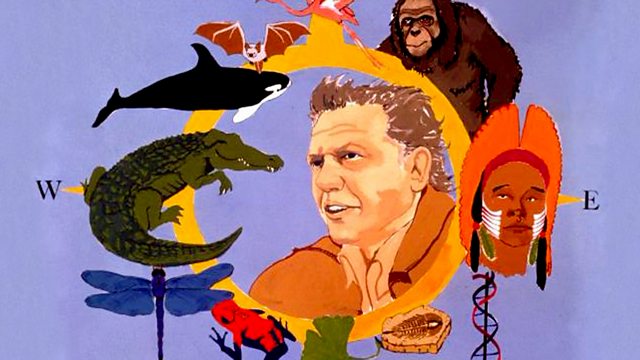

The Hunters and the Hunted Life on Earth

Similar Content

Browse content similar to The Hunters and the Hunted. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

The forests of the world, whether the jungles of Asia | 0:00:53 | 0:00:56 | |

or the tropical rainforests of South America or woodlands in Europe, | 0:00:56 | 0:01:01 | |

haven't really changed in their essentials for 50 million years. | 0:01:01 | 0:01:06 | |

Then, as now, there were ferns and flowering plants | 0:01:06 | 0:01:11 | |

and tall trees with broad leaves. Leaves, in fact, everywhere, | 0:01:11 | 0:01:14 | |

sprouting and falling season after season, century after century. | 0:01:14 | 0:01:19 | |

Dinosaurs had fed on leaves. | 0:01:19 | 0:01:21 | |

Some of the biggest were plant-eaters. | 0:01:21 | 0:01:24 | |

But when the dinosaurs disappeared, | 0:01:24 | 0:01:26 | |

for reasons we still don't understand, | 0:01:26 | 0:01:28 | |

these forests were left empty of any large creatures. | 0:01:28 | 0:01:31 | |

There were just birds in the trees, | 0:01:31 | 0:01:34 | |

insects and a few small reptiles and amphibians. | 0:01:34 | 0:01:37 | |

And they stayed empty for several hundred thousand years. | 0:01:37 | 0:01:42 | |

That may seem a very long time, | 0:01:42 | 0:01:44 | |

but in geological time it's really quite short. | 0:01:44 | 0:01:47 | |

And then, amongst those small creatures, | 0:01:47 | 0:01:51 | |

there were warm-blooded, | 0:01:51 | 0:01:52 | |

inconspicuous little animals that fed on insects. | 0:01:52 | 0:01:55 | |

They'd been around a long time. | 0:01:55 | 0:01:58 | |

They had been in the forests with the dinosaurs, | 0:01:58 | 0:02:01 | |

but with the dinosaurs gone, | 0:02:01 | 0:02:03 | |

those creatures began to develop | 0:02:03 | 0:02:05 | |

ways of raiding this untapped larder of leaves. | 0:02:05 | 0:02:10 | |

And their descendants are still at it. | 0:02:10 | 0:02:12 | |

One or two have become extraordinarily specialised. | 0:02:30 | 0:02:34 | |

The three-toed sloth in South America | 0:02:34 | 0:02:36 | |

eats only the leaves of the Cecropia tree. | 0:02:36 | 0:02:39 | |

Hanging beneath the branches, no predators can reach it. | 0:02:39 | 0:02:42 | |

And perhaps lulled by this security, it's fallen into a kind of torpor | 0:02:42 | 0:02:47 | |

so that it's totally unable to move any faster than this. | 0:02:47 | 0:02:51 | |

Others became nimble and agile acrobats - the monkeys. | 0:02:52 | 0:02:58 | |

But the leaf-eaters didn't have everything their own way. | 0:02:58 | 0:03:01 | |

There were also hunters in the forest, | 0:03:07 | 0:03:10 | |

moving silently and stalking alone. | 0:03:10 | 0:03:14 | |

These duels are also played out at night. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:45 | |

From the beginnings of the mammals' history they'd been able, | 0:03:47 | 0:03:50 | |

with the help of warm bodies, to remain active | 0:03:50 | 0:03:53 | |

even when the warming sun had gone down. | 0:03:53 | 0:03:56 | |

A great proportion of them have never lost the habit | 0:03:56 | 0:03:58 | |

and venture out only under the cover of darkness | 0:03:58 | 0:04:02 | |

to nibble buds, bark and green shoots. | 0:04:02 | 0:04:05 | |

This is a dormouse. | 0:04:05 | 0:04:07 | |

On the woodland floor, a little hamster busily gathers food. | 0:04:13 | 0:04:17 | |

It needs great quantities, for vegetation contains | 0:04:17 | 0:04:21 | |

little nourishment in proportion to its bulk. | 0:04:21 | 0:04:24 | |

But eating for hours on end out in the open can be dangerous, | 0:04:25 | 0:04:29 | |

so the hamster stuffs all it can find | 0:04:29 | 0:04:31 | |

into its cheek pouches as quickly as possible | 0:04:31 | 0:04:34 | |

and then scampers back to the safety of its burrow. | 0:04:34 | 0:04:38 | |

There it unloads its collection and eats it at leisure. | 0:04:41 | 0:04:44 | |

Throughout the summer, it builds up immense stores down here, | 0:04:44 | 0:04:49 | |

because soon another problem will face it, | 0:04:49 | 0:04:51 | |

as it faces many other vegetarians. | 0:04:51 | 0:04:54 | |

The frozen forests can no longer provide sufficient food | 0:05:06 | 0:05:10 | |

to sustain the army of vegetarians | 0:05:10 | 0:05:12 | |

that gnawed and nibbled here throughout the summer. | 0:05:12 | 0:05:15 | |

The dormouse deals with the problem by hibernating. | 0:05:26 | 0:05:30 | |

Its blood cools to only a few degrees above freezing, | 0:05:30 | 0:05:33 | |

and the motors of its body slow down and idle, | 0:05:33 | 0:05:36 | |

driven only by the fat accumulated during the leafy days of summer. | 0:05:36 | 0:05:41 | |

