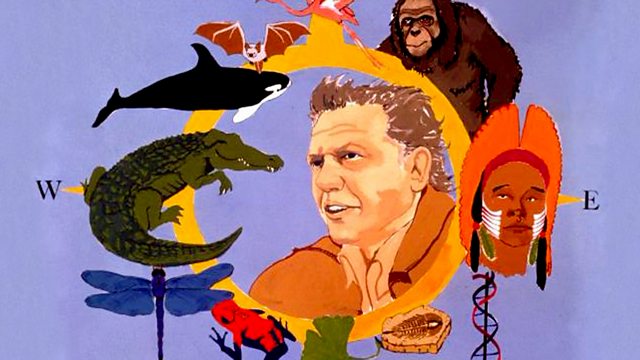

Victors of the Dry Land Life on Earth

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Victors of the Dry Land. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

If there's one place in the world where reptiles still rule, | 0:01:21 | 0:01:24 | |

it's here in the Galapagos Islands. | 0:01:24 | 0:01:28 | |

The ancestors of the reptiles, the amphibians, had wet, permeable skins. | 0:01:28 | 0:01:33 | |

As a consequence, they couldn't exist for long away from water. | 0:01:34 | 0:01:39 | |

Reptiles, however, like these marine iguanas, are not so restricted. | 0:01:39 | 0:01:44 | |

They can survive in places where amphibians | 0:01:44 | 0:01:46 | |

would roast to death in minutes. | 0:01:46 | 0:01:48 | |

Out on the scorching lava fields, the iguanas lie unprotected | 0:01:48 | 0:01:53 | |

in the ferocious Equatorial sun. | 0:01:53 | 0:01:55 | |

They can do so because of the major innovation | 0:01:55 | 0:01:58 | |

made by the first reptiles - | 0:01:58 | 0:02:00 | |

the nature of their skin. | 0:02:00 | 0:02:02 | |

It's not moist like a frog's, but tough, covered with scales, | 0:02:02 | 0:02:07 | |

and, most crucial of all, it's practically watertight. | 0:02:07 | 0:02:11 | |

This skin has enabled reptiles | 0:02:11 | 0:02:13 | |

to colonise the hottest and driest places on earth. | 0:02:13 | 0:02:16 | |

And this is one of them. | 0:02:16 | 0:02:17 | |

The Namib desert in south-western Africa. | 0:02:17 | 0:02:20 | |

The sand here gets so hot, it scorches the skin, | 0:02:35 | 0:02:38 | |

and even the sole of a reptile's foot can get burned, | 0:02:38 | 0:02:42 | |

so when the sun is too much, | 0:02:42 | 0:02:44 | |

this little lizard gets relief by gymnastics. | 0:02:44 | 0:02:47 | |

The scales of the reptiles' skin are dead - | 0:03:00 | 0:03:03 | |

horny outgrowths, like our fingernails. | 0:03:03 | 0:03:05 | |

The reptiles use them for all kinds of purposes. | 0:03:05 | 0:03:09 | |

No bird would want to eat the Australian thorny devil | 0:03:09 | 0:03:12 | |

with scales like these. | 0:03:12 | 0:03:14 | |

Scales are used to protect the body against wear and tear. | 0:03:16 | 0:03:20 | |

Reptile legs stick out at the side rather than give support underneath. | 0:03:20 | 0:03:24 | |

Although this shingleback drags its belly along the ground, | 0:03:24 | 0:03:28 | |

its tough, heavy scales prevent damage. | 0:03:28 | 0:03:31 | |

The scales can be of different sizes. | 0:03:35 | 0:03:38 | |

Small where the skin needs to be flexible, | 0:03:38 | 0:03:40 | |

and large and robust, especially on the head, to reinforce the skull. | 0:03:40 | 0:03:45 | |

In some lizards, the horny skin and scales | 0:03:48 | 0:03:50 | |

are fashioned into dramatic headgear. | 0:03:50 | 0:03:53 | |

Sometimes the adornments are designed not just to protect | 0:04:21 | 0:04:26 | |

but to scare enemies, as in the bearded dragon. | 0:04:26 | 0:04:29 | |

The Australian frilled lizard, like most of them, is a bluffer. | 0:04:45 | 0:04:49 | |

Its great ruff is no more than its scaly skin | 0:04:49 | 0:04:52 | |

supported by bones from the throat. | 0:04:52 | 0:04:54 | |

In fact, it's a relatively harmless creature with no offensive weapons. | 0:04:54 | 0:04:59 | |

If its bluff doesn't work... | 0:04:59 | 0:05:01 | |

..it can run for it. | 0:05:03 | 0:05:05 | |

The horned iguana from the West Indies | 0:05:29 | 0:05:32 | |

is one of the most heavily armoured of all lizards. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:35 | |

Big, powerful, it's the rhinoceros of the reptile world. | 0:05:35 | 0:05:39 | |

There's one group of lizards which, | 0:05:42 | 0:05:44 | |

unusually for reptiles, is most active at night. | 0:05:44 | 0:05:47 | |

The geckos. | 0:05:47 | 0:05:49 | |

Some of their scales are the most complicated of all. | 0:05:54 | 0:05:58 | |

Geckos can run up vertical walls, even panes of glass. | 0:05:58 | 0:06:02 | |

The trick is done by scales on the soles of the feet. | 0:06:02 | 0:06:05 | |

Each scale is branched and carries hundreds of microscopic hairs, | 0:06:05 | 0:06:09 | |

invisible to the naked eye. | 0:06:09 | 0:06:12 | |

The electron microscope shows that each ends in a cluster of tiny hooks | 0:06:12 | 0:06:17 | |

that enables the gecko to hang on to virtually anything. | 0:06:17 | 0:06:20 | |

The reptiles' skin is rich in pigment cells | 0:06:24 | 0:06:26 | |

which can provide marvellous disguises. | 0:06:26 | 0:06:28 | |

The Madagascan gecko is coloured | 0:06:28 | 0:06:31 | |

exactly like the bark it always sits on. | 0:06:31 | 0:06:34 | |

The chameleon can vary the shade of green in its skin | 0:06:37 | 0:06:40 | |

so that it becomes invisible among leaves. | 0:06:40 | 0:06:44 | |

The earless dragon from central Australia | 0:06:46 | 0:06:48 | |

is obvious when it's feeding. | 0:06:48 | 0:06:50 | |

But when it's motionless, | 0:06:52 | 0:06:54 | |

it's difficult to distinguish it from pebbles. | 0:06:54 | 0:06:58 | |

THUNDER ROLLS | 0:07:05 | 0:07:07 | |

For the biggest scales of all, we go back to the Galapagos Islands | 0:07:11 | 0:07:15 | |

