Attenborough and the Giant Egg

Similar Content

Browse content similar to Attenborough and the Giant Egg. Check below for episodes and series from the same categories and more!

Transcript

| Line | From | To | |

|---|---|---|---|

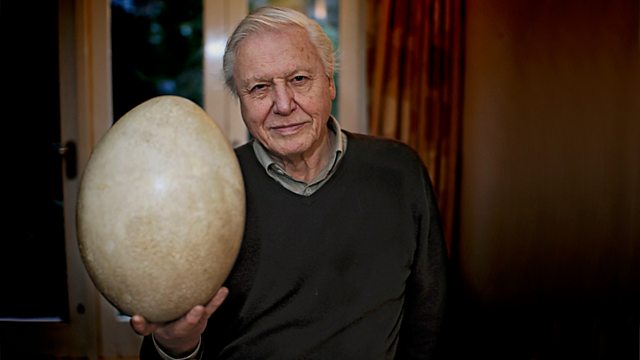

This is a story of an ancient island, an extinct giant | 0:00:06 | 0:00:12 | |

and a mystery that I have been puzzling over for half my life. | 0:00:12 | 0:00:16 | |

50 years ago, I came here to the island of Madagascar | 0:00:18 | 0:00:23 | |

to make a series of programmes about the island's remarkable wildlife. | 0:00:23 | 0:00:26 | |

That was way back in the early days of television | 0:00:28 | 0:00:31 | |

when everything was in black and white. | 0:00:31 | 0:00:33 | |

It was one of the first natural history series that I had made. | 0:00:33 | 0:00:37 | |

Madagascar lies in the Indian ocean, here, | 0:00:37 | 0:00:42 | |

and even on a globe this size, it looks a tiny island, | 0:00:42 | 0:00:45 | |

perhaps because it is dwarfed by this vast continent of Africa. | 0:00:45 | 0:00:49 | |

But in fact it is an immense island. | 0:00:49 | 0:00:51 | |

Over 1,000 miles long, it is bigger than the British Isles. | 0:00:51 | 0:00:55 | |

I was astonished by the animals I saw. | 0:00:56 | 0:01:00 | |

They were unlike anything living elsewhere. | 0:01:00 | 0:01:03 | |

And while I was here, much to my surprise, | 0:01:03 | 0:01:07 | |

I acquired an extraordinary object that has been one of my most treasured possessions ever since. | 0:01:07 | 0:01:12 | |

Down in the south of the island, I found lying in the desert sand | 0:01:14 | 0:01:18 | |

pieces of what looked like very thick eggshell. | 0:01:18 | 0:01:22 | |

I knew that a huge extinct bird had once lived down here. | 0:01:22 | 0:01:26 | |

These must be bits of its eggs. | 0:01:26 | 0:01:29 | |

I asked the local people about them. | 0:01:29 | 0:01:32 | |

They were more than obliging. | 0:01:32 | 0:01:34 | |

The fragments were all small and could give little idea | 0:01:39 | 0:01:43 | |

of the size of a complete egg, but then a young boy brought in these. | 0:01:43 | 0:01:48 | |

At first I thought they were just a collection of exceptionally big bits | 0:01:53 | 0:01:58 | |

that he had picked up over some time, | 0:01:58 | 0:02:01 | |

but then I noticed that two of them looked as if they might fit together. | 0:02:01 | 0:02:05 | |

I had apparently got myself a three dimensional jigsaw puzzle. | 0:02:05 | 0:02:09 | |

And they did fit, | 0:02:12 | 0:02:14 | |

so I joined them with the sticky tape we used to seal our film cams. | 0:02:14 | 0:02:19 | |

Soon I had built up two halves. | 0:02:23 | 0:02:26 | |

This was a single immense egg | 0:02:30 | 0:02:34 | |

and it was virtually complete. | 0:02:37 | 0:02:41 | |

I reckoned it must have contained as much as 140 chicken eggs. | 0:02:41 | 0:02:46 | |

The bird that laid it must have been a giant indeed. | 0:02:46 | 0:02:49 | |

But this raised all kinds of questions. | 0:02:51 | 0:02:53 | |

How old was this egg? When did this bird die out? | 0:02:53 | 0:02:57 | |

And what does it tell us about man's relationship with the wildlife here? | 0:02:57 | 0:03:01 | |

Here is the egg, professionally put together, almost as good as new. | 0:03:09 | 0:03:14 | |

It is to me at any rate a wonderful object. | 0:03:14 | 0:03:18 | |

After all it is the largest egg ever laid by anything. | 0:03:18 | 0:03:23 | |

But what particularly fascinates me | 0:03:23 | 0:03:26 | |

is the thought of the bird that laid it. | 0:03:26 | 0:03:29 | |

What sort of a creature was it? | 0:03:29 | 0:03:31 | |

Well, stories about gigantic birds have been circulating in Europe | 0:03:34 | 0:03:39 | |

since the 13th century when Marco Polo, the great Venetian traveller and explorer, | 0:03:39 | 0:03:46 | |

came back from the East with stories of a huge bird, | 0:03:46 | 0:03:49 | |

"so big that its wings covered an extent of 30 paces | 0:03:49 | 0:03:53 | |

"and its quills were 12 paces long, and it's so strong | 0:03:53 | 0:03:58 | |

"that it will seize an elephant in its talons | 0:03:58 | 0:04:01 | |

"and carry him high into the air and drop him so that he is smashed to pieces." | 0:04:01 | 0:04:05 | |

Stories of a bird so big they could lift an elephant. | 0:04:05 | 0:04:11 | |

And that's what gave it the name of elephant bird. | 0:04:11 | 0:04:14 | |

But after those rather unbelievable stories, | 0:04:16 | 0:04:19 | |

there were other more concrete stories too, in the 17th century. | 0:04:19 | 0:04:25 | |

This is an account of Madagascar written by Flacourt | 0:04:25 | 0:04:28 | |

who was a French governor of the island | 0:04:28 | 0:04:30 | |

and he lists all the animals that he knows in the island of Madagascar and he draws most of them, | 0:04:30 | 0:04:37 | |

but if you look through here, there is no picture of a bird that could be an elephant bird. | 0:04:37 | 0:04:43 | |

There's an egret, there's a heron, but nothing bigger. | 0:04:43 | 0:04:47 | |

But he does say that there was a big ostrich-type bird | 0:04:49 | 0:04:54 | |

in the south of the island. | 0:04:54 | 0:04:56 | |

So maybe he heard stories | 0:04:56 | 0:05:00 | |

of the elephant bird. | 0:05:00 | 0:05:03 | |

But was it alive then? | 0:05:03 | 0:05:05 | |

He doesn't say. Of course, | 0:05:05 | 0:05:08 | |

we know now that the bird is certainly extinct, | 0:05:08 | 0:05:14 | |

but when did it disappear? | 0:05:14 | 0:05:17 | |

Since I collected this egg, techniques have been developed | 0:05:17 | 0:05:21 | |

which enable us to date it, so I've sent off a small fragment of it for that to be done. | 0:05:21 | 0:05:27 | |

It will take a little time for the results to come through | 0:05:27 | 0:05:32 | |

but after 50 years, I guess I can wait a few weeks longer. | 0:05:32 | 0:05:36 | |

Meanwhile, I'm off to Madagascar to have another look at its wonderful animals | 0:05:40 | 0:05:46 | |

and see how things have changed in the last 50 years. | 0:05:46 | 0:05:50 | |

Some species are thought to have disappeared since I was last here | 0:05:50 | 0:05:54 | |

and new ones have also been discovered. | 0:05:54 | 0:05:56 | |

Could the story of the elephant bird, whatever it turns out to be, | 0:05:57 | 0:06:01 | |

help me to understand what is going on there today? | 0:06:01 | 0:06:04 | |

50 years ago, Madagascar was little known, certainly in Britain. | 0:06:10 | 0:06:15 | |

