Episode 2 David Attenborough's Natural Curiosities

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Episode 2. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

How did two small animals from opposite ends of the world | 0:00:02 | 0:00:05 | |

upset the reputations of leading scientists | 0:00:05 | 0:00:07 | |

and change our understanding of evolution? | 0:00:07 | 0:00:10 | |

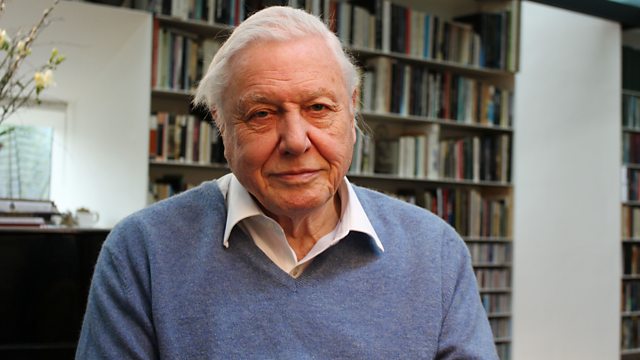

I've been lucky enough, one way or another, | 0:00:12 | 0:00:14 | |

to meet some of our planet's most enchanting creatures. | 0:00:14 | 0:00:18 | |

But some I find particularly intriguing. | 0:00:18 | 0:00:21 | |

We've known about some of these creatures for centuries. | 0:00:23 | 0:00:27 | |

Others we have discovered more recently. | 0:00:27 | 0:00:30 | |

In this series, I share their stories | 0:00:31 | 0:00:34 | |

and reveal why they really are natural curiosities. | 0:00:34 | 0:00:38 | |

In this programme, we explore the stories of two animals | 0:00:45 | 0:00:48 | |

that sent shock waves through the scientific world and beyond. | 0:00:48 | 0:00:54 | |

One is a toad that became the centre of a scientific storm | 0:00:54 | 0:00:58 | |

and caused accusations of fakery in the early part of the 20th century. | 0:00:58 | 0:01:02 | |

The other is an Australian animal | 0:01:05 | 0:01:06 | |

that baffled the greatest thinkers of Victorian Europe | 0:01:06 | 0:01:10 | |

and caused many to question whether it was even real. | 0:01:10 | 0:01:13 | |

When the first Europeans arrived in Australia, | 0:01:26 | 0:01:29 | |

they were shocked by the animals they found there. | 0:01:29 | 0:01:32 | |

Nothing in Europe could compare with the bizarre upright grazers | 0:01:32 | 0:01:37 | |

hopping across the grassland landscape, | 0:01:37 | 0:01:39 | |

carrying their young in pouches. | 0:01:39 | 0:01:42 | |

Kangaroos were obvious oddities, but another even stranger creature | 0:01:42 | 0:01:47 | |

also caught the attention of early settlers. | 0:01:47 | 0:01:50 | |

It lived along river banks and swam in the water. | 0:01:50 | 0:01:54 | |

Those first Europeans who saw it called it a water mole, | 0:01:54 | 0:01:58 | |

but that name didn't last long. | 0:01:58 | 0:02:00 | |

Inside this box is one of the first specimens of platypus | 0:02:02 | 0:02:06 | |

ever to be seen outside Australia. | 0:02:06 | 0:02:09 | |

It was sent to England in 1798 by Captain John Hunter, | 0:02:16 | 0:02:20 | |

the governor of New South Wales. | 0:02:20 | 0:02:23 | |

This one small animal would take the scientific world by storm | 0:02:23 | 0:02:27 | |

and transform the careers and reputations | 0:02:27 | 0:02:29 | |

of some of the leading thinkers of the time. | 0:02:29 | 0:02:33 | |

The platypus seemed to be a concoction of different animals. | 0:02:34 | 0:02:38 | |

Part-bird, with its bill, and part mammal, with its furry body. | 0:02:38 | 0:02:43 | |

