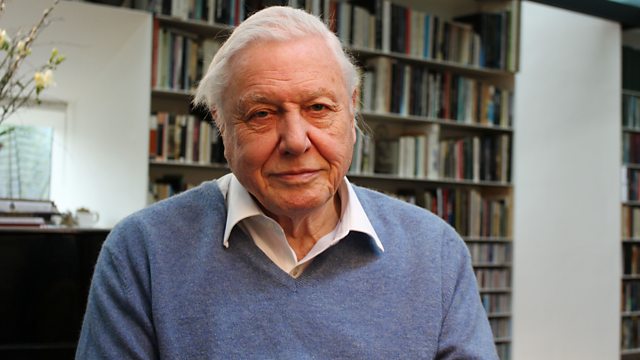

Episode 1 David Attenborough's Natural Curiosities

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Episode 1. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

The natural world is full of extraordinary animals | 0:00:02 | 0:00:06 | |

with amazing life histories. | 0:00:06 | 0:00:08 | |

Yet certain stories are more intriguing than most. | 0:00:08 | 0:00:13 | |

The mysteries of a butterfly's life cycle | 0:00:15 | 0:00:19 | |

or the strange biology of the Emperor Penguin. | 0:00:19 | 0:00:22 | |

Some of these creatures were surrounded | 0:00:22 | 0:00:26 | |

by myth and misunderstandings for a very long time, | 0:00:26 | 0:00:30 | |

and some have only recently revealed their secrets. | 0:00:30 | 0:00:33 | |

These are the animals that stand out from the crowd, | 0:00:35 | 0:00:38 | |

the curiosities I find most fascinating of all. | 0:00:38 | 0:00:43 | |

In this programme, I investigate creatures | 0:00:50 | 0:00:53 | |

that have taken the ordinary and made it extraordinary. | 0:00:53 | 0:00:57 | |

The chameleon that has an extra long tongue to catch prey... | 0:00:57 | 0:01:01 | |

..and the giraffe with a neck so long it can reach the top of trees. | 0:01:02 | 0:01:07 | |

How and why have these animals stretched nature to the limit? | 0:01:08 | 0:01:13 | |

And also in this programme, | 0:01:13 | 0:01:15 | |

we explore the stories of two animals | 0:01:15 | 0:01:17 | |

that sent shock waves through the scientific world and beyond. | 0:01:17 | 0:01:22 | |

One is a toad that became the centre of a scientific storm | 0:01:22 | 0:01:26 | |

and caused accusations of fakery in the early part of the 20th century. | 0:01:26 | 0:01:31 | |

The other is an Australian animal | 0:01:33 | 0:01:35 | |

that baffled the greatest thinkers of Victorian Europe | 0:01:35 | 0:01:38 | |

and caused many to question whether it was even real. | 0:01:38 | 0:01:42 | |

The chameleon is a truly bizarre creature, | 0:01:57 | 0:02:01 | |

both in its behaviour and its appearance | 0:02:01 | 0:02:04 | |

unlike anything else on earth. | 0:02:04 | 0:02:06 | |

So, not surprisingly, it's given rise to all kinds of legends and myths, | 0:02:06 | 0:02:11 | |

This is The History Of The Four-footed Beasts by Edward Topsell | 0:02:11 | 0:02:15 | |

written in the 17th century. | 0:02:15 | 0:02:18 | |

And he calls the chameleon, | 0:02:18 | 0:02:20 | |

"A fraudulent, ravening and gluttonous beast, | 0:02:20 | 0:02:23 | |

"impure and unclean by the law of God." | 0:02:23 | 0:02:27 | |

Some believed it was constructed by the devil | 0:02:27 | 0:02:31 | |

from parts of other animals, | 0:02:31 | 0:02:33 | |

the tail of a monkey, the skin of a crocodile, | 0:02:33 | 0:02:36 | |

the tongue of a toad, the horns of a rhinoceros, | 0:02:36 | 0:02:40 | |

and the eyes of who knows what. | 0:02:40 | 0:02:42 | |

It was a creature sent to the world to spy for a demon master. | 0:02:42 | 0:02:47 | |

When I first came face to face with the chameleon more than 50 years ago, | 0:02:49 | 0:02:53 | |

I was struck not only by its beauty, | 0:02:53 | 0:02:56 | |

but intrigued by its strange body, particularly by its tongue. | 0:02:56 | 0:03:01 | |

The outlandish appearance of the chameleon | 0:03:04 | 0:03:07 | |

made it much sought-after by curiosity hunters, | 0:03:07 | 0:03:10 | |

but scientists and naturalists too were greatly puzzled | 0:03:10 | 0:03:14 | |

by its extraordinary behaviour and anatomy. | 0:03:14 | 0:03:18 | |

It looked and behaved like no other reptile. | 0:03:20 | 0:03:23 | |

Even today, we're still discovering new things about its unique eyes, | 0:03:25 | 0:03:30 | |

its astonishing tongue, | 0:03:30 | 0:03:33 | |

and its ability to change its appearance. | 0:03:33 | 0:03:36 | |

Chameleons are notoriously hard to find, | 0:03:40 | 0:03:43 | |

partly because they move so slowly, | 0:03:43 | 0:03:45 | |

but also because they match their surroundings | 0:03:45 | 0:03:48 | |

in terms of colour so very well. | 0:03:48 | 0:03:51 | |

This one in front of me is a dwarf chameleon | 0:03:51 | 0:03:54 | |

from Natal in South Africa. | 0:03:54 | 0:03:57 | |

If that's threatened by a snake, | 0:03:57 | 0:03:59 | |

it doesn't bother to change its colour very much, | 0:03:59 | 0:04:01 | |

because a snake's colour vision is not very good, | 0:04:01 | 0:04:04 | |

but if it's threatened by a bird, | 0:04:04 | 0:04:07 | |

it does camouflage itself very well indeed. | 0:04:07 | 0:04:10 | |

Some species of chameleon, | 0:04:13 | 0:04:14 | |

and there are 85 different species in the family, | 0:04:14 | 0:04:18 | |

can even fine tune their camouflage. | 0:04:18 | 0:04:20 | |

If they detect a snake approaching from below, | 0:04:23 | 0:04:25 | |

they become lighter in colour and so less noticeable against the sky. | 0:04:25 | 0:04:30 | |

On the other hand, if the threat comes from a bird, | 0:04:32 | 0:04:35 | |

they become darker to match the background beneath them. | 0:04:35 | 0:04:38 | |

A chameleon's colour is affected not only by its surroundings, | 0:04:40 | 0:04:45 | |

but by the temperature and the light and its emotional state. | 0:04:45 | 0:04:49 | |

Behind this screen there's a rival male. | 0:04:49 | 0:04:53 | |

Let's see what happens if I remove the screen | 0:04:53 | 0:04:56 | |

and let them see one another. | 0:04:56 | 0:04:58 | |

This highly-coloured male is dominant | 0:05:00 | 0:05:02 | |

and he immediately adds bright, aggressive colours to his display. | 0:05:02 | 0:05:07 | |