Until only a few years before, it had been a French colony. | 0:06:15 | 0:06:19 | |

I really didn't know anything about it when I started to read about it | 0:06:19 | 0:06:25 | |

and the only illustrations I could find were drawings or photographs | 0:06:25 | 0:06:29 | |

of stuffed specimens in French publications. | 0:06:29 | 0:06:31 | |

So I thought, OK, that's great, nobody else has filmed there, | 0:06:31 | 0:06:36 | |

and I don't really think there had really been | 0:06:36 | 0:06:39 | |

any natural history film made from Madagascar at all in 1960 that I could find. | 0:06:39 | 0:06:44 | |

It was just me and Geoff Mulligan with his camera, and we were there for four months. | 0:06:46 | 0:06:51 | |

Because the island has been cut off for so long, | 0:06:51 | 0:06:55 | |

evolution has had a chance to produce a whole range of unique animals and plants. | 0:06:55 | 0:07:01 | |

But first, what about the elephant bird? | 0:07:05 | 0:07:09 | |

Beyond the legends, what more do we know about it? | 0:07:09 | 0:07:12 | |

The country's capital is Antananarivo, or Tana, as the locals call it, | 0:07:18 | 0:07:23 | |

and the place to go if you want to find out about the island's natural history is obviously its museum. | 0:07:23 | 0:07:29 | |

It had stuffed examples of some of the animals I already knew something about. | 0:07:31 | 0:07:36 | |

But I also found a mounted skeleton of the huge bird that interests me so much, | 0:07:41 | 0:07:48 | |

one of the very few that exists. | 0:07:48 | 0:07:51 | |

So how tall was the elephant bird? | 0:07:53 | 0:07:57 | |

Not an easy question to answer because very few skeletons are totally complete | 0:07:57 | 0:08:03 | |

and so many of the mounted specimens have been put together | 0:08:03 | 0:08:07 | |

with a number bones from different specimens, | 0:08:07 | 0:08:10 | |

and if you get overenthusiastic maybe it's quite possible | 0:08:10 | 0:08:14 | |

that you stick in one or two extra neck bones. | 0:08:14 | 0:08:17 | |

So we can't be sure about the length of the neck, | 0:08:17 | 0:08:20 | |

nor can we be sure about the posture, really. | 0:08:20 | 0:08:24 | |

This one looks to me rather front heavy | 0:08:24 | 0:08:27 | |

and it could well be that in life the animal was more upright, | 0:08:27 | 0:08:32 | |

in which case it stood very tall indeed. | 0:08:32 | 0:08:35 | |

What - ten feet, 12 feet, that sort of size - | 0:08:35 | 0:08:39 | |

in order to be able to reach the leaves of trees on which it browsed. | 0:08:39 | 0:08:43 | |

But a more safe characteristic is weight, | 0:08:43 | 0:08:48 | |

and you can be fairly sure the estimate of that, | 0:08:48 | 0:08:53 | |

and it's reckoned that the elephant bird weighed around half a tonne. | 0:08:53 | 0:08:57 | |

The extinct moas of New Zealand might perhaps have been taller, | 0:09:03 | 0:09:07 | |

but this was certainly the heaviest bird that ever existed | 0:09:07 | 0:09:10 | |

and, of course, it was flightless, like an ostrich. | 0:09:10 | 0:09:13 | |

Most of its remains have been found down in the dry, hot, southern end of the island | 0:09:14 | 0:09:19 | |

where I had collected my egg fragments, | 0:09:19 | 0:09:22 | |

so, on leaving Tana, that's where we headed. | 0:09:22 | 0:09:26 | |

Sounds like forever, 50 years, to me, | 0:09:26 | 0:09:29 | |

but it's really the day before yesterday, I reckon, | 0:09:29 | 0:09:32 | |

that I was here doing that sort of stuff. | 0:09:32 | 0:09:35 | |

I can't believe that it's 50 years. | 0:09:35 | 0:09:38 | |

Southern Madagascar really is one of the oddest places on the world, | 0:09:46 | 0:09:49 | |

if only because of its bizarre vegetation. | 0:09:49 | 0:09:52 | |

I hadn't known what the spiny forest was. | 0:09:57 | 0:10:00 | |

They showed me plants like long fingers 20 feet high, | 0:10:00 | 0:10:06 | |

30 feet high, with spines all over them and little leaves, you know. | 0:10:06 | 0:10:10 | |

Extraordinary. | 0:10:10 | 0:10:12 | |

This spiny forest was once widespread in the south, | 0:10:12 | 0:10:16 | |

but now there are only a few pockets of it left. | 0:10:16 | 0:10:19 | |

Big leaves would lose a lot of precious water in a hot desert, | 0:10:25 | 0:10:28 | |

so these plants have very small ones that are protected from browsing animals by sharp spines. | 0:10:28 | 0:10:34 | |

But what browsers? | 0:10:35 | 0:10:37 | |

Presumably, one was the elephant bird. | 0:10:37 | 0:10:41 | |

Some browsers, however, are still around, | 0:10:44 | 0:10:47 | |

and 50 years ago, we went to look for them. | 0:10:47 | 0:10:50 | |

The spines make this a fairly uncomfortable place to move around in. | 0:10:54 | 0:10:58 | |

But eventually we found those browsers. | 0:11:04 | 0:11:07 | |

And they are still here. | 0:11:08 | 0:11:10 | |

Sifakas, a wonderful type of lemur. | 0:11:12 | 0:11:16 | |

They are feeding on bark, stripping away the bark. | 0:11:16 | 0:11:19 | |

They are not particularly upset by my presence any more than they were when I first saw them 50 years ago. | 0:11:23 | 0:11:30 | |

What is astonishing about them is the way they move through the forest. | 0:11:32 | 0:11:37 | |

Very unlike monkeys. | 0:11:37 | 0:11:40 | |

Monkeys, when they leap, leap hands first, | 0:11:40 | 0:11:43 | |

their torso more or less level, | 0:11:43 | 0:11:46 | |

but these marvellous creatures | 0:11:46 | 0:11:49 | |

jump upright because they land with their feet first, which accounts for | 0:11:49 | 0:11:53 | |

why when they come down to the ground very rarely | 0:11:53 | 0:11:57 | |

their legs are so long they can't walk on all fours, | 0:11:57 | 0:12:01 | |

as many monkeys do, but have to stand upright on their very long legs and their rather short arms, | 0:12:01 | 0:12:09 | |

and that gives them this lovely balletic movement | 0:12:09 | 0:12:13 | |

when they get around on the ground. | 0:12:13 | 0:12:15 | |

There are quite a number of different species of these | 0:12:19 | 0:12:23 | |

and they differ mostly in their colouration. | 0:12:23 | 0:12:26 | |

This one with its dark brown...cap. | 0:12:26 | 0:12:31 | |

And I think this is actually one of the loveliest. | 0:12:32 | 0:12:35 | |

I can just hear them making that slight...siffa, siffa noise, | 0:12:38 | 0:12:42 | |

which is a kind of, I think, uneasy noise that they make | 0:12:42 | 0:12:47 | |

when they are just a little worried and which gives them their name of sifaka. | 0:12:47 | 0:12:52 | |

Their faces with that long snout and moist nose, | 0:12:57 | 0:13:03 | |

really rather dog-like, | 0:13:03 | 0:13:06 | |

but it's when you see their hands | 0:13:06 | 0:13:09 | |

that you realise that they are related to monkeys and to us. | 0:13:09 | 0:13:13 | |

These grasping hands. | 0:13:13 | 0:13:15 | |

I've actually had a pet lemur a long, long time ago | 0:13:18 | 0:13:22 | |

and it held onto my hand in the most charming way. | 0:13:22 | 0:13:26 | |

On that first trip, I kept a journal and reading it now reminds me | 0:13:28 | 0:13:33 | |

of how excited I was, seeing these creatures for the first time. | 0:13:33 | 0:13:37 | |