When Charles Darwin first encountered one in the wild, | 0:02:43 | 0:02:46 | |

it baffled even him. | 0:02:46 | 0:02:48 | |

"Surely," he wrote, "two distinct creators must have been at work." | 0:02:48 | 0:02:52 | |

The task of describing the first platypus specimen | 0:02:55 | 0:02:59 | |

fell to naturalist George Shaw, | 0:02:59 | 0:03:01 | |

who worked in the department of natural history | 0:03:01 | 0:03:04 | |

in the British Museum. | 0:03:04 | 0:03:05 | |

He viewed this remarkable specimen with a fair degree of caution. | 0:03:05 | 0:03:10 | |

This is a first edition of a journal called A Naturalist's Miscellany, | 0:03:11 | 0:03:15 | |

which was published a few years after his examination. | 0:03:15 | 0:03:19 | |

It contains not only an article by him, | 0:03:19 | 0:03:22 | |

but a nice picture of the animal concerned. | 0:03:22 | 0:03:25 | |

At the end, he says, "On a subject so extraordinary as the present, | 0:03:25 | 0:03:31 | |

"a degree of scepticism is not only pardonable but laudable. | 0:03:31 | 0:03:35 | |

"I ought, perhaps, to acknowledge that I almost doubt the testimony | 0:03:35 | 0:03:39 | |

"of my own eyes with respect to the structure of this animal's beak." | 0:03:39 | 0:03:45 | |

It's said that Shaw was so determined to make sure | 0:03:45 | 0:03:47 | |

that he was not a victim of some elaborate hoax | 0:03:47 | 0:03:50 | |

that he actually cut behind the bill | 0:03:50 | 0:03:52 | |

to make sure that it hadn't been sewn on | 0:03:52 | 0:03:54 | |

by some mischievous forger. | 0:03:54 | 0:03:56 | |

In the late 18th century, the world was opening up. | 0:03:58 | 0:04:01 | |

Travellers were returning from overseas with all kinds of wonders. | 0:04:01 | 0:04:05 | |

Among them were specimens of creatures | 0:04:05 | 0:04:07 | |

that people had come to think of as being myths, | 0:04:07 | 0:04:10 | |

such as mermen and mermaids. | 0:04:10 | 0:04:12 | |

These were, of course, hoaxes, | 0:04:12 | 0:04:14 | |

put together with parts from different animals. | 0:04:14 | 0:04:17 | |

So it's understandable that Shaw had doubts about the authenticity | 0:04:17 | 0:04:21 | |

of his new furry specimen. | 0:04:21 | 0:04:23 | |

Despite his misgivings, he decided to give it a scientific name - | 0:04:25 | 0:04:29 | |

platypus, which means flat-footed. | 0:04:29 | 0:04:33 | |

He didn't know, however, | 0:04:33 | 0:04:34 | |

that a beetle had already been given this name. | 0:04:34 | 0:04:37 | |

Some years later, another taxonomist very properly gave it a new one - | 0:04:37 | 0:04:42 | |

Ornithorhynchus, which means bird snout. | 0:04:42 | 0:04:46 | |

But platypus is still the name that most people use. | 0:04:46 | 0:04:49 | |

But what type of creature was it? | 0:04:51 | 0:04:53 | |

George Shaw believed it to be a mammal because of its furry body. | 0:04:53 | 0:04:57 | |

All mammals feed on milk during the first part of their lives. | 0:04:59 | 0:05:04 | |

Milk that is produced by their mother's mammary glands. | 0:05:04 | 0:05:08 | |

But could an animal with a large, flat bill really suckle? | 0:05:08 | 0:05:12 | |

Some scientists thought that was impossible. | 0:05:12 | 0:05:15 | |

And, anyway, they couldn't believe the platypus and the monkey | 0:05:15 | 0:05:18 | |

could belong to the same group of animals. | 0:05:18 | 0:05:21 | |

But that view was to change. | 0:05:21 | 0:05:23 | |

Some 30 years after George Shaw described the platypus, | 0:05:24 | 0:05:28 | |

a German naturalist, Johann Meckel, | 0:05:28 | 0:05:30 | |

produced this wonderful collection of anatomical studies. | 0:05:30 | 0:05:35 | |

