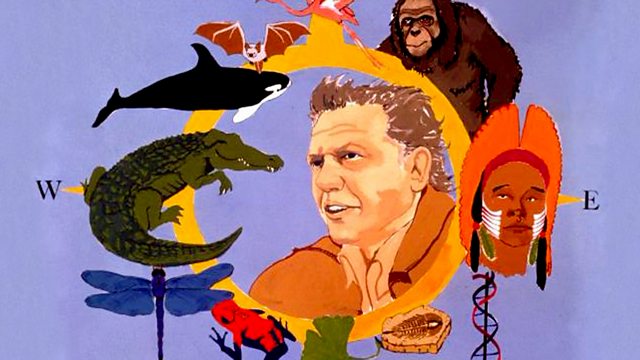

Life in the Trees Life on Earth

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Life in the Trees. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

If you spend your life clambering about in trees, | 0:01:13 | 0:01:17 | |

two of the most useful things to have | 0:01:17 | 0:01:19 | |

are a pair of hands, with which to grip the branches, | 0:01:19 | 0:01:23 | |

and a pair of eyes, which face forward | 0:01:23 | 0:01:26 | |

and both can focus on the same thing | 0:01:26 | 0:01:28 | |

so that you can accurately judge the distance of, say, | 0:01:28 | 0:01:32 | |

the next branch on which you want to jump or swing. | 0:01:32 | 0:01:36 | |

There are about 200 different kinds of animals in the world | 0:01:36 | 0:01:39 | |

that have those two characteristics. | 0:01:39 | 0:01:42 | |

We group them together and call them primates, | 0:01:42 | 0:01:45 | |

and they include monkeys, apes, man... | 0:01:45 | 0:01:49 | |

..and those creatures over there, | 0:01:51 | 0:01:53 | |

that I'm watching in this tree in Madagascar. | 0:01:53 | 0:01:56 | |

At first sight, this animal doesn't look much like a monkey. | 0:02:04 | 0:02:07 | |

That bushy, ringed tail is more like a cat's. | 0:02:07 | 0:02:11 | |

And the long snout, with moist, bare skin around the nostrils, | 0:02:16 | 0:02:21 | |

gives it a rather dog-like look. | 0:02:21 | 0:02:23 | |

But its hands give away its true character. | 0:02:23 | 0:02:26 | |

No dog or cat has a grasp like this. | 0:02:26 | 0:02:29 | |

This creature is a true primate and one of the most primitive ones. | 0:02:33 | 0:02:37 | |

It's a lemur. | 0:02:37 | 0:02:39 | |

Lemurs are descended from shrew-like mammals | 0:02:48 | 0:02:51 | |

that scampered along the ground at the end of the age of the dinosaurs. | 0:02:51 | 0:02:55 | |

And this lemur, the ring-tail, | 0:02:55 | 0:02:57 | |

is as much at home on the ground as it is in the trees. | 0:02:57 | 0:03:01 | |

They still retain old habits more suited for ground-dwelling, | 0:03:01 | 0:03:05 | |

like scent-marking. | 0:03:05 | 0:03:07 | |

The males have horny spurs on their wrists, surrounded by glands. | 0:03:07 | 0:03:11 | |

And they click these against saplings, | 0:03:12 | 0:03:14 | |

so impregnating the scratch with musk. | 0:03:14 | 0:03:17 | |

The female smears musk from a gland beneath her tail. | 0:03:19 | 0:03:23 | |

Males find this especially attractive. | 0:03:28 | 0:03:30 | |

Having checked, he marks over the same spots himself. | 0:03:36 | 0:03:40 | |

Frequent marking enables a troop | 0:03:43 | 0:03:46 | |

to leave a scent record of its movements, | 0:03:46 | 0:03:48 | |

and so establish rights of way on the forest floor. | 0:03:48 | 0:03:51 | |

An angry male spreads scent onto his tail | 0:03:56 | 0:03:59 | |

by drawing it over his wrist and chest glands, | 0:03:59 | 0:04:01 | |

for perfume is also used in the battle for dominance. | 0:04:01 | 0:04:04 | |

He will then thrash it in the air | 0:04:11 | 0:04:13 | |

so that the scent is wafted towards his opponent, to intimidate him. | 0:04:13 | 0:04:17 | |

The lower male recharges his tail. | 0:04:23 | 0:04:26 | |

Grasping hands, so valuable to the adult | 0:04:31 | 0:04:33 | |

for holding on to branches, are also useful to the young. | 0:04:33 | 0:04:37 | |

Baby squirrels and tree shrews, with straightforward paws, | 0:04:37 | 0:04:40 | |

have to be deposited in nests of some kind | 0:04:40 | 0:04:43 | |

and are often abandoned while the parents gather food. | 0:04:43 | 0:04:46 | |

But lemurs have a different technique. | 0:04:46 | 0:04:48 | |

The little ones can close their fists on their parents' fur | 0:04:48 | 0:04:51 | |

and so accompany them wherever they go. | 0:04:51 | 0:04:54 | |

Lemurs were in their heyday about 40 to 50 million years ago. | 0:05:01 | 0:05:08 | |

Their fossils have been found in not only Africa, but Europe. | 0:05:08 | 0:05:13 | |

And about that time, | 0:05:13 | 0:05:14 | |

Madagascar became separated from the east coast of Africa. | 0:05:14 | 0:05:19 | |

There were lemurs living there, too, of course, | 0:05:19 | 0:05:21 | |

but because they were now living on an island, | 0:05:21 | 0:05:24 | |

they were protected from competition | 0:05:24 | 0:05:26 | |

with other, more intelligent, more efficient creatures | 0:05:26 | 0:05:29 | |

that were to develop elsewhere in the world later. | 0:05:29 | 0:05:32 | |

And so Madagascar became what it is now, a paradise for lemurs. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:37 | |

As well as the ring-tail, there are over 20 different kinds of lemurs, | 0:05:37 | 0:05:42 | |

each one adapted to a particular kind of life in the trees. | 0:05:42 | 0:05:46 | |

