Future Fantastic Dara O Briain's Science Club

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Future Fantastic. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

Hello, I'm Dara O Briain. Welcome to the show which seeks out | 0:00:02 | 0:00:04 | |

the very latest ground-breaking ideas in science | 0:00:04 | 0:00:07 | |

and attempts to answer some of the most fundamental | 0:00:07 | 0:00:10 | |

questions in the cosmos. | 0:00:10 | 0:00:12 | |

Tonight, we're travelling into the future and seeing | 0:00:13 | 0:00:17 | |

what exactly it holds for us in the next five, ten or 50 years time. | 0:00:17 | 0:00:21 | |

This is the place where we find out how great ideas | 0:00:22 | 0:00:25 | |

are changing the world we live in. | 0:00:25 | 0:00:27 | |

Welcome to Science Club. | 0:00:28 | 0:00:29 | |

Yes, good evening. Welcome to the show, | 0:00:37 | 0:00:40 | |

and a great show tonight - some very eminent guests, later on. | 0:00:40 | 0:00:43 | |

We'll be joined by most of the usual suspects, | 0:00:43 | 0:00:45 | |

including resident experimentalist Professor Mark Miodownik. | 0:00:45 | 0:00:48 | |

Mark, what have you got for us tonight? | 0:00:48 | 0:00:50 | |

I'm showcasing some of the technologies of the future, | 0:00:50 | 0:00:53 | |

and, hopefully, not breaking them. | 0:00:53 | 0:00:54 | |

Because we have broken them repeatedly during the rehearsals. | 0:00:54 | 0:00:57 | |

On the show tonight, we are looking at the future. | 0:00:57 | 0:00:59 | |

Of course, to some extent, we're always looking at the future | 0:00:59 | 0:01:02 | |

on this show - but just how will our lives change over the next few years and decades? | 0:01:02 | 0:01:05 | |

What are we going to be using in our houses? | 0:01:05 | 0:01:07 | |

What are we going to be eating or wearing? | 0:01:07 | 0:01:10 | |

Our special guest - physicist and futurologist Professor Michio Kaku - | 0:01:10 | 0:01:13 | |

will be helping us with that later. Also on the show... | 0:01:13 | 0:01:15 | |

Alok investigates the most revolutionary brain imaging | 0:01:17 | 0:01:20 | |

techniques that promise to unlock the mysteries of our minds. | 0:01:20 | 0:01:23 | |

Do you think this is the beginnings | 0:01:23 | 0:01:25 | |

of a consciousness-detecting machine? | 0:01:25 | 0:01:27 | |

In the studio, we delve into cryonics - | 0:01:30 | 0:01:32 | |

freezing ourselves after death. | 0:01:32 | 0:01:34 | |

Imagine that is your cell... | 0:01:34 | 0:01:36 | |

'And discover a link to ice cream.' | 0:01:37 | 0:01:39 | |

Microscopically smooth! | 0:01:39 | 0:01:40 | |

And we come face to face with a robot that can finally ape | 0:01:42 | 0:01:45 | |

that most human of skills - touch. | 0:01:45 | 0:01:48 | |

ROBOT: Squishy, compressible and soft. | 0:01:48 | 0:01:50 | |

First to cities. Over the last couple of thousand years, | 0:01:53 | 0:01:56 | |

we humans seem to have decided that living together in cities was | 0:01:56 | 0:01:59 | |

the best way to organise ourselves. | 0:01:59 | 0:02:01 | |

Over half of us worldwide now live this way. | 0:02:01 | 0:02:04 | |

We've become an urban species. | 0:02:04 | 0:02:06 | |

So, how will we run our super cities as they get bigger and bigger? | 0:02:06 | 0:02:10 | |

Dr Helen Czerski has been to Brazil to investigate. | 0:02:10 | 0:02:13 | |

Rio de Janeiro - home to 6.3 million people. | 0:02:17 | 0:02:22 | |

That number will explode when the city hosts both the World Cup | 0:02:23 | 0:02:27 | |

and the Olympics in the next three years. | 0:02:27 | 0:02:29 | |

Its infrastructure will be pushed to breaking point, | 0:02:31 | 0:02:35 | |

so, here, they're already tackling challenges that we're all | 0:02:35 | 0:02:40 | |

going to face, as our cities grow faster than ever. | 0:02:40 | 0:02:43 | |

This is Rio's Command Operations Centre. | 0:02:45 | 0:02:49 | |

An extraordinary control room for the city. | 0:02:54 | 0:02:57 | |

You'd think that things like this might be hidden away | 0:03:00 | 0:03:02 | |

in lots of cities, but, actually, | 0:03:02 | 0:03:04 | |

nothing quite like this exists anywhere else in the world. | 0:03:04 | 0:03:08 | |

Essentially, what they've done is give the city a brain. | 0:03:10 | 0:03:13 | |

Any time, anywhere, if something happens in central Rio, | 0:03:15 | 0:03:19 | |

they'll know about it here. | 0:03:19 | 0:03:20 | |

This mission control is radically changing the way the city can | 0:03:22 | 0:03:26 | |

respond to any incident, however big or small. | 0:03:26 | 0:03:31 | |

-So, this is an incident going on in the city now. -Yes, a bus broke down. | 0:03:31 | 0:03:34 | |

-The red circle is where the bus...? -The red circle is the problem, | 0:03:34 | 0:03:37 | |

and the bigger red circle is the impact area. | 0:03:37 | 0:03:40 | |

Today, it's just a broken-down bus, | 0:03:42 | 0:03:44 | |

but it shows how comprehensive the system is. | 0:03:44 | 0:03:46 | |

The overlaid satellite image immediately shows exactly what might | 0:03:48 | 0:03:51 | |

be affected within the impact area, like schools or businesses. | 0:03:51 | 0:03:55 | |

But, crucially, it has live information about what resources | 0:03:57 | 0:04:00 | |

are available nearby, as every one of them is tracked through GPS. | 0:04:00 | 0:04:05 | |

We have two tow trucks near that place, and we have guards there too. | 0:04:05 | 0:04:11 | |

We call the tow trucks, we call the guards, | 0:04:11 | 0:04:14 | |

and our crew here, they work together to solve this | 0:04:14 | 0:04:17 | |

as fast as possible. | 0:04:17 | 0:04:18 | |

-And you can see details about who the guard is. -We have his name. | 0:04:21 | 0:04:26 | |

He works from 7am till 7pm. | 0:04:26 | 0:04:28 | |

LAUGHING: Do you know everything about him? | 0:04:28 | 0:04:30 | |

We know his battery level, for example. | 0:04:30 | 0:04:34 | |

SPEAKS PORTUGUESE | 0:04:34 | 0:04:36 | |

-75%. -So, you can tell that he's probably OK to talk to, | 0:04:37 | 0:04:41 | |

cos his battery isn't about to die. | 0:04:41 | 0:04:43 | |

We have his cellphone, we can call him. | 0:04:43 | 0:04:45 | |

But the system isn't just about responding to what's happening today. | 0:04:45 | 0:04:49 | |

They're also collecting data and analysing it. | 0:04:49 | 0:04:52 | |

They're learning how their city works. | 0:04:52 | 0:04:55 | |

We have discovered, for example, that every Friday, at 5.30pm, | 0:04:55 | 0:04:59 | |

we have most of the motorcycle accidents. | 0:04:59 | 0:05:03 | |

So, you can see patterns... | 0:05:03 | 0:05:06 | |

Like, you always have a motorcycle accident at 5.30 on a Friday, | 0:05:06 | 0:05:10 | |

and start to try and work out why that is, and maybe prevent it. | 0:05:10 | 0:05:13 | |

Prevent it, put a campaign, work with the information that we have. | 0:05:13 | 0:05:17 | |

It's that ability to learn that gives this system so much potential. | 0:05:18 | 0:05:22 | |

Rio can monitor itself to such a remarkable degree, | 0:05:24 | 0:05:28 | |

and it can adapt and predict. | 0:05:28 | 0:05:30 | |

It has the potential, more than any other city, | 0:05:31 | 0:05:34 | |

to respond to change, | 0:05:34 | 0:05:36 | |

and, as more and more of us choose to live in cities the world over, | 0:05:36 | 0:05:41 | |

and they became ever more complex, I think this has universal application. | 0:05:41 | 0:05:46 | |

APPLAUSE | 0:05:47 | 0:05:50 | |

-It's essentially treating a city like a giant organism. -Yeah. | 0:05:51 | 0:05:54 | |

And this is the brain, the central nervous system. | 0:05:54 | 0:05:56 | |

And we're these little ants who inhabit it. I mean, I like it. | 0:05:56 | 0:06:01 | |

-It's really impressive. -It is. | 0:06:01 | 0:06:03 | |

We're asking about cities, the future and how we live. | 0:06:03 | 0:06:06 | |

What we build with seems like... | 0:06:06 | 0:06:07 | |

Well, we've been building with the same stuff for a long time now, | 0:06:07 | 0:06:10 | |

in our cities. Concrete, for example. | 0:06:10 | 0:06:12 | |

Yeah, but the concrete of the future may be very different. | 0:06:12 | 0:06:14 | |

I want to show you a very special new type of concrete. | 0:06:14 | 0:06:17 | |

AUDIENCE: Ooh! MARK: Yeah! | 0:06:17 | 0:06:19 | |

DARA LAUGHS | 0:06:19 | 0:06:21 | |

How great is that? It doesn't even need to be that close to it. | 0:06:21 | 0:06:23 | |

-No, and look. If I sort of walk past... -How mad is that? | 0:06:23 | 0:06:28 | |

And it's not like there's glass fibres in it or woven through it... | 0:06:28 | 0:06:31 | |

There's optical fibres. These are the things that carry our telephone | 0:06:31 | 0:06:34 | |

conversations at the moment, these optical fibres, | 0:06:34 | 0:06:37 | |

and they're threaded through this material, | 0:06:37 | 0:06:39 | |

so they're conveying, instead of information, | 0:06:39 | 0:06:41 | |

our telephone conversations, light from one side of the building | 0:06:41 | 0:06:44 | |

to the other. You can imagine the cities of the future, | 0:06:44 | 0:06:46 | |

where we haven't just got glass walls or opaque walls, | 0:06:46 | 0:06:49 | |

we've got all these variations in between. | 0:06:49 | 0:06:51 | |

I think it would be great to have a bathroom wall of this stuff, | 0:06:51 | 0:06:54 | |

because every... LAUGHTER | 0:06:54 | 0:06:56 | |

No, Imagine! Every shower you take will be a bit like | 0:06:56 | 0:06:58 | |

the opening of a Bond film. | 0:06:58 | 0:07:00 | |

-You'll be like this, and it'll just make it more fun. -Sexy all the time. | 0:07:00 | 0:07:04 | |

-Constantly. -Cos no-one can really see what you actually look like. | 0:07:04 | 0:07:08 | |