The other male remains dark | 0:05:07 | 0:05:09 | |

and too frightened to change colour and fight back. | 0:05:09 | 0:05:12 | |

It's clear who's the boss. | 0:05:12 | 0:05:15 | |

Chameleons are emotional creatures, | 0:05:20 | 0:05:23 | |

darker colouration signals anger. | 0:05:23 | 0:05:25 | |

This female on the right is not in the mood | 0:05:25 | 0:05:28 | |

to accept the approaches of this brightly coloured and hopeful male. | 0:05:28 | 0:05:32 | |

Exactly how chameleons achieve such dramatic colour changes | 0:05:41 | 0:05:44 | |

greatly puzzled early naturalists. | 0:05:44 | 0:05:47 | |

An Englishman named Barrow, | 0:05:49 | 0:05:51 | |

who travelled in Africa in the 19th century, | 0:05:51 | 0:05:53 | |

thought the changing colour was caused by something to do with air. | 0:05:53 | 0:05:57 | |

He wrote, "Previous to the chameleon assuming a change in colour, | 0:05:57 | 0:06:02 | |

"it makes a long inspiration, | 0:06:02 | 0:06:04 | |

"the body swelling out to twice its usual size, | 0:06:04 | 0:06:07 | |

"and as this inflation subsides | 0:06:07 | 0:06:10 | |

"the change of colour gradually takes place." | 0:06:10 | 0:06:12 | |

Well, that's an accurate observation of what happens | 0:06:12 | 0:06:16 | |

when a chameleon gets angry and then it's anger subsides, | 0:06:16 | 0:06:20 | |

but actually the change of colour has nothing to do with air. | 0:06:20 | 0:06:24 | |

A French biologist, Mel Edwards, soon after that got it about right. | 0:06:24 | 0:06:29 | |

He wrote, "There exist two layers of membranous pigment | 0:06:29 | 0:06:34 | |

"placed one above the other, | 0:06:34 | 0:06:36 | |

"but disposed in such a way to appear simultaneously under the cuticle | 0:06:36 | 0:06:41 | |

"and sometimes in such a manner that one may hide the other." | 0:06:41 | 0:06:45 | |

Which is indeed so. | 0:06:45 | 0:06:47 | |

Today, we know that the chameleon's skin has three layers | 0:06:49 | 0:06:53 | |

of expendable pigmented cells called chromatophores. | 0:06:53 | 0:06:58 | |

They contain red, yellow, blue and white pigments | 0:06:58 | 0:07:01 | |

with a deeper layer of darker melanin, | 0:07:01 | 0:07:04 | |

which controls the reflection of light. | 0:07:04 | 0:07:07 | |

The chameleons use colour change not only to camouflage themselves, | 0:07:08 | 0:07:13 | |

but also to communicate with one another. | 0:07:13 | 0:07:17 | |

Anyone who looks closely at a chameleon | 0:07:18 | 0:07:22 | |

is bound to be fascinated by its eyes. | 0:07:22 | 0:07:26 | |

They protrude on either side of its head | 0:07:26 | 0:07:30 | |

as though they were mounted on turrets. | 0:07:30 | 0:07:32 | |

And, in fact, their eyelids are fused together | 0:07:32 | 0:07:37 | |

except for one tiny spot right in the middle. | 0:07:37 | 0:07:42 | |

But the most extraordinary thing about them... | 0:07:42 | 0:07:45 | |

is that they move independently. | 0:07:45 | 0:07:47 | |

So that means the chameleon at one and the same time | 0:07:47 | 0:07:52 | |

can be viewing above it and below it. | 0:07:52 | 0:07:55 | |

So any insect that lands nearby | 0:07:55 | 0:07:58 | |

is going to be spotted almost immediately. | 0:07:58 | 0:08:01 | |

It seems that its brain receives separate messages from each eye | 0:08:03 | 0:08:10 | |

and views them and receives them alternately very fast | 0:08:10 | 0:08:14 | |

but independent of one another, they're not integrated. | 0:08:14 | 0:08:19 | |

But the advantage of that is that it does give this | 0:08:19 | 0:08:22 | |

all-round, three-dimensional view | 0:08:22 | 0:08:26 | |

which is unrivalled. | 0:08:26 | 0:08:27 | |

This extraordinary vision is an essential element | 0:08:30 | 0:08:34 | |

in the way the chameleon uses its most astonishing feature, | 0:08:34 | 0:08:38 | |

it's hugely elongated tongue. | 0:08:38 | 0:08:41 | |

How this tongue worked and its construction | 0:08:41 | 0:08:45 | |

greatly intrigued early naturalists - and understandably. | 0:08:45 | 0:08:49 | |

This remarkable preserved specimen shows us in detail | 0:08:56 | 0:08:59 | |

the impressive elongated tongue of a chameleon. | 0:08:59 | 0:09:03 | |

The physical structure of the chameleon's tongue | 0:09:03 | 0:09:07 | |

was easy enough to explain, | 0:09:07 | 0:09:09 | |

although it proved to be a somewhat complicated organ, | 0:09:09 | 0:09:12 | |

a hollow tube with a tapered cartilaginous rod at its base. | 0:09:12 | 0:09:17 | |

The pad at the end was thought to be rough and sticky, | 0:09:17 | 0:09:22 | |

so that it could snag its prey. | 0:09:22 | 0:09:24 | |

But the mystery of how a contraption like this | 0:09:24 | 0:09:28 | |

could be lengthened and projected out of the mouth | 0:09:28 | 0:09:31 | |

took a little longer to fully explain. | 0:09:31 | 0:09:34 | |

Perhaps the way a frigatebird inflates the balloon under its beak, | 0:09:34 | 0:09:38 | |

or how a calling frog blows up its throat sac could give clues, | 0:09:38 | 0:09:43 | |

both do it with air. | 0:09:43 | 0:09:45 | |

Or maybe the tentacles that carry a snail's eye, | 0:09:45 | 0:09:48 | |

it projects them by using its blood as an hydraulic fluid. | 0:09:48 | 0:09:53 | |

But none of them fitted the bill. | 0:09:53 | 0:09:56 | |

It's a much more complex process. | 0:09:57 | 0:10:00 | |

The tongue is a muscular tube | 0:10:00 | 0:10:03 | |

that when relaxed sits on a rod of cartilage. | 0:10:03 | 0:10:06 | |

When the chameleon is ready to strike, | 0:10:06 | 0:10:09 | |

muscles at the back of the tongue push it into launch position. | 0:10:09 | 0:10:13 | |

When the prey is lined up and the distance calculated, | 0:10:13 | 0:10:16 | |

superfast muscles contract | 0:10:16 | 0:10:18 | |

and propel the tongue forward at lightning speed. | 0:10:18 | 0:10:22 | |

As the tongue shoots off the end of the cartilage, | 0:10:24 | 0:10:28 | |

an extra wave of energy drives it forward to its target. | 0:10:28 | 0:10:32 | |

Then, like a stretched elastic band, | 0:10:33 | 0:10:36 | |

its elasticity pulls it back into the chameleon's mouth. | 0:10:36 | 0:10:40 | |

Recently, high-speed images revealed a new detail. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:51 | |

