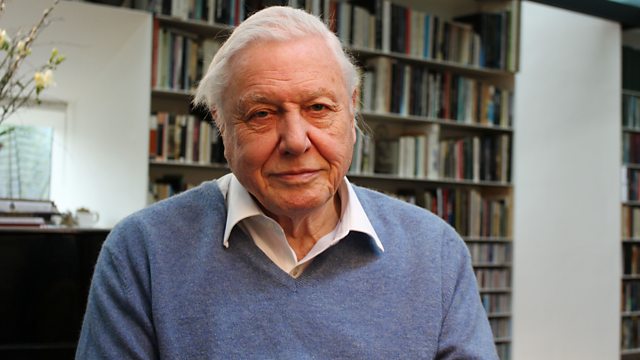

Episode 8 David Attenborough's Natural Curiosities

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Episode 8. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

The natural world is full of extraordinary animals with | 0:00:02 | 0:00:06 | |

amazing life histories. | 0:00:06 | 0:00:09 | |

Yet certain stories are more intriguing than most. | 0:00:09 | 0:00:12 | |

The mysteries of a butterfly's life cycle. | 0:00:15 | 0:00:18 | |

Or the strange biology of the emperor penguin. | 0:00:19 | 0:00:21 | |

Some of these creatures were surrounded by myth | 0:00:23 | 0:00:25 | |

and misunderstandings for a very long time. | 0:00:25 | 0:00:28 | |

And some have only recently revealed their secrets. | 0:00:29 | 0:00:33 | |

These are the animals that stand out from the crowd. | 0:00:34 | 0:00:38 | |

The curiosities I find most fascinating of all. | 0:00:38 | 0:00:42 | |

Some animals have intriguing ways of protecting their skin. | 0:00:50 | 0:00:56 | |

The hippopotamus lives in Africa under the hot tropical sun, | 0:00:56 | 0:01:00 | |

yet doesn't get sunburnt. | 0:01:00 | 0:01:03 | |

And capuchin monkeys live in insect-infested jungles, | 0:01:03 | 0:01:06 | |

but hardly ever get bitten. | 0:01:06 | 0:01:09 | |

How do these animals beat the elements | 0:01:10 | 0:01:12 | |

and protect themselves from sun, parasites, and disease? | 0:01:12 | 0:01:16 | |

And also in this programme, | 0:01:20 | 0:01:22 | |

some animals can perform amazing physical feats. | 0:01:22 | 0:01:26 | |

A flea's jump is said to be the equivalent of a man leaping | 0:01:26 | 0:01:30 | |

over St Paul's cathedral. | 0:01:30 | 0:01:32 | |

And it's famously quoted that cheetahs can run at speeds of 70mph. | 0:01:32 | 0:01:37 | |

But are these claims really true? | 0:01:39 | 0:01:42 | |

Hippos are large land mammals that can weigh up to three tonnes. | 0:01:50 | 0:01:55 | |

And they need to keep their huge bodies cool | 0:01:55 | 0:01:57 | |

and protected from the sun. | 0:01:57 | 0:02:00 | |

To avoid the heat, they spend much of the day swimming, | 0:02:00 | 0:02:03 | |

as they are doing now in the waters behind me. | 0:02:03 | 0:02:06 | |

But when they're on land, strangely they don't appear to get sunburnt. | 0:02:06 | 0:02:10 | |

The secret of their sun tolerance lies within their skin | 0:02:12 | 0:02:16 | |

that can sometimes appear shiny and greasy. | 0:02:16 | 0:02:19 | |

It has unique properties that shocked the early explorers | 0:02:19 | 0:02:23 | |

and now excites modern scientists. | 0:02:23 | 0:02:26 | |

Hippos live in Africa, south of the Sahara, | 0:02:30 | 0:02:33 | |

where temperatures can reach 40 degrees centigrade. | 0:02:33 | 0:02:37 | |

But they spend much of the day submerged in rivers, | 0:02:37 | 0:02:40 | |

lakes and swamps, and so avoid the worst of the sun's rays. | 0:02:40 | 0:02:45 | |

They possess formidable teeth, but they are in fact herbivores | 0:02:48 | 0:02:53 | |

and eat mostly grass, great quantities of it. | 0:02:53 | 0:02:56 | |

And they graze mostly at night. | 0:02:56 | 0:02:58 | |

Even so, continually moving in and out of water, together with being | 0:03:00 | 0:03:05 | |

roasted by the rays of the sun, could be very damaging to their skin. | 0:03:05 | 0:03:09 | |

But curiously, hippos remain healthy. | 0:03:11 | 0:03:13 | |

Throughout history, | 0:03:19 | 0:03:20 | |

the hippopotamus has been the subject of many strange tales. | 0:03:20 | 0:03:24 | |

The Greeks claimed they sweated blood, and the Romans said | 0:03:24 | 0:03:28 | |

they deliberately pierced their skin on sharp rushes to release blood. | 0:03:28 | 0:03:33 | |

It seemed bizarre that an animal would make itself bleed on purpose. | 0:03:33 | 0:03:37 | |

In the 19th century, one special hippopotamus allowed people | 0:03:39 | 0:03:43 | |

to get a closer look at these strange skin secretions. | 0:03:43 | 0:03:46 | |

In 1849, the British consul for Egypt, Charles Augustus Murray, | 0:03:50 | 0:03:55 | |

formally requested that the Pasha of Egypt helped capture | 0:03:55 | 0:03:59 | |

a hippo for the Zoological Society of London. | 0:03:59 | 0:04:03 | |

Hunters searched the reeds on a remote island called Obaysch. | 0:04:03 | 0:04:07 | |

2,000km up the Nile from Cairo, | 0:04:08 | 0:04:13 | |

they discovered a male hippo that was only a few days old. | 0:04:13 | 0:04:18 | |

When they tried to grab it, a strange thing happened. | 0:04:18 | 0:04:21 | |

Murray describes how, "A slimy exudation lavishly poured forth | 0:04:21 | 0:04:26 | |

"from the innumerable pores in the skin, | 0:04:26 | 0:04:29 | |

"rendering it so slippery that the animal was impossible to hold." | 0:04:29 | 0:04:34 | |

The hunters dropped the baby hippo back into the waters of the Nile, | 0:04:34 | 0:04:38 | |

but they managed to retrieve it again, using the hook of a spear. | 0:04:38 | 0:04:43 | |