"Before they started feeding, the adult male and female treated us to a captivating display of wrestling. | 0:13:39 | 0:13:46 | |

"The female was sitting on her bottom on the branch, her feet dangling, | 0:13:46 | 0:13:49 | |

"while the male came along and put a half nelson on her. | 0:13:49 | 0:13:52 | |

"Then the match started. | 0:13:52 | 0:13:54 | |

"There was no question of sex nor of aggression, for they often broke off to look at us. | 0:13:54 | 0:13:58 | |

"It was pure play and enchanting to watch." | 0:13:58 | 0:14:01 | |

I've got notes here of what we filmed. | 0:14:08 | 0:14:12 | |

It's all 100-foot reels. | 0:14:12 | 0:14:14 | |

A 100-foot reel runs for two minutes 40, you know, two minutes 40, | 0:14:14 | 0:14:19 | |

and you've got to stop and take the thing out as well, | 0:14:19 | 0:14:21 | |

and of course the lenses we had were very poor | 0:14:21 | 0:14:24 | |

and we didn't have zooms either, | 0:14:24 | 0:14:27 | |

so now, if you see something up there, you've got the wide shot | 0:14:27 | 0:14:30 | |

and then you zoom in quickly and you've got it. | 0:14:30 | 0:14:33 | |

But if you did that then you'd have to take that lens out and put on another socking great lens. | 0:14:33 | 0:14:40 | |

I had never seen a living sifaka until I came here to Madagascar. | 0:14:46 | 0:14:51 | |

It was such a shock and a thrill | 0:14:51 | 0:14:55 | |

to see them in the wild for the first time. | 0:14:55 | 0:14:59 | |

And it's just about as great a thrill right now. | 0:14:59 | 0:15:04 | |

They're bounding away on the ground. | 0:15:04 | 0:15:06 | |

Sifakas are well adapted to living in this world of spines and thorns, | 0:15:19 | 0:15:24 | |

and so, doubtless, was the elephant bird, | 0:15:24 | 0:15:27 | |

but adaptation is often a two-way process. | 0:15:27 | 0:15:30 | |

This is the seed of a particularly strange plant | 0:15:30 | 0:15:35 | |

that grows in this arid, spiny forest. | 0:15:35 | 0:15:38 | |

It is armed with a series of ferocious hooks | 0:15:38 | 0:15:42 | |

which would have caught on the legs of the elephant bird | 0:15:42 | 0:15:46 | |

and so be distributed throughout the forest. | 0:15:46 | 0:15:49 | |

Now, presumably, it's us and our cattle who do the job. | 0:15:50 | 0:15:55 | |

As you go further south, it gets drier and hotter until eventually | 0:15:56 | 0:16:01 | |

there's not enough moisture to sustain even the spiny forest. | 0:16:01 | 0:16:05 | |

And here, once again, I found egg fragments. | 0:16:05 | 0:16:07 | |

Lots of them. | 0:16:07 | 0:16:09 | |

50 years ago, I thought I had been amazingly sharp eyed to find a few bits | 0:16:09 | 0:16:14 | |

and I certainly was very lucky to be brought enough to reconstruct an egg. | 0:16:14 | 0:16:20 | |

But there were so many pieces here, | 0:16:20 | 0:16:22 | |

I think that I must have been half blind before, | 0:16:22 | 0:16:25 | |

or in quite the wrong place. | 0:16:25 | 0:16:26 | |

Of course, these thick shells don't turn to powder, | 0:16:28 | 0:16:33 | |

like say, chicken egg shells would do over a few days, | 0:16:33 | 0:16:37 | |

but remain solid and firm for a long time. | 0:16:37 | 0:16:40 | |

Even so there are vast quantities of shells out there | 0:16:40 | 0:16:44 | |

so there must have been a very substantial population of birds. | 0:16:44 | 0:16:49 | |

What happened to them? | 0:16:49 | 0:16:51 | |

Now, it's so arid that it's difficult to imagine | 0:16:53 | 0:16:56 | |

huge flocks of giant flightless birds living here, | 0:16:56 | 0:17:01 | |

but they must have done so. | 0:17:01 | 0:17:02 | |

How greatly has the climate of Madagascar changed? | 0:17:04 | 0:17:07 | |

We can get clues from examining the fossilised bones of other animals | 0:17:07 | 0:17:11 | |

that were around at the same time as the elephant bird, | 0:17:11 | 0:17:15 | |

and there were certainly some very extraordinary ones, | 0:17:15 | 0:17:18 | |

some quite tiny and some giants, quite unlike anything around now. | 0:17:18 | 0:17:22 | |

This is the skull of the biggest of all the lemurs. | 0:17:27 | 0:17:32 | |

It's got a head much bigger than mine | 0:17:32 | 0:17:34 | |

and indeed it was probably about the size of a young gorilla. | 0:17:34 | 0:17:39 | |

This animal lived in trees | 0:17:39 | 0:17:42 | |

and that's confirmed by a look at its teeth. | 0:17:42 | 0:17:47 | |

These were the teeth of a leaf-eating animal. | 0:17:47 | 0:17:51 | |

Not a grazer, not a meat eater, but a leaf eater. | 0:17:51 | 0:17:57 | |

So this animal lived in trees and probably hung around | 0:17:57 | 0:18:02 | |

rather like a koala, only very, very much bigger, | 0:18:02 | 0:18:07 | |

and that tells us that where this lived there was forest. | 0:18:07 | 0:18:11 | |

The rolling hills of the island are now nearly all bare of trees, | 0:18:14 | 0:18:19 | |

yet bones of this giant lemur have been found in many widely separated places all over the island. | 0:18:19 | 0:18:25 | |

Strong evidence that once the whole of Madagascar was forested. | 0:18:25 | 0:18:29 | |

When I was here 50 years ago, | 0:18:29 | 0:18:31 | |

I speculated that elephant birds had disappeared because their habitat had dried out | 0:18:31 | 0:18:37 | |

and I put that down to a change in climate. | 0:18:37 | 0:18:40 | |

Now we know that, although the climate here has indeed become much drier, | 0:18:40 | 0:18:45 | |

that change took place many thousands of years ago | 0:18:45 | 0:18:48 | |

and elephant birds living in the spiny forest managed to survive it, | 0:18:48 | 0:18:53 | |

so climate change alone can't be blamed for the bird's extinction. | 0:18:53 | 0:18:58 | |

Are there any other clues that might suggest an alternative explanation for that | 0:19:03 | 0:19:09 | |

and for the fact that the giant lemur's forests have also gone? | 0:19:09 | 0:19:14 | |

Well, it's been discovered that those giant lemurs all disappeared over a very short space of time. | 0:19:16 | 0:19:22 | |

And that was when human beings arrived. | 0:19:24 | 0:19:26 | |

Madagascar was one of the last places on earth to be reached by human beings. | 0:19:54 | 0:19:59 | |

They didn't get here until around 2,000 years ago | 0:19:59 | 0:20:02 | |

and then, of course, there were just a few hundred. | 0:20:02 | 0:20:05 | |

50 years ago, there were around six million. | 0:20:05 | 0:20:08 | |

Today, there are 20 million. | 0:20:08 | 0:20:11 | |

Was it human beings who exterminated much of the island's animals, | 0:20:14 | 0:20:20 | |

the elephant bird, as well as the giant lemurs? | 0:20:20 | 0:20:22 | |

Did they perhaps hunt them for food? | 0:20:22 | 0:20:26 | |

One of the ways that you can tell whether or not human beings | 0:20:26 | 0:20:30 | |

hunted an animal is to look at the animal's bones. | 0:20:30 | 0:20:34 | |

This is the bone of an extinct lemur | 0:20:34 | 0:20:39 | |

that dates from about 2,000 years ago | 0:20:39 | 0:20:43 | |

when human beings first came to this island, | 0:20:43 | 0:20:46 | |

and when you look at it, you can see at the top there, | 0:20:46 | 0:20:50 | |

cut marks. | 0:20:50 | 0:20:52 | |

So we know that this lemur was killed, | 0:20:52 | 0:20:55 | |

or at least eaten, by human beings | 0:20:55 | 0:20:59 | |

who cut the flesh away from the bone with some kind of knife. | 0:20:59 | 0:21:04 | |