No, of course not, but people of the future will be constantly sexy. | 0:07:08 | 0:07:11 | |

Thank you, Mark Miodownik. | 0:07:11 | 0:07:12 | |

APPLAUSE | 0:07:12 | 0:07:14 | |

I believe it was Whitney Houston who once said that children are | 0:07:15 | 0:07:18 | |

our future, but some children step further into the future than others. | 0:07:18 | 0:07:22 | |

Take Taylor Wilson, for example, who, at the age of 14, | 0:07:22 | 0:07:25 | |

built a nuclear fusion reactor in his garage. | 0:07:25 | 0:07:29 | |

Or Jack Andraka, who invented a diagnostic tool to detect | 0:07:29 | 0:07:32 | |

pancreatic cancer when he was 15. | 0:07:32 | 0:07:36 | |

Our special guest tonight was one of those children. | 0:07:36 | 0:07:38 | |

In fact, he built a particle accelerator in his garage | 0:07:38 | 0:07:40 | |

when he was 17 years old. | 0:07:40 | 0:07:42 | |

Now, he's Professor of Physics at City University of New York, | 0:07:42 | 0:07:45 | |

and, of course, an expert in all things futuristic. | 0:07:45 | 0:07:48 | |

-Michio Kaku, pleasure to have you here. -Glad to be on the show. | 0:07:48 | 0:07:50 | |

Good stuff. | 0:07:50 | 0:07:52 | |

Tell me about this...particle accelerator in your garage. | 0:07:52 | 0:07:56 | |

That's right. I was 17. | 0:07:56 | 0:07:58 | |

I assembled 400 pounds of transformer steel, 22 miles of copper wire, | 0:07:58 | 0:08:02 | |

and, in my mum's garage, I assembled a six kilowatt atom smasher. | 0:08:02 | 0:08:07 | |

Every time I turned it on, | 0:08:07 | 0:08:08 | |

I blew out every single circuit breaker in the house. | 0:08:08 | 0:08:11 | |

My mum would wonder, "Why can't my son play baseball?" | 0:08:11 | 0:08:14 | |

LAUGHTER | 0:08:14 | 0:08:16 | |

-What were you looking to create with this? -I wanted to create antimatter. | 0:08:16 | 0:08:20 | |

-In your garage? -That's right. LAUGHTER | 0:08:20 | 0:08:23 | |

With a particle accelerator, whizzing around like that. | 0:08:23 | 0:08:26 | |

And we do it now, outside Geneva, Switzerland. | 0:08:26 | 0:08:29 | |

It's called the Large Hadron Collider. | 0:08:29 | 0:08:30 | |

It's a very big version of what I built when I was 17 years of age. | 0:08:30 | 0:08:34 | |

-Did you find an antimatter with this? -Unfortunately not. | 0:08:34 | 0:08:36 | |

-I didn't look hard enough. -But this is what got you... | 0:08:36 | 0:08:39 | |

You took it to a science fair, which I presume you won. | 0:08:39 | 0:08:41 | |

I can't imagine anyone's project on volcanoes beating that. | 0:08:41 | 0:08:46 | |

Then it got you into Harvard, and from then, and from then... | 0:08:46 | 0:08:49 | |

That's right. I was a kid coming from a very poor background, | 0:08:49 | 0:08:52 | |

but I had big dreams. However, the meal ticket was a scholarship to | 0:08:52 | 0:08:56 | |

Harvard University, cos that's what set me off in the direction | 0:08:56 | 0:08:59 | |

of working in theoretical physics and working on string theory, | 0:08:59 | 0:09:02 | |

which is what I do for a living. That's my day job. | 0:09:02 | 0:09:05 | |

You are an expert on the future, as well. | 0:09:05 | 0:09:07 | |

Tell me what we can expect to change. | 0:09:07 | 0:09:10 | |

Well, within ten years, computer chips will cost about a penny, | 0:09:10 | 0:09:13 | |

so the internet will be everywhere and nowhere, | 0:09:13 | 0:09:15 | |

including your contact lens. | 0:09:15 | 0:09:17 | |

I will see you with my contact lens, I will see your biography. | 0:09:17 | 0:09:21 | |

If you speak to me in Chinese, I will see subtitles beneath you. | 0:09:21 | 0:09:25 | |

And who are the first people to buy internet contact lenses? | 0:09:25 | 0:09:28 | |

College students studying for final examinations. | 0:09:28 | 0:09:31 | |

LAUGHTER | 0:09:31 | 0:09:33 | |

Even wallpaper is going to be intelligent. | 0:09:33 | 0:09:36 | |

You simply go to the wall, say, "Mirror, mirror, on the wall", | 0:09:36 | 0:09:38 | |

and then Robo Doc appears - | 0:09:38 | 0:09:40 | |

an animated, artificially intelligent doctor | 0:09:40 | 0:09:43 | |

answering any medical questions. | 0:09:43 | 0:09:45 | |

And, if you want a few laughs, Robo Stand Up Comic will appear right | 0:09:45 | 0:09:49 | |

in your wallpaper, almost for free, because of artificial intelligence. | 0:09:49 | 0:09:52 | |

No, we don't work for free. | 0:09:52 | 0:09:54 | |

LAUGHTER | 0:09:54 | 0:09:56 | |

I don't know where you're getting that from. | 0:09:56 | 0:09:58 | |

Will we all be living on Earth? Do you see that? | 0:09:58 | 0:10:00 | |

Are we going to overcome the difficulties of interplanetary | 0:10:00 | 0:10:04 | |

transport? The radiation, the time taken? | 0:10:04 | 0:10:08 | |

I think, in the long term, as Stephen Hawking has also emphasised, | 0:10:08 | 0:10:12 | |

my colleague, we should become a two-planet species, | 0:10:12 | 0:10:15 | |

because look at the dinosaurs. | 0:10:15 | 0:10:17 | |

The dinosaurs didn't have a space programme. | 0:10:17 | 0:10:20 | |

And look what happened to them. LAUGHTER | 0:10:20 | 0:10:23 | |

Is this basically, long term, | 0:10:23 | 0:10:24 | |

we're going to get wiped out by a comet or an asteroid at some stage? | 0:10:24 | 0:10:27 | |

The earth is in the middle of a cosmic shooting gallery. | 0:10:27 | 0:10:29 | |

Look at Chelyabinsk, Russia. | 0:10:29 | 0:10:31 | |

That city was hit with an asteroid that blew up overhead. | 0:10:31 | 0:10:34 | |

If that had stayed intact for a few more seconds, it would | 0:10:34 | 0:10:38 | |

have hit the earth with the force of about 20 Hiroshima bombs. | 0:10:38 | 0:10:42 | |

And it just missed the earth by seconds. | 0:10:42 | 0:10:45 | |

That's how close we came to a disaster just a few months ago. | 0:10:45 | 0:10:48 | |

Do you see this as being a brighter future that we have ahead of us? | 0:10:48 | 0:10:52 | |

I think it's going to be a brighter future, | 0:10:52 | 0:10:54 | |

because science is the engine of prosperity. | 0:10:54 | 0:10:57 | |

All the wealth we see around us is due to science, | 0:10:57 | 0:11:00 | |

and science is going to continue to generate jobs, new industries, | 0:11:00 | 0:11:04 | |

make life easier, extend the human life span, | 0:11:04 | 0:11:07 | |

but there's always a price, and the price is privacy. | 0:11:07 | 0:11:10 | |

We'll probably have less privacy in the future, but we'll have | 0:11:10 | 0:11:14 | |

more abundance of wealth and we'll have a more convenient life. | 0:11:14 | 0:11:18 | |

OK, now, we have many questions to get through. | 0:11:18 | 0:11:20 | |

We're going to keep you here, but, for the time being, | 0:11:20 | 0:11:23 | |

-thank you very much, Dr Michio Kaku. We'll be talking to you later. -APPLAUSE | 0:11:23 | 0:11:26 | |

What are we going to look like as the future comes? | 0:11:32 | 0:11:35 | |

This is a genuine proposal that, if we conquer other planets, | 0:11:35 | 0:11:39 | |

because we're further away from the sun, we'll have to evolve | 0:11:39 | 0:11:41 | |

larger eyes to look like a meerkat or some sort of freaky creature. | 0:11:41 | 0:11:46 | |

One thing's for sure, however, | 0:11:46 | 0:11:47 | |

our brains will continue to mark us out as different from other animals, | 0:11:47 | 0:11:50 | |

and knowing more about how they work will be crucial. | 0:11:50 | 0:11:53 | |

Alok has been to the US to see the latest incredible leap forward | 0:11:53 | 0:11:56 | |

in our understanding of that most complex of structures. | 0:11:56 | 0:12:00 | |

When it comes to the brain, | 0:12:04 | 0:12:05 | |

it's fair to say we have almost no idea how it works. | 0:12:05 | 0:12:09 | |

We've been studying our brains for hundreds of years, but we still | 0:12:09 | 0:12:13 | |

don't know what a thought is, we don't really know what | 0:12:13 | 0:12:16 | |

memories are, never mind autism or schizophrenia. | 0:12:16 | 0:12:19 | |

That's because we don't understand enough about the anatomy | 0:12:19 | 0:12:21 | |

of our brains - how our brain cells communicate | 0:12:21 | 0:12:24 | |

and connect with each other, but that might be about to change. | 0:12:24 | 0:12:28 | |

I've come to Washington DC to meet | 0:12:30 | 0:12:32 | |

one of the world's most talented neuroscientists. | 0:12:32 | 0:12:35 | |

Karl Deisseroth and his team have just unveiled an incredible | 0:12:37 | 0:12:40 | |

new technology to reveal the wiring of the brain. | 0:12:40 | 0:12:43 | |

So, what I'm showing you here is an intact mouse brain. | 0:12:46 | 0:12:50 | |

We can see the structure from top to bottom, side to side, | 0:12:52 | 0:12:57 | |

without taking it apart. | 0:12:57 | 0:12:58 | |

This is incredible, it's like a Hollywood movie. | 0:13:00 | 0:13:03 | |

These dots, they're individual brain cells. | 0:13:03 | 0:13:05 | |

Those are individual brain cells. | 0:13:05 | 0:13:08 | |

And the lines between them are the connections between them. | 0:13:08 | 0:13:10 | |

Those are the wires, | 0:13:10 | 0:13:11 | |

those are the connections that send information back and forth. | 0:13:11 | 0:13:15 | |

His revolutionary technique reveals every brain cell, | 0:13:17 | 0:13:21 | |

every connection, in detail we never thought possible. | 0:13:21 | 0:13:24 | |

Deisseroth's technique will transform our understanding | 0:13:28 | 0:13:31 | |

of detailed brain structure. | 0:13:31 | 0:13:33 | |

To see inside a living brain at this level is years away. | 0:13:34 | 0:13:38 | |

But, in Boston, they have a scanner that's taking those first steps. | 0:13:38 | 0:13:43 | |

