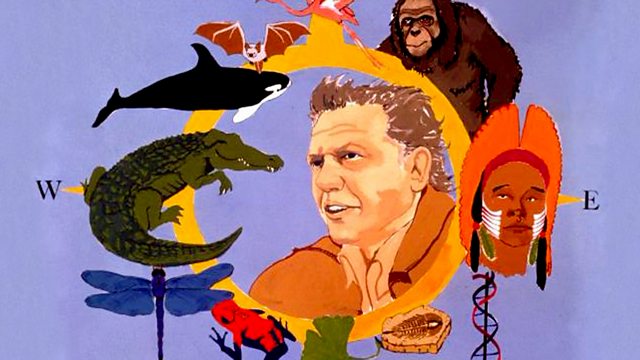

Conquest of the Waters Life on Earth

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Conquest of the Waters. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Life began in the sea. | 0:00:33 | 0:00:35 | |

The water carries oxygen so that creatures can breathe, | 0:00:35 | 0:00:38 | |

and microscopic organisms to provide them with food. | 0:00:38 | 0:00:42 | |

It's a rich world, it covers three quarters of the planet, | 0:00:42 | 0:00:45 | |

and the fish are masters of it. | 0:00:45 | 0:00:48 | |

The world of water is a varied one. | 0:00:55 | 0:00:57 | |

But the fish, by developing into thousands of different forms, | 0:00:57 | 0:01:01 | |

exploit almost every part of it. | 0:01:01 | 0:01:04 | |

Collecting different food requires different-shaped bodies. | 0:01:04 | 0:01:08 | |

And some are quite unexpected. | 0:01:08 | 0:01:11 | |

They've developed a multitude of different ways of propelling themselves through the water. | 0:01:35 | 0:01:41 | |

In size, they vary enormously. | 0:02:13 | 0:02:16 | |

There are giants. | 0:02:16 | 0:02:17 | |

A grouper like this can grow to be twice as long as a man. | 0:02:17 | 0:02:20 | |

Others are so tiny that they can slip inside a big fish's mouth and pick its teeth for it. | 0:02:20 | 0:02:27 | |

Fish have developed some surprising ways of finding their way about | 0:02:36 | 0:02:41 | |

in this varied underwater world. | 0:02:41 | 0:02:43 | |

The four-eyed fish has eyes divided horizontally | 0:02:44 | 0:02:46 | |

so that it can look above the surface and below it at the same time. | 0:02:46 | 0:02:52 | |

On the other hand, the cave fish, | 0:02:52 | 0:02:54 | |

which normally lives in eternal blackness, has no eyes at all. | 0:02:54 | 0:02:57 | |

How did this astounding variety come about? | 0:03:00 | 0:03:04 | |

What were the earliest fishes like, | 0:03:04 | 0:03:05 | |

whose descendents now exploit the resources | 0:03:05 | 0:03:08 | |

of the seas, lakes and rivers in such a multitude of different ways? | 0:03:08 | 0:03:12 | |

The answer may lie with one of the simplest organisms in the sea. | 0:03:12 | 0:03:17 | |

It's a tiny, insignificant little blob of jelly. | 0:03:30 | 0:03:35 | |

And amazing, indeed, fantastic though it is, | 0:03:35 | 0:03:39 | |

there are good reasons to suppose that it was a creature like this | 0:03:39 | 0:03:45 | |

that gave rise to a line which led not only to the fish, | 0:03:45 | 0:03:48 | |

but through them to the amphibians, reptiles, mammals and man. | 0:03:48 | 0:03:53 | |

It's called, not very attractively but quite accurately, a sea squirt. | 0:03:53 | 0:03:58 | |

And to know why, we have to look at it in water. | 0:03:58 | 0:04:02 | |

Its structure is very simple indeed. | 0:04:06 | 0:04:08 | |

Just a U-shaped tube enclosed in jelly. | 0:04:08 | 0:04:11 | |

It sucks water in at the top, | 0:04:12 | 0:04:14 | |

passes it through a grid inside the body | 0:04:14 | 0:04:17 | |

that filters out the food particles, | 0:04:17 | 0:04:19 | |

and then squirts it out at the side. | 0:04:19 | 0:04:22 | |

When it first hatches, however, it's rather different. | 0:04:23 | 0:04:27 | |

And here is the clue that links it to fish. | 0:04:27 | 0:04:29 | |

It has a tail with a thin, flexible rod in it. | 0:04:29 | 0:04:32 | |

Little bunches of muscle are attached to the rod | 0:04:32 | 0:04:35 | |

so that the animal can swim | 0:04:35 | 0:04:37 | |

by beating it from side to side. | 0:04:37 | 0:04:39 | |

In front, it has some sensory pits, | 0:04:41 | 0:04:43 | |

so it has some perception of its surroundings. | 0:04:43 | 0:04:47 | |

We know that this is a very ancient body pattern. | 0:04:47 | 0:04:49 | |

A fossil creature with both these characters has been found in rocks 530 million years old. | 0:04:49 | 0:04:55 | |

Here again, those bunches of muscles attached to a rod. | 0:04:55 | 0:05:00 | |

It's larger, but built on the same principles as the young sea squirt. | 0:05:00 | 0:05:04 | |

And a creature very like this still survives today - the lancelet. | 0:05:04 | 0:05:09 | |

This tiny sliver of flesh has no jaws, | 0:05:15 | 0:05:17 | |

just a mouth surrounded by tentacles. | 0:05:17 | 0:05:20 | |

The bunches of muscles attached to the rod in its back | 0:05:20 | 0:05:23 | |

enable it to swim with an S-shaped wriggle, | 0:05:23 | 0:05:26 | |

each bend pushing against the water so the creature moves forward. | 0:05:26 | 0:05:30 | |

Here it's filmed in slow motion. | 0:05:30 | 0:05:32 | |

It's an action that's going to appear again and again in what is to come. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:38 | |

Lancelets live half-buried in the bottom of the sea | 0:05:38 | 0:05:41 | |

with just their heads projecting above the gravel, | 0:05:41 | 0:05:43 | |

so that they can filter-feed. | 0:05:43 | 0:05:46 | |

Another creature has the same kind of lifestyle | 0:05:52 | 0:05:55 | |

and is built on similar lines, and it swims in the same way as the lancelet. | 0:05:55 | 0:06:00 | |

It's a lamprey. | 0:06:03 | 0:06:05 | |

And later, in some species, it will change from filter-feeding to a parasitic way of life, | 0:06:05 | 0:06:11 | |

using a rasping sucker at its head end. | 0:06:11 | 0:06:13 | |

It extracts oxygen from the water, | 0:06:14 | 0:06:16 | |

and continues to suck it in at the mouth and expel it through gill slits on the neck. | 0:06:16 | 0:06:21 | |

