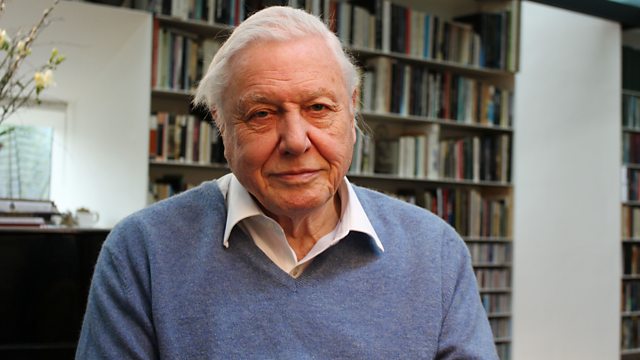

Episode 9 David Attenborough's Natural Curiosities

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Episode 9. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

The natural world is full of extraordinary animals with | 0:00:02 | 0:00:06 | |

amazing life histories. | 0:00:06 | 0:00:09 | |

Yet certain stories are more intriguing than most. | 0:00:09 | 0:00:12 | |

The mysteries of a butterfly's lifecycle, | 0:00:15 | 0:00:19 | |

or the strange biology of the Emperor penguin, | 0:00:19 | 0:00:23 | |

some of these creatures were surrounded by myth | 0:00:23 | 0:00:26 | |

and misunderstandings for a very long time. | 0:00:26 | 0:00:30 | |

And some have only recently revealed their secrets. | 0:00:30 | 0:00:34 | |

These are the animals that stand out from the crowd. | 0:00:34 | 0:00:38 | |

The curiosities I find most fascinating of all. | 0:00:38 | 0:00:42 | |

The bodies of some animals stretch and shrink in extraordinary ways. | 0:00:51 | 0:00:56 | |

Constrictor snakes can swallow prey twice their own size. | 0:00:57 | 0:01:02 | |

While the camel's hump can almost double in weight, | 0:01:02 | 0:01:06 | |

giving it the energy to travel huge distances across deserts. | 0:01:06 | 0:01:10 | |

What is the secret behind such expandable bodies? | 0:01:10 | 0:01:15 | |

Also in this programme, we meet two animals whose extraordinary | 0:01:20 | 0:01:24 | |

body shapes are determined by their diet. | 0:01:24 | 0:01:27 | |

The blue whale grows enormous | 0:01:27 | 0:01:29 | |

by feeding on tiny shrimp-like creatures, | 0:01:29 | 0:01:33 | |

while flamingos spend their lives eating with their heads upside down. | 0:01:33 | 0:01:38 | |

And yet, both ways are curiously similar. | 0:01:38 | 0:01:42 | |

We've long been fascinated by the camel's ability to live in the | 0:01:50 | 0:01:54 | |

harshest of deserts, places where during summer temperatures | 0:01:54 | 0:01:59 | |

can soar up to 50 degrees Celsius. | 0:01:59 | 0:02:02 | |

While in winter, they can drop to 30 degrees below freezing. | 0:02:02 | 0:02:07 | |

With little in the way of food or water, | 0:02:09 | 0:02:12 | |

camels can sometimes go without eating or drinking for over a week. | 0:02:12 | 0:02:17 | |

Most other animals couldn't survive conditions like this. | 0:02:18 | 0:02:22 | |

How does the camel do it? | 0:02:22 | 0:02:25 | |

The camel's secret was thought to lie in its hump. | 0:02:28 | 0:02:32 | |

In a healthy camel, it can be big and firm, like this one, and | 0:02:32 | 0:02:36 | |

weigh as much as 30 kilos, which is the weight of a ten-year-old child. | 0:02:36 | 0:02:40 | |

But if the camel goes without food, and particularly water, | 0:02:40 | 0:02:44 | |

for any length of time, then the hump can get floppy | 0:02:44 | 0:02:48 | |

and even droop over on one side, as that one has done. | 0:02:48 | 0:02:53 | |

So, people used to think that the camel stored water in its hump. | 0:02:53 | 0:02:58 | |

In fact, there are two different kinds of camel - the one hump, | 0:03:02 | 0:03:07 | |

or dromedary, and the two-humped, or the bactrian. | 0:03:07 | 0:03:12 | |

Nearly all camels alive today are the domesticated | 0:03:12 | 0:03:15 | |

descendants of one or the other. | 0:03:15 | 0:03:17 | |

The wild dromedary almost certainly doesn't exist. | 0:03:21 | 0:03:26 | |

And only a few bactrian camels remain, | 0:03:26 | 0:03:28 | |

roaming the deserts of central Asia. | 0:03:28 | 0:03:31 | |

The camel is a very tough animal, but in the wild today, | 0:03:31 | 0:03:36 | |

it's rarer than the giant panda. | 0:03:36 | 0:03:38 | |

It's hard to say where the idea of a water storing hump came from. | 0:03:41 | 0:03:45 | |

The Ancient Romans were the first to suggest that the | 0:03:45 | 0:03:49 | |

camel may have in a built-in water reservoir. | 0:03:49 | 0:03:52 | |

And then, later on, people got the idea that it had two stomachs - | 0:03:52 | 0:03:57 | |

one for food and one for water. | 0:03:57 | 0:03:59 | |

In the 18th century, an eminent anatomist, John Hunter, decided to | 0:04:01 | 0:04:06 | |

investigate the truth behind these assertions, | 0:04:06 | 0:04:09 | |

and he dissected a camel. | 0:04:09 | 0:04:11 | |

He found that the stomach consisted of three or four compartments, | 0:04:11 | 0:04:15 | |

similar to those of a cow or a sheep. | 0:04:15 | 0:04:18 | |

But inside one of those compartments, he discovered these | 0:04:18 | 0:04:22 | |

pocket-like structures, which are not found in any other large mammal. | 0:04:22 | 0:04:27 | |

