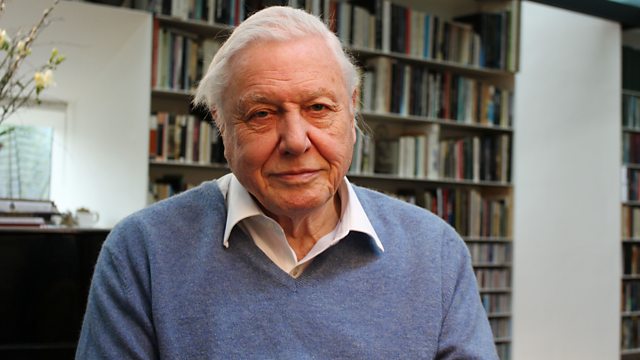

Episode 7 David Attenborough's Natural Curiosities

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Episode 7. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

The natural world is full of extraordinary animals | 0:00:02 | 0:00:06 | |

with amazing life histories. | 0:00:06 | 0:00:09 | |

Yet certain stories are more intriguing than most. | 0:00:09 | 0:00:13 | |

The mysteries of a butterfly's life cycle | 0:00:16 | 0:00:19 | |

or the strange biology of the Emperor penguin. | 0:00:19 | 0:00:23 | |

Some of these creatures were surrounded by myth | 0:00:23 | 0:00:26 | |

and misunderstandings for a very long time | 0:00:26 | 0:00:30 | |

and some have only recently revealed their secrets. | 0:00:30 | 0:00:33 | |

These are the animals that stand out from the crowd. | 0:00:35 | 0:00:39 | |

The curiosities I find most fascinating of all. | 0:00:39 | 0:00:42 | |

Some animals appear to protect themselves | 0:00:51 | 0:00:54 | |

with formidable suits of armour. | 0:00:54 | 0:00:57 | |

The rhino carries plates of thick hide on its flanks. | 0:00:57 | 0:01:00 | |

While the hedgehog is covered in prickly spines. | 0:01:02 | 0:01:06 | |

Both, in previous centuries, | 0:01:07 | 0:01:09 | |

inspired far-fetched and outlandish ideas, | 0:01:09 | 0:01:14 | |

but what is the true nature of their strange coats? | 0:01:14 | 0:01:18 | |

Some animals have mastered the art of deception. | 0:01:25 | 0:01:29 | |

The cuckoo tricks other birds into raising its young, | 0:01:29 | 0:01:34 | |

while the death's-head hawkmoth infiltrates the nests of bees | 0:01:34 | 0:01:38 | |

to steal their precious honey. | 0:01:38 | 0:01:41 | |

They're cheats and impostors. | 0:01:42 | 0:01:45 | |

Rhinoceroses are strange-looking creatures. | 0:01:55 | 0:01:58 | |

There are five kinds. | 0:01:58 | 0:02:00 | |

The Indian, this one, has a single horn, squat legs, tiny eyes... | 0:02:00 | 0:02:05 | |

Whoa! | 0:02:05 | 0:02:07 | |

..and thick folded skin. | 0:02:07 | 0:02:10 | |

For many centuries, before any had reached Europe, | 0:02:10 | 0:02:13 | |

they were surrounded by myth as much as the unicorn. | 0:02:13 | 0:02:17 | |

Few people had ever seen a live rhino, but, in 1741, | 0:02:17 | 0:02:22 | |

a young Indian rhinoceros called Clara came to Europe | 0:02:22 | 0:02:26 | |

and she transformed our image and understanding of the rhinoceros. | 0:02:26 | 0:02:30 | |

Thank you. | 0:02:31 | 0:02:33 | |

Before Clara arrived, | 0:02:34 | 0:02:36 | |

little was known in Europe about the rhinoceros. | 0:02:36 | 0:02:39 | |

A few animals arrived here in Roman times, but they didn't last long, | 0:02:39 | 0:02:44 | |

many being slaughtered during the brutal Roman Games. | 0:02:44 | 0:02:47 | |

It wasn't until the 16th century | 0:02:48 | 0:02:50 | |

that they first made a real mark on western society. | 0:02:50 | 0:02:54 | |

In 1515, a woodcut of a rhino was created by an artist called Durer. | 0:02:56 | 0:03:00 | |

It was a beautiful image of an elaborately armoured creature, | 0:03:02 | 0:03:06 | |

but it was inaccurate. | 0:03:06 | 0:03:09 | |

It's doubtful whether Durer ever saw a live rhinoceros. | 0:03:09 | 0:03:13 | |

It's little wonder that the rhinoceros was thought of | 0:03:15 | 0:03:19 | |

as a magical mythical creature | 0:03:19 | 0:03:21 | |

if Durer's woodcut of 1515 was to be believed. | 0:03:21 | 0:03:25 | |

He shows an armour-plated beast with a large horn | 0:03:25 | 0:03:29 | |

and a strange little spike on its back. | 0:03:29 | 0:03:32 | |

But in the 18th century, the perception of the rhinoceros was | 0:03:32 | 0:03:35 | |

to change when Clara came to Europe on an extraordinary 17-year tour. | 0:03:35 | 0:03:41 | |

Clara was captured in Assam at just a few months of age | 0:03:43 | 0:03:46 | |

when hunters killed her mother. | 0:03:46 | 0:03:48 | |

A director of the Dutch East India Company | 0:03:48 | 0:03:50 | |

raised her in his household as a pet. | 0:03:50 | 0:03:53 | |

She wandered indoors amongst the elegant furniture, | 0:03:53 | 0:03:56 | |

ate from a plate and was a popular attraction at his dinner parties. | 0:03:56 | 0:03:59 | |

But, inevitably, Clara got too big | 0:03:59 | 0:04:03 | |

and a little-known Dutch sea captain called Van der Meer | 0:04:03 | 0:04:06 | |

seized the chance to own possibly the only tame rhino in the world. | 0:04:06 | 0:04:11 | |

He saw the opportunity of making a lifetime's income | 0:04:11 | 0:04:14 | |

with an ambitious rhinoceros tour. | 0:04:14 | 0:04:17 | |

Clara became an orphan while she was still dependent on her mother. | 0:04:20 | 0:04:24 | |

Rhino calves usually stay with their mothers for up to two years, | 0:04:24 | 0:04:29 | |

sustained by the milk. | 0:04:29 | 0:04:31 | |

Only after that are they able to feed independently | 0:04:31 | 0:04:34 | |

on soft green grass. | 0:04:34 | 0:04:36 | |

Keeping a young rhino healthy was certainly a challenge, | 0:04:38 | 0:04:41 | |

but Van der Meer was smart and took good care of his new charge. | 0:04:41 | 0:04:46 | |