Its close relative, the hagfish, lives in the sea, | 0:06:23 | 0:06:26 | |

sometimes burying itself in the mud, | 0:06:26 | 0:06:28 | |

sometimes fastening itself to fish with its teeth and eating with a sucker-like mouth. | 0:06:28 | 0:06:34 | |

So, and judging from the design of their bodies and the way they move them, | 0:06:36 | 0:06:40 | |

there does seem to be a connection between the young sea squirt, the lancelet | 0:06:40 | 0:06:44 | |

and the hagfish and the lamprey. | 0:06:44 | 0:06:47 | |

But although the hagfish looks like a fish, it's not one. | 0:06:47 | 0:06:51 | |

It has no strengthening to that rod in the back, | 0:06:51 | 0:06:54 | |

no real backbone and no jaws. | 0:06:54 | 0:06:57 | |

Of course, it could be that the reason that the lamprey and the hagfish haven't got any jaws | 0:07:02 | 0:07:07 | |

is not that they are primitive creatures that never developed them, | 0:07:07 | 0:07:11 | |

but they are degenerate ones that lost them. | 0:07:11 | 0:07:15 | |

The way to find the answer to that is to look in the rocks. | 0:07:15 | 0:07:19 | |

The earliest fossils of shells and corals appear about 600 million years ago. | 0:07:19 | 0:07:25 | |

And then, for 200 million years, there's no sign whatever of any backboned animals. | 0:07:25 | 0:07:31 | |

But then, suddenly, they appear. | 0:07:31 | 0:07:33 | |

Some of the finest specimens have been found in these ancient rocks | 0:07:33 | 0:07:37 | |

at the mouth of the Severn, in the west of England. | 0:07:37 | 0:07:40 | |

And these creatures have no jaws either. | 0:07:42 | 0:07:44 | |

They have scales down their flanks and a head covered by a heavy bony shield. | 0:07:44 | 0:07:49 | |

They must have swum by wriggling this body | 0:07:49 | 0:07:52 | |

and pushing their head along the bottom. | 0:07:52 | 0:07:55 | |

And at the front, between two small eyes, there is a nostril. | 0:07:55 | 0:07:58 | |

In fact, it's a kind of lamprey in armour. | 0:07:58 | 0:08:02 | |

At the time of which we are talking, about 400 million years ago, | 0:08:05 | 0:08:09 | |

the face of the Earth was not at all like what it is today. | 0:08:09 | 0:08:13 | |

The relationships of the continents, the ocean basins, the coastlines, all were very different. | 0:08:13 | 0:08:17 | |

Only in a few places can you today get a clear picture of what those ancient shores were like. | 0:08:17 | 0:08:23 | |

And here, in Western Australia, in the Kimberly Ranges, | 0:08:23 | 0:08:26 | |

there's one of them. | 0:08:26 | 0:08:27 | |

And the best place to see it is from the air. | 0:08:27 | 0:08:31 | |

Rising above the parched and sandy scrub, | 0:08:41 | 0:08:44 | |

there are strangely shaped outcrops of rock. | 0:08:44 | 0:08:48 | |

Those bluffs owe their curious shape not to the erosion of wind and rain | 0:08:52 | 0:08:56 | |

but to the labours, millions of years ago, of coral polyps. | 0:08:56 | 0:09:01 | |

We are flying over an ancient seabed, | 0:09:08 | 0:09:10 | |

with the original coast and the land behind it, now a rocky plateau, | 0:09:10 | 0:09:15 | |

stretching away in the distance. | 0:09:15 | 0:09:17 | |

Once, this plain was covered by a shallow blue lagoon | 0:09:17 | 0:09:20 | |

in which corals built their great constructions of limestone. | 0:09:20 | 0:09:24 | |

Over the millennia, rivers eroded the continent nearby, | 0:09:24 | 0:09:28 | |

washed down the sand and mud | 0:09:28 | 0:09:29 | |

and deposited it over the sea floor. | 0:09:29 | 0:09:32 | |

So the lagoons slowly silted up and the sea retreated. | 0:09:32 | 0:09:37 | |

Then the continent rose, rain and sun eroded the mudstones | 0:09:37 | 0:09:41 | |

and eventually the coral reefs were exposed once more as cliffs on a sun-baked plain. | 0:09:41 | 0:09:47 | |

And here I am walking on the ancient seabed. | 0:09:56 | 0:10:00 | |

The surface of the sea would have been near the top of those reefs. | 0:10:00 | 0:10:04 | |

So here I would have been about 200 feet down. | 0:10:04 | 0:10:08 | |

And the sediments that lay on the bottom of that ancient sea | 0:10:08 | 0:10:13 | |

are still here, turned into sandstones and mudstones. | 0:10:13 | 0:10:18 | |

And in them are the remains of the creatures | 0:10:18 | 0:10:21 | |

that lived in those seas. | 0:10:21 | 0:10:23 | |

Here is one that I picked up only a few minutes ago. | 0:10:24 | 0:10:27 | |

It's the scale of a huge fish. | 0:10:27 | 0:10:31 | |

And this is the flank of a smaller fish with many scales on it. | 0:10:31 | 0:10:38 | |

And this, which is perhaps the least impressive of all, | 0:10:38 | 0:10:40 | |

is actually the most interesting, because this is a fossil skull. | 0:10:40 | 0:10:45 | |

There is the line of its lower jaw. | 0:10:45 | 0:10:49 | |

And if this nodule is treated with acids, the matrix will be eroded away | 0:10:49 | 0:10:54 | |

and expose the perfectly preserved bones of the skull. | 0:10:54 | 0:10:58 | |

These creatures, 400 million years old, | 0:11:02 | 0:11:04 | |

were a considerable advance on the lancelets and lampreys | 0:11:04 | 0:11:09 | |

because they had true jaws. | 0:11:09 | 0:11:11 | |

And on their edges, the scales grew particularly long and sharp | 0:11:11 | 0:11:14 | |

so that the fish could bite and cut. | 0:11:14 | 0:11:18 | |

Jaws armed with teeth | 0:11:20 | 0:11:23 | |

enabled the fish to become very effective food-gatherers, | 0:11:23 | 0:11:26 | |

and so grow into large and powerful creatures. | 0:11:26 | 0:11:29 | |

And some of them became monsters. | 0:11:29 | 0:11:31 | |

Judging from the size of these gigantic teeth, | 0:11:33 | 0:11:36 | |

the shark was about 45 feet long. | 0:11:36 | 0:11:40 | |

It's extinct, but its relatives are very much alive. | 0:11:40 | 0:11:45 | |

Sensitive pits in the front of the head, nostrils, | 0:12:09 | 0:12:12 | |

enable them to detect their prey from great distances. | 0:12:12 | 0:12:15 | |

The hammerhead shark is said to be particularly sensitive. | 0:12:15 | 0:12:19 | |