and look for their most famous inhabitant, | 0:07:15 | 0:07:18 | |

the giant tortoise. | 0:07:18 | 0:07:20 | |

Its scales are supported from beneath by massive, bony plates | 0:07:20 | 0:07:24 | |

so that the animal is as impregnable as a tank. | 0:07:24 | 0:07:27 | |

The mountain slopes where they live are dry for much of the year, | 0:07:32 | 0:07:36 | |

but their watertight skin | 0:07:36 | 0:07:38 | |

keeps their liquid demands to a minimum. | 0:07:38 | 0:07:41 | |

But even so, they have to top up this water, | 0:07:41 | 0:07:44 | |

and this is one of the few waterholes in the crater. | 0:07:44 | 0:07:49 | |

These few are just wallowing in the mud, | 0:07:49 | 0:07:51 | |

but at this moment, a shower has started, | 0:07:51 | 0:07:54 | |

and it'll fill little puddles here in the mud, | 0:07:54 | 0:07:57 | |

and soon tortoises from all over the crater will stream down here | 0:07:57 | 0:08:03 | |

to sip in those puddles. | 0:08:03 | 0:08:05 | |

Since the reptiles were the first backboned animals | 0:08:20 | 0:08:23 | |

to live completely away from water, | 0:08:23 | 0:08:26 | |

they must have been the first creatures to develop real thirsts. | 0:08:26 | 0:08:30 | |

And they have vast capacities. | 0:08:31 | 0:08:34 | |

They can store several gallons of liquid in their bodies. | 0:08:34 | 0:08:38 | |

So when water is about, they make the best of it | 0:08:38 | 0:08:40 | |

and fill their reserve tanks. | 0:08:40 | 0:08:42 | |

This may well be their last drink for months. | 0:08:42 | 0:08:46 | |

The tortoises are an extremely ancient group. | 0:08:53 | 0:08:56 | |

They appeared right at the dawn of the age of reptiles, | 0:08:56 | 0:09:00 | |

some 180 million years ago. | 0:09:00 | 0:09:02 | |

They saw the dinosaurs come and vanish. | 0:09:02 | 0:09:06 | |

And they continued, as far as we can judge from their fossils, | 0:09:06 | 0:09:10 | |

almost unchanged right until today. | 0:09:10 | 0:09:13 | |

Their armoured shell may be unwieldy, but it's a most successful defence. | 0:09:30 | 0:09:36 | |

Inside it, nothing can reach them. | 0:09:36 | 0:09:39 | |

After a night of rain, the pools are full of water. | 0:09:56 | 0:10:01 | |

They're also full of wallowing tortoises. | 0:10:07 | 0:10:11 | |

Why, we just don't know, although some say | 0:10:11 | 0:10:14 | |

it's a way of keeping warm at night and cool by day. | 0:10:14 | 0:10:17 | |

Temperature control is something all reptiles must achieve, | 0:10:20 | 0:10:24 | |

and some on the Galapagos | 0:10:24 | 0:10:26 | |

must cope with the scorching Equatorial sun | 0:10:26 | 0:10:28 | |

without the benefit of fresh water. | 0:10:28 | 0:10:31 | |

Marine iguanas live down on the hot, black lava rocks. | 0:10:37 | 0:10:42 | |

Although their skin is watertight, it's a very poor insulator. | 0:10:42 | 0:10:47 | |

That may seem to be a limitation in this heat, | 0:10:47 | 0:10:49 | |

but they've turned it to their advantage. | 0:10:49 | 0:10:52 | |

We tend to think of reptiles as sluggish, cold-blooded creatures. | 0:11:00 | 0:11:05 | |

But that's a mistaken view. | 0:11:05 | 0:11:07 | |

Some of them, like these marine iguanas, for example, | 0:11:07 | 0:11:11 | |

can maintain a higher working body temperature than us. | 0:11:11 | 0:11:15 | |

In fact, the misleading term "cold-blooded" | 0:11:15 | 0:11:18 | |

simply means the animals can't generate | 0:11:18 | 0:11:21 | |

their own body heat internally. | 0:11:21 | 0:11:24 | |

Instead, they get it from the sun by sunbathing. | 0:11:24 | 0:11:28 | |

What's more, they can control the amount of heat they absorb | 0:11:28 | 0:11:33 | |

to within very fine limits. | 0:11:33 | 0:11:35 | |

At the moment, it's early morning. | 0:11:42 | 0:11:44 | |

The night has been relatively cold | 0:11:44 | 0:11:47 | |

and the iguanas are out on the rocks | 0:11:47 | 0:11:49 | |

soaking up all the heat the sun provides. | 0:11:49 | 0:11:52 | |

For until they're warm, | 0:11:52 | 0:11:53 | |

their body chemistry won't produce the power they need to be active. | 0:11:53 | 0:11:57 | |

But overheating can be as dangerous as chilling. | 0:12:09 | 0:12:12 | |

The iguanas can't cool themselves by sweating, | 0:12:12 | 0:12:15 | |

for the reptiles' skin hasn't got any sweat glands. | 0:12:15 | 0:12:20 | |

So when, around midday, the sun gets too warm for comfort, | 0:12:20 | 0:12:24 | |

they move down into clefts in the rocks and hang there in cool shadow. | 0:12:24 | 0:12:29 | |

By choosing their resting places with care, | 0:12:37 | 0:12:40 | |

they can keep their body temperature | 0:12:40 | 0:12:43 | |

very close to 37 degrees centigrade at all times. | 0:12:43 | 0:12:46 | |

When they've reached their working temperature, they can go for a swim. | 0:12:49 | 0:12:54 | |

These reptiles feed on seaweed, and some of it they get by diving. | 0:12:59 | 0:13:05 | |