Hunter didn't know what the pockets were for, but others after him | 0:04:27 | 0:04:31 | |

proposed that they were special water storage cells. | 0:04:31 | 0:04:35 | |

And then, despite any kind of evidence to prove that this | 0:04:35 | 0:04:39 | |

was true, for another 250 years, books on natural history, | 0:04:39 | 0:04:44 | |

like this one, featured illustrations of water | 0:04:44 | 0:04:48 | |

storage cells in the camel's stomach. | 0:04:48 | 0:04:50 | |

We now know that that's not true, even though | 0:04:52 | 0:04:55 | |

we don't know exactly what the strange pockets are for. | 0:04:55 | 0:04:59 | |

But the camel's hump is certainly not filled with water, | 0:04:59 | 0:05:03 | |

it's made entirely of fatty tissue. | 0:05:03 | 0:05:06 | |

It is, in fact, an energy reserve for times when food is scarce | 0:05:06 | 0:05:11 | |

and it can expand to such a degree that it makes | 0:05:11 | 0:05:14 | |

up 80% of the camel's body fat. | 0:05:14 | 0:05:17 | |

This enables a camel to go for two weeks without feeding, if necessary. | 0:05:17 | 0:05:23 | |

But there's a twist to the story. | 0:05:23 | 0:05:26 | |

When fat is broken down in the body, it produces not just energy, | 0:05:29 | 0:05:34 | |

but also water. | 0:05:34 | 0:05:36 | |

In fact, each gram of fat broken down during metabolism | 0:05:36 | 0:05:39 | |

produces one gram of water. | 0:05:39 | 0:05:42 | |

So could the camel's hump provide it with extra water after all? | 0:05:42 | 0:05:47 | |

A fatty hump that contains both food and water would seem to be | 0:05:49 | 0:05:53 | |

just what a desert animal needs, but it's not as simple as that. | 0:05:53 | 0:05:58 | |

To consume its fat, an animal needs more oxygen, | 0:05:58 | 0:06:03 | |

so it has to breathe more, so when living on the fat in its hump, | 0:06:03 | 0:06:07 | |

the camel actually loses more water through its airways than it gains. | 0:06:07 | 0:06:12 | |

So the camel doesn't have a secret store of water. | 0:06:12 | 0:06:18 | |

How then can it survive in a waterless desert? | 0:06:18 | 0:06:21 | |

Camels can go without drinking for more than a week | 0:06:21 | 0:06:25 | |

because they have an extraordinary ability to retain the body moisture. | 0:06:25 | 0:06:30 | |

We ourselves lose over a litre of water a day | 0:06:31 | 0:06:35 | |

through our moisture-laden breath. | 0:06:35 | 0:06:38 | |

But the camel has nostrils which it can shut tight. | 0:06:38 | 0:06:41 | |

And that not only keeps out the sand, | 0:06:41 | 0:06:44 | |

but retains the breath within the nose, and there, | 0:06:44 | 0:06:48 | |

the moisture can be reabsorbed by the linings of the nostrils. | 0:06:48 | 0:06:52 | |

Most mammals also lose a lot of water | 0:06:55 | 0:06:58 | |

when they cool their bodies by sweating. | 0:06:58 | 0:07:00 | |

But camels can endure a rise in body temperature that would kill | 0:07:03 | 0:07:08 | |

most other mammals without sweating. | 0:07:08 | 0:07:10 | |

If our temperature goes up by as little as one degree, it's a | 0:07:15 | 0:07:18 | |

sign of illness. | 0:07:18 | 0:07:20 | |

While three degrees causes vital organ damage and eventually, death. | 0:07:20 | 0:07:25 | |

The camel can cope with as much a six degree rise, | 0:07:27 | 0:07:31 | |

with no ill effect. | 0:07:31 | 0:07:33 | |

This means that camels don't have to sweat | 0:07:35 | 0:07:38 | |

until conditions get very hot indeed. | 0:07:38 | 0:07:40 | |

And if necessary, | 0:07:41 | 0:07:43 | |

they tolerate losing more of their body water than other mammals. | 0:07:43 | 0:07:47 | |

When animals become dehydrated, their blood becomes thicker | 0:07:49 | 0:07:53 | |

and more difficult to pump through the body. | 0:07:53 | 0:07:56 | |

If we lose 10% of our body water, we start to go dizzy and blind. | 0:07:56 | 0:08:00 | |

At 15%, our internal organs start to fail. | 0:08:00 | 0:08:05 | |

Camels however can lose a third of their body water with no ill | 0:08:05 | 0:08:09 | |

effect, something that would kill most other animals. | 0:08:09 | 0:08:13 | |

How do they do it? | 0:08:13 | 0:08:15 | |

Well, some of the answers may lie in the shape of their blood cells. | 0:08:15 | 0:08:20 | |

These are the red blood cells from a human being, | 0:08:20 | 0:08:24 | |

which are disc-shaped, like that of most mammals. | 0:08:24 | 0:08:28 | |

These, on the other hand, are from a camel | 0:08:28 | 0:08:32 | |

and are slimmer and more oval in shape. | 0:08:32 | 0:08:35 | |

It may be that the oval, streamlined shape makes it | 0:08:36 | 0:08:40 | |

easier for the blood to flow when the animal is dehydrated. | 0:08:40 | 0:08:43 | |

Certainly, a camel's blood is less thick and sticky than ours. | 0:08:45 | 0:08:50 | |

The cells also have particularly strong walls. | 0:08:50 | 0:08:55 | |

This prevents them from rupturing | 0:08:55 | 0:08:57 | |

when the animal suddenly drinks large amounts of water, and when | 0:08:57 | 0:09:01 | |

they do find water, camels have the ability to drink it very quickly. | 0:09:01 | 0:09:05 | |

A single camel can take the contents of all these bottles, | 0:09:07 | 0:09:10 | |

that's 100 litres, in a mere 10 minutes. | 0:09:10 | 0:09:14 | |

For any other animal to do that, it would be extremely dangerous, | 0:09:14 | 0:09:17 | |

but the camel has the ability to hold the water in the stomach | 0:09:17 | 0:09:21 | |

and only release it into the bloodstream very slowly, | 0:09:21 | 0:09:25 | |

in a way that does no damage. | 0:09:25 | 0:09:27 | |

We now understand how camels can survive harsh desert conditions. | 0:09:30 | 0:09:35 | |