The wood mouse, too, lives off its fat, though it doesn't hibernate | 0:05:44 | 0:05:49 | |

and manages to keep going by finding seeds and gnawing bark. | 0:05:49 | 0:05:53 | |

This is the time when the old and the weak die, | 0:06:00 | 0:06:03 | |

and only the strongest survive. | 0:06:03 | 0:06:06 | |

Bigger creatures too, like deer, | 0:06:13 | 0:06:15 | |

are driven to search for nuts and to strip bark from trees. | 0:06:15 | 0:06:20 | |

But after months of hardship, | 0:06:21 | 0:06:24 | |

the year eventually turns and the world becomes green again. | 0:06:24 | 0:06:28 | |

Among the leaves that sprouted | 0:06:28 | 0:06:30 | |

during the springs of some 25 million years ago, | 0:06:30 | 0:06:33 | |

there was a sudden increase in a particular kind - grass. | 0:06:33 | 0:06:38 | |

The spread of grass was probably triggered | 0:06:38 | 0:06:41 | |

by a drying of the climate. | 0:06:41 | 0:06:42 | |

It may appear to be a simple kind of plant, little more than leaves, | 0:06:42 | 0:06:47 | |

but it is a complex and specialised one. | 0:06:47 | 0:06:50 | |

It has tiny flowers that rely on the wind for pollination. | 0:06:50 | 0:06:54 | |

Its leaves grow not from the tip, like most other plants, | 0:06:54 | 0:06:57 | |

but from the bottom, close to the ground. | 0:06:57 | 0:07:00 | |

So when a fire sweeps over the plains, the leaves may burn, | 0:07:00 | 0:07:04 | |

but new ones will sprout from the root stocks almost immediately. | 0:07:04 | 0:07:09 | |

Similarly, when animals nibble the top part, | 0:07:09 | 0:07:12 | |

the bottom continues to grow, | 0:07:12 | 0:07:13 | |

providing a never-ending supply of succulent food. | 0:07:13 | 0:07:17 | |

Leaf-eaters from the forest soon moved out onto the plains | 0:07:26 | 0:07:30 | |

to gather this new and bountiful supply of sustenance. | 0:07:30 | 0:07:35 | |

Leaves are not, however, easy to digest. | 0:07:39 | 0:07:42 | |

To extract their nourishment, | 0:07:42 | 0:07:45 | |

they have to be worked on by the digestive juices for a long time. | 0:07:45 | 0:07:48 | |

And rabbits make this happen in a most surprising way. | 0:07:48 | 0:07:52 | |

Having nibbled a stomachful above ground, | 0:07:55 | 0:07:58 | |

the rabbit retreats to its burrow. | 0:07:58 | 0:08:01 | |

Here it excretes special mucus-covered pellets, | 0:08:02 | 0:08:06 | |

but the grass in them is only half-digested. | 0:08:06 | 0:08:09 | |

As each pellet emerges, the rabbit immediately swallows it, | 0:08:09 | 0:08:13 | |

so that eventually all its food | 0:08:13 | 0:08:15 | |

passes through its digestive system twice. | 0:08:15 | 0:08:18 | |

These creatures also live entirely on plants. | 0:08:33 | 0:08:38 | |

They're buffalo, and I'm in North America. | 0:08:38 | 0:08:41 | |

Like all vegetarians, they have teeth | 0:08:41 | 0:08:44 | |

that are specially modified for the job. | 0:08:44 | 0:08:47 | |

Those at the front here are nippers, | 0:08:47 | 0:08:50 | |

which shear off the grass or the browse. | 0:08:50 | 0:08:53 | |

Then, at the back, there are these grinding molars, | 0:08:53 | 0:08:56 | |

a great battery of them. | 0:08:56 | 0:08:58 | |

They're open-rooted, so they keep on growing as the enamel wears down. | 0:08:58 | 0:09:02 | |

They have these ridges, | 0:09:02 | 0:09:04 | |

which help to break down the walls of the cellulose in the plant, | 0:09:04 | 0:09:07 | |

and, also, the jaw can be moved from side to side | 0:09:07 | 0:09:11 | |

to help in the grinding process. | 0:09:11 | 0:09:13 | |

Gathering sufficient grass to sustain an animal this size | 0:09:21 | 0:09:25 | |

takes a long time - up to nine hours a day. | 0:09:25 | 0:09:28 | |

But even that battery of grinding teeth | 0:09:28 | 0:09:30 | |

doesn't solve the problem of digesting grass. | 0:09:30 | 0:09:33 | |

And the buffalo also has to give its meals a double treatment, | 0:09:33 | 0:09:37 | |

though in a rather neater way than that used by the rabbit. | 0:09:37 | 0:09:41 | |

The chewed grass goes down to a large chamber, the stomach, | 0:09:41 | 0:09:45 | |

that serves as a fermentation vat | 0:09:45 | 0:09:47 | |

and contains a particularly rich brew of bacteria | 0:09:47 | 0:09:51 | |

and single-celled creatures. | 0:09:51 | 0:09:53 | |

These actively swimming little organisms are so small | 0:09:53 | 0:09:57 | |

that a thousand million of them could get into a teaspoon. | 0:09:57 | 0:10:00 | |

The rectangular slabs are fragments of leaves. | 0:10:00 | 0:10:03 | |

No mammal can digest the cellulose walls of plant cells, | 0:10:03 | 0:10:08 | |

but these micro-organisms can. | 0:10:08 | 0:10:11 | |

They produce a ferment which dissolves the cellulose, | 0:10:11 | 0:10:14 | |

changing it into a substance that the buffalo can absorb. | 0:10:14 | 0:10:18 | |

But the bodies of the microbes also contain valuable protein. | 0:10:18 | 0:10:22 | |

This, too, will be digested, | 0:10:22 | 0:10:24 | |

but not until the half-digested mash, or cud, | 0:10:24 | 0:10:28 | |

is brought up a lump at a time... | 0:10:28 | 0:10:31 | |

..and given a second chewing. | 0:10:34 | 0:10:37 | |

One mouthful goes down for a second time... | 0:10:42 | 0:10:46 | |

..and up comes another. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:51 | |