But the sun-warmed iguanas have a problem. | 0:13:05 | 0:13:08 | |

The sea is particularly cold here. | 0:13:09 | 0:13:12 | |

A current comes straight up from the Antarctic, | 0:13:12 | 0:13:15 | |

and it's easy to get chilled and torpid. | 0:13:15 | 0:13:17 | |

So they overcome the difficulty | 0:13:17 | 0:13:20 | |

by withdrawing warm blood into the centre of their body. | 0:13:20 | 0:13:24 | |

It simply delays the cooling process. | 0:13:24 | 0:13:27 | |

However, the marine iguanas must not stay out too long. | 0:13:39 | 0:13:42 | |

Should they become over-chilled, they will lose their energy | 0:13:44 | 0:13:48 | |

and no longer have the strength | 0:13:48 | 0:13:50 | |

to cling to the rocks and resist the waves. | 0:13:50 | 0:13:53 | |

By mid-afternoon, they're all back on the sunbathing rocks, | 0:14:04 | 0:14:08 | |

eager to get warmed up again. | 0:14:08 | 0:14:10 | |

To get warm quickly, you need to expose | 0:14:22 | 0:14:24 | |

as much as possible of your surface to the sun and warm rocks. | 0:14:24 | 0:14:28 | |

So the most recently emerged iguanas slump out, spread-eagled, | 0:14:28 | 0:14:32 | |

just like exhausted human bathers after a cold swim. | 0:14:32 | 0:14:36 | |

It's vital for them to warm up | 0:14:36 | 0:14:38 | |

because without warmth, they cannot digest their meals. | 0:14:38 | 0:14:42 | |

This is where they will all congregate as the day cools | 0:14:48 | 0:14:51 | |

to collect the last rays of the sinking sun. | 0:14:51 | 0:14:56 | |

One advantage of generating your own body heat internally, | 0:14:56 | 0:14:59 | |

as we and all mammals do, is that, when the sun goes down, | 0:14:59 | 0:15:03 | |

we can remain active and we can live in cold climates. | 0:15:03 | 0:15:07 | |

But the price we pay for those privileges is very high. | 0:15:07 | 0:15:11 | |

Something like 80% of the energy in the food we eat | 0:15:11 | 0:15:14 | |

goes to maintaining our body temperatures | 0:15:14 | 0:15:17 | |

at around 38 degrees centigrade. | 0:15:17 | 0:15:19 | |

The reptiles' system, getting heat directly from the sun, | 0:15:19 | 0:15:23 | |

is much more economical. | 0:15:23 | 0:15:24 | |

A reptile can survive on 10% of the food | 0:15:24 | 0:15:27 | |

a mammal of a similar size would require. | 0:15:27 | 0:15:31 | |

And so, although they can't live in the Arctic, | 0:15:31 | 0:15:33 | |

they can survive on low-calorie foods, | 0:15:33 | 0:15:36 | |

like the seaweed these marine iguanas eat, | 0:15:36 | 0:15:40 | |

and live in great numbers in places where food is very scarce, | 0:15:40 | 0:15:45 | |

such as deserts. | 0:15:45 | 0:15:46 | |

A chameleon, for example, can flourish in barren areas, | 0:16:08 | 0:16:12 | |

provided that every few days | 0:16:12 | 0:16:14 | |

it catches one reasonably-sized insect. | 0:16:14 | 0:16:18 | |

The chameleon's talent for changing colour | 0:16:29 | 0:16:32 | |

serves not only to give it different disguises | 0:16:32 | 0:16:35 | |

but to express its emotions. | 0:16:35 | 0:16:37 | |

It goes black with rage | 0:16:37 | 0:16:39 | |

and becomes brightly coloured when courting, | 0:16:39 | 0:16:42 | |

as many reptiles do. | 0:16:42 | 0:16:45 | |

Anolis lizards display with extensible throat pouches, | 0:16:45 | 0:16:48 | |

each species with its own particular colour. | 0:16:48 | 0:16:52 | |

Nodding reinforces the effect. It's like waving a flag. | 0:16:59 | 0:17:03 | |

This is the rare green iguana from Fiji. | 0:17:06 | 0:17:10 | |

His courting colours are permanently on display, | 0:17:10 | 0:17:13 | |

for only the male has black stripes. | 0:17:13 | 0:17:15 | |

He doesn't have a throat pouch, but, like many lizards, | 0:17:23 | 0:17:26 | |

uses head nodding to signal his status as a male in breeding fettle. | 0:17:26 | 0:17:32 | |

By comparison, the female is plainer and not nearly so demonstrative. | 0:17:35 | 0:17:40 | |

The Galapagos iguanas also nod. | 0:17:45 | 0:17:47 | |

For them, as for others, the gesture serves a double purpose - | 0:17:47 | 0:17:52 | |

not only to impress the females, but to warn off rival males. | 0:17:52 | 0:17:56 | |

Each species has its own rhythm. | 0:17:56 | 0:18:00 | |

The land iguanas have a slightly different language. | 0:18:00 | 0:18:04 | |

A nose-to-nose nodding session | 0:18:06 | 0:18:07 | |

is enough to settle a territorial dispute between these males. | 0:18:07 | 0:18:11 | |

Eventually, all these displays lead to the desired consummation. | 0:18:37 | 0:18:42 | |

The reptiles were the first vertebrates | 0:19:05 | 0:19:08 | |

for whom internal fertilisation was essential. | 0:19:08 | 0:19:11 | |

Their immediate ancestors, the amphibians, had no need for it. | 0:19:11 | 0:19:15 | |

They mated in water, | 0:19:15 | 0:19:17 | |

and sperms shed from the body could swim to the eggs. | 0:19:17 | 0:19:20 | |

But out on dry land, the male reptiles had to find | 0:19:20 | 0:19:24 | |

some other way of ensuring that sperm met egg - | 0:19:24 | 0:19:27 | |

by placing it inside the female's body. | 0:19:27 | 0:19:30 | |

And it sometimes seems that that process for these antique creatures | 0:19:30 | 0:19:35 | |

is still a very clumsy and laborious business. | 0:19:35 | 0:19:39 | |

In due course, that produces | 0:19:42 | 0:19:44 | |

the second of the great reptilian innovations. | 0:19:44 | 0:19:47 | |

Their waterproof skins had enabled them | 0:19:47 | 0:19:50 | |

to live in the driest places on Earth. | 0:19:50 | 0:19:53 | |

But that was of limited value if they had to retreat | 0:19:53 | 0:19:56 | |

to find open water in which to lay eggs, as the amphibians have to do. | 0:19:56 | 0:20:01 | |