Down here in the south of the island, in this extraordinary spiny forest, | 0:05:46 | 0:05:51 | |

there is one that specialises in jumping. | 0:05:51 | 0:05:53 | |

It's called a sifaka. | 0:06:01 | 0:06:03 | |

And you could hardly fine a better demonstrator | 0:06:03 | 0:06:05 | |

of those two invaluable primate talents, | 0:06:05 | 0:06:08 | |

the ability to judge the distance of a jump | 0:06:08 | 0:06:10 | |

and to grasp a hold when you land. | 0:06:10 | 0:06:13 | |

The disproportionately long hind legs | 0:07:02 | 0:07:04 | |

that enable them to jump between trees so well | 0:07:04 | 0:07:07 | |

make walking on all fours impossible. | 0:07:07 | 0:07:09 | |

Another accomplished leaper | 0:07:29 | 0:07:31 | |

lives in the forests of north-east Madagascar, | 0:07:31 | 0:07:34 | |

but there it's more often heard than seen. | 0:07:34 | 0:07:37 | |

HAUNTING CALLS ECHO | 0:07:37 | 0:07:40 | |

The indri, the largest of the lemurs. | 0:07:40 | 0:07:42 | |

And it's no accident that it has a well-developed voice. | 0:07:42 | 0:07:46 | |

MOURNFUL CALLS CONTINUE | 0:07:48 | 0:07:51 | |

The thick canopy, in which the indri lives, | 0:08:02 | 0:08:05 | |

has turned it into a chorister. | 0:08:05 | 0:08:07 | |

Perhaps scent is too easily dispersed up here. | 0:08:07 | 0:08:10 | |

It's certainly difficult to see far. | 0:08:10 | 0:08:13 | |

So, safe from attack by predators, | 0:08:13 | 0:08:15 | |

it's much easier and more effective to use sound | 0:08:15 | 0:08:18 | |

to carry messages through the forest, to claim a territory | 0:08:18 | 0:08:21 | |

and register your whereabouts with your neighbours. | 0:08:21 | 0:08:24 | |

And few creatures do so more deafeningly than a family of indris. | 0:08:30 | 0:08:35 | |

IT WAILS LOUDLY | 0:08:35 | 0:08:38 | |

Other lemurs also use their voices to keep in touch with the troop. | 0:08:51 | 0:08:55 | |

These are brown lemurs. | 0:08:55 | 0:08:57 | |

IT GRUNTS | 0:08:57 | 0:09:00 | |

They often travel with the ring-tails, | 0:09:05 | 0:09:07 | |

which supplement their elaborate system of scent signals | 0:09:07 | 0:09:10 | |

with a repertoire of calls, | 0:09:10 | 0:09:12 | |

especially when the troop is on the move. | 0:09:12 | 0:09:15 | |

LEMURS GRUNT AND CALL | 0:09:15 | 0:09:18 | |

Out in the open, where they're more at risk, | 0:09:22 | 0:09:24 | |

the ring-tails keep together | 0:09:24 | 0:09:26 | |

and raise their vividly-marked tails like flags, | 0:09:26 | 0:09:29 | |

so that the members of the troop | 0:09:29 | 0:09:30 | |

can also maintain visual contact with one another. | 0:09:30 | 0:09:33 | |

This troop is going down to the river to drink. | 0:09:45 | 0:09:48 | |

LEMURS CHATTER AND CALL | 0:10:02 | 0:10:07 | |

As darkness approaches, | 0:10:07 | 0:10:09 | |

the forest rings to the sound of the lemur groups, | 0:10:09 | 0:10:12 | |

spacing themselves out as they settle down in the trees to sleep. | 0:10:12 | 0:10:16 | |

A VARIETY OF LEMURS CALL | 0:10:16 | 0:10:20 | |

Many lemurs are nocturnal, and when darkness falls | 0:10:24 | 0:10:28 | |

a completely new cast of them appears. | 0:10:28 | 0:10:31 | |

This is the smallest of all, little bigger than a mouse, | 0:10:31 | 0:10:33 | |

and CALLED a mouse lemur. | 0:10:33 | 0:10:35 | |

It eats insects as well as seeds and fruit | 0:10:40 | 0:10:43 | |

and enthusiastically marks its own section of a tree | 0:10:43 | 0:10:46 | |

by urinating on its hands | 0:10:46 | 0:10:47 | |

and planting smelly hand-prints all along the branches. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:51 | |

The rarest lemur, the aye-aye. | 0:10:55 | 0:10:57 | |

It may be on the verge of extinction. | 0:10:57 | 0:10:59 | |

A few still survive, but no-one knows how many. | 0:10:59 | 0:11:02 | |

It's the oddest of the lot, | 0:11:06 | 0:11:08 | |

gnawing into wood to expose beetle grubs. | 0:11:08 | 0:11:11 | |

It also has a taste for egg yolk, which it gets | 0:11:11 | 0:11:14 | |

by using its extraordinary long, bony middle finger as a probe. | 0:11:14 | 0:11:17 | |

In all, there are some 20 different species of lemur | 0:11:28 | 0:11:31 | |

still surviving in Madagascar. | 0:11:31 | 0:11:33 | |

Elsewhere in the world, however, the lemurs died out. | 0:11:34 | 0:11:38 | |

It seems they couldn't face the competition | 0:11:38 | 0:11:41 | |

from more advanced primates that were to develop later - | 0:11:41 | 0:11:45 | |

the monkeys. | 0:11:45 | 0:11:46 | |

That competition only came during the day | 0:11:46 | 0:11:49 | |

because, with one exception, all monkeys sleep at night. | 0:11:49 | 0:11:53 | |

And so the lemurs were able to survive by being nocturnal. | 0:11:53 | 0:11:59 | |

In Africa, there are the bushbabies, | 0:11:59 | 0:12:01 | |

which are very similar to the mouse lemurs of Madagascar. | 0:12:01 | 0:12:03 | |