Many grass-eaters chew the cud like this, | 0:10:51 | 0:10:53 | |

and a very convenient technique it is, too. | 0:10:53 | 0:10:56 | |

It can be done away from the open pasture, | 0:10:56 | 0:10:58 | |

lying concealed and comfortable in the shade, | 0:10:58 | 0:11:01 | |

or with the head held high if there is a need to keep watch for danger. | 0:11:01 | 0:11:06 | |

So, many leaf-eaters from the forest found food on the plain, | 0:11:12 | 0:11:17 | |

and out of the forest, too, in pursuit of them, came the hunters. | 0:11:17 | 0:11:21 | |

The serval is considerably bigger than a domestic cat. | 0:11:53 | 0:11:57 | |

It hunts rats and mice | 0:11:57 | 0:11:58 | |

and must catch about a dozen each day in order to survive. | 0:11:58 | 0:12:03 | |

Flesh-eaters need quite different teeth from vegetarians. | 0:12:05 | 0:12:08 | |

Instead of grinders and pulpers | 0:12:08 | 0:12:11 | |

they require the armoury of the butcher's shop. | 0:12:11 | 0:12:15 | |

A lion has two pairs of fangs at the front, | 0:12:15 | 0:12:18 | |

daggers to stab the prey and grip it unrelentingly as it struggles. | 0:12:18 | 0:12:23 | |

At the front, nipping teeth to pick off strands of meat. | 0:12:23 | 0:12:28 | |

At the back, the cutters. | 0:12:28 | 0:12:30 | |

Self-sharpening blades which mesh onto one another so accurately | 0:12:30 | 0:12:34 | |

that they can shear through hide, tendons, even bones. | 0:12:34 | 0:12:38 | |

These are why lions and cats chew with the sides of their mouths. | 0:12:38 | 0:12:43 | |

With such weapons around, it's hardly surprising | 0:12:43 | 0:12:46 | |

one of the most pressing concerns of leaf-eaters on the plains | 0:12:46 | 0:12:49 | |

is to keep out of the way. | 0:12:49 | 0:12:52 | |

One of the ways to do that is to go underground. | 0:12:52 | 0:12:56 | |

These are the waste tips of the mole rat, | 0:12:56 | 0:12:58 | |

a creature that has foregone the lush leaves of the grass | 0:12:58 | 0:13:02 | |

and specialised instead on eating the roots. | 0:13:02 | 0:13:05 | |

It tunnels industriously a few inches below the surface, | 0:13:24 | 0:13:28 | |

nipping off the grass roots from beneath. | 0:13:28 | 0:13:32 | |

Eyes are no use underground, and the mole rat has become totally blind, | 0:13:32 | 0:13:36 | |

the furry skin of its head | 0:13:36 | 0:13:38 | |

having completely covered the vestiges of its eyes. | 0:13:38 | 0:13:41 | |

It finds its way around by touch, | 0:13:41 | 0:13:43 | |

using lines of bristles growing on either side of its head. | 0:13:43 | 0:13:47 | |

It happily scuttles along its dark tunnels, | 0:13:47 | 0:13:50 | |

not only forwards, but backwards, like a tram. | 0:13:50 | 0:13:53 | |

For burrowing it uses predominantly its large and powerful gnawing teeth | 0:13:53 | 0:13:57 | |

and its shovel-shaped snout. | 0:13:57 | 0:14:00 | |

It excavates enormously long tunnels beneath the turf | 0:14:02 | 0:14:05 | |

and guards them energetically | 0:14:05 | 0:14:07 | |

to protect its supply of roots and bulbs growing down from the ceiling. | 0:14:07 | 0:14:11 | |

If a mole rat meets a stranger in its tunnel, | 0:14:17 | 0:14:20 | |

there is likely to be trouble. | 0:14:20 | 0:14:22 | |

Having established by smell that they are rivals, | 0:14:34 | 0:14:37 | |

their first reaction is to build a wall between the two territories. | 0:14:37 | 0:14:41 | |

If they still run into one another, then they fight. | 0:14:51 | 0:14:55 | |

In the spring, particularly large mounds appear above their runs, | 0:15:11 | 0:15:16 | |

thrown up by the females as they excavate their breeding chambers. | 0:15:16 | 0:15:20 | |

Each of these underground mansions has larders stocked with bulbs, | 0:15:20 | 0:15:24 | |

special lavatories and passages to the tunnels where the males live. | 0:15:24 | 0:15:28 | |

Here the young, blind like their parents, are born and reared. | 0:15:28 | 0:15:33 | |

Mole rats are the most dedicated of underground dwellers. | 0:15:33 | 0:15:37 | |

Other inhabitants of the plain, like these prairie dogs, | 0:15:37 | 0:15:40 | |

are rather more confident about life. | 0:15:40 | 0:15:43 | |

Prairie dogs are also burrowers, | 0:15:50 | 0:15:53 | |

but they spend much of their time not below ground, but above it. | 0:15:53 | 0:15:56 | |

They actively farm their fields. | 0:16:00 | 0:16:03 | |

If a plant they don't like to eat, such as sage, | 0:16:03 | 0:16:06 | |

takes root on their land, they will cut it down | 0:16:06 | 0:16:08 | |

and so make room for more of the plants that they do like. | 0:16:08 | 0:16:12 | |

If one patch of pasture gets overgrazed, | 0:16:12 | 0:16:14 | |

they abandon it and let it lie fallow | 0:16:14 | 0:16:17 | |

while they feed on another patch. | 0:16:17 | 0:16:19 | |

They live in huge towns many thousands strong. | 0:16:26 | 0:16:30 | |

These great communities are made up of groups of about 30 animals, | 0:16:30 | 0:16:34 | |

which all know one another personally | 0:16:34 | 0:16:36 | |

and often have interconnected burrows. | 0:16:36 | 0:16:39 | |

When these neighbours meet, they kiss and groom one another. | 0:16:39 | 0:16:43 | |

