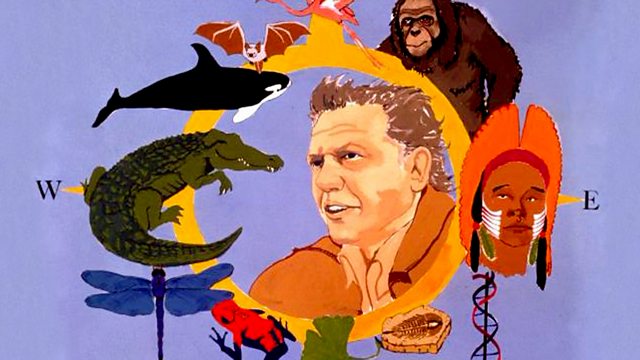

Invasion of the Land Life on Earth

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Invasion of the Land. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

One of the most crucial steps in the story of Life On Earth | 0:00:50 | 0:00:55 | |

happened in a freshwater swamp about 350 million years ago. | 0:00:55 | 0:01:02 | |

The fish began to haul themselves out onto the land. | 0:01:02 | 0:01:05 | |

The land at the time was covered with the first plants. | 0:01:05 | 0:01:09 | |

Very different from these mangrove plants of today, | 0:01:09 | 0:01:12 | |

but nonetheless plants. | 0:01:12 | 0:01:14 | |

In order to get out among them, the fish had to solve two problems. | 0:01:14 | 0:01:18 | |

First, they had the mechanical problem | 0:01:18 | 0:01:21 | |

of hauling themselves onto land, | 0:01:21 | 0:01:23 | |

and second, they had to be able to breathe once they got there. | 0:01:23 | 0:01:27 | |

The way they solved the problem | 0:01:27 | 0:01:29 | |

of hauling themselves up onto the land, | 0:01:29 | 0:01:31 | |

we can see from a small fish | 0:01:31 | 0:01:34 | |

which lives in these mangrove swamps today. | 0:01:34 | 0:01:37 | |

It's in no way closely related to those early fish, | 0:01:37 | 0:01:40 | |

but it does give us an idea of what that scene must have been like. | 0:01:40 | 0:01:44 | |

The mudskipper. | 0:01:44 | 0:01:45 | |

They come up out of the water | 0:01:51 | 0:01:53 | |

to browse on small creatures swarming on the mud. | 0:01:53 | 0:01:57 | |

Their front fins have jointed bones | 0:02:01 | 0:02:04 | |

so the fish can use them as legs to lever itself along. | 0:02:04 | 0:02:09 | |

The mudskipper is not the only fish | 0:02:17 | 0:02:20 | |

to have developed muscular fins like these. | 0:02:20 | 0:02:23 | |

Fossils of one of the first have been found in rocks | 0:02:23 | 0:02:26 | |

laid down just before the time | 0:02:26 | 0:02:28 | |

that backboned animals ventured onto land. | 0:02:28 | 0:02:30 | |

The coelacanth. | 0:02:30 | 0:02:32 | |

Did this extremely ancient fish also use its fins as legs? | 0:02:34 | 0:02:38 | |

Unfortunately, no fossils of them younger than 70 million years | 0:02:38 | 0:02:42 | |

have ever been found, and up to 40 years ago, | 0:02:42 | 0:02:46 | |

scientists concluded that they wouldn't be able to answer | 0:02:46 | 0:02:49 | |

that question for certain as the fish was obviously extinct. | 0:02:49 | 0:02:53 | |

And then, in 1938, a living coelacanth was caught | 0:02:53 | 0:02:57 | |

off the coast of South Africa. | 0:02:57 | 0:03:00 | |

It was the scientific sensation of the century. | 0:03:00 | 0:03:02 | |

Before scientists could get to examine its entrails | 0:03:02 | 0:03:06 | |

and see how they confirmed or denied the deductions they'd made | 0:03:06 | 0:03:10 | |

from the very ancient fossil coelacanths, | 0:03:10 | 0:03:12 | |

the fish was already rotting. | 0:03:12 | 0:03:14 | |

Its guts were thrown away unexamined. | 0:03:14 | 0:03:18 | |

So a huge search was mounted to find another. | 0:03:18 | 0:03:22 | |

Leaflets were printed with pictures of the fish, offering a reward, | 0:03:22 | 0:03:27 | |

and were distributed among the countless fishing villages | 0:03:27 | 0:03:31 | |

off the African coast. | 0:03:31 | 0:03:32 | |

But nothing... until, 14 years later, | 0:03:32 | 0:03:36 | |

a second coelacanth was caught. | 0:03:36 | 0:03:39 | |

It came from a place over 1,000 miles away | 0:03:39 | 0:03:41 | |

from where the first one was landed. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:43 | |

Here in the tiny Comoro Islands, | 0:03:43 | 0:03:47 | |

a small group lying midway between | 0:03:47 | 0:03:49 | |

Madagascar and the coast of East Africa. | 0:03:49 | 0:03:52 | |

The first one, it seems, was a stray. | 0:03:52 | 0:03:55 | |

These waters are the true and only home | 0:03:55 | 0:03:58 | |

of this extraordinary rare fish, | 0:03:58 | 0:04:01 | |

and the people who live in that tiny village | 0:04:01 | 0:04:03 | |

are the world's experts in catching coelacanths. | 0:04:03 | 0:04:09 | |

A villager still had a dried coelacanth which he let me see. | 0:04:09 | 0:04:13 | |

From what we know of the habits of the living coelacanth, | 0:04:16 | 0:04:19 | |

which is not much, | 0:04:19 | 0:04:21 | |

it seems that these rear fins are used for swimming | 0:04:21 | 0:04:25 | |

but the front ones are used for manoeuvring | 0:04:25 | 0:04:29 | |

and for helping the fish to clamber about | 0:04:29 | 0:04:31 | |

along the rocky bottom where it lives. | 0:04:31 | 0:04:34 | |

All the fins have fleshy bases to them. | 0:04:34 | 0:04:38 | |

The fishermen catch them at night from depths of 300 metres or so. | 0:04:38 | 0:04:42 | |

Once hooked, the fish fight valiantly, | 0:04:42 | 0:04:45 | |

and it may take all night to haul one to the surface. | 0:04:45 | 0:04:48 | |

So it's usually dead on arrival. | 0:04:48 | 0:04:51 | |

Scientists have still not been able to observe one alive. | 0:04:51 | 0:04:54 | |