And this may explain the grotesque shape of its head. | 0:12:19 | 0:12:23 | |

There's a nostril at the end of each side of the hammer. | 0:12:23 | 0:12:26 | |

And the fish habitually swings its head from side to side. | 0:12:26 | 0:12:30 | |

So when the scent is equally strong in both nostrils, | 0:12:30 | 0:12:33 | |

then it must know that its prey lies straight ahead. | 0:12:33 | 0:12:37 | |

That rod in the back has now been strengthened with cartilage. | 0:12:38 | 0:12:42 | |

And the entire skeleton of sharks is built from this soft, light material. | 0:12:42 | 0:12:47 | |

They still swim like the lancelets, with sideways beats of their body | 0:12:49 | 0:12:52 | |

which are restricted mostly to the back half and to the tail. | 0:12:52 | 0:12:57 | |

The thrust created tends to drive the nose downwards, | 0:12:57 | 0:13:00 | |

and to compensate for that, sharks have a pair of horizontal fins on either side at the front, | 0:13:00 | 0:13:05 | |

like the vanes of a submarine. | 0:13:05 | 0:13:07 | |

But these fins are stiff and inflexible. | 0:13:07 | 0:13:11 | |

The shark can't twist them vertically to act as brakes. | 0:13:11 | 0:13:14 | |

Indeed, a charging shark can't stop, only swerve to one side. | 0:13:14 | 0:13:18 | |

Nor can it swim backwards. | 0:13:18 | 0:13:20 | |

Furthermore, since its body is heavier than water, if it stopped swimming, a shark would sink. | 0:13:20 | 0:13:27 | |

The wobbegong, a shark from Australian waters, | 0:13:32 | 0:13:35 | |

has a tendency to do just that. | 0:13:35 | 0:13:38 | |

It's largely abandoned the effort of perpetually swimming | 0:13:38 | 0:13:42 | |

to keep in mid-water, | 0:13:42 | 0:13:43 | |

and has settled on the sea floor where it leads a more restful life. | 0:13:43 | 0:13:48 | |

The transition from continuous swimming in the open sea | 0:13:56 | 0:14:00 | |

to a life more or less permanently on the bottom | 0:14:00 | 0:14:03 | |

can be seen in a series of fishes. | 0:14:03 | 0:14:05 | |

The dogfish is very shark-like. | 0:14:08 | 0:14:10 | |

The angel shark is rather more flattened, | 0:14:12 | 0:14:15 | |

with wide side fins and a rather smaller tail. | 0:14:15 | 0:14:18 | |

The ray has flattened its body to an extreme degree, | 0:14:24 | 0:14:27 | |

dispensing with that rear engine, the powerful thrashing tail, | 0:14:27 | 0:14:31 | |

and expanding the lateral fins | 0:14:31 | 0:14:33 | |

so their ripples can take over the job of propelling the fish through the water. | 0:14:33 | 0:14:38 | |

And it spends most of its time lying on the bottom. | 0:14:38 | 0:14:42 | |

A light dusting of gravel does wonders for camouflage. | 0:14:56 | 0:15:01 | |

The sawfish shark is another bottom-liver. | 0:15:06 | 0:15:09 | |

It uses its extraordinary blade like a double-edged scythe, | 0:15:09 | 0:15:13 | |

excavating in the sand and gravel for shells and crabs | 0:15:13 | 0:15:17 | |

and sometimes flailing through a shoal of fish, | 0:15:17 | 0:15:19 | |

slashing them so that they fall injured and can be eaten. | 0:15:19 | 0:15:23 | |

So, bodies with cartilaginous skeletons | 0:15:25 | 0:15:28 | |

developed into two main shapes. | 0:15:28 | 0:15:30 | |

Long ones, like sharks, | 0:15:30 | 0:15:32 | |

and wide ones, like rays and skates. | 0:15:32 | 0:15:36 | |

But having learned, as it were, to live on the bottom, | 0:15:51 | 0:15:55 | |

some rays took off again. | 0:15:55 | 0:15:57 | |

Undulating side fins are effective motors for mid-water swimming, | 0:15:57 | 0:16:01 | |

provided that speed is not needed. | 0:16:01 | 0:16:04 | |

So they are suitable for fish like the manta ray | 0:16:04 | 0:16:07 | |

that drifts through these surface waters, filter-feeding on plankton. | 0:16:07 | 0:16:12 | |

The blades on either side of the manta's head help to channel the food-bearing water | 0:16:12 | 0:16:16 | |

into the slot-like mouth. | 0:16:16 | 0:16:19 | |

The manta cannot swim much faster than this, | 0:16:19 | 0:16:22 | |

but it wouldn't help its feeding even if it did. | 0:16:22 | 0:16:25 | |

For the water can't flow through the sieve in the gill slits | 0:16:25 | 0:16:28 | |

any faster than it's doing now. | 0:16:28 | 0:16:31 | |

Filter-feeding in the surface of the ocean is clearly a very effective way of life. | 0:16:40 | 0:16:45 | |

It doesn't require much energy, there's an unlimited supply of food, | 0:16:45 | 0:16:49 | |

and some of the fish that have taken to it have become very large indeed. | 0:16:49 | 0:16:53 | |

The basking shark grows to a length of 15 metres - 45 feet. | 0:16:53 | 0:16:59 | |

Only one fish today is any bigger - the whale shark. | 0:16:59 | 0:17:03 | |

And that too is a filter-feeder. | 0:17:03 | 0:17:05 | |

And there, clinging under its tail, is a primitive jawless lamprey, | 0:17:12 | 0:17:16 | |

sucking at its flesh, a reminder of the fish's remote past. | 0:17:16 | 0:17:21 | |

A close relative of the earliest swimmers. | 0:17:21 | 0:17:24 | |

Another filter-feeder - the paddlefish. | 0:17:28 | 0:17:31 | |

But this is only very distantly related to the sharks and rays. | 0:17:31 | 0:17:35 | |

400 million years ago, right at the beginning of fish history, | 0:17:36 | 0:17:39 | |

a group started constructing their skeletons not of cartilage but of solid bone. | 0:17:39 | 0:17:45 | |

And the ancestors of the paddlefish were among them. | 0:17:45 | 0:17:50 | |

And another of these primitive bony fish, the sturgeon. | 0:17:50 | 0:17:53 | |

Not only does it have bone in its internal skeleton, | 0:17:53 | 0:17:56 | |

it also has heavy bony scales in its skin. | 0:17:56 | 0:18:00 | |

It's the eggs of this fish that are made into caviar. | 0:18:17 | 0:18:21 | |

It still swims very like a shark, | 0:18:28 | 0:18:30 | |

with sweeps of its hind body and tail. | 0:18:30 | 0:18:33 | |

And the tail looks shark-like too. | 0:18:33 | 0:18:37 | |

Soon after the bony fish first appeared, | 0:18:41 | 0:18:43 | |

they spread from the seas up the rivers to colonise the fresh waters of the world. | 0:18:43 | 0:18:49 | |