He travelled with her all the way from India | 0:04:48 | 0:04:50 | |

around the Cape of Good Hope, up the coast of Africa to the Netherlands | 0:04:50 | 0:04:54 | |

and his home town of Leiden. | 0:04:54 | 0:04:57 | |

He discovered very soon that Clara had a huge appetite | 0:04:57 | 0:05:01 | |

and he made sure that she always had plenty to eat. | 0:05:01 | 0:05:04 | |

Rhinoceros spend a great deal of time feeding. | 0:05:05 | 0:05:10 | |

They eat plant matter, but they don't have multiple stomachs | 0:05:10 | 0:05:13 | |

to digest and absorb nutrients, | 0:05:13 | 0:05:15 | |

so they need to eat large quantities of food to survive, | 0:05:15 | 0:05:18 | |

up to 100 kilos a day. | 0:05:18 | 0:05:20 | |

It takes a lot to fuel such an enormous body. | 0:05:23 | 0:05:27 | |

An adult rhino weighs over a tonne. | 0:05:27 | 0:05:29 | |

And the Indian rhino has a special mobile lip | 0:05:31 | 0:05:33 | |

to help it grasp and rip up the vegetation. | 0:05:33 | 0:05:37 | |

After reaching Europe, Clara lived quietly in Leiden for two years, | 0:05:42 | 0:05:46 | |

feeding and growing, | 0:05:46 | 0:05:48 | |

while Van der Meer made plans for his European tour. | 0:05:48 | 0:05:52 | |

At the time, a live rhino was a wondrous thing, | 0:05:53 | 0:05:57 | |

as Van der Meer well appreciated. | 0:05:57 | 0:06:00 | |

He was a clever businessman and he knew that publicity was needed | 0:06:00 | 0:06:04 | |

if his grand tour was to be a success. | 0:06:04 | 0:06:07 | |

Van der Meer made an unusual alliance with an ambitious | 0:06:09 | 0:06:12 | |

Dutch anatomist, BS Albinus, | 0:06:12 | 0:06:15 | |

who was hoping to produce a definitive medical textbook. | 0:06:15 | 0:06:19 | |

Both men were looking for publicity | 0:06:19 | 0:06:21 | |

and together they commissioned Jan Wandelaar, | 0:06:21 | 0:06:24 | |

an accomplished artist, | 0:06:24 | 0:06:25 | |

to make prints that would serve to advertise both the book and Clara. | 0:06:25 | 0:06:30 | |

They were strange but compelling pictures that combined | 0:06:30 | 0:06:33 | |

precisely drawn human skeletons and detailed images of Clara. | 0:06:33 | 0:06:39 | |

They were the most accurate drawings yet of the rhinoceros. | 0:06:39 | 0:06:43 | |

Wandelaar sketched Clara from life. | 0:06:44 | 0:06:46 | |

He was fascinated by the texture of her skin | 0:06:46 | 0:06:50 | |

and he depicted a rhino more realistically than Durer did , | 0:06:50 | 0:06:54 | |

so, at last, | 0:06:54 | 0:06:55 | |

the myths surrounding the animal's appearance came to an end. | 0:06:55 | 0:06:58 | |

As the news of Clara's tour spread, | 0:07:00 | 0:07:03 | |

everyone was eager to see this wonderful new creature | 0:07:03 | 0:07:06 | |

and Clara's first trip to Vienna was for a royal appointment. | 0:07:06 | 0:07:10 | |

The Empress Maria-Theresa was so eager to see Clara | 0:07:12 | 0:07:15 | |

and so impressed by her appearance and good temperament, | 0:07:15 | 0:07:18 | |

that she brought her children back for another private showing. | 0:07:18 | 0:07:22 | |

Clara became the talk of the town | 0:07:22 | 0:07:25 | |

and European heads of state were eager to meet her. | 0:07:25 | 0:07:28 | |

She travelled through Europe like a celebrity | 0:07:31 | 0:07:33 | |

and met both royalty and crowds of curious onlookers. | 0:07:33 | 0:07:38 | |

Her horn in particular attracted much attention. | 0:07:39 | 0:07:43 | |

In Paris she started a rhino-mania | 0:07:43 | 0:07:46 | |

with fashionable women styling their hair 'a-la rhinoceros!' | 0:07:46 | 0:07:51 | |

Some regarded rhinos as living unicorns. | 0:07:57 | 0:08:00 | |

The scientific name for the Indian rhino is, in fact, | 0:08:00 | 0:08:03 | |

Rhinoceros Unicornis, | 0:08:03 | 0:08:06 | |

and, at the time, it was believed that the horn was made of bone. | 0:08:06 | 0:08:11 | |

But this in fact is not the case. | 0:08:11 | 0:08:14 | |

Rhinoceros horn grows from a spongy base positioned here on the skull. | 0:08:17 | 0:08:23 | |

The horn has no bony core. | 0:08:23 | 0:08:26 | |

It's made of keratin, the same substance as fingernails | 0:08:26 | 0:08:29 | |

and can grow again if it's lost. | 0:08:29 | 0:08:32 | |

Well, in June 1750, Clara's horn fell off, | 0:08:32 | 0:08:36 | |

probably due to her rubbing it on the travel crate. | 0:08:36 | 0:08:39 | |

To Van der Meer, this seemed to be a disaster | 0:08:39 | 0:08:42 | |

since he had no idea that it would regrow. | 0:08:42 | 0:08:45 | |

But, ingenuously, he used the event as a publicity stunt and the crowds | 0:08:45 | 0:08:48 | |

flocked all the more to see Clara fearing that she might be dying. | 0:08:48 | 0:08:52 | |

Even without a horn, Clara was still a fascinating creature | 0:08:56 | 0:08:59 | |

and her strange armoured skin was another talking point. | 0:08:59 | 0:09:03 | |

Why would such a gentle creature have such thick and elaborate folds? | 0:09:03 | 0:09:08 | |

The rhinoceros's skin in some parts is almost five centimetres thick, | 0:09:10 | 0:09:15 | |

nearly three times thicker than you would expect | 0:09:15 | 0:09:18 | |

for an animal that size. | 0:09:18 | 0:09:20 | |

We now know that, in the wild, | 0:09:23 | 0:09:25 | |

rhinoceros are not always as gentle as Clara. | 0:09:25 | 0:09:28 | |

They can be very aggressive, | 0:09:28 | 0:09:30 | |

particularly during the mating season, | 0:09:30 | 0:09:32 | |

and the tough skin provides them with some protection. | 0:09:32 | 0:09:36 | |

But it also has other benefits. | 0:09:36 | 0:09:39 | |

Thick skin is a good barrier against sun, flies and other parasites, | 0:09:39 | 0:09:45 | |

but why the skin of an Indian rhino grows in plate-like structures | 0:09:45 | 0:09:49 | |

with deep grooves has only recently been explained. | 0:09:49 | 0:09:54 | |

We know that the thicker skin areas are good physical protection, | 0:09:54 | 0:09:57 | |

but something deeper is going on. | 0:09:57 | 0:09:59 | |

It seems that the large folds increase the surface area | 0:10:01 | 0:10:05 | |

of the skin and help the rhino regulate its body temperature. | 0:10:05 | 0:10:10 | |