Meckel's meticulous and detailed work would help identify | 0:05:35 | 0:05:38 | |

the true nature of this animal. | 0:05:38 | 0:05:41 | |

Here... | 0:05:41 | 0:05:42 | |

..we can see his drawing of a male platypus, | 0:05:44 | 0:05:47 | |

showing clearly the claw. | 0:05:47 | 0:05:50 | |

Meckel also reported the existence of simple glands | 0:05:50 | 0:05:53 | |

beneath the thick fur of the female platypus, | 0:05:53 | 0:05:56 | |

glands that he suggested secreted milk. | 0:05:56 | 0:05:59 | |

There could be little doubt that these glands produced something. | 0:06:00 | 0:06:04 | |

But even then, several scientists doubted Meckel's claims, | 0:06:04 | 0:06:07 | |

and suggested rather desperately | 0:06:07 | 0:06:09 | |

that the glands secreted not milk but a lubricant. | 0:06:09 | 0:06:13 | |

Today we know that Meckel was right. | 0:06:13 | 0:06:15 | |

I was once able to use an optical probe | 0:06:15 | 0:06:18 | |

to peer into a platypus's burrow | 0:06:18 | 0:06:20 | |

and see a female platypus nurturing her single baby. | 0:06:20 | 0:06:24 | |

Yes. There it is. It's milk. | 0:06:26 | 0:06:30 | |

Milk is the perfect food. | 0:06:30 | 0:06:32 | |

It provides the growing youngster with everything it wants. | 0:06:32 | 0:06:37 | |

Only mammals produce milk. | 0:06:37 | 0:06:40 | |

In most mammals, of course, it comes from a nipple. | 0:06:40 | 0:06:43 | |

But in this very primitive mammal, | 0:06:43 | 0:06:46 | |

it simply oozes through the skin. | 0:06:46 | 0:06:48 | |

But 19th-century biologists had no such tricks to help them. | 0:06:50 | 0:06:55 | |

They had to unravel the strange biology of Australian mammals | 0:06:55 | 0:06:58 | |

from just a few shrivelled remains of long-dead specimens. | 0:06:58 | 0:07:02 | |

40 years after their discovery of the platypus, | 0:07:04 | 0:07:07 | |

a brilliant young anatomist - | 0:07:07 | 0:07:08 | |

who was to become a giant to 19th-century science - | 0:07:08 | 0:07:11 | |

joined the debate. | 0:07:11 | 0:07:13 | |

This is a statue of Richard Owen. | 0:07:13 | 0:07:16 | |

Owen was a formidable man. | 0:07:16 | 0:07:18 | |

The founding director of the Natural History Museum in Britain, | 0:07:18 | 0:07:22 | |

he was once described as having so much brain as to require two hats. | 0:07:22 | 0:07:26 | |

The platypus would become a central character in Owen's career. | 0:07:27 | 0:07:32 | |

His worked on this small creature | 0:07:32 | 0:07:33 | |

would help him secure election | 0:07:33 | 0:07:35 | |

to the prestigious Royal Society, | 0:07:35 | 0:07:37 | |

an exclusive group of scientists and thinkers. | 0:07:37 | 0:07:40 | |

Owen had an advantage over his European colleagues. | 0:07:41 | 0:07:45 | |

Australia was a British colony, | 0:07:46 | 0:07:49 | |

and Owen used his contacts | 0:07:49 | 0:07:51 | |

to supply him with specimens. | 0:07:51 | 0:07:52 | |

Eventually, two baby platypuses arrived | 0:07:55 | 0:07:58 | |

and it was obvious to him | 0:07:58 | 0:08:00 | |

that they would have no difficulty in suckling. | 0:08:00 | 0:08:03 | |

They'd not yet developed the bill | 0:08:04 | 0:08:06 | |

that would have made it awkward. | 0:08:06 | 0:08:08 | |

So he accepted the platypus babies, | 0:08:08 | 0:08:11 | |

like other mammal babies, | 0:08:11 | 0:08:12 | |

were indeed raised on milk. | 0:08:12 | 0:08:14 | |

But the biggest mystery of the platypus was still unsolved. | 0:08:17 | 0:08:21 | |

