Their feet also help, for the membrane goes right down to the ankle. | 0:33:49 | 0:33:55 | |

Only the thumb remains free, | 0:33:55 | 0:33:57 | |

and that the bat needs for its toilet | 0:33:57 | 0:34:00 | |

and to hook onto branches as it clambers about. | 0:34:00 | 0:34:03 | |

When, over 50 million years ago, the first mammals flew, | 0:34:08 | 0:34:12 | |

they opened up great possibilities for their descendants. | 0:34:12 | 0:34:16 | |

They had the night sky virtually to themselves, | 0:34:16 | 0:34:18 | |

and they developed into a multitude of different forms to take full advantage of it. | 0:34:18 | 0:34:24 | |

Today there are nearly 1,000 different species of them, | 0:34:24 | 0:34:27 | |

flying through the skies of the world. | 0:34:27 | 0:34:30 | |

Many of them have remained insect-feeders, like their earth-bound ancestors, | 0:34:30 | 0:34:36 | |

but fruit, nectar, blood, birds and even other bats | 0:34:36 | 0:34:41 | |

is by no means the complete list of the diets they've discovered for themselves. | 0:34:41 | 0:34:46 | |

And one of them has actually become a fisherman. | 0:34:46 | 0:34:49 | |

It lives in Central America. | 0:34:51 | 0:34:54 | |

Its closest relatives are all insect-feeders, and it too will take a beetle, like this one, | 0:34:54 | 0:35:00 | |

though in a unique way. | 0:35:00 | 0:35:03 | |

It caught that beetle by using its hind legs as grapnels, | 0:35:04 | 0:35:09 | |

and it goes after fish in the same way. Watch. | 0:35:09 | 0:35:13 | |

It hooked the fish, but not well enough. | 0:35:17 | 0:35:21 | |

So back it comes. | 0:35:28 | 0:35:31 | |

Like other bats, it immediately transfers its capture into its mouth. | 0:35:39 | 0:35:44 | |

And only eats it when it gets back to its roost, stuffing some of it into cheek pouches. | 0:35:46 | 0:35:52 | |

The membrane doesn't go down to the ankle, like most bats', so it's kept clear of the water. | 0:35:58 | 0:36:03 | |

And the claws are as sharp as needles. | 0:36:03 | 0:36:06 | |

But how does it know where to trawl? The answer's ultrasounds again. | 0:36:06 | 0:36:11 | |

BAT CHIRRUPS | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

It's able to detect the ripple of a fish at the surface | 0:36:20 | 0:36:23 | |

and home in on it with deadly accuracy. | 0:36:23 | 0:36:26 | |

But fishing, for the bats, is a rare and very recently acquired talent. | 0:36:42 | 0:36:48 | |

The first really accomplished fisherman amongst the mammals | 0:36:48 | 0:36:51 | |

appeared early on in the history of the group. | 0:36:51 | 0:36:54 | |

When the great ocean-going reptiles, the ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, | 0:36:54 | 0:36:58 | |

disappeared at the end of the age of the dinosaurs, | 0:36:58 | 0:37:01 | |

the mammals were very quick indeed | 0:37:01 | 0:37:03 | |

to fill the space that was left in the economy of the sea. | 0:37:03 | 0:37:08 | |

At first, doubtless, the creature lived partly in the water, partly on land, | 0:37:08 | 0:37:13 | |

rather as the hippopotamus does today, | 0:37:13 | 0:37:15 | |

but very soon, within a few million years, | 0:37:15 | 0:37:19 | |

truly specialised mammalian swimmers appeared. | 0:37:19 | 0:37:22 | |

Some of them grew to be bigger even than the biggest of the dinosaurs - the whales. | 0:37:22 | 0:37:27 | |

And here in the blue waters of the Pacific, off the Hawaiian islands, | 0:37:27 | 0:37:32 | |

every year humpback whales assemble to give birth and to court. | 0:37:32 | 0:37:38 | |

And if you have a lot of patience and even more luck, you may be able to swim among them. | 0:37:38 | 0:37:43 | |

I was lucky enough to dive with a group of whale experts | 0:37:59 | 0:38:02 | |

who knew just how to get close to these magnificent creatures. | 0:38:02 | 0:38:07 | |