And yet, surprisingly, new research suggests that they first have | 0:09:35 | 0:09:39 | |

evolved to live in the cold Arctic. | 0:09:39 | 0:09:42 | |

Scientists have recently discovered the fossil bones of giant shaggy | 0:09:44 | 0:09:49 | |

camels that roamed the forests of the Canadian Arctic | 0:09:49 | 0:09:53 | |

some 3.5 million years ago. | 0:09:53 | 0:09:55 | |

The Arctic camel was a third larger than the modern bactrian, | 0:09:57 | 0:10:01 | |

but otherwise looked very similar. | 0:10:01 | 0:10:04 | |

And that may be no coincidence. | 0:10:04 | 0:10:06 | |

The wide, flat feet that stop the camel from sinking into desert | 0:10:07 | 0:10:11 | |

sand could also have helped its ancestors walk in deep snow. | 0:10:11 | 0:10:16 | |

And a fatty hump provided the food reserve a camel would need to | 0:10:17 | 0:10:21 | |

survive long cold winters. | 0:10:21 | 0:10:23 | |

We may never fully understand the mysteries of the camel's hump, | 0:10:25 | 0:10:30 | |

whether it evolved first as a way of keeping warm or staying cool. | 0:10:30 | 0:10:35 | |

But we have unravelled many other mysteries of the animal's | 0:10:35 | 0:10:39 | |

body that enable it to endure conditions that few other | 0:10:39 | 0:10:42 | |

animals would be able to withstand. | 0:10:42 | 0:10:45 | |

The camel's expandable hump was a mystery to us for centuries. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:51 | |

Our second curiosity can stretch its body in even more | 0:10:51 | 0:10:56 | |

extraordinary ways and devour prey many times its own size. | 0:10:56 | 0:11:00 | |

This is a green anaconda, one of the largest snakes in the world. | 0:11:02 | 0:11:07 | |

It's about four metres long and weighs 70 kilos, | 0:11:07 | 0:11:12 | |

and it's only half grown. | 0:11:12 | 0:11:14 | |

They can grow to a length of six metres | 0:11:14 | 0:11:16 | |

and weigh twice as much as this one. | 0:11:16 | 0:11:19 | |

But it's their ability to be able to swallow enormous prey that's | 0:11:19 | 0:11:24 | |

really grabbed our imagination. | 0:11:24 | 0:11:26 | |

Could one of these really bite a man | 0:11:26 | 0:11:30 | |

and swallow him whole and alive? | 0:11:30 | 0:11:33 | |

In the 16th century, European explorers venturing in to the | 0:11:35 | 0:11:39 | |

Amazon jungle were fascinated by tales of a huge river monster. | 0:11:39 | 0:11:43 | |

It was said to devour cattle and deer and to spit out | 0:11:45 | 0:11:49 | |

water like shot from a cannon, knocking animals out of trees. | 0:11:49 | 0:11:52 | |

These fantastic stories led people to go in search of this | 0:11:54 | 0:11:58 | |

marvellous beast. | 0:11:58 | 0:12:01 | |

In 1907, a British explorer, Colonel Percy Fawcett, | 0:12:01 | 0:12:07 | |

claimed to have encountered an enormous snake on the Amazon River. | 0:12:07 | 0:12:13 | |

A huge head, he said, rose up from the water, | 0:12:13 | 0:12:16 | |

dangerously close to his canoe, and a colossal anaconda emerged. | 0:12:16 | 0:12:22 | |

Greatly alarmed, he shot the snake dead. | 0:12:22 | 0:12:26 | |

He claimed that when measured, it proved to be nearly 19 metres, | 0:12:26 | 0:12:31 | |

over 60ft, long. | 0:12:31 | 0:12:33 | |

But Fawcett's account was met with disbelief and he never provided | 0:12:33 | 0:12:39 | |

convincing proof because soon after that, he | 0:12:39 | 0:12:42 | |

vanished into the Brazilian jungle and was never seen again. | 0:12:42 | 0:12:46 | |

The creature that Fawcett encountered was almost | 0:12:48 | 0:12:51 | |

certainly a green anaconda. | 0:12:51 | 0:12:54 | |

Despite their massive proportions, | 0:12:54 | 0:12:57 | |

these huge snakes are seldom seen because they spend | 0:12:57 | 0:13:00 | |

most of their time in water, waiting in ambush for their prey. | 0:13:00 | 0:13:04 | |

In this murky world, they're certainly well camouflaged | 0:13:07 | 0:13:11 | |

and so some people believed that somewhere, | 0:13:11 | 0:13:14 | |

another real monster might still be lurking unseen. | 0:13:14 | 0:13:18 | |

In the 1960s, a snake was brought to the | 0:13:23 | 0:13:26 | |

Museum Of Zoology at the University College London. | 0:13:26 | 0:13:29 | |

This is it. | 0:13:29 | 0:13:31 | |

It had lived in London Zoo for some years before it died | 0:13:31 | 0:13:34 | |

and it was five metres long. | 0:13:34 | 0:13:37 | |

A lot of work went into preparing the skeleton. | 0:13:37 | 0:13:39 | |

It had to be carried out on to the flat roof of the museum | 0:13:39 | 0:13:43 | |

and it was finally displayed in this rather unusual way - | 0:13:43 | 0:13:47 | |

wrapped around the branch of a tree. | 0:13:47 | 0:13:50 | |

For years, the museum displayed it as an anaconda, | 0:13:53 | 0:13:58 | |

but in 2012, | 0:13:58 | 0:14:00 | |

a member of the public saw an old photo of the snake | 0:14:00 | 0:14:03 | |

on the museum's website and pointed out that it | 0:14:03 | 0:14:06 | |

looked like an African rock python and not an anaconda. | 0:14:06 | 0:14:10 | |

It's unclear how the mistake came about. | 0:14:10 | 0:14:14 | |

The markings on the two snakes are quite different. | 0:14:14 | 0:14:17 | |

But both are giants and there's much controversy as to which | 0:14:17 | 0:14:21 | |

species is the largest snake of all. | 0:14:21 | 0:14:23 | |

Anacondas, pythons, and boas, like this one, don't kill with venom. | 0:14:25 | 0:14:30 | |

They're constrictors. They squeeze their prey to death. | 0:14:30 | 0:14:35 | |

And their coils can exert a very strong pressure indeed, | 0:14:35 | 0:14:38 | |

as I can feel with this one on my arm. | 0:14:38 | 0:14:42 | |

But a big anaconda can squeeze with the force of around 4,000 kilos, | 0:14:42 | 0:14:47 | |

that's like having a bus on your chest. | 0:14:47 | 0:14:51 | |

And that can certainly crush the spine of a deer or a capybara. | 0:14:51 | 0:14:55 | |