It was an invasion that was to have revolutionary consequences. | 0:18:49 | 0:18:54 | |

The waters of rivers and lakes are shallow compared to the sea, | 0:18:59 | 0:19:03 | |

and often, as a consequence, they get quite warm. | 0:19:03 | 0:19:06 | |

And the warmer water becomes, | 0:19:06 | 0:19:08 | |

the less oxygen it can hold dissolved in it. | 0:19:08 | 0:19:11 | |

That presents a serious problem to any fish living there. | 0:19:11 | 0:19:15 | |

How are they to breathe? | 0:19:15 | 0:19:17 | |

This is one of them, the polypterus. And this is its solution. | 0:19:17 | 0:19:22 | |

It gulps air and then absorbs the gaseous oxygen from a pouch that leads off its gut. | 0:19:23 | 0:19:29 | |

In other words, it has developed a very simple lung. | 0:19:29 | 0:19:32 | |

But an air-filled pouch within the body brings another incidental advantage. | 0:19:33 | 0:19:38 | |

It gives buoyancy. So the bony fish acquired a swim bladder. | 0:19:38 | 0:19:42 | |

A controllable bag of air inside the body. | 0:19:42 | 0:19:46 | |

Now the elements of the modern fish have been assembled. | 0:19:50 | 0:19:53 | |

A swim bladder for buoyancy, | 0:19:53 | 0:19:55 | |

a backbone with muscles attached for strength, | 0:19:55 | 0:19:58 | |

and gills for breathing. | 0:19:58 | 0:20:01 | |

And for further precision and control, there is the lateral line, | 0:20:01 | 0:20:04 | |

a row of tiny pits that are sensitive to pressures and currents in the water. | 0:20:04 | 0:20:08 | |

And so the modern bony fish, like this trout, | 0:20:08 | 0:20:12 | |

is very finely tuned to its world. | 0:20:12 | 0:20:14 | |

This perfection of senses and control of movement | 0:20:23 | 0:20:27 | |

is critical when a pike is on the hunt for roach. | 0:20:27 | 0:20:30 | |

With buoyancy provided by the swim bladder, | 0:20:43 | 0:20:46 | |

the fins can be used entirely for fine adjustments of its position as it hovers. | 0:20:46 | 0:20:52 | |

At normal speed, it's almost impossible to see what happens, it's so fast. | 0:21:47 | 0:21:52 | |

Slowed down, it's possible to see | 0:22:00 | 0:22:02 | |

the enormous acceleration and accuracy. | 0:22:02 | 0:22:04 | |

The actual bite only lasts a split second. | 0:22:04 | 0:22:07 | |

And the prey goes straight in. | 0:22:07 | 0:22:09 | |

I'm standing on the brink of one of the most densely populated parts of the sea. | 0:22:29 | 0:22:34 | |

I'm on the edge of a coral reef at a low tide. | 0:22:34 | 0:22:38 | |

A few feet out there, the bottom sinks dramatically, | 0:22:38 | 0:22:41 | |

and there you will find an abundance of life of all kinds. | 0:22:41 | 0:22:45 | |

Microscopic plants, invertebrates, corals, and, of course, a multitude of fish | 0:22:45 | 0:22:51 | |

that come there to harvest this rich source of food. | 0:22:51 | 0:22:55 | |

Each kind of fish has its own particular place in this mosaic, its own particular food, | 0:22:55 | 0:23:00 | |

and each has, in consequence, developed its own way of swimming, | 0:23:00 | 0:23:04 | |

its own way of using its fins. | 0:23:04 | 0:23:07 | |

The huge number of fish that swarm on the reef, harvesting the great variety of food it offers, | 0:23:19 | 0:23:25 | |

causes considerable social problems. | 0:23:25 | 0:23:28 | |

Each species has its own particular niche on the reef and is designed accordingly. | 0:23:28 | 0:23:35 | |

Many are slim for slipping through the tangle of coral. | 0:23:35 | 0:23:39 | |

Others, like the cowfish, have a rigid box of bony plates | 0:23:39 | 0:23:43 | |

and can stop dead with precise control from its fins. | 0:23:43 | 0:23:47 | |

The trigger sticks its fin-free front half between coral branches to feed. | 0:23:48 | 0:23:53 | |

The angelfish picks off small morsels from the surface of corals, | 0:23:53 | 0:23:57 | |

once again with perfect control. | 0:23:57 | 0:24:00 | |

And this butterfly fish has elongated jaws | 0:24:05 | 0:24:08 | |

that enable it to probe into narrow crevices | 0:24:08 | 0:24:10 | |

with the accuracy of forceps. | 0:24:10 | 0:24:14 | |

For turning sharply, banking steeply, or simply flapping along, | 0:24:15 | 0:24:19 | |

most coral fishes have been able to abandon the S-shaped wriggle. | 0:24:19 | 0:24:23 | |

They've deployed their fins and adjusted their bodies to live in this particular world. | 0:24:23 | 0:24:28 | |

No shark could do this, but then they are adapted to a different kind of life. | 0:24:39 | 0:24:45 | |

The puffer fish doesn't wriggle its body but it does flex its fins, and to great effect. | 0:24:51 | 0:24:57 | |

The S-shape action is now being used there. | 0:24:57 | 0:25:00 | |

And fins have another important role, as flags. | 0:25:06 | 0:25:09 | |

In such a mixed and dense crowd, it's very much to the advantage of every individual fish | 0:25:09 | 0:25:15 | |

to proclaim its presence and identity from among the throng. | 0:25:15 | 0:25:19 | |

So rivals will be aware that this particular food patch has got an owner. | 0:25:19 | 0:25:24 | |

The same markings will also serve, when the time comes, | 0:25:24 | 0:25:27 | |

to attract a mate of the right species. | 0:25:27 | 0:25:29 | |

The sharks and rays have eyes that, though they see shapes, are largely blind to colour. | 0:25:33 | 0:25:39 | |

It's hardly surprising that they are largely drab-coloured creatures. | 0:25:39 | 0:25:43 | |

But the bony fish have excellent colour vision. | 0:25:43 | 0:25:47 | |

And so they are able to signal to one another with stripes and spots and blotches, | 0:25:47 | 0:25:51 | |

and in the most wonderful variety of colours. | 0:25:51 | 0:25:54 | |

The coral fish can risk making themselves conspicuous | 0:25:55 | 0:25:58 | |

because the reef is full of crevices and corners | 0:25:58 | 0:26:01 | |

where they can dart to safety if danger threatens. | 0:26:01 | 0:26:04 | |

Away from the reef, however, the sea is a dangerous place. | 0:26:11 | 0:26:15 | |

