Animal House Natural World

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Animal House. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

I'm fascinated by the glimpses we sometimes get | 0:00:14 | 0:00:17 | |

into an animal's hidden world. | 0:00:17 | 0:00:19 | |

Over the years, I've found different ways to peer inside. | 0:00:22 | 0:00:27 | |

They say, if you want to understand people, look in their houses. | 0:00:49 | 0:00:54 | |

I think the same may be true for wildlife. | 0:00:58 | 0:01:01 | |

I've never been invited in | 0:01:05 | 0:01:07 | |

and, on occasions, I've not been entirely welcome. | 0:01:07 | 0:01:11 | |

I think that was pretty clear. Oh, dear! | 0:01:15 | 0:01:18 | |

Despite setbacks, I've seen skilled builders... | 0:01:22 | 0:01:26 | |

I've discovered squatters and burglars... | 0:01:28 | 0:01:30 | |

I've noticed interior decoration... | 0:01:32 | 0:01:34 | |

I've found storerooms and air conditioning | 0:01:35 | 0:01:39 | |

and even en-suite bathrooms... | 0:01:39 | 0:01:42 | |

I've visited animal cities | 0:01:42 | 0:01:45 | |

and huge communities. | 0:01:45 | 0:01:47 | |

Wild homemakers are special creatures, | 0:01:49 | 0:01:53 | |

more like us, trying to keep out the wilder wildlife. | 0:01:53 | 0:01:58 | |

Peering into an animal's house can tell you so much about them. | 0:02:04 | 0:02:09 | |

It's a window into their private dramas | 0:02:11 | 0:02:14 | |

and the intimate stories we rarely see. | 0:02:14 | 0:02:16 | |

Most of us are indoor creatures. | 0:02:27 | 0:02:32 | |

Houses have ended our wild days. | 0:02:32 | 0:02:34 | |

Yet, we forget that animals build many more houses than we do. | 0:02:36 | 0:02:41 | |

And they've been doing it for much longer. | 0:02:42 | 0:02:46 | |

We think we alone invented building materials, | 0:02:46 | 0:02:52 | |

but animals have done so, as well. | 0:02:52 | 0:02:54 | |

Scaled up to our size, termite mounds would be almost a mile high. | 0:02:55 | 0:03:00 | |

Animals have an eye for beauty | 0:03:04 | 0:03:06 | |

and so do we. | 0:03:06 | 0:03:08 | |

Our homes reveal a lot about us, | 0:03:11 | 0:03:15 | |

but this is the animals' story. | 0:03:15 | 0:03:18 | |

In North America lives probably the most ambitious | 0:03:20 | 0:03:24 | |

animal builder in the world. | 0:03:24 | 0:03:26 | |

Up to a mile or so of river is taken over by a single family of beavers. | 0:03:32 | 0:03:37 | |

Dams flood the landscape, creating ponds | 0:03:37 | 0:03:42 | |

and canals that cover many acres. | 0:03:42 | 0:03:44 | |

At the centre is their lodge - | 0:03:47 | 0:03:50 | |

a defensive moat surrounds a sturdy castle, | 0:03:50 | 0:03:53 | |

made of serious building materials. | 0:03:53 | 0:03:56 | |

A beaver can gnaw through a tree in an hour or two. | 0:04:03 | 0:04:08 | |

He often stops halfway and lets the wind do the rest. | 0:04:08 | 0:04:12 | |

His teeth are reinforced with iron, which turns them orange. | 0:04:12 | 0:04:18 | |

The teeth wear down a millimetre a day, | 0:04:23 | 0:04:26 | |

but grow ten times faster than our fingernails. | 0:04:26 | 0:04:30 | |

Even metre lengths are too heavy to drag over land, | 0:04:32 | 0:04:35 | |

but by flooding the area, the beavers can easily move the logs. | 0:04:35 | 0:04:39 | |

Each dam needs about 50 tons and can be hundreds of metres long. | 0:04:41 | 0:04:45 | |

Mud is used to seal any leaks. | 0:04:47 | 0:04:49 | |

Everything has to be ready for winter. | 0:04:51 | 0:04:54 | |

Of the beaver's rural community, most have left or are hidden, | 0:05:08 | 0:05:12 | |

housebound, at this time of year. | 0:05:12 | 0:05:15 | |

The only sign is a ripple of heat from a chimney, | 0:05:16 | 0:05:19 | |

identifying the beavers' lodge. | 0:05:19 | 0:05:21 | |

Inside, special cameras reveal new young, | 0:05:25 | 0:05:28 | |

born early, thanks to the protection of metre-thick walls, | 0:05:28 | 0:05:33 | |

sealed with mud and straw. | 0:05:33 | 0:05:35 | |

It's been minus 20 outside and still didn't freeze in here. | 0:05:35 | 0:05:40 | |

The chimney is open, as now it gets too hot. | 0:05:40 | 0:05:45 | |

The only way in and out | 0:05:48 | 0:05:50 | |

is to swim underwater, but that doesn't discourage a muskrat. | 0:05:50 | 0:05:55 | |

Voles, mice and insects also find refuge here. | 0:05:58 | 0:06:02 | |

The lodge has lodgers. | 0:06:04 | 0:06:05 | |

We never saw the landlords object to the muskrat, | 0:06:08 | 0:06:12 | |

which is more than can be said for the cameras, | 0:06:12 | 0:06:15 | |

which they soon censored! | 0:06:15 | 0:06:17 | |

Outside, the itinerant and the homeless | 0:06:25 | 0:06:29 | |

must wish they were somewhere safe and warm. | 0:06:29 | 0:06:32 | |

WOLF HOWLS | 0:06:32 | 0:06:37 | |

Solid walls and underwater doors | 0:06:53 | 0:06:56 | |

are not the only ways to try and keep the outside out. | 0:06:56 | 0:07:00 | |

Prairie dogs live in an underground colony called a dog town, | 0:07:04 | 0:07:09 | |

which can stretch over the horizon. | 0:07:09 | 0:07:13 | |

The town is divided into coteries, extended families, | 0:07:15 | 0:07:19 | |

living behind a volcano-shaped front door, | 0:07:19 | 0:07:22 | |

and with an acre or so of manicured lawn to provide food. | 0:07:22 | 0:07:25 | |