But the interesting thing is, | 0:21:04 | 0:21:07 | |

although we also find elephant bird bones, | 0:21:07 | 0:21:10 | |

hardly a one of the elephant bird bones have cut marks, | 0:21:10 | 0:21:15 | |

so we can't really blame the disappearance of the elephant bird on hunters. | 0:21:15 | 0:21:22 | |

If it wasn't climate change or hunting, what else could it have been? | 0:21:24 | 0:21:29 | |

Although Madagascar is only separated from Africa by a relatively narrow stretch of sea, | 0:21:29 | 0:21:35 | |

many of the first settlers came not from there | 0:21:35 | 0:21:38 | |

but from Southeast Asia, thousands of miles away. | 0:21:38 | 0:21:41 | |

In fact, the people who live in the centre part of Madagascar | 0:21:41 | 0:21:45 | |

originally came from right across the other side of the Indian Ocean, | 0:21:45 | 0:21:50 | |

here in the Malayan region. | 0:21:50 | 0:21:52 | |

They must certainly have hunted the animals, | 0:21:54 | 0:21:56 | |

but they also did something else which in the long run | 0:21:56 | 0:21:59 | |

was far more devastating for the island's wildlife. | 0:21:59 | 0:22:02 | |

They were farmers, and they cleared the forest to grow rice | 0:22:02 | 0:22:06 | |

and provide grazing for their cattle. | 0:22:06 | 0:22:09 | |

As the numbers of people increased | 0:22:09 | 0:22:11 | |

so more and more forest was cut and burned. | 0:22:11 | 0:22:14 | |

It is a process that is still going on. | 0:22:14 | 0:22:17 | |

So, all over the island, the landscape began to change. | 0:22:29 | 0:22:34 | |

I am on my way to the west of the island | 0:22:47 | 0:22:50 | |

where a few small patches of that ancient forest still remain. | 0:22:50 | 0:22:54 | |

These strange, beautiful trees, | 0:22:54 | 0:22:56 | |

baobabs, are fire resistant and too big to cut down | 0:22:56 | 0:23:01 | |

so in many places they are the only remnants left | 0:23:01 | 0:23:04 | |

of the original forest that once covered this land. | 0:23:04 | 0:23:08 | |

It would have been difficult for a creature the size of an elephant bird | 0:23:08 | 0:23:12 | |

to live without vegetation of some kind, | 0:23:12 | 0:23:14 | |

and today even the smallest of animals are struggling to survive here. | 0:23:14 | 0:23:18 | |

One of those that have managed to do so is the tiniest of all known lemurs. | 0:23:21 | 0:23:27 | |

It's called Madame Berthe's mouse lemur, and it was only discovered ten years ago. | 0:23:27 | 0:23:33 | |

Melanie Dammhahn is part of a team of scientists | 0:23:34 | 0:23:37 | |

who are studying the animal, trying to work out how to protect it. | 0:23:37 | 0:23:41 | |

Ohh! | 0:23:43 | 0:23:46 | |

-Tiny, tiny. -Tiny, tiny. | 0:23:46 | 0:23:49 | |

Just only 30 gram body weight. | 0:23:49 | 0:23:51 | |

-Yeah. Smallest primate in the world. -Smallest primate in the world. | 0:23:51 | 0:23:54 | |

-Big eyes, small ears. -Very big eyes. | 0:23:54 | 0:23:57 | |

-Yeah. -And a wet nose. | 0:23:57 | 0:23:59 | |

-Yeah. -Yeah. | 0:23:59 | 0:24:00 | |

'Melanie and her colleagues catch these lemurs and tag them to build up a picture of their behaviour, | 0:24:00 | 0:24:06 | |

'essential knowledge if they are to be properly protected.' | 0:24:06 | 0:24:10 | |

And how long will he have been in there now? | 0:24:10 | 0:24:12 | |

-A few hours. -Is that all? -So we collect him at night... | 0:24:12 | 0:24:15 | |

-Yeah. -..and he stays in camp and sleeps in there, then we release him the next day. | 0:24:15 | 0:24:19 | |

-And you have caught him how many times? -Maybe around 20. | 0:24:19 | 0:24:21 | |

-So he's accustomed to it. -He's accustomed to it. | 0:24:21 | 0:24:25 | |

-And do they travel very far? -They travel very far. -Really? | 0:24:25 | 0:24:28 | |

-They have three-hectare home range so that is quite a bit for an animal like that. -Certainly is. -Yes. | 0:24:28 | 0:24:34 | |

-They might even run five kilometres a night. -Really? | 0:24:34 | 0:24:37 | |

-Yeah. An animal like that. -Amazing. -I think that is amazing, yeah. | 0:24:37 | 0:24:41 | |

OK, let's see him go. | 0:24:41 | 0:24:43 | |

He's coming. | 0:24:48 | 0:24:49 | |

Come on. | 0:24:51 | 0:24:52 | |

Come on, little one. | 0:24:52 | 0:24:55 | |

That's it. That's it. | 0:24:56 | 0:24:57 | |

Oh! | 0:24:57 | 0:24:58 | |

The work Melanie and her team are doing is vital for the survival of this little lemur. | 0:25:02 | 0:25:08 | |

It's also revealing just why it is that this tiny creature lives here and nowhere else. | 0:25:08 | 0:25:13 | |

This particular liana belongs to a species that only grows in this part of the forest | 0:25:16 | 0:25:24 | |

and on it, and on no other kind of liana, lives this little insect. | 0:25:24 | 0:25:29 | |

It's a bug which feeds by sticking its mouth parts | 0:25:29 | 0:25:33 | |

into the liana and sucking out the sap. | 0:25:33 | 0:25:36 | |

It then digest what it wants and excretes the rest as honeydew, a sort of sugary liquid. | 0:25:37 | 0:25:44 | |

And it's that honeydew, that sugar, | 0:25:44 | 0:25:48 | |

that Madame Berthe's lemur needs in its diet. | 0:25:48 | 0:25:53 | |

So Madame Berthe's lemur is only found | 0:25:53 | 0:25:57 | |

in this particular part of the forest | 0:25:57 | 0:26:00 | |

because of this insect and this liana, | 0:26:00 | 0:26:03 | |

which just shows how complicated ecological connections can be | 0:26:03 | 0:26:08 | |

and how much you have to know about an animal | 0:26:08 | 0:26:11 | |

if you are really going to conserve it. | 0:26:11 | 0:26:14 | |

It's more than likely that the elephant bird was nowhere near as fussy as a mouse lemur, | 0:26:19 | 0:26:24 | |

but it certainly needed much greater quantities of food. | 0:26:24 | 0:26:28 | |

So, as more and more of the forest was cleared, | 0:26:32 | 0:26:36 | |

there was less and less room for animals of all kinds. | 0:26:36 | 0:26:40 | |

Elephant birds were among the first victims of deforestation. | 0:26:47 | 0:26:51 | |

As people came in and cleared the bush, in order to make space for their own crops, | 0:26:51 | 0:26:57 | |

there was less and less foliage for birds to browse on | 0:26:57 | 0:27:00 | |

and no leaves whatever on the great trunks of the baobabs. | 0:27:00 | 0:27:04 | |

And if we know that, unlike the giant lemurs, | 0:27:06 | 0:27:09 | |

the elephant bird didn't disappear as soon as the people arrived. | 0:27:09 | 0:27:12 | |