The prized hippo was named Obaysch after the island of its capture, | 0:04:43 | 0:04:48 | |

and here he is. | 0:04:48 | 0:04:50 | |

Before his capture, young Obaysch lived with his mother. | 0:04:55 | 0:04:59 | |

She had moved away from the herd to give birth alone, | 0:04:59 | 0:05:02 | |

and she protected him from lions and crocodiles. | 0:05:02 | 0:05:06 | |

Whether Obaysch became accidentally separated from his mother, | 0:05:06 | 0:05:09 | |

we'll never know, | 0:05:09 | 0:05:11 | |

but we do know that secretions from his skin made him | 0:05:11 | 0:05:14 | |

so slippery that he very nearly escaped capture. | 0:05:14 | 0:05:17 | |

At this time, very little was known about hippos, | 0:05:19 | 0:05:22 | |

and many people believed that they were some kind of horse | 0:05:22 | 0:05:26 | |

that had taken to living in rivers. | 0:05:26 | 0:05:28 | |

In the early 20th century, | 0:05:30 | 0:05:32 | |

naturalists decided that they were closely related to pigs. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:36 | |

DNA evidence, however, now shows that, in fact, their ancestors | 0:05:37 | 0:05:42 | |

were cetaceans - the group that contains whales and dolphins - | 0:05:42 | 0:05:49 | |

so hippos still retain many adaptations for a life in water. | 0:05:49 | 0:05:54 | |

Hippos are very heavy animals | 0:05:58 | 0:06:01 | |

but, for most of their time, their bodies are supported by water. | 0:06:01 | 0:06:05 | |

They're not really very good swimmers. | 0:06:05 | 0:06:07 | |

In the water, they move by bounding across the bottom. | 0:06:07 | 0:06:11 | |

They're well adapted to a semi-aquatic life | 0:06:11 | 0:06:15 | |

because their ears, their eyes, and their nostrils are all towards | 0:06:15 | 0:06:19 | |

the top of the head, which enables them to lie almost totally submerged | 0:06:19 | 0:06:24 | |

and yet still keep notice of what's going on on land, | 0:06:24 | 0:06:28 | |

but their skin is almost entirely hairless, | 0:06:28 | 0:06:31 | |

so, on land, it has to be kept moist. | 0:06:31 | 0:06:34 | |

In order to prevent young Obaysch from sunburn and drying out, | 0:06:38 | 0:06:43 | |

the Egyptian Pasha had a boat built with a bathing pool, | 0:06:43 | 0:06:46 | |

to transport Obaysch in comfort all the way down the River Nile. | 0:06:46 | 0:06:51 | |

Accompanied by several cows to supply him with milk, | 0:06:52 | 0:06:55 | |

he arrived safely in Cairo four months later. | 0:06:55 | 0:06:59 | |

On receiving Obaysch, | 0:07:02 | 0:07:03 | |

the British Consul wrote excitedly to the Zoological Society of London, | 0:07:03 | 0:07:08 | |

confirming that the hippo was alive, and as tame and playful as a puppy. | 0:07:08 | 0:07:13 | |

But his travels were not yet over. | 0:07:13 | 0:07:17 | |

In the spring of 1850, Obaysch was taken to Alexandria, | 0:07:17 | 0:07:21 | |

to board a P&O steamship called the Ripon. | 0:07:21 | 0:07:25 | |

A special hippo house with a water tank was built on the deck | 0:07:25 | 0:07:28 | |

and, in May, Obaysch arrived safely in Southampton. | 0:07:28 | 0:07:32 | |

With the help of a block and tackle, | 0:07:32 | 0:07:34 | |

he was loaded onto a train bound for London, | 0:07:34 | 0:07:38 | |

and at 10 o'clock at night, | 0:07:38 | 0:07:39 | |

the tired hippo and his keeper reached London Zoo. | 0:07:39 | 0:07:43 | |

His home was a newly constructed enclosure, | 0:07:44 | 0:07:47 | |

complete with a heated swimming pool. | 0:07:47 | 0:07:50 | |

After many hours of travelling, | 0:07:50 | 0:07:52 | |

the hippo gratefully plunged into the water. | 0:07:52 | 0:07:54 | |

Obaysch, the hippo sensation, had arrived. | 0:07:54 | 0:07:58 | |

A journey of over 5,000 miles, by sailboat, steamboat and a train, | 0:08:02 | 0:08:08 | |

brought a hippo to England - | 0:08:08 | 0:08:10 | |

the first one since Roman times. | 0:08:10 | 0:08:13 | |

Now, Europeans had a chance to get close to this unusual creature | 0:08:15 | 0:08:19 | |

and perhaps learn more about its strange skin secretions. | 0:08:19 | 0:08:24 | |

Later, more hippos arrived at other zoos, | 0:08:25 | 0:08:29 | |

and the blood-red sweat was seen again. | 0:08:29 | 0:08:31 | |

In the cooler climate of Europe, | 0:08:32 | 0:08:35 | |

hippos don't sweat very much | 0:08:35 | 0:08:37 | |

but, zookeepers have reported that, sometimes, in the morning, | 0:08:37 | 0:08:40 | |

they see red trickles forming on the flanks of these animals. | 0:08:40 | 0:08:45 | |

It comes from particularly large pores, | 0:08:45 | 0:08:49 | |

which form streaks on the animal's side, | 0:08:49 | 0:08:52 | |

which does look a little like blood. | 0:08:52 | 0:08:57 | |

We've known for some time that this is a... | 0:08:57 | 0:09:00 | |

a moisturiser, but why it's red has only just been discovered. | 0:09:00 | 0:09:05 | |

A little more. | 0:09:07 | 0:09:09 | |

Come on. | 0:09:09 | 0:09:10 | |

There we go. | 0:09:10 | 0:09:11 | |

Recently, Japanese scientists were intrigued to see | 0:09:13 | 0:09:16 | |

photos of a wild baby hippo with light pink skin | 0:09:16 | 0:09:20 | |

that still didn't burn under the harsh African sun. | 0:09:20 | 0:09:24 | |

They wondered if the red secretion played | 0:09:24 | 0:09:27 | |

a role in protecting its pale skin, | 0:09:27 | 0:09:30 | |

so they collected hippo secretion from captive hippos | 0:09:30 | 0:09:33 | |

to look at its composition. | 0:09:33 | 0:09:36 | |

They discovered two pigments - | 0:09:36 | 0:09:38 | |

a red one, that they named hipposudoric acid, | 0:09:38 | 0:09:41 | |

and an orange one, that they called norhipposudoric acid. | 0:09:41 | 0:09:46 | |

The red pigment was found to absorb harmful wavelengths of light | 0:09:47 | 0:09:52 | |

and both pigments were antibacterial. | 0:09:52 | 0:09:54 | |

Here was the answer to why hippos never got sunburnt | 0:09:57 | 0:10:01 | |

and why the wounds of battling males rarely became infected. | 0:10:01 | 0:10:05 | |