Prairie dogs themselves may seem like fat vegetarian meerkats, | 0:07:35 | 0:07:40 | |

but they're actually squirrels... | 0:07:40 | 0:07:43 | |

that bark. | 0:07:43 | 0:07:46 | |

And they don't like visitors. | 0:07:46 | 0:07:48 | |

There's a father in charge, | 0:07:51 | 0:07:52 | |

several wives, and different generations of youngsters. | 0:07:52 | 0:07:57 | |

Each family rarely goes beyond their garden boundaries, | 0:07:57 | 0:08:02 | |

and they all work together on their house. | 0:08:02 | 0:08:06 | |

Time is spent on home improvements and household chores. | 0:08:06 | 0:08:11 | |

The raised entrances are watchtowers, | 0:08:14 | 0:08:17 | |

but are also chimneys, and draw air through the burrows. | 0:08:17 | 0:08:21 | |

The lower-level holes are fresh air intakes. | 0:08:22 | 0:08:25 | |

Inside each family home may be 30 metres of tunnelling | 0:08:28 | 0:08:32 | |

with many different rooms. | 0:08:32 | 0:08:34 | |

There are sleeping chambers, where they spend most of the winter. | 0:08:37 | 0:08:40 | |

Some even have an adjacent lavatory room. | 0:08:40 | 0:08:43 | |

There are storage rooms, anti-flooding features, | 0:08:43 | 0:08:46 | |

and escape hatches. | 0:08:46 | 0:08:48 | |

It's warm in winter and cool in summer. | 0:08:48 | 0:08:51 | |

It's an estate agent's dream. | 0:08:51 | 0:08:54 | |

The pups, at a few days old, are tiny, bald and blind. | 0:08:59 | 0:09:05 | |

Their mother will stay with them in a special nursery, | 0:09:05 | 0:09:08 | |

feeding them and sorting out bedding. | 0:09:08 | 0:09:11 | |

Even at birth, prairie dogs are clearly builders, | 0:09:11 | 0:09:15 | |

with shovel-shaped heads, cylindrical bodies, | 0:09:15 | 0:09:18 | |

and digger's claws. | 0:09:18 | 0:09:20 | |

With so many corridors, | 0:09:25 | 0:09:27 | |

it's possible that one might lead by mistake into a neighbour's house, | 0:09:27 | 0:09:31 | |

and the neighbours could be burrowing owls. | 0:09:31 | 0:09:35 | |

In the dark, | 0:09:36 | 0:09:38 | |

the startled owls give a good impersonation of a rattlesnake. | 0:09:38 | 0:09:43 | |

OWL HISSES MENACINGLY | 0:09:44 | 0:09:48 | |

The owls have young, too, | 0:10:00 | 0:10:02 | |

hatched in an abandoned part of the prairie dog burrow. | 0:10:02 | 0:10:06 | |

They are, in effect, harmless squatters. | 0:10:06 | 0:10:09 | |

The dog town is full of freeloaders. | 0:10:12 | 0:10:16 | |

Hares and snakes find homes in this mixed neighbourhood. | 0:10:16 | 0:10:21 | |

Dangerous characters, like black-footed ferrets | 0:10:23 | 0:10:26 | |

and swift foxes, live in old burrows. | 0:10:26 | 0:10:28 | |

Overall, wildlife increases wherever animals build homes, | 0:10:30 | 0:10:35 | |

whether the builders like it or not. | 0:10:35 | 0:10:38 | |

Maybe as a response, | 0:10:46 | 0:10:48 | |

prairie dogs have a community police service. | 0:10:48 | 0:10:52 | |

Family members takes turns watching out for predators. | 0:10:52 | 0:10:56 | |

A prairie dog calls "Eagle!". | 0:11:04 | 0:11:07 | |

Families for up to half a mile around run for cover. | 0:11:07 | 0:11:11 | |

The whole neighbourhood benefits. | 0:11:11 | 0:11:14 | |

The prairie dogs even have different calls for different predators. | 0:11:19 | 0:11:24 | |

"Coyote" sends them down their burrows, | 0:11:24 | 0:11:28 | |

but calling "Badger" needs a different response, | 0:11:28 | 0:11:31 | |

as badgers can dig, | 0:11:31 | 0:11:34 | |

so the dogs watch them nervously from the surface. | 0:11:34 | 0:11:38 | |

Their calls may include information on size, | 0:11:38 | 0:11:41 | |

direction and speed, even colour. | 0:11:41 | 0:11:45 | |

It's one of the most sophisticated animal languages ever studied | 0:11:45 | 0:11:48 | |

and has arisen in response to the predators | 0:11:48 | 0:11:51 | |

that are drawn to animal houses. | 0:11:51 | 0:11:53 | |

Living close to your neighbour can provide some protection. | 0:11:57 | 0:12:01 | |

The problem is, it can also attract more predators. | 0:12:01 | 0:12:05 | |

Southern carmine bee-eaters catch the eye of a hungry fish eagle. | 0:12:10 | 0:12:15 | |

Predators have a major influence on how houses are built. | 0:12:27 | 0:12:32 | |

Here, along the Luangwa River in Africa, | 0:12:32 | 0:12:35 | |

sandy cliffs are one of the few places out of reach | 0:12:35 | 0:12:38 | |

of eagles, lizards, and monkeys. | 0:12:38 | 0:12:40 | |

A bee-eater pair takes turns digging the burrow | 0:12:45 | 0:12:48 | |

with their beaks and feet. | 0:12:48 | 0:12:50 | |

The centre of the colony is safer from predators than the edge, | 0:12:58 | 0:13:03 | |

so the birds nest closely together in the middle. | 0:13:03 | 0:13:07 | |

The result is evenly-spaced lines of townhouses. | 0:13:07 | 0:13:10 | |

But, the denser the colony, | 0:13:13 | 0:13:15 | |

the more attention it gets. | 0:13:15 | 0:13:17 | |

The bee-eaters unite, screaming at the intruder. | 0:13:20 | 0:13:24 | |

Noisy neighbours are a life-saver. | 0:13:28 | 0:13:30 | |

On every continent, animals converge to build homes together. | 0:13:39 | 0:13:43 | |

A quarter of a million Socotra cormorants | 0:13:48 | 0:13:50 | |

arrive on desert islands off Arabia | 0:13:50 | 0:13:53 | |

to build simple mounds in the sand away from predators. | 0:13:53 | 0:13:58 | |

Some debris is favoured for the nest, other bits rejected. | 0:13:58 | 0:14:01 | |