The reptiles solved that problem by producing this. | 0:20:01 | 0:20:07 | |

The waterproof egg. | 0:20:07 | 0:20:09 | |

In effect, it's a tiny pond encapsulated in parchment and shell | 0:20:09 | 0:20:14 | |

in which their young can pass through what amounts to the tadpole stage. | 0:20:14 | 0:20:18 | |

The Fijian green iguana lays only two or three eggs, | 0:20:50 | 0:20:54 | |

burying them with care in the ground. | 0:20:54 | 0:20:58 | |

From all reptile eggs, the young clamber out, fully formed, | 0:21:07 | 0:21:10 | |

virtually exact miniatures of their parents | 0:21:10 | 0:21:13 | |

and ready for immediate action. | 0:21:13 | 0:21:15 | |

These are baby skinks. | 0:21:25 | 0:21:27 | |

From an egg like this | 0:21:34 | 0:21:35 | |

there once hatched one of the most spectacular reptiles of all. | 0:21:35 | 0:21:39 | |

For this is the fossilised egg of a dinosaur. | 0:21:48 | 0:21:52 | |

There can be no question of the success of these early reptiles. | 0:21:52 | 0:21:55 | |

They dominated the world for 130 million years. | 0:21:55 | 0:21:59 | |

During that time, they developed into all kinds of shapes and sizes. | 0:21:59 | 0:22:04 | |

Many took to the air, | 0:22:15 | 0:22:17 | |

and some were the biggest flying animals to have existed, | 0:22:17 | 0:22:21 | |

with a wingspan as big as a small aeroplane. | 0:22:21 | 0:22:25 | |

Others even returned to the sea. | 0:22:29 | 0:22:31 | |

Some rowed themselves along with huge flippers, | 0:22:31 | 0:22:35 | |

while others sculled with their tails as dolphins do today. | 0:22:35 | 0:22:39 | |

And turtles grew to the size of a small boat. | 0:22:41 | 0:22:45 | |

From eggs hatched the dinosaur dynasty, | 0:22:47 | 0:22:50 | |

which was the most spectacular demonstration of reptilian success. | 0:22:50 | 0:22:54 | |

Deinonychus. | 0:22:56 | 0:22:59 | |

Tyrannosaurus rex. | 0:22:59 | 0:23:01 | |

The three-horned dinosaur, triceratops. | 0:23:04 | 0:23:08 | |

Stegosaurus, parasaurolophus. | 0:23:08 | 0:23:11 | |

And brachiosaurus, as big as a house. | 0:23:11 | 0:23:15 | |

These were among the most impressive animals ever to tread the earth. | 0:23:15 | 0:23:18 | |

And we know them from their bones. | 0:23:18 | 0:23:21 | |

This is the richest deposit of dinosaur bones yet discovered. | 0:23:22 | 0:23:27 | |

It's in Utah, in the western United States, | 0:23:27 | 0:23:29 | |

and 140 million years ago, | 0:23:29 | 0:23:32 | |

when the dinosaurs were at their prime, | 0:23:32 | 0:23:35 | |

this great cliff face, which is now tilted, lay horizontally. | 0:23:35 | 0:23:40 | |

This stone was the loose sand and gravel | 0:23:40 | 0:23:43 | |

of a sandbank in the middle of a wide river. | 0:23:43 | 0:23:47 | |

Down that river floated the great, bloated, rotting carcasses | 0:23:47 | 0:23:54 | |

of huge dinosaurs. | 0:23:54 | 0:23:56 | |

And many of them got stranded on this river bank, | 0:23:56 | 0:24:00 | |

and here their bones lie. | 0:24:00 | 0:24:02 | |

The layer in which they lie is only about 12 feet thick. | 0:24:02 | 0:24:07 | |

It's thought it was all laid down in the space of 100 years or so, | 0:24:07 | 0:24:12 | |

which gives some idea of how abundant they must have been at the time. | 0:24:12 | 0:24:16 | |

The long bones - the leg bones and the shoulder blades | 0:24:16 | 0:24:20 | |

and tails and backbones - | 0:24:20 | 0:24:22 | |

are all roughly pointing in this direction. | 0:24:22 | 0:24:26 | |

That makes it pretty clear | 0:24:26 | 0:24:28 | |

that the river current flowed this way. | 0:24:28 | 0:24:31 | |

This is a plate from a young stegosaurus, | 0:24:39 | 0:24:41 | |

the one with two rows of blades on its back. | 0:24:41 | 0:24:43 | |

And this the tooth of a savage allosaurus. | 0:24:47 | 0:24:51 | |

14 different species of dinosaur have been found in this quarry, | 0:24:54 | 0:24:58 | |

ranging from tiny creatures no bigger than a chicken | 0:24:58 | 0:25:03 | |

to real monsters like the animal to whom | 0:25:03 | 0:25:05 | |

this enormous thigh bone belonged, | 0:25:05 | 0:25:08 | |

which was one of the biggest land-living animals | 0:25:08 | 0:25:10 | |

the world has seen. | 0:25:10 | 0:25:12 | |

Most of the bones left in this quarry | 0:25:12 | 0:25:15 | |

come from carcasses dismembered by the river | 0:25:15 | 0:25:19 | |

or by scavenging reptiles, | 0:25:19 | 0:25:21 | |

but by the time quarrying finished here in the 1920s, | 0:25:21 | 0:25:25 | |

over 30 near-complete skeletons had been taken away, | 0:25:25 | 0:25:28 | |

and many of the most beautiful and impressive dinosaur skeletons | 0:25:28 | 0:25:32 | |

in our museums today come from this quarry | 0:25:32 | 0:25:36 | |

or from others working in the same formation. | 0:25:36 | 0:25:39 | |

A brontosaurus, one of the biggest of all. | 0:25:41 | 0:25:45 | |

Over 60 feet long and weighing in life about 30 tons, | 0:25:45 | 0:25:49 | |

about the same as three full-grown bull elephants. | 0:25:49 | 0:25:53 | |

The question immediately arises - | 0:25:53 | 0:25:55 | |

why did these vegetable-eating dinosaurs | 0:25:55 | 0:25:58 | |

grow to such a gigantic size? | 0:25:58 | 0:26:01 | |

There are at least two possible answers. | 0:26:01 | 0:26:04 | |

The first concerns their food, which was cycads and ferns. | 0:26:04 | 0:26:09 | |