Recent archaeological research suggests that the birds lived | 0:27:12 | 0:27:17 | |

alongside human beings for hundreds of years. | 0:27:17 | 0:27:19 | |

Perhaps they were protected by something | 0:27:21 | 0:27:24 | |

that is still deeply rooted in the lives of the Malagasy people - | 0:27:24 | 0:27:27 | |

fady - a belief about the intimate way in which human beings are connected with the natural world. | 0:27:27 | 0:27:33 | |

They believe, for example, that many species of animal contain | 0:27:34 | 0:27:38 | |

the spirits of their ancestors and must not therefore be killed. | 0:27:38 | 0:27:41 | |

When I was here making the Zoo Quest programmes, we watched a traditional ceremony | 0:27:43 | 0:27:48 | |

which centred around a fady connected with Madagascar's only surviving giant, the crocodile. | 0:27:48 | 0:27:55 | |

Here, at the sacred lake of Anivorano, | 0:27:55 | 0:27:58 | |

they tell the story of a wandering holy man who appeared in the village. | 0:27:58 | 0:28:03 | |

No-one apart from one old woman offered him refreshment. | 0:28:03 | 0:28:08 | |

After warning the old woman to leave, | 0:28:08 | 0:28:10 | |

he then flooded the whole village, drowning everyone in it except her. | 0:28:10 | 0:28:14 | |

The people here believe that the crocodiles in this lake | 0:28:14 | 0:28:18 | |

are descendents of those original villagers | 0:28:18 | 0:28:21 | |

and they come here to give them sacrifices of meat | 0:28:21 | 0:28:24 | |

in return for their blessings. | 0:28:24 | 0:28:26 | |

Many animals in Madagascar have some kind of fady attached to them. | 0:28:32 | 0:28:37 | |

This is a chameleon | 0:28:41 | 0:28:43 | |

and Madagascar is the home of the chameleons. | 0:28:43 | 0:28:48 | |

There are more different kinds of chameleons | 0:28:48 | 0:28:51 | |

and more spectacular chameleons here | 0:28:51 | 0:28:53 | |

than anywhere else in the world. | 0:28:53 | 0:28:55 | |

They are, of course, very specialised lizards, | 0:28:55 | 0:28:59 | |

but local people are very frightened of them. | 0:28:59 | 0:29:02 | |

They move in this odd way and they have these bizarre eyes | 0:29:02 | 0:29:06 | |

and they think that one glance from a chameleon is risking death | 0:29:06 | 0:29:11 | |

and to hold one would be disaster. | 0:29:11 | 0:29:13 | |

And when we were last here, | 0:29:13 | 0:29:16 | |

somebody broke into our car with all our equipment in it | 0:29:16 | 0:29:21 | |

and broke the window and so we couldn't lock the car. | 0:29:21 | 0:29:25 | |

So I took one of these splendid chameleons and put it on the steering wheel | 0:29:25 | 0:29:30 | |

and when anybody opened the car door it sort of glowered at them | 0:29:30 | 0:29:36 | |

and nobody did...except us. | 0:29:36 | 0:29:39 | |

These beliefs in fady are still very powerful | 0:29:52 | 0:29:55 | |

and widespread in Madagascar | 0:29:55 | 0:29:58 | |

and in some cases it's they that have been responsible | 0:29:58 | 0:30:02 | |

for the very survival of a species. | 0:30:02 | 0:30:04 | |

This giant baobab is one of the most famous individual trees | 0:30:08 | 0:30:12 | |

in the whole of Madagascar. | 0:30:12 | 0:30:14 | |

The people believe that it's the home to the spirits of the dead | 0:30:16 | 0:30:20 | |

and they bring offerings which they place around its base, | 0:30:20 | 0:30:23 | |

of rum and other things, to ask the ancestors to bring them luck. | 0:30:23 | 0:30:28 | |

But the spirits will only remain | 0:30:28 | 0:30:30 | |

as long as the forest surrounds the tree, | 0:30:30 | 0:30:34 | |

so, thanks to this tree and that belief, | 0:30:34 | 0:30:37 | |

one of the best pieces of dry forest in the whole of Madagascar is still protected. | 0:30:37 | 0:30:43 | |

Many Malagasy communities have such beliefs about the natural world. | 0:30:46 | 0:30:51 | |

Could it be that it was fady that helped to protect the last dwindling populations of elephant birds, | 0:30:51 | 0:30:57 | |

enabling them to survive longer than they might otherwise have done? | 0:30:57 | 0:31:01 | |

It's easy to imagine that creatures whose eggs were big enough to start legends all over Europe | 0:31:03 | 0:31:09 | |

would be surrounded by feelings of awe or even fear. | 0:31:09 | 0:31:13 | |

But that did not save the elephant bird in the long run. | 0:31:14 | 0:31:18 | |

The territories they required were just too big. | 0:31:18 | 0:31:22 | |

Madagascar has one of the highest rates of forest loss of anywhere in the world. | 0:31:25 | 0:31:31 | |

It's estimated that 80% of it has now gone. | 0:31:31 | 0:31:34 | |

All the wetter parts of the island were once covered by rainforest, | 0:31:38 | 0:31:42 | |

which, like rainforest everywhere, | 0:31:42 | 0:31:44 | |

was hugely rich in animals and plant species. | 0:31:44 | 0:31:47 | |

And this being Madagascar, most were species that existed nowhere else. | 0:31:47 | 0:31:52 | |

The changes here have been particularly dramatic. | 0:31:52 | 0:31:57 | |

When I was here in 1960, | 0:31:57 | 0:32:00 | |

all this land was covered in rainforest, | 0:32:00 | 0:32:04 | |

trees 100 feet high, with lemurs and all kinds of birds and insects. | 0:32:04 | 0:32:09 | |

And then they built this sawmill | 0:32:11 | 0:32:14 | |

and for 25 years it operated, | 0:32:14 | 0:32:17 | |

consuming the forest until the forest was all gone. | 0:32:17 | 0:32:21 | |

So then they left the sawmill and the land has gone to waste. | 0:32:21 | 0:32:26 | |

They also started to mine here for nickel. | 0:32:29 | 0:32:34 | |

Madagascar, in fact, has some of the richest untapped mineral deposits in the world. | 0:32:35 | 0:32:41 | |

Exploiting them requires great corridors to be cut through the forest. | 0:32:41 | 0:32:45 | |

Many animals that require big territories won't cross such corridors, | 0:32:45 | 0:32:50 | |

so, just like the elephant bird, | 0:32:50 | 0:32:52 | |

they are squeezed into smaller and smaller patches | 0:32:52 | 0:32:56 | |

and ultimately they vanish, just as the elephant bird did. | 0:32:56 | 0:33:00 | |

This patch of forest in Andasibe on the eastern side of the island | 0:33:04 | 0:33:09 | |

is one of the largest remaining fragments and it's the last home of the biggest of all surviving lemurs, | 0:33:09 | 0:33:17 | |

the indri. | 0:33:17 | 0:33:18 | |

Joseph has lived here all his life. | 0:33:22 | 0:33:26 | |

In fact, he was here when I was filming in 1960, although we didn't meet. | 0:33:27 | 0:33:32 | |

Then, he was hunting the indri for food. | 0:33:32 | 0:33:36 | |

At that time, I had an idea that stories about the indri | 0:33:44 | 0:33:49 | |

might have given rise to myths almost as fantastic | 0:33:49 | 0:33:52 | |

as those surrounding the elephant bird. | 0:33:52 | 0:33:55 | |

Many people consider that this strange creature is the origin | 0:33:57 | 0:34:02 | |

of the legend of a dog-headed man. | 0:34:02 | 0:34:05 | |

Marco Polo wrote about the dog-headed man | 0:34:05 | 0:34:08 | |

and this is an illustration from a natural history book published some 300 years ago. | 0:34:08 | 0:34:14 | |