Then, while we were in the Comoros, one was caught. | 0:04:54 | 0:04:58 | |

Although it was weak, it was still alive when the cameras arrived. | 0:04:58 | 0:05:02 | |

350 million years ago, fish with fins like these | 0:05:05 | 0:05:10 | |

were cruising the seas of the world. | 0:05:10 | 0:05:13 | |

Some living in shallow waters produced descendants | 0:05:13 | 0:05:15 | |

which eventually clambered onto the land, | 0:05:15 | 0:05:18 | |

while this creature's ancestors moved down to the unchanging depths, | 0:05:18 | 0:05:21 | |

there to remain unchanged themselves. | 0:05:21 | 0:05:25 | |

The Comorians catch one or two coelacanths a year. | 0:05:29 | 0:05:33 | |

They used not to value them much, for their flesh isn't good to eat. | 0:05:33 | 0:05:37 | |

Now, however, big rewards are offered by scientific institutions, | 0:05:37 | 0:05:41 | |

so the old man who caught this one will soon be rich. | 0:05:41 | 0:05:44 | |

Some researcher in a few weeks' time | 0:05:44 | 0:05:46 | |

will be absorbed in examining the structure of this fin | 0:05:46 | 0:05:51 | |

which scientists agree must resemble closely those limbs | 0:05:51 | 0:05:54 | |

that first took backboned animals onto the land. | 0:05:54 | 0:05:57 | |

But how about that second problem? The problem of breathing up on land. | 0:06:01 | 0:06:06 | |

The gills, which had served them well while swimming in water, | 0:06:06 | 0:06:10 | |

extracting dissolved oxygen, wouldn't work in the air. | 0:06:10 | 0:06:14 | |

How did the fish solve that problem? | 0:06:14 | 0:06:17 | |

Well, this is East Africa and it's the height of the dry season. | 0:06:17 | 0:06:21 | |

There is not a drop of water to be found in this parched landscape. | 0:06:21 | 0:06:26 | |

And yet, here, close by me, | 0:06:26 | 0:06:28 | |

there are fish that are living and breathing in air. | 0:06:28 | 0:06:33 | |

If only I can find them. | 0:06:33 | 0:06:34 | |

Six months ago, this was a pond several feet deep in water. | 0:06:54 | 0:06:59 | |

But as the dry season progressed, the water evaporated | 0:06:59 | 0:07:04 | |

and the fish in it burrowed down into this, | 0:07:04 | 0:07:09 | |

which was soft liquid mud and is now brick-hard. | 0:07:09 | 0:07:14 | |

And there, somewhere, they cocoon. | 0:07:14 | 0:07:19 | |

And that... | 0:07:29 | 0:07:31 | |

That looks like...the nose of one. | 0:07:32 | 0:07:37 | |

Poking out from the mud, there. | 0:07:37 | 0:07:40 | |

Now, if I take this and drop it in a tank of water, | 0:07:40 | 0:07:44 | |

it should seem as though the rains have come early, | 0:07:44 | 0:07:48 | |

and the fish should come to life. | 0:07:48 | 0:07:50 | |

As the water soaks in, the mud softens and falls away, | 0:08:13 | 0:08:17 | |

exposing a papery cocoon of dried mucus. | 0:08:17 | 0:08:20 | |

And there is the throat of this | 0:08:29 | 0:08:30 | |

extraordinary creature that can breathe in air and water. | 0:08:30 | 0:08:34 | |

It's a lungfish. | 0:08:34 | 0:08:36 | |

While its water-breathing apparatus, | 0:09:11 | 0:09:13 | |

the gills, are getting working again, | 0:09:13 | 0:09:16 | |

it snatches another gulp of air. | 0:09:16 | 0:09:18 | |

It's able to breathe air because it has, opening from its gut, | 0:09:30 | 0:09:34 | |

a long pouch lined with blood vessels, | 0:09:34 | 0:09:37 | |

and they can absorb gaseous oxygen through its moist lining. | 0:09:37 | 0:09:41 | |

The coelacanth has no lung, but it has got a simple leg, | 0:09:43 | 0:09:47 | |

that fin with a fleshy base to it, supported by bones. | 0:09:47 | 0:09:51 | |

Neither it nor the lungfish, therefore, | 0:09:53 | 0:09:56 | |

can be close to the ancestral creature that first moved to land. | 0:09:56 | 0:10:00 | |

But if those two crucial elements were to occur in one animal, | 0:10:01 | 0:10:05 | |

then such a creature would be a strong candidate. | 0:10:05 | 0:10:09 | |

And indeed, they do. | 0:10:09 | 0:10:11 | |

This fossil fish, from rocks 450 million years old, has them both. | 0:10:11 | 0:10:16 | |

It's called Eusthenopteron. | 0:10:16 | 0:10:18 | |

When the rock and scales around its fin are removed, | 0:10:18 | 0:10:22 | |

you can see the bones - one close to the body, | 0:10:22 | 0:10:26 | |

then two, then a group of small ones. | 0:10:26 | 0:10:29 | |

Exactly the pattern found in the limb of all land vertebrates. | 0:10:29 | 0:10:32 | |

And that adventurous ancestor may have been very like this. | 0:10:34 | 0:10:38 | |

But why should it have climbed onto the land? | 0:10:38 | 0:10:42 | |

Perhaps it was forced out by droughts. | 0:10:42 | 0:10:44 | |

Maybe it was tempted by food, the creatures that swarmed on the mud. | 0:10:44 | 0:10:49 | |

Whatever the reason, | 0:10:49 | 0:10:50 | |

its descendants came to spend more of their time out of water. | 0:10:50 | 0:10:55 | |

And over millions of years they evolved bodies | 0:10:55 | 0:10:57 | |

that were more suited to life on land | 0:10:57 | 0:10:59 | |

and became the first amphibians. | 0:10:59 | 0:11:02 | |

The vegetation of the time was different from that of today. | 0:11:21 | 0:11:25 | |