Those sort of plants are tough and fibrous | 0:26:09 | 0:26:13 | |

and take a great deal of digestion. | 0:26:13 | 0:26:16 | |

The dinosaurs only had relatively feeble teeth | 0:26:16 | 0:26:18 | |

which weren't much good at mastication, | 0:26:18 | 0:26:20 | |

so they had to have huge stomachs | 0:26:20 | 0:26:23 | |

which would serve as fermentation vats | 0:26:23 | 0:26:27 | |

in which the food could be kept for long periods of time | 0:26:27 | 0:26:30 | |

while it was digested. | 0:26:30 | 0:26:31 | |

A huge stomach requires a huge body to carry it. | 0:26:31 | 0:26:36 | |

The second reason concerns that recurring problem for all reptiles - | 0:26:36 | 0:26:41 | |

temperature control. | 0:26:41 | 0:26:43 | |

The bigger your body, the less susceptible it is | 0:26:43 | 0:26:47 | |

to variations in temperature, because it retains its heat longer. | 0:26:47 | 0:26:52 | |

Temperature control may be the reason | 0:26:52 | 0:26:56 | |

for the bizarre body of another famous dinosaur, | 0:26:56 | 0:27:00 | |

the stegosaurus. | 0:27:00 | 0:27:02 | |

It used to be said that these plates were a kind of armour. | 0:27:02 | 0:27:05 | |

But close examination has shown | 0:27:05 | 0:27:08 | |

that they were covered with a skin thick with blood. | 0:27:08 | 0:27:12 | |

So if the animal were broadside onto the sun, | 0:27:12 | 0:27:15 | |

they would serve as solar panels, rapidly warming the blood. | 0:27:15 | 0:27:19 | |

And if it were overheated and faced into the sun, | 0:27:19 | 0:27:23 | |

they would serve as cooling radiators. | 0:27:23 | 0:27:26 | |

Such an ability to influence temperature | 0:27:26 | 0:27:29 | |

could have been invaluable. | 0:27:29 | 0:27:30 | |

Certainly, for a plant eater to be sluggish on a cool morning | 0:27:30 | 0:27:34 | |

could've been disastrous. | 0:27:34 | 0:27:36 | |

Down in Texas, the muds of an estuary, | 0:27:48 | 0:27:51 | |

now turned to rock and forming a river bed, | 0:27:51 | 0:27:54 | |

preserve a vivid record of these creatures. | 0:27:54 | 0:27:57 | |

This is the footprint of a flesh-eating dinosaur, a hunter, | 0:28:00 | 0:28:04 | |

with huge talons on its two feet. | 0:28:04 | 0:28:07 | |

It stood on its two feet, upright, about 10 or 12 feet tall, | 0:28:07 | 0:28:13 | |

with its tail on the ground, which here has ploughed into the mud, | 0:28:13 | 0:28:17 | |

throwing up this great furrow. | 0:28:17 | 0:28:20 | |

Here are two more of them. | 0:28:20 | 0:28:23 | |

From their depth, we can get an idea of the animal's great weight. | 0:28:23 | 0:28:27 | |

The line of tracks continues across the rock of the river bed. | 0:28:30 | 0:28:35 | |

Further down are the tracks of the reptile | 0:28:40 | 0:28:42 | |

it may well have been stalking, | 0:28:42 | 0:28:44 | |

one of those huge vegetarians, with footprints a yard across. | 0:28:44 | 0:28:49 | |

Farther north, in the badlands of Montana, | 0:28:52 | 0:28:55 | |

the muds and sands over which the dinosaurs roamed | 0:28:55 | 0:28:58 | |

form cliffs of crumbling rocks. | 0:28:58 | 0:29:01 | |

And here, weathering out near the top of this cliff, | 0:29:08 | 0:29:13 | |

is the skull of one of the most dramatic of all dinosaurs - | 0:29:13 | 0:29:18 | |

triceratops, the three-horned dinosaur. | 0:29:18 | 0:29:21 | |

Here's one horn. Here's the second horn, | 0:29:21 | 0:29:23 | |

which has already weathered away. | 0:29:23 | 0:29:25 | |

And its nose is pointing that way, | 0:29:25 | 0:29:27 | |

so its third horn on the tip of the nose is still in this rock. | 0:29:27 | 0:29:33 | |

Here is its eye. It has this great bony frill extending over its neck. | 0:29:33 | 0:29:38 | |

In life, it was an immense creature, weighing eight to ten tons, | 0:29:38 | 0:29:44 | |

20 or 30 feet long. | 0:29:44 | 0:29:46 | |

It was a vegetarian, champing up with powerful, scissor-like jaws | 0:29:46 | 0:29:51 | |

the cycads that grew in this neighbourhood. | 0:29:51 | 0:29:55 | |

And this head alone weighed about two tons. | 0:29:55 | 0:30:00 | |

The bony frill, while doubtless protecting the neck, | 0:30:00 | 0:30:03 | |

also carried a great band of muscles, | 0:30:03 | 0:30:07 | |

helping to manipulate and move this heavy head. | 0:30:07 | 0:30:11 | |

Its brain was comparatively large, | 0:30:11 | 0:30:13 | |

one of the largest of all dinosaurs' brains, | 0:30:13 | 0:30:17 | |

weighing about two pounds, but that didn't save it. | 0:30:17 | 0:30:21 | |

This beast was one of the last of its kind. | 0:30:21 | 0:30:24 | |

On a geological timescale, | 0:30:26 | 0:30:28 | |

the disappearance of the dinosaurs was extraordinarily abrupt. | 0:30:28 | 0:30:32 | |

It's marked in the most dramatic way in these cliffs. | 0:30:32 | 0:30:36 | |

Among the yellow and red sandstones and clays, | 0:30:36 | 0:30:40 | |

there is this thin layer of coal along which I'm walking. | 0:30:40 | 0:30:44 | |

Its black line rules an end to the reign of the dinosaurs. | 0:30:44 | 0:30:48 | |

In the beds beneath it, there have been found in this area | 0:30:48 | 0:30:52 | |

the remains of at least nine or ten different species of dinosaur. | 0:30:52 | 0:30:57 | |

Above it, there are none. | 0:30:57 | 0:31:00 | |

Even though the end may have taken | 0:31:00 | 0:31:02 | |

tens of thousands of years to be complete, | 0:31:02 | 0:31:05 | |

it was nonetheless extraordinarily abrupt and wholesale. | 0:31:05 | 0:31:09 | |

What on earth could have brought it about? | 0:31:10 | 0:31:12 | |

There have been dozens of suggestions. | 0:31:15 | 0:31:17 | |

The more extreme require some kind of global catastrophe, | 0:31:17 | 0:31:22 | |

but they're unlikely to be correct | 0:31:22 | 0:31:24 | |

because it was only the dinosaurs that disappeared, not all reptiles. | 0:31:24 | 0:31:28 | |