There's also the potto. | 0:12:03 | 0:12:05 | |

And here, in the forests of the Far East, in Malaysia, | 0:12:05 | 0:12:09 | |

there's the loris. | 0:12:09 | 0:12:10 | |

Once again, it has those primate hallmarks - | 0:12:14 | 0:12:17 | |

the forward-facing eyes and the grasping hands. | 0:12:17 | 0:12:21 | |

This is a young one. It had a firm grip right from birth, | 0:12:25 | 0:12:30 | |

and it uses it, as nearly all lemur babies do, | 0:12:30 | 0:12:33 | |

to cling to its mother's fur. | 0:12:33 | 0:12:35 | |

The loris still uses scent to mark its territory, | 0:12:44 | 0:12:47 | |

and it has the typical moist nose of a lemur, | 0:12:47 | 0:12:51 | |

with which to read the marks in the trees. | 0:12:51 | 0:12:53 | |

Only one primitive primate has no such nose, | 0:13:01 | 0:13:04 | |

and it, too, lives in these oriental forests. The tarsier. | 0:13:04 | 0:13:08 | |

For it, the dominant sense is not smell, but sight. | 0:13:08 | 0:13:12 | |

Its huge eyes and snub nose, without a surround of moist skin, | 0:13:16 | 0:13:21 | |

are signs of things to come, | 0:13:21 | 0:13:22 | |

for these are the characteristics of the more advanced primates | 0:13:22 | 0:13:26 | |

that displaced the lemurs and their relations from most of the world - | 0:13:26 | 0:13:29 | |

the monkeys. | 0:13:29 | 0:13:30 | |

The most primitive of the true monkeys still surviving | 0:13:35 | 0:13:38 | |

live in the jungles of South America. | 0:13:38 | 0:13:41 | |

Marmosets move about not at night, but during the day. | 0:13:41 | 0:13:45 | |

At first glance, they don't look like monkeys, | 0:13:45 | 0:13:48 | |

but scurry around the treetops more like squirrels. | 0:13:48 | 0:13:51 | |

They use visual signals a great deal. | 0:13:54 | 0:13:56 | |

Each species carries its own badges of identification - | 0:13:56 | 0:14:00 | |

moustaches, bonnets and plumes, | 0:14:00 | 0:14:02 | |

or, like these common marmosets, long, white ear tufts. | 0:14:02 | 0:14:05 | |

Although they eat fruit and insects, most of their food consists of gum, | 0:14:09 | 0:14:13 | |

which they tap by gnawing notches in bark. | 0:14:13 | 0:14:16 | |

Their gum trees are important features of their territories | 0:14:25 | 0:14:28 | |

and must be protected at all costs. | 0:14:28 | 0:14:30 | |

And the marmosets do this by marking them with scented urine. | 0:14:30 | 0:14:34 | |

Each territory is occupied | 0:14:41 | 0:14:43 | |

by an adult male and female together their young, | 0:14:43 | 0:14:46 | |

some of which may be nearly full-grown. | 0:14:46 | 0:14:49 | |

They all travel together | 0:14:49 | 0:14:50 | |

and defend the boundaries against neighbouring families. | 0:14:50 | 0:14:53 | |

Sometimes shrieking will scare off trespassers. | 0:14:54 | 0:14:58 | |

HIGH-PITCHED SQUEAKS | 0:14:58 | 0:15:00 | |

And, if that fails, they back up their threat | 0:15:02 | 0:15:04 | |

with a truly spectacular genital display. | 0:15:04 | 0:15:07 | |

To marmosets, this is the ultimate threat, | 0:15:10 | 0:15:13 | |

and the trespassing family nearly always withdraws. | 0:15:13 | 0:15:16 | |

So, through the evolution of a language of signals, | 0:15:20 | 0:15:23 | |

damaging fights are more often than not avoided. | 0:15:23 | 0:15:26 | |

Like lemur babies, | 0:15:36 | 0:15:37 | |

young marmosets have got a firm and determined grasp, | 0:15:37 | 0:15:41 | |

and they cling to their parents right from birth. | 0:15:41 | 0:15:43 | |

Often it's the male who carries them, | 0:15:43 | 0:15:46 | |

but again, like the lemurs, | 0:15:46 | 0:15:48 | |

the youngsters tend to move around a good deal, from one adult to another, | 0:15:48 | 0:15:52 | |

and even onto the backs of their older brothers and sisters. | 0:15:52 | 0:15:55 | |

And a particularly patient and long-suffering one | 0:15:55 | 0:15:58 | |

will accumulate a heavy load. | 0:15:58 | 0:16:00 | |

The grasping hands, so good at clinging to fur and branches, | 0:16:23 | 0:16:27 | |

are also excellent combs. | 0:16:27 | 0:16:30 | |

The nimble fingers are used for picking parasites | 0:16:30 | 0:16:32 | |

and loose skin from the fur of others. | 0:16:32 | 0:16:34 | |

Marmosets are the smallest of the monkeys | 0:16:37 | 0:16:39 | |

and, in many ways, they represent a link | 0:16:39 | 0:16:41 | |

between lemurs and other monkeys like these. | 0:16:41 | 0:16:44 | |

The squirrel monkey, also a South American, | 0:16:49 | 0:16:52 | |

is a typical member of the monkey family. | 0:16:52 | 0:16:55 | |

Active during the day, | 0:16:55 | 0:16:56 | |

relying more on its eyes and ears than its nose | 0:16:56 | 0:16:59 | |

for finding its way about and for communicating with its fellows. | 0:16:59 | 0:17:03 | |

Lively, gymnastic and totally at home in the trees. | 0:17:03 | 0:17:07 | |

There are about 70 different species of monkey in South America alone. | 0:17:21 | 0:17:26 | |

None of them is better adapted to life in the trees | 0:17:26 | 0:17:29 | |

than these howlers. | 0:17:29 | 0:17:31 | |

They sleep in the treetops | 0:17:34 | 0:17:35 | |

with a confident disregard for height and the risk of falling, | 0:17:35 | 0:17:39 | |

and they usually wait for the sun to get well up | 0:17:39 | 0:17:42 | |

before they bother to stir. | 0:17:42 | 0:17:43 | |

THEY GRUNT | 0:17:43 | 0:17:47 | |

Then they begin to demonstrate why they get their name. | 0:18:00 | 0:18:04 | |

HOARSE HOWLING | 0:18:04 | 0:18:07 | |

THE HOWLING GETS LOUDER | 0:18:12 | 0:18:17 | |

The howlers and that most tree-loving of lemurs, the indri, | 0:18:45 | 0:18:49 | |

have both discovered that the most efficient way | 0:18:49 | 0:18:52 | |

to lay claim to a large area of the treetops is to sing. | 0:18:52 | 0:18:56 | |

The howlers have taken the technique to extremes - | 0:18:56 | 0:18:59 | |

Their chorus is said to be the loudest noise made by any mammal. | 0:18:59 | 0:19:03 | |