The tip of the tongue, once thought to be sticky, | 0:10:51 | 0:10:54 | |

is covered in microscopic protrusions | 0:10:54 | 0:10:57 | |

that generate suction and secures its prey. | 0:10:57 | 0:11:01 | |

Chameleons really are the most extraordinary creatures | 0:11:07 | 0:11:11 | |

and they hold surprises for us even today. | 0:11:11 | 0:11:15 | |

Only this year, a scientist working in Madagascar | 0:11:15 | 0:11:18 | |

discovered a tiny little chameleon only 29mm long. | 0:11:18 | 0:11:23 | |

It's the smallest known vertebrate in the world. | 0:11:23 | 0:11:28 | |

It's astounding to realise that all the organs of a vertebrate's body | 0:11:28 | 0:11:33 | |

could be fitted into such a tiny little creature, | 0:11:33 | 0:11:37 | |

including that extraordinary tongue. | 0:11:37 | 0:11:40 | |

Next, is the story of another amazing elongated structure, | 0:11:42 | 0:11:47 | |

not a tongue but a neck. | 0:11:47 | 0:11:51 | |

The giraffe is an animal that can't fail to impress. | 0:11:54 | 0:11:58 | |

Up to 6m or 19ft in height, | 0:11:58 | 0:12:01 | |

it's hugely imposing, intriguing in appearance, | 0:12:01 | 0:12:05 | |

and mysterious in its biology. | 0:12:05 | 0:12:08 | |

Our attraction to this unusual creatures goes back centuries. | 0:12:08 | 0:12:12 | |

And one feature in particular has piqued our curiosity - | 0:12:12 | 0:12:15 | |

its elongated neck. | 0:12:15 | 0:12:17 | |

Such a structure seemed an impossibility of nature, | 0:12:17 | 0:12:21 | |

but now we better understand the complex biology | 0:12:21 | 0:12:25 | |

behind the giraffe's bizarre body. | 0:12:25 | 0:12:28 | |

Our growing knowledge of this creature | 0:12:28 | 0:12:30 | |

can be traced back to three very special giraffes | 0:12:30 | 0:12:34 | |

and the story of a royal fascination for the exotic. | 0:12:34 | 0:12:38 | |

In the 19th century, a giraffe named Zarafa, Arabic for "charming one," | 0:12:40 | 0:12:46 | |

made a big impact on Europe socially and scientifically. | 0:12:46 | 0:12:50 | |

She was one of three captured in 1826 at the order of the Viceroy of Egypt, | 0:12:50 | 0:12:56 | |

who wanted to use them as gifts | 0:12:56 | 0:12:59 | |

to curry favour with France, Austria and England. | 0:12:59 | 0:13:03 | |

Zarafa, the strongest of the three, was given to the French, | 0:13:03 | 0:13:07 | |

seen here in a painting by Jacques Raymond Brascassat. | 0:13:07 | 0:13:11 | |

She travelled from Egypt to Marseilles by ship. | 0:13:11 | 0:13:16 | |

On reaching France, her keepers felt it was too risky to continue by boat, | 0:13:17 | 0:13:22 | |

so the decision was made to walk Zarafa from Marseille in the south | 0:13:22 | 0:13:28 | |

all the way to Paris, | 0:13:28 | 0:13:30 | |

an overland journey of more than 550 miles. | 0:13:30 | 0:13:34 | |

To some, this looked like a journey doomed to failure, | 0:13:34 | 0:13:38 | |

but careful planning and the unique biology of the giraffe | 0:13:38 | 0:13:42 | |

were in its favour. | 0:13:42 | 0:13:44 | |

Very wisely, a forward-thinking and eminent French scientist | 0:13:44 | 0:13:48 | |

called Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire was put in charge of the giraffe. | 0:13:48 | 0:13:52 | |

But there was something very significant about Zarafa | 0:13:52 | 0:13:56 | |

that would be key to the success of her long journey, | 0:13:56 | 0:13:59 | |

it was her age. | 0:13:59 | 0:14:01 | |

She was a youngster, just eight months old. | 0:14:01 | 0:14:05 | |

Baby giraffes are very robust | 0:14:05 | 0:14:08 | |

and can stand up and run within an hour of being born. | 0:14:08 | 0:14:12 | |

They have particularly long legs in relation to their bodies, | 0:14:12 | 0:14:16 | |

only half a metre shorter than those of an adult. | 0:14:16 | 0:14:20 | |

Such long legs help them keep up with their mothers, | 0:14:20 | 0:14:24 | |

so young Zarafa was well-equipped for walking. | 0:14:24 | 0:14:28 | |

Crucial too was the fuel for Zarafa's journey. | 0:14:33 | 0:14:36 | |

Young giraffe suckle for up to a year and Zarafa was bottle-fed. | 0:14:36 | 0:14:42 | |

Throughout the journey, she drank up to 25 litres of milk a day, | 0:14:42 | 0:14:47 | |

supplied by three milking cows. | 0:14:47 | 0:14:50 | |

She marched on at a steady pace with her trusty entourage. | 0:14:54 | 0:14:59 | |

After nearly 200 miles, Zarafa reached Lyon | 0:15:01 | 0:15:05 | |

and Saint-Hilaire broke the walk. | 0:15:05 | 0:15:08 | |

He hoped to put Zarafa onto a boat | 0:15:08 | 0:15:10 | |

to go down-river for the rest of the journey. | 0:15:10 | 0:15:12 | |

As they waited, 30,000 people flocked to see Zarafa. | 0:15:12 | 0:15:17 | |

To the public, she was a strange and exotic creature, | 0:15:17 | 0:15:21 | |

and they were intrigued why such a long neck should exist, | 0:15:21 | 0:15:24 | |

and curious about how an animal could support its weight. | 0:15:24 | 0:15:28 | |

In those early days, giraffe were seen as freaks, strange horned camels | 0:15:28 | 0:15:34 | |

whose humps had been flattened by the stretching of their necks. | 0:15:34 | 0:15:37 | |

But this was exactly what attracted Saint-Hilaire to Zarafa. | 0:15:37 | 0:15:42 | |

He was fascinated by genetic exaggerations | 0:15:42 | 0:15:45 | |

and how they came to be. | 0:15:45 | 0:15:47 | |

Clearly, the giraffe's long neck | 0:15:47 | 0:15:50 | |

enables them to feed on leaves beyond the reach of other browsers. | 0:15:50 | 0:15:54 | |

But how could they physically hold up such a long neck vertically? | 0:15:54 | 0:15:59 | |

DAVID LAUGHS | 0:16:01 | 0:16:03 | |

Studies of giraffe anatomy | 0:16:03 | 0:16:05 | |

have revealed just how the neck is supported. | 0:16:05 | 0:16:08 | |

A long thick ligament like a cable runs the whole length of the neck. | 0:16:08 | 0:16:14 | |