There were no flowering plants or conifers, | 0:11:25 | 0:11:27 | |

and one of the commonest was a kind of horsetail, | 0:11:27 | 0:11:30 | |

rather like these growing in the north of England, | 0:11:30 | 0:11:33 | |

except the horsetails then, | 0:11:33 | 0:11:36 | |

300 million years ago, grew to about 50 or 60 feet tall | 0:11:36 | 0:11:40 | |

and formed dense forests growing in swamps. | 0:11:40 | 0:11:43 | |

When they died, the horsetail trunks | 0:11:43 | 0:11:46 | |

fell into the water and formed a kind of peat. | 0:11:46 | 0:11:49 | |

Over the years, there were variations in the sea level | 0:11:49 | 0:11:52 | |

which flooded these swamps | 0:11:52 | 0:11:55 | |

and buried the peat beneath deposits of sand. | 0:11:55 | 0:11:58 | |

Under the accumulating weight of these sediments, | 0:11:58 | 0:12:02 | |

the peat then turned to coal. | 0:12:02 | 0:12:05 | |

And in the mine, you can see the sand that's been turned to stone | 0:12:18 | 0:12:24 | |

and beneath it, the compressed remains of the plants. | 0:12:24 | 0:12:28 | |

And in this particular seam have been found the bones | 0:12:28 | 0:12:33 | |

of some of the animals that crawled in those ancient swamps. | 0:12:33 | 0:12:38 | |

This is one of the most dramatic of them. | 0:12:38 | 0:12:42 | |

It's a skull. Here are its huge teeth, | 0:12:42 | 0:12:47 | |

which are simple teeth, rather like the peg-like teeth of the fish then. | 0:12:47 | 0:12:52 | |

We know that this creature had a paddle-shaped tail | 0:12:52 | 0:12:56 | |

and also four very good limbs. | 0:12:56 | 0:13:00 | |

So it really was a true amphibian. | 0:13:00 | 0:13:04 | |

It must have been a very formidable creature, too. | 0:13:04 | 0:13:06 | |

It grew to a length of about 12 feet. | 0:13:06 | 0:13:09 | |

There were many kinds of them, | 0:13:34 | 0:13:36 | |

and they dominated the land for 100 million years. | 0:13:36 | 0:13:40 | |

The largest amphibian alive today, the giant salamander from Japan, | 0:13:46 | 0:13:51 | |

grows to over 1.5 metres, four feet or so. | 0:13:51 | 0:13:55 | |

Even that is only a quarter as big as its ancestors. | 0:13:55 | 0:13:59 | |

Most of its living relations, the rest of the salamanders and newts, | 0:14:03 | 0:14:07 | |

are very much smaller, a few centimetres only from nose to tail. | 0:14:07 | 0:14:11 | |

Though newts spend much of their time out of water, | 0:14:14 | 0:14:17 | |

they don't go far from it. | 0:14:17 | 0:14:18 | |

In early spring, after hibernating, they must move back into it. | 0:14:18 | 0:14:22 | |

Their skin is permeable. It doesn't retain liquid very well. | 0:14:26 | 0:14:29 | |

If they dry out, they die. | 0:14:29 | 0:14:33 | |

They need to keep their skin moist, | 0:14:33 | 0:14:35 | |

for, like most amphibians, they breathe through it, | 0:14:35 | 0:14:38 | |

supplementing oxygen from their lungs | 0:14:38 | 0:14:41 | |

with more absorbed from the air. | 0:14:41 | 0:14:43 | |

And one final shackle keeps them tied to water. | 0:14:43 | 0:14:47 | |

They have to return to it to breed. | 0:14:47 | 0:14:50 | |

Once in water, | 0:14:55 | 0:14:57 | |

it sheds the thin outer skin used to protect it on land | 0:14:57 | 0:15:02 | |

and takes up an existence that is much more like that of a fish. | 0:15:02 | 0:15:06 | |

It often seems the newt is more at home here than on land, | 0:15:07 | 0:15:11 | |

and indeed, it retains many | 0:15:11 | 0:15:13 | |

characteristics of its fish ancestors. | 0:15:13 | 0:15:16 | |

The males become brightly coloured | 0:15:20 | 0:15:23 | |

and develop flamboyant crests along their backs. | 0:15:23 | 0:15:26 | |

Their courtship is reminiscent of that of fish. | 0:15:26 | 0:15:29 | |

They flex the frills along their backs | 0:15:29 | 0:15:32 | |

just as so many fish flex their fins, | 0:15:32 | 0:15:35 | |

and they beat the water with their tails, | 0:15:35 | 0:15:37 | |

sending powerful currents towards the female, | 0:15:37 | 0:15:41 | |

which she detects with a line of sensors | 0:15:41 | 0:15:43 | |

that resemble the lateral line system of the fish. | 0:15:43 | 0:15:46 | |

Two males are courting one female. She's in the middle, | 0:15:56 | 0:15:59 | |

without a crest. | 0:15:59 | 0:16:01 | |

The female lays several hundred eggs, each stuck to a leaf. | 0:16:06 | 0:16:12 | |

Development is swift. The tiny white sphere elongates. | 0:16:14 | 0:16:18 | |

Pigment appears. | 0:16:22 | 0:16:25 | |

And soon the young emerge, | 0:16:25 | 0:16:28 | |

and they're even more fish-like than their parents. | 0:16:28 | 0:16:30 | |

They have no legs, and breathe not with lungs but with feathery gills. | 0:16:30 | 0:16:35 | |

But slowly, their legs and lungs do develop, | 0:16:35 | 0:16:39 | |

and the newt tadpole for a short period can breathe both ways. | 0:16:39 | 0:16:43 | |

But there's one tadpole that remains like this all its life. | 0:16:48 | 0:16:53 | |

Its external gills are large and feathery and permanent. | 0:16:54 | 0:16:59 | |

It lives in one lake in Mexico and the Aztecs | 0:16:59 | 0:17:02 | |

called it the water monster, axolotl. | 0:17:02 | 0:17:05 | |

But the most surprising thing about this overgrown, eternal tadpole | 0:17:46 | 0:17:51 | |

is that it breeds in this condition. | 0:17:51 | 0:17:53 | |

The eggs start developing immediately. | 0:18:09 | 0:18:12 | |

The black part is the beginning of a body | 0:18:12 | 0:18:14 | |

which will grow round and enclose the cream-coloured yolk. | 0:18:14 | 0:18:18 | |

Food supply for further development. | 0:18:18 | 0:18:20 | |

Though the axolotl never changes | 0:18:27 | 0:18:29 | |

into a land-living salamander in the wild, | 0:18:29 | 0:18:31 | |

it has a close relative in Mexico which retains its options. | 0:18:31 | 0:18:35 | |

Sometimes it breeds like the axolotl, but if its lake dries, | 0:18:35 | 0:18:39 | |

it can turn into a normal land-living salamander. | 0:18:39 | 0:18:43 | |

The tadpoles, still with their feathery gills, | 0:18:43 | 0:18:46 | |

wriggle in the tepid, shallowing pools. | 0:18:46 | 0:18:48 | |

But as time passes, the gills disappear. | 0:18:52 | 0:18:55 | |

For now, the animal has developed lungs. | 0:18:55 | 0:18:58 | |

And eventually the little creature hauls itself up onto the mud. | 0:19:00 | 0:19:05 | |