Did this animal lay eggs, | 0:08:22 | 0:08:24 | |

just like reptiles or birds, | 0:08:24 | 0:08:27 | |

or did it give birth to live young? | 0:08:27 | 0:08:29 | |

Owen was at the heart of that debate. | 0:08:30 | 0:08:32 | |

These jars contain the bodies of several platypus | 0:08:33 | 0:08:36 | |

that were shot and sent back here to the museum | 0:08:36 | 0:08:39 | |

for Richard Owen to examine. | 0:08:39 | 0:08:41 | |

His determination to prove whether or not they laid eggs | 0:08:41 | 0:08:44 | |

was going to cause the death of quite a number of platypus. | 0:08:44 | 0:08:49 | |

The Australian aborigines were absolutely clear they did lay eggs, | 0:08:49 | 0:08:53 | |

but that was not good enough for Owen. | 0:08:53 | 0:08:56 | |

He knew better than any Australian aboriginal. | 0:08:56 | 0:08:58 | |

He did concede that it might be | 0:08:59 | 0:09:01 | |

that the eggs were retained inside the body and hatched there, | 0:09:01 | 0:09:05 | |

so that the young were born live - | 0:09:05 | 0:09:07 | |

but that's as far as he'd go. | 0:09:07 | 0:09:09 | |

Eggs were also sent back. | 0:09:09 | 0:09:11 | |

Some of them were fake, | 0:09:11 | 0:09:13 | |

and some of them belonged to snakes. | 0:09:13 | 0:09:15 | |

It was going to be some decades | 0:09:15 | 0:09:17 | |

before the puzzle of the platypus | 0:09:17 | 0:09:19 | |

was finally solved. | 0:09:19 | 0:09:20 | |

The platypus now became embroiled | 0:09:23 | 0:09:25 | |

in the greatest scientific debate | 0:09:25 | 0:09:27 | |

of the Victorian era. | 0:09:27 | 0:09:29 | |

Did species evolve, | 0:09:29 | 0:09:31 | |

or were they created? | 0:09:31 | 0:09:33 | |

Darwin's Theory of Evolution | 0:09:33 | 0:09:35 | |

suggested that species could change over time, | 0:09:35 | 0:09:38 | |

so an intermediate form that laid eggs | 0:09:38 | 0:09:40 | |

but had fur like a mammal, was to be expected - | 0:09:40 | 0:09:44 | |

but that was too much of an stretch, | 0:09:44 | 0:09:46 | |

even for Owen's great brain. | 0:09:46 | 0:09:49 | |

In 1884, | 0:09:49 | 0:09:50 | |

more than 80 years after this first platypus specimen | 0:09:50 | 0:09:53 | |

had been examined by George Shaw, | 0:09:53 | 0:09:56 | |

William Hay Caldwell arrived in Australia | 0:09:56 | 0:09:59 | |

funded by a Royal Society scholarship. | 0:09:59 | 0:10:02 | |

One of his main aims was to solve the platypus egg question | 0:10:02 | 0:10:05 | |

once and for all. | 0:10:05 | 0:10:07 | |

After several months in Queensland | 0:10:07 | 0:10:09 | |

and with the help of the local aborigines, | 0:10:09 | 0:10:11 | |

he finally got the answer. | 0:10:11 | 0:10:13 | |

He shot a female platypus | 0:10:13 | 0:10:15 | |

soon after she had laid an egg in her nest burrow, | 0:10:15 | 0:10:19 | |

with a second egg about to emerge from her vent. | 0:10:19 | 0:10:22 | |

And they look like this. | 0:10:22 | 0:10:25 | |

It was, at last, visible evidence | 0:10:25 | 0:10:28 | |

that this animal did indeed lay eggs. | 0:10:28 | 0:10:31 | |

He sent a telegram to a scientific gathering in Montreal. | 0:10:31 | 0:10:34 | |