And yet, constrictor snakes don't usually crush their prey. | 0:14:58 | 0:15:03 | |

In most cases, they simply squeeze it | 0:15:03 | 0:15:05 | |

so hard that the animal can't breathe. | 0:15:05 | 0:15:09 | |

Every time its prey tries to inhale, | 0:15:09 | 0:15:12 | |

the snake's powerful muscles squeeze harder. | 0:15:12 | 0:15:16 | |

The unfortunate victim then either dies | 0:15:16 | 0:15:19 | |

because its blood can no longer circulate, or suffocates. | 0:15:19 | 0:15:22 | |

An anaconda, or a python, can kill prey that is not only | 0:15:33 | 0:15:37 | |

twice its own body size, but many times bigger than its head. | 0:15:37 | 0:15:42 | |

So how does it manage to swallow its victim whole? | 0:15:42 | 0:15:45 | |

Popular folklore has it that anacondas | 0:15:49 | 0:15:53 | |

and pythons unhinge or dislocate their jaws to swallow large prey. | 0:15:53 | 0:15:59 | |

That is not true. | 0:15:59 | 0:16:01 | |

They do, however, have the ability to open their mouths wider than | 0:16:01 | 0:16:05 | |

most animals. | 0:16:05 | 0:16:07 | |

Pythons and anacondas have this additional bone | 0:16:07 | 0:16:11 | |

attached to the back of their jaws. | 0:16:11 | 0:16:14 | |

This provides a double hinge at the joint and allows them | 0:16:14 | 0:16:18 | |

to open their jaws extremely wide, both downwards and sideways. | 0:16:18 | 0:16:25 | |

In addition, the two sides of the lower jaw are not fused | 0:16:25 | 0:16:29 | |

together, but joined by an elastic ligament. | 0:16:29 | 0:16:33 | |

This gives the jaws a lot of stretch and they can even move apart | 0:16:33 | 0:16:38 | |

when the snake is swallowing large prey. | 0:16:38 | 0:16:41 | |

It also allows each side of the jaw to move independently of the other. | 0:16:41 | 0:16:46 | |

When eating a meal, | 0:16:46 | 0:16:49 | |

particularly one that is much larger than itself, | 0:16:49 | 0:16:52 | |

the snake can alternately move its jaws on either side of its head | 0:16:52 | 0:16:57 | |

and walk its prey into its mouth, | 0:16:57 | 0:17:00 | |

even while its victim is still alive. | 0:17:00 | 0:17:03 | |

As the jaws open wide, the snake's elastic skin stretches. | 0:17:05 | 0:17:11 | |

But the mobility of the skull comes with a price. | 0:17:11 | 0:17:15 | |

Many of the joints that in other snakes are solid have been | 0:17:15 | 0:17:19 | |

replaced by mobile ones. | 0:17:19 | 0:17:22 | |

So the skull has less crushing power. | 0:17:22 | 0:17:25 | |

As a consequence, | 0:17:25 | 0:17:27 | |

the snake has to use its entire body to overpower its prey. | 0:17:27 | 0:17:31 | |

Getting large prey into the mouth is one problem, but how does the snake | 0:17:36 | 0:17:41 | |

push it all the way down the length of its body, into its stomach? | 0:17:41 | 0:17:44 | |

This is a Burmese python and it hasn't fed for a long time. | 0:17:47 | 0:17:53 | |

So I'm hoping to give it a little breakfast. | 0:17:53 | 0:17:56 | |

With a dead rat. | 0:17:56 | 0:17:59 | |

What about that? | 0:17:59 | 0:18:01 | |

Saliva from the salivary glands in the mouth has moistened | 0:18:12 | 0:18:16 | |

the prey, so it's easier to swallow. | 0:18:16 | 0:18:19 | |

And now, it's moving its jaws, | 0:18:19 | 0:18:22 | |

drawing the rat farther down its throat, | 0:18:22 | 0:18:26 | |

until eventually the muscles of the flanks take over, | 0:18:26 | 0:18:28 | |

squeezing the prey and pushing against the ribs, so that it | 0:18:28 | 0:18:33 | |

looks as though the snake is, as it were, crawling around the rat. | 0:18:33 | 0:18:38 | |

And that will continue for some time, | 0:18:41 | 0:18:44 | |

as the prey is worked down, in to the snake's body, until | 0:18:44 | 0:18:49 | |

eventually it reaches the stomach, which is around the middle here. | 0:18:49 | 0:18:53 | |

Equally remarkable is what happens inside the snake. | 0:19:00 | 0:19:04 | |

After months of fasting, | 0:19:04 | 0:19:08 | |

it has to restart its digestive system quickly. | 0:19:08 | 0:19:11 | |

Within a day, some of the internal organs double in size. | 0:19:13 | 0:19:17 | |

The heart expands, | 0:19:17 | 0:19:20 | |

pumping greater volumes of blood around the body | 0:19:20 | 0:19:23 | |

and special cells in the lining of the stomach produce powerful | 0:19:23 | 0:19:27 | |

enzymes that break down flesh and bones. | 0:19:27 | 0:19:30 | |

And when the prey is entirely digested, | 0:19:34 | 0:19:37 | |

the python's organs return to normal again. | 0:19:37 | 0:19:40 | |

Anacondas and pythons are able to take in enormous | 0:19:44 | 0:19:48 | |

meals in a single mouthful. | 0:19:48 | 0:19:49 | |

But how do they then survive fasting for months on end? | 0:19:52 | 0:19:55 | |

Like all coldblooded animals, | 0:19:59 | 0:20:01 | |

snakes get much of their heat from the sun, | 0:20:01 | 0:20:03 | |

so they need less food to fuel their bodies | 0:20:03 | 0:20:07 | |

and most of what they eat is converted directly into body mass. | 0:20:07 | 0:20:11 | |

Snakes continue to grow throughout their lives and anacondas get | 0:20:13 | 0:20:18 | |

bigger than any other species because they live mostly in water. | 0:20:18 | 0:20:23 | |