The bird next door tries to steal from the collection. | 0:14:05 | 0:14:08 | |

The chicks, when they hatch, | 0:14:24 | 0:14:25 | |

must be protected from the neighbours' lethal beaks, | 0:14:25 | 0:14:29 | |

so nests are built just out of pecking range. | 0:14:29 | 0:14:33 | |

They end up building near inch-perfect | 0:14:38 | 0:14:41 | |

geometric plots in their thousands. | 0:14:41 | 0:14:44 | |

But the greatest animal houses in the world are caves. | 0:14:56 | 0:15:02 | |

3.5 million bats live in this cave in Borneo. | 0:15:07 | 0:15:11 | |

Each evening, they leave the safety of their home | 0:15:16 | 0:15:19 | |

to feed on insects in the surrounding forest. | 0:15:19 | 0:15:22 | |

They gather outside the city gate in a defensive whirlwind. | 0:15:27 | 0:15:31 | |

The swirling commuters are running a gauntlet | 0:15:35 | 0:15:39 | |

of bat hawks and peregrine falcons. | 0:15:39 | 0:15:42 | |

The birds of prey grab anything that tries to go it alone. | 0:15:42 | 0:15:45 | |

As the nightshift leaves home, | 0:15:55 | 0:15:58 | |

the dayshift is returning. | 0:15:58 | 0:16:00 | |

Cave swiftlets navigate into dark caverns by echolocation, | 0:16:02 | 0:16:06 | |

like a bat, almost the only birds to do so. | 0:16:06 | 0:16:09 | |

They make powerful clicks, | 0:16:11 | 0:16:13 | |

and listen to the sound bouncing off the walls. | 0:16:13 | 0:16:16 | |

Male swiftlets choose tiny high-rise ledges, | 0:16:28 | 0:16:32 | |

maybe 100 metres above the cavern floor. | 0:16:32 | 0:16:36 | |

They share the space | 0:16:36 | 0:16:38 | |

with specialist spiders, | 0:16:38 | 0:16:40 | |

cave centipedes | 0:16:40 | 0:16:41 | |

and bats. | 0:16:41 | 0:16:43 | |

The bats have left a stinking mountain of droppings | 0:16:44 | 0:16:47 | |

over 30 metres high. | 0:16:47 | 0:16:48 | |

It's the biggest indoor lavatory in the world. | 0:16:50 | 0:16:53 | |

This is a cave with double the population of Manhattan | 0:16:55 | 0:16:59 | |

and no plumbing. | 0:16:59 | 0:17:01 | |

And it's crawling with cockroaches. | 0:17:03 | 0:17:05 | |

The cockroaches feed on the droppings, | 0:17:07 | 0:17:09 | |

and anything else that falls to the floor. | 0:17:09 | 0:17:12 | |

The best ledges have to be fought for, | 0:17:18 | 0:17:22 | |

and a male battles over real estate in the pitch blackness. | 0:17:22 | 0:17:27 | |

Swallows and martins normally use mud, | 0:17:29 | 0:17:32 | |

but the swiftlets make their own walls. | 0:17:32 | 0:17:35 | |

It's a sort of gluey saliva, which they attach to the rock, | 0:17:35 | 0:17:38 | |

and build up, layer by layer, making a tiny egg-cup. | 0:17:38 | 0:17:42 | |

It can be weeks of painstaking work. | 0:17:42 | 0:17:45 | |

The saliva hardens | 0:17:57 | 0:17:58 | |

into one of the most extraordinary animal houses in the world, | 0:17:58 | 0:18:03 | |

a crystal chalice. | 0:18:03 | 0:18:05 | |

The nests become as crowded as closely-packed apartments. | 0:18:15 | 0:18:19 | |

Woven-in feathers darken the nests, | 0:18:19 | 0:18:22 | |

but single white eggs glow in the lights. | 0:18:22 | 0:18:25 | |

For generations, this cave has been one of the safest homes. | 0:18:31 | 0:18:36 | |

That is, until a new predator found it. | 0:18:37 | 0:18:40 | |

Men are here | 0:18:46 | 0:18:48 | |

to collect a culinary delicacy for the famous bird's nest soup. | 0:18:48 | 0:18:52 | |

The saliva is full of proteins and minerals, | 0:18:55 | 0:18:58 | |

but apparently the nests don't taste of anything. | 0:18:58 | 0:19:02 | |

The little homes are worth thousands of dollars a basketful. | 0:19:04 | 0:19:08 | |

The legal trade alone in bird's nest soup | 0:19:08 | 0:19:13 | |

is worth about half a billion dollars. | 0:19:13 | 0:19:15 | |

Inevitably, wild cave swiftlets are in decline. | 0:19:16 | 0:19:20 | |

Saliva is an extraordinary building material, | 0:19:27 | 0:19:30 | |

but perhaps the most remarkable of all is silk. | 0:19:30 | 0:19:34 | |

The coiled threads of protein are famously strong and light... | 0:19:44 | 0:19:48 | |

..which is why other animals steal them. | 0:19:50 | 0:19:53 | |

A bronzy hermit hummingbird in Central America collects cobwebs. | 0:19:55 | 0:20:01 | |

With the silk threads, she weaves a pocket, anchored under a leaf. | 0:20:05 | 0:20:10 | |

The leaf keeps out the rain, and prying eyes. | 0:20:10 | 0:20:13 | |

Camouflage is all the defence she needs. | 0:20:13 | 0:20:16 | |

A lethal trap has become a different sort of home - | 0:20:27 | 0:20:30 | |

a cradle. | 0:20:30 | 0:20:32 | |

Baby hummingbirds grow up suspended in silk | 0:20:33 | 0:20:37 | |

and fed on nectar. | 0:20:37 | 0:20:39 | |

The second-hand web can carry the young and the parent birds, | 0:20:49 | 0:20:53 | |

though it was originally made only to catch a fly. | 0:20:53 | 0:20:56 | |

Even ordinary building materials can be transformed | 0:21:01 | 0:21:05 | |

by the skill of the builder. | 0:21:05 | 0:21:07 | |

A female red-rumped cacique in South America | 0:21:10 | 0:21:13 | |

ties palm leaf strands into loops and knots. | 0:21:13 | 0:21:16 | |

The mother caciques choose the nest site, | 0:21:29 | 0:21:33 | |

build and bicker over space. | 0:21:33 | 0:21:36 | |

The architectural blueprint is instinctive, | 0:21:41 | 0:21:44 | |

but she adapts and refines the basic plan, | 0:21:44 | 0:21:47 | |

and her skill improves with practice. | 0:21:47 | 0:21:50 | |

The foundations are made first, | 0:21:50 | 0:21:53 | |

then a loop, the entrance to the nest. | 0:21:53 | 0:21:57 | |

The door is extended into a tube, | 0:21:58 | 0:22:01 | |

like a sock about 40 centimetres long. | 0:22:01 | 0:22:04 | |

After up to three weeks' work, a nest is finished at the bottom. | 0:22:04 | 0:22:08 | |