With a favourable wind, you can hear them five kilometres away. | 0:19:03 | 0:19:07 | |

These are the biggest and heaviest monkeys in South America, | 0:19:08 | 0:19:12 | |

20 times the weight of a marmoset. | 0:19:12 | 0:19:15 | |

There seems to be a tendency among primates, | 0:19:15 | 0:19:17 | |

as in most mammals, to become larger and larger. | 0:19:17 | 0:19:21 | |

This may be because when males dispute over females, | 0:19:21 | 0:19:24 | |

the biggest one, from sheer strength, | 0:19:24 | 0:19:26 | |

is likely to win and so will father bigger babies. | 0:19:26 | 0:19:30 | |

But an increase in size, when you live in trees, has one drawback - | 0:19:30 | 0:19:34 | |

it becomes increasingly difficult to reach the outer branches | 0:19:34 | 0:19:37 | |

to gather fruit and leaves or to move from one tree to another. | 0:19:37 | 0:19:42 | |

The howlers have a way of reducing the problem, | 0:19:42 | 0:19:45 | |

an additional climbing aid of marvellous effectiveness, | 0:19:45 | 0:19:49 | |

a grasping tail. | 0:19:49 | 0:19:50 | |

They need to be very agile, for they are total vegetarians, | 0:20:17 | 0:20:21 | |

and the best fruit and leaves | 0:20:21 | 0:20:22 | |

are always at the farthest end of the branches. | 0:20:22 | 0:20:26 | |

Like all monkeys, their sense of smell is relatively dull. | 0:20:44 | 0:20:48 | |

So, to tell whether a fruit is ripe or not, | 0:20:48 | 0:20:51 | |

they have to hold it very close to the nose and give it a good sniff. | 0:20:51 | 0:20:55 | |

Some, though, are less fussy than others. | 0:21:08 | 0:21:10 | |

A howler selects fruit not only by smell, like a lemur, | 0:21:31 | 0:21:34 | |

but by its colour. | 0:21:34 | 0:21:35 | |

That is something that no lemur can do. | 0:21:35 | 0:21:38 | |

Most of them are virtually colour-blind. | 0:21:38 | 0:21:41 | |

But all the monkeys scampering about in the sunshine | 0:21:41 | 0:21:44 | |

have very good colour vision indeed. | 0:21:44 | 0:21:46 | |

And that has allowed them to use colour in their body language. | 0:21:46 | 0:21:50 | |

In fact, monkeys are the most vividly colourful of all mammals. | 0:21:50 | 0:21:54 | |

The monkeys' exploitation of colour is a worldwide characteristic. | 0:22:19 | 0:22:23 | |

But, from other points of view, there are considerable differences | 0:22:27 | 0:22:30 | |

between those species that live in South America | 0:22:30 | 0:22:34 | |

and those that live in the rest of the world. | 0:22:34 | 0:22:36 | |

Here in Africa, | 0:22:40 | 0:22:42 | |

the monkeys also developed into a multitude of different kinds. | 0:22:42 | 0:22:46 | |

But, for some reason that we don't really understand, | 0:22:46 | 0:22:49 | |

many species came down from the trees | 0:22:49 | 0:22:52 | |

and were almost as happy on the ground as they were in the branches. | 0:22:52 | 0:22:56 | |

Like, for example, these vervets. | 0:22:56 | 0:22:59 | |

This readiness to leave the trees may be something to do with the fact | 0:23:02 | 0:23:06 | |

that, for some reason, no African monkeys | 0:23:06 | 0:23:08 | |

have managed to develop that South American innovation, | 0:23:08 | 0:23:11 | |

the grasping tail. | 0:23:11 | 0:23:13 | |

So they never became so extremely adapted to a tree-living life, | 0:23:13 | 0:23:17 | |

or so thoroughly at home there. At any rate, the mere fact | 0:23:17 | 0:23:20 | |

that there are monkeys foraging over this grassland | 0:23:20 | 0:23:24 | |

is enough to tell you that this is an African scene. | 0:23:24 | 0:23:27 | |

There are lots of grasslands in South America, | 0:23:29 | 0:23:32 | |

but there are no monkeys wandering over them, like these. | 0:23:32 | 0:23:35 | |

There's even one kind of African monkey | 0:23:41 | 0:23:43 | |

that instead of always seeking safety in trees when danger threatens, | 0:23:43 | 0:23:47 | |

on occasion does just the reverse. | 0:23:47 | 0:23:49 | |

BABOONS CHATTER AND HOWL | 0:23:51 | 0:23:54 | |

These are baboons. | 0:24:03 | 0:24:05 | |

The physical talents that their ancestors developed in the trees | 0:24:05 | 0:24:08 | |

are still very useful on the ground. | 0:24:08 | 0:24:11 | |

The young baboon still clings to its mother's fur, | 0:24:11 | 0:24:14 | |

and as it gets older, rides on her back like a jockey. | 0:24:14 | 0:24:17 | |

Their grasping hands can pick up, pull up and dig up most things. | 0:24:21 | 0:24:27 | |

And baboons have developed a taste for a wide variety of food. | 0:24:27 | 0:24:30 | |

Not only the standard and typical monkey diet of fruit and leaves, | 0:24:30 | 0:24:34 | |

but roots and insects, and red meat, | 0:24:34 | 0:24:37 | |

in the form of lizards and small rodents, | 0:24:37 | 0:24:40 | |

and even other monkeys, if they can catch them. | 0:24:40 | 0:24:42 | |

Male baboons have grown big and powerful | 0:24:44 | 0:24:47 | |

in order to defend themselves and their troop. | 0:24:47 | 0:24:49 | |

But down on the ground there is also danger. | 0:24:55 | 0:24:58 | |

The big males keep order with visual signals. | 0:25:03 | 0:25:07 | |

BABOONS CALL AND GRUNT | 0:25:07 | 0:25:09 | |

The eyebrow flash is usually quite sufficient as a threat. | 0:25:17 | 0:25:21 | |