But many salamanders aren't enthusiastic walkers | 0:19:05 | 0:19:09 | |

and show signs of abandoning the habit. | 0:19:09 | 0:19:13 | |

This one, from California, | 0:19:13 | 0:19:15 | |

has tiny legs and spends its time burrowing under stones. | 0:19:15 | 0:19:20 | |

One entire group of amphibians | 0:19:20 | 0:19:22 | |

has opted totally for this way of life | 0:19:22 | 0:19:26 | |

and lost their legs altogether - the Sicilians. | 0:19:26 | 0:19:29 | |

You might well confuse these with large earthworms. | 0:19:29 | 0:19:32 | |

This one comes from South-East Asia. | 0:19:33 | 0:19:36 | |

Its eyes are covered in skin, and to replace them, | 0:19:36 | 0:19:39 | |

it has small white feelers below its eye. | 0:19:39 | 0:19:42 | |

Their bodies have become elongated | 0:19:45 | 0:19:47 | |

and they've lost all traces of limbs. | 0:19:47 | 0:19:50 | |

Most of them don't come up to the surface until night. | 0:19:59 | 0:20:03 | |

But then you really see that they're not earthworms | 0:20:03 | 0:20:05 | |

solidly champing through soil. | 0:20:05 | 0:20:08 | |

Blind though they are, they're hunters. | 0:20:08 | 0:20:10 | |

This one comes from South America. | 0:20:14 | 0:20:18 | |

Sicilians constitute the smallest amphibian group. | 0:20:33 | 0:20:37 | |

160 species are known, compared with over twice that | 0:20:37 | 0:20:41 | |

for salamanders and newts. | 0:20:41 | 0:20:43 | |

But they're so unobtrusive | 0:20:43 | 0:20:45 | |

and so easily mistaken for worms and therefore ignored, | 0:20:45 | 0:20:49 | |

that there may well be many more kinds | 0:20:49 | 0:20:52 | |

still to be discovered in the soft, damp soils of the Tropics. | 0:20:52 | 0:20:56 | |

But most of the amphibians living in the world today | 0:20:56 | 0:20:59 | |

belong to a third group. | 0:20:59 | 0:21:01 | |

A group that doesn't live below ground like the Sicilians, | 0:21:01 | 0:21:04 | |

but above it, and far from having lost their legs, | 0:21:04 | 0:21:08 | |

they have developed their legs to a spectacular degree - | 0:21:08 | 0:21:13 | |

the frogs and toads. | 0:21:13 | 0:21:14 | |

And this is the king of them all, | 0:21:14 | 0:21:17 | |

the largest frog in the world, the Goliath frog. | 0:21:17 | 0:21:23 | |

It's a very rare animal that lives in a small part of West Africa. | 0:21:23 | 0:21:29 | |

In captivity, it lives on small birds and rats or mice, | 0:21:29 | 0:21:34 | |

and even fish. But in the wild, its diet is not quite so ambitious. | 0:21:34 | 0:21:40 | |

It takes dragonflies and other insects | 0:21:40 | 0:21:43 | |

as well as crabs from the bottom of the river. | 0:21:43 | 0:21:48 | |

It's a very good swimmer, | 0:21:48 | 0:21:50 | |

with very large webs at the bottom of its feet. | 0:21:50 | 0:21:54 | |

But these huge legs...these huge legs | 0:21:54 | 0:21:58 | |

also enable it to jump very well. | 0:21:58 | 0:22:01 | |

This particular one can jump nine or ten feet, ten times its body length. | 0:22:01 | 0:22:07 | |

But in the kingdom of frogs, that's not much. | 0:22:07 | 0:22:11 | |

Some of the smaller frogs can do very much better than that | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

and are dazzling athletes. | 0:22:14 | 0:22:16 | |

When each foot is webbed to form a parachute, | 0:22:28 | 0:22:32 | |

your leaps are spectacular indeed. | 0:22:32 | 0:22:35 | |

This is the famous flying frog, | 0:22:52 | 0:22:54 | |

though it'd be more accurate to call it a glider. | 0:22:54 | 0:22:58 | |

Even so, in one leap and glide, it can cover 15 metres or so, | 0:22:58 | 0:23:02 | |

say, 100 times its body length. | 0:23:02 | 0:23:05 | |

Several species have developed this talent. | 0:23:05 | 0:23:08 | |

There's one in Japan, another in Malaya, | 0:23:08 | 0:23:10 | |

and this one lives in Costa Rica. | 0:23:10 | 0:23:12 | |

Its feet are not only webbed but each toe ends in a sucker | 0:23:20 | 0:23:24 | |

so it can also cling to vertical leaves, if it has a mind to. | 0:23:24 | 0:23:29 | |

But its unique splendour is only revealed | 0:23:29 | 0:23:32 | |

when it leaps and opens its four extraordinary parachutes. | 0:23:32 | 0:23:37 | |

The flying frog seeks safety by launching itself into the air. | 0:24:19 | 0:24:23 | |

This frog takes refuge underground. | 0:24:23 | 0:24:26 | |

And its pointed nose gives it a very good start. | 0:24:26 | 0:24:29 | |

And then its legs provide a pile-driving thrust. | 0:24:36 | 0:24:39 | |

The holy cross toad of Australia also buries itself, | 0:24:44 | 0:24:48 | |

but it goes rear end first, with a different kind of leg action. | 0:24:48 | 0:24:52 | |

It's easy to understand why they hide. | 0:25:02 | 0:25:05 | |

Frogs to a hungry hunter appear appetising | 0:25:05 | 0:25:08 | |

and vulnerable with their soft bodies. | 0:25:08 | 0:25:11 | |

And indeed, many of them are. | 0:25:11 | 0:25:13 | |

But some have developed defences, and very surprising ones, too. | 0:25:13 | 0:25:19 | |

This grass snake is about to tackle an ordinary European toad. | 0:25:20 | 0:25:24 | |

The combination of standing on tiptoe | 0:25:42 | 0:25:45 | |

and inflating its body makes it look much bigger than it really is. | 0:25:45 | 0:25:49 | |

Whether this frightens the snake or baffles it, who can say? | 0:25:55 | 0:25:59 | |