HIPPOS GRUNT | 0:10:05 | 0:10:08 | |

The mysterious slime is neither blood nor sweat, | 0:10:08 | 0:10:12 | |

but a specialised secretion that turns red in sunlight | 0:10:12 | 0:10:15 | |

and protects the hippos' skin. | 0:10:15 | 0:10:17 | |

HIPPOS GRUNT | 0:10:17 | 0:10:20 | |

So, what became of Obaysch, the first ever hippo in captivity | 0:10:20 | 0:10:25 | |

that gave us a close-up view of these curious creatures? | 0:10:25 | 0:10:29 | |

For several years, he was a sensation at the London Zoo. | 0:10:29 | 0:10:33 | |

He even inspired the Hippo Polka, a popular dance of its time, | 0:10:33 | 0:10:39 | |

but visitors grew weary of him. | 0:10:39 | 0:10:42 | |

Some were disappointed not to see a giant river-horse | 0:10:42 | 0:10:46 | |

and others expected a ferocious beast, not a gentle giant. | 0:10:46 | 0:10:50 | |

Obaysch died in 1878 at the age of 28, | 0:10:50 | 0:10:54 | |

and he and others that followed | 0:10:54 | 0:10:56 | |

taught us some intriguing things about hippos, | 0:10:56 | 0:10:59 | |

including the reason for the blood-red droplets | 0:10:59 | 0:11:01 | |

found on their skin. HIPPOS GRUNT | 0:11:01 | 0:11:05 | |

So, hippos can produce their very own natural sun cream | 0:11:05 | 0:11:09 | |

that is waterproof, moisturising and antibacterial. | 0:11:09 | 0:11:13 | |

Next, we meet another animal that has its own natural cure. | 0:11:16 | 0:11:21 | |

Capuchin monkeys have a surprising way of protecting their skin | 0:11:21 | 0:11:25 | |

from stings and bites. | 0:11:25 | 0:11:27 | |

MONKEYS SCREECH | 0:11:27 | 0:11:29 | |

When early explorers reached the Americas in the 15th century, | 0:11:31 | 0:11:35 | |

they encountered small monkeys | 0:11:35 | 0:11:37 | |

with patches of dark brown fur on their heads that resembled hoods, | 0:11:37 | 0:11:43 | |

so they named them after a group of Franciscan friars | 0:11:43 | 0:11:46 | |

called Capuchin monks. | 0:11:46 | 0:11:48 | |

Capuchin monkeys quickly charmed their way into our hearts. | 0:11:52 | 0:11:57 | |

With dextrous hands and inquisitive personalities, | 0:11:57 | 0:12:00 | |

they seemed very humanlike. | 0:12:00 | 0:12:02 | |

They were also adept at learning tricks | 0:12:04 | 0:12:07 | |

and soon became popular performers on our streets. | 0:12:07 | 0:12:10 | |

MONKEY SQUEAKS | 0:12:14 | 0:12:16 | |

In the past, we used to teach monkeys how to do things - | 0:12:16 | 0:12:21 | |

how to perform tricks - | 0:12:21 | 0:12:23 | |

but things are different today. | 0:12:23 | 0:12:26 | |

Today, monkeys are teaching us things. | 0:12:26 | 0:12:30 | |

Watch what happens when I give them a few spring onions | 0:12:30 | 0:12:36 | |

and some chilli peppers. | 0:12:36 | 0:12:38 | |

MONKEYS SQUEAK | 0:12:38 | 0:12:42 | |

MONKEY SQUEAKS | 0:12:51 | 0:12:53 | |

They're clearly not eating what I offered them. | 0:13:09 | 0:13:11 | |

They're rubbing themselves with the peppers and the onions. | 0:13:11 | 0:13:16 | |

You might think that that's because they're captive monkeys, | 0:13:16 | 0:13:19 | |

and they are just doing that to entertain themselves, | 0:13:19 | 0:13:22 | |

but not so. | 0:13:22 | 0:13:24 | |

I've seen capuchins do just that in the wild. | 0:13:24 | 0:13:27 | |

MONKEYS SQUEAK | 0:13:39 | 0:13:42 | |

These white-faced capuchins in Costa Rica | 0:13:42 | 0:13:45 | |

reacted in much the same way | 0:13:45 | 0:13:47 | |

when they came across a particular rainforest plant - the piper plant. | 0:13:47 | 0:13:52 | |

These leaves have a distinctive liquorice scent | 0:13:55 | 0:13:58 | |

and they are hard to come by, so when they do find them, | 0:13:58 | 0:14:01 | |

the monkeys passed the leaves around the troop | 0:14:01 | 0:14:04 | |

so that everyone can have a share. | 0:14:04 | 0:14:06 | |

MONKEYS CHATTER | 0:14:06 | 0:14:08 | |

Both in the wild and in captivity, | 0:14:11 | 0:14:14 | |

capuchin monkeys become similarly excited | 0:14:14 | 0:14:17 | |

at the sight of lemons or limes, | 0:14:17 | 0:14:19 | |

and, again, the same frenzied activity and fur-rubbing follows. | 0:14:19 | 0:14:24 | |

What is it about these plants that gets the monkeys so excited? | 0:14:28 | 0:14:32 | |

We know they all give off a pungent smell, | 0:14:36 | 0:14:39 | |

so could this be what the capuchins are after? | 0:14:39 | 0:14:42 | |

LEMURS SQUEAL | 0:14:42 | 0:14:45 | |

Smell plays an important part in the lives of many primates, | 0:14:45 | 0:14:49 | |

but none more so than in the lives | 0:14:49 | 0:14:51 | |

of these lovely ring-tailed lemurs. LEMURS CHATTER | 0:14:51 | 0:14:55 | |

They use it both to establish their position within the troop | 0:14:55 | 0:14:59 | |

and also the boundaries - the frontiers - of their territory. | 0:14:59 | 0:15:04 | |

If you look at the inside of their forearms, | 0:15:04 | 0:15:06 | |

there's a black patch without fur, and there, | 0:15:06 | 0:15:09 | |

the skin is loaded with glands that produce a very strong smell, | 0:15:09 | 0:15:15 | |

and when these boys go into battle... Whoops! | 0:15:15 | 0:15:17 | |

When they go into battle, | 0:15:17 | 0:15:19 | |

they draw their furry tail through their forearms, | 0:15:19 | 0:15:23 | |

loading it with scent from those glands, | 0:15:23 | 0:15:25 | |

and then they wave it over their backs | 0:15:25 | 0:15:28 | |

in the direction of their enemies, in a kind of stink fight. | 0:15:28 | 0:15:32 | |