It's still experimental, | 0:13:43 | 0:13:45 | |

so I'm only slightly worried about going in there. | 0:13:45 | 0:13:48 | |

'Because I volunteered to have my brain scanned by it.' | 0:13:48 | 0:13:52 | |

-Hello, I'm Alok. -Great to meet you. -Lovely to meet you. | 0:13:52 | 0:13:54 | |

'It's been developed by Dr Van Wedeen, | 0:13:54 | 0:13:57 | |

'who's going to map my brain's wiring.' | 0:13:57 | 0:14:00 | |

OK, are we ready to go? | 0:14:00 | 0:14:02 | |

This scanner has the ability to detect neurons. | 0:14:02 | 0:14:06 | |

But, rather than the usual clumps of millions, | 0:14:06 | 0:14:09 | |

it can pick up bunches of around a thousand at a time. | 0:14:09 | 0:14:13 | |

It creates so much data that I won't be able to see | 0:14:14 | 0:14:17 | |

my wiring map for weeks. | 0:14:17 | 0:14:19 | |

Instead, I get a sneak preview of other people's brains. | 0:14:21 | 0:14:25 | |

-Here's what the diffusion image looks like. -Oh, wow. | 0:14:25 | 0:14:27 | |

It's just fibres everywhere. | 0:14:27 | 0:14:29 | |

These are the highest-resolution images of living neurons | 0:14:32 | 0:14:35 | |

we've ever had. | 0:14:35 | 0:14:37 | |

Each single coloured line represents thousands of brain cells, bundled in | 0:14:38 | 0:14:43 | |

pathways that connect the different regions of the brain to each other. | 0:14:43 | 0:14:47 | |

So, tell me, why is it important that we need a living wiring map of the brain? | 0:14:47 | 0:14:53 | |

Well, when you can look at living subjects, you can see changes over time. | 0:14:53 | 0:14:57 | |

You can see how the brain adapts following an injury or | 0:14:57 | 0:15:01 | |

increases in size following a learning process. | 0:15:01 | 0:15:03 | |

Learning a foreign language or learning a new skill. | 0:15:03 | 0:15:06 | |

It's a really unique window on how the brain works | 0:15:06 | 0:15:09 | |

in humans in general and also in you as an individual. | 0:15:09 | 0:15:13 | |

Dr Wedeen is also hopeful that it will lead us | 0:15:16 | 0:15:19 | |

to answer some of the most profound questions of all. | 0:15:19 | 0:15:22 | |

We've never trapped consciousness in a bottle. | 0:15:24 | 0:15:26 | |

There are many ideas for what it looks like. What its scale is. | 0:15:26 | 0:15:29 | |

Is it in one place or everywhere? Is it fast or slow or both? | 0:15:29 | 0:15:34 | |

That's the kind of question that we may see the answer to | 0:15:34 | 0:15:37 | |

-in a decade or so. -Are we seeing the beginnings | 0:15:37 | 0:15:40 | |

-of a consciousness-detecting machine here? -Yes, I think so. | 0:15:40 | 0:15:43 | |

I think there is a growing excitement | 0:15:43 | 0:15:45 | |

that the pieces of the puzzle are starting to appear. | 0:15:45 | 0:15:48 | |

With these two amazing new technologies, | 0:15:49 | 0:15:52 | |

we are seeing brain structure with unprecedented clarity. | 0:15:52 | 0:15:56 | |

We've never had such detailed wiring maps of the brain before. | 0:15:57 | 0:16:00 | |

They're going to revolutionise neuroscience and give us | 0:16:00 | 0:16:03 | |

our best chance yet at trying to understand things like | 0:16:03 | 0:16:06 | |

mental health, personality and even consciousness. | 0:16:06 | 0:16:10 | |

APPLAUSE | 0:16:10 | 0:16:13 | |

We have with us | 0:16:17 | 0:16:19 | |

in the studio Dr Molly Crockett from University College London | 0:16:19 | 0:16:22 | |

who's a cognitive neuroscientist. What do you make of this, Molly? | 0:16:22 | 0:16:25 | |

I think what's exciting about these techniques is that they really | 0:16:25 | 0:16:28 | |

complement what fMRI allows us to do, which is | 0:16:28 | 0:16:30 | |

to observe the brain as it's functioning in real-time. | 0:16:30 | 0:16:33 | |

How the brain is responding to decisions that people are making, | 0:16:33 | 0:16:37 | |

to stimuli, pictures, words, whatever you throw at people. | 0:16:37 | 0:16:41 | |

Would a parallel be we know the G's the A's, | 0:16:41 | 0:16:43 | |

the T's and the C's of the genome. | 0:16:43 | 0:16:47 | |

But we have to zoom out from that a bit to see how the genes | 0:16:47 | 0:16:50 | |

-interact and what they do? -Exactly. | 0:16:50 | 0:16:51 | |

Or another analogy would be like a computer program. | 0:16:51 | 0:16:54 | |

So at the top level an email program and you want to send | 0:16:54 | 0:16:57 | |

a message and that's sort of what the program is for. | 0:16:57 | 0:17:00 | |

Then one level down you have the algorithms, | 0:17:00 | 0:17:02 | |

the software that helps that message get sent. | 0:17:02 | 0:17:05 | |

And then at the lowest level you have the hardware, the transistors, | 0:17:05 | 0:17:09 | |

the silicon chips. | 0:17:09 | 0:17:10 | |

And what these techniques like CLARITY are doing | 0:17:10 | 0:17:13 | |

is letting us see the transistors. | 0:17:13 | 0:17:15 | |

But it's important also to keep in mind that we have to have | 0:17:15 | 0:17:18 | |

all the levels going at the same time, that psychology | 0:17:18 | 0:17:21 | |

and cognitive science are also really important in this endeavour. | 0:17:21 | 0:17:24 | |

It's worth saying also these techniques are going to get better | 0:17:24 | 0:17:27 | |

and what we need more of is actually reference brains | 0:17:27 | 0:17:29 | |

and then you can compare when someone gets ill or someone | 0:17:29 | 0:17:32 | |

has a particular condition or someone's learned something. | 0:17:32 | 0:17:34 | |

And you can start to do that fine-grained analysis. | 0:17:34 | 0:17:37 | |

That's what I think is quite interesting | 0:17:37 | 0:17:38 | |

when you get to things like learning, memory. | 0:17:38 | 0:17:41 | |

You can actually see these structural things in the brain. | 0:17:41 | 0:17:43 | |

We said you're part of a very select group. | 0:17:43 | 0:17:45 | |

You may be one of the reference brains yourself. | 0:17:45 | 0:17:47 | |

There's fewer than 50 people have had it done and you haven't seen it yet. | 0:17:47 | 0:17:51 | |

I haven't seen it yet. | 0:17:51 | 0:17:52 | |

I would love for my brain to be a reference brain for anything. | 0:17:52 | 0:17:55 | |

That would be hilarious. | 0:17:55 | 0:17:57 | |

-It would be so wrong. -It might well be. This is Alok's brain. | 0:17:57 | 0:18:00 | |

This is a Connectum of Alok's brain. You've got quite a curly brain. | 0:18:00 | 0:18:04 | |

What is striking is how little brain you have on one side of your head. | 0:18:06 | 0:18:10 | |

That's the left-hand side of my brain. | 0:18:10 | 0:18:12 | |

That means my logical side is very deficient, | 0:18:12 | 0:18:14 | |

whereas my creative side is through the roof. | 0:18:14 | 0:18:17 | |

I don't know why you're doing a science programme, | 0:18:17 | 0:18:20 | |

-you belong in the arts. -Why did I do a physics degree? I had no idea. | 0:18:20 | 0:18:24 | |

-We think there's stuff there. -It's probably true. | 0:18:24 | 0:18:27 | |

But they may have just put the resources into that. | 0:18:27 | 0:18:29 | |

Have you ever felt that absence on one side of your head? | 0:18:29 | 0:18:32 | |

I feel the emptiness most days. | 0:18:32 | 0:18:35 | |

There is a condition where you're born with only half a brain | 0:18:35 | 0:18:38 | |

-and actually you can develop quite normally. -What! | 0:18:38 | 0:18:41 | |

-It's amazing. -How amazing to have found that out on this show. | 0:18:41 | 0:18:44 | |

You were born with half a brain. | 0:18:44 | 0:18:46 | |

I feel like I should have had some counselling. | 0:18:46 | 0:18:49 | |

We're going to go another level up again | 0:18:49 | 0:18:51 | |

which is some of the work you do | 0:18:51 | 0:18:53 | |

would be the addition of hormones and chemicals into the brain. | 0:18:53 | 0:18:56 | |

-I know you do work with serotonin, for example. -Yes. | 0:18:56 | 0:18:59 | |

Serotonin is one of many chemicals in the brain that helps transmit | 0:18:59 | 0:19:03 | |

certain signals and we've done some work looking at how manipulating | 0:19:03 | 0:19:07 | |

serotonin levels and serotonin function in healthy volunteers | 0:19:07 | 0:19:10 | |

influences peoples' decision making. | 0:19:10 | 0:19:13 | |

So serotonin, does it mean you make better decisions | 0:19:13 | 0:19:16 | |

or more generous decisions or less spiteful? | 0:19:16 | 0:19:20 | |

You're more spiteful when your serotonin is low. | 0:19:20 | 0:19:22 | |

It's a complicated system. | 0:19:22 | 0:19:23 | |

So we don't have a really good grip on this but we do know that | 0:19:23 | 0:19:27 | |

if you're chronically stressed, this will, over time, | 0:19:27 | 0:19:31 | |

tend to deplete your serotonin levels. | 0:19:31 | 0:19:36 | |

Which could shift you towards a more spiteful or retaliatory strategy | 0:19:36 | 0:19:41 | |

over time. | 0:19:41 | 0:19:42 | |

That work has been done in primates so we don't know for sure | 0:19:42 | 0:19:45 | |

if this corresponds to humans, as well. | 0:19:45 | 0:19:49 | |

But there's good reason to suspect that it would. | 0:19:49 | 0:19:52 | |

Is serotonin created in the left side of the brain? | 0:19:52 | 0:19:54 | |

It's very, very interesting. | 0:19:54 | 0:19:56 | |

Alok, if people want to know more about the future, | 0:19:56 | 0:20:00 | |

we often ask you to find things for us to read. | 0:20:00 | 0:20:02 | |

There's a website here called worldometer. | 0:20:02 | 0:20:05 | |

It's full of data about the world right now | 0:20:05 | 0:20:07 | |

and the kinds of things you can find out are things like | 0:20:07 | 0:20:10 | |

current world population, number of births this year. | 0:20:10 | 0:20:13 | |

-You can see it going up bit by bit. -Number of births today. | 0:20:13 | 0:20:16 | |

-Even as we speak. -Deaths, of course. | 0:20:16 | 0:20:19 | |

There's more bicycles produced every year than cars which is good, | 0:20:19 | 0:20:23 | |