The tissues around the grooves are particularly rich in blood vessels | 0:10:10 | 0:10:14 | |

and transmit heat to the enlarged skin plates | 0:10:14 | 0:10:17 | |

which act like cooling radiators. | 0:10:17 | 0:10:20 | |

Indian rhinoceros bathe regularly and the folds in their skin | 0:10:22 | 0:10:26 | |

not only trap water but hold it even after they come back onto land. | 0:10:26 | 0:10:31 | |

So it turns out that the Indian rhinoceros's skin | 0:10:33 | 0:10:36 | |

is a far more specialised structure than anyone could have imagined. | 0:10:36 | 0:10:40 | |

For 17 years, Clara travelled across Europe, | 0:10:43 | 0:10:47 | |

stopping off in all the main towns and cities. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:50 | |

Everywhere she went, the crowds queued up to see her. | 0:10:50 | 0:10:53 | |

She visited England three times, | 0:10:55 | 0:10:58 | |

but her third visit proved to be her last. | 0:10:58 | 0:11:01 | |

In 1758, at the age of little more than 20, | 0:11:03 | 0:11:07 | |

Clara unexpectedly died in London. | 0:11:07 | 0:11:11 | |

Van der Meer was deeply shocked as he thought she might live to be 100. | 0:11:11 | 0:11:15 | |

Life on the road was over, but Clara's 17-year tour | 0:11:15 | 0:11:20 | |

had changed the image of the rhinoceros forever. | 0:11:20 | 0:11:24 | |

Durer's classic engraving of the fierce armoured beast was now | 0:11:24 | 0:11:27 | |

a part of history and new accurate images were produced. | 0:11:27 | 0:11:32 | |

The true Indian rhinoceros, like Clara, | 0:11:32 | 0:11:35 | |

looked just like this wonderful animal | 0:11:35 | 0:11:37 | |

painted by the great 18th-century artist George Stubbs. | 0:11:37 | 0:11:41 | |

Van der Meer made his fortune with her on the grand tour, | 0:11:44 | 0:11:47 | |

but Clara, more importantly, also enabled people | 0:11:47 | 0:11:50 | |

to get a first realistic view of what a rhinoceros looks like | 0:11:50 | 0:11:54 | |

and put to rest the idea of a heavily armoured mythical creature. | 0:11:54 | 0:11:59 | |

There is a more familiar animal whose body armour | 0:12:04 | 0:12:08 | |

also perplexed us for a surprisingly long time. | 0:12:08 | 0:12:11 | |

The hedgehog. | 0:12:11 | 0:12:14 | |

This delightful little creature is one of our most familiar | 0:12:14 | 0:12:18 | |

garden animals and yet it's got a surprisingly unusual appearance. | 0:12:18 | 0:12:23 | |

Instead of fur, like most mammals, it's got a thick coat of spines. | 0:12:23 | 0:12:28 | |

The only part of its body not covered by them | 0:12:28 | 0:12:31 | |

are its face and its underside. | 0:12:31 | 0:12:33 | |

The hedgehog's coat may appear to be painfully prickly, | 0:12:33 | 0:12:37 | |

but when the hedgehog is relaxed, it can lay its spines down flat. | 0:12:37 | 0:12:41 | |

When it senses danger, of course, it rolls itself up into a ball | 0:12:41 | 0:12:45 | |

and is completely hidden and protected. | 0:12:45 | 0:12:48 | |

It's a formidable suit of armour, these spines. | 0:12:48 | 0:12:50 | |

Nothing much can get past them. | 0:12:50 | 0:12:53 | |

It seems obvious that spines must serve as a protection | 0:12:53 | 0:12:58 | |

but their function was, in fact, misunderstood for a long time. | 0:12:58 | 0:13:02 | |

Early books claimed the spines were used for collecting food. | 0:13:04 | 0:13:08 | |

The hedgehogs were said to climb apple trees, | 0:13:08 | 0:13:11 | |

knock down the fruit and roll on it, impaling the apples on their spines | 0:13:11 | 0:13:15 | |

and carrying them off to their burrows. | 0:13:15 | 0:13:18 | |

Today we know that hedgehogs are better at climbing | 0:13:22 | 0:13:25 | |

than you might think, but they still haven't been seen to climb trees. | 0:13:25 | 0:13:29 | |

And there were other myths. | 0:13:34 | 0:13:36 | |

In medieval times, farmers believed that hedgehogs would steal milk | 0:13:36 | 0:13:40 | |

from their cows at night. | 0:13:40 | 0:13:42 | |

So the Elizabethan Parliament put a three-pence bounty on the head | 0:13:42 | 0:13:47 | |

of every hedgehog and thousands were slaughtered as a result. | 0:13:47 | 0:13:51 | |

Our attitude to the hedgehog is now very different. | 0:13:53 | 0:13:57 | |

Today, many of us get great pleasure | 0:14:01 | 0:14:03 | |

from seeing this appealing little creature in our gardens. | 0:14:03 | 0:14:08 | |

We know that they are a gardener's friend, | 0:14:08 | 0:14:10 | |

feeding mostly on insects and slugs | 0:14:10 | 0:14:12 | |

and helping to rid our plants of pests. | 0:14:12 | 0:14:15 | |

Some of us even put out special food to attract them. | 0:14:15 | 0:14:18 | |

We now also understand more about the hedgehog's spines. | 0:14:20 | 0:14:25 | |

They are, in fact, modified hairs, | 0:14:25 | 0:14:28 | |

hollow inside but reinforced with keratin, | 0:14:28 | 0:14:31 | |

the same material that forms a rhinoceros's horn. | 0:14:31 | 0:14:34 | |

That makes them strong while keeping weight down to a minimum. | 0:14:36 | 0:14:40 | |

A hedgehog has over 5,000 spines | 0:14:41 | 0:14:45 | |

and their main purpose is indeed protection. | 0:14:45 | 0:14:49 | |

But hedgehogs don't start life with a coat of armour. | 0:14:51 | 0:14:55 | |

It would be painful for a hedgehog mother | 0:15:01 | 0:15:04 | |

to give birth to spiny babies. | 0:15:04 | 0:15:06 | |

But nature has dealt with that problem. | 0:15:06 | 0:15:09 | |

Tiny hoglets are born with their spines covered by a layer of skin. | 0:15:09 | 0:15:14 | |

Within a few hours, the thin quills break through. | 0:15:17 | 0:15:20 | |

A baby hedgehog's first spines are soft and white | 0:15:23 | 0:15:27 | |

but these soon fall out and are replaced by darker and harder ones. | 0:15:27 | 0:15:31 | |