They exchange many kinds of signals. | 0:16:46 | 0:16:49 | |

A citizen declares his ownership of a burrow like this. | 0:16:49 | 0:16:53 | |

SCREECHING | 0:16:53 | 0:16:55 | |

They also bark warnings when they spot danger, | 0:17:05 | 0:17:08 | |

such as eagles or coyotes on the hunt. | 0:17:08 | 0:17:11 | |

BARKING | 0:17:11 | 0:17:13 | |

So, as the open plains spread through the world, | 0:17:15 | 0:17:18 | |

the animals that left the forests to graze there | 0:17:18 | 0:17:20 | |

developed different ways of digesting grass | 0:17:20 | 0:17:23 | |

and of protecting themselves in this dangerously exposed environment. | 0:17:23 | 0:17:28 | |

During this period, South America, where I am now, | 0:17:28 | 0:17:32 | |

became isolated as a gigantic island. | 0:17:32 | 0:17:35 | |

The land bridge of Panama sank beneath the sea. | 0:17:35 | 0:17:39 | |

Cut off from the rest of the world, | 0:17:39 | 0:17:41 | |

the inhabitants of these grasslands, the pampas, | 0:17:41 | 0:17:44 | |

developed into forms that to our eyes seem very extraordinary indeed. | 0:17:44 | 0:17:50 | |

One looked like a cross between a camel and an elephant. | 0:17:51 | 0:17:55 | |

There were huge grazing beasts bigger than rhinos, | 0:17:55 | 0:17:58 | |

and an armoured animal the size of a small car | 0:17:58 | 0:18:01 | |

that trundled about beneath a great dome of bone. | 0:18:01 | 0:18:05 | |

These vegetarians were preyed on | 0:18:05 | 0:18:07 | |

by gigantic flightless birds with beaks like hatchets | 0:18:07 | 0:18:10 | |

and hunters with sabre teeth that looked like tigers | 0:18:10 | 0:18:14 | |

but bore their young in pouches, like kangaroos. | 0:18:14 | 0:18:17 | |

But about five million years ago, | 0:18:17 | 0:18:19 | |

the land link with North America was re-established | 0:18:19 | 0:18:22 | |

and different creatures from the north moved south. | 0:18:22 | 0:18:25 | |

As the populations mixed, | 0:18:25 | 0:18:28 | |

northerners and southerners competed for the same food and territory. | 0:18:28 | 0:18:32 | |

There were winners and losers, | 0:18:32 | 0:18:33 | |

and most of the strange South Americans disappeared. | 0:18:33 | 0:18:37 | |

But in this gigantic cave in Patagonia, | 0:18:37 | 0:18:39 | |

on the southern tip of the continent, | 0:18:39 | 0:18:41 | |

tantalising evidence has been found of a really dramatic survival. | 0:18:41 | 0:18:46 | |

At the end of the 19th century a German came down here | 0:18:46 | 0:18:49 | |

to settle and to ranch cattle and sheep. | 0:18:49 | 0:18:51 | |

And this cave lay on his estancia. | 0:18:51 | 0:18:55 | |

When he came to explore it, he found, at the back, | 0:18:55 | 0:18:59 | |

behind that line of boulders, | 0:18:59 | 0:19:01 | |

a pile of the most extraordinary bones, skin and dung. | 0:19:01 | 0:19:07 | |

He hung a piece of the skin on one of the posts | 0:19:07 | 0:19:10 | |

that marked the boundary of his property. | 0:19:10 | 0:19:12 | |

And there, a few years later, a Swedish traveller noticed it. | 0:19:12 | 0:19:17 | |

He sent it to the Natural History Museum in London, | 0:19:17 | 0:19:21 | |

and there they identified it as belonging to a giant ground sloth. | 0:19:21 | 0:19:27 | |

This animal had been known for some time from its fossilised bones. | 0:19:29 | 0:19:33 | |

But the remains in the cave were not fossilised | 0:19:33 | 0:19:36 | |

and seemed extraordinarily fresh. | 0:19:36 | 0:19:38 | |

Could the animal still be alive somewhere? | 0:19:38 | 0:19:41 | |

Why were there such huge piles of dung in the cave? | 0:19:41 | 0:19:44 | |

Was it possible that the line of boulders | 0:19:44 | 0:19:46 | |

was the remains of a wall built by men | 0:19:46 | 0:19:49 | |

to pen the animals in the cave, like enormous cattle? | 0:19:49 | 0:19:53 | |

For a long time, nobody knew the answers to those questions. | 0:19:53 | 0:19:57 | |

But recent excavations have at least cleared up some of them. | 0:19:57 | 0:20:01 | |

A few years ago, these bits of bone were dug up here. | 0:20:01 | 0:20:04 | |

This is a bit of the jaw, and this of the hip. | 0:20:04 | 0:20:07 | |

From tests on them and their position in the ground, we now know | 0:20:07 | 0:20:11 | |

that the giant ground sloths were here up to about 5,000 years ago. | 0:20:11 | 0:20:17 | |

The same excavations have also shown that the Indians were here | 0:20:17 | 0:20:21 | |

between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago. | 0:20:21 | 0:20:23 | |

So it is indeed possible that the Indians hunted those huge animals. | 0:20:23 | 0:20:29 | |

But that line of boulders, I'm afraid, | 0:20:29 | 0:20:32 | |

is no more than a natural fall of rock from the ceiling. | 0:20:32 | 0:20:35 | |

And the piles of dung behind it are no mystery either. | 0:20:35 | 0:20:38 | |

We now know that many animals habitually use the same dung hills, | 0:20:38 | 0:20:42 | |

and maybe the sloths came in here during the winter to keep warm. | 0:20:42 | 0:20:47 | |

But I'm afraid the animal is really now extinct. | 0:20:47 | 0:20:50 | |

You can't hide a creature twice the size of a cow | 0:20:50 | 0:20:54 | |

in the bleak emptinesses of Patagonia. | 0:20:54 | 0:20:57 | |

So we've missed our chance of seeing it. | 0:20:57 | 0:21:01 | |

But it was quite a close thing, in geological terms, at any rate. | 0:21:01 | 0:21:05 | |

The South American giants may have gone, | 0:21:06 | 0:21:09 | |

but some less conspicuous but equally bizarre creatures remain. | 0:21:09 | 0:21:13 | |