For there, there is nowhere to hide, except among your fellows. | 0:26:15 | 0:26:19 | |

And these are designed for a very different way of life. | 0:26:25 | 0:26:28 | |

Fast swimming, fast feeding in the open sea with plankton at the base of the food chain. | 0:26:28 | 0:26:34 | |

And it's that wriggling body action that pushes them along. | 0:26:34 | 0:26:38 | |

Open-water fish often form huge shoals. | 0:26:51 | 0:26:54 | |

And this may be for safety's sake. | 0:26:54 | 0:26:57 | |

The drifting, darting multitudes of fish may tend to baffle and confuse predators. | 0:26:57 | 0:27:02 | |

And if you meet a shark on your own, it'll go for you. | 0:27:02 | 0:27:06 | |

But if you are with others, your chances are much better. | 0:27:06 | 0:27:10 | |

From the plankton to the small fish and on up the food chain to the big fish. | 0:27:20 | 0:27:27 | |

In the open ocean, speed is of great value. | 0:27:27 | 0:27:30 | |

And since water is very dense, 800 times more so than air, | 0:27:30 | 0:27:33 | |

streamlining is of the greatest importance to fish. | 0:27:33 | 0:27:37 | |

Both hunters and the fish they pursue have developed very similar shapes. | 0:27:37 | 0:27:42 | |

Pointed in front and tapering to a two-bladed symmetrical tail at the back. | 0:27:42 | 0:27:46 | |

Barracuda. Among the most voracious and swift of the bony fish. | 0:27:46 | 0:27:51 | |

And this is a hunter's-eye view | 0:27:57 | 0:27:59 | |

of a fish that escapes not by swimming fast, | 0:27:59 | 0:28:01 | |

but in a quite different way. | 0:28:01 | 0:28:04 | |

It's a flying fish. Its front pair of fins are greatly enlarged so that with a flick of its tail, | 0:28:06 | 0:28:12 | |

it launches itself into the air and out of the hunter's sight. | 0:28:12 | 0:28:16 | |

This is the flight in slow motion. | 0:28:23 | 0:28:25 | |

The fish is already swimming fast when it comes to the surface, | 0:28:25 | 0:28:29 | |

and it takes off, helped by the beating tail which has a specially enlarged lower lobe. | 0:28:29 | 0:28:34 | |

The front fins are then spread to assist the glide. | 0:28:34 | 0:28:38 | |

Occasionally they dip their tails into the surface to give themselves an additional boost. | 0:28:40 | 0:28:45 | |

And so they can sometimes fly for several hundred metres. | 0:28:45 | 0:28:50 | |

Some fish have sought safety by going not upwards but downwards. | 0:28:53 | 0:28:57 | |

These eggs, that float in astronomic numbers on the surface of the sea during the summer, | 0:28:57 | 0:29:02 | |

have come from one of the bottom dwellers. | 0:29:02 | 0:29:05 | |

Only one in 100,000 will survive. | 0:29:05 | 0:29:08 | |

But those that do will pass through a most extraordinary transformation | 0:29:08 | 0:29:12 | |

before they become adult. | 0:29:12 | 0:29:14 | |

After about a week, they hatch into what looks like a fairly normal kind of fish fry. | 0:29:18 | 0:29:24 | |

They hang near the surface where it's warm and there's a lot of oxygen, | 0:29:24 | 0:29:28 | |

feeding on micro-organisms. | 0:29:28 | 0:29:30 | |

Each is not much bigger than a pinhead. | 0:29:30 | 0:29:33 | |

Each one still contains a tiny bag of yolk that will sustain it for a day or two more. | 0:29:46 | 0:29:52 | |

The young fish has eyes on either side of its head, | 0:29:54 | 0:29:57 | |

but they won't remain that way for long. | 0:29:57 | 0:29:59 | |

Its body deepens as it begins to feed, and its stomach swells. | 0:29:59 | 0:30:03 | |

And it develops a swim bladder. | 0:30:03 | 0:30:06 | |

Its eyes are beginning to look a little lopsided. | 0:30:11 | 0:30:14 | |

One is higher than the other. | 0:30:14 | 0:30:17 | |

Now they've developed pigment, but only on one flank, | 0:30:20 | 0:30:24 | |

and they swim on their sides with that coloured flank upwards. | 0:30:24 | 0:30:27 | |

These are going to be flatfish. | 0:30:27 | 0:30:30 | |

Turbot, plaice, sole and flounder also go through such a transformation. | 0:30:30 | 0:30:35 | |

And they finally settle on the bottom. | 0:30:39 | 0:30:41 | |

One eye is now on the edge of the fish. | 0:30:46 | 0:30:50 | |

Now the transformation is complete | 0:30:53 | 0:30:55 | |

and the fish has lost that swim bladder, | 0:30:55 | 0:30:58 | |

for buoyancy is a positive hindrance on the sea bottom. | 0:30:58 | 0:31:02 | |

A bony fish has joined the skates and the rays on the sea floor | 0:31:02 | 0:31:06 | |

by the simple if drastic expedient of lying on its side | 0:31:06 | 0:31:10 | |

and moving one eye right round its body. | 0:31:10 | 0:31:13 | |

Many other bony fish have abandoned the swim bladder and settled down. | 0:31:16 | 0:31:20 | |

Each has found its own way of adapting to life where skill in swimming is less important | 0:31:20 | 0:31:25 | |

than an ability to merge into the background of the sea floor. | 0:31:25 | 0:31:29 | |

So fins can be used for all kinds of other purposes. | 0:31:29 | 0:31:33 | |

This looks like a rock lying on the bottom, | 0:31:33 | 0:31:37 | |

but it has a gill, an eye and an upturned mouth. | 0:31:37 | 0:31:41 | |

It's a stonefish, a hunter that relies on invisibility to catch its prey unawares. | 0:31:41 | 0:31:47 | |

And its fins are coloured and shaped to help its camouflage. | 0:31:47 | 0:31:52 | |

The angler fish uses its fins not for swimming but for walking. | 0:31:54 | 0:31:59 | |

And the front spine of its dorsal fin is a fishing rod. | 0:31:59 | 0:32:03 | |

With that lure, it attracts unsuspecting creatures within range of its mouth. | 0:32:06 | 0:32:11 | |