Hedgehog spines are shed and regrown at various stages in their lives, | 0:15:40 | 0:15:44 | |

just like the hair of mammals. | 0:15:44 | 0:15:46 | |

Surprisingly, a spiny armour is not common in the animal kingdom. | 0:15:51 | 0:15:55 | |

In Europe, the hedgehog is the only one of its kind. | 0:15:57 | 0:16:01 | |

But in other parts of the world, there are creatures that have | 0:16:03 | 0:16:06 | |

evolved a similar spiky coat. | 0:16:06 | 0:16:08 | |

This is an African crested porcupine. | 0:16:15 | 0:16:17 | |

It's got a formidable coat of spines but it's no relative | 0:16:18 | 0:16:22 | |

of the hedgehog and the spines are in fact very different. | 0:16:22 | 0:16:26 | |

For one thing, they are very much longer. | 0:16:26 | 0:16:30 | |

Normally, they lie flat against the body but if the animal is irritated, | 0:16:30 | 0:16:34 | |

it directs them to give a very spectacular warning. | 0:16:34 | 0:16:37 | |

Even the most ferocious predator will take care | 0:16:39 | 0:16:42 | |

when approaching a porcupine. | 0:16:42 | 0:16:44 | |

The quills will break off easily and become lodged in the skin. | 0:16:46 | 0:16:49 | |

The lion's only chance is to attack from the front. | 0:16:52 | 0:16:55 | |

As they circle, the porcupine twists and turns | 0:16:58 | 0:17:01 | |

to keep its armoured back to them. | 0:17:01 | 0:17:03 | |

This time, the lion got too close. | 0:17:07 | 0:17:10 | |

It has no way of removing the spike and may be unable to feed. | 0:17:12 | 0:17:16 | |

It could prove fatal for the predator. | 0:17:17 | 0:17:19 | |

Although the porcupine's quills may appear thin, even flimsy, | 0:17:24 | 0:17:28 | |

once they get stuck in your flesh, they are remarkably difficult | 0:17:28 | 0:17:32 | |

and painful to remove. | 0:17:32 | 0:17:34 | |

Why this should be was not known until recently. | 0:17:34 | 0:17:37 | |

But when looked at under an electron microscope, you can see | 0:17:37 | 0:17:41 | |

that each quill is coated with tiny backwards facing barbs. | 0:17:41 | 0:17:45 | |

The barbs act like the teeth on a serrated knife, | 0:17:46 | 0:17:49 | |

making it easier to penetrate the skin, | 0:17:49 | 0:17:51 | |

but when it comes to removing the quills, | 0:17:51 | 0:17:54 | |

the barbs have the opposite effect and act as anchors, | 0:17:54 | 0:17:57 | |

preventing the spine from sliding out of the wound. | 0:17:57 | 0:18:00 | |

The porcupine's spiky coat seems more formidable than the hedgehog's. | 0:18:03 | 0:18:09 | |

But the hedgehog has a very effective way of protecting | 0:18:09 | 0:18:13 | |

its vulnerable underbelly. | 0:18:13 | 0:18:16 | |

It rolls itself into a ball, so that it is completely encased in spines. | 0:18:16 | 0:18:22 | |

Foxes do attack hedgehogs but a fox must wait until the animal | 0:18:26 | 0:18:30 | |

is on the move if it is to get at its unprotected underside. | 0:18:30 | 0:18:34 | |

If the hedgehog stays rolled in a defensive ball, | 0:18:37 | 0:18:40 | |

the fox can't harm it. | 0:18:40 | 0:18:42 | |

All the hedgehog has to do is to sit it out until the fox loses interest. | 0:18:45 | 0:18:51 | |

But if spines are such an effective defence, | 0:18:59 | 0:19:02 | |

why don't many other animals adopt them? | 0:19:02 | 0:19:05 | |

The answer seems to be connected with the difficulties | 0:19:05 | 0:19:09 | |

of life with spines. | 0:19:09 | 0:19:11 | |

Spines may be something of a hindrance when it comes to mating. | 0:19:13 | 0:19:17 | |

Indeed, early naturalists thought that the hedgehogs must mate | 0:19:19 | 0:19:23 | |

belly to belly to avoid being impaled on each other's spines. | 0:19:23 | 0:19:27 | |

We now know that that's not the case. | 0:19:29 | 0:19:31 | |

The spines seem to do nothing | 0:19:31 | 0:19:33 | |

to hinder the ardour of a male hedgehog. | 0:19:33 | 0:19:37 | |

If she is willing, he tries to oblige. | 0:19:37 | 0:19:41 | |

But it still looks like a tricky and uncomfortable operation. | 0:19:41 | 0:19:46 | |

Despite the limitations of a spiny coat, | 0:19:53 | 0:19:56 | |

hedgehogs have remained largely unchanged | 0:19:56 | 0:19:59 | |

for almost 15 million years. | 0:19:59 | 0:20:03 | |

New evidence suggests that the spines may play another | 0:20:03 | 0:20:06 | |

rather surprising role in their lives. | 0:20:06 | 0:20:09 | |

Hedgehogs, when encountering an unfamiliar or toxic object, | 0:20:12 | 0:20:16 | |

sometimes behave in a very strange way. | 0:20:16 | 0:20:21 | |

They will lick and bite it until they start to foam at the mouth. | 0:20:21 | 0:20:25 | |

The froth is then transferred to their spines. | 0:20:25 | 0:20:29 | |

We still don't fully understand this strange behaviour. | 0:20:30 | 0:20:34 | |

It may help to camouflage the hedgehog's smell, | 0:20:35 | 0:20:39 | |

or make the spiny coat more distasteful to predators. | 0:20:39 | 0:20:42 | |

Or maybe it helps hedgehogs communicate with each other. | 0:20:46 | 0:20:50 | |

Or make them more attractive to the opposite sex. | 0:20:50 | 0:20:53 | |

We might one day discover its true purpose but we haven't yet. | 0:20:54 | 0:20:59 | |

Our familiar British hedgehog has provoked some very strange | 0:21:05 | 0:21:10 | |

and far-fetched ideas, but, for many of us, | 0:21:10 | 0:21:13 | |

it remains one of the most engaging animals in the British countryside, | 0:21:13 | 0:21:17 | |

and its prickly coat makes it that much more attractive. | 0:21:17 | 0:21:21 | |

So, it turns out that some of the early ideas about the purpose | 0:21:24 | 0:21:28 | |

of the rhino's armour and the hedgehog's spines | 0:21:28 | 0:21:30 | |

were only partly correct. | 0:21:30 | 0:21:33 | |

Their true functions are far more complex than we yet realise. | 0:21:33 | 0:21:38 | |

CUCKOO CALLS | 0:21:46 | 0:21:50 | |

The call of the cuckoo has long been regarded as a sign of spring. | 0:21:50 | 0:21:55 | |