A more reasonable idea is that | 0:31:28 | 0:31:30 | |

it was the rise of the warm-blooded furry mammals | 0:31:30 | 0:31:34 | |

that caused the disappearance of the dinosaurs. | 0:31:34 | 0:31:37 | |

We can test the likelihood of that theory | 0:31:37 | 0:31:40 | |

by looking at the anthills around here. | 0:31:40 | 0:31:43 | |

The ants in this part of the world roof their nests with gravel. | 0:31:48 | 0:31:52 | |

Amongst the chips of stone they laboriously haul here | 0:31:52 | 0:31:57 | |

are things like this. | 0:31:57 | 0:32:00 | |

This is the tooth of a tiny mammal. | 0:32:01 | 0:32:05 | |

A small, shrew-like creature, and that was the largest mammal | 0:32:05 | 0:32:10 | |

that existed in this dinosaur-dominated part of the world. | 0:32:10 | 0:32:14 | |

It's inconceivable that such tiny creatures | 0:32:14 | 0:32:17 | |

could have offered any competition with the dinosaurs. | 0:32:17 | 0:32:21 | |

No, there are better answers to the problem than that. | 0:32:21 | 0:32:25 | |

The America across which the dinosaurs roamed | 0:32:39 | 0:32:42 | |

was covered with thick jungle. | 0:32:42 | 0:32:44 | |

But this fossilised tree, | 0:32:44 | 0:32:46 | |

which was alive just after the last dinosaurs disappeared, | 0:32:46 | 0:32:50 | |

is not of a jungle tree. | 0:32:50 | 0:32:52 | |

This is a redwood, a sequoia, | 0:32:52 | 0:32:54 | |

a tree which now, and almost certainly then, | 0:32:54 | 0:32:57 | |

preferred a cool climate, | 0:32:57 | 0:32:59 | |

and it's just one piece of a body of evidence we have | 0:32:59 | 0:33:02 | |

which goes to show that about 63 million years ago, | 0:33:02 | 0:33:06 | |

almost simultaneous with the disappearance of the dinosaurs, | 0:33:06 | 0:33:10 | |

the world went through a great climate change. | 0:33:10 | 0:33:13 | |

It got colder. | 0:33:13 | 0:33:15 | |

In a cold climate, | 0:33:15 | 0:33:17 | |

the absence of a good insulating skin could be lethal. | 0:33:17 | 0:33:22 | |

While it's true that a big body retains heat for a long time, | 0:33:22 | 0:33:25 | |

it's also true that such a body | 0:33:25 | 0:33:27 | |

takes a long time to regain it once it's been lost. | 0:33:27 | 0:33:31 | |

And so it could be that a succession of cold nights | 0:33:31 | 0:33:36 | |

would be enough to drain a dinosaur of its heat beyond recovery. | 0:33:36 | 0:33:40 | |

And so, such a cooling of the climate might, over thousands of years, | 0:33:40 | 0:33:46 | |

be enough to exterminate the entire race of dinosaurs. | 0:33:46 | 0:33:49 | |

But of course the effect of cold nights | 0:33:49 | 0:33:52 | |

is much less on animals that live in the water. | 0:33:52 | 0:33:55 | |

Water retains heat longer than the air. | 0:33:55 | 0:33:59 | |

Indeed, there are giant water-living reptiles | 0:33:59 | 0:34:03 | |

that have survived from the age of the dinosaur | 0:34:03 | 0:34:06 | |

right until today. | 0:34:06 | 0:34:07 | |

This is a truly primeval scene. | 0:34:31 | 0:34:34 | |

Crocodiles have been lazing around swamps like this | 0:34:44 | 0:34:48 | |

since the beginning of the age of the dinosaurs. | 0:34:48 | 0:34:52 | |

At seven metres long and weighing three quarters of a ton, | 0:34:52 | 0:34:55 | |

a bull Nile crocodile is the biggest reptile alive today. | 0:34:55 | 0:34:59 | |

It's thought that reptiles in general and dinosaurs in particular | 0:35:11 | 0:35:16 | |

were dull, stupid creatures with only glimmerings of intelligence | 0:35:16 | 0:35:20 | |

and the simplest of behaviour patterns. | 0:35:20 | 0:35:23 | |

That's a very mistaken view, | 0:35:23 | 0:35:25 | |

as recent discoveries about the behaviour of crocodiles have shown. | 0:35:25 | 0:35:29 | |

Since water holds the heat, | 0:35:29 | 0:35:30 | |

crocodiles spend the cool nights in the river. | 0:35:30 | 0:35:33 | |

To them, it's like a warm bath. | 0:35:33 | 0:35:36 | |

But as the sun rises, they emerge | 0:35:36 | 0:35:38 | |

to boost their body temperatures in the sun. | 0:35:38 | 0:35:42 | |

To prevent themselves from overheating, | 0:36:01 | 0:36:03 | |

they use one trick marine iguanas don't have. | 0:36:03 | 0:36:06 | |

They gape. | 0:36:06 | 0:36:08 | |

Their mouth is lined with thinner skin | 0:36:27 | 0:36:30 | |

than the armoured hide on their body, | 0:36:30 | 0:36:32 | |

so the blood in the capillaries there is more quickly cooled. | 0:36:32 | 0:36:36 | |

When, with the sun's help, their bodies are warmed up, | 0:36:42 | 0:36:46 | |

they can move very fast indeed. | 0:36:46 | 0:36:48 | |

They don't have lips so their mouths are not watertight. | 0:36:56 | 0:37:00 | |

If they were to swallow when submerged, | 0:37:00 | 0:37:02 | |

water would flood down their throats. | 0:37:02 | 0:37:04 | |

So eating and swallowing has to be done above the surface. | 0:37:04 | 0:37:09 | |

The surprising complexity of their family life | 0:37:09 | 0:37:13 | |

may indicate how dinosaurs behaved. | 0:37:13 | 0:37:16 | |

Crocodiles mate in the water. | 0:37:16 | 0:37:18 | |

The 40 or so eggs are laid in a hole on the river bank | 0:37:18 | 0:37:22 | |

and covered with sand. | 0:37:22 | 0:37:24 | |

Though the parents don't incubate the eggs, they usually remain close by. | 0:37:26 | 0:37:30 | |