The bearded ghoul uses its fins for defence. | 0:32:18 | 0:32:21 | |

Without a membrane between them, | 0:32:21 | 0:32:23 | |

they are no longer of any use as stabilisers when swimming, | 0:32:23 | 0:32:26 | |

and instead they are sharp and tipped with poison. | 0:32:26 | 0:32:30 | |

Very effective protection. | 0:32:30 | 0:32:31 | |

It's just what you need if you are lying on the bottom. | 0:32:31 | 0:32:35 | |

The gurnard uses some of the rays of its front pair of fins | 0:32:41 | 0:32:45 | |

as delicate legs for finding food in the gravel. | 0:32:45 | 0:32:48 | |

Fish like those live in comparatively shallow waters, | 0:33:06 | 0:33:10 | |

100 feet, 30 metres, something like that. | 0:33:10 | 0:33:13 | |

Their world is a heavily inhabited one and also quite a bright one | 0:33:13 | 0:33:18 | |

because the water is shallow enough to receive light from the sun. | 0:33:18 | 0:33:21 | |

It's also one that's comparatively familiar to us. | 0:33:21 | 0:33:25 | |

For one thing, all the sea fish that we eat come from it. | 0:33:25 | 0:33:28 | |

For another, hundreds of thousands of people regularly visit it wearing aqualungs. | 0:33:28 | 0:33:34 | |

But in fact it is only a tiny proportion of the seas of the world. | 0:33:34 | 0:33:40 | |

Most of the oceans are very, very much deeper than that. | 0:33:40 | 0:33:44 | |

And to visit those deep waters, you can't go down in an aqualung, | 0:33:44 | 0:33:48 | |

you have to use something like this - a submersible. | 0:33:48 | 0:33:52 | |

These craft work on the sea floor, helping in the drilling for oil. | 0:34:07 | 0:34:11 | |

They give a splendid view of what's happening at depth, both to oil engineers and to fish watchers. | 0:34:11 | 0:34:17 | |

There's a highly sensitive television camera on the outside of the hull, | 0:34:34 | 0:34:38 | |

with a monitor screen in the cockpit | 0:34:38 | 0:34:41 | |

and spotlights to illuminate places | 0:34:41 | 0:34:43 | |

that the sun's rays have never reached. | 0:34:43 | 0:34:46 | |

As we go down, it gets darker and darker. | 0:34:48 | 0:34:52 | |

And the pressure increases too, very quickly. | 0:34:52 | 0:34:55 | |

By the time we are 500 feet, the loading on this viewing dome here will be about 70 tons. | 0:34:55 | 0:35:03 | |

And it also gets colder and colder. | 0:35:03 | 0:35:07 | |

At one point, and the precise depth varies according to where we are in the world, | 0:35:07 | 0:35:12 | |

between, say, 20 metres, which is about 60 feet, | 0:35:12 | 0:35:15 | |

and 150 metres, 450 feet, | 0:35:15 | 0:35:18 | |

it suddenly gets very much colder indeed and drops to about five degrees above freezing. | 0:35:18 | 0:35:25 | |

That point is called the thermocline, | 0:35:25 | 0:35:28 | |

and it's a kind of frontier in the ocean, | 0:35:28 | 0:35:32 | |

separating two very different worlds between which there is very little traffic. | 0:35:32 | 0:35:36 | |

Above, there is the sunlit, warm waters near the surface which have their own circulation, | 0:35:36 | 0:35:44 | |

and below the thermocline, there's the black, near-freezing world of the ocean depths. | 0:35:44 | 0:35:50 | |

And there, there live very different fish indeed. | 0:35:50 | 0:35:54 | |

This is part of the world that man is only just beginning to explore. | 0:35:59 | 0:36:03 | |

Until a few years ago, most of our knowledge of these creatures | 0:36:03 | 0:36:07 | |

came from specimens hauled up in dredges. | 0:36:07 | 0:36:10 | |

But, as they came up, changes in pressure and temperature | 0:36:10 | 0:36:14 | |

usually distorted their bodies and they quickly died. | 0:36:14 | 0:36:17 | |

Only now, from such craft as the submersibles, are we beginning to get an accurate idea | 0:36:17 | 0:36:23 | |

of what life is really like in the deeper parts of the oceans. | 0:36:23 | 0:36:27 | |

A shark, built on the same pattern as its relatives above. | 0:36:29 | 0:36:33 | |

Like most of the inhabitants of these oxygen-poor waters, | 0:36:33 | 0:36:36 | |

it moves comparatively slowly. | 0:36:36 | 0:36:39 | |

Probably never meeting a boundary or a barrier in the endless deep sea. | 0:36:39 | 0:36:44 | |

A red prawn, doubtless food for some big fish. | 0:36:47 | 0:36:51 | |

An extraordinary relative of the prawn, another crustacean, called an ostracod. | 0:36:59 | 0:37:03 | |

Fossils of species very like these have been found in extremely ancient rocks, | 0:37:03 | 0:37:09 | |

so we know that they were here long before the fish arrived. | 0:37:09 | 0:37:14 | |

This fish still uses that antique way of swimming with S-shaped undulations of its body. | 0:37:14 | 0:37:20 | |

A fangtooth, one of the hunters of this lightless world. | 0:37:31 | 0:37:35 | |

Our knowledge of the fish at these depths is still very fragmentary. | 0:37:36 | 0:37:39 | |

Many species have never been filmed, | 0:37:39 | 0:37:42 | |

and we know them only from a few mangled specimens and still photographs. | 0:37:42 | 0:37:47 | |

This bait on a line is suspended from a rod dangling in front of an upper jaw | 0:37:48 | 0:37:53 | |

lined with needle teeth. | 0:37:53 | 0:37:56 | |

It's another kind of angler fish. | 0:37:56 | 0:37:58 | |

There are so few animals at these depths that when a meal arrives, | 0:38:00 | 0:38:03 | |

a hunter must make quite sure of catching it. | 0:38:03 | 0:38:06 | |

This angler normally looks like this, | 0:38:13 | 0:38:15 | |

but when it's had its meal, its stomach becomes hugely distended. | 0:38:15 | 0:38:20 | |

The gulper is little more than a swimming mouth, | 0:38:21 | 0:38:24 | |

also with a stomach capable of great extension. | 0:38:24 | 0:38:27 | |

The bigger the stomach can go, the wider the choice of prey, | 0:38:27 | 0:38:31 | |

and meals may be few and far between. | 0:38:31 | 0:38:34 | |

Many fish produce lights in this blackness, some as face patches or dots along the sides. | 0:38:36 | 0:38:41 | |

At night, many of them move up to shallower water where, of course, it's still dark. | 0:38:41 | 0:38:48 | |

With special light-sensitive cameras and a little illumination, | 0:38:57 | 0:39:01 | |

you can just make out the fish that are producing these lights. | 0:39:01 | 0:39:04 | |