Obviously we wanted to film this | 0:34:14 | 0:34:16 | |

and before we went to Madagascar | 0:34:16 | 0:34:18 | |

I visited a very distinguished British naturalist | 0:34:18 | 0:34:21 | |

who had spent seven years there and asked him about the indris. | 0:34:21 | 0:34:25 | |

He told me that as far as he knew it had never been photographed or filmed alive. | 0:34:25 | 0:34:29 | |

The animal which was the most dramatic in the series by a long way | 0:34:29 | 0:34:34 | |

was the indri, which we had been the first people to photograph alive. | 0:34:34 | 0:34:39 | |

It took us a hell of time to find it, we were traipsing through the forest | 0:34:41 | 0:34:45 | |

and nearly always, you heard a call so you'd go through the bush | 0:34:45 | 0:34:51 | |

and look for it and then, as soon as it saw you, whoof, it was gone, | 0:34:51 | 0:34:54 | |

bounding through the forest. So all we got for days and days | 0:34:54 | 0:34:58 | |

was nothing but backsides of these things sailing away from you. | 0:34:58 | 0:35:01 | |

Since people at that time, like Joseph, were still hunting indris, | 0:35:03 | 0:35:08 | |

it was hardly surprising that they were scared of us. | 0:35:08 | 0:35:11 | |

After several days of failure, I had an idea. | 0:35:11 | 0:35:15 | |

I decided to record their extraordinary calls and then replay the sound in the hope | 0:35:15 | 0:35:20 | |

that the animals might call in response and reveal themselves, or even come closer. | 0:35:20 | 0:35:26 | |

SCREECHING | 0:35:26 | 0:35:29 | |

SCREECHING CONTINUES | 0:35:40 | 0:35:42 | |

And it worked. | 0:35:42 | 0:35:44 | |

Although we didn't get as close as I might have wished, | 0:35:47 | 0:35:50 | |

we watched them for several days. | 0:35:50 | 0:35:52 | |

SCREECHING | 0:35:52 | 0:35:55 | |

"We never saw a group of more than four. | 0:36:08 | 0:36:12 | |

"This I think is the source of much of the charm of it. | 0:36:12 | 0:36:14 | |

"Monkeys living in troops have a troop discipline, | 0:36:14 | 0:36:17 | |

'an order of seniority is savagely maintained by battle, | 0:36:17 | 0:36:20 | |

"the males fighting one another ferociously. | 0:36:20 | 0:36:23 | |

"Not so with indri. | 0:36:23 | 0:36:25 | |

"They live en famille. The old male doesn't need to assert his rank | 0:36:25 | 0:36:29 | |

"by fighting, and consequently the atmosphere is one of affection. | 0:36:29 | 0:36:32 | |

"Once we saw a young male join a young female, | 0:36:32 | 0:36:35 | |

"sitting behind her, his legs stretched out on either side of her. | 0:36:35 | 0:36:39 | |

"They licked and embraced one another for half an hour, | 0:36:39 | 0:36:43 | |

-"then suddenly a bird screeched..." -BIRD SCREECHES | 0:36:43 | 0:36:47 | |

"..loudly and startlingly. | 0:36:47 | 0:36:48 | |

"Immediately, the male put a protective and reassuring arm around her. | 0:36:48 | 0:36:52 | |

"It was most touching to see." | 0:36:52 | 0:36:54 | |

-SCOFFS -Anthropomorphism run riot, but there you are, that's what I wrote here. | 0:36:54 | 0:36:58 | |

Joseph, the one-time hunter, still uses his skills to track the indri, | 0:37:04 | 0:37:09 | |

but no longer in order to kill them. | 0:37:09 | 0:37:11 | |

Now he works as a forest guide. | 0:37:11 | 0:37:14 | |

What made you stop hunting them? | 0:37:18 | 0:37:21 | |

Have people's attitudes towards the indri changed over the years? | 0:37:50 | 0:37:54 | |

Without Joseph to help us, it would have been impossible for us to get near the indri, | 0:38:23 | 0:38:28 | |

but this group is so used to him that they are not frightened. | 0:38:28 | 0:38:32 | |

Indeed, it seemed to me that they almost welcomed his company. | 0:38:32 | 0:38:36 | |

Thanks to him, I now had a chance, for the very first time, | 0:38:41 | 0:38:45 | |

to get really close to them. | 0:38:45 | 0:38:47 | |

Oh. | 0:38:55 | 0:38:57 | |

They could easily collect these leaves from the trees themselves | 0:40:29 | 0:40:34 | |

but they seem to choose to take them from the hand of a human being. | 0:40:34 | 0:40:38 | |

Well, that was an astonishing experience. | 0:40:42 | 0:40:47 | |

50 years ago | 0:40:49 | 0:40:51 | |

I spent days and days and days searching the forests for these, | 0:40:51 | 0:40:57 | |

following the noise, | 0:40:57 | 0:40:59 | |

but now this group is so accustomed to seeing people around | 0:40:59 | 0:41:05 | |

that I have been right close up to them, | 0:41:05 | 0:41:10 | |

something I had never believed could have been possible. | 0:41:10 | 0:41:13 | |

I thought these were the most elusive, shy creatures, | 0:41:16 | 0:41:22 | |

it certainly took me a long time to find them, | 0:41:22 | 0:41:26 | |

but that they can now be so trusting | 0:41:26 | 0:41:29 | |

is a marvellous testament | 0:41:29 | 0:41:31 | |

to how people here now react towards them and cherish them. | 0:41:31 | 0:41:36 | |

A heart-warming kind of realisation | 0:41:41 | 0:41:44 | |

that wild creatures like this and human beings | 0:41:44 | 0:41:48 | |

can live alongside one another in harmony. | 0:41:48 | 0:41:52 | |

And they are such astonishing creatures. | 0:41:52 | 0:41:56 | |

I mean, apart from being so beautiful, | 0:41:56 | 0:41:58 | |

they have these very staring eyes | 0:41:58 | 0:42:00 | |

looking straight at you, straight through you, | 0:42:00 | 0:42:04 | |

and then they have these very human-like hands, | 0:42:04 | 0:42:08 | |

just taking them. | 0:42:08 | 0:42:09 | |

When you look down at their feet, | 0:42:11 | 0:42:14 | |

huge great calliper feet, | 0:42:14 | 0:42:16 | |

when they decided that they've had enough of you, | 0:42:16 | 0:42:19 | |

they simply flex those enormous hind legs | 0:42:19 | 0:42:22 | |

and just with vast bound of, what, I suppose... | 0:42:22 | 0:42:26 | |

three yards, four yards, just whoo and they've gone. | 0:42:26 | 0:42:30 | |

It was wonderful to see how the relationship | 0:42:37 | 0:42:39 | |

between the indri and the local people living alongside them | 0:42:39 | 0:42:43 | |

has changed so much. | 0:42:43 | 0:42:46 | |

But then, our attitudes have changed too. | 0:42:46 | 0:42:49 | |

When I came here 50 years ago, I was asked to collect some animals alive | 0:42:49 | 0:42:53 | |

and bring them back to Britain. | 0:42:53 | 0:42:55 | |

That was how zoos operated in those days, | 0:42:55 | 0:42:58 | |

believing, misguidedly, that when one of their exhibits died, | 0:42:58 | 0:43:03 | |

you could always go out and catch more to replace it. | 0:43:03 | 0:43:06 | |

And I did my best to assemble a few animals I thought might make interesting displays. | 0:43:06 | 0:43:11 | |

The Zoo Quest series started as a collaboration with the London Zoo, | 0:43:25 | 0:43:30 | |

so I found myself as an animal-catcher as well as everything else. | 0:43:30 | 0:43:35 | |