You can't leave your handiwork for long, | 0:22:12 | 0:22:15 | |

or your older and cannier neighbours try and pull it apart | 0:22:15 | 0:22:18 | |

and steal your building material. | 0:22:18 | 0:22:21 | |

The final nest is this shape because there are egg thieves. | 0:22:34 | 0:22:38 | |

This is a Toco toucan. | 0:22:40 | 0:22:43 | |

The nest tube must be long enough | 0:22:43 | 0:22:46 | |

so that predators can't see the chicks or reach the bottom. | 0:22:46 | 0:22:49 | |

Over the generations, caciques have extended their nests | 0:22:49 | 0:22:53 | |

to keep the young safe. | 0:22:53 | 0:22:55 | |

The toucan is trying an attack through the side of a nest. | 0:23:00 | 0:23:03 | |

They have an unlikely ally. | 0:23:08 | 0:23:10 | |

Casiques often nest near bees and wasps. | 0:23:10 | 0:23:14 | |

The chicks are safe, | 0:23:23 | 0:23:25 | |

though the nest seems to have acquired a new window. | 0:23:25 | 0:23:28 | |

It looks like the parent may have to get materials for repair work. | 0:23:31 | 0:23:35 | |

Building supplies are so important | 0:23:40 | 0:23:43 | |

to some animals that, in places, the materials themselves | 0:23:43 | 0:23:46 | |

have taken on a particular significance. | 0:23:46 | 0:23:49 | |

Flightless cormorants build their nests from seaweed. | 0:23:51 | 0:23:54 | |

On the shores of the Galapagos Islands, there isn't much else. | 0:23:54 | 0:23:58 | |

It seems this is as much about their relationship, | 0:24:07 | 0:24:11 | |

as building the nest. | 0:24:11 | 0:24:13 | |

They're like newlyweds cooing over paint swatches. | 0:24:13 | 0:24:18 | |

Colour is important, and texture, | 0:24:23 | 0:24:25 | |

and the females seem to weigh up each gift. | 0:24:25 | 0:24:28 | |

Occasional exotic offerings - a living sea urchin, | 0:24:31 | 0:24:35 | |

or a new shade of seaweed - | 0:24:35 | 0:24:37 | |

are brought to the nest, and sometimes rejected. | 0:24:37 | 0:24:41 | |

A gift that walks away is of no use. | 0:24:41 | 0:24:44 | |

And size certainly doesn't impress her. | 0:24:48 | 0:24:50 | |

The drying seaweed means more to the cormorants | 0:24:57 | 0:25:00 | |

than mere construction materials. | 0:25:00 | 0:25:02 | |

A nest becomes a special place, | 0:25:05 | 0:25:08 | |

to be defended from curious visitors... | 0:25:08 | 0:25:11 | |

..and a perfect home for the eggs. | 0:25:14 | 0:25:17 | |

We don't know exactly what they think or feel, | 0:25:17 | 0:25:22 | |

but some scientists believe the effort | 0:25:22 | 0:25:24 | |

seems to draw them closer together. | 0:25:24 | 0:25:26 | |

The chick benefits from the parents' commitment | 0:25:38 | 0:25:42 | |

to making the perfect home. | 0:25:42 | 0:25:44 | |

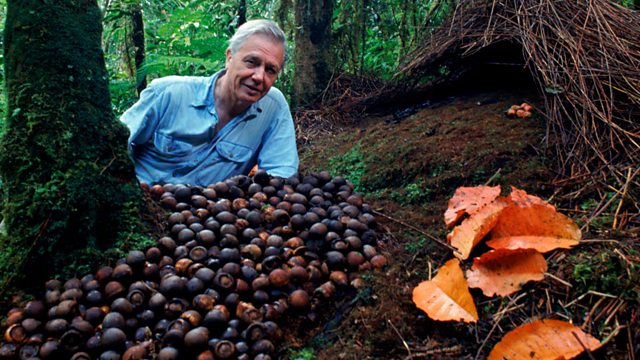

The ultimate example of an animal that builds a palace | 0:25:48 | 0:25:52 | |

to win round a mate can be found in the forests of New Guinea. | 0:25:52 | 0:25:55 | |

This metre-wide woven wigwam is a seduction pad | 0:26:08 | 0:26:12 | |

and is all about show. | 0:26:12 | 0:26:14 | |

Carefully arranged flowers and fruits | 0:26:17 | 0:26:19 | |

are placed in piles on manicured moss. | 0:26:19 | 0:26:22 | |

Smaller treasures are towards the back, | 0:26:23 | 0:26:25 | |

to make the bower seem bigger, a trick interior designers use. | 0:26:25 | 0:26:30 | |

Yet the male Vogelkop bowerbird himself is modest, even drab. | 0:26:40 | 0:26:45 | |

It may take many years to become a proficient enough | 0:26:45 | 0:26:50 | |

house builder to reach this stage. | 0:26:50 | 0:26:53 | |

If he sees a twig out of place, he'll push it in or remove it. | 0:26:55 | 0:27:00 | |

His architectural eye is unique. | 0:27:07 | 0:27:10 | |

His rival neighbours each have different colour schemes, | 0:27:10 | 0:27:14 | |

or floor designs or decorations. | 0:27:14 | 0:27:16 | |

This particular male is going through a red phase. | 0:27:16 | 0:27:20 | |

The flowers are changed regularly | 0:27:29 | 0:27:32 | |

and the berries must be perfectly arranged, even the right way up. | 0:27:32 | 0:27:35 | |

The floor is a challenge. | 0:27:39 | 0:27:40 | |

Roots grow through the moss and have to be tackled. | 0:27:40 | 0:27:44 | |

What he can't remove, he sweeps under the carpet. | 0:27:44 | 0:27:47 | |

A rival male is singing. | 0:28:05 | 0:28:06 | |

He must respond. | 0:28:11 | 0:28:13 | |

We see perhaps now why the bower is the shape it is. | 0:28:13 | 0:28:17 | |

It's a concert platform and the arch may help project his voice. | 0:28:17 | 0:28:23 | |