It was brief and to the point. | 0:10:34 | 0:10:36 | |

"Monotremes oviparous, | 0:10:36 | 0:10:39 | |

"ovum meroblastic." | 0:10:39 | 0:10:41 | |

These four words, to the scientifically initiated, | 0:10:41 | 0:10:45 | |

meant that the platypus laid eggs | 0:10:45 | 0:10:47 | |

and that the eggs consisted of an undivided large yolk, | 0:10:47 | 0:10:51 | |

just like a bird's egg. | 0:10:51 | 0:10:53 | |

The mystery was, at last, solved. | 0:10:53 | 0:10:56 | |

Richard Owen, who had refused to believe a mammal could lay an egg, | 0:10:59 | 0:11:03 | |

was by now 80 years old | 0:11:03 | 0:11:05 | |

and he was no longer held in the same esteem | 0:11:05 | 0:11:08 | |

as in the early part of his career. | 0:11:08 | 0:11:10 | |

The platypus had helped establish his reputation | 0:11:10 | 0:11:14 | |

but now the riddle of this creature's reproduction | 0:11:14 | 0:11:17 | |

had proved him wrong. | 0:11:17 | 0:11:18 | |

It's extraordinary to think | 0:11:20 | 0:11:21 | |

that this small animal fooled and confounded | 0:11:21 | 0:11:24 | |

many of the great scientific minds of 19th century Europe. | 0:11:24 | 0:11:28 | |

Not a hoax, | 0:11:28 | 0:11:29 | |

but a true curiosity, | 0:11:29 | 0:11:31 | |

and one like no other. | 0:11:31 | 0:11:33 | |

The egg-laying platypus was hardly believable | 0:11:36 | 0:11:38 | |

to Victorian researchers... | 0:11:38 | 0:11:40 | |

..but evolution has thrown up many unusual mating strategies | 0:11:41 | 0:11:45 | |

and, in the earlier part of the 20th century, | 0:11:45 | 0:11:48 | |

the anatomy of a particular amphibian started an argument that, | 0:11:48 | 0:11:52 | |

like the platypus, | 0:11:52 | 0:11:54 | |

led to accusations of forgery. | 0:11:54 | 0:11:56 | |

This is the curious tale of the midwife toad. | 0:11:56 | 0:12:00 | |

Midwife toads are not native to Britain. | 0:12:02 | 0:12:05 | |

They were introduced about a century ago and since then | 0:12:05 | 0:12:08 | |

have been slowly spreading over England. | 0:12:08 | 0:12:10 | |

Their natural home is Europe, | 0:12:10 | 0:12:13 | |

from Germany to Spain. | 0:12:13 | 0:12:15 | |

And in the 1920s, their mating habits caused a media sensation. | 0:12:15 | 0:12:22 | |

Investigations into the way the body of the male toad changed | 0:12:22 | 0:12:26 | |

according to its environment | 0:12:26 | 0:12:28 | |

led some to believe it might be possible | 0:12:28 | 0:12:31 | |

to breed a race of superhumans. | 0:12:31 | 0:12:34 | |

To understand why, | 0:12:34 | 0:12:36 | |

we must first know what makes the midwife toad so different | 0:12:36 | 0:12:39 | |

from any other frog or toad. | 0:12:39 | 0:12:41 | |

Amphibians were among the first backboned animals | 0:12:43 | 0:12:46 | |

to take to the land. | 0:12:46 | 0:12:47 | |

Since then, they've colonised most habitats, | 0:12:47 | 0:12:50 | |

from rainforests to deserts and mountains. | 0:12:50 | 0:12:54 | |

Despite spending much of their lives on land, | 0:12:55 | 0:12:57 | |

most frogs and toads need water to reproduce, | 0:12:57 | 0:13:00 | |

whether it be in a small vase plant or a large lake. | 0:13:00 | 0:13:04 | |

But mating in water is a slippery business. | 0:13:04 | 0:13:08 | |

Male toads, however, have a special adaptation. | 0:13:08 | 0:13:11 | |

Black warty swellings on their wrists, called nuptial pads, | 0:13:11 | 0:13:15 | |

which enable them to grip their partner securely during sex. | 0:13:15 | 0:13:19 | |