And there, in the distance, a 40-tonne mother and her baby. | 0:38:21 | 0:38:27 | |

The changes that have taken place during the descent of these vast creatures | 0:38:31 | 0:38:36 | |

from their little furry ancestors are obviously immense. | 0:38:36 | 0:38:40 | |

But they're all adaptations to a sea-going life. | 0:38:40 | 0:38:43 | |

The forelegs have become flippers and the back legs lost. | 0:38:43 | 0:38:46 | |

But what about their huge increase in size? | 0:38:46 | 0:38:50 | |

The larger you are, the lower the ratio between your volume and your surface area, | 0:38:50 | 0:38:54 | |

and the easier it is to retain heat. | 0:38:54 | 0:38:57 | |

Dinosaurs also had problems about getting chilled | 0:38:57 | 0:39:00 | |

and solved it in a similar way by getting big. | 0:39:00 | 0:39:04 | |

Their size, however, was limited by the strength of bone. | 0:39:04 | 0:39:07 | |

Above a certain weight, leg bones would simply break. | 0:39:07 | 0:39:10 | |

But whales are less hampered. | 0:39:10 | 0:39:12 | |

Their bodies are not supported by legs, but by the water. | 0:39:12 | 0:39:16 | |

So they have grown into the biggest animals the world has seen, | 0:39:16 | 0:39:20 | |

some of them four times bigger than the largest known dinosaur. | 0:39:20 | 0:39:24 | |

As far as we can tell, the whales, when in Hawaiian waters, don't feed at all. | 0:40:28 | 0:40:33 | |

They come here only to court and to give birth to their young. | 0:40:33 | 0:40:37 | |

Around April they begin to swim north, up to the Arctic. | 0:40:41 | 0:40:46 | |

Many of them assemble off the coast of Alaska, | 0:40:48 | 0:40:51 | |

and here they begin to feed. | 0:40:51 | 0:40:54 | |

As they gather on their feeding grounds in ever-increasing numbers, | 0:41:05 | 0:41:09 | |

they begin to behave in a most dramatic way. | 0:41:09 | 0:41:11 | |

The breaching, 40 tonnes of animal right out of the water, | 0:41:16 | 0:41:21 | |

may be something to do with the establishment of territories. | 0:41:21 | 0:41:25 | |

The need to breathe air, bequeathed to them by their mammalian ancestors, | 0:41:46 | 0:41:52 | |

might seem to be a major handicap. | 0:41:52 | 0:41:54 | |

But the whales have minimised the problem by breathing particularly efficiently. | 0:41:54 | 0:41:59 | |

Human beings only clear about 15% of the air in their lungs with a normal breath. | 0:41:59 | 0:42:04 | |

The whale, in great exhalations, gets rid of about 90% of its spent air. | 0:42:04 | 0:42:11 | |

It also has a well-developed system for storing oxygen in the muscles, | 0:42:29 | 0:42:33 | |

and some can swim for up to 40 minutes without drawing breath if they want to. | 0:42:33 | 0:42:40 | |

Humpbacks are one of the group of whales | 0:42:48 | 0:42:50 | |

that feed on shoals of shrimp-like creatures, krill. | 0:42:50 | 0:42:54 | |

Sometimes they concentrate the krill with a ring of bubbles from the blowhole, | 0:42:54 | 0:42:58 | |

and the mouthful is filtered through plates of whalebone hanging from the upper jaw. | 0:42:58 | 0:43:04 | |

In a way they parallel the anteaters. | 0:43:04 | 0:43:06 | |

Both creatures have modified their jaws and lost their teeth | 0:43:06 | 0:43:10 | |

in order to collect swarms of tiny invertebrates. | 0:43:10 | 0:43:14 | |

Another group of whales tackle much bigger prey. | 0:43:16 | 0:43:19 | |

These whales have kept their teeth | 0:43:19 | 0:43:21 | |

and become among the fiercest creatures in the sea. | 0:43:21 | 0:43:24 | |

These are killer whales, and they're hunting seals. | 0:43:24 | 0:43:28 | |

That dot is the head of a seal, desperately searching for safety, | 0:43:35 | 0:43:40 | |

but it has no chance. | 0:43:40 | 0:43:42 | |

That most dramatic and elusive creature, the narwhal, is another of the toothed whales. | 0:43:54 | 0:44:00 | |