There are many kinds of armadillos, | 0:21:13 | 0:21:15 | |

trotting over the pampas and foraging in the forests, | 0:21:15 | 0:21:18 | |

diminutive descendants of the huge extinct ones. | 0:21:18 | 0:21:22 | |

There are some very odd rodents here, too. | 0:21:24 | 0:21:26 | |

These are capybaras. They find safety in water. | 0:21:26 | 0:21:31 | |

Like a hippopotamus, their eyes, ears and nostrils | 0:21:31 | 0:21:34 | |

are all on the top of the head. | 0:21:34 | 0:21:36 | |

And for the same reason - | 0:21:36 | 0:21:37 | |

so that the capybara can lie in the water | 0:21:37 | 0:21:40 | |

fully aware of what's going on around it, | 0:21:40 | 0:21:43 | |

but with practically all its body hidden beneath the surface. | 0:21:43 | 0:21:47 | |

Capybaras are the largest rodents to be found anywhere in the world. | 0:22:07 | 0:22:11 | |

A male grows to be three feet long, a metre or so, | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

and they're the descendants of an even bigger extinct ancestor. | 0:22:14 | 0:22:19 | |

They move around in large family groups | 0:22:21 | 0:22:23 | |

and are excellent swimmers from an early age, | 0:22:23 | 0:22:26 | |

though sometimes the young find even easier ways of getting around. | 0:22:26 | 0:22:31 | |

They eat virtually nothing except leaves of one sort or another, | 0:22:47 | 0:22:50 | |

either water plants or the grasses of the river bank. | 0:22:50 | 0:22:55 | |

The viscacha is the South American equivalent of the prairie dog, | 0:23:00 | 0:23:04 | |

though it's very much bigger, about the size of a badger. | 0:23:04 | 0:23:08 | |

At dusk it comes up from its sleeping quarters | 0:23:12 | 0:23:15 | |

and surveys the world before starting on its nightly labour | 0:23:15 | 0:23:20 | |

of nibbling grass for hours on end. | 0:23:20 | 0:23:22 | |

The mara, another South American rodent, has very long legs, | 0:23:30 | 0:23:34 | |

for it finds safety not by burrowing underground, but by running. | 0:23:34 | 0:23:38 | |

So when it browses, it's always on the alert, | 0:23:38 | 0:23:41 | |

nervously watching for danger and so highly strung | 0:23:41 | 0:23:44 | |

that it will race away at the crack of a twig | 0:23:44 | 0:23:47 | |

or the faint whiff of a dangerous scent. | 0:23:47 | 0:23:50 | |

This little leaf-eater | 0:23:52 | 0:23:54 | |

appeared some 50 million years ago in North America. | 0:23:54 | 0:23:58 | |

It was no bigger than a spaniel, | 0:23:58 | 0:24:00 | |

and it had four toes on its front legs and three on the back. | 0:24:00 | 0:24:03 | |

Like the mara, it sought safety in speed. | 0:24:03 | 0:24:07 | |

The longer your legs, the longer strides you can take | 0:24:07 | 0:24:10 | |

and the faster you can run. | 0:24:10 | 0:24:12 | |

Over generations these creatures | 0:24:12 | 0:24:14 | |

increased the length of their legs by rising up on their toes. | 0:24:14 | 0:24:18 | |

After millions of years some developed | 0:24:18 | 0:24:20 | |

which carried their main body weight on the middle toe alone, | 0:24:20 | 0:24:24 | |

and the side toes barely touched the ground. | 0:24:24 | 0:24:27 | |

Their continuously growing nail on the middle toe | 0:24:27 | 0:24:30 | |

became thick to reduce wear - a hoof. | 0:24:30 | 0:24:32 | |

Eventually the side toes disappeared altogether. | 0:24:32 | 0:24:36 | |

These were the early horses, | 0:24:36 | 0:24:38 | |

and they spread right across the northern hemisphere | 0:24:38 | 0:24:41 | |

and down into Africa. | 0:24:41 | 0:24:42 | |

Zebras, with their long legs jointed to a stiff backbone, | 0:24:50 | 0:24:54 | |

can gallop at speeds of up to 40 miles, 65km an hour. | 0:24:54 | 0:25:00 | |

They run in groups for the safety in numbers. | 0:25:00 | 0:25:02 | |

It's more difficult to take an animal by surprise | 0:25:02 | 0:25:05 | |

if it's in a group, | 0:25:05 | 0:25:06 | |

and a swirling mass, like this, makes a very confusing target. | 0:25:06 | 0:25:10 | |

Other grass-eaters on the plains | 0:25:10 | 0:25:13 | |

find protection from hunters in different ways. | 0:25:13 | 0:25:17 | |

The rhinoceros has a hide as tough as any mammal's, | 0:25:17 | 0:25:21 | |

proof against the sharpest claws and teeth. | 0:25:21 | 0:25:24 | |

Its sheer bulk makes it very formidable, too. | 0:25:24 | 0:25:27 | |

But that also helps it with the universal problem for browsers - | 0:25:28 | 0:25:32 | |

how to digest cellulose. | 0:25:32 | 0:25:35 | |

The rhinoceros doesn't chew cud. | 0:25:36 | 0:25:39 | |

Instead it keeps its food in its belly for a very long time indeed, | 0:25:39 | 0:25:44 | |

so that the bacteria have plenty of time to work on it. | 0:25:44 | 0:25:47 | |

To do that, you need a very large belly in which to store the food, | 0:25:47 | 0:25:52 | |

and if you are to carry a large belly, you must be big. | 0:25:52 | 0:25:55 | |

Only one creature on the plains is much bigger than the rhino. | 0:25:56 | 0:26:00 | |

The elephant is the largest land animal alive, | 0:26:09 | 0:26:12 | |

and its huge size makes it virtually invulnerable. | 0:26:12 | 0:26:16 | |

No hunter is big enough or powerful enough | 0:26:16 | 0:26:19 | |

to pull down a full-grown elephant. | 0:26:19 | 0:26:22 | |

It's so big, it hardly gets any shade | 0:26:22 | 0:26:25 | |

from any of the trees occasionally studding the plains, | 0:26:25 | 0:26:28 | |

and out in the baking sun it's in danger of getting overheated. | 0:26:28 | 0:26:32 | |