Once the female produces her eggs, | 0:13:19 | 0:13:21 | |

the male releases his sperm | 0:13:21 | 0:13:23 | |

and then lets go. His job is done. | 0:13:23 | 0:13:26 | |

But midwife toads are different. | 0:13:26 | 0:13:29 | |

The male does not have nuptial pads on his wrists. | 0:13:29 | 0:13:32 | |

And that's because he doesn't mate in water. | 0:13:33 | 0:13:37 | |

He mates on land. | 0:13:37 | 0:13:39 | |

The female produces her eggs | 0:13:39 | 0:13:41 | |

and then he takes them around his legs | 0:13:41 | 0:13:44 | |

with an action that has been compared | 0:13:44 | 0:13:47 | |

to a man trying to put on his trousers without using his hands. | 0:13:47 | 0:13:51 | |

And so it is the male toad that is the actual midwife, | 0:13:52 | 0:13:56 | |

not the female. | 0:13:56 | 0:13:58 | |

Midwife toads tend to live in places where open water is scarce. | 0:13:58 | 0:14:03 | |

Once the male has successfully | 0:14:04 | 0:14:06 | |

wrapped a string of eggs around his legs, | 0:14:06 | 0:14:08 | |

he usually hides under a rock, where it's suitably damp. | 0:14:08 | 0:14:12 | |

He may have as many as 150 eggs | 0:14:18 | 0:14:21 | |

and he hides away for up to two months while they develop. | 0:14:21 | 0:14:25 | |

Then, just before the eggs hatch, | 0:14:25 | 0:14:28 | |

he sets off to find water for his emerging tadpoles. | 0:14:28 | 0:14:31 | |

Now, the tadpoles of most frogs and toads | 0:14:34 | 0:14:37 | |

turn into the adult form within a matter of weeks, | 0:14:37 | 0:14:41 | |

but not so the midwife toad - it takes much, much longer. | 0:14:41 | 0:14:46 | |

In fact, sometimes, they may even overwinter | 0:14:46 | 0:14:50 | |

in the form of a tadpole, | 0:14:50 | 0:14:52 | |

which is why perhaps midwife toad tadpoles are such whoppers! | 0:14:52 | 0:14:56 | |

Frogs and toads are widely used in biological studies, | 0:14:58 | 0:15:02 | |

because they're easy to keep | 0:15:02 | 0:15:03 | |

and the different stages of their life cycles are easy to observe. | 0:15:03 | 0:15:08 | |

So it's no surprise that the unusual behaviour | 0:15:08 | 0:15:10 | |

of the midwife toad should attract the attention of many biologists. | 0:15:10 | 0:15:14 | |

One was an Austrian scientist called Paul Kammerer, | 0:15:16 | 0:15:19 | |

who worked in Vienna in the early part of the 20th century. | 0:15:19 | 0:15:23 | |

And his discoveries quickly brought him great fame. | 0:15:23 | 0:15:26 | |

But the toad would become a curse | 0:15:28 | 0:15:31 | |

that would haunt him until the end of his life. | 0:15:31 | 0:15:34 | |

Kammerer was greatly influenced | 0:15:36 | 0:15:38 | |

by the great French zoologist Jean Baptiste Lamarck, | 0:15:38 | 0:15:41 | |

who in 1799 published his theory that characteristics acquired | 0:15:41 | 0:15:46 | |

by an animal during its life could be inherited by its offspring. | 0:15:46 | 0:15:51 | |

That a giraffe, for example, | 0:15:51 | 0:15:53 | |

reaching upwards to nibble the topmost shoots of trees, would | 0:15:53 | 0:15:57 | |

over time lengthen its neck muscles and that this increase would then be | 0:15:57 | 0:16:02 | |

inherited by its offspring, and so on, for generation after generation. | 0:16:02 | 0:16:07 | |