But, in fact, it's the call of a killer and a cheat. | 0:21:55 | 0:21:59 | |

The cuckoo lays its egg in the nests of other birds and somehow | 0:21:59 | 0:22:03 | |

persuades them to treat it and its chick as if it were their own. | 0:22:03 | 0:22:08 | |

How does it get away with it? | 0:22:08 | 0:22:10 | |

It's a question that has puzzled people for centuries. | 0:22:10 | 0:22:14 | |

In Britain, the cuckoo arrives at a time | 0:22:15 | 0:22:18 | |

when most birds are nesting and laying eggs. | 0:22:18 | 0:22:21 | |

Early egg collectors noticed that the nests of some birds | 0:22:21 | 0:22:26 | |

had a slightly odd-looking egg in them. | 0:22:26 | 0:22:29 | |

These are the eggs laid by a number of different birds. | 0:22:29 | 0:22:32 | |

A marsh warbler, spotted flycatcher, a linnet and a whitethroat. | 0:22:32 | 0:22:38 | |

Amongst each of those clutches, there is a fraudster, a cuckoo egg, | 0:22:38 | 0:22:43 | |

which mimics that of its host. | 0:22:43 | 0:22:45 | |

Although cuckoos are long known to lay their eggs in the nests | 0:22:48 | 0:22:51 | |

of other birds, no-one had actually described it happening. | 0:22:51 | 0:22:55 | |

Then, in the 18th century, an English country doctor | 0:22:56 | 0:23:00 | |

with an interest in natural history decided to investigate. | 0:23:00 | 0:23:04 | |

Edward Jenner lived here in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, | 0:23:06 | 0:23:10 | |

and is best known for his work on the smallpox vaccine. | 0:23:10 | 0:23:15 | |

In fact, he is said to be the father of vaccination and that | 0:23:15 | 0:23:18 | |

his work has saved more human lives than that of any other man. | 0:23:18 | 0:23:23 | |

What is less known is that he first achieved scientific distinction | 0:23:23 | 0:23:28 | |

by his observations on the behaviour of the cuckoo. | 0:23:28 | 0:23:31 | |

At the time, it was believed that a cuckoo removes | 0:23:35 | 0:23:38 | |

all of the eggs in a nest and then lays its own. | 0:23:38 | 0:23:41 | |

By doing so, it would ensure its own chick gets all the food | 0:23:43 | 0:23:46 | |

brought in by the unwitting nest owners. | 0:23:46 | 0:23:49 | |

But Edward Jenner's detailed observations were to reveal | 0:23:51 | 0:23:55 | |

a rather darker tale. | 0:23:55 | 0:23:57 | |

Jenner's work on cuckoos was published in 1788 | 0:23:59 | 0:24:03 | |

here in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, | 0:24:03 | 0:24:07 | |

the world's first scientific society. | 0:24:07 | 0:24:10 | |

It was entitled simply... | 0:24:10 | 0:24:12 | |

"Observations on the natural history of the cuckoo" | 0:24:12 | 0:24:15 | |

by Mr Edward Jenner. | 0:24:15 | 0:24:17 | |

In it, he reported that it was not the parent cuckoo | 0:24:17 | 0:24:21 | |

but the newly hatched chick which pushes the eggs | 0:24:21 | 0:24:23 | |

and nestlings of the foster parents out of the nest. | 0:24:23 | 0:24:26 | |

As soon as it hatches, | 0:24:27 | 0:24:29 | |

the cuckoo chick's instinct is to kill anything else in the nest. | 0:24:29 | 0:24:34 | |

It's still blind and naked | 0:24:34 | 0:24:36 | |

but it has a cup-shaped depression on its back | 0:24:36 | 0:24:39 | |

into which an egg fits perfectly. | 0:24:39 | 0:24:41 | |

But sometimes the other eggs hatch earlier and Jenner's observations | 0:24:43 | 0:24:49 | |

of how the cuckoo chick deals with its nest mates | 0:24:49 | 0:24:51 | |

were quite shocking. | 0:24:51 | 0:24:53 | |

He writes... | 0:24:55 | 0:24:56 | |

"the moment of accomplishing this was very curious. | 0:24:56 | 0:24:59 | |

"The little animal, with the assistance of its rump and wings, | 0:24:59 | 0:25:03 | |

"contrived to get the bird on its back | 0:25:03 | 0:25:05 | |

"and, making a lodgement of the burden by elevating its elbows, | 0:25:05 | 0:25:09 | |

"clambered backwards with it up the side of the nest | 0:25:09 | 0:25:12 | |

"until it reached the top, where, resting for a moment, | 0:25:12 | 0:25:15 | |

"it threw off its load with a jerk | 0:25:15 | 0:25:18 | |

"and quite disengaged it from the nest." | 0:25:18 | 0:25:22 | |

The real villain had been uncovered. | 0:25:22 | 0:25:25 | |

Jenner's views were met with incredulity and some disbelief, | 0:25:25 | 0:25:29 | |

but nonetheless they earned him the Fellowship of the Royal Society. | 0:25:29 | 0:25:33 | |

It was the greatest honour that could be given to | 0:25:33 | 0:25:35 | |

a scientist at the time. | 0:25:35 | 0:25:37 | |

Jenner's observations had revealed | 0:25:38 | 0:25:40 | |

the true nature of the cuckoo's deception. | 0:25:40 | 0:25:44 | |

But it still wasn't clear why the cuckoos should opt for this | 0:25:44 | 0:25:47 | |

strange way of raising its young. | 0:25:47 | 0:25:50 | |

It wasn't until 100 years later that Charles Darwin finally | 0:25:53 | 0:25:57 | |

provided an explanation with his theory of evolution. | 0:25:57 | 0:26:01 | |

The cuckoo's behaviour has evolved | 0:26:02 | 0:26:04 | |

to increase its own breeding success. | 0:26:04 | 0:26:07 | |

By avoiding the task of raising chicks, | 0:26:07 | 0:26:09 | |

the cuckoo can lay more eggs than any other bird, | 0:26:09 | 0:26:13 | |

as many as 25 in a season. | 0:26:13 | 0:26:16 | |

While it makes evolutionary sense for the cuckoo | 0:26:19 | 0:26:22 | |

to lay its eggs in the nests of others, what about its victims? | 0:26:22 | 0:26:25 | |

Why do they put up with this trickery? | 0:26:25 | 0:26:28 | |

It seems that they sometimes don't. | 0:26:28 | 0:26:31 | |

This was revealed in an early natural history film in 1920. | 0:26:32 | 0:26:36 | |

The Cuckoo's Secret was made by Edgar Chance and Oliver Pike, | 0:26:38 | 0:26:42 | |

an egg collector and a wildlife film maker. | 0:26:42 | 0:26:46 | |

Chance was fascinated by cuckoos | 0:26:46 | 0:26:49 | |

and spent a great deal of time following them. | 0:26:49 | 0:26:51 | |

He was the first person known to see a cuckoo lay its egg. | 0:26:51 | 0:26:55 | |