Though, every now and then, | 0:25:21 | 0:25:23 | |

it has to be backed up with a more obvious show of strength. | 0:25:23 | 0:25:27 | |

BABOONS SHRIEK AND CHATTER | 0:25:27 | 0:25:29 | |

Several other species of monkey, as well as the baboon, | 0:25:39 | 0:25:42 | |

have become very efficient at living on the ground. | 0:25:42 | 0:25:45 | |

One has even left Africa and emigrated to Europe. | 0:25:45 | 0:25:50 | |

The Rock of Gibraltar has been the home of troops of macaque monkeys | 0:25:50 | 0:25:53 | |

for about 2,000 years. | 0:25:53 | 0:25:55 | |

It's true that, in recent times, the British army | 0:25:55 | 0:25:58 | |

has imported fresh stock from North Africa when numbers got low, | 0:25:58 | 0:26:02 | |

and it seems likely that the very first ones here | 0:26:02 | 0:26:04 | |

were brought over from Africa as pets by Roman soldiers. | 0:26:04 | 0:26:08 | |

It says a lot for these monkeys that they've managed to survive. | 0:26:08 | 0:26:12 | |

Indeed, the macaque is one of the most resourceful | 0:26:12 | 0:26:15 | |

and adaptable of all monkeys. | 0:26:15 | 0:26:17 | |

In one form or another, it lives all over Asia, | 0:26:17 | 0:26:21 | |

from Afghanistan and India to Ceylon and Java, | 0:26:21 | 0:26:25 | |

and even as far north as Japan. | 0:26:25 | 0:26:27 | |

Up here, in the Japanese Alps, winters can be very severe indeed, | 0:26:36 | 0:26:41 | |

and the Japanese macaque has developed | 0:26:41 | 0:26:43 | |

a particularly dense and warm fur. | 0:26:43 | 0:26:45 | |

None of them hibernate, so they need to gather food every day. | 0:27:00 | 0:27:04 | |

And, at times like this, they have no alternative | 0:27:04 | 0:27:07 | |

but to burrow through the snow in search of it. | 0:27:07 | 0:27:09 | |

One population, however, has discovered | 0:27:30 | 0:27:33 | |

a most remarkable way of keeping themselves warm. | 0:27:33 | 0:27:36 | |

These are volcanic springs. | 0:27:43 | 0:27:46 | |

The monkeys moved into this area for the first time only a few years ago. | 0:27:46 | 0:27:50 | |

And one group of them quickly discovered you could get some relief | 0:27:50 | 0:27:53 | |

from blizzards and the worst of the cold | 0:27:53 | 0:27:55 | |

by sitting all day in a hot bath. | 0:27:55 | 0:27:58 | |

Unfortunately, though, there's no food to be found here, | 0:28:38 | 0:28:42 | |

so they have to come out sometimes, | 0:28:42 | 0:28:44 | |

and then it must be horribly chilly. | 0:28:44 | 0:28:46 | |

Macaques live in many parts of Japan. | 0:28:54 | 0:28:57 | |

And one population of them has become famous all over the world | 0:28:57 | 0:29:00 | |

for their inventiveness. | 0:29:00 | 0:29:03 | |

These live on a tiny offshore island called Koshima. | 0:29:03 | 0:29:07 | |

They're an isolated troop, | 0:29:07 | 0:29:09 | |

and they've made some remarkable changes in their behaviour. | 0:29:09 | 0:29:13 | |

For a long time people used to think that | 0:29:13 | 0:29:15 | |

the way in which creatures like these feed is largely instinctive. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:20 | |

But then, in 1952, scientists came to this island, | 0:29:20 | 0:29:24 | |

and in order to entice the monkeys out into the open | 0:29:24 | 0:29:27 | |

so that they could observe them more closely, | 0:29:27 | 0:29:29 | |

they started offering them... | 0:29:29 | 0:29:31 | |

THE MACAQUE SHRIEKS | 0:29:31 | 0:29:33 | |

..sweet potatoes. | 0:29:33 | 0:29:35 | |

Sweet potatoes, like that. | 0:29:35 | 0:29:37 | |

After about a year, a young female called Imo | 0:29:41 | 0:29:45 | |

began to take her roots down to a pool | 0:29:45 | 0:29:47 | |

and wash off the sand and mud before eating them. | 0:29:47 | 0:29:50 | |

Within a few weeks, friends and family, including her mother, | 0:29:50 | 0:29:54 | |

were copying her. | 0:29:54 | 0:29:55 | |

The habit spread and, ten years later, | 0:29:55 | 0:29:57 | |

almost all the monkeys on the island habitually wash their sweet potatoes. | 0:29:57 | 0:30:03 | |

Then a new variation arose. | 0:30:03 | 0:30:05 | |

Instead of using fresh water, | 0:30:09 | 0:30:11 | |

the monkeys took the roots down to the sea and washed them there, | 0:30:11 | 0:30:14 | |

even when they were clean already. | 0:30:14 | 0:30:16 | |

Perhaps they simply liked salt on their potatoes. | 0:30:16 | 0:30:20 | |

Only the very old didn't adopt the new customs. | 0:30:20 | 0:30:23 | |

The young were quick to learn. | 0:30:23 | 0:30:25 | |

And the fact that babies travelled on their mothers' back, | 0:30:25 | 0:30:28 | |

meant that they saw exactly what she was doing at all times, | 0:30:28 | 0:30:31 | |

an unexpected benefit of having grasping hands. | 0:30:31 | 0:30:35 | |

Then the scientists changed the diet to unhusked rice. | 0:30:35 | 0:30:39 | |

They wanted to keep the monkeys in one place | 0:30:39 | 0:30:41 | |

so that they could observe them | 0:30:41 | 0:30:43 | |

and they reckoned it would take them a long time | 0:30:43 | 0:30:45 | |

to pick out the rice from the sand, | 0:30:45 | 0:30:47 | |

but they'd reckoned without Imo. | 0:30:47 | 0:30:49 | |

She grabbed handfuls of rice and sand together | 0:30:49 | 0:30:52 | |

and threw the whole lot into the water. | 0:30:52 | 0:30:55 | |

The sand sank, the rice floated, and she quickly skimmed it off. | 0:30:55 | 0:30:59 | |