One centetes, one coracopsis, one roller. | 0:43:35 | 0:43:41 | |

24 foly, those are like sparrows. | 0:43:41 | 0:43:43 | |

Ten chameleons, six assorted lizards, three boas, a hundred myriapods! | 0:43:43 | 0:43:49 | |

Bonkers. And I had to feed all these damn things. | 0:43:51 | 0:43:55 | |

Funny way to make television programmes, I can tell you. | 0:43:55 | 0:44:00 | |

And I have collected some beautiful myriapods... What did I say there? | 0:44:00 | 0:44:05 | |

I think a hundred or something. | 0:44:05 | 0:44:06 | |

They were lovely millipedes | 0:44:06 | 0:44:08 | |

the size of golf balls when they were rolled up | 0:44:08 | 0:44:11 | |

and when they weren't, they would run around like little trains, | 0:44:11 | 0:44:15 | |

red with black stripes on them. | 0:44:15 | 0:44:17 | |

And they got out in the middle of the night in the hotel | 0:44:17 | 0:44:21 | |

and they were all over the corridor and all of the rooms and madame was not pleased, not at all pleased. | 0:44:21 | 0:44:28 | |

In rainforests like this, you come across all kinds of unexpected delights. | 0:44:34 | 0:44:40 | |

This rather large snake... | 0:44:46 | 0:44:47 | |

..is quite harmless, in fact, | 0:44:50 | 0:44:52 | |

but it's quite mysterious too, | 0:44:52 | 0:44:57 | |

because that, | 0:44:57 | 0:44:59 | |

you would think in Africa, was a python, | 0:44:59 | 0:45:02 | |

and Africa is just over the way. | 0:45:02 | 0:45:04 | |

But in fact, it's a boa constrictor | 0:45:06 | 0:45:08 | |

and its nearest relatives | 0:45:08 | 0:45:11 | |

are right on the other side, in South America. | 0:45:11 | 0:45:15 | |

It's one of the mysteries of Madagascar's fauna. | 0:45:15 | 0:45:20 | |

The last time I was here, there was a belief | 0:45:21 | 0:45:25 | |

that animals like this, this boa, | 0:45:25 | 0:45:27 | |

were the incarnations of people's grandmothers. | 0:45:27 | 0:45:32 | |

I did have some inhibitions | 0:45:32 | 0:45:35 | |

about what people would think if I caught one of those | 0:45:35 | 0:45:38 | |

and took away their grandmother, so I never did. | 0:45:38 | 0:45:41 | |

This beautiful lemur has now become a symbol | 0:46:08 | 0:46:12 | |

of the fight to conserve the forest | 0:46:12 | 0:46:14 | |

and save it from the fate | 0:46:14 | 0:46:15 | |

that overtook so many of Madagascar's animals in the recent past. | 0:46:15 | 0:46:21 | |

So, why did the elephant bird disappear? | 0:46:27 | 0:46:30 | |

It could have been climate change which turned much of its land into desert. | 0:46:30 | 0:46:36 | |

It could have been that people destroyed the forests where it browsed. | 0:46:36 | 0:46:40 | |

I doubt if it was hunted to extinction. | 0:46:40 | 0:46:43 | |

Anyone who's seen an ostrich in a zoo | 0:46:43 | 0:46:46 | |

knows it's got a kick that can open a man's stomach, | 0:46:46 | 0:46:49 | |

and an enraged elephant bird many times the size of an ostrich | 0:46:49 | 0:46:53 | |

must have been a truly formidable opponent. | 0:46:53 | 0:46:56 | |

I suspect it was these. | 0:46:56 | 0:46:59 | |

His egg. | 0:46:59 | 0:47:01 | |

They may not have been able to tackle an adult bird | 0:47:01 | 0:47:04 | |

but they could take its eggs, which were a huge source of nourishment. | 0:47:04 | 0:47:10 | |

And so I think it's probably these | 0:47:10 | 0:47:12 | |

are the reason why the elephant bird is no longer here. | 0:47:12 | 0:47:16 | |

Even if the bird itself was held in awe, or maybe fear, by the people here, | 0:47:20 | 0:47:25 | |

they might not have had too much trouble in robbing it of its huge, nutritious eggs. | 0:47:25 | 0:47:30 | |

So, although there were several factors threatening the bird's survival, | 0:47:30 | 0:47:34 | |

it could have been people eating the eggs who dealt the species its final blow. | 0:47:34 | 0:47:40 | |

Today we've come to realise that if you want to preserve a species, | 0:47:48 | 0:47:53 | |

you have to preserve the whole community of plants and animals. | 0:47:53 | 0:47:57 | |

Some people here are trying to tackle that problem. | 0:47:57 | 0:48:02 | |

Ryan manages one such group in indri country. | 0:48:06 | 0:48:10 | |

I asked him how much forest remained. | 0:48:10 | 0:48:14 | |

As we speak, it's very fragmented. | 0:48:14 | 0:48:17 | |

Unfortunately in this particular area, we have almost no continuous forest any more. | 0:48:17 | 0:48:23 | |

This is a fragment of about 800 hectares. | 0:48:23 | 0:48:27 | |

One crucial issue for conservation | 0:48:27 | 0:48:30 | |

is to link these fragments with each other | 0:48:30 | 0:48:33 | |

so that there could be genetic exchange | 0:48:33 | 0:48:36 | |

between plant and animal species that life there. | 0:48:36 | 0:48:40 | |

So if they remained as fragments, really the inhabitants, the animal habitants, are doomed? | 0:48:40 | 0:48:46 | |

Yes, that's pretty much the case, and there are studies concerning the indri, for instance, | 0:48:46 | 0:48:52 | |

saying that a minimum size for a forest | 0:48:52 | 0:48:58 | |

in which the indri can survive is about 1,000, 2,200 hectares. | 0:48:58 | 0:49:04 | |

-You have to link them up. -Exactly. -And how are you doing it? | 0:49:04 | 0:49:07 | |

One thing that we try to do is actually re-establish the rainforest in-between these fragments | 0:49:07 | 0:49:14 | |

by planting trees | 0:49:14 | 0:49:16 | |

that we actually raise in this nursery here from the seeds that we collect in the forest. | 0:49:16 | 0:49:23 | |

And how's it going? How many are you replanting? | 0:49:25 | 0:49:28 | |

Well, we now have replanted an area of about 1,000 hectares. | 0:49:28 | 0:49:34 | |

We ideally have at least 60 species per hectare that you plant, | 0:49:34 | 0:49:39 | |

so this is kind of hard work. | 0:49:39 | 0:49:42 | |

How many trees to do you think you have planted? | 0:49:42 | 0:49:45 | |

If you take 1,000 trees per hectare as a rule of thumb | 0:49:45 | 0:49:50 | |

then this makes slightly more than a million trees now. | 0:49:50 | 0:49:53 | |

-A million trees in how many years? -That's in three years of planting. | 0:49:53 | 0:49:58 | |

Fantastic. A million in three years. | 0:49:58 | 0:50:01 | |

That is a lot of trees. | 0:50:01 | 0:50:03 | |

This is just so heartening and exciting. | 0:50:11 | 0:50:14 | |

How long do you think you're going to be before you can complete these corridors? | 0:50:14 | 0:50:18 | |

Well, I would say that probably you would need 20 years or so | 0:50:18 | 0:50:24 | |

to be sure that the trees replanted | 0:50:24 | 0:50:26 | |

have actually re-grown to something that you would call a forest. | 0:50:26 | 0:50:30 | |

So, we would actually look at all these reforested areas | 0:50:30 | 0:50:34 | |

for the next two decades to come. | 0:50:34 | 0:50:38 | |

Projects like this are wonderfully encouraging. | 0:50:38 | 0:50:42 | |

When I was here 50 years ago, we had no idea how complex | 0:50:42 | 0:50:47 | |

forest systems were like this | 0:50:47 | 0:50:49 | |

and how difficult they would be to reconstitute. | 0:50:49 | 0:50:52 | |

But plans like that can only work if they have the support of the local people. | 0:50:52 | 0:50:58 | |