This counterbalances the weight of the head and the neck, | 0:16:14 | 0:16:18 | |

and in its relaxed position, it's tight. | 0:16:18 | 0:16:21 | |

So keeping the neck straight and the head up | 0:16:21 | 0:16:24 | |

involves very little muscular effort. | 0:16:24 | 0:16:27 | |

Bending the neck to reach down is more difficult, | 0:16:27 | 0:16:31 | |

because the tough ligament has to be stretched. | 0:16:31 | 0:16:34 | |

But was the ability to feed from tall trees | 0:16:35 | 0:16:39 | |

the only reason for having a long neck? | 0:16:39 | 0:16:42 | |

As the habits of giraffe in the wild became better known, | 0:16:42 | 0:16:46 | |

people discovered that rival males | 0:16:46 | 0:16:49 | |

fought one another by jousting with their necks. | 0:16:49 | 0:16:52 | |

Was that the reason that they had developed long necks? | 0:16:52 | 0:16:55 | |

But then someone pointed out that the females had long necks too, | 0:16:55 | 0:17:00 | |

so that suggestion was discarded. | 0:17:00 | 0:17:02 | |

In truth, there isn't a neat single answer, | 0:17:02 | 0:17:06 | |

but access to high food, better vigilance | 0:17:06 | 0:17:09 | |

and temperature regulation may all have shaped the giraffe's long neck. | 0:17:09 | 0:17:14 | |

As she walked on, Zarafa continued to attract inquisitive onlookers, | 0:17:16 | 0:17:21 | |

few had set eyes on such a creature, she appeared a natural impossibility. | 0:17:21 | 0:17:25 | |

How could a giraffe pump the blood up such a long neck to its brain? | 0:17:25 | 0:17:31 | |

And why didn't the blood rush back down into its feet? | 0:17:31 | 0:17:35 | |

The giraffe's neck may be very tall, | 0:17:38 | 0:17:41 | |

but, in fact, it contains exactly the same number of bones as our own, | 0:17:41 | 0:17:45 | |

that is to say seven. | 0:17:45 | 0:17:47 | |

But its blood pressure is twice as high as ours. | 0:17:47 | 0:17:51 | |

In fact, it's higher than any other known animal. | 0:17:51 | 0:17:55 | |

The pump that produces this pressure, the heart, | 0:17:55 | 0:17:59 | |

surprisingly is not particularly big but it is hugely powerful. | 0:17:59 | 0:18:03 | |

This is the left ventricle that has been cut through | 0:18:03 | 0:18:07 | |

and you can see how thick the muscle is, getting on for about 8cm. | 0:18:07 | 0:18:11 | |

This great pump produces blood, | 0:18:11 | 0:18:15 | |

squirts it up the artery to the head, | 0:18:15 | 0:18:17 | |

and then when it comes down through the jugular vein | 0:18:17 | 0:18:22 | |

there are pocket-shaped valves | 0:18:22 | 0:18:24 | |

which prevent the blood from flowing backwards into the head | 0:18:24 | 0:18:27 | |

if the animal lowers its head in order to have a drink. | 0:18:27 | 0:18:31 | |

Giraffes find it very awkward to drink from the ground. | 0:18:31 | 0:18:35 | |

And, in fact, they rarely do so, | 0:18:35 | 0:18:37 | |

they get most of their water from leaves and shoots. | 0:18:37 | 0:18:40 | |

The only way to get their mouth down to the water | 0:18:40 | 0:18:44 | |

is to splay their forelegs or bend them at the wrist joint. | 0:18:44 | 0:18:48 | |

The giraffe, in fact, has a relatively short neck compared to its legs. | 0:18:51 | 0:18:56 | |

Antelope and zebra can reach down to the ground | 0:18:57 | 0:19:01 | |

without bending their legs. | 0:19:01 | 0:19:03 | |

Only the giraffe and its rainforest relative the okapi | 0:19:03 | 0:19:06 | |

have necks that are so short relative to their legs | 0:19:06 | 0:19:09 | |

that they must splay or bend them. | 0:19:09 | 0:19:12 | |

So perhaps the most remarkable feature of the giraffe | 0:19:13 | 0:19:16 | |

is the length of its legs. | 0:19:16 | 0:19:18 | |

They certainly were key to Zarafa's success. | 0:19:18 | 0:19:21 | |

At Lyon, there was a plan to rest her legs from walking | 0:19:21 | 0:19:25 | |

and to finish the journey to Paris by boat, | 0:19:25 | 0:19:28 | |

but all didn't go according to plan. | 0:19:28 | 0:19:30 | |

The boat didn't appear in Lyon, | 0:19:31 | 0:19:34 | |

so she walked on and finally got to Paris. | 0:19:34 | 0:19:37 | |

It's took her a total of 41 days | 0:19:37 | 0:19:40 | |

to complete the journey of 550 miles to Paris. | 0:19:40 | 0:19:44 | |

Saint-Hilaire, her trusty companion, was exhausted, | 0:19:44 | 0:19:48 | |

but the giraffe was very fit. | 0:19:48 | 0:19:50 | |

He wrote, "She gained weight and much more strength from the exercise. | 0:19:50 | 0:19:55 | |

"Her muscles were more defined, her coat smoother and glossier | 0:19:55 | 0:19:59 | |

"upon her arrival than they were in Marseille." | 0:19:59 | 0:20:03 | |

Zarafa was presented to King Charles X | 0:20:03 | 0:20:07 | |

and temporarily installed in a greenhouse | 0:20:07 | 0:20:10 | |

in the grounds of the Jardin des Plantes. | 0:20:10 | 0:20:13 | |

She was a true animal ambassador | 0:20:13 | 0:20:15 | |

and 60,000 people saw her in the first three weeks in Paris. | 0:20:15 | 0:20:20 | |

In the early 19th century, giraffes were a novelty | 0:20:20 | 0:20:24 | |

and their biology and lives in the wild was still a mystery. | 0:20:24 | 0:20:28 | |

Zarafa's success was due to a unique interplay | 0:20:28 | 0:20:32 | |

of the giraffe's unusual characteristics and good timing. | 0:20:32 | 0:20:36 | |

Her youth, long legs and a diet with milk | 0:20:36 | 0:20:40 | |

powered her journey right across France. | 0:20:40 | 0:20:44 | |

A body that was first considered bizarre | 0:20:46 | 0:20:49 | |

was revealed to be perfectly evolved. | 0:20:49 | 0:20:52 | |

Our story began with three giraffe that were given to Europe. | 0:20:54 | 0:20:59 | |

Zarafa was the most robust of them and she lived a further 18 years. | 0:20:59 | 0:21:04 | |

The Austrian lasted just a year. | 0:21:04 | 0:21:08 | |

And the one sent to King George IV of England died after two. | 0:21:08 | 0:21:13 | |