You understand that, don't you? | 0:15:34 | 0:15:35 | |

LEMURS SQUEAK Oh! | 0:15:35 | 0:15:38 | |

LEMURS CHIRP The pungent scent is also used | 0:15:42 | 0:15:44 | |

by males during the mating season. | 0:15:44 | 0:15:47 | |

This male has rubbed his own distinctive smell onto his tail | 0:15:47 | 0:15:51 | |

and he now wafts over towards a female to signal his intentions... | 0:15:51 | 0:15:56 | |

LEMUR SQUEALS ..but she is not entirely convinced. | 0:15:57 | 0:16:01 | |

Unlike lemurs, capuchins don't have scent glands, | 0:16:04 | 0:16:08 | |

so some thought that they could be | 0:16:08 | 0:16:10 | |

using the smell of certain plants | 0:16:10 | 0:16:12 | |

for communication... MONKEYS CHATTER | 0:16:12 | 0:16:14 | |

..but it turns out that they have a different perfume for that job - | 0:16:14 | 0:16:19 | |

urine, which they apply lavishly to their fur. | 0:16:19 | 0:16:24 | |

So, why, then, do they also anoint themselves with other smells? | 0:16:24 | 0:16:29 | |

The answer may be found in our own history. | 0:16:29 | 0:16:33 | |

The early Romans noticed some 2,000 years ago that the fruits | 0:16:34 | 0:16:38 | |

and leaves of the lemon plant have an exceptionally strong scent | 0:16:38 | 0:16:43 | |

that could be used to ward off insects. | 0:16:43 | 0:16:45 | |

A further clue as to why capuchins might cover themselves | 0:16:47 | 0:16:50 | |

in such pungent smells comes from this plant - | 0:16:50 | 0:16:54 | |

the piper plant. | 0:16:54 | 0:16:56 | |

Throughout the Amazon, | 0:16:56 | 0:16:58 | |

Indian tribes apply it as an antiseptic on wounds, | 0:16:58 | 0:17:03 | |

and in Costa Rica, it's used as an insect repellent. | 0:17:03 | 0:17:07 | |

Could it be that capuchin monkeys protect themselves | 0:17:07 | 0:17:11 | |

against the onslaught of mosquitoes in much the same way | 0:17:11 | 0:17:13 | |

as humans do by rubbing themselves with mosquito repellent? | 0:17:13 | 0:17:18 | |

In 1993, scientists at Oxford University | 0:17:23 | 0:17:27 | |

decided to put the question to the test. | 0:17:27 | 0:17:30 | |

They collected some feather lice | 0:17:31 | 0:17:34 | |

and put them into petri dishes overnight. | 0:17:34 | 0:17:36 | |

Into one dish, | 0:17:38 | 0:17:40 | |

they also placed a slice of lime. | 0:17:40 | 0:17:43 | |

The next day, the lice without the lime were mostly alive, | 0:17:46 | 0:17:51 | |

whilst, in the other dish, two thirds had died | 0:17:51 | 0:17:55 | |

and the remainder were paralysed. | 0:17:55 | 0:17:58 | |

Clearly, the lime contains a lethal insecticide. | 0:17:58 | 0:18:02 | |

Today, we know that citrus-fruit peel | 0:18:05 | 0:18:09 | |

does indeed contain insecticides, | 0:18:09 | 0:18:11 | |

which disrupt the nervous system of many small insects, | 0:18:11 | 0:18:14 | |

causing them to become uncoordinated and paralysed. | 0:18:14 | 0:18:17 | |

The leaves of the piper plant are antiseptic | 0:18:19 | 0:18:21 | |

and contain substances that protect against fungal | 0:18:21 | 0:18:24 | |

and bacterial infection, | 0:18:24 | 0:18:27 | |

and chilli pepper extract is commonly used in households | 0:18:27 | 0:18:31 | |

and gardens to deter small mammals and insect pests. | 0:18:31 | 0:18:35 | |

So, it seems that the clever monkeys know exactly how to make | 0:18:38 | 0:18:41 | |

the best use of nature's remedies. MONKEYS SQUEAK | 0:18:41 | 0:18:45 | |

Recent research has also revealed | 0:18:45 | 0:18:47 | |

that capuchins anoint themselves far more during the wet season, | 0:18:47 | 0:18:50 | |

when mosquitoes are more abundant and the risk of infection is higher. | 0:18:50 | 0:18:55 | |

Troops use different plants, possibly, simply, | 0:18:56 | 0:19:00 | |

because they have to use what's locally available. | 0:19:00 | 0:19:03 | |

But there's one substance with insect-repellent qualities | 0:19:03 | 0:19:07 | |

that appeals to primates, including capuchins, | 0:19:07 | 0:19:10 | |

that comes not from a plant but from an animal - | 0:19:10 | 0:19:14 | |

an animal like this - | 0:19:14 | 0:19:18 | |

a giant millipede. | 0:19:18 | 0:19:20 | |

When attacked or in danger, | 0:19:20 | 0:19:22 | |

tropical millipedes often produce a powerful defensive secretion... | 0:19:22 | 0:19:28 | |

MONKEYS SCREECH ..and black lemurs have worked out | 0:19:28 | 0:19:30 | |

how to use this to their advantage. | 0:19:30 | 0:19:32 | |

When they find a millipede, | 0:19:35 | 0:19:36 | |

they give it a gentle bite to the head | 0:19:36 | 0:19:38 | |

to make it release its secretion, | 0:19:38 | 0:19:40 | |

and then rub this through their fur. | 0:19:40 | 0:19:43 | |

The toxic fluid has a strong smell | 0:19:43 | 0:19:46 | |

and is highly irritating... LEMURS SCREECH | 0:19:46 | 0:19:48 | |

..but it protects the lemurs against mosquitoes. | 0:19:48 | 0:19:51 | |

This pungent secretion has apparently another strange effect - | 0:19:53 | 0:19:58 | |

it seems to act as a narcotic, | 0:19:58 | 0:20:00 | |

sending the lemur into a kind of trance. | 0:20:00 | 0:20:04 | |

Like other drugs, | 0:20:04 | 0:20:05 | |

it has powerful side effects. | 0:20:05 | 0:20:07 | |

We still don't understand how capuchins and lemurs | 0:20:10 | 0:20:13 | |

select the plants that they use for medicinal purposes. | 0:20:13 | 0:20:17 | |

These capuchins behind me were born and raised in captivity, | 0:20:17 | 0:20:21 | |

so they never encountered the plants that their parents | 0:20:21 | 0:20:24 | |

and ancestors would have used. | 0:20:24 | 0:20:27 | |

So, how do the monkeys know | 0:20:28 | 0:20:30 | |

which plants to choose? MONKEYS CHATTER | 0:20:30 | 0:20:32 | |

Can they detect particular substances in them | 0:20:32 | 0:20:35 | |

or is it something they learn from others? | 0:20:35 | 0:20:38 | |

We don't yet know the answers, | 0:20:38 | 0:20:40 | |

but it could be that babies learn by watching the adults | 0:20:40 | 0:20:43 | |

and that it's passed down the family line. | 0:20:43 | 0:20:46 | |

It's clearly a great social event, | 0:20:48 | 0:20:50 | |

with everyone joining in | 0:20:50 | 0:20:54 | |

and, afterwards, the entire group appears to be more tightly bonded. | 0:20:54 | 0:20:59 | |