I suppose. Number of books published is a million or so this year. | 0:20:23 | 0:20:28 | |

And all of this information is actually updated | 0:20:28 | 0:20:31 | |

from genuine sources of information. | 0:20:31 | 0:20:33 | |

The United Nations and other reports like that. | 0:20:33 | 0:20:36 | |

-It's actually quite mesmerising. -Lovely stuff. | 0:20:36 | 0:20:38 | |

That's worldometer.info there. | 0:20:38 | 0:20:40 | |

Thank you very much, Molly. And thank you very much, Alok. | 0:20:40 | 0:20:43 | |

Still to come on tonight's show, what happens | 0:20:48 | 0:20:51 | |

when the earth's resources run out? | 0:20:51 | 0:20:53 | |

How will we dress ourselves in the future? | 0:20:56 | 0:20:59 | |

We check out the clothes made out of smart materials. | 0:20:59 | 0:21:02 | |

And the latest generation of humanoid robots. | 0:21:06 | 0:21:09 | |

And how they'll save lives. | 0:21:09 | 0:21:11 | |

When people talked of the future, along with hoverboards | 0:21:13 | 0:21:16 | |

and teleportation, we were also promised a form of life after death. | 0:21:16 | 0:21:20 | |

Cryonic suspension is the freezing procedure by which | 0:21:25 | 0:21:27 | |

we preserve patients after they have been pronounced legally dead | 0:21:27 | 0:21:31 | |

in the hope that at some future date medical science may be able | 0:21:31 | 0:21:34 | |

to restore them to active life, health and youth. | 0:21:34 | 0:21:37 | |

There are two whole body patients in this capsule, | 0:21:37 | 0:21:40 | |

plus one neuropreservation patient in which case only the head was | 0:21:40 | 0:21:43 | |

placed into suspension. | 0:21:43 | 0:21:45 | |

Medical science of the future should also be able to repair most | 0:21:45 | 0:21:48 | |

any freezing damage caused by the unperfected freezing techniques | 0:21:48 | 0:21:52 | |

that we currently use. | 0:21:52 | 0:21:53 | |

That was a man discussing cryonics back in the '60s. | 0:21:56 | 0:21:59 | |

I think it was 1969. It was very popular in the '60s | 0:21:59 | 0:22:01 | |

and '70s, the discussion of freezing yourself. | 0:22:01 | 0:22:04 | |

In fact, very recently, only a few weeks ago three Oxford academics | 0:22:04 | 0:22:07 | |

announced they wanted to freeze their heads for two of them. | 0:22:07 | 0:22:10 | |

One doing an entire body freezing | 0:22:10 | 0:22:11 | |

so that it would be somehow resurrected. | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

I think it's a scam, myself. | 0:22:14 | 0:22:16 | |

I think it's one of these things that they presume, 200 years, | 0:22:16 | 0:22:18 | |

people will have forgotten about them. We can tip them in a skip | 0:22:18 | 0:22:21 | |

at some stage. | 0:22:21 | 0:22:22 | |

It's also a no lose situation for them if they've got the money, I guess. | 0:22:22 | 0:22:25 | |

Possibly, they lose the money but it's after their death. | 0:22:25 | 0:22:29 | |

But it's no trivial matter to freeze someone and then return them. | 0:22:29 | 0:22:33 | |

The problem is that we're made mostly of water. 70% or 80% water. | 0:22:33 | 0:22:37 | |

And here's a carrot, also made mostly of water. | 0:22:37 | 0:22:39 | |

When you freeze something like this, as we all know, | 0:22:39 | 0:22:42 | |

when you freeze vegetables and then you defreeze them - | 0:22:42 | 0:22:44 | |

this is the idea of bringing them back to life - | 0:22:44 | 0:22:46 | |

they're not the same as they went in and... | 0:22:46 | 0:22:49 | |

AUDIENCE GROANS | 0:22:49 | 0:22:51 | |

-Oh, my Lord! -Lots of this water, where has it come from? | 0:22:51 | 0:22:54 | |

It's not the same as the one that went into the freezer. | 0:22:54 | 0:22:57 | |

And the reason is when you freeze something that is mostly water, | 0:22:57 | 0:23:01 | |

it turns to ice. | 0:23:01 | 0:23:02 | |

And ice does something weird to the cells that we're all made of | 0:23:02 | 0:23:05 | |

and that carrot is made of. | 0:23:05 | 0:23:06 | |

And that's who we are, these cells that interconnect. | 0:23:06 | 0:23:09 | |

Is it because the water expands as it becomes ice | 0:23:09 | 0:23:11 | |

and becomes too large for the cell? | 0:23:11 | 0:23:13 | |

Yeah. As the ice crystals form, they're basically disrupting | 0:23:13 | 0:23:16 | |

all the machinery inside the cells. | 0:23:16 | 0:23:18 | |

They can poke through the membrane, they can splinter the membranes. | 0:23:18 | 0:23:22 | |

All of that stuff comes out. | 0:23:22 | 0:23:23 | |

And the idea that you could freeze something like that and recover its | 0:23:23 | 0:23:27 | |

function later seems very fanciful, especially when you see this. | 0:23:27 | 0:23:30 | |

Let's just have a look at what freezing looks like | 0:23:30 | 0:23:32 | |

when crystals form. And her are some crystals of sodium acetate. | 0:23:32 | 0:23:36 | |

-I'm sort of giving it an opportunity to crystallise. -Right. | 0:23:36 | 0:23:39 | |

This is slow and you can see it. It's quite beautiful. | 0:23:39 | 0:23:42 | |

I hope. OK, ready? | 0:23:42 | 0:23:44 | |

-You can see it right there in the middle. -Oh, my God. | 0:23:46 | 0:23:49 | |

Imagine that is your cell and that crystal is forming. | 0:23:49 | 0:23:53 | |

It's basically disrupting the nucleus of the crystal. | 0:23:53 | 0:23:56 | |

It's maybe met the membrane and it's bursting through it. | 0:23:56 | 0:23:58 | |

This is not a good situation to be in if that's your head. | 0:23:58 | 0:24:01 | |

-That's beautiful. -It is beautiful. | 0:24:04 | 0:24:06 | |

That's maybe what they think as they're being frozen. | 0:24:06 | 0:24:09 | |

-Wow. -"This is wonderful, I can't wait to see the future." | 0:24:09 | 0:24:11 | |

Nope, turns out you're not going to see a future at all. | 0:24:11 | 0:24:14 | |

-That is absolutely lovely. -It is wonderful, isn't it? | 0:24:14 | 0:24:17 | |

There is a way round this. Or at least potentially. | 0:24:17 | 0:24:20 | |

That was slow and you got these very large crystals because of it. | 0:24:20 | 0:24:25 | |

As I was saying, they are mechanical objects | 0:24:25 | 0:24:27 | |

and they're going to do some stuff to you. | 0:24:27 | 0:24:29 | |

What if you could freeze it so fast that all of the crystals were tiny? | 0:24:29 | 0:24:32 | |

Really weenie ones. So actually they could be accommodated... | 0:24:32 | 0:24:36 | |

If you freeze so quickly they only have time to grow very tiny? | 0:24:36 | 0:24:40 | |

Tons of them form immediately and you get these tiny crystals. | 0:24:40 | 0:24:44 | |

And how would we achieve that? | 0:24:44 | 0:24:45 | |

Very, very cold stuff. | 0:24:45 | 0:24:47 | |

One of the things that these people are doing is being | 0:24:47 | 0:24:49 | |

plunged into liquid nitrogen. We've got some here. | 0:24:49 | 0:24:52 | |

First, let's just show people how fast you can freeze | 0:24:52 | 0:24:55 | |

something like a carrot. | 0:24:55 | 0:24:57 | |

At home you put this in the freezer and it would take several hours. | 0:24:57 | 0:25:00 | |

OK, grand. Hang on. There we go. Right. | 0:25:00 | 0:25:02 | |

You must think I'm obsessed with carrots but they are good for you. | 0:25:02 | 0:25:05 | |

-And in it goes. Now that's boiling the nitrogen. -Yep. | 0:25:05 | 0:25:12 | |

That object is much hotter than the boiling point of liquid nitrogen. | 0:25:12 | 0:25:15 | |

This stuff coming off here is not nitrogen. | 0:25:15 | 0:25:17 | |

You can't see it, it's an invisible gas. | 0:25:17 | 0:25:19 | |

This is the quite plentiful water vapour in the air | 0:25:19 | 0:25:22 | |

condensing to form a cloud. | 0:25:22 | 0:25:24 | |

But basically, liquid nitrogen is boiling off | 0:25:24 | 0:25:27 | |

and as a result that carrot is getting very cold, very fast. | 0:25:27 | 0:25:31 | |

That's been in for a minute now. Let's take it out. | 0:25:31 | 0:25:34 | |

That doesn't augur well for whoever paid 50 grand to freeze their head. | 0:25:34 | 0:25:37 | |

Obviously they won't do that. | 0:25:39 | 0:25:41 | |

That would be really offensive if they went, | 0:25:41 | 0:25:44 | |

"Oh, your uncle, yeah, he's here. | 0:25:44 | 0:25:45 | |

"There he is." | 0:25:45 | 0:25:46 | |

"How much of him do you want to bring home? He's there." | 0:25:46 | 0:25:49 | |

What can we possibly do to make a happy ending to this | 0:25:49 | 0:25:51 | |

particular item about tiny crystals? | 0:25:51 | 0:25:54 | |

Science is unsolved but one thing we can do with liquid nitrogen is make | 0:25:54 | 0:25:57 | |

tiny crystals and that improves the flavour and mouth feel of ice cream. | 0:25:57 | 0:26:02 | |

-Really? -Yes. -Heston's always doing this kind of nonsense. | 0:26:02 | 0:26:06 | |

What exactly is the science behind this? | 0:26:06 | 0:26:09 | |

If you think about it ice cream is basically cream, which is | 0:26:09 | 0:26:11 | |

mostly water with a bit of flavouring in it. | 0:26:11 | 0:26:13 | |

So when you freeze ice cream, you're making ice crystals. | 0:26:13 | 0:26:16 | |

And when you're eating ice cream you're eating ice. | 0:26:16 | 0:26:18 | |

But it doesn't taste crunchy, it doesn't taste mechanical. Why? | 0:26:18 | 0:26:21 | |

Because the crystals are tiny. | 0:26:21 | 0:26:23 | |

In order to get them really tiny | 0:26:23 | 0:26:24 | |

you have to constantly move them around and break them up. | 0:26:24 | 0:26:28 | |

Or you just put liquid nitrogen in and make tiny crystals | 0:26:28 | 0:26:31 | |

-in ten seconds. -OK. | 0:26:31 | 0:26:32 | |

And so this, in theory, should make very, very smooth ice cream. | 0:26:32 | 0:26:35 | |