Saint-Hilaire learnt much from Zarafa | 0:21:13 | 0:21:16 | |

and he became a key figure | 0:21:16 | 0:21:17 | |

in the blossoming zoological research in France. | 0:21:17 | 0:21:21 | |

The giraffe brought to England | 0:21:21 | 0:21:23 | |

triggered a surge of interest in animal research | 0:21:23 | 0:21:25 | |

that shifted the centre of the zoological gravity | 0:21:25 | 0:21:28 | |

from France to England. | 0:21:28 | 0:21:30 | |

So we can thank Zarafa for her early role | 0:21:30 | 0:21:34 | |

in unravelling the biological mysteries | 0:21:34 | 0:21:36 | |

of the giraffe's extraordinary body and stretched neck. | 0:21:36 | 0:21:40 | |

When the first Europeans arrived in Australia, | 0:21:50 | 0:21:53 | |

they were shocked by the animals they found there. | 0:21:53 | 0:21:56 | |

Nothing in Europe could compare with the bizarre upright grazers | 0:21:56 | 0:22:01 | |

hopping across the grassland landscape | 0:22:01 | 0:22:04 | |

carrying their young in pouches. | 0:22:04 | 0:22:06 | |

Kangaroos were obvious oddities, | 0:22:06 | 0:22:08 | |

but another even stranger creature | 0:22:08 | 0:22:11 | |

also caught the attention of early settlers. | 0:22:11 | 0:22:13 | |

It lived along river banks and swam in the water. | 0:22:13 | 0:22:18 | |

Those first Europeans who saw it called it a "water mole," | 0:22:18 | 0:22:22 | |

but that name didn't last long. | 0:22:22 | 0:22:25 | |

Inside this box is one of the first specimens of platypus | 0:22:26 | 0:22:31 | |

ever to be seen outside Australia. | 0:22:31 | 0:22:33 | |

It was sent to England in 1798 by Captain John Hunter, | 0:22:40 | 0:22:44 | |

the Governor of New South Wales. | 0:22:44 | 0:22:47 | |

This one small animal would take the scientific world by storm | 0:22:47 | 0:22:51 | |

and transform the careers and reputations | 0:22:51 | 0:22:54 | |

of some of the leading thinkers of the time. | 0:22:54 | 0:22:56 | |

The platypus seemed to be a concoction of different animals, | 0:22:58 | 0:23:02 | |

part bird with its bill and part mammal with its furry body. | 0:23:02 | 0:23:07 | |

When Charles Darwin first encountered one in the wild, it baffled even him. | 0:23:07 | 0:23:12 | |

"Surely," he wrote, "two distinct creators must have been at work." | 0:23:12 | 0:23:16 | |

The task of describing the first platypus specimen | 0:23:20 | 0:23:23 | |

fell to naturalist George Shaw, | 0:23:23 | 0:23:25 | |

who worked in the Department of Natural History in the British Museum. | 0:23:25 | 0:23:30 | |

And he viewed this remarkable specimen | 0:23:30 | 0:23:32 | |

with a fair degree of caution. | 0:23:32 | 0:23:35 | |

This is a first edition of a journal called A Naturalist's Miscellany, | 0:23:36 | 0:23:40 | |

which was published a few years after his examination, | 0:23:40 | 0:23:44 | |

and it contains not only an article by him | 0:23:44 | 0:23:46 | |

but a nice picture of the animal concerned. | 0:23:46 | 0:23:50 | |

And at the end he says, "On a subject so extraordinary as the present, | 0:23:50 | 0:23:55 | |

"a degree of scepticism is not only pardonable but laudable. | 0:23:55 | 0:23:59 | |

"And I ought perhaps to acknowledge | 0:23:59 | 0:24:01 | |

"that I almost doubt the testimony of my own eyes | 0:24:01 | 0:24:05 | |

"with respect to the structure of this animal's beak." | 0:24:05 | 0:24:08 | |

It's said that Shaw was so determined to make sure | 0:24:08 | 0:24:11 | |

that he was not a victim of some elaborate hoax | 0:24:11 | 0:24:14 | |

that he actually cut behind the bill | 0:24:14 | 0:24:16 | |

to make sure it hand't been sewn on by some mischievous forger. | 0:24:16 | 0:24:20 | |

In the late 18th century, the world was opening up, | 0:24:22 | 0:24:25 | |

travellers were returning from overseas with all kinds of wonders. | 0:24:25 | 0:24:29 | |

Among them were specimens of creatures that people had come to think of as being myths, | 0:24:29 | 0:24:34 | |

such as mermen and mermaids. | 0:24:34 | 0:24:37 | |

These were, of course, hoaxes | 0:24:37 | 0:24:39 | |

put together with parts from different animals, | 0:24:39 | 0:24:41 | |

so it's understandable that Shaw had doubts | 0:24:41 | 0:24:45 | |

about the authenticity of his new furry specimen. | 0:24:45 | 0:24:48 | |

Despite his misgivings, he decided to give it a scientific name, | 0:24:50 | 0:24:54 | |

platypus, which means "flat footed." | 0:24:54 | 0:24:57 | |

He didn't know however that a beetle had already been given this name | 0:24:57 | 0:25:01 | |

and some years later, another taxonomist very properly gave it a new one, | 0:25:01 | 0:25:06 | |

Ornithorhynchus, which means "bird snout." | 0:25:06 | 0:25:10 | |

But platypus is still the name that most people use. | 0:25:10 | 0:25:15 | |

But what type of creature was it? | 0:25:15 | 0:25:17 | |

George Shaw believed it to be a mammal because of its furry body. | 0:25:17 | 0:25:22 | |

All mammals feed on milk during the first part of their lives, | 0:25:24 | 0:25:28 | |

milk that is produced by their mother's mammary glands. | 0:25:28 | 0:25:32 | |

But could an animal with a large flat bill really suckle? | 0:25:32 | 0:25:36 | |

Some scientists thought that was impossible, | 0:25:36 | 0:25:39 | |

and anyway they couldn't believe the platypus and the monkey | 0:25:39 | 0:25:42 | |

could belong to the same group of animals. | 0:25:42 | 0:25:45 | |

But that view was to change. | 0:25:45 | 0:25:47 | |

Some 30 years after George Shaw described the platypus, | 0:25:48 | 0:25:52 | |

a German naturalist, Johann Meckel, | 0:25:52 | 0:25:55 | |

produced this wonderful collection of anatomical studies. | 0:25:55 | 0:25:59 | |

Meckel's meticulous and detailed work | 0:25:59 | 0:26:01 | |

would help identify the true nature of this animal. | 0:26:01 | 0:26:05 | |

Here... | 0:26:05 | 0:26:07 | |

..we can see his drawing of a male platypus showing clearly the claw. | 0:26:08 | 0:26:15 | |