Their massive body is supported by its buoyancy. | 0:20:23 | 0:20:26 | |

So it's certainly possible that an anaconda could grow to | 0:20:29 | 0:20:33 | |

an enormous size. | 0:20:33 | 0:20:34 | |

But how large can a snake really get? | 0:20:36 | 0:20:40 | |

In 2009, further light was shed on this question with | 0:20:44 | 0:20:48 | |

the discovery of the fossils of a super snake. | 0:20:48 | 0:20:52 | |

It was given the name titanoboa | 0:20:52 | 0:20:54 | |

and it suggests that snakes can get very large indeed. | 0:20:54 | 0:20:58 | |

Titanoboa was nearly 13 metres long, the length of a bus, | 0:20:59 | 0:21:04 | |

and must have weighed over a tonne. | 0:21:04 | 0:21:06 | |

It lived around 60 million years ago, | 0:21:06 | 0:21:08 | |

shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs. | 0:21:08 | 0:21:12 | |

We don't know for sure, | 0:21:12 | 0:21:13 | |

but it may be that the warmer climate of the Earth | 0:21:13 | 0:21:15 | |

at the time allowed coldblooded snakes to grow much larger in size. | 0:21:15 | 0:21:20 | |

What is certain is that for at least 10 million years, | 0:21:20 | 0:21:25 | |

titanoboa was the largest predator on the planet. | 0:21:25 | 0:21:28 | |

Both the camel | 0:21:32 | 0:21:33 | |

and the anaconda can withstand extreme periods of fasting, | 0:21:33 | 0:21:38 | |

but it's only by looking inside the camel's hump | 0:21:38 | 0:21:42 | |

and the anaconda's stomach that we've discovered | 0:21:42 | 0:21:45 | |

the truth behind their amazing expandable bodies. | 0:21:45 | 0:21:49 | |

The blue whale weighs almost 200 tonnes. | 0:21:56 | 0:22:00 | |

It's the largest animal on Earth and it's rarely seen. | 0:22:00 | 0:22:03 | |

I didn't glimpse one until I had been filming animals for almost | 0:22:03 | 0:22:08 | |

50 years and when I did, it was one of the greatest thrills of my life. | 0:22:08 | 0:22:12 | |

I can see its tail, just under my boat here. | 0:22:21 | 0:22:24 | |

And it's coming up... It's coming up... | 0:22:24 | 0:22:27 | |

There! | 0:22:27 | 0:22:28 | |

The blue whale is 100ft long. | 0:22:28 | 0:22:34 | |

30 metres. | 0:22:34 | 0:22:35 | |

Nothing like that can grow on land | 0:22:37 | 0:22:40 | |

because no bone is solid enough to support such bulk. | 0:22:40 | 0:22:43 | |

Only in the sea can you get such | 0:22:44 | 0:22:47 | |

huge size as that magnificent creature. | 0:22:47 | 0:22:51 | |

The blue whale was a mystery to science for a long time. | 0:23:10 | 0:23:14 | |

Living out in the deep oceans, | 0:23:14 | 0:23:16 | |

people rarely caught sight of more than the spout of this giant. | 0:23:16 | 0:23:20 | |

The first published description comes from a physician, Robert | 0:23:20 | 0:23:25 | |

Sibbald, who found a whale stranded off the coast of Scotland in 1692. | 0:23:25 | 0:23:31 | |

It was first named after Sibbald, | 0:23:31 | 0:23:34 | |

but later given the scientific name Balaenoptera musculus. | 0:23:34 | 0:23:39 | |

the Latin "musculus" means both muscle and little mouse, | 0:23:39 | 0:23:44 | |

an ironic double meaning for the largest animal on Earth. | 0:23:44 | 0:23:48 | |

When the first blue whale specimens were washed up on our shores, | 0:23:51 | 0:23:55 | |

they must have caused quite a stir and excitement. | 0:23:55 | 0:23:59 | |

Here was a colossal animal, weighing over 150 tonnes, | 0:23:59 | 0:24:02 | |

nothing as big had even been seen before. | 0:24:02 | 0:24:06 | |

A giant of this scale must be a predator, | 0:24:06 | 0:24:09 | |

at the top of the food chain. | 0:24:09 | 0:24:11 | |

But what kind of creature was it? | 0:24:11 | 0:24:14 | |

And what was it feeding on to make it so big? | 0:24:14 | 0:24:16 | |

The first blue whale specimens were found at a time | 0:24:19 | 0:24:23 | |

when scientists were just starting to classify animals, not | 0:24:23 | 0:24:26 | |

only by their external appearance, but by their internal structures. | 0:24:26 | 0:24:30 | |

And few animals proved as problematic as the whales. | 0:24:31 | 0:24:35 | |

From the outside, they looked and behaved like fish, | 0:24:37 | 0:24:40 | |

but their internal organs were like those of a large mammal. | 0:24:40 | 0:24:44 | |

The bones of the whale's front fins are very similar to | 0:24:47 | 0:24:50 | |

those in our own arms. | 0:24:50 | 0:24:53 | |

The five digits on the hand are clearly visible. | 0:24:53 | 0:24:56 | |

But they've been modified in to paddles for swimming. | 0:24:56 | 0:24:59 | |

What kind of creatures were these truly extraordinary animals? | 0:25:03 | 0:25:07 | |

The controversy as to whether whales were fish or mammals came to | 0:25:11 | 0:25:15 | |

a head in a New York courtroom in 1818. | 0:25:15 | 0:25:18 | |

A jury was asked to pass | 0:25:18 | 0:25:20 | |

judgement on the question for the purpose of the New York state law. | 0:25:20 | 0:25:25 | |

The issue had come up because a shrewd merchant who owned three | 0:25:25 | 0:25:28 | |

barrels of whale oil had refused to pay tax levied on fish oil. | 0:25:28 | 0:25:33 | |

He pointed out that, according to the latest scientific opinion, | 0:25:33 | 0:25:37 | |

whales weren't in fact fish. | 0:25:37 | 0:25:39 | |

The inspector collecting the tax had scorned the idea. "What?! | 0:25:39 | 0:25:43 | |

"Whales not fish?!" he said. | 0:25:43 | 0:25:45 | |

And slapped handcuffs on the merchant. | 0:25:45 | 0:25:47 | |

The lead witness was a respected scientist called Samuel Mitchell. | 0:25:49 | 0:25:54 | |