And, once again, the habit spread. | 0:30:59 | 0:31:01 | |

This ability and, indeed, readiness | 0:31:09 | 0:31:12 | |

to copy and learn from your contemporaries and your elders | 0:31:12 | 0:31:16 | |

results in the community having shared skills, shared knowledge, | 0:31:16 | 0:31:20 | |

shared ways of doing things, having, in fact, a shared culture. | 0:31:20 | 0:31:25 | |

The word, of course, is normally used for human societies, | 0:31:25 | 0:31:28 | |

but there's no reason, in principle, | 0:31:28 | 0:31:30 | |

why it shouldn't be applied to monkeys as well. | 0:31:30 | 0:31:32 | |

And what this troop of monkeys have done is to develop a simple culture. | 0:31:32 | 0:31:37 | |

Walking on your hind legs | 0:32:01 | 0:32:02 | |

is still very much a gymnastic trick for these creatures. | 0:32:02 | 0:32:06 | |

Monkeys are essentially four-footed animals. | 0:32:06 | 0:32:09 | |

There is one group of the primates that is, by and large, two-legged. | 0:32:09 | 0:32:13 | |

And, to see how they arose, | 0:32:13 | 0:32:15 | |

we have to go back to the tropical rainforests of the Old World. | 0:32:15 | 0:32:18 | |

Here, in the treetops of the jungles of the Far East, | 0:32:32 | 0:32:36 | |

monkeys developed that specialised in eating leaves and blossoms, | 0:32:36 | 0:32:39 | |

just like the howlers of South America. | 0:32:39 | 0:32:42 | |

The silver leaf monkey is one of them. | 0:32:47 | 0:32:51 | |

It's particularly unusual in that it's one of the few primates | 0:32:51 | 0:32:54 | |

whose young are totally different in colour from their parents. | 0:32:54 | 0:32:58 | |

This is just about the biggest totally tree-living monkey in Asia, | 0:33:03 | 0:33:07 | |

and it's still a considerable gymnast. | 0:33:07 | 0:33:10 | |

But some primates here have grown even bigger. | 0:33:25 | 0:33:29 | |

These heavyweights didn't solve their climbing problems | 0:33:29 | 0:33:32 | |

with a grasping tail. | 0:33:32 | 0:33:34 | |

Instead of running along the top of branches, | 0:33:34 | 0:33:36 | |

they took to swinging beneath them by their arms, | 0:33:36 | 0:33:39 | |

and they lost their tails altogether. | 0:33:39 | 0:33:42 | |

These are the apes. | 0:33:42 | 0:33:43 | |

The big ape of Borneo is the orang-utan. | 0:33:46 | 0:33:49 | |

Its toes have just as powerful a grip as its fingers. | 0:33:49 | 0:33:52 | |

In fact, you might, with justice, call it four-handed. | 0:33:52 | 0:33:55 | |

They're too big to jump about | 0:33:55 | 0:33:58 | |

and seldom let go with more than two limbs at a time. | 0:33:58 | 0:34:01 | |

They move across space by using their weight | 0:34:01 | 0:34:04 | |

and making a tree or vine sway in the direction that they want to go. | 0:34:04 | 0:34:08 | |

The males sometimes grow so enormous | 0:34:15 | 0:34:18 | |

that the thinner branches won't hold them at all. | 0:34:18 | 0:34:20 | |

They have to get from one tree to another | 0:34:20 | 0:34:23 | |

by descending and shambling across the ground. | 0:34:23 | 0:34:26 | |

Increase in size may have been the stimulus | 0:34:32 | 0:34:35 | |

to develop a swinging way of getting around. | 0:34:35 | 0:34:37 | |

But, having developed it, one ape, the gibbon, | 0:34:37 | 0:34:40 | |

exploited the new technique to its limit | 0:34:40 | 0:34:42 | |

by becoming smaller again. | 0:34:42 | 0:34:45 | |

The gibbon's arms are greatly lengthened and so are its fingers, | 0:34:45 | 0:34:48 | |

so that its hands have become hooks | 0:34:48 | 0:34:50 | |

that can be quickly latched onto a branch and off again. | 0:34:50 | 0:34:54 | |

With such limbs, | 0:34:56 | 0:34:58 | |

the gibbons have become the most exuberant and daring of acrobats | 0:34:58 | 0:35:01 | |

to be found anywhere. | 0:35:01 | 0:35:03 | |

THE GIBBONS WHOOP AND CRY | 0:35:03 | 0:35:07 | |

Such spectacular performances do, however, have risks. | 0:35:34 | 0:35:38 | |

Untested branches can break, | 0:35:38 | 0:35:40 | |

and, in fact, a third of all gibbon skeletons that have been examined | 0:35:40 | 0:35:44 | |

show signs of fractures. | 0:35:44 | 0:35:45 | |

There's one ape, however, that spends nearly all its time on the ground. | 0:36:04 | 0:36:08 | |

It lives here, 10,000 feet up, | 0:36:08 | 0:36:10 | |

on the flanks of the volcanoes of Central Africa | 0:36:10 | 0:36:14 | |

on the borders of Rwanda and Zaire. | 0:36:14 | 0:36:17 | |

It's the biggest of all the apes, the shyest, one of the rarest | 0:36:17 | 0:36:22 | |

and, until recently, one of the least-known. | 0:36:22 | 0:36:25 | |

The gorilla. | 0:36:25 | 0:36:26 | |

The group of gorillas that lives here | 0:36:28 | 0:36:30 | |

has been studied by scientists for several years | 0:36:30 | 0:36:32 | |

and has become sufficiently accustomed to human beings | 0:36:32 | 0:36:35 | |

to allow you to approach quite close. | 0:36:35 | 0:36:38 | |

But you have to behave properly, | 0:36:46 | 0:36:48 | |

and you mustn't conceal yourself too well. | 0:36:48 | 0:36:51 | |

If you appeared close to them and took them by surprise, | 0:36:51 | 0:36:54 | |

then they would almost certainly charge. | 0:36:54 | 0:36:57 | |

DEEP GRUNTING | 0:36:57 | 0:36:58 | |

There's a lookout sitting on that tree, and he's already seen me. | 0:37:05 | 0:37:09 | |