He ends with a little dance. | 0:28:28 | 0:28:31 | |

The audience has arrived. | 0:28:33 | 0:28:34 | |

She seems interested, but he has disappeared. | 0:28:34 | 0:28:39 | |

It is crucial in bowerbird courtship that he remains hidden. | 0:28:39 | 0:28:43 | |

His house has to coax her in. | 0:28:43 | 0:28:46 | |

Only when she is brought to a state of ecstasy over his decor | 0:28:56 | 0:28:59 | |

does he dash out and try to mate. | 0:28:59 | 0:29:03 | |

It's not entirely successful. Maybe she wasn't ready for his appearance. | 0:29:07 | 0:29:13 | |

Or maybe his flowers or his floor weren't up to scratch. | 0:29:13 | 0:29:18 | |

It's most frustrating. | 0:29:18 | 0:29:21 | |

Perhaps he will tempt her back and maybe next time, | 0:29:31 | 0:29:33 | |

the bower will be looking at its best. | 0:29:33 | 0:29:37 | |

Home decoration can, occasionally, | 0:29:42 | 0:29:45 | |

be about more than impressing the perfect partner. | 0:29:45 | 0:29:48 | |

The burrowing owls in prairie dog town have a strange take | 0:29:51 | 0:29:55 | |

on suitable suburban decor. | 0:29:55 | 0:29:58 | |

Their landlords, the prairie dogs, | 0:29:58 | 0:30:01 | |

would not approve of this innovation. | 0:30:01 | 0:30:04 | |

What burrowing owls like is what the buffalo leave behind. | 0:30:04 | 0:30:09 | |

They collect dung. | 0:30:11 | 0:30:13 | |

The owl places the dung carefully around his front door. | 0:30:18 | 0:30:22 | |

The burrowing owl chicks don't seem impressed by the collection | 0:30:22 | 0:30:27 | |

of poop on the stoop. | 0:30:27 | 0:30:29 | |

This is not how most wise animals treat their own doorsteps. | 0:30:29 | 0:30:35 | |

In fact, this extraordinary bit of decoration | 0:30:49 | 0:30:53 | |

is a trap for beetles, particularly dung beetles. | 0:30:53 | 0:30:58 | |

The beetles find dung by smell. | 0:30:58 | 0:31:02 | |

It is, to them, building material and food, rolled into one. | 0:31:02 | 0:31:07 | |

Tons of dung are trundled away. | 0:31:13 | 0:31:15 | |

The dung ball, with an egg inside, is buried. | 0:31:17 | 0:31:20 | |

A warm and delicious home, at least for a dung beetle larva. | 0:31:20 | 0:31:25 | |

Birds and mammals almost never turn their homes into traps, | 0:31:28 | 0:31:31 | |

as spiders do. | 0:31:31 | 0:31:34 | |

Human beings and burrowing owls are said to be the only examples. | 0:31:34 | 0:31:37 | |

A chick takes some dung down the burrow. | 0:31:41 | 0:31:44 | |

Maybe it's learning the connection with food. | 0:31:48 | 0:31:51 | |

It's a step in the right direction. | 0:31:51 | 0:31:53 | |

The owl mother doesn't agree and turns it into a lesson on housework. | 0:31:55 | 0:31:59 | |

Homes are hard work and there's a lot for young animals to learn. | 0:32:11 | 0:32:15 | |

Home making requires a sense of place, | 0:32:17 | 0:32:19 | |

as well as working out how to get along in a community. | 0:32:19 | 0:32:23 | |

The trap seems to have worked. | 0:32:25 | 0:32:27 | |

Food is always critical, | 0:32:44 | 0:32:46 | |

so many animal builders put a larder at the heart of their homes. | 0:32:46 | 0:32:51 | |

The beavers' system of canals and ponds is a massive cold store. | 0:32:55 | 0:32:59 | |

Beavers eat bark and leaves | 0:33:04 | 0:33:06 | |

and stocking the larder is a job that takes months. | 0:33:06 | 0:33:09 | |

The beavers wedge the branches down in the mud. | 0:33:11 | 0:33:15 | |

Even stored underwater, a potential burglar spots the stockpile. | 0:33:19 | 0:33:23 | |

But the moose is soon told that this store is private property. | 0:33:31 | 0:33:35 | |

A few tail-slaps and the intruder gets the message. | 0:33:40 | 0:33:44 | |

A house is of little use if there's no food. | 0:33:56 | 0:33:59 | |

Winter in Outer Mongolia would be hard for a hamster, | 0:33:59 | 0:34:04 | |

without a well-stocked store room. | 0:34:04 | 0:34:07 | |

Down the burrow, there are several rooms. | 0:34:11 | 0:34:15 | |

In the bedroom, the young are kept warm in straw | 0:34:15 | 0:34:19 | |

and fed by their mother. | 0:34:19 | 0:34:20 | |

Next door is the larder. | 0:34:25 | 0:34:29 | |

All autumn, they gathered seeds in their cheek pouches | 0:34:29 | 0:34:32 | |

and brought them down here. | 0:34:32 | 0:34:33 | |

Thanks to the seeds staying safe and dry, | 0:34:33 | 0:34:37 | |

the hamsters can start a family while it's still barren outside. | 0:34:37 | 0:34:41 | |

Our own earliest buildings may have been grain stores. | 0:34:44 | 0:34:48 | |

Protecting food for winter | 0:34:48 | 0:34:49 | |

enables house builders to move into colder areas | 0:34:49 | 0:34:52 | |

where the homeless could never survive. | 0:34:52 | 0:34:55 | |

Some homes go a stage further. | 0:35:01 | 0:35:03 | |

They have a living larder. | 0:35:03 | 0:35:06 | |

A mole's network of dark passages | 0:35:12 | 0:35:15 | |

can be extended at up to two metres an hour | 0:35:15 | 0:35:18 | |

and provide the mole's food. | 0:35:18 | 0:35:20 | |

Earthworms burrow through the walls by accident | 0:35:28 | 0:35:31 | |

and the star nosed mole has special worm-detecting feelers on its nose. | 0:35:31 | 0:35:37 | |