Whatever its effect, it works. | 0:25:59 | 0:26:01 | |

The fire-bellied toad. Watch. | 0:26:04 | 0:26:05 | |

This extraordinary posture deters predators | 0:26:08 | 0:26:11 | |

by revealing the pattern on its stomach, | 0:26:11 | 0:26:14 | |

a combination of colours that's widely recognised | 0:26:14 | 0:26:17 | |

by animals as a warning. It's not all bluff, either. | 0:26:17 | 0:26:21 | |

All amphibians have mucus glands in their skin | 0:26:21 | 0:26:24 | |

which help keep them moist, | 0:26:24 | 0:26:26 | |

and some of these glands in the | 0:26:26 | 0:26:28 | |

fire-bellied toad produce a bitter-tasting poison. | 0:26:28 | 0:26:32 | |

Skin has become versatile in the amphibians for breathing, defence, | 0:26:32 | 0:26:37 | |

and it comes in all sizes, shapes and colours. | 0:26:37 | 0:26:41 | |

In South America, some frogs have developed defence | 0:26:50 | 0:26:54 | |

so far that they've become real killers. | 0:26:54 | 0:26:56 | |

The poison in their skins is so powerful, | 0:26:56 | 0:26:59 | |

it can paralyse a monkey or a bird immediately. | 0:26:59 | 0:27:03 | |

There are at least 20 different kinds of poison frogs | 0:27:03 | 0:27:06 | |

in Central and South America, | 0:27:06 | 0:27:08 | |

and conspicuousness is an important part of their defence strategy. | 0:27:08 | 0:27:13 | |

They don't want to be eaten by mistake, | 0:27:13 | 0:27:15 | |

for it's of no value to them if their attacker dies | 0:27:15 | 0:27:18 | |

soon after they've been eaten. | 0:27:18 | 0:27:20 | |

So they're all dressed in spectacular colours. | 0:27:20 | 0:27:23 | |

Colour is of no use at night when it can't be seen, | 0:27:23 | 0:27:26 | |

so unusually for frogs, | 0:27:26 | 0:27:28 | |

these little creatures are active in the daytime, | 0:27:28 | 0:27:31 | |

moving boldly around the forest, | 0:27:31 | 0:27:34 | |

confident and secure in their brilliant livery. | 0:27:34 | 0:27:37 | |

This particular species has good reason to be confident. | 0:27:45 | 0:27:49 | |

It has the most poisonous skin secretion of all. | 0:27:49 | 0:27:52 | |

It's only recently been discovered by science. | 0:27:52 | 0:27:55 | |

And just a tiny smear from its skin could kill a man. | 0:27:55 | 0:27:59 | |

The local Indians in Colombia use its poison on blowgun darts | 0:27:59 | 0:28:04 | |

by rubbing the tips on the backs of the living frogs. | 0:28:04 | 0:28:08 | |

One frog in Argentina has developed | 0:28:12 | 0:28:14 | |

a unique way of safeguarding against that, | 0:28:14 | 0:28:17 | |

and, at the same time, keeping itself watertight | 0:28:17 | 0:28:20 | |

when the weather's dry. | 0:28:20 | 0:28:22 | |

It gives itself a varnish. | 0:28:22 | 0:28:24 | |

There are many wax glands in its skin, | 0:28:30 | 0:28:33 | |

and when it feels its body is drying out, | 0:28:33 | 0:28:36 | |

it gives itself a good going-over to produce a thin, | 0:28:36 | 0:28:39 | |

waterproof covering. | 0:28:39 | 0:28:41 | |

But there is, of course, another opposite strategy. | 0:29:17 | 0:29:20 | |

If you're without defences of any kind, | 0:29:20 | 0:29:23 | |

then it may be much more effective to spend the day concealed, | 0:29:23 | 0:29:27 | |

camouflaged as part of a leaf. | 0:29:27 | 0:29:28 | |

Some conceal themselves not to escape, but to lurk in ambush. | 0:29:32 | 0:29:36 | |

This big toad will pounce on mice and fledglings as well as worms. | 0:29:36 | 0:29:41 | |

Cleaning earth and twigs from the worm is important, | 0:29:45 | 0:29:48 | |

for the toad has no teeth and swallows whole | 0:29:48 | 0:29:50 | |

whatever gets into its mouth. | 0:29:50 | 0:29:52 | |

It doesn't want any hard or spiky, inedible bits. | 0:29:52 | 0:29:56 | |

A tongue that can be stuck out is an amphibian invention. | 0:29:59 | 0:30:04 | |

No fish ever had one, and very effective it is, too. | 0:30:04 | 0:30:07 | |

The blink is an essential part of swallowing. | 0:30:12 | 0:30:15 | |

Frogs and toads have no bony base to their eye sockets, | 0:30:15 | 0:30:18 | |

so their eyeballs bulge down into their mouths. | 0:30:18 | 0:30:21 | |

When they blink, the underside of the eyes | 0:30:21 | 0:30:24 | |

helps to squeeze the food in its mouth back towards its throat. | 0:30:24 | 0:30:28 | |

Their tongue is not attached to the back of the mouth but to the front, | 0:30:28 | 0:30:31 | |

so they can stick it out much farther than we can, | 0:30:31 | 0:30:35 | |

which is very useful for an ungainly hunter without a neck like a toad. | 0:30:35 | 0:30:39 | |

Its end is sticky and muscular | 0:30:39 | 0:30:41 | |

and it grabs the worm with the underside. | 0:30:41 | 0:30:44 | |

And then the tongue has one final function. It lubricates the food | 0:30:44 | 0:30:50 | |

so it can be swallowed easily | 0:30:50 | 0:30:52 | |

without scratching the delicate membranes of the throat. | 0:30:52 | 0:30:56 | |

They eyes of the amphibians are fundamentally the same | 0:30:58 | 0:31:02 | |

as those of fish. There was no need to change them, | 0:31:02 | 0:31:05 | |

for they work as well in air as water. | 0:31:05 | 0:31:07 | |

But they have to be kept moist and clean, | 0:31:07 | 0:31:10 | |

so the amphibians have developed an ability to blink | 0:31:10 | 0:31:13 | |

and a membrane to wipe the surface. | 0:31:13 | 0:31:15 | |

Protection from strong light by closing the iris. | 0:31:27 | 0:31:31 | |

Or by using a membrane which still lets light in. | 0:31:32 | 0:31:36 | |

In air, however, you do need a different hearing apparatus | 0:31:38 | 0:31:42 | |

than in water. Eardrums. And with them came a voice. | 0:31:42 | 0:31:47 | |

Some frogs call during the day, like these edible frogs. | 0:31:47 | 0:31:51 | |

RASPING CALL | 0:31:51 | 0:31:53 | |

But most sing at night. Before the amphibians had crawled | 0:32:09 | 0:32:12 | |

out of the water 300 million years ago, | 0:32:12 | 0:32:16 | |

the only animal sounds on earth had been chirps of insects. | 0:32:16 | 0:32:19 | |