Lamarck's theory was largely rejected after Charles Darwin | 0:16:08 | 0:16:12 | |

proposed a different mechanism for evolution, | 0:16:12 | 0:16:15 | |

based on changes to an animal's genetic make-up. | 0:16:15 | 0:16:18 | |

Kammerer was keen to prove that Lamarck was right after all. | 0:16:19 | 0:16:24 | |

But giraffes are not the ideal experimental animal, | 0:16:24 | 0:16:27 | |

so he needed one he could keep in a lab and that would | 0:16:27 | 0:16:30 | |

reproduce quickly, and his attention fell on the midwife toad. | 0:16:30 | 0:16:34 | |

Kammerer became fascinated | 0:16:35 | 0:16:37 | |

with the unusual nature of the midwife toad's reproduction. | 0:16:37 | 0:16:41 | |

Why did males, like this one, carry eggs around his legs? | 0:16:41 | 0:16:46 | |

And could this be changed? | 0:16:46 | 0:16:48 | |

He wondered if their biology might be related | 0:16:48 | 0:16:51 | |

to their unnatural environment, which is largely arid. | 0:16:51 | 0:16:55 | |

Kammerer decided to see what would happen if he kept the toads | 0:16:55 | 0:16:58 | |

in a warm, humid tank with access to pools of cool water. | 0:16:58 | 0:17:02 | |

His work with the toads would last many years | 0:17:03 | 0:17:06 | |

and involve several generations, but eventually, he noticed changes. | 0:17:06 | 0:17:11 | |

Some male toads abandoned carrying the eggs | 0:17:11 | 0:17:14 | |

and instead, the females laid them directly in water. | 0:17:14 | 0:17:18 | |

Over several generations, | 0:17:20 | 0:17:22 | |

Kammerer had managed to change the midwife toad | 0:17:22 | 0:17:26 | |

from being a land-breeding animal to one that bred in water. | 0:17:26 | 0:17:30 | |

But the most extraordinary discovery | 0:17:30 | 0:17:33 | |

came as he continued breeding these toads. | 0:17:33 | 0:17:36 | |

He noticed that the wrists of some of the males | 0:17:36 | 0:17:40 | |

developed warty-looking structures, | 0:17:40 | 0:17:42 | |

just like the nuptial pads of other frogs and toads, which are normally | 0:17:42 | 0:17:46 | |

used by males to grip females when fertilising her eggs. | 0:17:46 | 0:17:50 | |

His work suggested that somehow, by altering | 0:17:51 | 0:17:54 | |

the environment in which they lived, a toad's body could be changed. | 0:17:54 | 0:17:58 | |

And that change was then passed on to future generations. | 0:17:58 | 0:18:02 | |

Kammerer's work was taking place at the end of the First World War | 0:18:04 | 0:18:07 | |

and political movements on the left and the right | 0:18:07 | 0:18:10 | |

were then keen to exploit scientific discoveries. | 0:18:10 | 0:18:13 | |

Despite his subject being a small toad, | 0:18:13 | 0:18:16 | |

some saw a opportunity to extend his findings beyond the laboratory. | 0:18:16 | 0:18:21 | |

He was hailed as a second Darwin in the New York Times. | 0:18:23 | 0:18:27 | |

Some newspapers got carried away | 0:18:27 | 0:18:28 | |

and suggested that Kammerer's discoveries could apply to humans. | 0:18:28 | 0:18:32 | |

His work could help, in other words, to breed a race of superhumans. | 0:18:32 | 0:18:38 | |

Whether he liked it or not, Kammerer was now in the spotlight. | 0:18:38 | 0:18:41 | |