South of Tana, in the central highlands, | 0:51:05 | 0:51:08 | |

there's a new initiative which is an inspiring example | 0:51:08 | 0:51:12 | |

of how a local community project could help the future of the country's wildlife. | 0:51:12 | 0:51:16 | |

The coordinator of this project, Eugenie, | 0:51:16 | 0:51:21 | |

told me that the people here have very little to live on | 0:51:21 | 0:51:25 | |

and that they need their local forest to survive. | 0:51:25 | 0:51:28 | |

So, in order to provide work for local people which doesn't destroy the forest, | 0:51:57 | 0:52:02 | |

Eugenie has helped set up a scheme to produce silk | 0:52:02 | 0:52:05 | |

which, by tradition, the Malagasy use to weave a magnificent fabric. | 0:52:05 | 0:52:10 | |

First of all, the caterpillars of a particular moth are released into the forest. | 0:52:12 | 0:52:17 | |

When they change into cocoons, they are collected. | 0:52:22 | 0:52:27 | |

Then the silk is unwound from the cocoon | 0:52:34 | 0:52:37 | |

and spun into a thread which is dyed and ultimately woven. | 0:52:37 | 0:52:42 | |

The scheme has created work for all the women in the village, including Marie. | 0:52:44 | 0:52:50 | |

This project has completely changed people's attitude to their forest. | 0:53:18 | 0:53:22 | |

The villagers now have an incentive to protect the trees | 0:53:22 | 0:53:27 | |

which provide them with such a valuable income | 0:53:27 | 0:53:30 | |

and that, of course, in turn protects the wildlife. | 0:53:30 | 0:53:32 | |

Initiatives like this silk project | 0:53:35 | 0:53:37 | |

bring hope for the future of Madagascar. | 0:53:37 | 0:53:40 | |

For a young man, the Zoo Quest trip was an exciting adventure | 0:53:41 | 0:53:45 | |

to what was then, in television terms at least, an unexplored land. | 0:53:45 | 0:53:50 | |

Coming back after 50 years has been really fascinating. | 0:53:50 | 0:53:54 | |

This time, I won't be returning home with a collection of animals for the London Zoo | 0:53:54 | 0:53:59 | |

but I will be coming back with a greater understanding of how and why Madagascar has changed. | 0:53:59 | 0:54:04 | |

I've seen a country which has been heavily exploited | 0:54:04 | 0:54:08 | |

but I've also seen glimmers of hope for the future of the wildlife here | 0:54:08 | 0:54:12 | |

and I've been thrilled to get so close to some of Madagascar's most wonderful species, | 0:54:12 | 0:54:18 | |

a reminder of just how special this island is. | 0:54:18 | 0:54:21 | |

50 years ago, I found the egg of what is surely among | 0:54:27 | 0:54:31 | |

the most spectacular of all the animals to evolve here. | 0:54:31 | 0:54:34 | |

Now there is still one final detail to fill in. | 0:54:34 | 0:54:38 | |

How old is my egg and what might that tell us? | 0:54:38 | 0:54:41 | |

Here in the archaeological department at Oxford University | 0:54:46 | 0:54:49 | |

there's a carbon-dating apparatus | 0:54:49 | 0:54:52 | |

which can accurately find the age of ancient objects, natural and man-made. | 0:54:52 | 0:54:58 | |

It's a complicated process involving kinds of very sophisticated techniques | 0:54:58 | 0:55:04 | |

but I've been told that Thomas Higham, who took the sample from my egg, has got a result. | 0:55:04 | 0:55:10 | |

You took a tiny bit of this, I know... | 0:55:12 | 0:55:15 | |

-A very small amount from the back. -A very small amount. | 0:55:15 | 0:55:18 | |

And tell me, come on, what's the answer? | 0:55:18 | 0:55:20 | |

Well, our dates suggest that this egg is 1,300 years old. | 0:55:20 | 0:55:24 | |

-No! -Yes. | 0:55:24 | 0:55:27 | |

-Say it again. One thousand... -1,300 years old. -And that puts it at what date? | 0:55:27 | 0:55:32 | |

About 700... 600 to 700 AD. | 0:55:32 | 0:55:34 | |

And did that surprise you? | 0:55:34 | 0:55:36 | |

-It was quite a lot younger than I thought it would be, actually. -You thought it could be older? | 0:55:36 | 0:55:42 | |

I did, and I say that because I checked back | 0:55:42 | 0:55:45 | |

on the other eggshell dates that we've dated from Madagascar, | 0:55:45 | 0:55:49 | |

and the youngest date that we've ever got is about 900 AD. | 0:55:49 | 0:55:54 | |

Here is 600 AD, 800 AD, | 0:55:54 | 0:55:57 | |

and your dates are these ones that just sit in here, | 0:55:57 | 0:56:00 | |

and these are the youngest ones. | 0:56:00 | 0:56:01 | |

-So, it's quite a recent one in terms of... -It is. Indeed. | 0:56:01 | 0:56:05 | |

So this, in fact, was one of the last of the elephant birds. | 0:56:05 | 0:56:11 | |

I think within 100 to 200 years, perhaps. | 0:56:11 | 0:56:15 | |

-Perhaps, yes. -Ah. | 0:56:15 | 0:56:17 | |

The chick that came out of this was one of the last. | 0:56:17 | 0:56:22 | |

-Absolutely amazing. -When do you think it disappeared? | 0:56:22 | 0:56:25 | |

I think somewhere before 1000 AD it was extinct, largely extinct, yeah. | 0:56:25 | 0:56:30 | |

So, there we have it. | 0:56:34 | 0:56:36 | |

My egg is 1,300 years old | 0:56:36 | 0:56:38 | |

and one of the most recent eggs of its kind | 0:56:38 | 0:56:41 | |

that the university has dated. | 0:56:41 | 0:56:43 | |

But that doesn't mean that it was the last ever laid, | 0:56:43 | 0:56:46 | |

and it could be that some of these astounding creatures lived on until much more recently. | 0:56:46 | 0:56:51 | |

But what we have discovered is that elephant birds and human beings | 0:56:51 | 0:56:56 | |

did manage to live alongside one another for hundreds of years. | 0:56:56 | 0:57:00 | |

So, it wasn't the usual story of finding a new species | 0:57:00 | 0:57:03 | |

and then exterminating it within a few decades of finding it, | 0:57:03 | 0:57:07 | |

as happened with the dodo in Mauritius, a much smaller island not far away from Madagascar. | 0:57:07 | 0:57:13 | |

Nonetheless, the elephant bird did ultimately disappear. | 0:57:13 | 0:57:17 | |

Another example of how human beings, in their ever-increasing numbers, | 0:57:17 | 0:57:22 | |

can so easily have a lethal effect on the animals around them. | 0:57:22 | 0:57:25 | |

For me, this egg is a reminder of how easy it is | 0:57:29 | 0:57:33 | |

for species to disappear and be exterminated | 0:57:33 | 0:57:37 | |

as human beings take over more and more of the natural world. | 0:57:37 | 0:57:42 | |

But there is hope. | 0:57:42 | 0:57:44 | |

We understand more about ecology and ecosystems, | 0:57:44 | 0:57:48 | |

more about what needs to be done to protect the natural world. | 0:57:48 | 0:57:52 | |

And I hope, certainly, that we take those lessons to heart in Madagascar | 0:57:52 | 0:57:58 | |

to safe its wonderful wildlife, | 0:57:58 | 0:58:01 | |

for it is indeed an island of marvels. | 0:58:01 | 0:58:05 | |

Subtitles by Red Bee Media Ltd | 0:58:39 | 0:58:42 |