So the first animal chorus to break the silence of the land | 0:32:19 | 0:32:23 | |

may well have been like this. | 0:32:23 | 0:32:27 | |

WAILING CALL | 0:32:27 | 0:32:29 | |

The frog's lungs which blow air through its tiny vocal cords | 0:32:29 | 0:32:33 | |

are feeble. But resonating sacs bulging from the | 0:32:33 | 0:32:36 | |

angle of the jaws or the throat amplify it many times, | 0:32:36 | 0:32:40 | |

so that some calls can be heard for over a mile away. | 0:32:40 | 0:32:43 | |

HIGH-PITCHED CALL | 0:32:43 | 0:32:46 | |

SHORT CHIRPS | 0:32:53 | 0:32:55 | |

TWANGING CALL | 0:33:03 | 0:33:05 | |

HAMMERING CALL | 0:33:08 | 0:33:10 | |

VARIOUS CALLS | 0:33:13 | 0:33:15 | |

CHORUS OF CALLS | 0:34:10 | 0:34:12 | |

The cue for these choruses is usually a change in the weather, | 0:34:25 | 0:34:28 | |

for these songs are the prelude to mating. | 0:34:28 | 0:34:31 | |

In the Tropics, the trigger is usually | 0:34:31 | 0:34:33 | |

the onset of the rainy season. | 0:34:33 | 0:34:35 | |

THUNDER CLAPS | 0:34:37 | 0:34:38 | |

As the forest is drenched, | 0:35:05 | 0:35:07 | |

so the moisture-loving amphibians can get out, | 0:35:07 | 0:35:10 | |

seeking mates and laying eggs. | 0:35:10 | 0:35:13 | |

In this very rare species from Costa Rica, | 0:35:26 | 0:35:29 | |

the male is yellow, the female red and brown. | 0:35:29 | 0:35:32 | |

They abandon their eggs after they've laid them to return to land. | 0:35:37 | 0:35:41 | |

Streams and ponds and other such spawning sites | 0:35:41 | 0:35:44 | |

often swarm with fish that will eat any eggs or young they can find. | 0:35:44 | 0:35:48 | |

So hundreds must be laid if just one or two are to survive. | 0:35:48 | 0:35:52 | |

In temperate areas, breeding begins when the weather warms in spring. | 0:35:54 | 0:35:58 | |

European toads migrate from miles around to a single favoured pond | 0:35:58 | 0:36:02 | |

and assemble there in great numbers, all within a few days. | 0:36:02 | 0:36:06 | |

The breeding period may only last a week or so, | 0:36:06 | 0:36:09 | |

and towards the end, females with eggs still to lay become rare. | 0:36:09 | 0:36:13 | |

And the males, in their frenzy to couple with them, | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

clasp anything in the neighbourhood that moves, male or female, | 0:36:16 | 0:36:20 | |

and so form tangled, writhing groups. | 0:36:20 | 0:36:23 | |

These toads rely for breeding success on numbers. | 0:37:14 | 0:37:17 | |

A single female may deposit 6,000 eggs. | 0:37:17 | 0:37:22 | |

Mass production, be it in temperate or tropical places, | 0:37:22 | 0:37:24 | |

seems to be a very effective strategy. | 0:37:24 | 0:37:27 | |

These tadpoles, for example, developed from eggs | 0:37:33 | 0:37:37 | |

that were laid in enormous numbers | 0:37:37 | 0:37:39 | |

in pools beside this South American river. | 0:37:39 | 0:37:41 | |

But amphibians have another option. | 0:37:41 | 0:37:46 | |

They, after all, can climb up onto land, | 0:37:46 | 0:37:48 | |

so they can lay their eggs in places no fish could possibly reach. | 0:37:48 | 0:37:55 | |

When they had the land to themselves, | 0:37:55 | 0:37:58 | |

that must have been a particularly effective strategy. | 0:37:58 | 0:38:01 | |

Even today, there are many frogs | 0:38:01 | 0:38:03 | |

that go to quite extraordinary lengths | 0:38:03 | 0:38:06 | |

in order to lay their eggs away from ponds and rivers. | 0:38:06 | 0:38:10 | |

Of course, they have to keep their eggs moist, or they would dry out. | 0:38:10 | 0:38:15 | |

But around this river, at any rate, that's not too difficult. | 0:38:15 | 0:38:19 | |

These are the Kaieteur Falls on the Potaro River in Guyana. | 0:38:28 | 0:38:32 | |

The forest round here must be paradise for frogs, | 0:38:32 | 0:38:35 | |

for here, in effect, there is permanent rain. | 0:38:35 | 0:38:38 | |

And quite warm rain, at that. | 0:38:38 | 0:38:40 | |

The Potaro, above the falls, is 100 or so metres across, | 0:38:48 | 0:38:52 | |

and its waters fall sheer for over 200 metres. | 0:38:52 | 0:38:56 | |

Much of these great masses of falling water | 0:38:56 | 0:38:58 | |

turn to spray and drenching mists. | 0:38:58 | 0:39:01 | |

And as the mist comes swirling up, it condenses into drops | 0:39:09 | 0:39:15 | |

which fill the centre of such plants as this | 0:39:15 | 0:39:18 | |

and turn them into miniature ponds, idea for the frogs' purposes. | 0:39:18 | 0:39:23 | |

Inside this particular one lives a tiny, beautiful, golden frog. | 0:39:23 | 0:39:28 | |

It shares its minute pool with a few larvae, | 0:39:35 | 0:39:37 | |

but nothing that does it or its eggs any harm. | 0:39:37 | 0:39:40 | |

There are many plants with water-filled chalices in their | 0:39:51 | 0:39:54 | |

centres in the South American rainforest, | 0:39:54 | 0:39:56 | |

and many of them grow high up on branches, | 0:39:56 | 0:40:00 | |

their roots dangling in the moist air. | 0:40:00 | 0:40:03 | |

So they are, in effect, ponds up trees. | 0:40:03 | 0:40:06 | |

They provide the frogs with little oases | 0:40:06 | 0:40:08 | |

where they can live and spawn away from predators for generations | 0:40:08 | 0:40:13 | |

without ever coming down to the ground. | 0:40:13 | 0:40:16 | |

In the African savannahs, with much less rain, | 0:40:20 | 0:40:23 | |

there are no such plants, but there is a frog | 0:40:23 | 0:40:26 | |

that manages to breed in the trees. | 0:40:26 | 0:40:30 | |

Instead of water, it uses foam. The trick is done at night. | 0:40:30 | 0:40:36 | |