-What is this? -This is cream with egg and a bit of vanilla. -All right. | 0:26:37 | 0:26:42 | |

Which is a traditional ice cream mix, I think you'll find. | 0:26:42 | 0:26:45 | |

Are you ready to go? | 0:26:45 | 0:26:46 | |

-OK. -You're going to pour that in and I'm going to mix it round. Go, go, go. | 0:26:46 | 0:26:51 | |

So the nitrogen is going in there, but it is immediately boiling off. | 0:26:51 | 0:26:54 | |

All the nitrogen is doing is cooling it off very fast. | 0:26:54 | 0:26:57 | |

-We're not adding nitrogen to the ice cream. -That's boiling off. | 0:26:57 | 0:27:00 | |

It's not our magic ingredient. | 0:27:00 | 0:27:02 | |

OK, that's great, that's great, I think. He says. | 0:27:02 | 0:27:05 | |

-Is that working? -Yeah. I think so. | 0:27:07 | 0:27:11 | |

It's a hell of a visual effect you've created anyway. | 0:27:11 | 0:27:13 | |

I've got an ice cream scoop over here. | 0:27:17 | 0:27:19 | |

# Just one... # | 0:27:19 | 0:27:20 | |

Here we go. | 0:27:20 | 0:27:23 | |

-Didn't get that reference. -No, I got it. | 0:27:23 | 0:27:26 | |

Traditionally on television programmes they taste a thing | 0:27:30 | 0:27:33 | |

and go... | 0:27:33 | 0:27:34 | |

DARA MUMBLES | 0:27:34 | 0:27:35 | |

Unless it's MasterChef in which they go... | 0:27:35 | 0:27:39 | |

I'm getting the nitrogen. | 0:27:39 | 0:27:41 | |

-Are you? -It tastes very nitrogen-y. | 0:27:41 | 0:27:43 | |

It's very rocky and icy this. Does it have to melt a little bit? | 0:27:43 | 0:27:48 | |

-It's frozen solid. -It should be smooth. | 0:27:48 | 0:27:49 | |

It's not smooth in the slightest, look. | 0:27:49 | 0:27:52 | |

-You put too much nitrogen in. -Who was in charge of the nitrogen? | 0:27:53 | 0:27:57 | |

You were supposed to say when for God's sake. I'm not a chef. | 0:27:57 | 0:28:00 | |

-Let's let the audience... Yeah, yeah. -Do you want a go? | 0:28:00 | 0:28:05 | |

Hello, madam, how are you? Yes, you, the one standing at the front. | 0:28:05 | 0:28:09 | |

Go on then you, come on. | 0:28:09 | 0:28:11 | |

How much did you want that? You were pushing. You were stepping in. | 0:28:16 | 0:28:22 | |

I'll grab you as well, sir. Come in as well. Thank you very much. | 0:28:22 | 0:28:25 | |

Here, you take that. | 0:28:25 | 0:28:28 | |

There we go. Now, do you find it rocky and icy like I do? | 0:28:28 | 0:28:32 | |

-And thus unpalatable and not nice? -Like an outer planet. | 0:28:32 | 0:28:35 | |

-It's good. It's melted a bit. -It's melted a bit. -It is very smooth. | 0:28:35 | 0:28:40 | |

It's hard on the outside but microscopically very smooth. | 0:28:40 | 0:28:44 | |

Loving this guy. That's exactly what we want to hear. | 0:28:44 | 0:28:47 | |

-Well said. -Nobody has ever on MasterChef gone, | 0:28:47 | 0:28:50 | |

"Microscopically smooth." | 0:28:50 | 0:28:52 | |

Delicious, OK. | 0:28:52 | 0:28:54 | |

If you want to get involved and try some of Mark's experiments at home - | 0:28:54 | 0:28:58 | |

maybe this one isn't the first one to try out - | 0:28:58 | 0:29:01 | |

there are some step-by-step instructions on the website.... | 0:29:01 | 0:29:03 | |

Thank you very much, Mark. It was very good. | 0:29:06 | 0:29:09 | |

We carry around with us a lot of very sophisticated | 0:29:12 | 0:29:15 | |

materials in our pockets and our bags. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:16 | |

The stuff, for example, that makes up our own personal technology. | 0:29:16 | 0:29:19 | |

A question for yourselves in the audience, how many minerals, | 0:29:19 | 0:29:22 | |

specifically rare earth metals, do you think are used to make | 0:29:22 | 0:29:26 | |

an iPhone? Any guesses? | 0:29:26 | 0:29:27 | |

-AUDIENCE SHOUTS NUMBERS -10, 50, four that man goes. | 0:29:27 | 0:29:31 | |

-100. -100. I'm not even sure there are 100 rare earth metals. | 0:29:31 | 0:29:36 | |

There are nine and where do 90% of these rare earth minerals come from? | 0:29:36 | 0:29:41 | |

China, you're absolutely right. We've got a really smart crowd. | 0:29:41 | 0:29:44 | |

China is where they come from which is handy | 0:29:44 | 0:29:47 | |

because that's where the phones are made. | 0:29:47 | 0:29:49 | |

However, we do not have an endless supply of these materials. | 0:29:49 | 0:29:52 | |

But help could be at hand, as unlikely as it may seem | 0:29:52 | 0:29:54 | |

there are people planning to mine the surface of the moon. | 0:29:54 | 0:29:57 | |

Mark's been to find out | 0:29:57 | 0:29:59 | |

if this audacious plan could ever actually work. | 0:29:59 | 0:30:02 | |

Asteroids are some of the richest sources of metals | 0:30:04 | 0:30:07 | |

in the solar system. | 0:30:07 | 0:30:08 | |

And that means the moon, which has been bombarded by asteroids, | 0:30:10 | 0:30:14 | |

will have billions of years' worth of asteroidal metal | 0:30:14 | 0:30:17 | |

lying in the dirt for the taking. | 0:30:17 | 0:30:19 | |

Most of the heavy metals we mine here on earth | 0:30:22 | 0:30:25 | |

were also dumped here by asteroid impacts. | 0:30:25 | 0:30:29 | |

At a mining facility in North Ontario, | 0:30:29 | 0:30:31 | |

they're pioneering sampling equipment for the next wild frontier - | 0:30:31 | 0:30:35 | |

mining the moon. | 0:30:35 | 0:30:36 | |

But is moon mining really feasible? | 0:30:38 | 0:30:41 | |

Why aren't we already up there blasting away at the rock? | 0:30:41 | 0:30:44 | |

RUMBLING | 0:30:45 | 0:30:48 | |

This is how mining works on earth. Huge explosions. | 0:30:48 | 0:30:51 | |

RUMBLING | 0:30:51 | 0:30:53 | |

God, I can feel it coming towards me. | 0:30:53 | 0:30:55 | |

We've always used brute force - enormous drills, machines. | 0:30:55 | 0:30:59 | |

But that won't necessarily work on the moon. | 0:31:01 | 0:31:04 | |

Asteroids hitting the moon would have had their metals | 0:31:04 | 0:31:06 | |

vaporised on impact, scattering far and wide through the lunar soil. | 0:31:06 | 0:31:11 | |

So why don't we simply go and scoop up the loose stuff on the surface? | 0:31:11 | 0:31:15 | |

Even that is easier said than done. | 0:31:16 | 0:31:18 | |

Machines for digging on the moon have to deal with dust that | 0:31:20 | 0:31:22 | |

behaves like none you'll ever see on earth. | 0:31:22 | 0:31:24 | |

That's why director of development Dale Boucher | 0:31:27 | 0:31:30 | |

tests lunar samplers on his own simulated moon dust. | 0:31:30 | 0:31:33 | |

So if I was to just sort of plunge this thing into it... | 0:31:34 | 0:31:37 | |

This is sort of dusty on the surface... | 0:31:39 | 0:31:43 | |

It kind of gets solid. | 0:31:43 | 0:31:45 | |

It's just a bit of an odd material. | 0:31:45 | 0:31:47 | |

This material compacts very quickly with depth. | 0:31:47 | 0:31:50 | |

The first ten centimetres is a fine powdery material. | 0:31:50 | 0:31:53 | |

Once you get below that, it hardens up very quickly. | 0:31:53 | 0:31:56 | |

Scooping up moon dust poses another problem you don't get on earth. | 0:31:56 | 0:32:00 | |

Areas in full sunlight will look like this. | 0:32:00 | 0:32:03 | |

'But only a few metres away in permanent shadow, | 0:32:03 | 0:32:06 | |

'it could be frozen solid and over 200 degrees colder.' | 0:32:06 | 0:32:10 | |

God. It'd be terrible to be sent to the moon with a scoop and go... | 0:32:12 | 0:32:15 | |

-HE LAUGHS -That's right, "Now what do I do?" | 0:32:15 | 0:32:17 | |

'Whether you're digging or drilling, | 0:32:17 | 0:32:19 | |

'you go equipped if you want to tackle moon dust. | 0:32:19 | 0:32:22 | |

'But that presents another problem, because flying heavy machinery | 0:32:22 | 0:32:26 | |

'up to the moon is the last thing you want to do.' | 0:32:26 | 0:32:28 | |

Launching and landing, soft landing, | 0:32:28 | 0:32:31 | |

something on the moon is very expensive. | 0:32:31 | 0:32:33 | |

Rough magnitude of 250,000 US | 0:32:33 | 0:32:36 | |

to land a one litre of bottle of water on the moon. | 0:32:36 | 0:32:39 | |

-That's an expensive drink. -It is very expensive. | 0:32:39 | 0:32:42 | |

Even though the technology to harvest lunar soil is real, | 0:32:43 | 0:32:47 | |

it seems the odds are stacked against doing it cheaply. | 0:32:47 | 0:32:51 | |

Mining the surface deposits of the moon is clearly possible, | 0:32:51 | 0:32:53 | |

but it would have to compete with terrestrial mining. | 0:32:53 | 0:32:56 | |

This stuff - it's huge, it's big business. | 0:32:56 | 0:32:59 | |

Bearing in mind that it costs hundreds of thousands of dollars | 0:32:59 | 0:33:02 | |

to transport one kilogram of stuff from the moon to the earth, | 0:33:02 | 0:33:05 | |

the question is - would it ever be economically viable? | 0:33:05 | 0:33:08 | |

You could save on shipping raw materials back to earth | 0:33:10 | 0:33:13 | |

by processing metals in situ. | 0:33:13 | 0:33:14 | |

But here that usually involves burning fossil fuels | 0:33:15 | 0:33:18 | |

to smelt the ore. You can forget that on the moon. | 0:33:18 | 0:33:22 | |

But new developments in electrolysis could transform | 0:33:23 | 0:33:26 | |

the viability of moon mining. | 0:33:26 | 0:33:27 | |

Passing electricity through molten rock can draw the metals out. | 0:33:31 | 0:33:36 | |