The deception involves stealth and speed. | 0:26:57 | 0:27:02 | |

The female waits until a nest is unattended and then she strikes. | 0:27:02 | 0:27:06 | |

But if she is spotted, the owners fight back. | 0:27:06 | 0:27:09 | |

If she is successful, | 0:27:10 | 0:27:12 | |

the whole deception takes less than ten seconds. | 0:27:12 | 0:27:16 | |

She removes and eats just one egg and replaces it with her own. | 0:27:16 | 0:27:20 | |

The Chance and Pike film solved one mystery, | 0:27:25 | 0:27:28 | |

but there were still others. | 0:27:28 | 0:27:30 | |

How does the cuckoo choose its victim? | 0:27:31 | 0:27:33 | |

And why don't the nest owners reject the alien egg? | 0:27:34 | 0:27:38 | |

Reed warblers are one of the cuckoo's main targets | 0:27:47 | 0:27:50 | |

and the pair has a nest just in here. | 0:27:50 | 0:27:53 | |

The female warbler has laid four speckled eggs, | 0:27:58 | 0:28:01 | |

and, using a model egg, I can illustrate the cuckoo's trickery. | 0:28:01 | 0:28:05 | |

This is the sort of egg that a cuckoo would lay | 0:28:07 | 0:28:10 | |

in the reed warbler's nest. | 0:28:10 | 0:28:12 | |

It matches the reed warbler's actual egg very closely in colour. | 0:28:13 | 0:28:18 | |

Experiments with model eggs have shown that reed warblers | 0:28:20 | 0:28:24 | |

have become very good at recognising an alien egg | 0:28:24 | 0:28:27 | |

and either throw it out or desert their nest to start afresh. | 0:28:27 | 0:28:32 | |

So the cuckoo has to make sure that it produces an egg | 0:28:32 | 0:28:36 | |

that is a very good match. | 0:28:36 | 0:28:37 | |

The cuckoo and its victims are evolving competitively. | 0:28:41 | 0:28:47 | |

With each generation, cuckoos improve their mimicry, | 0:28:47 | 0:28:50 | |

while the nest owners become better at spotting a foreign egg. | 0:28:50 | 0:28:54 | |

While many birds are very good | 0:28:56 | 0:28:58 | |

at detecting a strange egg in their nest, | 0:28:58 | 0:29:00 | |

they seem incapable of recognising | 0:29:00 | 0:29:03 | |

the monstrous cuckoo chick as an impostor. | 0:29:03 | 0:29:05 | |

But the deception is not complete. | 0:29:08 | 0:29:11 | |

The young cuckoo is much larger than the reed warbler chick | 0:29:11 | 0:29:14 | |

so it also needs a lot more food. | 0:29:14 | 0:29:17 | |

How does it get enough? | 0:29:17 | 0:29:19 | |

The cuckoo has a solution. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:23 | |

It now uses vocal deception to trick its foster parents | 0:29:23 | 0:29:27 | |

into providing more food. | 0:29:27 | 0:29:29 | |

This is a sonogram of the sound waves produced by a single | 0:29:31 | 0:29:34 | |

reed warbler chick begging for food. | 0:29:34 | 0:29:37 | |

Below it is the call of a cuckoo chick, | 0:29:37 | 0:29:40 | |

and, as you can see, it looks very different. | 0:29:40 | 0:29:43 | |

In fact, it more closely resembles | 0:29:43 | 0:29:47 | |

the calls of a whole nestful of reed warbler chicks. | 0:29:47 | 0:29:51 | |

So, the cuckoo chick's call is a super stimulus | 0:29:53 | 0:29:58 | |

that sounds like a whole nestful of chicks. | 0:29:58 | 0:30:02 | |

And it appears to work. | 0:30:02 | 0:30:04 | |

The adult birds rush back and forth, | 0:30:06 | 0:30:08 | |

providing the impostor with the same amount of food | 0:30:08 | 0:30:11 | |

as they would for an entire brood of their own. | 0:30:11 | 0:30:14 | |

At three weeks old, the cuckoo chick | 0:30:18 | 0:30:21 | |

has spilled out of the nest. | 0:30:21 | 0:30:23 | |

It's now almost eight times the size of its foster parent. | 0:30:23 | 0:30:27 | |

It was over 200 years ago | 0:30:33 | 0:30:35 | |

that Edward Jenner first shocked us | 0:30:35 | 0:30:37 | |

with his revelation of the cuckoo's extraordinary lifestyle. | 0:30:37 | 0:30:41 | |

Now we know that its unusual behaviour | 0:30:43 | 0:30:46 | |

is due to an extraordinary arms race | 0:30:46 | 0:30:48 | |

that has resulted in one of the most fascinating | 0:30:48 | 0:30:51 | |

specialisations in nature. | 0:30:51 | 0:30:53 | |

The cuckoo's success relies on deceiving just two parent birds. | 0:30:59 | 0:31:04 | |

But our second subject is a moth | 0:31:06 | 0:31:08 | |

that is able to deceive hundreds of bees. | 0:31:08 | 0:31:11 | |

How does it infiltrate | 0:31:11 | 0:31:13 | |

one of the most heavily guarded nests in nature? | 0:31:13 | 0:31:16 | |

This wonderful creature was once | 0:31:19 | 0:31:22 | |

one of the most feared insects in Europe. | 0:31:22 | 0:31:25 | |

It's a death's-head hawkmoth, | 0:31:25 | 0:31:27 | |

and it's easy enough to see how it got its name. | 0:31:27 | 0:31:30 | |

It has this mark on its back | 0:31:30 | 0:31:32 | |

that looks just like a human skull. | 0:31:32 | 0:31:35 | |

This gave it a bad reputation that lasted for centuries, | 0:31:35 | 0:31:38 | |

but now there are new ideas about this moth's strange appearance | 0:31:38 | 0:31:42 | |

that may help explain its extraordinary ability | 0:31:42 | 0:31:46 | |

to rob hives without being stung. | 0:31:46 | 0:31:48 | |

Death's-head hawkmoths are a rare sight Britain, | 0:31:52 | 0:31:55 | |

for they spend most of their lives in Africa and Asia. | 0:31:55 | 0:31:58 | |

But every summer a small number of migrants | 0:32:00 | 0:32:02 | |

arrive in northern Europe, | 0:32:02 | 0:32:04 | |

and, if the weather is warm enough, they breed. | 0:32:04 | 0:32:08 | |

Their caterpillars, unlike the drab adult moths, | 0:32:10 | 0:32:14 | |

are beautifully coloured. | 0:32:14 | 0:32:15 | |

After feeding for several weeks | 0:32:18 | 0:32:20 | |

they can grow to a length of 13 centimetres. | 0:32:20 | 0:32:22 | |

Once ready to become adults, they pupate in the soil | 0:32:25 | 0:32:29 | |

and emerge as the sinister, strangely patterned moths. | 0:32:29 | 0:32:33 | |

In the early 19th century, | 0:32:38 | 0:32:40 | |

a region of northern France was hit by a terrible pestilence, | 0:32:40 | 0:32:44 | |

and, at the same time, a large number of hawkmoths | 0:32:44 | 0:32:47 | |

were seen in the area. | 0:32:47 | 0:32:48 | |

The local people linked the deaths to these night-flying insects. | 0:32:48 | 0:32:53 | |