MONKEYS SQUEAK | 0:20:59 | 0:21:01 | |

When Europeans first saw monkeys in the wild, | 0:21:03 | 0:21:07 | |

they thought that they were imitating what people did | 0:21:07 | 0:21:10 | |

in some of their behaviours, but quite the reverse. | 0:21:10 | 0:21:14 | |

It now turns out that many of the local people did things | 0:21:14 | 0:21:18 | |

that the monkeys had taught them - | 0:21:18 | 0:21:20 | |

using plants as medicines - | 0:21:20 | 0:21:23 | |

so it seems that clever monkeys have taught us a trick or two. | 0:21:23 | 0:21:27 | |

Quick! Look! | 0:21:51 | 0:21:53 | |

This is a real live flea circus, | 0:21:53 | 0:21:57 | |

and you can see this one pulling along this tiny chariot. | 0:21:57 | 0:22:02 | |

There are very few circuses like this these days. | 0:22:02 | 0:22:07 | |

The whole business of performing fleas dates back | 0:22:07 | 0:22:10 | |

into the 16th century, | 0:22:10 | 0:22:11 | |

and it was used by watchmakers, | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

who used them to demonstrate how they themselves could | 0:22:14 | 0:22:17 | |

work on a near-miniature scale. | 0:22:17 | 0:22:19 | |

They used thin gold wires to harness fleas | 0:22:19 | 0:22:23 | |

and then linked the fleas to tiny chains. | 0:22:23 | 0:22:26 | |

Early magnifying devices like this | 0:22:27 | 0:22:29 | |

were actually named fleaglasses after these pests, | 0:22:29 | 0:22:34 | |

and the fleas were excellent creatures to | 0:22:34 | 0:22:37 | |

demonstrate a newly-visible microscopic world. | 0:22:37 | 0:22:41 | |

Fleas appear to be extraordinarily strong. | 0:22:41 | 0:22:45 | |

After all, this little badger flea here, pulling this chariot - | 0:22:45 | 0:22:50 | |

what an extraordinary thing. | 0:22:50 | 0:22:52 | |

That's the equivalent to me trying to pull a jumbo jet single-handed. | 0:22:52 | 0:22:56 | |

And this tiny merry-go-round - | 0:22:56 | 0:22:58 | |

that, too, is completely powered by fleas. | 0:22:58 | 0:23:01 | |

The secret of the fleas' strength and ability to move such equipment | 0:23:04 | 0:23:09 | |

lies in their powerful walking and jumping techniques. | 0:23:09 | 0:23:13 | |

They have the ability to store and then release energy, | 0:23:13 | 0:23:18 | |

and that enables them to leap upwards with great acceleration. | 0:23:18 | 0:23:22 | |

Fleas need to be good jumpers. | 0:23:24 | 0:23:27 | |

They live on the skin of mammals and birds, sucking their blood, | 0:23:27 | 0:23:31 | |

so they have to be able to quickly leap onboard their travelling hosts | 0:23:31 | 0:23:35 | |

when they get the chance. | 0:23:35 | 0:23:37 | |

There are more than 2,500 species worldwide, | 0:23:38 | 0:23:42 | |

62 of which live in Britain. | 0:23:42 | 0:23:45 | |

Fortunately, only a few feed on us. | 0:23:45 | 0:23:49 | |

Rat fleas were said to be responsible | 0:23:55 | 0:23:57 | |

for the spread of the Black Death in 1665, which killed millions, | 0:23:57 | 0:24:05 | |

but it wasn't until the invention of the magnifying glass | 0:24:05 | 0:24:08 | |

that we were able to see these tiny creatures face-to-face. | 0:24:08 | 0:24:12 | |

In 1665, Robert Hooke, an inventor and natural philosopher, | 0:24:13 | 0:24:19 | |

made one of the first compound microscopes. | 0:24:19 | 0:24:22 | |

This is a later reproduction of it. | 0:24:22 | 0:24:24 | |

And he then published his discoveries that he made using it | 0:24:24 | 0:24:28 | |

in a marvellous book called Micrographia. | 0:24:28 | 0:24:32 | |

It became one of the first scientific bestsellers. | 0:24:32 | 0:24:36 | |

Samuel Pepys mentioned it in his diary, | 0:24:36 | 0:24:39 | |

and it contained magnificent, detailed drawings | 0:24:39 | 0:24:42 | |

that revealed biological structures that had never been seen before. | 0:24:42 | 0:24:46 | |

He saw that plant tissue was made up of little units | 0:24:46 | 0:24:50 | |

that he called cells - the word we still use - | 0:24:50 | 0:24:54 | |

and he drew this marvellously detailed flea, | 0:24:54 | 0:24:58 | |

showing its great, strikingly long legs. | 0:24:58 | 0:25:01 | |

He also watched it through the microscope | 0:25:03 | 0:25:06 | |

and he described how a flea jumped. | 0:25:06 | 0:25:09 | |

This is what he says... | 0:25:09 | 0:25:11 | |

"When the flea intends to leap, he folds up these six legs together, | 0:25:11 | 0:25:17 | |