Flapping its ears helps considerably in cooling the blood, | 0:26:32 | 0:26:36 | |

as it passes through the veins of the ears. | 0:26:36 | 0:26:39 | |

The elephant manages to live on what is probably | 0:26:44 | 0:26:47 | |

the poorest diet of any mammal. | 0:26:47 | 0:26:50 | |

Although it welcomes leaves when it can get them, | 0:26:52 | 0:26:55 | |

it also eats the most fibrous browse of all - twigs, bark, even branches. | 0:26:55 | 0:27:00 | |

But again its huge intestines allow it | 0:27:00 | 0:27:03 | |

to give this roughage prolonged chemical treatment. | 0:27:03 | 0:27:06 | |

Our food takes about a day to pass through our bodies. | 0:27:06 | 0:27:09 | |

An elephant's takes two and a half days. | 0:27:09 | 0:27:12 | |

For most of that time, the browse, | 0:27:12 | 0:27:14 | |

having been mashed by the elephant's molars, | 0:27:14 | 0:27:16 | |

is stewing in the digestive juices | 0:27:16 | 0:27:19 | |

and bacterial broth of its gigantic gut. | 0:27:19 | 0:27:23 | |

Forest antelopes also moved out into the open country, | 0:27:28 | 0:27:31 | |

lured by so much readily available vegetation. | 0:27:31 | 0:27:35 | |

The little dik-dik resembles | 0:27:37 | 0:27:39 | |

the early forest-living antelopes in many ways. | 0:27:39 | 0:27:42 | |

Like them, it's small, only a foot high, | 0:27:42 | 0:27:44 | |

which is convenient for moving in thick vegetation. | 0:27:44 | 0:27:48 | |

And it lives in pairs, | 0:27:48 | 0:27:49 | |

for the shaded floor of the tropical forest is poor in leaves | 0:27:49 | 0:27:53 | |

and can't sustain a dense population of leaf-eaters. | 0:27:53 | 0:27:57 | |

So the antelopes living there | 0:27:57 | 0:27:59 | |

mark and defend their precious pastures against rivals. | 0:27:59 | 0:28:03 | |

The male deposits musk from a gland beneath his eye on twigs | 0:28:08 | 0:28:12 | |

by poking the tips actually in the gland. | 0:28:12 | 0:28:16 | |

The scent proclaims that | 0:28:17 | 0:28:19 | |

the territory belongs to a particular pair, | 0:28:19 | 0:28:21 | |

which will remain here together throughout their lives. | 0:28:21 | 0:28:25 | |

Another male reads the signs. | 0:28:25 | 0:28:28 | |

Smell is very important to the dik-dik. | 0:28:28 | 0:28:31 | |

They have other scent glands between their hooves, | 0:28:31 | 0:28:34 | |

which probably mark the trails. | 0:28:34 | 0:28:37 | |

Since the pair never stray from this one patch of land, | 0:28:37 | 0:28:40 | |

they know it intimately, and that's important in defence. | 0:28:40 | 0:28:43 | |

When danger approaches, | 0:28:43 | 0:28:46 | |

they know the best escape routes, the best corners in which to hide. | 0:28:46 | 0:28:49 | |

Impala inhabit more open country. | 0:28:58 | 0:29:01 | |

They no longer live in pairs, | 0:29:01 | 0:29:03 | |

but have formed herds for safety's sake. | 0:29:03 | 0:29:06 | |

It's very difficult to take them by surprise. | 0:29:06 | 0:29:09 | |

When they are attacked, | 0:29:13 | 0:29:15 | |

the herd works together to baffle their assailants. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:18 | |

As the animals suddenly leap in all directions, | 0:29:23 | 0:29:26 | |

a hunter may well hesitate in deciding which it should follow, | 0:29:26 | 0:29:29 | |

and that may make the difference between a killing and an escape. | 0:29:29 | 0:29:34 | |

Impala still prefer country containing bushes and trees, | 0:30:01 | 0:30:06 | |

but some grazers spend all their lives exposed | 0:30:06 | 0:30:09 | |

out on the open plain, where there is no cover of any kind. | 0:30:09 | 0:30:14 | |

The wildebeest form some of the greatest herds of all. | 0:30:25 | 0:30:29 | |

Tens of thousands of animals move across the plains, | 0:30:29 | 0:30:32 | |

sometimes making huge journeys to follow the rains | 0:30:32 | 0:30:36 | |

and find the newly springing grass. | 0:30:36 | 0:30:38 | |

In vast assemblages like these, | 0:30:38 | 0:30:41 | |

there are no pairs of males and females. | 0:30:41 | 0:30:44 | |

During the rutting season | 0:30:44 | 0:30:45 | |

the dominant bulls will set up small stamping grounds, | 0:30:45 | 0:30:48 | |

which the females will visit one after the other. | 0:30:48 | 0:30:51 | |

So a single bull will service many cows | 0:30:51 | 0:30:54 | |

and then lose touch with them as individuals | 0:30:54 | 0:30:58 | |

when they return to the anonymity of the herd. | 0:30:58 | 0:31:01 | |

Not surprisingly, this immense concentration of animals, | 0:31:01 | 0:31:04 | |

this vast reserve of meat, attracts the attention of hunters. | 0:31:04 | 0:31:09 | |

The cheetah relies on speed in a straightforward chase. | 0:31:12 | 0:31:16 | |

It's said to be the fastest runner in the world, | 0:31:16 | 0:31:19 | |

capable of reaching 70 miles, 110km an hour. | 0:31:19 | 0:31:23 | |

Its legs are not as long as an antelope's, | 0:31:23 | 0:31:25 | |

but it increases their effective length | 0:31:25 | 0:31:27 | |

with a backbone that's extremely flexible, | 0:31:27 | 0:31:29 | |

so that it can take huge strides. | 0:31:29 | 0:31:33 | |

But it can't sprint like this for long. | 0:31:34 | 0:31:36 | |

If it doesn't catch its prey within a quarter of a mile, | 0:31:36 | 0:31:39 | |

it has to give up exhausted. | 0:31:39 | 0:31:42 | |

And this time, the gazelle has won. | 0:31:46 | 0:31:48 | |

Young wildebeest are often taken by cheetah. | 0:31:54 | 0:31:57 | |

This cheetah is one of a pair of males | 0:32:13 | 0:32:16 | |

strolling through the herds, as if selecting their meal for the day. | 0:32:16 | 0:32:21 | |