At MIT in Boston, | 0:33:36 | 0:33:37 | |

Professor Antoine Allanore's team are pioneering | 0:33:37 | 0:33:41 | |

ways to reach incredibly high temperatures | 0:33:41 | 0:33:43 | |

using nothing more than the power of light. | 0:33:43 | 0:33:46 | |

Dr Guillaume Lambotte melts metal ore with highly focused xenon lamps. | 0:33:46 | 0:33:52 | |

Electrolysis leaves behind a blob of pure nickel. | 0:33:53 | 0:33:57 | |

In this case this is xenon lamp, | 0:33:58 | 0:34:00 | |

but you could use maybe a laser as a source or even sun. | 0:34:00 | 0:34:04 | |

You don't need to bring additional energy into space. | 0:34:04 | 0:34:07 | |

You're basically using what's available over there. | 0:34:07 | 0:34:10 | |

Antoine's metal extraction could be powered by something that's | 0:34:10 | 0:34:13 | |

always free in space - sunlight. | 0:34:13 | 0:34:17 | |

Not only that, but electrolysis has a by-product that's | 0:34:17 | 0:34:19 | |

worthless on earth, but priceless out there. | 0:34:19 | 0:34:22 | |

Oxygen. | 0:34:24 | 0:34:26 | |

Suddenly the idea of a mining base on the moon seems much more viable. | 0:34:26 | 0:34:31 | |

Dr Lewis Dartnell works for the UK Space Agency. | 0:34:34 | 0:34:38 | |

What's really exciting is the waste product from this process, | 0:34:39 | 0:34:42 | |

the oxygen on the moon is incredibly valuable commodity itself | 0:34:42 | 0:34:45 | |

because you can use it for astronauts for breathing. | 0:34:45 | 0:34:48 | |

And so with metals from the lunar dust | 0:34:48 | 0:34:50 | |

and oxygen from the lunar dust, you've basically got | 0:34:50 | 0:34:53 | |

everything you need to start building self-sustaining habitats. | 0:34:53 | 0:34:56 | |

I mean, you're literally living off the land. | 0:34:56 | 0:34:59 | |

So it's not an outlandish proposition, really - | 0:34:59 | 0:35:01 | |

mining the moon and creating a self-sufficient lunar base. | 0:35:01 | 0:35:03 | |

It sort of feels like all the ingredients are there. | 0:35:03 | 0:35:06 | |

There's problems still to be solved, of course there are. | 0:35:06 | 0:35:08 | |

Economics need to be worked out, but in broad brush strokes I think | 0:35:08 | 0:35:11 | |

we understand pretty well how to do it. | 0:35:11 | 0:35:13 | |

In terms of future resources, the real value of moon mining is | 0:35:13 | 0:35:17 | |

so much more than just a source of raw materials. | 0:35:17 | 0:35:20 | |

A self-sufficient mining base would give us | 0:35:20 | 0:35:23 | |

our first home away from home in the solar system. | 0:35:23 | 0:35:26 | |

And the potential rewards from that are astronomical. | 0:35:26 | 0:35:30 | |

So what you're saying, Mark, is this an economic question? | 0:35:36 | 0:35:38 | |

It'll only be done when it's cheaper to get it from the moon | 0:35:38 | 0:35:41 | |

than it is to try digging it out from the earth. | 0:35:41 | 0:35:44 | |

I think the real question is - will we ever really afford | 0:35:44 | 0:35:47 | |

the minerals we can get on the moon to bring them back to the earth? | 0:35:47 | 0:35:50 | |

Probably they'll be more valuable out there, because we all want to explore | 0:35:50 | 0:35:53 | |

the rest of the solar system. It'd be the perfect place to do it. | 0:35:53 | 0:35:56 | |

We would use that, we would mine there in order to | 0:35:56 | 0:35:58 | |

create the rockets and to head off from there. | 0:35:58 | 0:36:02 | |

It's got all the ingredients. I mean, we can get the oxygen, | 0:36:02 | 0:36:04 | |

we can get the metals we can get the water... | 0:36:04 | 0:36:07 | |

We're pretty sure we can get the water there. | 0:36:07 | 0:36:09 | |

We can have a self-sufficient base there and use it as a base | 0:36:09 | 0:36:11 | |

to explore the solar system. | 0:36:11 | 0:36:12 | |

And also, there is helium-3 on the moon, | 0:36:12 | 0:36:15 | |

if you take a look at scans of the moon. | 0:36:15 | 0:36:17 | |

And helium-3 is rather interesting because some people theorise | 0:36:17 | 0:36:21 | |

that it can be used as a fuel for fusion reactors of the future. | 0:36:21 | 0:36:25 | |

Most people would just think of helium | 0:36:25 | 0:36:27 | |

in terms of balloons at a kid's party. | 0:36:27 | 0:36:29 | |

Helium's... Helium's used in MRI scanners? | 0:36:29 | 0:36:32 | |

Yeah, I mean helium, if we run out of helium it's a really big problem. | 0:36:32 | 0:36:35 | |

It's the best refrigerant we've got. | 0:36:35 | 0:36:38 | |

Basically, all that diagnostic equipment in hospitals | 0:36:38 | 0:36:40 | |

is all cooled using helium. | 0:36:40 | 0:36:43 | |

Actually, it's a finite supply cos when it goes out of your balloon | 0:36:43 | 0:36:47 | |

or it comes out of the machine, it has escape velocity. | 0:36:47 | 0:36:50 | |

It goes into space. So we are losing... | 0:36:50 | 0:36:52 | |

It's the only atom species that's going out of the earth. | 0:36:52 | 0:36:55 | |

-It leaves the earth's orbit? -Yeah. | 0:36:55 | 0:36:57 | |

The balloon that you get at a kid's party... | 0:36:57 | 0:36:59 | |

Not the balloon, the helium does. | 0:36:59 | 0:37:01 | |

Obviously not the balloon, that would be weird. | 0:37:01 | 0:37:03 | |

Space were filled with Peppa Pig balloons moving around. | 0:37:03 | 0:37:07 | |

-But when you do that... -HE INHALES AND SPEAKS IN A HIGH PITCH | 0:37:07 | 0:37:10 | |

..that just...? | 0:37:10 | 0:37:11 | |

That helium is going to end up in space, very likely. | 0:37:11 | 0:37:14 | |

My God, it's astonishing. How many years? | 0:37:14 | 0:37:16 | |

What's the worst estimate that we have | 0:37:16 | 0:37:18 | |

in terms of running out of helium? | 0:37:18 | 0:37:20 | |

Well, you know, we disagree and other people do too. | 0:37:20 | 0:37:23 | |

50 years is a time frame that's likely, | 0:37:23 | 0:37:28 | |

100 years - very, very likely. | 0:37:28 | 0:37:31 | |

Look, thank you very much, Mark and Dr Michio Kaku. | 0:37:31 | 0:37:33 | |

APPLAUSE | 0:37:33 | 0:37:35 | |

Now here with this week's science news is Helen. | 0:37:38 | 0:37:41 | |

Now we know that light is important when you're growing crops, | 0:37:45 | 0:37:48 | |

but it's just been discovered that it can be used to change their flavour. | 0:37:48 | 0:37:52 | |

This team of scientists in Florida put harvested fruit under | 0:37:52 | 0:37:55 | |

different colours of light. | 0:37:55 | 0:37:57 | |

And what they found is that the different wavelengths affected | 0:37:57 | 0:38:01 | |

the molecules for taste and smell. | 0:38:01 | 0:38:04 | |

We could see this technology in our supermarkets | 0:38:04 | 0:38:06 | |

and even in our fridges to get the most out of our fruit and veg. | 0:38:06 | 0:38:09 | |

The search for alternative energy sources is relentless | 0:38:13 | 0:38:16 | |

and this week's is really bizarre. | 0:38:16 | 0:38:19 | |

This is a fuel cell and it may sound weird, but it runs entirely on urine. | 0:38:19 | 0:38:25 | |

As urine goes through these tubes here, | 0:38:25 | 0:38:27 | |

it's broken down by a cocktail of bacteria to generate electricity. | 0:38:27 | 0:38:31 | |

There's no shortage of urine, even in remote places. | 0:38:31 | 0:38:35 | |

Fuel cells like this could be used to power everything | 0:38:35 | 0:38:38 | |

from lights to mobile phones. | 0:38:38 | 0:38:39 | |

A spider's web is one of nature's deadliest traps | 0:38:44 | 0:38:47 | |

and now scientists have discovered why some are so effective. | 0:38:47 | 0:38:50 | |

And they've caught it on film for the first time. | 0:38:50 | 0:38:53 | |

As insects fly, the movement of their wings builds up positive charge | 0:38:54 | 0:38:59 | |

and that draws the web towards it. | 0:38:59 | 0:39:01 | |

As you can see, the moment the two touch | 0:39:03 | 0:39:06 | |

it's all over for the fly. | 0:39:06 | 0:39:07 | |

Still to come - | 0:39:11 | 0:39:12 | |

we discover how kind or otherwise the future will be to us. | 0:39:12 | 0:39:16 | |

-There you are. -What?! | 0:39:16 | 0:39:18 | |

What the hell...? | 0:39:18 | 0:39:19 | |

Hi-five. | 0:39:21 | 0:39:22 | |

And Alok makes new friends with the latest robots. | 0:39:22 | 0:39:25 | |

What you do is straighten your hand slightly. | 0:39:25 | 0:39:27 | |

GRASPY: It's a pleasure to meet you, Alok. | 0:39:27 | 0:39:29 | |

Whenever we do a show about the future, | 0:39:30 | 0:39:32 | |

we are haunted by the predictions of televisions shows past. | 0:39:32 | 0:39:36 | |

Check out this fantastic clip from Tomorrow's World from 1965. | 0:39:36 | 0:39:40 | |

Tomorrow's girl could well look something like this. | 0:39:40 | 0:39:44 | |

On her head, no hair - a nylon wig. | 0:39:44 | 0:39:47 | |

Just a quick wipe with a damp cloth and your head's as good as new. | 0:39:47 | 0:39:51 | |

You notice the shirt with no collar, but that is made of paper. | 0:39:51 | 0:39:56 | |

Just the thing for jotting down telephone numbers. | 0:39:56 | 0:39:59 | |

In fact, you could make notes all over yourself. | 0:39:59 | 0:40:02 | |

The jacket and skirt are in plastic. | 0:40:02 | 0:40:05 | |

The sort of material that they used for covering kitchen tables | 0:40:06 | 0:40:11 | |

not so very long ago. | 0:40:11 | 0:40:13 | |

And if the synthetic weather should prove unreliable, | 0:40:13 | 0:40:17 | |

then we have a plastic Mackintosh with these extremely | 0:40:17 | 0:40:22 | |

interesting transparent pockets | 0:40:22 | 0:40:25 | |

to discourage you from loading them up with all sorts of junk. | 0:40:25 | 0:40:28 | |