"then springs them all out at the same instant, | 0:25:17 | 0:25:20 | |

"and thereby exerting his whole strength at once, | 0:25:20 | 0:25:24 | |

"carries his little body to a considerable distance." | 0:25:24 | 0:25:28 | |

And indeed he does. | 0:25:28 | 0:25:30 | |

A flea's jump takes just one thousandth of a second, | 0:25:36 | 0:25:40 | |

so Hooke must have had very sharp eyesight to see it. | 0:25:40 | 0:25:44 | |

Many researchers have been fascinated by fleas, | 0:25:47 | 0:25:50 | |

and for one particular family, they became an obsession. | 0:25:50 | 0:25:54 | |

Charles Rothschild, a banker and keen naturalist, | 0:25:55 | 0:25:58 | |

amassed over 30,000 specimens | 0:25:58 | 0:26:01 | |

and identified more than 500 new species. | 0:26:01 | 0:26:05 | |

He purchased them from specialist traders worldwide, | 0:26:09 | 0:26:12 | |

and one parcel from America had a special surprise - | 0:26:12 | 0:26:17 | |

the tiny fleas were dressed as Mexicans. | 0:26:17 | 0:26:20 | |

Miriam, Charles's daughter, shared his passion for fleas | 0:26:29 | 0:26:33 | |

and catalogued his whole collection. | 0:26:33 | 0:26:36 | |

She looked closely at the flea's body and the way they jumped, | 0:26:36 | 0:26:39 | |

and was puzzled to find that they could leap far higher than | 0:26:39 | 0:26:42 | |

should theoretically have been possible, | 0:26:42 | 0:26:45 | |

but could their reputation for jumping 200 times their body length | 0:26:45 | 0:26:49 | |

possibly be true? | 0:26:49 | 0:26:51 | |

Most of the natural world's top jumpers | 0:26:56 | 0:26:58 | |

achieve their impressive leaps by using straightforward muscle power. | 0:26:58 | 0:27:02 | |

Kangaroos can make single bounds of almost eight metres | 0:27:03 | 0:27:08 | |

and frogs are able to jump more than 20 times their body length. | 0:27:08 | 0:27:13 | |

The jumping spider's leap is even more impressive - | 0:27:20 | 0:27:23 | |

100 times its own length. | 0:27:23 | 0:27:26 | |

It achieves this by exploiting hydraulics, | 0:27:26 | 0:27:30 | |

and scientists had long suspected that fleas and other insects | 0:27:30 | 0:27:34 | |

also needed something other than muscle to make their huge jumps. | 0:27:34 | 0:27:39 | |

In the 1960s, an exciting discovery was made in the insect world | 0:27:44 | 0:27:48 | |

that helped explain how bigger flying insects, | 0:27:48 | 0:27:51 | |

like locusts and dragonflies, | 0:27:51 | 0:27:53 | |

were able to fly and jump so well. | 0:27:53 | 0:27:56 | |

A rubbery protein was found in the hinges and joints | 0:27:56 | 0:28:00 | |

of locusts' wings and legs. | 0:28:00 | 0:28:03 | |

Using ultraviolet light, it's possible to see it, | 0:28:03 | 0:28:06 | |

as in this picture of the leg joint of a locust. | 0:28:06 | 0:28:10 | |

Here, that blue is this new substance. | 0:28:10 | 0:28:14 | |

But, just like this rubber, | 0:28:14 | 0:28:16 | |

it could bend and then release energy, | 0:28:16 | 0:28:20 | |

but the newly discovered material did that | 0:28:20 | 0:28:23 | |

with more than 90% efficiency. | 0:28:23 | 0:28:26 | |

Remarkably, too, it repeatedly snapped back into shape | 0:28:26 | 0:28:29 | |

without any deformation. | 0:28:29 | 0:28:31 | |

It was named resilin. | 0:28:31 | 0:28:33 | |

This stretchy protein allows insects to bend their stiff bodies | 0:28:35 | 0:28:39 | |

and stretch their tendons without snapping. | 0:28:39 | 0:28:42 | |

It's so robust, it lasts a lifetime, | 0:28:44 | 0:28:47 | |

and it's believed to be the most efficient elastic protein known. | 0:28:47 | 0:28:51 | |

The discovery of resilin opened up a whole new area of study, | 0:28:54 | 0:28:59 | |

and in 1966, Henry Bennet-Clark, | 0:28:59 | 0:29:03 | |

an expert in insect biomechanics, | 0:29:03 | 0:29:06 | |

had a breakthrough moment. | 0:29:06 | 0:29:08 | |

He had the chance to see some exciting new footage of fleas, | 0:29:09 | 0:29:13 | |

shot on a newly invented | 0:29:13 | 0:29:15 | |

high-speed camera. | 0:29:15 | 0:29:16 | |

Bennet-Clark studied the new flea footage | 0:29:18 | 0:29:21 | |

and built a mechanical model 400 times bigger than the flea. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:26 | |

He calculated that the fleas were somehow generating | 0:29:26 | 0:29:29 | |

much more power than their muscles could actually provide. | 0:29:29 | 0:29:33 | |

He noticed that, just before leaping, | 0:29:33 | 0:29:36 | |

the flea bent the closest segment of its hindmost legs towards the body | 0:29:36 | 0:29:41 | |

and hesitated for about a tenth of a second. | 0:29:41 | 0:29:44 | |

Carefully, he dissected fleas and found a pad of material, | 0:29:44 | 0:29:49 | |

and that proved to be resilin. | 0:29:49 | 0:29:52 | |

He proposed that fleas stored some of the energy for their jumps | 0:29:52 | 0:29:55 | |

in this rubberlike tissue, | 0:29:55 | 0:29:57 | |

and then released it as they pushed off with their shins and feet. | 0:29:57 | 0:30:00 | |

So, the tiny wingless fleas use internal resilin springs | 0:30:04 | 0:30:09 | |

like those of other, bigger, flying and jumping insects, | 0:30:09 | 0:30:14 | |

and the secret of their huge leaps lies in the efficient way they | 0:30:14 | 0:30:18 | |

combine muscle, tendons and joints to harness the resilin's energy. | 0:30:18 | 0:30:23 | |

Only today do we know how a flea jumps and how high it can jump, | 0:30:26 | 0:30:32 | |

just as, in Hooke's time, a modern technology - a microscope - | 0:30:32 | 0:30:36 | |

enabled him to see the anatomy of the flea for the very first time, | 0:30:36 | 0:30:40 | |

so we have a camera now which is recording 5,000 images a second, | 0:30:40 | 0:30:46 | |

which will enable us to see how it jumps. | 0:30:46 | 0:30:49 | |

The camera is already running. | 0:30:49 | 0:30:51 | |

The flea is in that little box there | 0:30:51 | 0:30:55 | |

and we can see the image from the camera on this computer. | 0:30:55 | 0:30:59 | |

I will stop it as soon as I see that the flea has jumped. | 0:30:59 | 0:31:03 | |