Meckel also reported the existence of simple glands | 0:26:15 | 0:26:18 | |

beneath the thick fur of the female platypus, | 0:26:18 | 0:26:21 | |

glands that he suggested secreted milk. | 0:26:21 | 0:26:24 | |

There could be little doubt that these glands produced something, | 0:26:24 | 0:26:28 | |

but even then several scientists doubted Meckel's claims | 0:26:28 | 0:26:32 | |

and suggested rather desperately | 0:26:32 | 0:26:34 | |

that the glands secreted not milk but a lubricant. | 0:26:34 | 0:26:37 | |

Today, we know that Meckel was right. | 0:26:37 | 0:26:40 | |

And I was once able to use an optical probe | 0:26:40 | 0:26:43 | |

to peer into a platypus' burrow | 0:26:43 | 0:26:45 | |

and see a female platypus nurturing her single baby. | 0:26:45 | 0:26:49 | |

Yes! And there it is, it's milk. | 0:26:50 | 0:26:53 | |

Milk is the perfect food, | 0:26:54 | 0:26:56 | |

it provides the growing youngster with everything it wants. | 0:26:56 | 0:27:01 | |

And only mammals produce milk. | 0:27:01 | 0:27:04 | |

In most mammals, of course, it comes from a nipple, | 0:27:04 | 0:27:08 | |

but in this very primitive mammal it simply oozes through the skin. | 0:27:08 | 0:27:13 | |

But 19th-century biologists had no such tricks to help them, | 0:27:14 | 0:27:19 | |

they had to unravel the strange biology of Australian mammals | 0:27:19 | 0:27:23 | |

from just a few shrivelled remains of long-dead specimens. | 0:27:23 | 0:27:27 | |

40 years after their discovery of the platypus, | 0:27:28 | 0:27:31 | |

a brilliant young anatomist, who was to become a giant of 19th-century science, joined the debate. | 0:27:31 | 0:27:37 | |

This is a statue of Richard Owen. | 0:27:37 | 0:27:40 | |

Owen was a formidable man, | 0:27:40 | 0:27:43 | |

the founding Director of the Natural History Museum in Britain, | 0:27:43 | 0:27:46 | |

he was once described as having so much brain as to require two hats. | 0:27:46 | 0:27:51 | |

The platypus would become a central character in Owen's career. | 0:27:51 | 0:27:56 | |

His work on this small creature | 0:27:56 | 0:27:58 | |

would help him secure election to the prestigious Royal Society, | 0:27:58 | 0:28:01 | |

an exclusive group of scientists and thinkers. | 0:28:01 | 0:28:04 | |

Owen had an advantage over his European colleagues. | 0:28:06 | 0:28:10 | |

Australia was a British colony | 0:28:10 | 0:28:13 | |

and Owen used his contacts to supply him with specimens. | 0:28:13 | 0:28:17 | |

Eventually, two baby platypuses arrived | 0:28:19 | 0:28:23 | |

and it was obvious to him that they would have no difficulty in suckling. | 0:28:23 | 0:28:27 | |

They had not yet developed the bill that would have made it awkward. | 0:28:28 | 0:28:32 | |

So he accepted that platypus babies like other mammal babies | 0:28:32 | 0:28:37 | |

were indeed raised on milk. | 0:28:37 | 0:28:39 | |

But the biggest mystery of the platypus was still unsolved. | 0:28:41 | 0:28:45 | |

Did this animal lay eggs just like reptiles or birds, | 0:28:46 | 0:28:51 | |

or did it give birth to live young? | 0:28:51 | 0:28:54 | |

Owen was at the heart of that debate. | 0:28:54 | 0:28:57 | |

These jars contain the bodies of several platypus | 0:28:58 | 0:29:01 | |

that were shot and sent back here to the museum | 0:29:01 | 0:29:03 | |

for Richard Owen to examine. | 0:29:03 | 0:29:06 | |

His determination to prove whether or not they laid eggs | 0:29:06 | 0:29:09 | |

was going to cause the death of quite a number of platypus. | 0:29:09 | 0:29:13 | |

The Australian aborigines were absolutely clear, | 0:29:13 | 0:29:16 | |

they did lay eggs, but that was not good enough for Owen, | 0:29:16 | 0:29:20 | |

he knew better then any Australian aboriginal. | 0:29:20 | 0:29:23 | |

He did concede that it might be | 0:29:23 | 0:29:26 | |

that the eggs were retained inside the body and hatched there | 0:29:26 | 0:29:29 | |

so that the young were born live, but that's as far as he would go. | 0:29:29 | 0:29:33 | |

Eggs were also sent back. | 0:29:33 | 0:29:35 | |

Some of them were fake and some of them belonged to snakes. | 0:29:35 | 0:29:39 | |

It was going to be some decades | 0:29:39 | 0:29:41 | |

before the puzzle of the platypus was finally solved. | 0:29:41 | 0:29:45 | |

The platypus now became embroiled | 0:29:47 | 0:29:49 | |

in the greatest scientific debate of the Victorian era. | 0:29:49 | 0:29:53 | |

Did species evolve or were they created? | 0:29:53 | 0:29:57 | |

Darwin's Theory of Evolution | 0:29:57 | 0:29:59 | |

suggested that species could change over time, | 0:29:59 | 0:30:02 | |

so an intermediate form that laid eggs but had fur like a mammal | 0:30:02 | 0:30:06 | |

was to be expected. | 0:30:06 | 0:30:08 | |

But that was too much of a stretch even for Owen's great brain. | 0:30:08 | 0:30:12 | |

In 1884, more than 80 years after this first platypus specimen | 0:30:13 | 0:30:18 | |

had been examined by George Shaw, | 0:30:18 | 0:30:20 | |

William Hay Caldwell arrived in Australia funded by a Royal Society scholarship. | 0:30:20 | 0:30:26 | |

One of his main aims was to solve the platypus egg question once and for all. | 0:30:26 | 0:30:31 | |

After several months in Queensland, | 0:30:31 | 0:30:33 | |

and with the help of the local aborigines, | 0:30:33 | 0:30:35 | |

he finally got the answer. | 0:30:35 | 0:30:37 | |

He shot a female platypus | 0:30:37 | 0:30:39 | |

soon after she had laid an egg in her nest burrow | 0:30:39 | 0:30:43 | |

with a second egg about to emerge from her vent. | 0:30:43 | 0:30:46 | |

And they looked like this. | 0:30:46 | 0:30:49 | |

It was at last visible evidence that this animal did indeed lay eggs. | 0:30:50 | 0:30:55 | |

He sent a telegram to a scientific gathering in Montreal, | 0:30:55 | 0:30:59 | |

it was brief and to the point, | 0:30:59 | 0:31:01 | |

"Monotremes oviparous, ovum meroblastic." | 0:31:01 | 0:31:05 | |

These four words to the scientifically initiated | 0:31:05 | 0:31:09 | |

meant that the platypus laid eggs | 0:31:09 | 0:31:12 | |

and that the eggs consisted of an undivided large yolk | 0:31:12 | 0:31:15 | |

just like a bird's egg. | 0:31:15 | 0:31:18 | |

The mystery was at last solved. | 0:31:18 | 0:31:21 | |

Richard Owen, who had refused to believe a mammal could lay an egg, | 0:31:23 | 0:31:27 | |

was by now 80 years old and he was no longer held in the same esteem | 0:31:27 | 0:31:32 | |

as in the early part of his career. | 0:31:32 | 0:31:35 | |

The platypus had helped establish his reputation, | 0:31:35 | 0:31:38 | |

but now the riddle of this creature's reproduction had proved him wrong. | 0:31:38 | 0:31:42 | |