LAUGHTER | 0:40:28 | 0:40:29 | |

All the pockets are transparent now. That's the way... | 0:40:32 | 0:40:34 | |

That's just the way that fashion has gone. | 0:40:34 | 0:40:36 | |

We are now...offer a hostage to the same kind of fortune. | 0:40:36 | 0:40:39 | |

This is the bit that will be shown in clips on science programmes | 0:40:39 | 0:40:42 | |

in another 40 or 50 years' time. | 0:40:42 | 0:40:44 | |

We're not going to predict fashion but fabrics | 0:40:44 | 0:40:47 | |

-and modern contemporary fabrics, they will change. -Yes. | 0:40:47 | 0:40:50 | |

So this is an opalescent material mimicking the colours | 0:40:50 | 0:40:53 | |

and the opalelescence of a butterfly wing. And in exactly the same way. | 0:40:53 | 0:40:56 | |

So those are not pigments. Light doesn't hit it and is absorbed | 0:40:56 | 0:40:59 | |

and reflected off at a particular pigment, | 0:40:59 | 0:41:01 | |

but actually there are little platelets in a butterfly's wing | 0:41:01 | 0:41:04 | |

which basically selectively reflect different wavelengths | 0:41:04 | 0:41:07 | |

and interfere with each other. | 0:41:07 | 0:41:09 | |

And therefore you get this slightly changing angle and iridescence. | 0:41:09 | 0:41:12 | |

In this fabric, they're done with little polystyrene balls, | 0:41:12 | 0:41:15 | |

so the distance between them is the colour you see. | 0:41:15 | 0:41:17 | |

-So you can change that distance by stretching it. -Oh, yeah. | 0:41:17 | 0:41:20 | |

-This is very good. -This is one over on the butterfly. | 0:41:20 | 0:41:22 | |

This is green, right. We're green. And then blue. | 0:41:22 | 0:41:25 | |

How great is that? | 0:41:25 | 0:41:26 | |

I mean, somebody said the best use for that is if you're getting fat. | 0:41:26 | 0:41:29 | |

LAUGHTER | 0:41:29 | 0:41:30 | |

As you get fatter, the colours you wear change and... | 0:41:30 | 0:41:34 | |

Looking a bit blue today, John. | 0:41:34 | 0:41:37 | |

That kind of way, OK. | 0:41:37 | 0:41:38 | |

-So it's an opalescent material. -Yeah. -A wearable opalescence. | 0:41:38 | 0:41:41 | |

But I think that the interesting thing about this is | 0:41:41 | 0:41:44 | |

just that the microstructural control | 0:41:44 | 0:41:46 | |

now that's coming into fabrics and textiles, | 0:41:46 | 0:41:48 | |

these things called technical textiles. | 0:41:48 | 0:41:49 | |

All electronics are being filtered into there, | 0:41:49 | 0:41:52 | |

so you're going to see a much more responsive | 0:41:52 | 0:41:54 | |

interesting smart-wearing materials. | 0:41:54 | 0:41:57 | |

React to light or sound or...? | 0:41:57 | 0:41:59 | |

Yeah, so there's things called electroluminescent materials | 0:41:59 | 0:42:01 | |

and these are essentially pigments that | 0:42:01 | 0:42:03 | |

when you run an electric current through them, they give off light. | 0:42:03 | 0:42:07 | |

-Oh, hello. -There it is. -Wow, that's amazing. -This is zinc sulphide. | 0:42:07 | 0:42:10 | |

That is just incredibly... That is just a strip of laminated card. | 0:42:10 | 0:42:13 | |

It's really flat. | 0:42:13 | 0:42:14 | |

And it's bendy and... You can't see where the light's produced. | 0:42:14 | 0:42:18 | |

It's a very even light. | 0:42:18 | 0:42:20 | |

So this is not really a fabric yet, but it's getting there. | 0:42:20 | 0:42:23 | |

So the idea of the clothes that can light up, well, | 0:42:23 | 0:42:25 | |

this seems one of the good candidates for that. | 0:42:25 | 0:42:28 | |

And in fact there's a British designer, Amy Winters, | 0:42:28 | 0:42:31 | |

who's here tonight and she's lent us one of her dresses, | 0:42:31 | 0:42:33 | |

which features these materials in her dresses. | 0:42:33 | 0:42:35 | |

-This is Izzy who is going to model. -Izzy, how are you? | 0:42:35 | 0:42:37 | |

What are we combining with from Izzy here? | 0:42:37 | 0:42:39 | |

I'll just plug you in. | 0:42:39 | 0:42:41 | |

The one downside of this stuff is that it needs quite a high voltage. | 0:42:41 | 0:42:43 | |

It's not a high current but a high voltage. | 0:42:43 | 0:42:45 | |

Although you can have your battery packs, | 0:42:45 | 0:42:47 | |

they wear out quite quickly. Now, here we go. | 0:42:47 | 0:42:49 | |

Actually, this dress also reacts to music | 0:42:49 | 0:42:53 | |

and does different things depending on the different volumes. | 0:42:53 | 0:42:55 | |

So is that reacting to your voice at the moment? | 0:42:55 | 0:42:57 | |

It seems to be, actually. I was a bit surprised by that. | 0:42:57 | 0:43:00 | |

OK, well, that seems a bit unformed. | 0:43:00 | 0:43:02 | |

Let's bring some music in. Play some music, please. | 0:43:02 | 0:43:06 | |

DRUMMING | 0:43:06 | 0:43:07 | |

So you get these different panels lighting up | 0:43:09 | 0:43:11 | |

depending on the volume level. | 0:43:11 | 0:43:12 | |

That's quite good, that's quite good. | 0:43:17 | 0:43:19 | |

The other thing I like about this a lot is that you're at a party, | 0:43:19 | 0:43:22 | |

you don't want people to invade your personal space. | 0:43:22 | 0:43:25 | |

This does that for you. Keep away. But also, you know... | 0:43:25 | 0:43:28 | |

Essentially, you put on a light and floor show | 0:43:28 | 0:43:31 | |

and you put on a huge demonstration, but... | 0:43:31 | 0:43:33 | |

It says, "Come to me, but not too close." | 0:43:33 | 0:43:35 | |

You impale them on the giant spikes of the dress. | 0:43:35 | 0:43:38 | |

You're bringing them in, you're pushing them out. | 0:43:38 | 0:43:40 | |

Thank you, Izzy. | 0:43:40 | 0:43:41 | |

Look forward to whatever party you have to carry around | 0:43:41 | 0:43:43 | |

your own battery pack to attend. It's going to be very, very good. | 0:43:43 | 0:43:47 | |

I'm not sure how practical that is, | 0:43:50 | 0:43:52 | |

but it'll make great viewing in 50 years' time. | 0:43:52 | 0:43:54 | |

Our childhoods were full of exciting information of what the future | 0:43:54 | 0:43:57 | |

would look like and we were always assured that we'd be sharing | 0:43:57 | 0:44:00 | |

that future with robots. That, of course, has never happened. | 0:44:00 | 0:44:03 | |

But has their time finally come. | 0:44:03 | 0:44:04 | |

Alok has been to not one | 0:44:04 | 0:44:06 | |

but two universities in Philadelphia in search of our future robots. | 0:44:06 | 0:44:09 | |

And he's finding new generations of machines - ones that can cope | 0:44:09 | 0:44:12 | |

with the mess and the unpredictability of the real world. | 0:44:12 | 0:44:15 | |

Could the future be robots like Graspy? | 0:44:21 | 0:44:24 | |

Oh, he is a happy robot. | 0:44:26 | 0:44:28 | |

He's the brain child of robot enthusiast | 0:44:28 | 0:44:30 | |

Professor Katherine Kuchenbecker. | 0:44:30 | 0:44:32 | |

Hi, Graspy. How are you doing today? | 0:44:32 | 0:44:34 | |

-It's a him, by the way, is it? -Well, yeah, Graspy is a him. | 0:44:34 | 0:44:38 | |

-GRASPY: -What is your name? | 0:44:38 | 0:44:40 | |

-My name's Alok. -It's a pleasure to meet you, Alok. | 0:44:40 | 0:44:44 | |

You've got a wonderful accent. | 0:44:44 | 0:44:46 | |

Let's begin. | 0:44:46 | 0:44:48 | |

He can talk, he can see. | 0:44:48 | 0:44:50 | |

But above all, Graspy has sensors that give him | 0:44:50 | 0:44:53 | |

touch which make him much more useful than your average robot. | 0:44:53 | 0:44:57 | |

All right, Graspy. Pick the cup up without using your touch sensors. | 0:44:57 | 0:45:01 | |

-Oh! -Well, there we go, look. | 0:45:02 | 0:45:05 | |

'Turn the sensors back on and it's a whole different story.' | 0:45:05 | 0:45:09 | |

All right. | 0:45:09 | 0:45:10 | |

Maybe give it to Alok. | 0:45:10 | 0:45:12 | |

Thank you very much. | 0:45:14 | 0:45:16 | |

-Now. Thanks, Graspy. -That was perfect. -Very good. | 0:45:16 | 0:45:20 | |

'It might not look like much | 0:45:22 | 0:45:23 | |

'but Graspy's sensitivity to subtle objects is a giant leap forward.' | 0:45:23 | 0:45:28 | |

When it first touches the object, | 0:45:28 | 0:45:29 | |

it's able to figure out how hard to squeeze...and then it comes over here | 0:45:29 | 0:45:33 | |

and when the cup hits the table, it recognises that and lets it go. | 0:45:33 | 0:45:36 | |

I mean it's impressive. | 0:45:36 | 0:45:37 | |

-Yes, well, it does what you would expect it to do. -Yeah, that's right. | 0:45:37 | 0:45:40 | |

That's what robots in movies do, they don't crush things. Why would they? | 0:45:40 | 0:45:44 | |

Why indeed? But I'm told he's got an even more impressive trick. | 0:45:44 | 0:45:49 | |

One that makes him alarmingly human. | 0:45:49 | 0:45:53 | |

He can extract touchy-feely information in exactly | 0:45:53 | 0:45:56 | |

the same way that we do. | 0:45:56 | 0:45:59 | |

Hmmm, what does that feel like? | 0:45:59 | 0:46:03 | |

-GRASPY: -Squishy, compressible and soft. | 0:46:03 | 0:46:06 | |

-BOTH: -Squishy, compressible... -and soft. | 0:46:06 | 0:46:10 | |

Wow, it's not often you get a robot's view of our world. | 0:46:10 | 0:46:13 | |

Catherine gave Graspy a variety of surfaces to feel and then | 0:46:15 | 0:46:19 | |

taught him the wide range of words that we use to describe them. | 0:46:19 | 0:46:23 | |

-GRASPY: -Soft, squishy, hairy, scratchy and unpleasant. | 0:46:23 | 0:46:27 | |

-Soft, squishy, hairy, scratchy... -Scratchy, unpleasant. -Unpleasant. | 0:46:27 | 0:46:32 | |