There. | 0:31:06 | 0:31:07 | |

Its legs are already cocked in the jumping position, | 0:31:10 | 0:31:15 | |

and the cuticle, which is fused to the resilin, | 0:31:15 | 0:31:17 | |

is bent and ready to release its energy, | 0:31:17 | 0:31:20 | |

and then it lifts itself from the ground | 0:31:20 | 0:31:22 | |

and it's catapulted into the air. | 0:31:22 | 0:31:24 | |

Our story about fleas started 350 years ago | 0:31:28 | 0:31:32 | |

with Robert Hooke's first microscopic study. | 0:31:32 | 0:31:36 | |

Today, images from electron microscopes reveal even more details | 0:31:36 | 0:31:41 | |

than Hooke's beautiful drawings. | 0:31:41 | 0:31:43 | |

They show the rough hairs on the flea's shins and toes | 0:31:43 | 0:31:46 | |

that help it grip before thrusting itself into the air | 0:31:46 | 0:31:49 | |

with the final push from its toes. | 0:31:49 | 0:31:52 | |

So, can fleas jump 200 times their own body length? | 0:31:53 | 0:31:58 | |

It would seem not. | 0:31:58 | 0:32:00 | |

Nonetheless, they can leap | 0:32:00 | 0:32:02 | |

a respectable 38 times | 0:32:02 | 0:32:04 | |

the length of their bodies, which is not bad. | 0:32:04 | 0:32:07 | |

Fleas are extraordinarily strong | 0:32:09 | 0:32:13 | |

and we now know how they jump, | 0:32:13 | 0:32:16 | |

but the fleas' story isn't quite over. | 0:32:16 | 0:32:19 | |

A new discovery has added a twist to their lives | 0:32:19 | 0:32:22 | |

and dispelled another myth. | 0:32:22 | 0:32:24 | |

Recently, bodies of people who died of the Black Death | 0:32:25 | 0:32:29 | |

were uncovered by workers digging a new railway line. | 0:32:29 | 0:32:33 | |

Close inspection revealed that the Black Death was an airborne disease | 0:32:33 | 0:32:37 | |

and had nothing to do with rats or their fleas, | 0:32:37 | 0:32:42 | |

so the fleas' good name can at last be restored, and we can | 0:32:42 | 0:32:46 | |

celebrate them as one of the natural world's most spectacular jumpers. | 0:32:46 | 0:32:51 | |

A springy protein propels fleas with great force. | 0:32:52 | 0:32:56 | |

Next, we investigate another impossible feat - | 0:32:58 | 0:33:02 | |

the cheetah's legendary top speed of 70mph. | 0:33:02 | 0:33:06 | |

AEROPLANE ENGINE ROARS | 0:33:06 | 0:33:08 | |

Is this really possible? | 0:33:08 | 0:33:10 | |

CHEETAH PURRS | 0:33:12 | 0:33:14 | |

Cheetahs are beautiful, athletic-looking cats. | 0:33:14 | 0:33:19 | |

They've got the streamlined body, the small head, | 0:33:19 | 0:33:22 | |

elongated legs and narrow shoulders, | 0:33:22 | 0:33:25 | |

and a very long spine. | 0:33:25 | 0:33:27 | |

This looks like an animal that's built for speed, | 0:33:28 | 0:33:32 | |

but exactly how fast can he run? CHEETAH PURRS | 0:33:32 | 0:33:35 | |

They've been admired for their | 0:33:38 | 0:33:41 | |

grace and speed since antiquity. | 0:33:41 | 0:33:43 | |

The Egyptians were sometimes | 0:33:43 | 0:33:45 | |

buried with these cats because | 0:33:45 | 0:33:47 | |

they believed that they could hasten | 0:33:47 | 0:33:49 | |

the journey to the after-world | 0:33:49 | 0:33:52 | |

and, in more recent times, | 0:33:52 | 0:33:53 | |

sports hunters have used cheetahs to run down their prey. | 0:33:53 | 0:33:57 | |

So, the cheetah's impressive sprint has been known about for some time, | 0:34:01 | 0:34:07 | |

but where did the magical figure of 70mph come from? | 0:34:07 | 0:34:11 | |

Back in 1957, a cheetah hit the headlines, | 0:34:15 | 0:34:18 | |

with news of a rather unusual experiment. | 0:34:18 | 0:34:21 | |

A photographer called Kurt Severin | 0:34:30 | 0:34:32 | |

filmed and measured the running speed of a tame cheetah | 0:34:32 | 0:34:36 | |

using an upturned bicycle rather like this. | 0:34:36 | 0:34:40 | |

The back wheel was modified so that a strong fishing line could be | 0:34:40 | 0:34:44 | |

wound through the rim and pull along a meat-scented bag. | 0:34:44 | 0:34:49 | |

As the cheetah ran the 80-yard or 73-metre course | 0:34:49 | 0:34:53 | |

the pedals of the bike were hand-cranked | 0:34:53 | 0:34:54 | |

as fast as humanly possible | 0:34:54 | 0:34:56 | |

to drag the bag along just ahead of the cheetah. | 0:34:56 | 0:35:00 | |

The measurements were made manually using a stopwatch and a pistol. | 0:35:00 | 0:35:06 | |

Severin wrote that, | 0:35:06 | 0:35:07 | |

"From a deep crouch, the cheetah spurted to | 0:35:07 | 0:35:10 | |

"the end of the course in 2.25 seconds, | 0:35:10 | 0:35:13 | |

"for an average speed of 71mph." | 0:35:13 | 0:35:17 | |

And so, the legend was born. | 0:35:17 | 0:35:19 | |

BIRDS SCREECH | 0:35:19 | 0:35:22 | |

This impressive figure was immediately accepted | 0:35:22 | 0:35:25 | |

and is still often quoted today, | 0:35:25 | 0:35:27 | |

but how accurate is it? | 0:35:27 | 0:35:30 | |

The top speed of any running mammal depends on the power | 0:35:30 | 0:35:33 | |

of its muscles and the strength of its tendons and bones. | 0:35:33 | 0:35:36 | |

Human athletes train hard to reach their personal best | 0:35:39 | 0:35:43 | |

but there's still a limit to how fast they can run. | 0:35:43 | 0:35:46 | |

In a 100m sprint, a mere two seconds separates | 0:35:48 | 0:35:52 | |

a good amateur sprinter from a world-class champion. | 0:35:52 | 0:35:56 | |

The greyhound is similar in size and shape to a cheetah | 0:35:57 | 0:36:01 | |

so it's a good substitute animal to test out the cheetah's | 0:36:01 | 0:36:04 | |

legendary top speed of 70mph. | 0:36:04 | 0:36:07 | |

Their backs flex and extend so greatly that, | 0:36:12 | 0:36:15 | |

at times, none of their feet touch the ground... | 0:36:15 | 0:36:18 | |

..but when the greyhound's top speed was measured, | 0:36:22 | 0:36:25 | |

it was found to be 45mph - | 0:36:25 | 0:36:28 | |

a whole 25mph slower than the cheetah. | 0:36:28 | 0:36:31 | |

People argued that the cheetah could nonetheless achieve | 0:36:36 | 0:36:39 | |

a bigger stride because of extra flexibility in its back... | 0:36:39 | 0:36:43 | |