After about 90 days, when the eggs are about to hatch, | 0:37:30 | 0:37:34 | |

the young, buried and still in their shells, begin calling, | 0:37:34 | 0:37:38 | |

and the female starts to dig them up. | 0:37:38 | 0:37:41 | |

CHIRPING | 0:37:41 | 0:37:44 | |

Then a very remarkable thing happens. | 0:37:45 | 0:37:49 | |

At this time, the mother develops a pouch beneath her chin | 0:37:49 | 0:37:53 | |

which will hold about seven eggs or young. | 0:37:53 | 0:37:55 | |

The eggs are about to hatch, | 0:38:11 | 0:38:13 | |

as she knows from the chirps of the young inside them. | 0:38:13 | 0:38:16 | |

She's taking them off to a nursery area in another part of the swamp, | 0:38:31 | 0:38:36 | |

where there's better cover | 0:38:36 | 0:38:37 | |

than beside the sandy bank where she nests. | 0:38:37 | 0:38:40 | |

Burying eggs has its drawbacks. They can become damp and chilled. | 0:38:59 | 0:39:04 | |

Nearby, there's another nest from which no young emerged. | 0:39:04 | 0:39:08 | |

When the parents weren't looking, a predator dug them up and ate them. | 0:39:08 | 0:39:12 | |

Now the remains are only food for ants and beetles. | 0:39:12 | 0:39:16 | |

This is the culprit. A monitor lizard. | 0:39:26 | 0:39:28 | |

It will take babies as eagerly as eggs. | 0:39:28 | 0:39:31 | |

With predators like this around, | 0:39:31 | 0:39:33 | |

it pays crocodiles to guard their clutch. | 0:39:33 | 0:39:35 | |

The mother returns in the nick of time. | 0:39:43 | 0:39:47 | |

It's tempting to think the great dinosaurs | 0:40:17 | 0:40:20 | |

may have cared just as delicately for their babies. | 0:40:20 | 0:40:24 | |

Even the bull responds to the sight and sounds of the young. | 0:40:45 | 0:40:50 | |

Like all reptile hatchlings, | 0:41:54 | 0:41:55 | |

the young are miniature versions of the adults | 0:41:55 | 0:41:58 | |

and capable of finding food for themselves | 0:41:58 | 0:42:00 | |

from the moment they leave the shell. | 0:42:00 | 0:42:02 | |

The babies could be a meal for birds or other crocodiles, | 0:42:39 | 0:42:43 | |

so the parents watch over them while they perfect their hunting skills. | 0:42:43 | 0:42:48 | |

Crocodiles, together with tortoises, | 0:42:51 | 0:42:53 | |

have changed little over the past ages. | 0:42:53 | 0:42:55 | |

The ancestral reptiles were walkers. | 0:42:55 | 0:42:58 | |

But the most sophisticated of modern forms | 0:42:58 | 0:43:01 | |

have changed their style of getting around. | 0:43:01 | 0:43:04 | |

It all started with lizards. They too are an ancient group, | 0:43:17 | 0:43:21 | |

but early in their history, they gave rise to a successful family. | 0:43:21 | 0:43:26 | |

The lizards, for some reason, have a tendency to lose legs. | 0:43:26 | 0:43:30 | |

Some are still in the process of doing so today, | 0:43:30 | 0:43:33 | |

and live under rocks or burrow, | 0:43:33 | 0:43:35 | |

where legs could get in the way. | 0:43:35 | 0:43:38 | |

The Australian blue-tongued skink has very small legs. | 0:43:38 | 0:43:42 | |

In this South African skink, they've virtually disappeared. | 0:43:42 | 0:43:46 | |

And it moves by wriggling. | 0:43:48 | 0:43:51 | |

The Australian scaly foot, as its name suggests, | 0:43:56 | 0:44:00 | |

has only a pair of stumps at the rear | 0:44:00 | 0:44:02 | |

to betray the fact it's a burrowing lizard. | 0:44:02 | 0:44:05 | |

This grotesque creature | 0:44:10 | 0:44:12 | |

has all but lost its eyes as well as its legs. | 0:44:12 | 0:44:15 | |

It's an amphisbaenid and normally lives entirely underground. | 0:44:15 | 0:44:19 | |

Some 100 million years ago, | 0:44:22 | 0:44:23 | |

another group of lizards also took to burrowing | 0:44:23 | 0:44:26 | |

and they lost their legs. | 0:44:26 | 0:44:28 | |

Some of their descendants came back above ground | 0:44:28 | 0:44:31 | |

and became snakes. | 0:44:31 | 0:44:32 | |

Pythons and boas still retain evidence that they once had limbs - | 0:44:34 | 0:44:37 | |

two tiny spurs where their hind legs once were. | 0:44:37 | 0:44:41 | |

Without legs, the snakes had to develop techniques | 0:44:41 | 0:44:44 | |

for getting around. | 0:44:44 | 0:44:45 | |

And very efficient they are, too. | 0:44:45 | 0:44:48 | |

The boa's regular method is to throw its body into S-shaped coils | 0:44:50 | 0:44:55 | |

so its flanks get purchase on irregularities on the surface | 0:44:55 | 0:44:59 | |

and the scales underneath grip the ground. | 0:44:59 | 0:45:01 | |

As the coils move backwards, the snake can thrust itself forwards. | 0:45:01 | 0:45:06 | |

Boas, like most snakes, can also move in a straight line | 0:45:08 | 0:45:11 | |

by shuffling along on their ribs. | 0:45:11 | 0:45:13 | |

That's useful for crawling along a branch. | 0:45:13 | 0:45:16 | |

The puff adder, when stalking prey, also moves on its ribs, | 0:45:18 | 0:45:23 | |

lifting them in groups and pulling the scales of its underside | 0:45:23 | 0:45:27 | |

forward and over the rib tips | 0:45:27 | 0:45:28 | |

so undulations pass down the lower half of the body. | 0:45:28 | 0:45:32 | |

To me, the most mystifying technique | 0:45:33 | 0:45:35 | |

is that used by the sidewinder in south-west Africa. | 0:45:35 | 0:45:39 | |

The key to understanding how it works | 0:46:18 | 0:46:20 | |

is to watch for the only two places where, | 0:46:20 | 0:46:23 | |

at any one time, its body touches the ground. | 0:46:23 | 0:46:25 | |

It is taking a series of steps sideways. | 0:46:25 | 0:46:30 | |

With only two points of contact, the hot sand doesn't burn it. | 0:46:30 | 0:46:35 | |