It's extraordinary to think that this small animal | 0:31:44 | 0:31:47 | |

fooled and confounded many of the great scientific minds of 19th-century Europe. | 0:31:47 | 0:31:52 | |

Not a hoax, but a true curiosity and one like no other. | 0:31:52 | 0:31:57 | |

The egg-laying platypus was hardly believable to Victorian researchers, | 0:32:00 | 0:32:05 | |

but evolution has thrown up many unusual mating strategies | 0:32:05 | 0:32:09 | |

and in the early part of the 20th century, | 0:32:09 | 0:32:12 | |

the anatomy of a particular amphibian started an argument | 0:32:12 | 0:32:16 | |

that, like the platypus, led to accusations of forgery. | 0:32:16 | 0:32:20 | |

This is the curious tale of the midwife toad. | 0:32:20 | 0:32:24 | |

Midwife toads are not native to Britain, | 0:32:27 | 0:32:29 | |

they were introduce about a century ago | 0:32:29 | 0:32:32 | |

and since then have been slowly spreading over England. | 0:32:32 | 0:32:35 | |

Their natural home is Europe, from Germany to Spain. | 0:32:35 | 0:32:39 | |

And in the 1920s, their mating habits caused a media sensation. | 0:32:39 | 0:32:45 | |

Investigations into the way the body of the male toad | 0:32:46 | 0:32:50 | |

changed according to its environment led some to believe | 0:32:50 | 0:32:54 | |

it might be possible to breed a race of superhumans. | 0:32:54 | 0:32:58 | |

To understand why, we must first know | 0:32:58 | 0:33:01 | |

what makes the midwife toad so different from any other frog or toad. | 0:33:01 | 0:33:07 | |

Amphibians were among the first backboned animals to take to the land. | 0:33:07 | 0:33:11 | |

Since then, they've colonised most habitats | 0:33:11 | 0:33:15 | |

from rainforests to deserts and mountains. | 0:33:15 | 0:33:19 | |

Despite spending much of their lives on land, | 0:33:19 | 0:33:22 | |

most frogs and toads need water to reproduce, | 0:33:22 | 0:33:25 | |

whether it be in a small vase plant or a large lake. | 0:33:25 | 0:33:28 | |

But mating in water is a slippery business. | 0:33:28 | 0:33:32 | |

Male toads, however, have a special adaptation, | 0:33:32 | 0:33:35 | |

black warty swellings on their wrists called nuptial pads, | 0:33:35 | 0:33:39 | |

which enable them to grip their partners securely during sex. | 0:33:39 | 0:33:43 | |

Once the female produces her eggs, | 0:33:43 | 0:33:46 | |

the male releases his sperm and then let's go, his job is done. | 0:33:46 | 0:33:50 | |

But midwife toads are different, | 0:33:50 | 0:33:53 | |

the male does not have nuptial pads on his wrists. | 0:33:53 | 0:33:57 | |

And that's because he doesn't mate in water, he mates on land. | 0:33:58 | 0:34:03 | |

The female produces her eggs and then he takes them around his legs | 0:34:03 | 0:34:08 | |

with an action that's been compared to a man trying to put on his trousers without using his hands. | 0:34:08 | 0:34:15 | |

So it is the male toad that is the actual midwife, not the female. | 0:34:17 | 0:34:22 | |

Midwife toads tend to live in places where open water is scarce. | 0:34:22 | 0:34:27 | |

Once the male has successfully wrapped a string of eggs around his legs, | 0:34:29 | 0:34:33 | |

he usually hides under a rock where it's suitably damp. | 0:34:33 | 0:34:37 | |

He may have as many as 150 eggs | 0:34:42 | 0:34:46 | |

and he hides away for up to two months while they develop. | 0:34:46 | 0:34:49 | |

Then, just before the eggs hatch, | 0:34:49 | 0:34:52 | |

he sets off to find water for his emerging tadpoles. | 0:34:52 | 0:34:56 | |

Now, the tadpoles of most frogs and toads | 0:34:58 | 0:35:02 | |

turn into the adult form within a matter of weeks, | 0:35:02 | 0:35:06 | |

but not so the midwife toad - it takes much, much longer. | 0:35:06 | 0:35:10 | |

In fact, sometimes they may even overwinter in the form of a tadpole, | 0:35:10 | 0:35:16 | |

which is why perhaps midwife toad tadpoles are such whoppers. | 0:35:16 | 0:35:21 | |

Frogs and toads are widely used in biological studies | 0:35:22 | 0:35:26 | |

because they're easy to keep | 0:35:26 | 0:35:28 | |

and the different stages of their life cycles are easy to observe. | 0:35:28 | 0:35:32 | |

So it's no surprise that the unusual behaviour of the midwife toad | 0:35:32 | 0:35:36 | |

should attract the attention of many biologists. | 0:35:36 | 0:35:39 | |

One was an Austrian scientist called Paul Kammerer, | 0:35:40 | 0:35:43 | |

who worked in Vienna in the early part of the 20th century. | 0:35:43 | 0:35:47 | |

And his discoveries quickly brought him great fame. | 0:35:47 | 0:35:51 | |

But the toad would become a curse | 0:35:52 | 0:35:55 | |

that would haunt him until the end of his life. | 0:35:55 | 0:35:58 | |

Kammerer was greatly influenced | 0:36:00 | 0:36:02 | |

by the great French zoologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, | 0:36:02 | 0:36:06 | |

who, in 1799, published his theory | 0:36:06 | 0:36:09 | |

that characteristics acquired by an animal during its life | 0:36:09 | 0:36:13 | |

could be inherited by its offspring. | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

That a giraffe, for example, | 0:36:16 | 0:36:17 | |

reaching upwards to nibble the topmost shoots of trees | 0:36:17 | 0:36:21 | |

would, over time, lengthen its neck muscles | 0:36:21 | 0:36:24 | |

and that this increase would then be inherited by its offspring. | 0:36:24 | 0:36:28 | |

And so on for generation after generation. | 0:36:28 | 0:36:31 | |

Lamarck's theory was largely rejected after Charles Darwin proposed | 0:36:31 | 0:36:37 | |

a different mechanism for evolution | 0:36:37 | 0:36:39 | |

based on changes to an animal's genetic make-up. | 0:36:39 | 0:36:43 | |

Kammerer was keen to prove that Lamarck was right after all. | 0:36:43 | 0:36:48 | |

But giraffes are not the ideal experimental animal, | 0:36:48 | 0:36:51 | |

so he needed one he could keep in a lab and that would reproduce quickly. | 0:36:51 | 0:36:56 | |