They are called flashlight fish. | 0:39:04 | 0:39:07 | |

With no illumination at all, they become disembodied green spots again, | 0:39:24 | 0:39:28 | |

mysteriously circulating in the blackness. | 0:39:28 | 0:39:32 | |

The light is produced by bacteria which live in this one patch of skin | 0:39:34 | 0:39:39 | |

and glow as a normal by-product of the chemistry of their life processes. | 0:39:39 | 0:39:43 | |

The light may serve the flashlight fish in several ways. | 0:39:46 | 0:39:49 | |

It may be a sign to other members of the shoal. It may baffle predators. | 0:39:49 | 0:39:53 | |

After a fish switches off its light, it immediately darts away to a different position. | 0:39:53 | 0:39:58 | |

Or it may simply be a method of finding your way around in the blackness. | 0:39:58 | 0:40:03 | |

The problem of finding the way in the dark faces other fish too. | 0:40:13 | 0:40:17 | |

They live in turbid waters and under a thick carpet of floating vegetation. | 0:40:17 | 0:40:22 | |

Not an easy place to find them. | 0:40:22 | 0:40:25 | |

This somewhat surprising piece of apparatus... | 0:40:33 | 0:40:39 | |

is the latest device developed and designed by research workers interested in electric fishes. | 0:40:39 | 0:40:48 | |

This plastic tube has got two leads which come up through this cable | 0:40:48 | 0:40:52 | |

along here to this extraordinary hat. | 0:40:52 | 0:40:56 | |

There, they go into this amplifier, | 0:40:56 | 0:40:59 | |

and on the brim of the hat, there's a loudspeaker here | 0:40:59 | 0:41:03 | |

and, very thoughtfully, a counterweight here, | 0:41:03 | 0:41:07 | |

so that when I put the hat on my head, it doesn't flop over one ear. | 0:41:07 | 0:41:13 | |

And then, if I turn on the amplifier, the speaker is next to my ear, | 0:41:13 | 0:41:18 | |

I have one hand free and the wires will pick up the signals of those electric fishes | 0:41:18 | 0:41:26 | |

and I can hear them as a series of clicks. | 0:41:26 | 0:41:30 | |

LOW HUMMING | 0:41:30 | 0:41:32 | |

The fish produce their electricity | 0:41:42 | 0:41:44 | |

from stacks of plate-shaped shells embedded in jelly | 0:41:44 | 0:41:48 | |

that lie in a column along each flank, like batteries. | 0:41:48 | 0:41:51 | |

Each fish sends out a particular kind of discharge. | 0:41:51 | 0:41:55 | |

And each makes a different sound on the loudspeakers. | 0:41:55 | 0:41:58 | |

So these may be another kind of call sign, | 0:41:58 | 0:42:01 | |

like the Morse code of the flashlight fish, | 0:42:01 | 0:42:03 | |

a way of proclaiming identity. | 0:42:03 | 0:42:07 | |

They also certainly help the fish in navigation. | 0:42:07 | 0:42:10 | |

Each creates in the water around it a weak electric field. | 0:42:11 | 0:42:15 | |

Any other solid object in the water causes a change in that field, | 0:42:15 | 0:42:19 | |

and the fish have special pores, spaced out over their bodies, which detect such alterations. | 0:42:19 | 0:42:26 | |

As a result, they are able to find their away about in total darkness. | 0:42:26 | 0:42:30 | |

And they can swim just as accurately backwards as they can forwards. | 0:42:30 | 0:42:34 | |

HIGH-PITCHED HUMMING | 0:42:36 | 0:42:38 | |

PULSING | 0:42:44 | 0:42:46 | |

Electricity has evolved independently in many fishes. | 0:42:46 | 0:42:49 | |

From South America and Africa, in rivers, lakes and also in the sea. | 0:42:49 | 0:42:54 | |

In some, the tail muscles are used. | 0:42:54 | 0:42:57 | |

Others, the head area and even the eye muscles. | 0:42:57 | 0:43:01 | |

A straight, knife-shaped body is characteristic of all these fish, | 0:43:08 | 0:43:12 | |

and it may be important to keep the body stiff in this position | 0:43:12 | 0:43:16 | |

in order to maintain an accurate output of navigational signals. | 0:43:16 | 0:43:21 | |

And the fins do the manoeuvring. | 0:43:21 | 0:43:24 | |

Some frequently rest, wedged between plant stems. | 0:43:24 | 0:43:27 | |

HARSHER AMPLIFIED TONE | 0:43:34 | 0:43:35 | |

Most of the discharges produced by those electric fish | 0:44:03 | 0:44:06 | |

are extremely weak. | 0:44:06 | 0:44:07 | |

You couldn't possibly detect them without special amplifying equipment. | 0:44:07 | 0:44:11 | |

But that is very much not the case with all of them. | 0:44:11 | 0:44:13 | |

This is the most powerful electric fish of all, | 0:44:14 | 0:44:18 | |

the famous electric eel from South America. | 0:44:18 | 0:44:22 | |

This has two kinds of electricity. | 0:44:22 | 0:44:24 | |

Not only does it have batteries which produce the discharges used for navigation, | 0:44:24 | 0:44:29 | |

but it's also capable of delivering a massive electric shock, | 0:44:29 | 0:44:33 | |

which it stuns its prey with and which is quite sufficient to throw me on my back, | 0:44:33 | 0:44:39 | |

if I were not wearing rubber gloves. | 0:44:39 | 0:44:43 | |

And I can demonstrate that electric shock | 0:44:43 | 0:44:47 | |

by tapping him near his head and tail | 0:44:47 | 0:44:49 | |

with these electrodes, which will then, if he gives a shock, | 0:44:49 | 0:44:53 | |

light up these bulbs. | 0:44:53 | 0:44:55 | |

And the more powerful the shock, the more bulbs he will light. | 0:44:55 | 0:44:59 | |

There's a rapid output of volts, | 0:45:02 | 0:45:04 | |

peaking in this case at about 400. Four bulbs were lit. | 0:45:04 | 0:45:08 | |

Of all backboned animals, fish are the only ones to produce electricity in their bodies. | 0:45:08 | 0:45:14 | |

So the bony fish, one way or another, have managed to colonise all the waters of the world, | 0:45:18 | 0:45:23 | |

from the black depths of the sea to inland rivers and lakes, even lakes like this. | 0:45:23 | 0:45:29 | |

Lake Magadi in the Rift Valley of East Africa | 0:45:29 | 0:45:32 | |

is, I think, just about the most hostile environment that I know for land animals, let alone fish. | 0:45:32 | 0:45:39 | |

It's a lake not of water but of solid soda and potash, | 0:45:52 | 0:45:56 | |

solidified by the baking African sun | 0:45:56 | 0:45:58 | |

from solutions bubbling up from volcanic rocks far below. | 0:45:58 | 0:46:02 | |

And here, at last, is somewhere you might think you'll get a place to cool your feet. | 0:46:04 | 0:46:11 | |