With such methods of stalking prey, | 0:46:38 | 0:46:41 | |

the snakes have become formidable hunters. | 0:46:41 | 0:46:44 | |

Many snakes have become swimmers and hunt underwater. | 0:46:48 | 0:46:52 | |

This venomous Florida mud snake | 0:46:54 | 0:46:56 | |

has caught a siren, a sort of amphibian. | 0:46:56 | 0:46:59 | |

Some are prepared to catch the most spiky of meals | 0:46:59 | 0:47:03 | |

and subdue them by throwing coils around them. | 0:47:03 | 0:47:05 | |

This might seem an impossible mouthful. | 0:47:09 | 0:47:12 | |

Most snakes have jaws hinged to give them a great gape, | 0:47:12 | 0:47:16 | |

but that of the egg-eating snake is simply vast. | 0:47:16 | 0:47:20 | |

Once swallowed, it cracks the egg | 0:47:51 | 0:47:54 | |

by grinding it against spikes that project into the gut. | 0:47:54 | 0:47:58 | |

In many parts of the world, snakes flourish in huge numbers. | 0:48:03 | 0:48:07 | |

They're so unobtrusive, | 0:48:07 | 0:48:09 | |

it's difficult to appreciate how many there are, | 0:48:09 | 0:48:12 | |

except on special occasions. | 0:48:12 | 0:48:14 | |

One such occurs every spring in southern Canada. | 0:48:14 | 0:48:18 | |

Prairie garter snakes hibernate communally. | 0:48:18 | 0:48:21 | |

When spring comes, a flood of newly-warm snakes | 0:48:21 | 0:48:25 | |

spills from the limestone pits where they've wintered. | 0:48:25 | 0:48:28 | |

As soon as they emerge, they mate, and in the most spectacular fashion. | 0:48:28 | 0:48:33 | |

Each female leaves a trail of sexual scent, | 0:48:35 | 0:48:38 | |

which attracts up to 100 of the smaller males, | 0:48:38 | 0:48:42 | |

which frantically struggle to become her mate. | 0:48:42 | 0:48:45 | |

These garter snakes are very advanced members of their group. | 0:49:25 | 0:49:29 | |

Not only have they developed the technique of hibernation | 0:49:29 | 0:49:32 | |

to live through the winters when the ground is covered in snow, | 0:49:32 | 0:49:36 | |

but they've managed to overcome | 0:49:36 | 0:49:38 | |

many of the limitations of egg-laying. | 0:49:38 | 0:49:41 | |

A few months after this communal mating, the offspring appear. | 0:49:41 | 0:49:45 | |

Instead of laying and abandoning her eggs as most snakes do, | 0:49:58 | 0:50:01 | |

the female garter snake becomes a mobile incubator. | 0:50:01 | 0:50:05 | |

She retains her batch of eggs inside her body, | 0:50:05 | 0:50:08 | |

thereby protecting them. | 0:50:08 | 0:50:10 | |

By basking in the sun, she keeps them warm. | 0:50:10 | 0:50:13 | |

She even contributes to the nourishment of the embryos | 0:50:13 | 0:50:17 | |

over three months, almost like mammals do, | 0:50:17 | 0:50:20 | |

until the time comes for them to be born. | 0:50:20 | 0:50:23 | |

Live bearing is practised by several snakes, | 0:50:56 | 0:50:59 | |

including some that have a claim | 0:50:59 | 0:51:01 | |

to be the most highly-evolved reptiles of all. | 0:51:01 | 0:51:05 | |

You can find them in the deserts of the western United States. | 0:51:05 | 0:51:09 | |

RATTLING | 0:51:13 | 0:51:14 | |

Rattlesnakes. | 0:51:14 | 0:51:16 | |

This is the western diamondback. | 0:51:16 | 0:51:19 | |

No animal alive can excel these creatures | 0:51:19 | 0:51:21 | |

when it comes to finding, stalking and dispatching their victims. | 0:51:21 | 0:51:27 | |

Its scales serve it in several ways. | 0:51:33 | 0:51:36 | |

Those on its flanks are grooved | 0:51:36 | 0:51:38 | |

to increase efficiency as heat absorbers. | 0:51:38 | 0:51:40 | |

Those on its tail are hollow rattles. | 0:51:47 | 0:51:50 | |

A pit beneath its eye is so sensitive to heat | 0:51:57 | 0:52:01 | |

that it can detect the body warmth of a small mammal half a metre away. | 0:52:01 | 0:52:05 | |

The snake's flickering tongue tastes the air. | 0:52:08 | 0:52:12 | |

This is a Mexican blacktail rattlesnake. | 0:52:12 | 0:52:14 | |

It collects the smell as molecules in the air | 0:52:19 | 0:52:23 | |

and then carries them back to a pit | 0:52:23 | 0:52:25 | |

in the top of its mouth for tasting. | 0:52:25 | 0:52:28 | |

When it's found its prey, it strikes. | 0:52:37 | 0:52:41 | |

The huge poisoned fangs hinge forward, | 0:52:41 | 0:52:44 | |

ready to inject one of the most lethal poisons in the world. | 0:52:44 | 0:52:47 | |

A rattlesnake can survive here | 0:53:02 | 0:53:04 | |

on only a dozen or so meals in a year. | 0:53:04 | 0:53:07 | |

And that's pretty efficient. | 0:53:07 | 0:53:10 | |

But being cold-blooded, solar-powered, | 0:53:10 | 0:53:13 | |

does have its limitations. | 0:53:13 | 0:53:15 | |

No reptile can survive sustained cold, | 0:53:15 | 0:53:19 | |

so great areas of the world are closed to them. | 0:53:19 | 0:53:23 | |

But a very long time ago, one group of the reptiles | 0:53:23 | 0:53:26 | |

evolved an answer to that problem. | 0:53:26 | 0:53:28 | |

An answer that was based on that versatile thing, | 0:53:28 | 0:53:32 | |

the reptilian scale. | 0:53:32 | 0:53:34 | |

A feather. | 0:53:36 | 0:53:37 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:54:24 | 0:54:27 |