He set off on a lecture tour across Europe and America. | 0:18:42 | 0:18:46 | |

In Cambridge, the Professor of Zoology hailed his achievements | 0:18:46 | 0:18:50 | |

and put one of Kammerer's toads on display. | 0:18:50 | 0:18:52 | |

But not everyone was convinced. | 0:18:54 | 0:18:56 | |

An American zoologist by the name of GK Noble wrote a damning article | 0:18:56 | 0:19:00 | |

in the prestigious scientific journal Nature. | 0:19:00 | 0:19:03 | |

Noble examined one of Kammerer's toads and declared that | 0:19:04 | 0:19:07 | |

its black nuptial pads were fakes, produced by injecting a black dye. | 0:19:07 | 0:19:12 | |

Kammerer denied this. | 0:19:13 | 0:19:15 | |

Someone, he said, had interfered with his specimens | 0:19:15 | 0:19:17 | |

and was trying to ruin him. | 0:19:17 | 0:19:19 | |

But the damage to his name was done. | 0:19:20 | 0:19:22 | |

Six weeks after the Nature article accusing him of forgery, | 0:19:23 | 0:19:27 | |

Kammerer wrote a letter to another leading scientific journal. | 0:19:27 | 0:19:31 | |

This is an extract of what it said. | 0:19:31 | 0:19:34 | |

"On the basis of this state of affairs, I dare not - | 0:19:35 | 0:19:39 | |

"although I myself have had no part | 0:19:39 | 0:19:41 | |

"in these falsifications of my prior specimens - | 0:19:41 | 0:19:45 | |

"any longer consider myself a proper man to accept your call. | 0:19:45 | 0:19:50 | |

"I see that I am also not in a position to endure | 0:19:50 | 0:19:53 | |

"this wrecking of my life's work and I hope I shall gather together | 0:19:53 | 0:19:57 | |

"enough courage and strength to put an end of my wrecked life tomorrow." | 0:19:57 | 0:20:02 | |

Soon after writing that letter, | 0:20:03 | 0:20:06 | |

he walked into the hills around his home and shot himself. | 0:20:06 | 0:20:10 | |

Whether or not Kammerer's suicide was purely down to the fallout | 0:20:10 | 0:20:14 | |

from his midwife toad experiments, we can't be sure. | 0:20:14 | 0:20:18 | |

There were many other problems in his personal life. | 0:20:18 | 0:20:21 | |

But there can be little doubt that the scandal surrounding his work | 0:20:21 | 0:20:25 | |

would've weighed heavily on his mind. | 0:20:25 | 0:20:27 | |

Since Kammerer's death, a specimen of male midwife toad | 0:20:28 | 0:20:32 | |

with nuptial pads has been found in the wild. | 0:20:32 | 0:20:36 | |

Some scientists now believe that environmental influences | 0:20:36 | 0:20:40 | |

CAN change the way some genes behave, | 0:20:40 | 0:20:43 | |

and that these changes can indeed be passed on to the next generation. | 0:20:43 | 0:20:48 | |

Perhaps midwife toads possess the gene to grow these structures, | 0:20:48 | 0:20:53 | |

but it's only switched on in certain situations. | 0:20:53 | 0:20:56 | |

Does this prove Kammerer was right? | 0:20:56 | 0:20:59 | |

No-one has been able to repeat | 0:20:59 | 0:21:01 | |

Kammerer's experiments with midwife toads. | 0:21:01 | 0:21:03 | |

So we don't know for sure if he falsified his findings or whether | 0:21:03 | 0:21:07 | |

he had stumbled upon a quirk of inheritance ahead of its time | 0:21:07 | 0:21:11 | |

and beyond the understanding of scientists of his era. | 0:21:11 | 0:21:14 | |

What is certain is that the nature | 0:21:14 | 0:21:17 | |

of how species inherit their characteristics | 0:21:17 | 0:21:20 | |

is more complex than he or others at the time originally thought. | 0:21:20 | 0:21:24 | |

The curious lives of the midwife toad and the duckbilled platypus | 0:21:26 | 0:21:31 | |

perplexed and wrong-footed science for some considerable time. | 0:21:31 | 0:21:35 | |

But in the end, both of these creatures helped us | 0:21:35 | 0:21:38 | |

to better understand the way animals evolve. | 0:21:38 | 0:21:42 |