..but doubts about its top speed were beginning to creep in. | 0:36:47 | 0:36:50 | |

A new, more accurate way of testing was needed. | 0:36:50 | 0:36:54 | |

Here in the Royal Veterinary College, | 0:36:56 | 0:36:59 | |

they use dogs to help them in their studies of cheetahs. | 0:36:59 | 0:37:02 | |

Using a lurcher as a stand-in, | 0:37:02 | 0:37:05 | |

they've developed an extraordinary data-collecting collar. | 0:37:05 | 0:37:09 | |

It has a GPS attachment that will register position | 0:37:09 | 0:37:13 | |

to within a fraction of a metre. | 0:37:13 | 0:37:15 | |

It has movement sensors to show how the animal is, in fact, moving. | 0:37:15 | 0:37:20 | |

It can be remotely programmed | 0:37:20 | 0:37:22 | |

and it has a solar-charged battery that will last for up to a year. | 0:37:22 | 0:37:26 | |

The collars were tested and perfected on lurchers in Britain | 0:37:28 | 0:37:31 | |

to make sure that they were small and light enough | 0:37:31 | 0:37:34 | |

not to disturb their wearer. | 0:37:34 | 0:37:36 | |

Then, the collars were put on captive cheetahs, | 0:37:38 | 0:37:41 | |

to see if they could cope with the twisting run of the hunt. | 0:37:41 | 0:37:44 | |

The results were excellent, | 0:37:49 | 0:37:50 | |

and the collars were ready for the ultimate test... | 0:37:50 | 0:37:53 | |

in the wild. CHEETAH PANTS | 0:37:53 | 0:37:56 | |

FLIES BUZZ | 0:37:56 | 0:37:59 | |

Here was a chance to see if a wild cheetah's special adaptations | 0:37:59 | 0:38:03 | |

to hunting really enabled it to run at 70mph. | 0:38:03 | 0:38:08 | |

Wild cheetahs are faster than other, larger cats, like lions, | 0:38:10 | 0:38:14 | |

because of their lighter bones - | 0:38:14 | 0:38:16 | |

an advantage in a short, high-speed chase. | 0:38:16 | 0:38:19 | |

They have big nostrils, so they can take in large amounts of oxygen, | 0:38:21 | 0:38:26 | |

and an enlarged heart and lungs that increase circulation. | 0:38:26 | 0:38:30 | |

Their long tails act like rudders to help them steer | 0:38:33 | 0:38:36 | |

and assist their balance as they twist and turn. | 0:38:36 | 0:38:38 | |

BIRDS SCREECH | 0:38:38 | 0:38:40 | |

They need to be fast and manoeuvrable | 0:38:40 | 0:38:43 | |

because the prey they hunt is extremely agile | 0:38:43 | 0:38:46 | |

and able to change direction very quickly. | 0:38:46 | 0:38:49 | |

A cheetah can mirror such changes of movements in an instant. | 0:38:49 | 0:38:53 | |

But what would the GPS collars tell us about their speed? | 0:38:56 | 0:39:00 | |

Data from the collars has revealed fascinating details | 0:39:03 | 0:39:06 | |

about cheetahs' lives, | 0:39:06 | 0:39:08 | |

how they hunt and exactly how fast they can run. | 0:39:08 | 0:39:12 | |

The GPS measurements collected are accurate to within half a metre | 0:39:12 | 0:39:16 | |

and can be precisely matched to satellite images of the area, | 0:39:16 | 0:39:20 | |

so it's possible to see exactly what kind of terrain the cheetahs | 0:39:20 | 0:39:24 | |

were hunting on. | 0:39:24 | 0:39:25 | |

Here, we can see an 11-hour day in the life of a cheetah, | 0:39:25 | 0:39:29 | |

and there it starts to hunt. | 0:39:29 | 0:39:33 | |

The cheetah ran in one circular direction, | 0:39:33 | 0:39:38 | |

like this. | 0:39:38 | 0:39:40 | |

The blue represents deceleration, | 0:39:40 | 0:39:42 | |

getting slower here, | 0:39:42 | 0:39:44 | |

and there, at the red, where it gets faster and accelerates, | 0:39:44 | 0:39:48 | |

and the arrows represent the power of the force on the cheetah's body | 0:39:48 | 0:39:52 | |

as it swerves, and there, finally, | 0:39:52 | 0:39:55 | |

it made the kill. | 0:39:55 | 0:39:58 | |

367 hunts were studied | 0:39:58 | 0:40:01 | |

and the top speed of a chase was calculated to be 58mph. | 0:40:01 | 0:40:06 | |

BIRDS SCREECH | 0:40:06 | 0:40:09 | |

For more than half a century, | 0:40:13 | 0:40:15 | |

we have overestimated the cheetah's speed. | 0:40:15 | 0:40:18 | |

It is, nonetheless, still the fastest animal on land, | 0:40:20 | 0:40:24 | |

and its greatest feat is its acceleration - | 0:40:24 | 0:40:28 | |

four times that of Usain Bolt. | 0:40:28 | 0:40:31 | |

CHEETAH GROWLS | 0:40:35 | 0:40:37 | |

BIRDS SCREECH | 0:40:39 | 0:40:42 | |

CHEETAH SNARLS | 0:40:42 | 0:40:44 | |

The cheetah's legendary 70mph speed record is just a myth | 0:41:03 | 0:41:08 | |

but their true top speed of 58mph is still extraordinary. | 0:41:08 | 0:41:13 | |

A body that is fine-tuned for hunting helps them run in a really | 0:41:13 | 0:41:17 | |

remarkable way, but the cheetah's real impossible feat, so-called... | 0:41:17 | 0:41:23 | |

CHEETAH PURRS | 0:41:23 | 0:41:26 | |

..is the ability to change speeds so extremely quickly, | 0:41:28 | 0:41:32 | |

and that makes it one of the most manoeuvrable animals alive. | 0:41:32 | 0:41:36 | |

Aren't you? Aren't you? | 0:41:36 | 0:41:38 | |

CHEETAH PURRS | 0:41:38 | 0:41:40 | |

We may have overestimated the abilities of the flea | 0:41:42 | 0:41:45 | |

and the cheetah, but both exhibit remarkable feats of acceleration | 0:41:45 | 0:41:50 | |

in their quest for food - | 0:41:50 | 0:41:52 | |

the flea, to hop onto a passing host, | 0:41:52 | 0:41:55 | |

and the cheetah, to outmanoeuvre its prey. | 0:41:55 | 0:41:58 | |

BIRDS SCREECH | 0:41:58 | 0:42:01 |