This housebound animal has a curious reputation | 0:35:40 | 0:35:43 | |

as the fastest eater on record. | 0:35:43 | 0:35:46 | |

An earthworm can disappear in a quarter of a second. | 0:35:46 | 0:35:51 | |

Not everyone can build a house where your food literally | 0:35:53 | 0:35:56 | |

drops in for dinner - and not everyone likes earthworms. | 0:35:56 | 0:36:01 | |

In China, bamboo is one of the fastest growing plants, | 0:36:04 | 0:36:09 | |

but I have heard of it occasionally growing back into the ground. | 0:36:09 | 0:36:13 | |

Under the bamboo is a quarter of a mile of tunnelling, | 0:36:30 | 0:36:35 | |

built over several years by bamboo rats. | 0:36:35 | 0:36:40 | |

The tunnels follow the roots | 0:36:53 | 0:36:55 | |

which run along the ceiling, like service pipes. | 0:36:55 | 0:36:59 | |

She checks the bamboo by smell. | 0:36:59 | 0:37:02 | |

If the roots put out a new shoot, she can sense the fresh growth | 0:37:02 | 0:37:06 | |

and when it's the right length, she harvests it. | 0:37:06 | 0:37:09 | |

The house has become a farm. | 0:37:11 | 0:37:13 | |

She has the same iron-coated teeth as the beavers. | 0:37:22 | 0:37:26 | |

Both are rodents, which are the vast majority of mammal house builders. | 0:37:26 | 0:37:31 | |

Her young have never been out. | 0:37:33 | 0:37:36 | |

She's blocked the exits. | 0:37:36 | 0:37:38 | |

The outside world might as well not exist. | 0:37:38 | 0:37:42 | |

The little ones seem determined to explore, | 0:37:47 | 0:37:50 | |

but may get lost in the network of tunnels. | 0:37:50 | 0:37:53 | |

So, she literally drags them | 0:37:53 | 0:37:56 | |

around the labyrinth of her underground bamboo farm. | 0:37:56 | 0:37:59 | |

American beavers build canals to carry trees | 0:38:10 | 0:38:14 | |

and Chinese bamboo rats harvest bamboo underground, | 0:38:14 | 0:38:18 | |

but in South America, | 0:38:18 | 0:38:20 | |

another animal takes the idea of a home farm a stage further. | 0:38:20 | 0:38:23 | |

Leaf and grass-cutter ants | 0:38:52 | 0:38:55 | |

take about 10% of the forest's growth underground, to fungus farms. | 0:38:55 | 0:39:01 | |

The white fungus grows on the chopped-up leaves | 0:39:02 | 0:39:05 | |

and is pretty much all the ants eat. | 0:39:05 | 0:39:09 | |

The fungus farm generates heat and carbon dioxide. | 0:39:09 | 0:39:13 | |

Pipes lead to a large mound above the ground. | 0:39:13 | 0:39:17 | |

The chimneys are like the raised prairie dog burrows, | 0:39:17 | 0:39:21 | |

drawing the air through the nest. | 0:39:21 | 0:39:23 | |

Nobody knew how big grass-cutter ant cities were, | 0:39:24 | 0:39:29 | |

so scientists poured a liquid cement into an old nest. | 0:39:29 | 0:39:34 | |

Once the concrete was set, | 0:39:37 | 0:39:39 | |

they dug away the earth to reveal an extraordinary secret city. | 0:39:39 | 0:39:43 | |

There are subterranean highways connecting the main chambers, | 0:39:49 | 0:39:54 | |

with side roads to fungus farms, huge rubbish pits | 0:39:54 | 0:39:58 | |

and temperature-controlled nurseries. | 0:39:58 | 0:40:01 | |

This is one house for 12 million inhabitants. | 0:40:08 | 0:40:12 | |

That's more than London or New York. | 0:40:13 | 0:40:15 | |

On our scale, it is a mile deep, and five miles across. | 0:40:18 | 0:40:22 | |

The social insects are nature's finest architects. | 0:40:31 | 0:40:36 | |

These three-metre-high termite mounds all point north to south. | 0:40:40 | 0:40:45 | |

In the morning and evening they face the sun and are warmed, | 0:40:50 | 0:40:54 | |

but at noon, they are sideways on and so don't overheat. | 0:40:54 | 0:40:58 | |

Our large buildings could follow this simple trick. | 0:41:00 | 0:41:04 | |

However, this is not the whole story. | 0:41:04 | 0:41:08 | |

Half the year this is a swamp and the sail-like shape and larger | 0:41:08 | 0:41:13 | |

surface areas are perfect for keeping the colony dry, as well as warm. | 0:41:13 | 0:41:18 | |

Most termites avoid overheating by descending into lower levels | 0:41:24 | 0:41:29 | |

during the hotter part of the day. | 0:41:29 | 0:41:30 | |

But these termites have found an architectural solution | 0:41:30 | 0:41:35 | |

to the problem. | 0:41:35 | 0:41:36 | |

Finding an egg 1,000 times your size in your house must be puzzling. | 0:41:45 | 0:41:50 | |

Terrifying, when it starts to hatch. | 0:41:50 | 0:41:53 | |

The gigantic aliens are lace monitor lizards. | 0:41:58 | 0:42:02 | |

Their exit is closed. The termites repaired the hole in the wall | 0:42:06 | 0:42:11 | |

the monitor mother made to lay her eggs. | 0:42:11 | 0:42:14 | |

They are trapped. | 0:42:14 | 0:42:16 | |

It seems almost incredible that their mother would return to release them. | 0:42:37 | 0:42:42 | |

These lizards could not have chosen a better nursery - | 0:42:46 | 0:42:50 | |

protected from predators | 0:42:50 | 0:42:52 | |

and incubated at the perfect temperature. | 0:42:52 | 0:42:55 | |

The termites must repair the mound. | 0:43:03 | 0:43:07 | |

They use mud and mortar out of their back end. | 0:43:07 | 0:43:10 | |

The walls are essential to stay within half a degree centigrade | 0:43:12 | 0:43:16 | |

of 30, whatever the weather outside. | 0:43:16 | 0:43:19 | |

Far from the tropics, insects have resorted to central heating. | 0:43:23 | 0:43:27 | |

In a hollow tree, a Japanese giant hornet | 0:43:28 | 0:43:32 | |

starts to build a city with cavity walls and electric radiators. | 0:43:32 | 0:43:37 | |