The female excretes a liquid | 0:40:42 | 0:40:44 | |

which she beats into a lather with her hind legs. | 0:40:44 | 0:40:48 | |

The male joins her and fertilises | 0:40:48 | 0:40:50 | |

the 150 or so eggs which she deposits in the foam. | 0:40:50 | 0:40:53 | |

The sun will bake the outside into a hard crust. | 0:40:53 | 0:40:57 | |

But inside, it remains liquid, and there the eggs develop. | 0:40:57 | 0:41:01 | |

The nests are always made above water, | 0:41:01 | 0:41:04 | |

so in due time, when the crust cracks and the young ooze out, | 0:41:04 | 0:41:08 | |

they drop straight down into a river or a swamp. | 0:41:08 | 0:41:10 | |

This frog from South America also | 0:41:39 | 0:41:41 | |

has a way of keeping its eggs away from the river. | 0:41:41 | 0:41:45 | |

Here, however, where the air is more humid, | 0:41:45 | 0:41:47 | |

it doesn't need foam, | 0:41:47 | 0:41:49 | |

because the jelly surrounding its eggs doesn't dry out. | 0:41:49 | 0:41:52 | |

The young tadpoles develop inside the jelly, like many other species, | 0:41:52 | 0:41:56 | |

but these stay there while they go through | 0:41:56 | 0:41:58 | |

most of their larval development. | 0:41:58 | 0:42:00 | |

They even develop gills inside the egg. | 0:42:11 | 0:42:15 | |

And their hearts begin to beat. | 0:42:21 | 0:42:24 | |

Eventually, they too will emerge and drop down into water. | 0:42:27 | 0:42:33 | |

The tadpoles of one Caribbean frog have managed, astonishingly, | 0:42:33 | 0:42:36 | |

to dispense with water altogether for their development. | 0:42:36 | 0:42:40 | |

The whistling frog lays a cluster of eggs on the ground. | 0:42:40 | 0:42:43 | |

They're only small, but inside each there is liquid. | 0:42:43 | 0:42:46 | |

And in it, the young develop not only to the tadpole stage, | 0:42:46 | 0:42:50 | |

but beyond. | 0:42:50 | 0:42:52 | |

Their tiny stomachs are full of yolk | 0:43:06 | 0:43:08 | |

that must fuel their entire development. | 0:43:08 | 0:43:11 | |

The front legs are formed. | 0:43:13 | 0:43:15 | |

And so are the back legs. | 0:43:23 | 0:43:24 | |

And at last, it becomes virtually a tiny, | 0:43:27 | 0:43:29 | |

fully-developed replica of its parent. | 0:43:29 | 0:43:32 | |

On its nose, it has a tiny spike, | 0:43:46 | 0:43:49 | |

and with that, it punctures the egg membrane. | 0:43:49 | 0:43:52 | |

And after about 18 days, it hatches, having eliminated altogether | 0:43:52 | 0:43:56 | |

the tadpole's normal need for open water. | 0:43:56 | 0:44:00 | |

Laying eggs away from water and its dangers | 0:44:00 | 0:44:02 | |

is a successful breeding strategy. | 0:44:02 | 0:44:05 | |

But yet other frogs have taken a different line. | 0:44:05 | 0:44:08 | |

Instead of abandoning their eggs in a safe place, | 0:44:08 | 0:44:12 | |

they stay with them and look after them. | 0:44:12 | 0:44:15 | |

The midwife toad lives in Europe. Its name is not accurate | 0:44:15 | 0:44:19 | |

because it's the male that carries the eggs entangled round his legs. | 0:44:19 | 0:44:25 | |

There may be 60 or so of them, | 0:44:25 | 0:44:27 | |

and he carries them for six or seven weeks. | 0:44:27 | 0:44:30 | |

At hatching time, he takes them down to water and the tadpoles swim away. | 0:44:30 | 0:44:35 | |

Some toads spend all their time in water. | 0:44:38 | 0:44:41 | |

This pipa from Brazil, | 0:44:41 | 0:44:43 | |

instead of laying and abandoning 6,000 eggs like the European toad, | 0:44:43 | 0:44:47 | |

lays a mere hundred or so. | 0:44:47 | 0:44:49 | |

But they look after them in the most extraordinary manner. | 0:44:53 | 0:44:57 | |

The male, with these elegant movements of its hind feet, | 0:44:57 | 0:45:02 | |

takes care that as many eggs as possible | 0:45:02 | 0:45:04 | |

are gathered on the female's back. | 0:45:04 | 0:45:07 | |

And they stick. | 0:45:11 | 0:45:13 | |

Then the skin on the female's back begins to swell. | 0:45:39 | 0:45:43 | |

The eggs rapidly become embedded in it. | 0:45:45 | 0:45:48 | |

Soon, a membrane grows over them to enclose them completely. | 0:45:52 | 0:45:56 | |

After only 30 hours, almost all the eggs have disappeared | 0:46:00 | 0:46:04 | |

and the skin is complete again. | 0:46:04 | 0:46:07 | |

After nearly three weeks, it's moving. | 0:46:07 | 0:46:10 | |

And then, after another three weeks or so, the young begin to emerge. | 0:46:12 | 0:46:17 | |

Now the parent leaves the young to fend for themselves. | 0:46:45 | 0:46:48 | |

But at least they're now independent swimmers, | 0:46:48 | 0:46:51 | |

able to find hiding places. | 0:46:51 | 0:46:53 | |

So a higher proportion is likely to | 0:46:53 | 0:46:56 | |

survive than if they'd been abandoned as eggs. | 0:46:56 | 0:46:59 | |

This little South American frog | 0:47:01 | 0:47:03 | |

also keeps her eggs and young on her back | 0:47:03 | 0:47:05 | |

in a pouch with an opening just above the base of her spine. | 0:47:05 | 0:47:09 | |