And his attention fell on the midwife toad. | 0:36:56 | 0:36:59 | |

Kammerer became fascinated | 0:36:59 | 0:37:01 | |

with the unusual nature of the midwife toad's reproduction. | 0:37:01 | 0:37:05 | |

Why did males like this one | 0:37:05 | 0:37:08 | |

carry eggs around his legs and could this be changed? | 0:37:08 | 0:37:12 | |

He wondered if their biology might be related to their natural environment, which is largely arid. | 0:37:12 | 0:37:18 | |

Kammerer decided to see what would happen | 0:37:18 | 0:37:22 | |

if he kept the toads in a warm, humid tank | 0:37:22 | 0:37:24 | |

with access to pools of cool water. | 0:37:24 | 0:37:27 | |

His work with the toads would last many years | 0:37:27 | 0:37:30 | |

and involve several generations, but eventually he noticed changes. | 0:37:30 | 0:37:34 | |

Some male toads abandoned carrying the eggs | 0:37:34 | 0:37:38 | |

and instead the females laid them directly in water. | 0:37:38 | 0:37:42 | |

Over several generations, Kammerer had managed to change the midwife toad | 0:37:44 | 0:37:50 | |

from being a land-breeding animal to one that bred in water. | 0:37:50 | 0:37:55 | |

But the most extraordinary discovery came as he continued breeding these toads. | 0:37:55 | 0:38:00 | |

He noticed that the wrists of some of the males | 0:38:00 | 0:38:04 | |

developed warty-looking structures | 0:38:04 | 0:38:06 | |

just like the nuptial pads of other frogs and toads | 0:38:06 | 0:38:09 | |

which are normally used by males | 0:38:09 | 0:38:12 | |

to grip females when fertilising her eggs. | 0:38:12 | 0:38:15 | |

His work suggested that somehow, | 0:38:15 | 0:38:17 | |

by altering the environment in which they lived, | 0:38:17 | 0:38:20 | |

a toad's body could be changed | 0:38:20 | 0:38:22 | |

and that change was then passed on to future generations. | 0:38:22 | 0:38:27 | |

Kammerer's work was taking place at the end of the First World War | 0:38:27 | 0:38:32 | |

and political movements on the left and the right | 0:38:32 | 0:38:34 | |

were then keen to exploit scientific discoveries. | 0:38:34 | 0:38:38 | |

Despite his subject being a small toad, | 0:38:38 | 0:38:41 | |

some saw an opportunity to extend his findings beyond the laboratory. | 0:38:41 | 0:38:46 | |

He was hailed as a second Darwin in the New York Times. | 0:38:47 | 0:38:51 | |

Some newspapers got carried away | 0:38:51 | 0:38:53 | |

and suggested that Kammerer's discoveries could apply to humans. | 0:38:53 | 0:38:56 | |

His work could help, in other words, to breed a race of superhumans. | 0:38:56 | 0:39:02 | |

Whether he liked it or not, Kammerer was now in the spotlight. | 0:39:02 | 0:39:06 | |

He set off on a lecture tour across Europe and America. | 0:39:06 | 0:39:11 | |

In Cambridge, the Professor of Zoology hailed his achievements | 0:39:11 | 0:39:14 | |

and put one of Kammerer's toads on display. | 0:39:14 | 0:39:17 | |

But not everyone was convinced. | 0:39:17 | 0:39:20 | |

An American zoologist by the name of GK Noble wrote a damning article | 0:39:20 | 0:39:24 | |

in the prestigious scientific journal Nature. | 0:39:24 | 0:39:28 | |

Noble examined one of Kammerer's toad | 0:39:28 | 0:39:31 | |

and declared that its black nuptial pads were fakes, | 0:39:31 | 0:39:34 | |

produced by injecting a black dye. | 0:39:34 | 0:39:36 | |

Kammerer denied this. Someone, he said, had interfered with his specimens | 0:39:38 | 0:39:42 | |

and was trying to ruin him. | 0:39:42 | 0:39:44 | |

But the damage to his name was done. | 0:39:44 | 0:39:48 | |

Six weeks after the Nature article accusing him of forgery, | 0:39:48 | 0:39:51 | |

Kammerer wrote a letter to another leading scientific journal. | 0:39:51 | 0:39:55 | |

This is an extract of what it said. | 0:39:55 | 0:39:58 | |

"On the basis of this state of affairs, | 0:40:00 | 0:40:02 | |

"I dare not, although I myself have no part in these falsifications of my prior specimens, | 0:40:02 | 0:40:09 | |

"any longer consider myself a proper man to accept your call. | 0:40:09 | 0:40:14 | |

"I see that I'm also not in a position to endure this wrecking of my life's work, | 0:40:14 | 0:40:20 | |

"and I hope I shall gather together enough courage and strength | 0:40:20 | 0:40:23 | |

"to put an end of my wrecked life tomorrow." | 0:40:23 | 0:40:26 | |

Soon after writing that letter, | 0:40:28 | 0:40:30 | |

he walked into the hills around his home and shot himself. | 0:40:30 | 0:40:35 | |

Whether or not Kammerer's suicide | 0:40:35 | 0:40:37 | |

was purely down to the fallout from his midwife-toad experiments, we can't be sure - | 0:40:37 | 0:40:42 | |

there were many other problems in his personal life - | 0:40:42 | 0:40:45 | |

but there can be little doubt that the scandal surrounding his work | 0:40:45 | 0:40:49 | |

would have weighed heavily on his mind. | 0:40:49 | 0:40:52 | |

Since Kammerer's death, a specimen of male midwife toad | 0:40:52 | 0:40:57 | |

WITH nuptial pads has been found in the wild. | 0:40:57 | 0:41:00 | |

Some scientists now believe | 0:41:00 | 0:41:02 | |

that environmental influences can change the way some genes behave | 0:41:02 | 0:41:07 | |

and that these changes can indeed be passed on to the next generation. | 0:41:07 | 0:41:12 | |

Perhaps midwife toads possess the gene to grow these structures, | 0:41:12 | 0:41:16 | |

but it's only switched on in certain situations. | 0:41:16 | 0:41:20 | |

Does this prove Kammerer was right? | 0:41:20 | 0:41:23 | |

No-one has been able to repeat Kammerer's experiments with midwife toads, | 0:41:23 | 0:41:27 | |

so we don't know for sure if he falsified his findings, | 0:41:27 | 0:41:30 | |

or whether he had stumbled upon a quirk of inheritance ahead of its time | 0:41:30 | 0:41:35 | |

and beyond the understanding of scientists of his era. | 0:41:35 | 0:41:38 | |

What is certain is that the nature of how species inherit their characteristics | 0:41:38 | 0:41:44 | |

is more complex than he or others at the time originally thought. | 0:41:44 | 0:41:49 | |

The curious lives of the midwife toad and the duck-billed platypus | 0:41:51 | 0:41:55 | |

perplexed and wrong-footed science for some considerable time. | 0:41:55 | 0:41:59 | |

But in the end, both these creatures | 0:41:59 | 0:42:02 | |

helped us to better understand the way animals evolve. | 0:42:02 | 0:42:07 |