And one of its teeth has grown enormous. | 0:44:00 | 0:44:04 | |

Only the males have this impressive tusk, | 0:44:08 | 0:44:11 | |

but no-one yet has discovered just what it's for. | 0:44:11 | 0:44:15 | |

The most familiar toothed whales of all are dolphins and porpoises. | 0:44:21 | 0:44:25 | |

They're the friendliest and also the smallest. | 0:44:25 | 0:44:27 | |

They were among the first whales to be kept in tanks. | 0:44:27 | 0:44:31 | |

As a result, we've been able to watch the moment | 0:44:31 | 0:44:34 | |

that must be among the trickiest of a sea mammal's life, the moment of birth. | 0:44:34 | 0:44:38 | |

This is the mother-to-be. Her belly is swollen, and birth is imminent. | 0:44:38 | 0:44:44 | |

The baby's tail is just showing. | 0:44:44 | 0:44:46 | |

Now it's half out. | 0:44:48 | 0:44:50 | |

And there is the puff of red blood, | 0:44:53 | 0:44:55 | |

as the umbilical cord breaks and the youngster swims free. | 0:44:55 | 0:44:58 | |

Here is that remarkable moment again. | 0:44:58 | 0:45:02 | |

The baby can swim immediately, | 0:45:08 | 0:45:10 | |

but the mother helps it to the surface for its first breath of air. | 0:45:10 | 0:45:14 | |

Now it swims alongside her, gliding just as fast as she does, | 0:45:14 | 0:45:18 | |

seemingly without any difficulty. | 0:45:18 | 0:45:21 | |

Soon, as it swims, it will suckle at that other mammalian device, | 0:45:21 | 0:45:25 | |

the nipple on its mother's underside, to take its first meal of milk. | 0:45:25 | 0:45:30 | |

The dolphins' gymnastic skills, their ability to copy from one another | 0:45:46 | 0:45:50 | |

and their apparent eagerness to learn new tricks from their trainers | 0:45:50 | 0:45:54 | |

have made them the most accomplished and popular performers in oceanaria. | 0:45:54 | 0:45:58 | |

But how intelligent are they? | 0:45:58 | 0:46:01 | |

SQUEAKING | 0:46:01 | 0:46:04 | |

Speculations about dolphin intelligence have been stimulated in particular | 0:46:07 | 0:46:11 | |

by these calls. | 0:46:11 | 0:46:13 | |

Some people have even suggested that dolphins have a true language, | 0:46:13 | 0:46:18 | |

and that if only we were clever enough, we would not only be able to understand, | 0:46:18 | 0:46:22 | |

but might be able to speak it and convey quite complex messages to dolphins. | 0:46:22 | 0:46:27 | |

It's true dolphins not only make sounds when they have their heads above water, | 0:46:27 | 0:46:32 | |

but do so almost continuously below water. | 0:46:32 | 0:46:35 | |

And we can listen to them do it with an underwater microphone. | 0:46:35 | 0:46:39 | |

CLICKING | 0:46:41 | 0:46:46 | |

Over 20 different kinds of calls have been identified. | 0:46:46 | 0:46:49 | |

Some serve to keep a school together when they're travelling at top speed, | 0:46:49 | 0:46:53 | |

and they can swim at 20mph, and they go on long migrations. | 0:46:53 | 0:46:57 | |

Some sounds are warning cries, some call signs | 0:46:57 | 0:47:01 | |

that enable one animal to be recognised at a distance by another. | 0:47:01 | 0:47:06 | |

Complex though these calls are, | 0:47:06 | 0:47:08 | |

no-one has yet demonstrated that dolphins ever put calls together | 0:47:08 | 0:47:12 | |

to form the equivalent of a two-word sentence. | 0:47:12 | 0:47:15 | |

That can be regarded as the beginning of a true language. | 0:47:15 | 0:47:19 | |

But those aren't the only sounds they make. | 0:47:22 | 0:47:24 | |

They also use sound for echolocation in rather the same way that bats do. | 0:47:24 | 0:47:30 | |

That's to say they emit a series of very high-pitched clicks and squeaks, | 0:47:30 | 0:47:35 | |

and by sensing the echoes, | 0:47:35 | 0:47:37 | |

they can detect the presence of objects in the water around them. | 0:47:37 | 0:47:41 | |