The queen first makes a few compartments. | 0:43:39 | 0:43:41 | |

An egg in each hatches into a larva. | 0:43:41 | 0:43:44 | |

It spins a silk cocoon for itself that has extraordinary properties. | 0:43:44 | 0:43:50 | |

The silk is like a thermostatic electric blanket. | 0:43:50 | 0:43:54 | |

It stores heat as electrical charge, | 0:43:54 | 0:43:57 | |

which automatically turns back into heat if the nest cools. | 0:43:57 | 0:44:02 | |

Her daughters pupate and emerge. | 0:44:04 | 0:44:09 | |

They are the first battalion of builders. | 0:44:09 | 0:44:11 | |

They add additional floors, suspended in the middle. | 0:44:11 | 0:44:15 | |

Supporting columns are moulded. | 0:44:15 | 0:44:19 | |

They build with chewed-up wood pulp, the same material as paper. | 0:44:19 | 0:44:23 | |

As more of the queen's larvae hatch, they start demanding food, | 0:44:28 | 0:44:32 | |

banging and scraping their heads on the walls. | 0:44:32 | 0:44:35 | |

The workers collect insects and mash them into a paste for the larvae. | 0:44:40 | 0:44:45 | |

The outside walls are extended downwards, with up to eight | 0:44:52 | 0:44:56 | |

layers of cavity insulation, and built-in flues and ducts. | 0:44:56 | 0:45:01 | |

Like the termites, a few simple instructions may come together | 0:45:01 | 0:45:05 | |

to build a surprisingly complex design. | 0:45:05 | 0:45:08 | |

Scientists call this an "emergent property". | 0:45:08 | 0:45:12 | |

And what emerges, after four months, | 0:45:12 | 0:45:15 | |

is a hornet's nest almost a metre tall. | 0:45:15 | 0:45:18 | |

If it's cold, the nest is heated by the larvae and their silk blankets, | 0:45:29 | 0:45:36 | |

but on hot days, cooling air is fanned in. | 0:45:36 | 0:45:38 | |

This nest is held within two degrees of 30. | 0:45:40 | 0:45:44 | |

The colony behaves as much like a warm-blooded animal as a house. | 0:45:44 | 0:45:49 | |

Towards autumn, the queen turns to producing new queens for next year. | 0:45:54 | 0:45:58 | |

She, and all her workers, will soon die here, | 0:46:01 | 0:46:03 | |

exhausted and now expendable. | 0:46:03 | 0:46:06 | |

The city will crumble, too, and can never be reused. | 0:46:07 | 0:46:11 | |

In the final days of her life, | 0:46:12 | 0:46:15 | |

the queen ensured that a few larvae were fed | 0:46:15 | 0:46:17 | |

and fresh queen hornets emerge. | 0:46:17 | 0:46:20 | |

Each faces a winter of hibernation and, in spring, starts building | 0:46:22 | 0:46:27 | |

a brand new edifice 40,000 times her size. | 0:46:27 | 0:46:31 | |

For every home, there comes a time to move on. | 0:46:33 | 0:46:38 | |

There is one animal in the rainforest | 0:46:51 | 0:46:54 | |

that builds the most extraordinary city of all. | 0:46:54 | 0:46:57 | |

Army ants kill almost everything they can | 0:46:59 | 0:47:02 | |

and carry it all back to their home. | 0:47:02 | 0:47:04 | |

Their house is a living building entirely made of ants, | 0:47:05 | 0:47:10 | |

called a bivouac. | 0:47:10 | 0:47:11 | |

The legs carry the weight of the whole nest. | 0:47:14 | 0:47:17 | |

Big cities have big problems. | 0:47:26 | 0:47:29 | |

The ants generate so much waste that they need a rubbish tip. | 0:47:29 | 0:47:33 | |

The carcasses of dead insects, and old cocoons are taken | 0:47:34 | 0:47:37 | |

out of the city to the dump. | 0:47:37 | 0:47:40 | |

Soon the colony sits in a sea of municipal waste | 0:47:41 | 0:47:44 | |

and all the surrounding food has gone. | 0:47:44 | 0:47:47 | |

So, they unhook themselves at night and set off. | 0:47:50 | 0:47:54 | |

Pupae and larvae are carried, and the queen is protected | 0:47:56 | 0:47:59 | |

behind a cavalcade of soldiers. | 0:47:59 | 0:48:02 | |

A new site is chosen and living ropes become columns. | 0:48:12 | 0:48:16 | |

They seem to build around a frame, | 0:48:17 | 0:48:19 | |

but since every site is different, the design is never identical. | 0:48:19 | 0:48:23 | |

The frame is filled in with walls, | 0:48:27 | 0:48:29 | |

to create corridors and rooms, all made of ants. | 0:48:29 | 0:48:33 | |

Their new neighbourhood will be stripped of prey in a few days. | 0:48:34 | 0:48:38 | |

If the ants couldn't move their city, | 0:48:40 | 0:48:44 | |

they'd quickly eat themselves into extinction. | 0:48:44 | 0:48:47 | |

All houses face the same dilemma. | 0:48:50 | 0:48:52 | |

The beavers have felled hundreds of tons of wood. | 0:48:54 | 0:48:57 | |

After four or five years, there is nothing left but bushes. | 0:48:57 | 0:49:01 | |

The ponds have silted up, and without logs for repair, | 0:49:02 | 0:49:05 | |

things start to fall apart. | 0:49:05 | 0:49:07 | |

The beavers make do for a while on shrubs, like willow herbs, | 0:49:16 | 0:49:21 | |

but even these, they eat faster than can grow back. | 0:49:21 | 0:49:24 | |

As their lake shrinks, they will abandon their home. | 0:49:27 | 0:49:31 | |

Almost all homes become unsustainable, eventually. | 0:49:35 | 0:49:39 | |

The rivers are littered with empty lodges and broken dams. | 0:49:40 | 0:49:45 | |

Every construction is an attempt to tame nature... | 0:49:48 | 0:49:51 | |

and nature will always win, in the end. | 0:49:51 | 0:49:55 | |

Things are even tougher for prairie dogs. | 0:49:57 | 0:49:59 | |

In summer, the land dries. | 0:50:01 | 0:50:04 | |

The cattle and buffalo can move, | 0:50:04 | 0:50:06 | |

but the dog towns can't and the families have nowhere else to go. | 0:50:06 | 0:50:11 | |