You might get a nice refreshing drink of clear, cool water. | 0:46:11 | 0:46:17 | |

And yet in fact... | 0:46:17 | 0:46:19 | |

this water is so...hot that actually it's really quite difficult to bear. | 0:46:19 | 0:46:27 | |

And when you taste it, the water is sickeningly salty. | 0:46:27 | 0:46:32 | |

This is actually one of the hot volcanic springs | 0:46:32 | 0:46:35 | |

where water bubbles up from deep below the surface of the ground, | 0:46:35 | 0:46:40 | |

bringing up a solution of soda and salt to trickle down and crystallise out in the lakes. | 0:46:40 | 0:46:47 | |

You could hardly imagine a less likely place to find a fish. | 0:46:47 | 0:46:53 | |

And yet there it is. A species of tilapia. | 0:46:59 | 0:47:03 | |

The water here can be as high as 43 degrees centigrade, | 0:47:03 | 0:47:07 | |

110 degrees Fahrenheit. | 0:47:07 | 0:47:09 | |

Algae grow here and the fish survive by feeding on it. | 0:47:09 | 0:47:14 | |

Yet another niche, a most unlikely one, | 0:47:14 | 0:47:17 | |

has been filled by the incredibly adaptable fishes. | 0:47:17 | 0:47:21 | |

At the other extreme, there's one fish in the coldest waters on Earth. | 0:47:22 | 0:47:27 | |

Sea water freezes below the temperature of fresh water. | 0:47:34 | 0:47:38 | |

The ice fish from the seas of the Antarctic has developed a substance in its blood | 0:47:38 | 0:47:43 | |

which keeps it liquid even when the sea water above it freezes solid. | 0:47:43 | 0:47:47 | |

It has, in fact, a kind of antifreeze. | 0:47:47 | 0:47:50 | |

But if one wanted to pick out of the 30,000 or so species of fish alive today | 0:47:54 | 0:47:59 | |

the king of them all, my vote would go to this, the salmon. | 0:47:59 | 0:48:03 | |

In the acuteness of its senses, the skilfulness of its navigation, | 0:48:09 | 0:48:13 | |

the strength and athleticism of its body, this surely must be a paragon among fish. | 0:48:13 | 0:48:20 | |

In the Pacific, there are several different kinds. | 0:48:20 | 0:48:22 | |

They spend much of their time in the ocean, feeding on plankton and small fish. | 0:48:22 | 0:48:27 | |

But in the summer, they assemble off the North American coast | 0:48:27 | 0:48:31 | |

and then they begin to battle their way up the rivers. | 0:48:31 | 0:48:34 | |

Even falls don't stop them. | 0:48:35 | 0:48:38 | |

The flexible rod that first appeared in the young sea squirt | 0:48:38 | 0:48:42 | |

is here marvellously muscled and strengthened with a jointed column of bone. | 0:48:42 | 0:48:46 | |

So with a thrash of its hind end and fins, | 0:48:46 | 0:48:50 | |

the movement first developed by the earliest ancestors of the fish, | 0:48:50 | 0:48:54 | |

the salmon can swim and leap up the fastest torrents. | 0:48:54 | 0:48:57 | |

And its lateral line can sense the details of the surge. | 0:48:57 | 0:49:02 | |

The salmon's sense of smell is almost unbelievably acute. | 0:49:16 | 0:49:20 | |

This river is not just any river. | 0:49:20 | 0:49:22 | |

It is the precise one in which all these fish were hatched. | 0:49:22 | 0:49:25 | |

Each has retained a memory of the taste and smell of these waters. | 0:49:25 | 0:49:30 | |

And this has drawn them back across thousands of miles of ocean | 0:49:30 | 0:49:34 | |

so that they may complete their lives where they began them. | 0:49:34 | 0:49:38 | |

During the past few days, | 0:49:48 | 0:49:49 | |

their bodies have been changing with astonishing speed. | 0:49:49 | 0:49:53 | |

These pink salmon have developed a high humped back with thin bodies, | 0:49:53 | 0:49:59 | |

and their lower jaws have become hooked. | 0:49:59 | 0:50:02 | |

The front teeth of the males have developed | 0:50:02 | 0:50:06 | |

into long and powerful fangs. | 0:50:06 | 0:50:09 | |

Hopeless for feeding, | 0:50:09 | 0:50:11 | |

but then the time of feeding is long since over. | 0:50:11 | 0:50:15 | |

Their teeth are for battle. | 0:50:15 | 0:50:18 | |

The males fight for a scrape scooped in the gravel of the river bed. | 0:50:46 | 0:50:51 | |

When one takes possession, a female will join him and lie alongside. | 0:50:51 | 0:50:56 | |

Then, as she sheds her eggs into the gravel, his milt will fertilise them. | 0:50:56 | 0:51:01 | |

And now they're totally spent. | 0:51:37 | 0:51:40 | |

They don't even have enough energy to heal their battered, wounded bodies. | 0:51:40 | 0:51:45 | |

Their scales fall off and the once-powerful muscles, the flesh, dwindles and shrivels. | 0:51:45 | 0:51:52 | |

And they die. All of them. | 0:51:52 | 0:51:55 | |

Not a single one of the millions of fish | 0:51:55 | 0:51:58 | |

which fought their way up this river | 0:51:58 | 0:52:01 | |

ever goes back to the sea. | 0:52:01 | 0:52:03 | |

But their eggs remain, and will stay here throughout the winter, safe in the gravel, | 0:52:03 | 0:52:08 | |

until, in the spring, they'll hatch and the fry will be swept down the river to the ocean. | 0:52:08 | 0:52:15 | |

There they will feed and grow until, at the appointed time, two years hence exactly, | 0:52:15 | 0:52:20 | |

as far as these pink salmon are concerned, the fully-grown fish will once again | 0:52:20 | 0:52:25 | |

beat its way powerfully upriver to the place where it was born. | 0:52:25 | 0:52:29 | |

The salmon is the master both of salt water and fresh, | 0:52:48 | 0:52:52 | |

but one part of the world is closed even to it - the land. | 0:52:52 | 0:52:56 | |

And yet a few fish can survive even there for a short time. | 0:52:56 | 0:53:01 | |

The walking catfish travels over land | 0:53:01 | 0:53:04 | |

using bony fins and a sideways wriggle. | 0:53:04 | 0:53:07 | |

But it's not the first fish to do that. | 0:53:07 | 0:53:09 | |

One managed it some 350 million years ago, and that was a momentous move. | 0:53:09 | 0:53:15 | |

Because from that fish developed frogs and lizards, birds and mammals | 0:53:15 | 0:53:21 | |

and, ultimately, ourselves. | 0:53:21 | 0:53:23 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:53:51 | 0:53:55 |