But there was another even more disturbing side to this moth. | 0:32:53 | 0:32:57 | |

It could make an unusual noise. | 0:32:57 | 0:33:00 | |

SQUEAKING | 0:33:01 | 0:33:03 | |

There. | 0:33:03 | 0:33:04 | |

A strange squeak. | 0:33:04 | 0:33:05 | |

And that only added to its chilling reputation. | 0:33:05 | 0:33:09 | |

Moths don't usually squeak. | 0:33:13 | 0:33:15 | |

Tiger moths sometimes produce ultrasonic warning clicks | 0:33:17 | 0:33:21 | |

that tell bats that they're poisonous and not good to eat, | 0:33:21 | 0:33:25 | |

but this is not a noise we can generally hear. | 0:33:25 | 0:33:27 | |

Perhaps the death's-head hawkmoth squeaks | 0:33:29 | 0:33:31 | |

to scare predators like birds. | 0:33:31 | 0:33:33 | |

However, other large migratory moths | 0:33:35 | 0:33:37 | |

don't make such a sound. | 0:33:37 | 0:33:39 | |

This makes the death's-head hawkmoth's squeak | 0:33:41 | 0:33:43 | |

all the more surprising, | 0:33:43 | 0:33:45 | |

and it has intrigued people for centuries. | 0:33:45 | 0:33:48 | |

These moths are more than 200 years old. | 0:33:50 | 0:33:53 | |

We know that because the handwritten label there tells us | 0:33:53 | 0:33:57 | |

they were collected in 1801 by a Robert Darling Willis, | 0:33:57 | 0:34:02 | |

the personal physician to King George III. | 0:34:02 | 0:34:06 | |

George III is well-known as the king | 0:34:06 | 0:34:08 | |

who suffered from bouts of madness, | 0:34:08 | 0:34:10 | |

and, on a visit to see the king during one of them, | 0:34:10 | 0:34:13 | |

Dr Willis discovered these large moths in the monarch's bedchamber. | 0:34:13 | 0:34:17 | |

Unable to identify them, the doctor sent them to his grandson, | 0:34:18 | 0:34:22 | |

who was at that time superintendent | 0:34:22 | 0:34:24 | |

at the Museum of Zoology in Cambridge. | 0:34:24 | 0:34:26 | |

He confirmed that they were death's-head hawkmoths, | 0:34:26 | 0:34:30 | |

and, unusually for an insect, | 0:34:30 | 0:34:33 | |

this moth produces a loud call | 0:34:33 | 0:34:35 | |

that has been likened to the mournful cry | 0:34:35 | 0:34:38 | |

of a grief-stricken child. | 0:34:38 | 0:34:40 | |

Did the disturbed king hear the plaintive calls of a hawkmoth? | 0:34:41 | 0:34:45 | |

That we don't know. | 0:34:45 | 0:34:47 | |

But certainly many of the ordinary people of the 19th century | 0:34:47 | 0:34:50 | |

were struck with a sense of terror whenever this moth appeared. | 0:34:50 | 0:34:54 | |

The moths' unusual appearance and strange behaviour baffled people. | 0:34:56 | 0:35:00 | |

But, in nature, such traits usually have a purpose. | 0:35:02 | 0:35:05 | |

And it may be for the death's-head hawkmoth | 0:35:06 | 0:35:09 | |

that they enable it to break into beehives and steal their honey. | 0:35:09 | 0:35:13 | |

These are the giant honey bees of south-east Asia, | 0:35:15 | 0:35:18 | |

and they form some of the largest bee colonies in the world. | 0:35:18 | 0:35:22 | |

I once got up close to one in order to demonstrate | 0:35:24 | 0:35:27 | |

their response to a predator. | 0:35:27 | 0:35:30 | |

I had a model of a large hornet, | 0:35:30 | 0:35:32 | |

which produced a kind of Mexican wave, | 0:35:32 | 0:35:35 | |

and that makes it very difficult for an aggressor to land. | 0:35:35 | 0:35:38 | |

BUZZING | 0:35:38 | 0:35:40 | |

This covering of bees looks impossible to penetrate. | 0:35:40 | 0:35:44 | |

But at night | 0:35:47 | 0:35:48 | |

a thief can break through their ranks. | 0:35:48 | 0:35:51 | |

A death's-head hawkmoth lands on the carpet of bees | 0:35:51 | 0:35:55 | |

and pushes its way through without being attacked. | 0:35:55 | 0:35:58 | |

In just a few seconds, it takes some sips of honey | 0:35:59 | 0:36:02 | |

and emerges unharmed. | 0:36:02 | 0:36:03 | |

Getting past the guard bees is quite a feat, | 0:36:05 | 0:36:07 | |

but surviving inside is even more astounding. | 0:36:07 | 0:36:11 | |

Death's-head hawkmoths raid domestic beehives too, | 0:36:16 | 0:36:20 | |

and can be quite a pest. | 0:36:20 | 0:36:21 | |

Somehow, the moth slips past the guards and, as if invisible, | 0:36:28 | 0:36:32 | |

walks through the hive, heading straight for the honeycomb. | 0:36:32 | 0:36:36 | |

It then feeds unnoticed. | 0:36:38 | 0:36:40 | |

How does it do this? | 0:36:42 | 0:36:43 | |

One theory proposes that its spooky appearance | 0:36:46 | 0:36:49 | |

may help it avoid being attacked. | 0:36:49 | 0:36:51 | |

BUZZING | 0:36:51 | 0:36:54 | |

Miriam Rothschild, a great entomologist | 0:36:54 | 0:36:56 | |

and expert on fleas and butterflies, | 0:36:56 | 0:36:59 | |

suggested that the moth's skull pattern looks like | 0:36:59 | 0:37:01 | |

the head of a worker bee, | 0:37:01 | 0:37:03 | |

and that this could play a role in the moth's deception. | 0:37:03 | 0:37:07 | |

Well, this is a photograph | 0:37:07 | 0:37:09 | |

of a worker bee face taken through a microscope. | 0:37:09 | 0:37:12 | |

Let's see how it looks next to a close-up photo | 0:37:12 | 0:37:16 | |

of the skull pattern of the moth. | 0:37:16 | 0:37:18 | |

There. | 0:37:21 | 0:37:22 | |

Well, I suppose there's a slight resemblance, | 0:37:22 | 0:37:25 | |

but given the fact that most moths raid beehives and nests | 0:37:25 | 0:37:28 | |

during the night, it's unlikely the bees | 0:37:28 | 0:37:31 | |

could see that much detail. | 0:37:31 | 0:37:33 | |

The most likely answer lies in the scent the moth gives off. | 0:37:33 | 0:37:37 | |