Oddly, perhaps, the wildebeest seem little concerned. | 0:32:43 | 0:32:46 | |

Perhaps they know from the way the cheetahs are behaving | 0:32:46 | 0:32:49 | |

that they're not about to attack yet. | 0:32:49 | 0:32:53 | |

One male makes a tentative run. | 0:33:04 | 0:33:08 | |

Bending his supple spine, | 0:33:08 | 0:33:09 | |

he can cover an astonishing 23 feet, seven metres, | 0:33:09 | 0:33:13 | |

in a single bound. | 0:33:13 | 0:33:15 | |

It may be that by chivvying them in this way | 0:33:20 | 0:33:23 | |

the cheetahs are trying to pick out | 0:33:23 | 0:33:25 | |

the animal that is just a little slower than the others, | 0:33:25 | 0:33:28 | |

just a little more vulnerable. | 0:33:28 | 0:33:30 | |

His jaws are clenched on its windpipe, | 0:34:44 | 0:34:47 | |

and the wildebeest dies throttled. | 0:34:47 | 0:34:50 | |

The other male comes to share the catch. | 0:34:51 | 0:34:55 | |

Cheetahs, like most hunting species, | 0:35:20 | 0:35:22 | |

rarely tackle prey larger than themselves. | 0:35:22 | 0:35:25 | |

But lions are not so restricted. They are social hunters. | 0:35:25 | 0:35:30 | |

They're the biggest, | 0:35:30 | 0:35:31 | |

the heaviest of all the hunters on the plains, | 0:35:31 | 0:35:34 | |

and they live in groups, usually about 15-strong, | 0:35:34 | 0:35:38 | |

though sometimes there may be over 30 in a pride. | 0:35:38 | 0:35:41 | |

They're not as fast as the cheetah, | 0:35:49 | 0:35:51 | |

about 35 miles an hour is their top speed, | 0:35:51 | 0:35:53 | |

and out in the open they're no threat to the herds. | 0:35:53 | 0:35:57 | |

The zebras can keep their distance. | 0:35:57 | 0:35:59 | |

Provided they've got this amount of a start in a chase, | 0:35:59 | 0:36:03 | |

the lions will never catch them. | 0:36:03 | 0:36:05 | |

The lions' only chance is to get really close | 0:36:09 | 0:36:12 | |

and then rely on their spectacular acceleration. | 0:36:12 | 0:36:17 | |

Now one lioness begins to stalk, | 0:36:17 | 0:36:20 | |

keeping low and almost invisible in the tawny, sun-withered grass. | 0:36:20 | 0:36:25 | |

The zebra spot her. | 0:36:33 | 0:36:35 | |

Ahead there are other members of the pride. | 0:36:44 | 0:36:47 | |

In their panic, the zebra run towards them, | 0:36:47 | 0:36:50 | |

and now they take up the hunt. | 0:36:50 | 0:36:52 | |

But though she's got hold of it, she can't overpower it by herself. | 0:37:01 | 0:37:05 | |

The others come to her aid. | 0:37:05 | 0:37:08 | |

Now there is food, not just for one hunter, but for the whole pride. | 0:37:18 | 0:37:24 | |

Lions, hunting in groups like this, | 0:37:24 | 0:37:26 | |

kill on average once in every three attempts. | 0:37:26 | 0:37:30 | |

But lions do not always work in groups. | 0:37:37 | 0:37:40 | |

Sometimes a lioness will set out by herself. | 0:37:40 | 0:37:43 | |

Only one in five of these solitary hunts is successful. | 0:38:20 | 0:38:24 | |

Scavenging is a much easier way of getting meat. | 0:38:24 | 0:38:27 | |

Hyenas killed this wildebeest, | 0:38:27 | 0:38:29 | |

but a lioness, so much bigger than they are, | 0:38:29 | 0:38:31 | |

can chase them off if there are only a few of them. | 0:38:31 | 0:38:35 | |

Hyenas are small, and they can only run half as fast as the cheetah, | 0:38:52 | 0:38:57 | |

but they make up for that by hunting as a pack. | 0:38:57 | 0:39:00 | |

They have enormous stamina | 0:39:00 | 0:39:01 | |

and can keep up a good speed for a long time, | 0:39:01 | 0:39:04 | |

harrying and wearing down their quarry. | 0:39:04 | 0:39:07 | |

When a pack finally closes in on a wildebeest, there is no escape. | 0:39:13 | 0:39:18 | |

Few creatures can defeat hyenas as long as they work as a team. | 0:40:08 | 0:40:13 | |

A determined pack can even rob a lioness of her kill. | 0:40:13 | 0:40:17 | |

She gives up. Perhaps she'd had enough anyway. | 0:40:33 | 0:40:37 | |

So the pack and teamwork wins again. | 0:40:59 | 0:41:03 | |

Sometimes, though, pack disputes with pack. | 0:41:08 | 0:41:11 | |

This kill was made on the border between the hunting grounds | 0:41:11 | 0:41:14 | |

of two neighbouring packs. | 0:41:14 | 0:41:16 | |

The squabble surges this way and that, | 0:41:16 | 0:41:18 | |

as each gains temporary control of the carcass. | 0:41:18 | 0:41:22 | |

The females of the pack have their own dens where they raise the cubs. | 0:41:42 | 0:41:46 | |