THE GORILLA GRUNTS | 0:37:15 | 0:37:17 | |

WHISPERING: There is more meaning and mutual understanding | 0:38:06 | 0:38:11 | |

in exchanging a glance with a gorilla... | 0:38:11 | 0:38:15 | |

..than any other animal I know. | 0:38:17 | 0:38:18 | |

We're so similar. | 0:38:20 | 0:38:22 | |

Their sight, their hearing, their sense of smell | 0:38:23 | 0:38:28 | |

are so similar to ours | 0:38:28 | 0:38:30 | |

that we see the world in the same way as they do. | 0:38:30 | 0:38:33 | |

They live in the same sort of social groups, | 0:38:35 | 0:38:39 | |

largely permanent family relationships. | 0:38:39 | 0:38:42 | |

They walk around on the ground as we do, though they're... | 0:38:43 | 0:38:46 | |

HOLLOW THUDS | 0:38:47 | 0:38:49 | |

..immensely more powerful than we are. | 0:38:49 | 0:38:51 | |

And so, if there were a possibility of... | 0:38:51 | 0:38:54 | |

..escaping the human condition and living imaginatively... | 0:38:55 | 0:38:59 | |

HE GROWLS SOFTLY | 0:39:02 | 0:39:03 | |

..in another creature's world... | 0:39:04 | 0:39:06 | |

..it must be with the gorilla. | 0:39:08 | 0:39:09 | |

And yet, as I sit here, surrounded by this... | 0:39:12 | 0:39:16 | |

trusting gorilla family... | 0:39:17 | 0:39:19 | |

They're gentle...placid creatures. | 0:39:21 | 0:39:26 | |

The boss of the group is that silverback male. | 0:39:27 | 0:39:31 | |

The rest are adult females with their young sons and daughters. | 0:39:31 | 0:39:36 | |

And this is how they spend most of their time, | 0:39:36 | 0:39:39 | |

lounging on the ground, grooming one another. | 0:39:39 | 0:39:42 | |

The male is an enormously powerful creature, | 0:39:59 | 0:40:02 | |

but he only uses his strength... | 0:40:02 | 0:40:06 | |

when he is actually protecting his own family | 0:40:06 | 0:40:10 | |

from a marauding male from another group. | 0:40:10 | 0:40:12 | |

And it's very, very rare | 0:40:15 | 0:40:17 | |

that there is any violence within the group. | 0:40:17 | 0:40:21 | |

So it seems really very unfair | 0:40:24 | 0:40:26 | |

that man should have chosen the gorilla | 0:40:26 | 0:40:29 | |

to symbolise all that is aggressive and violent | 0:40:29 | 0:40:34 | |

when that's the one thing the gorilla is not, and that we are. | 0:40:34 | 0:40:38 | |

That grasping, manipulative hand has now become something more, | 0:40:50 | 0:40:54 | |

an instrument with which to explore and investigate. | 0:40:54 | 0:40:59 | |

The fingers can delicately revolve a small object | 0:40:59 | 0:41:02 | |

and investigate it from every angle. | 0:41:02 | 0:41:04 | |

They can feel not only its shape, but its texture, | 0:41:04 | 0:41:07 | |

for the fingers, since they're no longer required | 0:41:07 | 0:41:09 | |

to be put flat on the ground in support of the body, | 0:41:09 | 0:41:12 | |

have sensitive pads at the end, | 0:41:12 | 0:41:14 | |

covered with tiny ridges of skin to enhance the sense of touch. | 0:41:14 | 0:41:18 | |

Every gorilla, in fact, | 0:41:18 | 0:41:20 | |

has its own unique fingerprints, just as we have. | 0:41:20 | 0:41:23 | |

The gorilla family spends its day gently grazing, | 0:41:38 | 0:41:42 | |

and there's plenty of time for play. | 0:41:42 | 0:41:44 | |

Half-grown blackback males regularly have wrestling matches. | 0:42:04 | 0:42:09 | |

Sometimes they even allow others to join in. | 0:43:11 | 0:43:15 | |

Though they may play games, | 0:43:50 | 0:43:52 | |

you don't forget that these are the rulers of the forest, | 0:43:52 | 0:43:56 | |

and the great silverback is king of the whole group. | 0:43:56 | 0:43:59 | |

He's so enormously strong that he need fear nothing | 0:43:59 | 0:44:03 | |

except a man armed with a spear or a gun. | 0:44:03 | 0:44:06 | |

No enemies and an unlimited supply of food | 0:44:10 | 0:44:13 | |

that can be gathered by stretching out an arm, | 0:44:13 | 0:44:15 | |

the gorilla has no need to remain particularly agile | 0:44:15 | 0:44:19 | |

in either body or mind. | 0:44:19 | 0:44:21 | |

APES MAKE ALARM CALLS | 0:44:25 | 0:44:28 | |

There is one other ape living in these forests. | 0:44:36 | 0:44:38 | |

Whereas a gorilla lives on, perhaps, | 0:44:43 | 0:44:45 | |

a couple of dozen different kinds of plants, | 0:44:45 | 0:44:48 | |

this ape eats the leaves of over 200. | 0:44:48 | 0:44:53 | |

And it not only eats leaves, it eats bark, blossoms, fruit, | 0:44:53 | 0:44:58 | |

and, as well as that, termites and ants and honey, | 0:44:58 | 0:45:04 | |

birds' eggs, birds, and even the flesh of small mammals. | 0:45:04 | 0:45:08 | |

And in order to do that, | 0:45:08 | 0:45:09 | |

you need a very nimble mind, an inquisitive disposition, | 0:45:09 | 0:45:14 | |

and that is exactly what these chimpanzees have got. | 0:45:14 | 0:45:19 | |

Chimps spend a considerable amount of time on the ground, | 0:45:33 | 0:45:36 | |

but they've not become so adapted to it as the gorilla. | 0:45:36 | 0:45:39 | |

The gorilla's foot has lost much of its grasp. | 0:45:39 | 0:45:42 | |

A chimp's is still almost as dexterous as its hand. | 0:45:44 | 0:45:48 | |

They're still small enough to go up into the trees | 0:45:57 | 0:45:59 | |

to gather fruit and leaves, | 0:45:59 | 0:46:01 | |

and they also spend the night up there, where it's safer. | 0:46:01 | 0:46:04 | |