Mitchell entered the courtroom expecting to explain to | 0:25:54 | 0:25:57 | |

everybody why whales were mammals, not fish, | 0:25:57 | 0:26:01 | |

but instead, found himself being attacked by the most gifted | 0:26:01 | 0:26:05 | |

lawyer in the country, William Sampson. | 0:26:05 | 0:26:07 | |

Sampson argued that scientists didn't have the right to | 0:26:09 | 0:26:12 | |

rename God's creatures and force them in to absurd groupings. | 0:26:12 | 0:26:16 | |

The idea that humans | 0:26:18 | 0:26:19 | |

and whales should be in the same category seemed to him grotesque. | 0:26:19 | 0:26:23 | |

Mitchell and science never stood a chance. | 0:26:26 | 0:26:30 | |

After deliberating for 15 minutes, the jury announced | 0:26:30 | 0:26:33 | |

the verdict in favour of Sampson and the fish oil inspector. | 0:26:33 | 0:26:37 | |

According to New York state law, whales were deemed to be fish, | 0:26:37 | 0:26:41 | |

not mammals. | 0:26:41 | 0:26:44 | |

Although the general public still considered whales to be fish, | 0:26:46 | 0:26:49 | |

scientists were by now largely agreed that they were indeed | 0:26:49 | 0:26:53 | |

mammals that had taken to living in the sea. | 0:26:53 | 0:26:56 | |

But what was the blue whale feeding on to allow it to grow to | 0:26:59 | 0:27:03 | |

such an extraordinary size? | 0:27:03 | 0:27:04 | |

The answer can be found by looking inside the mouth, | 0:27:06 | 0:27:09 | |

which contains some very bizarre looking structures. | 0:27:09 | 0:27:12 | |

This is the skeleton of a right whale | 0:27:15 | 0:27:18 | |

and its mouth parts are very similar to those of the blue whale. | 0:27:18 | 0:27:22 | |

Instead of teeth, it has these strange plate-like structures | 0:27:22 | 0:27:26 | |

hanging from the upper jaw. | 0:27:26 | 0:27:28 | |

The plates are aligned alongside each other and the inner | 0:27:28 | 0:27:32 | |

edges fray because the large tongue continually rubs up against them. | 0:27:32 | 0:27:37 | |

And then, the frayed edges entangle to form a thick mat that | 0:27:37 | 0:27:42 | |

acts like a gigantic sieve. | 0:27:42 | 0:27:44 | |

And when early naturalists opened up the gigantic gut of these whales, | 0:27:45 | 0:27:49 | |

they found not fish or other large prey, | 0:27:49 | 0:27:52 | |

but tiny shrimp-like creatures called krill. | 0:27:52 | 0:27:56 | |

To everyone's astonishment, | 0:27:56 | 0:27:58 | |

it turned out that these whales feed on some of the smallest | 0:27:58 | 0:28:01 | |

prey in the sea and these strange plates serve to filter | 0:28:01 | 0:28:07 | |

the krill out of the water. | 0:28:07 | 0:28:08 | |

The rows of plates are called baleen and we now know that they | 0:28:11 | 0:28:15 | |

form a highly specialised filter feeding system. | 0:28:15 | 0:28:18 | |

The giant animal dives deep beneath the surface, | 0:28:21 | 0:28:24 | |

in search of swarms of krill. | 0:28:24 | 0:28:26 | |

The pleated skin on the throat | 0:28:28 | 0:28:30 | |

and belly expand and the mouth balloons outward to four | 0:28:30 | 0:28:34 | |

times the size, taking in an enormous mouthful of water. | 0:28:34 | 0:28:38 | |

The tongue then forces the water out through the baleen | 0:28:43 | 0:28:46 | |

and thousands of tiny krill are left behind. | 0:28:46 | 0:28:49 | |

Today, we know a lot more about this unusual feeding structure. | 0:28:52 | 0:28:56 | |

This is baleen. | 0:28:58 | 0:29:02 | |

It's often referred to as whale bone, but it's not bone at all. | 0:29:02 | 0:29:06 | |

It's keratin, the same substance as our hair and fingernails. | 0:29:06 | 0:29:10 | |

And it's both strong and slightly elastic. | 0:29:10 | 0:29:14 | |

The plates emerge from the whale's jaws instead of teeth | 0:29:14 | 0:29:17 | |

and continue to grow throughout the whale's lifetime. | 0:29:17 | 0:29:21 | |

These bands in it are much like the rings of a tree. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:24 | |

Several may be laid down in the course of a year, | 0:29:24 | 0:29:27 | |

so the baleen can give us an indication of the age of a whale. | 0:29:27 | 0:29:31 | |

We also know from other evidence that blue whales can live to | 0:29:31 | 0:29:34 | |

be over 100 years old. | 0:29:34 | 0:29:36 | |

Recently discovered fossil whales have both teeth and simple filters, | 0:29:39 | 0:29:44 | |

which suggest that early filter feeding whales may have | 0:29:44 | 0:29:48 | |

sucked small animals from the sea floor. | 0:29:48 | 0:29:50 | |

There is a whale alive today that feeds in just that way, | 0:29:52 | 0:29:57 | |

the grey whale. | 0:29:57 | 0:29:58 | |

It stirs up the sediment and scoops it in to its mouth | 0:29:58 | 0:30:03 | |

and then filters out small food particles with its baleen. | 0:30:03 | 0:30:06 | |

Krill is abundant in the oceans | 0:30:16 | 0:30:19 | |

and blue whales can eat enormous quantities of it with each mouthful, | 0:30:19 | 0:30:24 | |

soon swallowing 90 times more than they immediately need. | 0:30:24 | 0:30:28 | |

The surplus is then stored in the form of blubber | 0:30:28 | 0:30:32 | |

and this helps them cope with periods when food is scarce. | 0:30:32 | 0:30:36 | |

The blue whale was a mystery to us for a long time. | 0:30:40 | 0:30:44 | |

But we now know that its enormous body is fuelled with vast | 0:30:44 | 0:30:48 | |

quantities of the tiniest of prey. Over the course of its lifetime, | 0:30:48 | 0:30:53 | |

a blue whale will consume around 50,000 tonnes of krill | 0:30:53 | 0:30:59 | |

and unlike teeth, which fall out with old age, | 0:30:59 | 0:31:02 | |

the baleen never stops growing and is constantly replaced. | 0:31:02 | 0:31:06 | |