The frequencies they use are around 200,000 vibrations per second, | 0:47:41 | 0:47:46 | |

which is about the same as that used by bats | 0:47:46 | 0:47:49 | |

and way, way above the range of the human ear. | 0:47:49 | 0:47:52 | |

But by once again using the bat detector, | 0:47:52 | 0:47:55 | |

this time connected to the underwater microphone, | 0:47:55 | 0:47:58 | |

we can translate those clicks into sounds that we can hear. | 0:47:58 | 0:48:03 | |

Normally, of course, the dolphins use their eyesight in conjunction with echolocation, | 0:48:03 | 0:48:09 | |

but just to show how accurate that echolocation can be, | 0:48:09 | 0:48:13 | |

we're going to blindfold the dolphins. | 0:48:13 | 0:48:16 | |

The dolphin has been trained to retrieve this hoop. | 0:48:22 | 0:48:26 | |

What's more, it can find it in the water | 0:48:26 | 0:48:28 | |

and distinguish it from these two shapes blindfold. Watch. | 0:48:28 | 0:48:34 | |

CLICKING | 0:48:42 | 0:48:45 | |

And just to show that that's no fluke, let's try it again. | 0:48:50 | 0:48:55 | |

The waters around Hawaii are also filled with strange sounds, | 0:49:00 | 0:49:04 | |

but these we know far less about. | 0:49:04 | 0:49:07 | |

DEEP GROANS | 0:49:07 | 0:49:11 | |

A moment ago we made this recording with an underwater microphone | 0:49:14 | 0:49:18 | |

here in the Pacific near Hawaii. Just listen to this. | 0:49:18 | 0:49:23 | |

DEEP GROANS | 0:49:23 | 0:49:28 | |

LOW WAIL | 0:49:31 | 0:49:36 | |

This is the sound of a humpback whale | 0:49:43 | 0:49:46 | |

that's lying in the water about 100 feet below us in the sea. | 0:49:46 | 0:49:50 | |

There are many extraordinary things about its song. | 0:49:52 | 0:49:54 | |

To start with, they're so long. | 0:49:54 | 0:49:57 | |

They may last anything from a quarter of an hour to half an hour. | 0:49:57 | 0:50:01 | |

Although the various themes within the song may be repeated a varying number of times, | 0:50:01 | 0:50:07 | |

the actual themes themselves and the order in which they appear in the song is unvarying. | 0:50:07 | 0:50:12 | |

And even more remarkable, all the singing whales within this area | 0:50:13 | 0:50:17 | |

sing the same song. | 0:50:17 | 0:50:20 | |

WHALES SING | 0:50:20 | 0:50:24 | |

After the breeding season they disperse. Next year they'll be back, | 0:50:24 | 0:50:28 | |

but next year they'll have a slightly different song | 0:50:28 | 0:50:31 | |

which contains themes that have never been heard before. | 0:50:31 | 0:50:35 | |

And all of them will be singing the same song. | 0:50:35 | 0:50:38 | |

And that song can be heard echoing throughout these waters | 0:50:39 | 0:50:43 | |

for miles and miles and miles. | 0:50:43 | 0:50:47 | |

WHALES SINGING | 0:50:48 | 0:50:52 | |

It seems extraordinary that a creature like this | 0:50:52 | 0:50:55 | |

could have given rise to whales, as well as to moles and bats and anteaters. | 0:50:55 | 0:51:01 | |

Those swimming, burrowing, flying specialists | 0:51:01 | 0:51:03 | |

appeared a few million years after the dinosaurs disappeared. | 0:51:03 | 0:51:07 | |

The only mammals around from which they could have sprung | 0:51:07 | 0:51:10 | |

were these small furry insect-eaters. | 0:51:10 | 0:51:14 | |

So this tiny theme has proved to be one of the most fruitful in the animal kingdom. | 0:51:14 | 0:51:19 | |

There are still some variations we haven't looked at yet - | 0:51:19 | 0:51:23 | |

the vegetarians, the leaf-and-grass-eaters, | 0:51:23 | 0:51:25 | |

and the carnivores that developed to prey on them. | 0:51:25 | 0:51:28 | |

They will have to have a programme of their own. | 0:51:28 | 0:51:31 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:51:55 | 0:51:59 |