Every evening, they make a bed for themselves - | 0:46:11 | 0:46:14 | |

a springy platform constructed by bending over the ends of branches. | 0:46:14 | 0:46:18 | |

They live in large groups, sometimes up to 50 strong. | 0:46:38 | 0:46:42 | |

And they need to recognise one another as individuals. | 0:46:42 | 0:46:45 | |

Lemurs do this by making distinctive scent marks. | 0:46:45 | 0:46:49 | |

Chimps, with less sensitive noses, do it by sight. | 0:46:49 | 0:46:53 | |

So, like us, they have very different and immediately recognisable faces. | 0:46:53 | 0:46:58 | |

The most abiding relationships within the group | 0:47:09 | 0:47:12 | |

are between mother and young. | 0:47:12 | 0:47:14 | |

A baby will remain clinging to its mother, or close by her, | 0:47:14 | 0:47:17 | |

for at least five years. | 0:47:17 | 0:47:19 | |

So the wisdom and experience of the community, its culture, | 0:47:19 | 0:47:24 | |

is passed on this way from one generation to another. | 0:47:24 | 0:47:27 | |

The skills of motherhood, for example, | 0:47:27 | 0:47:29 | |

are learned by a daughter watching her mother handling a new baby. | 0:47:29 | 0:47:34 | |

So if a young female chimp is taken into captivity | 0:47:34 | 0:47:37 | |

and deprived of that experience, | 0:47:37 | 0:47:39 | |

she will not know how to suckle her own babe and has to be shown. | 0:47:39 | 0:47:42 | |

Friendships are made and relationships sustained | 0:47:48 | 0:47:51 | |

throughout the group by grooming. | 0:47:51 | 0:47:53 | |

What started as a simple act of toilet | 0:47:53 | 0:47:56 | |

has now become the most potent form of social bonding within the group. | 0:47:56 | 0:48:00 | |

Every individual seems to enjoy it enormously. | 0:48:02 | 0:48:05 | |

An adult returning to the group after having strayed away for some days | 0:48:05 | 0:48:09 | |

is greeted with an ecstatic bout of grooming by friends. | 0:48:09 | 0:48:13 | |

Grooming like this has been a crucial influence | 0:48:22 | 0:48:25 | |

in the development of chimp behaviour. | 0:48:25 | 0:48:27 | |

It starts when the newly-born babe is cleaned by its mother. | 0:48:27 | 0:48:31 | |

For several years, the warm body of the mother | 0:48:31 | 0:48:33 | |

represents comfort and security. | 0:48:33 | 0:48:36 | |

And, as he becomes more independent, he runs back to her for that comfort | 0:48:36 | 0:48:40 | |

when things go wrong or he's frightened. | 0:48:40 | 0:48:42 | |

He still gets a similar pleasure when he's full-grown | 0:48:42 | 0:48:45 | |

with these long sessions of grooming, | 0:48:45 | 0:48:47 | |

that may go on for a couple of hours at a time. | 0:48:47 | 0:48:51 | |

A junior group member of the group will present himself for grooming | 0:48:51 | 0:48:54 | |

as an act of submission. | 0:48:54 | 0:48:56 | |

A dominant individual will accept it as a tribute. | 0:48:56 | 0:48:59 | |

Their agile fingers have allowed chimps | 0:49:50 | 0:49:53 | |

to make one further and highly important development. | 0:49:53 | 0:49:56 | |

This youngster is collecting one of his favourite foods, tree termites, | 0:49:58 | 0:50:03 | |

winkling them out of a hole with a stick | 0:50:03 | 0:50:05 | |

that he's specially cut and trimmed for the purpose. | 0:50:05 | 0:50:08 | |

It's a simple tool. | 0:50:08 | 0:50:09 | |

So chimpanzees live rich and varied lives. | 0:50:13 | 0:50:17 | |

They're members of a complex social group | 0:50:17 | 0:50:20 | |

with all the excitements that involves. | 0:50:20 | 0:50:22 | |

THEY CRY OUT | 0:50:22 | 0:50:24 | |

They have the most extensive vocabulary of sounds of any animal, | 0:50:27 | 0:50:30 | |

apart from man. | 0:50:30 | 0:50:31 | |

They make tools, and they have an unquenchable curiosity, | 0:50:31 | 0:50:35 | |

testing everything to find out how it moves, how it bends, | 0:50:35 | 0:50:39 | |

what it feels like, above all, what it tastes like. | 0:50:39 | 0:50:43 | |

This ability, indeed willingness, | 0:50:50 | 0:50:53 | |

to experiment with different kinds of foods | 0:50:53 | 0:50:57 | |

means that chimpanzees can not only live in forests like these, | 0:50:57 | 0:51:02 | |

but can venture out into more open country, into savannahs. | 0:51:02 | 0:51:08 | |

And once there, they can find not only leaves, but meat. | 0:51:08 | 0:51:13 | |

That move into open country was first made about 15 million years ago | 0:51:13 | 0:51:19 | |

by another primate, one of the very early ones. | 0:51:19 | 0:51:23 | |

It found, when it got there, that the very talents | 0:51:23 | 0:51:26 | |

that it had developed in the forest for moving around in the trees | 0:51:26 | 0:51:30 | |

were very useful out on the plains. | 0:51:30 | 0:51:33 | |

The stereoscopic eyes, which enabled it to see game in the far distance, | 0:51:33 | 0:51:39 | |

the manipulative hands, | 0:51:39 | 0:51:40 | |

which enabled it to use not just tools, but weapons. | 0:51:40 | 0:51:45 | |

In fact, it became a hunter, | 0:51:45 | 0:51:47 | |

and that early primate was man's ancestor. | 0:51:47 | 0:51:50 | |

Chimps are rather conservative cousins, | 0:51:53 | 0:51:56 | |

removed by about 15 million years. | 0:51:56 | 0:52:00 | |

Nonetheless, we both share many characteristics | 0:52:00 | 0:52:03 | |

in our bodies and behaviour, | 0:52:03 | 0:52:05 | |

that are the common inheritance from the ancient creatures | 0:52:05 | 0:52:08 | |

that once spent all their lives in the trees. | 0:52:08 | 0:52:11 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:53:57 | 0:54:00 |