Oh, Graspy, you didn't like it? | 0:46:32 | 0:46:35 | |

And then he learned the connections, | 0:46:35 | 0:46:36 | |

to deduce the meaning of these adjectives. | 0:46:36 | 0:46:39 | |

So you taught Graspy these words... | 0:46:39 | 0:46:41 | |

-Yes. -..and then he learnt what those mean in terms of sensation? -Yeah. | 0:46:41 | 0:46:45 | |

Catherine's elegant software and Graspy's uniquely sensitive | 0:46:45 | 0:46:48 | |

fingers have given him an amazing sense of touch. | 0:46:48 | 0:46:52 | |

It's an essential attribute but that alone isn't | 0:46:52 | 0:46:55 | |

going to deliver our humanoid robot of the future. | 0:46:55 | 0:46:58 | |

We want more from our robots | 0:46:58 | 0:47:00 | |

and a growing number of researchers are working on it. | 0:47:00 | 0:47:03 | |

The scientists at Drexel University have set themselves | 0:47:03 | 0:47:06 | |

an even more difficult challenge. | 0:47:06 | 0:47:08 | |

They're designing a robot that can think like us. | 0:47:08 | 0:47:12 | |

This is Hubo. | 0:47:17 | 0:47:19 | |

No-one has directly programmed him | 0:47:19 | 0:47:22 | |

and no-one is remotely controlling him. | 0:47:22 | 0:47:24 | |

He's learning to think for himself. | 0:47:24 | 0:47:27 | |

He's in training for the DARPA Challenge. | 0:47:27 | 0:47:30 | |

The US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, DARPA, | 0:47:30 | 0:47:34 | |

has challenged technologists to build a robot that can | 0:47:34 | 0:47:37 | |

operate independently | 0:47:37 | 0:47:39 | |

somewhere we can't go, like a nuclear disaster zone, | 0:47:39 | 0:47:42 | |

and the prize is 2,000,000. | 0:47:42 | 0:47:45 | |

This is what they'd love Hubo to look like with his best suit on. | 0:47:45 | 0:47:50 | |

He's a strong contender to win, but in reality, | 0:47:50 | 0:47:53 | |

he's still very much a work in progress. | 0:47:53 | 0:47:56 | |

In some ways, being able to walk or use tools is something | 0:47:56 | 0:48:00 | |

you would've expected robots to do quite a long time ago | 0:48:00 | 0:48:03 | |

but all these actions, all these movements that we make, | 0:48:03 | 0:48:07 | |

they're incredibly hard for robots to replicate. | 0:48:07 | 0:48:10 | |

We take them completely for granted. | 0:48:10 | 0:48:12 | |

Let's take a really simple action, for example. | 0:48:12 | 0:48:14 | |

Shall we try a high five, Hubo? | 0:48:14 | 0:48:17 | |

Let's give it a go. | 0:48:17 | 0:48:18 | |

Ah, not bad. | 0:48:18 | 0:48:20 | |

You could probably do with straightening your hand slightly, | 0:48:20 | 0:48:22 | |

a bit more force. It's not too bad. | 0:48:22 | 0:48:24 | |

Hubo can mimic my hand action | 0:48:24 | 0:48:27 | |

but what about the supreme balancing act that we perform every day? | 0:48:27 | 0:48:31 | |

Walking on two feet - a nightmare for a robot. | 0:48:31 | 0:48:35 | |

But our world is built for us. | 0:48:35 | 0:48:37 | |

If Hubo's going to be any use in a human crisis, | 0:48:37 | 0:48:40 | |

he'll have to walk like us. | 0:48:40 | 0:48:43 | |

And there we go. Now, that's a normal walk, but it's...whoa! | 0:48:43 | 0:48:49 | |

Falling over, a lot, is exactly how we learn to walk. | 0:48:49 | 0:48:54 | |

But, for Hubo, there's added stress. | 0:48:54 | 0:48:56 | |

He has to learn to cope with the debris of a nuclear explosion. | 0:48:56 | 0:49:00 | |

They're trying to pack years of human learning into a robot | 0:49:00 | 0:49:03 | |

that was "born" just weeks ago. | 0:49:03 | 0:49:06 | |

Yet, spurred on by the DARPA Challenge, they are making progress. | 0:49:07 | 0:49:12 | |

Hubo must also learn how to drive a vehicle in a disaster zone. | 0:49:24 | 0:49:28 | |

Just getting into one is proving difficult enough. | 0:49:31 | 0:49:34 | |

It's not like this thing's got a brain like Einstein, | 0:49:37 | 0:49:40 | |

it's not even Dara O'Briain, let's be honest, but the thing is | 0:49:40 | 0:49:43 | |

it's doing all these things that we unconsciously do. | 0:49:43 | 0:49:46 | |

In fact, most of what we do every day is second nature to us, | 0:49:47 | 0:49:51 | |

it's in our subconscious. | 0:49:51 | 0:49:54 | |

If robots like Hubo are going to be part of our future, | 0:49:54 | 0:49:57 | |

they'll have to understand that. | 0:49:57 | 0:49:59 | |

It's a really important part of thinking like a human being. | 0:49:59 | 0:50:03 | |

The team have until the end of 2014 | 0:50:03 | 0:50:05 | |

to perfect Hubo for the DARPA Robotic Challenge. | 0:50:05 | 0:50:09 | |

If they win, we may be a step closer to having a functioning, | 0:50:09 | 0:50:13 | |

and possibly even useful, fully-autonomous robot. | 0:50:13 | 0:50:17 | |

It's very exciting, it's very exciting to see this robot struggle | 0:50:30 | 0:50:33 | |

with an environment and learn, which is the most striking thing. | 0:50:33 | 0:50:36 | |

Well, exactly. Deconstructing the things that we take | 0:50:36 | 0:50:39 | |

completely for granted is actually very, very hard to do | 0:50:39 | 0:50:42 | |

and the best way they've found is to let it make mistakes. | 0:50:42 | 0:50:45 | |

Fall over, try things out and the world is built for us, | 0:50:45 | 0:50:49 | |

two arms, two legs, and it has to sort of replace that functionality. | 0:50:49 | 0:50:54 | |

This ability to check different textures, | 0:50:54 | 0:50:56 | |

I mean, this would be particularly useful | 0:50:56 | 0:50:58 | |

if we were going to send them off into space to do mining or | 0:50:58 | 0:51:01 | |

exploration, the ability to basically touch different surfaces. | 0:51:01 | 0:51:06 | |

Exactly. Touch is so essential to how we get feedback. | 0:51:06 | 0:51:10 | |

That's the weakness of robotics today. | 0:51:10 | 0:51:12 | |

Robotics is a massive investment in the future? | 0:51:12 | 0:51:15 | |

Japan makes 30% of all robots, and remember in the Shinto religion, | 0:51:15 | 0:51:19 | |

people believe that there are spirits even in robots. | 0:51:19 | 0:51:21 | |

That's why children love robots in Japan. | 0:51:21 | 0:51:24 | |

There are plays in Japan where robots actually play | 0:51:24 | 0:51:28 | |

a certain person in the play and robots greet you at grocery stores, | 0:51:28 | 0:51:33 | |

inside convenience stores, because of this Shinto tradition | 0:51:33 | 0:51:36 | |

that you believe there are spirits everywhere. | 0:51:36 | 0:51:38 | |

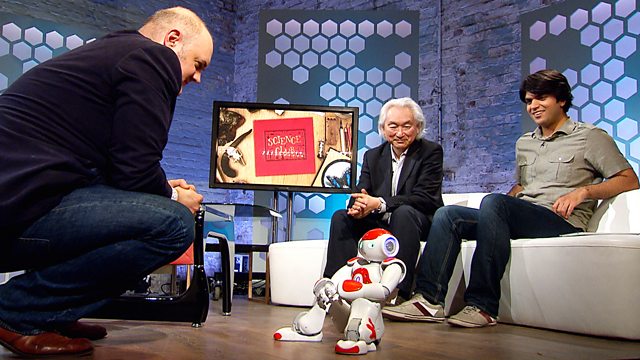

OK, now I'm going to introduce you to a robot here. | 0:51:38 | 0:51:41 | |

This is a little fellow called NAO. | 0:51:41 | 0:51:43 | |

NAO lives in a school in Birmingham where | 0:51:43 | 0:51:45 | |

he works with some autistic children there. | 0:51:45 | 0:51:47 | |

Now, let's see if I've got these controls right. | 0:51:47 | 0:51:49 | |

Don't keep moving your head, all right? | 0:51:49 | 0:51:52 | |

Launch a task. | 0:51:53 | 0:51:55 | |

-NAO: -Which task do you want to launch? | 0:51:55 | 0:51:58 | |

Presentation. | 0:51:58 | 0:51:59 | |

Presentation. | 0:51:59 | 0:52:00 | |

Hello, my name is NAO. | 0:52:11 | 0:52:13 | |

I'm a humanoid robot, imagined and manufactured by Aldebaran Robotics. | 0:52:15 | 0:52:21 | |

I come with software and I'm fully programmable. | 0:52:21 | 0:52:25 | |

I'm autonomous and I can connect to the internet through Wi-Fi. | 0:52:27 | 0:52:31 | |

LAUGHTER | 0:52:31 | 0:52:33 | |

I can recognise your face, answer your questions, | 0:52:33 | 0:52:37 | |

play music, grab objects and even play soccer like a pro. | 0:52:37 | 0:52:44 | |

LAUGHTER | 0:52:44 | 0:52:47 | |

-Do you want more technical details? -No. | 0:52:47 | 0:52:51 | |

There we go. You can sit down again, NAO. | 0:52:54 | 0:52:57 | |

Oh, how sweet is that? That's gorgeous. That's NAO. | 0:53:04 | 0:53:07 | |

APPLAUSE | 0:53:07 | 0:53:09 | |

So, in a school outside Birmingham, there are 15 autistic students | 0:53:13 | 0:53:16 | |

and they work with NAO all the time. | 0:53:16 | 0:53:19 | |

I mean, we can see robots being useful in that | 0:53:19 | 0:53:21 | |

-kind of therapeutic environment as well? -Yeah, absolutely. | 0:53:21 | 0:53:24 | |

I mean, what's amazing is how quickly | 0:53:24 | 0:53:26 | |

and automatically we attribute a mind and emotions to... | 0:53:26 | 0:53:30 | |

It's an object. | 0:53:30 | 0:53:32 | |

As far as I know, it doesn't actually feel pain or anything | 0:53:32 | 0:53:35 | |

but it's just amazing how automatically we have these | 0:53:35 | 0:53:38 | |

feelings about something that behaves even remotely like a human. | 0:53:38 | 0:53:42 | |

One of the things that advanced Graspy and Hubo was the DARPA prize. | 0:53:42 | 0:53:47 | |

-Yeah. -It's in the grand tradition. | 0:53:47 | 0:53:50 | |

There's a long tradition of prizes, | 0:53:50 | 0:53:51 | |