The owl family can all fly now. They can come and go. | 0:50:11 | 0:50:16 | |

The prairie dogs eat the remaining grass, | 0:50:19 | 0:50:21 | |

until their neighbourhood becomes a dust bowl. | 0:50:21 | 0:50:24 | |

They face starvation. | 0:50:30 | 0:50:32 | |

The young are a few months old | 0:50:35 | 0:50:38 | |

and now the colony turns against them. | 0:50:38 | 0:50:40 | |

Neighbours start to hunt down cubs. | 0:50:40 | 0:50:43 | |

Even cousins and aunts turn nasty. | 0:50:43 | 0:50:46 | |

In a dry year, up to half of the young are killed. | 0:50:48 | 0:50:52 | |

Stuck underground, out of sight, their home becomes a prison, a tomb. | 0:51:05 | 0:51:11 | |

THUNDER RUMBLES | 0:51:17 | 0:51:21 | |

Salvation does come in the end | 0:51:21 | 0:51:23 | |

for the few survivors inside their houses. | 0:51:23 | 0:51:26 | |

In autumn, the rains replenish the land | 0:51:38 | 0:51:42 | |

and, in spring, the grass grows back. | 0:51:42 | 0:51:46 | |

The prairie dogs have done no permanent damage. | 0:51:53 | 0:51:56 | |

They help the grassland over the years, | 0:51:58 | 0:52:00 | |

by mowing and fertilising their gardens. | 0:52:00 | 0:52:03 | |

The neighbourhood returns to normal. | 0:52:07 | 0:52:10 | |

The beavers have started a new life a couple of miles downstream. | 0:52:19 | 0:52:23 | |

They have found ponds built generations ago, | 0:52:25 | 0:52:28 | |

overgrown and abandoned. | 0:52:28 | 0:52:30 | |

They have repaired the dams and re-opened the canals. | 0:52:30 | 0:52:35 | |

The trees here have regenerated, | 0:52:36 | 0:52:38 | |

thanks to the fertile silt clogging the old ponds. | 0:52:38 | 0:52:42 | |

We can begin to see why not every animal makes a home. | 0:52:46 | 0:52:50 | |

You can't rely on one place for long. | 0:52:50 | 0:52:54 | |

For many, the risks are too great. | 0:52:54 | 0:52:57 | |

The restless and the hungry follow the seasons in great migrations. | 0:53:02 | 0:53:07 | |

The world is constantly changing | 0:53:14 | 0:53:18 | |

and even the wisest animals struggle to keep up. | 0:53:18 | 0:53:22 | |

These are the homeless of the Earth | 0:53:36 | 0:53:40 | |

and, until recently, we were among them. | 0:53:40 | 0:53:43 | |

So how did we become the greatest homemaker of all? | 0:53:46 | 0:53:51 | |

Our closest animal relatives are still homeless, | 0:53:54 | 0:53:57 | |

unable even to keep out of the rain. | 0:53:57 | 0:54:00 | |

Apes and monkeys don't make shelters, | 0:54:01 | 0:54:03 | |

though a gorilla's hands and brain are easily up to the job. | 0:54:03 | 0:54:07 | |

The priority for these mountain gorillas is to find fresh food, | 0:54:11 | 0:54:15 | |

so they keep moving. A house would only tie them down. | 0:54:15 | 0:54:19 | |

The signs of an ability, however, are here. | 0:54:23 | 0:54:26 | |

An improvised roof is better than none, while it lasts. | 0:54:27 | 0:54:30 | |

Our ape cousins build beds, or even platforms, woven from branches. | 0:54:36 | 0:54:40 | |

But they never sit under them, like a roof. | 0:54:40 | 0:54:42 | |

We may have started with twisting branches into shelters, | 0:54:46 | 0:54:50 | |

but there is another way to get out of the rain. | 0:54:50 | 0:54:52 | |

In Kenya, on Mount Suswa, baboons use caves at night. | 0:54:54 | 0:54:59 | |

Caves like these contain the earliest evidence of human habitation. | 0:55:01 | 0:55:07 | |

The monkeys' fingers and sense of balance | 0:55:16 | 0:55:19 | |

take them along ledges impossible for leopards and hyenas to follow. | 0:55:19 | 0:55:22 | |

Many of our phobias may have originated here, | 0:55:26 | 0:55:30 | |

with bats and snakes, | 0:55:30 | 0:55:32 | |

and strange, ghostly noises in the dark. | 0:55:32 | 0:55:35 | |

We probably became serious builders | 0:55:52 | 0:55:55 | |

only a few hundred thousand years ago, at the most. | 0:55:55 | 0:55:58 | |

It is extraordinary what we have achieved. | 0:55:58 | 0:56:01 | |

We don't often realise how fragile all this is. | 0:56:09 | 0:56:12 | |

Our cities have all the problems of animal cities - | 0:56:17 | 0:56:20 | |

burglars and squatters, and getting the food in and the rubbish out. | 0:56:20 | 0:56:25 | |

To feed the city, we eat up the wilderness. | 0:56:26 | 0:56:30 | |

We forget that we kick animals out of their homes to do so. | 0:56:30 | 0:56:34 | |

Maybe we can be reminded by the refugees, | 0:56:37 | 0:56:42 | |

by an urban generation of peregrines and pigeons, | 0:56:42 | 0:56:45 | |

gulls and bats and foxes. | 0:56:45 | 0:56:47 | |

Animals will share our world, if we let them. | 0:56:52 | 0:56:55 | |

We can make space and help with protection, food and warmth. | 0:57:02 | 0:57:08 | |

We are homemakers, we understand. | 0:57:08 | 0:57:11 | |

We can build a world, surely, where animals can have a home, too. | 0:57:12 | 0:57:18 | |

# I'm coming home, I'm coming home | 0:57:21 | 0:57:26 | |

# Tell the world I'm coming home | 0:57:26 | 0:57:28 | |

# Let the rain wash away | 0:57:28 | 0:57:33 | |

# All the pain of yesterday | 0:57:33 | 0:57:36 | |

# I know my kingdom awaits | 0:57:36 | 0:57:41 | |

# And they've forgiven my mistakes | 0:57:41 | 0:57:44 | |

# I'm coming home, I'm coming home | 0:57:44 | 0:57:48 | |

# Tell the world I'm coming. # | 0:57:48 | 0:57:51 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:58:12 | 0:58:15 | |

E-mail [email protected] | 0:58:15 | 0:58:18 |