Maybe this unusual body design not only helps the blue whale | 0:31:06 | 0:31:10 | |

grow to this enormous size, but also to such a formidable old age. | 0:31:10 | 0:31:16 | |

The blue whale has become a giant by filtering tiny creatures | 0:31:17 | 0:31:21 | |

out of the ocean. | 0:31:21 | 0:31:23 | |

Our second curiosity, the flamingo, | 0:31:24 | 0:31:27 | |

also has an unusual body that has been shaped by its diet. | 0:31:27 | 0:31:31 | |

For a long time, the flamingos were birds of myth and mystery. | 0:31:35 | 0:31:40 | |

Travellers in Africa saw them shrouded by the hazy mists, | 0:31:40 | 0:31:44 | |

rising from volcanic soda lakes and believed that they were firebirds. | 0:31:44 | 0:31:49 | |

In Egyptian mythology, the firebird, or phoenix, | 0:31:51 | 0:31:54 | |

was a sacred creature with beautiful red plumage that was | 0:31:54 | 0:31:58 | |

consumed by magical fire and then rose again from its own ashes. | 0:31:58 | 0:32:03 | |

The flamingo's scientific name, Phoenicopterus, | 0:32:05 | 0:32:08 | |

reflects some of its legendary past. | 0:32:08 | 0:32:11 | |

It means phoenix wing. | 0:32:11 | 0:32:14 | |

These beautiful | 0:32:14 | 0:32:15 | |

and elegant creatures are some of the most curious looking of birds. | 0:32:15 | 0:32:20 | |

No other bird has a beak shaped quite like this. | 0:32:20 | 0:32:24 | |

Or indeed such glorious pink colours. | 0:32:24 | 0:32:27 | |

And yet, we're so familiar with them that we | 0:32:27 | 0:32:29 | |

rarely think about their strange appearance. | 0:32:29 | 0:32:33 | |

Why is it that the flamingo is so different from all other birds? | 0:32:33 | 0:32:37 | |

In that classic children's book, | 0:32:39 | 0:32:41 | |

Alice In Wonderland, Lewis Carroll has fun with the flamingo's oddity. | 0:32:41 | 0:32:46 | |

Alice plays croquet with the Red Queen, using them as mallets, | 0:32:48 | 0:32:52 | |

holding their heads and necks upside down, | 0:32:52 | 0:32:55 | |

in much the same posture as the birds take when feeding. | 0:32:55 | 0:32:59 | |

When you look at the skeleton of a flamingo, the thing that strikes | 0:33:02 | 0:33:06 | |

you most is the extraordinary length of the legs and the neck. | 0:33:06 | 0:33:11 | |

The neck has 17 bones in it, | 0:33:11 | 0:33:14 | |

which is no more than in other birds, but each is greatly | 0:33:14 | 0:33:18 | |

elongated, giving the flamingo its extra long neck and flexibility. | 0:33:18 | 0:33:24 | |

But the flamingo's most curious feature is surely its beak. | 0:33:24 | 0:33:28 | |

And the reason it looks | 0:33:28 | 0:33:30 | |

so strange is that it is the only beak adapted for use upside down. | 0:33:30 | 0:33:36 | |

In most birds, the upper part of the bill is larger than the lower | 0:33:36 | 0:33:41 | |

one, but in the flamingo's, it's the other way round. | 0:33:41 | 0:33:45 | |

The lower bill is much bigger | 0:33:45 | 0:33:47 | |

and has a deep central groove in it that holds the flamingo's tongue. | 0:33:47 | 0:33:51 | |

The upper jaw is thin and moveable, so when the bird's head is | 0:33:53 | 0:33:59 | |

upside down, the flamingo's jaws work, as it were, normally. | 0:33:59 | 0:34:05 | |

When feeding, the flamingo gently sweeps its bill back and forth, | 0:34:10 | 0:34:15 | |

sucking water in at the front and squirting it out from the sides. | 0:34:15 | 0:34:19 | |

The water that goes in is murky, while that which flows out is | 0:34:26 | 0:34:30 | |

clear and that gives us a clue to what it's feeding on. | 0:34:30 | 0:34:34 | |

The beak has tiny bristles all along its edges, | 0:34:38 | 0:34:42 | |

much like the whale's baleen. | 0:34:42 | 0:34:43 | |

And the tongue has two rows of horny spikes along its length. | 0:34:47 | 0:34:51 | |

When feeding, the bristles and spikes form a sieve, | 0:34:56 | 0:34:59 | |

trapping any particles inside. | 0:34:59 | 0:35:01 | |

And the large tongue acts as a pump, pushing water in and out. | 0:35:04 | 0:35:09 | |

It's a unique design for a beak. No other bird has one like it. | 0:35:12 | 0:35:17 | |

Although at first sight, they may look the same, | 0:35:21 | 0:35:25 | |

flamingo beaks in fact come in two different shapes. | 0:35:25 | 0:35:28 | |

This is because they eat slightly different food. | 0:35:29 | 0:35:32 | |

This is the beak of a greater flamingo, | 0:35:35 | 0:35:39 | |

which feeds on crustaceans, | 0:35:39 | 0:35:41 | |

which are usually found near the bottom of a lake. | 0:35:41 | 0:35:45 | |

It's long and shallow, | 0:35:45 | 0:35:47 | |

so the birds can feed in water only a few millimetres deep. | 0:35:47 | 0:35:50 | |

This beak, on the other hand, is from a lesser flamingo. | 0:35:52 | 0:35:56 | |

Its bill is shorter, but more bulbous and deep-keeled. | 0:35:56 | 0:36:00 | |

The lesser flamingo feeds on microscopic algae, | 0:36:00 | 0:36:05 | |

which usually float just below the surface of the water, | 0:36:05 | 0:36:08 | |

and the deep keel acts as a buoy, bobbing along just at the | 0:36:08 | 0:36:13 | |

right depth, as the bird moves through the water. | 0:36:13 | 0:36:16 | |

These different bills allow two species of flamingo to live | 0:36:21 | 0:36:25 | |

side by side. | 0:36:25 | 0:36:26 | |

In Africa's Rift Valley, greater and lesser flamingos are found on | 0:36:28 | 0:36:33 | |

the soda lakes, having specialised on food that others can't reach. | 0:36:33 | 0:36:38 | |