Her developing young remain inside it for three months or more, | 0:47:17 | 0:47:20 | |

until at last she releases them into a pool as tadpoles. | 0:47:20 | 0:47:24 | |

They're on their way towards their final change into adults, | 0:47:32 | 0:47:36 | |

for they have back legs. | 0:47:36 | 0:47:38 | |

These many differing ways of carrying their developing young | 0:47:43 | 0:47:47 | |

may seem extraordinary enough, but other frogs in South America | 0:47:47 | 0:47:51 | |

actually retain their tadpoles inside their bodies, | 0:47:51 | 0:47:55 | |

in the most unlikely parts. | 0:47:55 | 0:47:58 | |

There is one which calls in the beech forests of southern Chile. | 0:47:58 | 0:48:02 | |

It's Darwin's frog. | 0:48:02 | 0:48:03 | |

These creatures, only a few centimetres long, | 0:48:22 | 0:48:25 | |

are all males, even though they vary in colour. | 0:48:25 | 0:48:28 | |

They're still calling but the breeding is over. | 0:48:28 | 0:48:30 | |

The females have laid their eggs in groups of 20 or 30 on the forest floor. | 0:48:30 | 0:48:35 | |

As soon as the males see a movement in the eggs, they will, apparently, eat them. | 0:48:35 | 0:48:41 | |

Each male may take a dozen or so but he doesn't swallow them. | 0:48:41 | 0:48:44 | |

Instead, they go into his vocal sac down the front of his throat | 0:48:44 | 0:48:48 | |

and there they develop...and wriggle. | 0:48:48 | 0:48:52 | |

The males sit about, struck dumb by their own offspring. | 0:48:52 | 0:48:56 | |

After some weeks, their extraordinary | 0:48:56 | 0:48:58 | |

vocal pregnancy comes to an end. | 0:48:58 | 0:49:01 | |

And here is that amazing birth once again, in slow motion. | 0:49:21 | 0:49:25 | |

The male's vocal sac is now ready again for singing, | 0:49:35 | 0:49:39 | |

before it's turned next season once more into a nursery. | 0:49:39 | 0:49:43 | |

The prize for the care of the young must surely go to this frog, | 0:49:45 | 0:49:49 | |

that lives only on a remote mountain in West Africa. | 0:49:49 | 0:49:52 | |

The female, only about a centimetre long, | 0:49:55 | 0:49:57 | |

keeps the eggs inside her distended oviducts | 0:49:57 | 0:50:00 | |

and holds them there throughout the nine months of the dry season. | 0:50:00 | 0:50:04 | |

As they grow, she secretes internally some white flakes. | 0:50:04 | 0:50:09 | |

The tadpoles, moving around freely inside the oviduct, | 0:50:09 | 0:50:13 | |

eat the flakes and digest them in | 0:50:13 | 0:50:15 | |

their gut just as they would do in the pond. | 0:50:15 | 0:50:19 | |

When the rain comes, she gives birth. | 0:50:19 | 0:50:22 | |

Her stomach and oviduct don't have muscles which can expel the young, | 0:50:22 | 0:50:27 | |

so she does it by bracing her body against the ground with her forelegs | 0:50:27 | 0:50:31 | |

and inflating her lungs so they bulge into her abdomen | 0:50:31 | 0:50:35 | |

and squeeze the young out. | 0:50:35 | 0:50:37 | |

And they're born fully-formed froglets, | 0:50:37 | 0:50:41 | |

a triumph of parental care. | 0:50:41 | 0:50:44 | |

By providing their young with moisture of some kind | 0:50:44 | 0:50:47 | |

and using all these varying and astonishing techniques, | 0:50:47 | 0:50:51 | |

frogs and toads have managed to colonise almost all the world. | 0:50:51 | 0:50:54 | |

Even so, you would think that with their thin, permeable skins, | 0:50:54 | 0:50:58 | |

they would never be able to survive in the Australian desert. | 0:50:58 | 0:51:02 | |

But one or two species manage to live even here. | 0:51:02 | 0:51:05 | |

They spend nearly all their lives in the ground, away from the sun. | 0:51:05 | 0:51:10 | |

They may lie here for years, | 0:51:10 | 0:51:12 | |

waiting, but eventually the rains do come. | 0:51:12 | 0:51:16 | |

When the frogs burrowed down here during the last rains, | 0:51:29 | 0:51:31 | |

they were bloated with water, | 0:51:31 | 0:51:33 | |

and they've conserved it in their chambers | 0:51:33 | 0:51:35 | |

by sealing themselves inside a membrane secreted from their skins. | 0:51:35 | 0:51:40 | |

But when the rain arrives again, they must get rid of their packaging | 0:51:40 | 0:51:45 | |

to be ready for breeding. | 0:51:45 | 0:51:48 | |

In the brief period when the desert is wet, | 0:52:04 | 0:52:07 | |

these frogs will dig themselves out and mate, | 0:52:07 | 0:52:10 | |

and their tadpoles will develop | 0:52:10 | 0:52:12 | |

in the few days there's water in the pools. | 0:52:12 | 0:52:15 | |

Then, as the desert dries out, the young frogs will bury themselves | 0:52:15 | 0:52:20 | |

and remain underground for perhaps five years or more. | 0:52:20 | 0:52:24 | |

In times of drought, the desert aborigines | 0:52:31 | 0:52:34 | |

search eagerly for frogs like this, and this is why. | 0:52:34 | 0:52:39 | |

If you squeeze one, you can get a reasonable drink of water from it. | 0:52:39 | 0:52:43 | |

It's tasteless and really quite drinkable. | 0:53:01 | 0:53:04 | |

And now I'm going to have to find a pond for this little creature, | 0:53:04 | 0:53:08 | |

where it will survive until the next rains come. | 0:53:08 | 0:53:11 | |

For the fact of the matter is | 0:53:11 | 0:53:13 | |

that its success as a desert liver is limited. | 0:53:13 | 0:53:16 | |

It can only be active and breed | 0:53:16 | 0:53:18 | |

during that short period when there's rain. | 0:53:18 | 0:53:21 | |

In order to survive in a desert and breed there, | 0:53:21 | 0:53:24 | |

if necessary with no rain at all, | 0:53:24 | 0:53:27 | |

you need a device that no frog or amphibian has got. | 0:53:27 | 0:53:32 | |

This. | 0:53:34 | 0:53:35 | |

An egg with a waterproof shell. | 0:53:35 | 0:53:39 | |

That was the next great evolutionary breakthrough. | 0:53:39 | 0:53:43 | |

And it was achieved by the reptiles. | 0:53:43 | 0:53:46 | |

The astonishment is that without it, | 0:53:46 | 0:53:49 | |

amphibians managed to colonise so much of the world. | 0:53:49 | 0:53:53 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:54:15 | 0:54:18 |