A pack may contain as many as 80 animals. | 0:41:46 | 0:41:49 | |

They communicate with one another in the most comprehensive way, | 0:41:49 | 0:41:53 | |

using sound, gesture and smell. | 0:41:53 | 0:41:56 | |

The tail is particularly eloquent. | 0:41:57 | 0:42:00 | |

Normally it's carried curved down. | 0:42:00 | 0:42:02 | |

Erect like this, it's a sign of aggression. | 0:42:02 | 0:42:05 | |

This female is unsure about her rival. | 0:42:05 | 0:42:09 | |

Now she's happier. | 0:42:15 | 0:42:18 | |

From a very early age, each hyena marks grass stems | 0:42:20 | 0:42:24 | |

with scent from a gland beneath its tail. | 0:42:24 | 0:42:26 | |

When members of the pack meet, | 0:42:35 | 0:42:37 | |

they greet one another with extravagant smells and licks. | 0:42:37 | 0:42:41 | |

Each animal knows its fellows individually, | 0:42:41 | 0:42:44 | |

and each knows its place within the complex hierarchy of the pack. | 0:42:44 | 0:42:49 | |

This elaborate social structure with leaders and followers | 0:42:54 | 0:42:58 | |

and a highly effective system | 0:42:58 | 0:43:00 | |

of communication, on which it's based, | 0:43:00 | 0:43:02 | |

enables the pack to hunt most effectively as a team. | 0:43:02 | 0:43:05 | |

So that the hyenas, small though they may be, | 0:43:05 | 0:43:08 | |

are among the most effective killers on the plains. | 0:43:08 | 0:43:11 | |

Indeed in some parts it's the hyenas, hunting at night, | 0:43:11 | 0:43:15 | |

that are responsible for the majority of the kills. | 0:43:15 | 0:43:19 | |

Lion society also has a well-defined structure. | 0:43:28 | 0:43:32 | |

The females are the basis of the pride. | 0:43:32 | 0:43:34 | |

There may be a dozen or so of them, | 0:43:34 | 0:43:37 | |

and they are probably all sisters or half-sisters. | 0:43:37 | 0:43:40 | |

They cooperate with one another, | 0:43:47 | 0:43:49 | |

even, on occasion, suckling one another's cubs. | 0:43:49 | 0:43:53 | |

These lionesses will remain together throughout their lives. | 0:44:17 | 0:44:22 | |

The males come from other groups elsewhere to join them. | 0:44:22 | 0:44:25 | |

But once the males are accepted as members of the pride, | 0:44:25 | 0:44:28 | |

they take over much of the responsibility | 0:44:28 | 0:44:30 | |

for defending the territory, | 0:44:30 | 0:44:32 | |

roaring their claims of possession and fighting off intruders. | 0:44:32 | 0:44:37 | |

The females do most of the hunting, | 0:44:37 | 0:44:39 | |

but that doesn't take up much of their time. | 0:44:39 | 0:44:42 | |

Meat is much more nourishing than grass. | 0:44:42 | 0:44:44 | |

A lion can eat as much as 20 kilos at a sitting, | 0:44:44 | 0:44:48 | |

so a single meal will last it two days or even longer. | 0:44:48 | 0:44:52 | |

For the rest of the time there's not much to do | 0:45:09 | 0:45:12 | |

except watch the wildebeest herds | 0:45:12 | 0:45:14 | |

gathering their great quantities of grass. | 0:45:14 | 0:45:16 | |

Eventually the time comes when more meat is needed, | 0:46:21 | 0:46:25 | |

and the pride must hunt again. | 0:46:25 | 0:46:27 | |

The male is not to be disturbed. | 0:46:29 | 0:46:31 | |

He'll follow later when all the work has been done, | 0:46:31 | 0:46:34 | |

and probably just as well. | 0:46:34 | 0:46:35 | |

With a great mane, he's much more conspicuous than they. | 0:46:35 | 0:46:39 | |

The wildebeest have come down | 0:46:55 | 0:46:57 | |

to feed on the lush grass beside a marsh. | 0:46:57 | 0:47:00 | |

The lionesses spread out in line. | 0:47:07 | 0:47:10 | |

The herd won't run into the marsh that lies beyond. | 0:47:44 | 0:47:48 | |

It's a barrier they can be trapped against. | 0:47:48 | 0:47:50 | |

This lioness leaves the main group | 0:47:59 | 0:48:02 | |

and walks off to the far flank of the herd. | 0:48:02 | 0:48:05 | |

The others slowly advance on the wildebeest, | 0:48:08 | 0:48:11 | |

which move nearer the marsh. | 0:48:11 | 0:48:13 | |

Each lioness seems to keep a close watch on her companions | 0:48:29 | 0:48:32 | |

as they advance together closer and closer. | 0:48:32 | 0:48:37 | |

If the wildebeest get agitated, | 0:48:50 | 0:48:52 | |

the lions simply sit and wait for them to settle again, | 0:48:52 | 0:48:55 | |

which they do just a little nearer the marsh. | 0:48:55 | 0:48:58 | |

Now the ambush is laid. | 0:49:55 | 0:49:58 | |

Back and forth the wildebeest dash in panic and confusion, | 0:50:20 | 0:50:24 | |

and the lionesses have time to select their prey. | 0:50:24 | 0:50:27 | |

Once again jaws are clenched on a throat, | 0:51:19 | 0:51:22 | |

and a wildebeest is throttled. | 0:51:22 | 0:51:26 | |

By the time the others, including the male, arrive, it's dead. | 0:51:26 | 0:51:31 | |

The hunt has produced two kills. | 0:52:04 | 0:52:06 | |

That's more than enough meat for the whole pride. | 0:52:06 | 0:52:11 | |

So the long duels between hunter and hunted fought out on the open plain | 0:52:36 | 0:52:40 | |

led to a great development of teamwork and communication. | 0:52:40 | 0:52:45 | |

One animal came out of the forest to hunt on the plains | 0:52:45 | 0:52:48 | |

that I've not yet mentioned. | 0:52:48 | 0:52:49 | |

That's a particularly interesting one to us, | 0:52:49 | 0:52:52 | |

because it was our ancestor. | 0:52:52 | 0:52:54 | |

To trace it from its origins, we'll have to go back into the forest, | 0:52:54 | 0:52:58 | |

where its cousins still live. | 0:52:58 | 0:53:01 |