In America in the 1950s, | 0:37:40 | 0:37:42 | |

a German entomologist called Thomas Eisner | 0:37:42 | 0:37:45 | |

studied chemical ecology - in particular, | 0:37:45 | 0:37:48 | |

the chemical defences of insects. | 0:37:48 | 0:37:50 | |

Most famously, he illustrated how bombardier beetles | 0:37:53 | 0:37:57 | |

fire hot acid onto a predator. | 0:37:57 | 0:37:59 | |

He also studied moths, | 0:38:03 | 0:38:05 | |

and showed that the feathery projections on their abdomens | 0:38:05 | 0:38:08 | |

and their large antennae were used to produce and pick up scent. | 0:38:08 | 0:38:12 | |

It seemed that many insects were using scent in surprising ways. | 0:38:13 | 0:38:17 | |

Tests on the chemical scents produced by hawkmoths | 0:38:19 | 0:38:22 | |

reveal a remarkable similarity to those produced by the worker bees | 0:38:22 | 0:38:26 | |

in the hives that they raid. | 0:38:26 | 0:38:28 | |

Their scent is not identical, | 0:38:28 | 0:38:30 | |

but it contains several key chemicals | 0:38:30 | 0:38:32 | |

that exactly match those produced by bees. | 0:38:32 | 0:38:34 | |

So the death's-head hawkmoth's scent | 0:38:37 | 0:38:40 | |

acts as an invisibility cloak | 0:38:40 | 0:38:43 | |

that makes it undetectable to the worker bees in the nest. | 0:38:43 | 0:38:46 | |

With thick scales on its body, | 0:38:51 | 0:38:53 | |

clawed feet that grip the honeycomb, | 0:38:53 | 0:38:55 | |

and a short, pointed proboscis to pierce the honey cells, | 0:38:55 | 0:38:58 | |

the moth has evolved into an effective hive robber. | 0:38:58 | 0:39:02 | |

But there is another, even more impressive impostor | 0:39:05 | 0:39:08 | |

that can also penetrate the protective defences | 0:39:08 | 0:39:11 | |

of an insect colony. | 0:39:11 | 0:39:13 | |

Its victims are not bees but ants. | 0:39:13 | 0:39:16 | |

The impostor that invades this ant nest | 0:39:18 | 0:39:21 | |

doesn't get in there by flying. | 0:39:21 | 0:39:23 | |

Nothing as blatant as that. | 0:39:23 | 0:39:25 | |

Instead, the caterpillars of some species of blue butterfly, | 0:39:25 | 0:39:29 | |

like this one, wait for red ants to collect them. | 0:39:29 | 0:39:34 | |

Remarkably, passing ants don't kill them. | 0:39:34 | 0:39:37 | |

They pick them up and take them back into their nest. | 0:39:37 | 0:39:40 | |

The cuckoo caterpillar will stay inside the nest | 0:39:40 | 0:39:44 | |

for up to ten months. | 0:39:44 | 0:39:46 | |

Just like the death's-head hawkmoths, | 0:39:46 | 0:39:48 | |

it produces a chemical scent that deceives the ants. | 0:39:48 | 0:39:51 | |

This pink caterpillar, which belongs to the alcon blue butterfly, | 0:39:54 | 0:39:58 | |

has been collected because, to them, | 0:39:58 | 0:40:00 | |

it smells just like the young of their own nest. | 0:40:00 | 0:40:04 | |

They become controlled by the impostor's intoxicating scent, | 0:40:04 | 0:40:07 | |

and feed the butterfly larva even more regularly | 0:40:07 | 0:40:10 | |

than they do their own. | 0:40:10 | 0:40:12 | |

There's another way this impostor pulls off its deceptive trick. | 0:40:14 | 0:40:18 | |

When it's inside the nest, | 0:40:18 | 0:40:20 | |

the butterfly larva makes a strange chattering noise. | 0:40:20 | 0:40:24 | |

To our ears, it's very faint, | 0:40:24 | 0:40:25 | |

but it's clear enough to other insects. This is it. | 0:40:25 | 0:40:28 | |

CHATTERING NOISE | 0:40:30 | 0:40:32 | |

And this is the sound that's made by a queen ant. | 0:40:32 | 0:40:36 | |

SIMILAR CHATTERING NOISE | 0:40:38 | 0:40:41 | |

To worker ants, these calls are very similar, | 0:40:43 | 0:40:46 | |

and they react by treating the butterfly larva | 0:40:46 | 0:40:49 | |

as if it's one of their own. | 0:40:49 | 0:40:51 | |

Caterpillars of the blue butterfly are impressive impostors. | 0:40:53 | 0:40:57 | |

Not only do they mimic the scent of the ants, | 0:40:57 | 0:41:00 | |

but their queen's calls too. | 0:41:00 | 0:41:03 | |

This seems to trump the death's-head hawkmoth's ability | 0:41:03 | 0:41:06 | |

as a nest invader. | 0:41:06 | 0:41:08 | |

But the hawkmoth may also be using sound to trick its victims. | 0:41:11 | 0:41:15 | |

Remember the eerie squeak that was thought to be so frightening? | 0:41:18 | 0:41:22 | |

SQUEAKING | 0:41:23 | 0:41:24 | |

There. | 0:41:24 | 0:41:26 | |

The hawkmoth makes this sound inside the beehive | 0:41:26 | 0:41:29 | |

when it enters to steal honey. | 0:41:29 | 0:41:31 | |

It's been suggested that this might calm the bees, | 0:41:31 | 0:41:35 | |

because the squeak is thought to sound like the piping call | 0:41:35 | 0:41:38 | |

that the queen honey bee makes to pacify her workers. | 0:41:38 | 0:41:41 | |

We can't be sure if the call and the strange skull marking | 0:41:43 | 0:41:46 | |

evolved to deceive bees, but we can be certain | 0:41:46 | 0:41:49 | |

that the death's-head hawkmoth's life as an impostor | 0:41:49 | 0:41:52 | |

is more curious than the superstitions | 0:41:52 | 0:41:55 | |

that have surrounded it for hundreds of years. | 0:41:55 | 0:41:58 | |

The cuckoo and the hawkmoth are both audacious impostors, | 0:42:00 | 0:42:04 | |

but the cuckoo's ability to make its victim raise its young | 0:42:04 | 0:42:08 | |

is perhaps the most accomplished deception of all. | 0:42:08 | 0:42:11 |