The waters are so hot and toxic that they would strip | 0:36:41 | 0:36:44 | |

the flesh off any other animal, but flamingos thrive here. | 0:36:44 | 0:36:48 | |

Their long spindly legs have tough scales | 0:36:53 | 0:36:56 | |

and their webbed feet prevent them from sinking in to the soft mud. | 0:36:56 | 0:37:00 | |

The birds can even drink the water, which is | 0:37:02 | 0:37:05 | |

two or three times saltier than the ocean. | 0:37:05 | 0:37:07 | |

But it's not just the mud and water which are poisonous. | 0:37:11 | 0:37:14 | |

The blue green algae, which many of them feed on, | 0:37:16 | 0:37:19 | |

actually contain nasty toxic chemicals. | 0:37:19 | 0:37:23 | |

If that were to accumulate in the internal organs of the bird, | 0:37:23 | 0:37:27 | |

they could be lethal. | 0:37:27 | 0:37:28 | |

But the flamingo deals with that by directing these | 0:37:28 | 0:37:31 | |

chemicals into the feathers and the skin, where they do no damage. | 0:37:31 | 0:37:36 | |

The feathers of flamingos contain very high concentrations | 0:37:37 | 0:37:40 | |

of toxins, but they also contain another chemical, carotene. | 0:37:40 | 0:37:46 | |

Carotene is the reddish pigment that gives | 0:37:46 | 0:37:50 | |

flamingos their distinctive pink colour. | 0:37:50 | 0:37:53 | |

And it also comes from their diet. But carotene is not harmful. | 0:37:53 | 0:37:57 | |

On the contrary, it's a source of vitamin | 0:37:57 | 0:38:00 | |

and boosts the immune system, protecting against illness, | 0:38:00 | 0:38:05 | |

so a pink bird is also a healthy bird. | 0:38:05 | 0:38:08 | |

This glorious pink colour was probably an incidental | 0:38:13 | 0:38:17 | |

by-product of their diet. | 0:38:17 | 0:38:19 | |

Nonetheless over time, | 0:38:19 | 0:38:21 | |

it's evolved to play an important role in the flamingo's social life. | 0:38:21 | 0:38:26 | |

The flashes of colour are an integral part of their | 0:38:26 | 0:38:29 | |

courtship display and recent research has shown that the pinkest | 0:38:29 | 0:38:34 | |

flamingos are the most popular when it comes to finding a mate. | 0:38:34 | 0:38:38 | |

When flamingos breed, much of the carotene in their diet gets | 0:38:43 | 0:38:48 | |

channelled into the developing young. | 0:38:48 | 0:38:50 | |

Even the eggs receive pigments. | 0:38:50 | 0:38:53 | |

So much, in fact, that the yolk can be virtually blood red in colour. | 0:38:53 | 0:38:58 | |

These eggs are from captive flamingos and are infertile. | 0:38:58 | 0:39:03 | |

Let's have a look. | 0:39:03 | 0:39:05 | |

There. | 0:39:06 | 0:39:07 | |

Well, it's nothing like the colour or any other bird yolk that | 0:39:10 | 0:39:14 | |

I've ever seen. | 0:39:14 | 0:39:17 | |

Flamingos are so efficient at collecting their specialised | 0:39:17 | 0:39:20 | |

food that the yolk is actually packed full of protein and fat. | 0:39:20 | 0:39:24 | |

And this allows the chick to grow particularly quickly | 0:39:24 | 0:39:28 | |

and gives it a good start in life. | 0:39:28 | 0:39:30 | |

Despite the colour of the yolk, | 0:39:35 | 0:39:37 | |

the chicks hatch with fluffy grey feathers. | 0:39:37 | 0:39:40 | |

They're fed on special milk from their parents' crop. | 0:39:41 | 0:39:45 | |

This is not regurgitated food, | 0:39:45 | 0:39:48 | |

but a secretion produced by the lining of the digestive tract. | 0:39:48 | 0:39:53 | |

And it's deep red in colour. | 0:39:53 | 0:39:55 | |

The flamingo chick relies on this for the first few weeks of its life. | 0:40:04 | 0:40:09 | |

And it will eventually enable it to grow its glorious pink plumes. | 0:40:10 | 0:40:13 | |

We now know that much of the flamingo's bizarre | 0:40:18 | 0:40:21 | |

appearance has been shaped by its diet. | 0:40:21 | 0:40:24 | |

But one question continues to baffle scientists - | 0:40:24 | 0:40:27 | |

to which group of birds do the flamingos actually belong? | 0:40:27 | 0:40:30 | |

Some thought that they must be related to ducks and geese | 0:40:31 | 0:40:34 | |

because of their webbed feet and short duck-like beaks. | 0:40:34 | 0:40:38 | |

But others were convinced that with their long legs, | 0:40:38 | 0:40:41 | |

they're more like waders, such as storks. | 0:40:41 | 0:40:44 | |

Recent DNA studies contradict both these suggestions. | 0:40:46 | 0:40:50 | |

They reveal that the flamingo's closest relative may in fact | 0:40:52 | 0:40:56 | |

be a small diving bird that looks nothing like a flamingo. | 0:40:56 | 0:41:00 | |

The grebe. | 0:41:01 | 0:41:03 | |

Further studies found other similarities in the structure | 0:41:06 | 0:41:09 | |

of the eye and the number of feathers on the wing. | 0:41:09 | 0:41:12 | |

So, it seems that flamingos | 0:41:17 | 0:41:18 | |

and grebes are indeed each other's closest relatives. | 0:41:18 | 0:41:22 | |

But over time, diet and lifestyle has shaped the flamingo into a very | 0:41:22 | 0:41:27 | |

different looking bird, far removed from its grebe-like ancestor. | 0:41:27 | 0:41:31 | |

It's fair to say there's nothing else quite like a flamingo. | 0:41:37 | 0:41:41 | |

The flamingo and the blue whale are two very different creatures, | 0:41:46 | 0:41:50 | |

one living on land and one in the deep oceans. | 0:41:50 | 0:41:54 | |

And yet their bodies have been shaped in a similar way, | 0:41:54 | 0:41:57 | |

by their diet, | 0:41:57 | 0:41:59 | |

making each of them a curiosity within its own group. | 0:41:59 | 0:42:02 |